FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Jump to details:

Critic Grant H. Palmer stated the following about the Book of Abraham in his 2002 book Insider’s View of Mormon Origins:

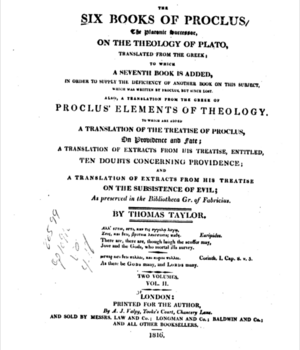

The astronomical phrases and concepts in the Abraham texts were also common in Joseph Smith’s environment . For example, in 1816 Thomas Taylor published a two-volume work called The Six Books of Proclus on the Theology of Plato. Volume 2 (pp. 140-146) contains phrases and ideas similar to the astronomical concepts in Abraham 3 and Facsimile No. 2. In these six pages, Taylor calls the planets “governors” and uses the terms “fixed stars and planets” and “grand key.” Both works refer to the sun as a planet receiving its light and power from a higher sphere rather than generating its own light through hydrogen-helium fusion (cf. Fac. 2, fig. 5).[see footnote][1]

Palmer alleges that there are several similarities between the The Six Books of Proclus and the Book of Abraham. These include:

This article will seek to refute Palmer’s criticism.

This article will approach response by doing one or more of the following five things for each piece of evidence that supposedly supports this criticism.

References to the The Six Books of Proclus are quoted using an online copy of the book found here.

There is no known historical evidence that places Joseph Smith or one of his associates in contact with this work by the time of the translation of the Book of Abraham. If one wishes to see the evidence for which works Joseph Smith did have contact with, references can be found in the citation below.[2]

Uses in the Book. Palmer's reference comes from Book 2, page 140. The quotation relevant to Palmer's claim reads:

But the planets are called the Governers of the world...and are allotted a total power.

Uses in the Book of Abraham. The Book of Abraham does not use the word "governor" ever. When derivative words like "govern" and "governing" are used, they are used mostly in reference to Kolob, a star and not a planet. The exception is Facsimile 2 Figure 2 in which the figure is said to "[stand] next to Kolob, called by the Egyptians Oliblish, which is the next grand governing creation near to the celestial or the place where God resides; holding the key of power also, pertaining to other planets; as revealed from God to Abraham, as he offered sacrifice upon an altar, which he had built unto the Lord." There is one instance in which a “planet” (more particularly, the sun) is said to rule over the day on earth and another (the moon) is said to rule over the night.[3]

In the Ancient World. The reference to stars and/or planets as governing or ruling bodies is hardly out of line with the ancient world. There is a publication whose original creation has been dated close to the dating of the Joseph Smith Papyri and whose first translation into English occurred after Joseph Smith's death, The Apocalypse of Abraham. It states that “the host [of divine beings] I [Abraham] saw on the seventh firmament commanded the sixth firmament and it removed itself. I saw there on the fifth (firmament), hosts of stars, and the orders they were commanded to carry out [by the beings on the sixth and seventh firmaments], and the elements of the earth [below them] obeying them” (19:8-9).[4] There are other texts from the ancient world that resemble this idea.[5] The biblical creation accounts themselves reflect this idea with things like Genesis 1:16–18 which reads:

We see here that a star (the sun) and a planetary body (the moon) are said to rule over the day and night upon the earth. Clearly, this is not a concept exclusive to The Six Books of Proclus. "Stars" and "planets" seem to be interchangeable terms in the ancient world that can refer to nearly any astronomical body.

One critic has stated that both Thomas Taylor and Joseph Smith "utilize the number fifteen when referring to planets within [their] governing system."[6]

Uses in the Book. The reference made by the critic in the book is from Book 7, page 146 of The Six Books of Proclus. There we read:

According to the Chaldaic dogmas, as explained by Psellus, there are seven corporeal worlds, one empyrean and the first; after this three etherial; and then three material worlds, viz. the inerratic sphere, the seven planetary spheres, and the sublunary region. They also assert that there are two solar worlds.

The critic asserts that this makes "fifteen planets in all."

The claim is utter nonsense on the part of the critic when examining the source closely. Following the logic of the source, there are seven worlds. The first is "empyrean" which refers to the "highest heaven, where the pure element of fire has been supposed to subsist."[7] Then there is a division between six of these seven worlds into two groups: "etherial" and "material." Under the material ("viz.") world there is the inerratic sphere, the seven planetary spheres, and the sublunary region. Thus in these worlds, there are "regions" aka "spheres" that may have planets but we are still speaking about seven worlds. Then, finally, there are two other solar worlds besides these first seven. Thus we get nine worlds in total. It is evident that the critic has severely misunderstood his source.

Uses in the Book of Abraham. The Book of Abraham speaks of "[k]ae-e-vanrash, which is the grand Key [sic], or, in other words, the governing power, which governs fifteen other fixed planets or stars[.]" It is interesting to note that the Book of Abraham actually uses “kae-e-vanrash” as if part of a group of stars or planets. It is said to govern “fifteen other fixed planets or stars.” Thus there are sixteen bodies mentioned here. Again, this shows how badly the critic has understood his sources.

In the Ancient World. There is actually some evidence of special significance being attached to the number 15 in the ancient Egyptian world.

Hugh Nibley and Michael Rhodes, in their discussion of this very statement from this figure in Facsimile 2, write the following:

In his discussion of the Book of the Cow in the royal tombs, Charles Maystre pays special attention to the Tutankhamun version, the most carefully executed of the Heavenly Cow pictures (see p. 324, fig. 38): “Along the belly of the cow are stars.” [8] These are set in a line; at the front end is the familiar solar-bark bearing the symbol of Shemsu, the following or entourage, and at the rear end of the line is another ship bearing the same emblem. Both boats are sailing in the same direction through the heavens. The number of stars varies among the cows; in the instructions contained in the tomb of Seti I, it is specified that there should be nine, though the three groups of three strokes each can, and often do, signify an innumerable host.[9]

The number here plainly belongs to the cow, but what about the fifteen stars? “The number fifteen cannot be derived from any holy number of the Egyptians,” writes Hermann Kees, and yet it presents “a surprising analogy” with the fifteen false doors in the great wall of the Djoser complex at Saqqara, which was designed by the great Imhotep himself, with the Festival of the Heavens of Heliopolis in mind, following the older pattern of the White Wall of the Thinite palace of Memphis.[10] Strangely enough this number fifteen keeps turning up all along, and nobody knows why, though it always represents passing from one gate or door to another. Long after Djoser, Amenophis III built a wall for his royal circumambulation at the sed-festival, marking the inauguration of a new age of the world; it also had fifteen gates.[11] In the funeral papyrus of Amonemsaf, in a scene in which the hawk comes from the starry heavens to minister to the mummy, “the illustration . . . is separated into two halves by the sign of the sky ” —the heaven above and the tomb below (fig. 31). Between the mummy and the depths and the hawk in the heaven, there are twelve red dots and fifteen stars.[12] Again, twelve is the best-known astral number, but why fifteen? One Egyptologist wrote years ago that “[t]he author’s impression is that these [the fifteen stars] are purely theological features without astronomical significance.” [13] “The ‘great Ennead which resides in Karnak’ swelled to fifteen members.” [14] It was structured in three phases: one became two, two became four, four became eight, which is fifteen altogether. Étienne Drioton associates this with the dividing of eternity in the drama of Edfu into years, years into months, and months into fifteen units, these units into hours, and they into minutes.[15] Furthermore the idea of fifteen mediums or conveyors may be represented on the fifteen limestone tablets of the Book of the Underworld found by Theodore Davies and Howard Carter in the tomb of Hatshepsut.[16] Let us recall that the basic idea, as Joseph Smith explains it, is that “fifteen other fixed planets or stars” act as a medium for conveying “the governing power.” Coming down to a later time of the Egyptian gnostics, we find the fifteen helpers (παραστάται, parastatai) of the seven virgins of light in the Coptic Pistis Sophia, who “expanded themselves in the regions of the twelve saviors and the rest of the angels of the midst; each according to its glory will rule with me in an inheritance of light.” [17] In an equally interesting Coptic text, 2 Jeu, there are also fifteen parastatai who serve with “the seven virgins of the light” who are with the “father of all fatherhoods, . . . in the Treasury of the Light.” [18]. They are the light virgins who are “in the middle or the midst (μέσος, mesos),” meaning that they are go-betweens.[19] Parastatai are those who conduct one through a series of ordinances, just as the fifteen stars receive and convey light.In all this we never get away from cosmology and astronomy. In the Old Slavonic Secrets of Enoch, “four great stars, each having one thousand stars under it,” go with “fifteen myriads of angels,” [20] all moving, to quote Joseph Smith, together with “the Moon, the Earth, and the Sun in their annual revolutions.” In the Book of Gates, one of those mystery texts reserved for the most secret rites of the greatest kings, we see, as Gustave Jéquier describes it, “a long horizontal bar with a bull’s head at either end, supported by eight mummiform personages, and carrying seven other genies” (fig. 32).[21]These fifteen figures are designated as carriers or bearers (f.w), and the bar is the body of the bull extended to give them all room. A rope enters the bull’s mouth at one end and exits at the other, and on the end of this rope there is a sun-bark being towed by a total of eight personages designated as stars.[22] Just as the ship travels through the fifteen conveyor stars on the underside of the cow, the two heads of the bull make him interchangeable with the two-headed lion Aker, or Ruty, who guards the gate. “Aker,” writes Jéquier, “is a personification of the gates of the earth by which the sun must pass in the evening and in the morning.” [23] He is the same as the two-headed Janus, the gate-god, whom we have already met.[24]

Uses in the Book. There seems to be six references to “fixed stars” in The Six Books of Proclus. Five of these are found in book 2 page 139 and book 7 pages 93, 140, 141, and 216. The sixth reference comes from the table of contents in which, under the heading for chapter 14 of Book 7, it reads:

The peculiarities of the celestial Gods separately discussed.—Why the one sphere of the fixed stars comprehends a multitude of stars, but each of the planetary spheres convolves only one star. –And that in each of the planetary spheres, there is a number of satellites, analogous to the choir of the fixed stars, subsisting with proper circulations of their own.

Uses in the Book of Abraham. The only use of something that is close to this phrase comes from Facsimile 2 Figure 5 in which the figure is designated (in part) "[k]ae-e-vanrash, which is the grand Key, or, in other words, the governing power, which governs fifteen other fixed planets or stars[.]" It is interesting to note that the phrase is changed to “fixed planets” instead of “fixed stars.” The Six Books of Proclus does not contain the phrase "fixed planets."

In the Ancient World. “Sumerian and Akkadian names of stars and constellations occur in cuneiform texts for over 2,000 years, from the third millennium BC down the death of cuneiform in the early first millennium AD, but no fully comprehensive list was ever compiled in antiquity. Lists of stars and constellations are available in both the lexical tradition AND ASTRONOMICAL-ASTROLOGICAL TRADITION OF THE cuneiform scribes. The longest list in the former is that in the series Urra=hubullu, in the latter those in Mul-Apin…The term star, per se, as it is most commonly used in English to refer to individual fixed stars, does not exist in either Sumerian or Akkadian. Instead, the nouns commonly translated as “star” in English, Sumerian mul = Akkadian kakkabu, refer to a full range of observed astronomical phenomena including the fixed stars but also constellations, planets, mirages, comets, shooting stars, etc…Thus, when speaking of Mesopotamian star lists [those which Abraham might be most familiar]. What is generally meant is a collection of names of constellations, with the occasional name of a fixed star or planet included.”[25]

John Gee, William J. Hamblin, and Daniel C. Peterson:

In the Book of Abraham, there is a seeming confusion between the uses of the terms stars and planets. The key phrase in this regard is Abraham 3:13, which discusses the “stars, or all the great lights, which were in the firmament of heaven.” This verse is essentially a catalog of celestial bodies…What is conspicuously absent from this catalog are the planets. However, as we interpret it, the phrase “all the great lights. . . of heaven,” should be understood to include both the stars and the planets. This is consistent with most ancient systems of astronomy, where the planets were seen as planetes asteres or “wandering stars.”[26] According to Dicks, in Greek ‘astron is a general word (as indeed is aster) which can be applied indifferently to the fixed stars, the planets, the sun, and the moon.”[27] Likewise, in ancient systems of astronomy, the planets are consistently viewed as special types of stars but stars nonetheless. For example, Venus was called sb3 d 3, the “crossing star”; Jupiter was the sb3 rsy (n) pt, “southern star of the sky”; and Saturn was called sb3 i3bty d3 pt,” the eastern star which crosses the sky.”[28] The Babylonians also refer to planets as a special category of star.[29] In general, the planets are kakkab samas: the “Star of the sun.”[30] Likewise, Mercury and Mars are also called stars.[31] Thus, the Book of Abraham’s seeming “confusion” of planets and stars is in fact perfectly acceptable when viewed from an ancient perspective.[32]

Uses in the Book. There is one use of the phrase “grand key” in The Six Books of Proclus. It comes from Book 2, page 142. In a footnote to the page, we read:

This theory to is one of the grand keys to the theology of the Greeks.

The "theory" appears to be, upon reading from Taylor, that the Gods are those that give orbital motion to planets and that they also give them some of their natural powers though the text from Taylor is quite esoteric and cryptic and thus not much can be ascertained by the author.

Uses in the Book of Abraham. The phrase “grand key” comes again from Facsimile 2 Figure 5 in which the figure is “called in Egyptian Enish-go-on-dosh; this is one of the governing planets also, and is said by the Egyptians to be the Sun, and to borrow its light from Kolob through the medium of Kae-e-vanrash, which is the grand Key, or, in other words, the governing power, which governs fifteen other fixed planets or stars, as also Floeese or the Moon, the Earth and the Sun in their annual revolutions.” The Book of Abraham, at seeming difference from Taylor, does not seem to tie the "grand key" to a theory nor a material God. The use in the Book of Abraham may be tied to a "power" or to a "planet" as the explanation refers to "fifteen other fixed planets or stars." Given the evidence of planets or stars acting as ruling forces in the ancient world (as discussed above), perhaps it is more likely that this is referring to a planet.

In the Ancient World. With present research, we can’t determine what exactly is meant by Joseph Smith with this explanation. It may have something to do with the Light of Christ. It may have to do with a star or planet as "governing" bodies (for which, see above). It may have something to do with what is referred to in Fac 2. Fig 2, with some similarity to this figure, as “the key of power.” Hugh Nibley, commenting on this claim, wrote:

Staff and Key Joseph Smith calls the staff a key, "the key of power". The Hebrew word for key [Hebrew script] (miptah), means literally "opener," while the Egyptian name of the god who bears this staff is Wp-w3.wt = Opener of the Ways. The Egyptian obsession with "the Way" as the course of life here and hereafter, eloquently expressed in the First Psalm and in the preaching of the great high priest Petosiris--"I will show you the Way of Life"--has been discussed at length by scholars such as Oswald Spengler and Gerturd Thausing.[33] Peter is one who has the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:19). Janus also is the god "who holds a staff in his left and a key in his right,"[34] "the one who holds the key (clavigerus),"[35] and the one who is "the gatekeeper of the heavenly courts (coelestins ianitor aulae)."[36] The Egyptian is constantly concerned with being checked or blocked (h.sf) in his career. Only real power, the power of the key, can overcome his determined opponents.[37]

If truly referring to a planet that acts as the governing power over fifteen other planets or stars, then there is also evidence to support this in antiquity which was previously discussed and may be found above.

Uses in the Book. It is difficult to understand what to look for in the book that would help us understand where Palmer is drawing information for this evidence from. With such ambiguity, readers are invited to search it for themselves.

Earlier Articulations of the Same Concept. As early as December 1832 to January 1833, Joseph Smith revealed that a special power known as the Light of Chist is “truth [which] shineth. This is the light of Christ. As also he is in the sun, and the light of the sun, and the power thereof by which it was made.“[38]

In the Ancient World. It is difficult to understand why Palmer would assume that an ancient document would reflect a modern, scientific view of the the sun's light instead of an ancient, more spiritual one. The concept of the sun receiving light from a higher sphere is, again, hardly out of line with the ancient understanding of the cosmos as expected of the Book of Abraham.

Commenting on Facsimile 2, Figures 22 and 23 of the Book of Abraham, Hugh Nibley and Michael Rhodes wrote:

Inseparable from our figure 1 are the reverential apes on either side of him—figures 22 and 23 (see appendix 2). On other hypocephali they are sometimes two in number, sometimes four, six, or eight; sometimes standing and sometimes seated. They are identified as stars. As early as the Pyramid Texts, they are designated as “the Beloved Sons” of Sothis/Sirius, the brightest star in the sky.[39] It is assumed that the position of the apes shows them warming their hands as they greet the rays of the rising sun after the cold desert night and seeming to shield their eyes from the glory of the sunrise. So they are stars receiving light from a greater star, as Joseph Smith’s explanation declares. There was nothing to indicate to Joseph Smith that they are stars, yet along with the Pyramid Texts we have a vignette in the 17th chapter of the Book of the Dead in which each of these apes is preceded by a star (fig. 22).[40]

Thus this criticism has no bearing on the authenticity of the Book of Abraham.

Uses in the Book. The relevant citation that Palmer uses to look for the plurality of Gods can be found on page xi of the introduction to the first book which reads:

Hence, says the elegant Maximus Tyrius, “you will see one according law and assertion in all the earth, that there is one God, the king and father of all things, and many Gods, sons of God, ruling together with him. This the Greek says, and the Barbarian says, the inhabitant of the Continent, and he who dwells near the sea, the wise, and the unwise. And if you proceed as far as to the utmost shores of the ocean, there also there are Gods, rising very near to some, and setting very near to others.” This dogma, too, is so far from being opposed by either the Old or New Testament, that it is admitted by both, though it forbids the religious veneration of the inferior deities, and enjoins the worship of one God alone, whose portion is Jacob, and Israel the line of his inheritance. The following testimonies will, I doubt not, convince the liberal reader of the truth of this assertion.

It is quite interesting that Palmer does not mention that the doctrine might be found in the Bible. That would be a much more likely source for this doctrine than an obscure book commenting on the theology of Plato. This is discussed more below.

In the Ancient World. Both the multiplicity of Gods and the council of Gods motif can be found in abundance in the ancient Mesopotamian world and assuredly in ancient Egypt.

Pearl of Great Price Central has written a fantastic essay that can be found by following the link to the side of this page. As they have written:

One thing that differentiates the Book of Abraham’s account of the Creation from the biblical account in Genesis is that the Book of Abraham mentions plural “Gods” as the agents carrying out the Creation...After the lifetime of Joseph Smith, archaeologists working in Egypt, Syria-Palestine, and Mesopotamia uncovered scores of texts written on papyrus, stone, and clay tablets...One way in which these creation myths were different from the Creation account in Genesis was the clear, stark portrayal of what came to be widely called the divine or heavenly council...Over time a general consensus has been reached that the Bible does indeed portray a multiplicity of gods, even if there remains individual scholarly disagreement over some of the finer details.

Uses in the Book. The relevant passage that Palmer refers to in the book states:

The first [demiurgic] God, therefore, produces from and through himself the divine genera of the universe, according to his beneficent well. But he governs mortal natures through the junior Gods, generating indeed these also from himself, but other Gods producing them as it were with their own hands. For he says, “these being generated through me will become equal to the Gods.”

Earlier Articulations of the Same Concept. Joseph Smith had already revealed several texts that showed man’s ability to become like God. For instance, the Book of Mormon contains a few references that implicitly affirm man’s ability to become like God.[41] The Doctrine & Covenants explicitly affirms the doctrine of deification as early as February 1832.[42]

In the Ancient World. There are better parallels than this that we can find in the ancient world. For example, a translation of the fourth column and 10th-13th lines of the Book of the Dead contained on Joseph Smith Papyi XI and X reads:

This translation demonstrates that the Book of the Dead was often conceived of as allowing the deceased to become like God.

Michael Rhodes wrote the following commenting on Figures 8-11 of Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham:

Joseph Smith explained that the remaining figures contained writings that cannot be revealed to the world. Stressing the secrecy of these things is entirely in harmony with Egyptian religious documents such as the hypocephalus and the 162nd chapter of the Book of the Dead. For example, we read in the 162nd chapter of the Book of the Dead, “This is a great and secret book. Do not allow anyone's eyes to see it!” Joseph also says line 8 “is to be had in the Holy Temple of God.” Line 8 reads, “Grant that the soul of the Osiris, Shishaq, may live (eternally).” Since the designated purpose of the hypocephalus was to make the deceased divine, it is not unreasonable to see here a reference to the sacred ordinances performed in our Latter-day temples. [Figures 8-11 should actually be read from Figure 11 to Figure 8. Altogether it reads, "(Fig.11) O God of the Sleeping Ones from the time of the creation. (Fig.10) O Mighty God, Lord of heaven and earth, (Fig.9) of the hereafter, and of his great waters, (Fig.8) may the soul of the Osiris Shishaq be granted life."[44]

Commenting on their own translation of Figures 19, 20, and 21 of Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham, Hugh Nibley and Michael Rhodes wrote:

The text found in figures 19-21 are as follows: (21) [Egyptian hieroglyphs] (20) [Egyptian hieroglyphs] (19) [Egyptian hieroglyphs] (21) iw wnn=k (20) m ntr pf (19) dd.wy. (21) You shall ever be (20) as that God, (19) the Busirian.[45]

This continues the overall theme of the hypocephalus, and indeed Egyptian funerary literature in general. The deceased is promised that he will be like Osiris--he will be resurrected and live eternally as a god.[46]

Hugh Nibley summarized the Book of the Dead as a form of Egyptian temple endowment. The Book of Dead is organized, according to Professor Nibley, as follows:

It can be clearly seen that becoming like God was part and parcel with the Egyptian conception of the afterlife.

Uses in the Book. The quotation referenced by Palmer reads: “Everything, therefore, which is bound is dissoluble; and this is also the case with the works of the father. For these are, all bodies, the composition of animals, and the number of participated souls. But intellects which ride as it were in souls as in a vehicle, cannot be called the works of the father; for they were not generated, but were unfolded into light in an unbegotten manner, as if fashioned within the adyta of his essence, and not proceeding out of them.”

Earlier Articulations of the Same Concept. The Book of Mormon (1830) revealed that, prior to coming to earth, human beings could have spirits.[48] The Book of Moses, translated between June 1830 and February 1831,[49] gave additional confirmation that spirits had an existence separate from their bodies prior to being born.[50] A revelation given to Joseph Smith in March 1833 states that “[m]an was also in the beginning with God. Intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made, neither indeed can be.”[51] Joseph would not have even been aware of the Egyptian papyri from which he claimed to translate the book until a little over two years after that revelation was given.

In the Ancient World. The ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians did believe that many were foreordained or pre-elected to be rulers or to accomplish other tasks. More information can be found by following the link to the right.

This admittedly does not contain evidence for the eternality of the soul. It does have strong, implicit evidence that personal pre-existence can be found among ancient religions–a concept which fits rather nicely with the general theology of the Book of Abraham. It should be stated that spiritual beings for Plato would have been immaterial essences rather than material ones as Joseph Smith taught in May 1843.[52] The Book of Abraham's conception of spirit is not Platonic (i.e. does not affirm the immateriality of the spirit) and thus fits Egyptian and Mesopotamian thought better.

There is other ancient lore about Abraham that speaks about his seeing pre-existent spirits. Following is a listing of the traditions along with a bullet point list of various lore that supports the tradition. Translations of these various texts are all reproduced in Traditions about the Early Life of Abraham from FARMS. Page numbers will be listed on the sides of the titles so readers may find the traditions and read them for themselves in that volume. Comparisons to traditions that Joseph Smith may or may not have been aware of will be placed in footnotes:

Each of the supposed parallels can be plausibly tied to the ancient world, there is no historical evidence that Joseph Smith saw this work, and, indeed, many of the concepts claimed as parallels have their true revealed origin from a few to several years before the translation of the relevant portions of the Book of Abraham. Since the ancient parallels are closer, materially speaking, to the claims made of the Book of Abraham (and of course, such is natural considering that the subject material and culture in which both books emerged couldn’t be more different) the author judges them superior than those claimed by Palmer—effectively countering this rather shallow argument against the Book of Abraham.

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now