Summary

Historian Rebecca J. Clark explores Utah women’s pivotal role in the suffrage movement, the impact of faith and polygamy on voting rights, and their lasting civic contributions. She highlights key figures like Emmeline B. Wells and emphasizes the importance of preserving women’s history.

This talk was given at the 2021 FAIR on August 5, 2021.

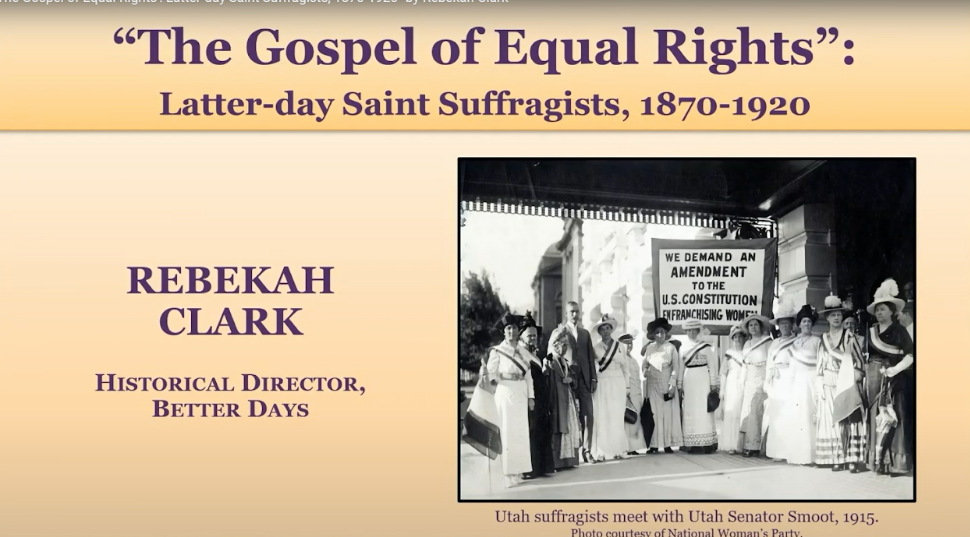

Rebekah Clark, historian for Better Days and co-author of Thinking Women: A Timeline of Suffrage in Utah, researches Utah women’s activism and national suffrage, bringing a deep understanding of faith-driven advocacy to her work.

Transcript

Rebekah Clark

Introduction

Thank you. It has been more than 20 years that as a freshman at Harvard, I took my seat in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s Women, Feminism, and History course, and I began to take notes as usual, not realizing how much that day would change my life. I had registered for the course not because I was a feminist, as I assured my family, but because Professor Ulrich was a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and more importantly for me, she was a Latter-day Saint woman.

Looking back, I was at a critical juncture. I was trying to fit into the mold of the expectations for a good Mormon girl, but I was also grappling with what does that really mean, and what I could or should be doing with the academic opportunity that I had been given. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was seeking examples of faithful women who had forged new paths to help me find my own.

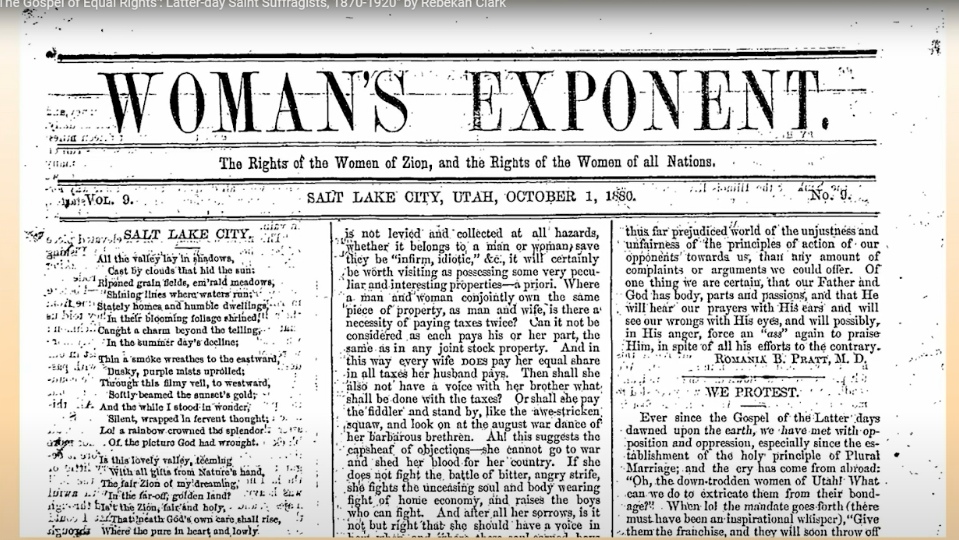

Woman’s Exponent

Now, in class that day, Professor Ulrich projected an image of the 19th-century Woman’s Exponent, which served as the Relief Society newspaper for 42 years and was also one of the longest-running pro-suffrage papers in the nation. She pointed to the masthead of this woman-run paper, the Rights of the Women of Zion and the Rights of the Women of All Nations. I learned that day, for the first time, that Latter-day Saint women had a long, rich, and very complex history at the very forefront of the early women’s rights movement.

The story of these early Relief Society suffragists spoke to me. It was a pivotal moment. I discovered models of empowered and deeply devout women whose advocacy for a more equal community didn’t conflict with, but was instead motivated by, their great faith in the restored gospel. But I was also hit with some troubling questions: Why haven’t I ever been taught this before? And then, what else haven’t I been told? In that moment, I knew that I was supposed to study these women more deeply and help share their stories so that others wouldn’t be left with those same questions.

My Passion

I became so inspired by this history that I actually switched my major. Ultimately, I wrote my Harvard honors thesis on Latter-day Saint women’s activism in the suffrage movement. I then participated in a postgraduate research fellowship on Latter-day Saint women.

Then began my journey into women’s history at BYU before then going on to law school, where I explored these concepts further through courses on election law, civil rights, and religious freedom. Even while practicing law, I never forgot that moment. It sparked a flame that ultimately changed my career trajectory to pursue history professionally.

Now I’ve been working as a historian and the historical director at Better Days for the past three and a half years to share the stories of the trailblazing women in Utah’s history.

Better Days

Better Days 2020, now known as Better Days, is an educational non-profit dedicated to amplifying women’s voices from the past and popularizing Utah women’s history. Our team has been motivated from the start by the belief that increasing public knowledge about women’s past efforts for equality has the capacity to strengthen future communities. This belief has propelled our efforts to incorporate more women’s history into classrooms and communities in a meaningful, representative, and diverse way.

Throughout the process, we have recognized that when our collective history is more inclusive and complete, it’s more powerful.

Our Book

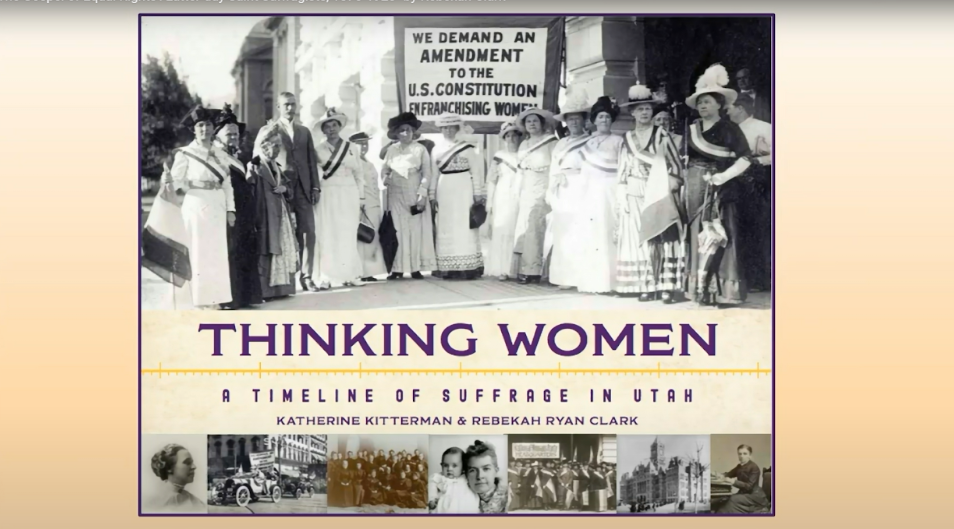

As part of that work this past year, Catherine Kitterman and I co-authored a book on Utah’s suffrage history called Thinking Women: A Timeline of Suffrage in Utah. This book, published by Deseret Book, seeks to capture the complexity and provide an in-depth but still accessible overview of the key events, the people, and the rich photographic imagery of more than five decades of Utah’s grassroots suffrage activism.

We drew our title from the words of Emmeline B. Wells, Utah’s preeminent suffragist, the fifth general Relief Society president, and the longtime editor of the Woman’s Exponent. I also named my youngest daughter after her because I love her so much. She once wrote, “I believe in women, especially thinking women.” We wanted to highlight the agency, individuality, and deliberate efforts of the thousands of Utah women on behalf of equality.

Latter-day Saint history is full of such thinking women who let their voices be heard to defend their faith and strive for the fulfillment of Joseph Smith’s prophetic vision of better days for women.

Women’s Stories

Women’s stories in general are often marginalized or omitted from textbooks. Compound that with the pervasive negative perceptions of Utah women and Latter-day Saint women that are as old as Utah territory, and it’s not surprising that over time, Latter-day Saint contributions to the Western, the national, and the international suffrage movement have largely slipped into obscurity.

In 1898, Martha Hughes Cannon stood before a congressional committee and boldly proclaimed, “The story of the struggle for women’s suffrage in Utah is the story of all efforts for the advancement and betterment of humanity.” It’s been humbling to be entrusted with telling these women’s stories, and I have sought and received many spiritual promptings along the way that have helped me shape and interpret this narrative.

I’d like to share with you today an overview of this remarkable history and some of the themes and insights that have emerged in the process of excavating and analyzing these stories.

Utah Women and the Right to Vote

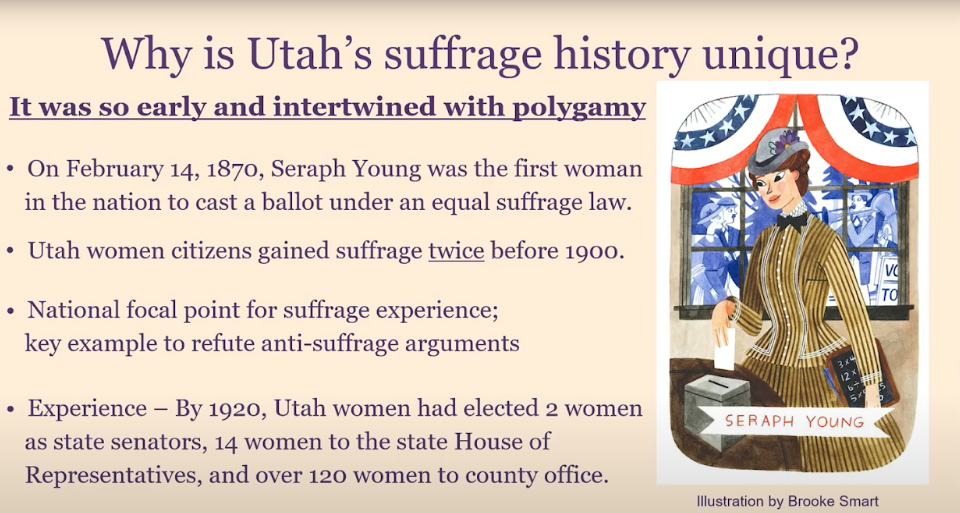

Utah women won the right to vote not once, but twice, long before many other American women were able to exercise any political rights. In 1870, a full 50 years before the passage of the 19th amendment, Latter-day Saint women made history as the first women in the nation to cast votes with equal suffrage rights open to all female citizens.

Now, to clarify before you all jump up in arms, Wyoming Territory granted women the right to vote first. Their legislature granted that right two months before Utah Territory. But Utah held its first local and general elections much earlier than Wyoming. So, Utah women hold the honor of being the first to actually cast their votes. Plus, the Utah women’s population was about 10 times as large as Wyoming at that point. So, it gave the nation the only really large, substantial population of voting women in the country that could sway elections.

After 17 years of actively voting, Utah women lost the right to vote when the national government disfranchised all Utah women in 1887. Most Utah women, particularly Latter-day Saint women, were outraged. They immediately mobilized and lobbied to regain their rights, which were restored in the new state constitution when Utah became a state in 1896.

Suffrage Engagement

After this victory, many Utah women remained actively engaged in the national suffrage movement up through the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920 and in the continuing efforts for greater political equality for all. Sharing their successes and their shortcomings in these efforts, provides instructive examples of women in leadership. It offers an intriguing counter perspective to persisting stereotypes and corrects lingering historical discrepancies.

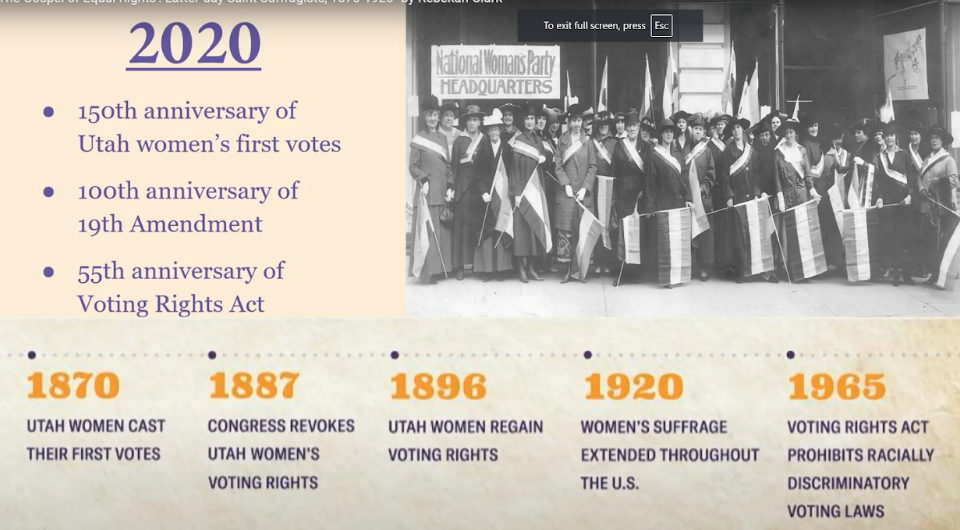

The year 2020, now notorious in so many ways, was really exciting for us leading up to it. It marked several key suffrage anniversaries that we worked really hard to commemorate, including the 100th anniversary, the centennial of the 19th amendment, the 150th anniversary of women’s first votes here in Utah, and the 55th anniversary of the landmark voting rights act that prohibited racially discriminatory laws.

Significantly, these suffrage anniversaries also converged with the 200th anniversary of the restoration of the Church through Joseph Smith. This is actually very appropriate because Latter-day Saint suffragists, in fact, saw their advocacy for women’s voting rights as part of the restoration of the gospel. I think that’s really important.

Women’s Relief Society

After the formation of the Women’s Relief Society in Nauvoo in 1842, the Prophet Joseph taught that the restoration of the Church of Christ was never perfect until the women were organized. He explained that he organized the Relief Society “according to the ancient priesthood,” and he declared that he turned the key to the women, promising them that “intelligence and knowledge shall flow down from this time. This is the beginning of better days for women.” Now, since that time, many Latter-day Saint leaders have actually attributed the true beginning of the modern women’s movement to the Relief Society’s formation and to Joseph’s prophetic declaration that day. It happened six years before the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls that we typically think of as the beginning of the modern movement.

Foundations of Suffrage

Sarah Kimball, who helped initiate the Relief Society in Nauvoo and then served for decades in Relief Society leadership in Utah, asserted that the sure foundations of the suffrage cause were deeply and permanently laid on the 17th of March 1842. That’s the Relief Society birthday. President George Albert Smith also, specifically, testified of this connection in 1945 saying, when the prophet Joseph Smith turned the key for the emancipation of womankind, it was turned for all the women of the world. From generation to generation, the number of women who can enjoy the blessings of religious liberty and civil liberty has been increasing.

Spiritual Significance of the Early Women’s Rights Movement

So, this brings me to my first theme: the deep spiritual significance found by many Latter-day Saints in the early movement for women’s rights. Doctrines of individual agency, female divinity, and eternal progression foster theological support for the principle of equal rights. In practical terms, the experiences of pioneering new settlements and practicing plural marriage further engendered women’s independence and interdependence, and their need to take on more public roles in a culture that was saturated with religiosity.

Evangelizing Suffrage Rhetoric

Latter-day Saints suffragists often evangelized their suffrage rhetoric. Consider, for example, this statement by Sanpete County’s suffrage association president in 1895, arguing for the continuation of suffrage associations even after they successfully regained their rights in the new state constitution. She declared, “We who have accepted the new gospel of equal rights must labor with untiring zeal for the redemption of the masses.” So, you hear that kind of missionary theme going through the way that they saw their work.

Their shared commitment to building the kingdom also motivated their political efforts. They sought to strengthen their community and defend their way of life as they followed President Eliza R. Snow’s counsel urging the sisters forward to be more useful and to take a wider sphere of action.

Latter-day Saints–Pioneers in Women’s Suffrage

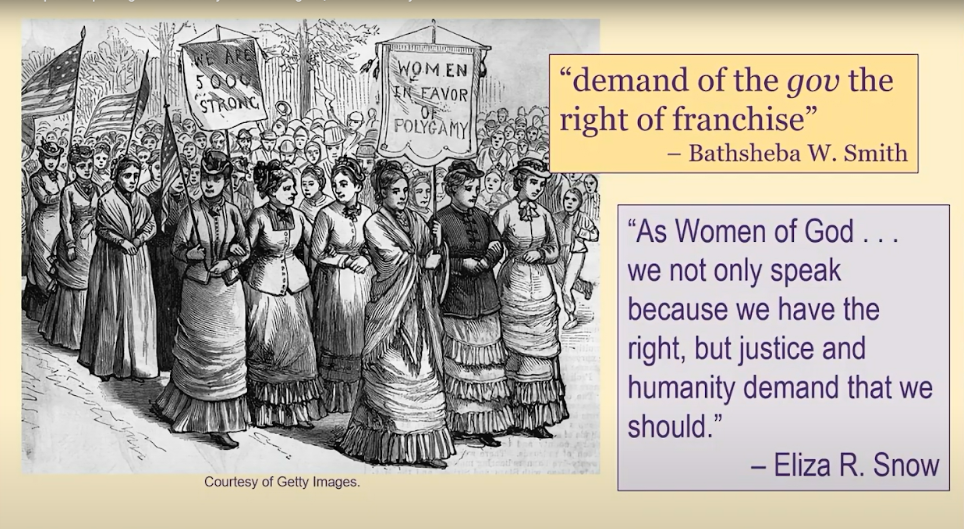

Latter-day Saints were pioneers in the movement for women’s suffrage, and they began their collective public activism in a dramatic fashion in January of 1870 at a large Relief Society meeting in the newly built 15th Ward Relief Society Hall. Future Relief Society General President Bathsheba W. Smith proposed that the women demand of the government to write a franchise so that they could more effectively defend their faith and their freedom of religion.

A ‘Great Indignation Meeting’

This is the first instance that we have on record of Latter-day Saint women publicly advocating for their own political rights. The next week, over 5,000 women gathered in the old tabernacle where the Assembly Hall now stands on Temple Square, and they held a great indignation meeting to protest against federal anti-polygamy legislation. They demonstrated that, contrary to the stereotypes at the time, Latter-day Saint women were, in fact, strong, articulate, decisive, independent, and fully committed to defending their religious beliefs.

A Legislative Victory

Their demonstration was effective. Just weeks later, in what was perhaps the easiest legislative victory of the entire suffrage movement, the Utah Territorial Legislature, composed entirely of Latter-day Saint men, unanimously granted women the right to vote in a Salt Lake City election. Two days later, on February 14, 1870, school teacher Sarah Young made history as the first woman in the nation to cast her vote under that equal suffrage law.

An Array of Emotions

Now, among Latter-day Saint women at the time, the reactions to this newly won right were positive but varied. Then mixed feelings among them demonstrated the inherent diversity of opinion that we see even within women’s experiences, even in this relatively homogeneous group like 19th-century Relief Society women. A week after Utah’s historic suffrage legislation was signed into law, a large group of Latter-day Saint women’s leaders met again at the 15th Ward Relief Society Hall, and Sarah Kimball boldly declared she could now openly declare herself a women’s rights woman.

I like that she couldn’t openly do it until it was official. The meeting minutes record that many of the women similarly now manifested their approval of women’s rights. Wilmar East announced, “I have never felt that women had her privileges. I always wanted a voice in the politics of the nation as well as to rear a family.”

Diversity of Opinion

But others were more cautious. Phoebe Woodruff was pleased with the reform and had looked to this day for years, but she warned that they should not run headlong and abuse the privilege. And Margaret T. Smoot admitted, “I have never had any desire for more rights than I have. I’ve always considered these things beneath the sphere of women. But as things progress,” she said, “I feel it’s right that we should vote.”

So, you see this kind of diversity of opinion I talked about. For the bolder advocates of women’s rights like Kimball, their already progressive beliefs uniquely aligned with their spiritual commitment to defend the Church through political activism. But for more reluctant women like Smoot, the sanction that they received from male and female leaders in the Church likely persuaded them of the acceptability and even the necessity of extending their sphere.

Responsibility

I appreciate this example of space for differences of opinion and their ability to still be able to join together in a common cause despite variation in their initial reactions and their motivations. These faithful women resolutely used their new political voice not only to defend their own rights and beliefs, but also to actively support the expansion of equal suffrage throughout the nation.

While Relief Society women quickly accepted this new responsibility and got to work teaching civics lessons and trying to become informed voters, the rest of the nation was still in shock. I love this quote from a leading newspaper at the time:

Utah is the land of marvels. She gives us first polygamy, which seems to be an outrage against women’s rights, and then offers the nation a female suffrage bill. Was there ever a greater anomaly known in the history of society?”

Many Americans felt just as baffled or outraged at the seeming disconnect of such a progressive stance coming from a community that practiced polygamy, which was popularly considered right along with slavery as one of the twin relics of barbarism.

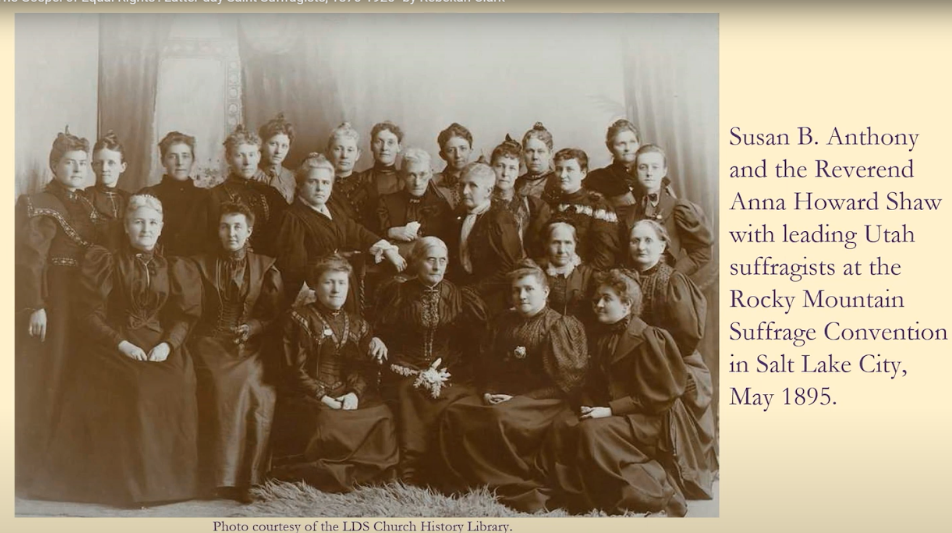

From the start, Latter-day Saints’ very involvement within the suffrage movement stirred nationwide controversy and debate about women’s rights, religious freedom, and citizenship. Utah’s suffrage experience was inextricably linked with the Saints’ controversial practice of polygamy. With its large and unique population of female voters, this remote western territory quickly emerged as a focal point of women’s suffrage in action. It drew high-profile suffrage leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Polygamy

National leaders had hoped that Utah’s women would use this newly gained political voice to overthrow the system of polygamy, but most Latter-day Saint women instead used their new rights and platform to defend their religion during the very height of the anti-polygamy movement.

The early political experience gained by Utah women as they voted, as they lobbied, even going to Washington, D.C. to lobby the President of the United States, and as they eventually held elected office here in Utah gave them unique opportunities to impact their communities and to refute anti-suffrage arguments. They demonstrated to the world that the world would not, in fact, fall apart if women were allowed to vote. But after 17 years, their rights were rescinded by Congress as part of the crippling anti-polygamy legislation that was designed to dismantle the Church’s political and economic power.

After Utah women were disenfranchised by that 1887 Edmunds Tucker law, they mobilized and formed a territorial branch of the National Suffrage Association along with a vast array of local and county associations in at least 21 counties in Utah. That’s what we’ve been able to find so far from the records, which are pretty vast. These suffrage organizations often mirrored the local Relief Society structure, and Relief Society presidents would at times simultaneously serve as the suffrage leaders for these organizations. Some local Relief Society minute books even contain entries with minutes from the suffrage meetings that would happen right after.

Uniquely High Community Support for Suffrage

This widespread activism contributed to another striking theme that we have found: the uniquely high level of community support for suffrage that was here in Utah, particularly among Latter-day Saints. This was not just a localized attempt by a few high-profile sisters in Salt Lake City; it was rather a widespread grassroots movement that involved thousands of rural women throughout the territory.

As one analysis shows, Utah had by far the highest rate of suffrage activity in the United States from the 1890s through the 1910s. So if you have any family members that lived in Utah during that time period, it is very likely that the women would have been suffragists.

It’s important to note here, though, that while Latter-day Saints constituted the vast majority of Utah’s population and Utah suffragists, they were not the only communities advocating for women’s political involvement. Suffrage support in the early years was largely divided along religious lines, with anti-polygamy leaders such as Jenny Freuseth and Cornelia Paddock even serving in national suffrage leadership and yet fighting against suffrage here in Utah in their own territory because they argued it was tainted by polygamy.

Women Uniting

But by the 1890s, as tensions over polygamy were beginning to subside and statehood was imminent, Latter-day Saint suffragists increasingly joined forces with women of other faiths to regain their rights through the new constitution.

We’ve also uncovered stories of women like Lizzie Taylor here, who helped run one of the newspapers for the small, but very politically active, black community in Salt Lake City in the 1890s. Lizzie organized political rallies, campaigned for candidates, spoke out against racial discrimination, encouraged voter registration among African-American women, and created organizations in which women of color could work together to improve their own communities. Newspapers at the time were supportive of such efforts, but the fact that these organizations were separated by race speaks to the marginalization that women of color were experiencing within the mainstream suffrage movement in Utah and also throughout the nation.

Support from Men

But Utah’s suffrage support also included widespread support from men, much more so than throughout the rest of the country. While suffragists in most other states had to overcome opposition from men in their own communities who were reluctant to relinquish any of their political power, Utah’s leading men were largely in favor of women’s equal right to vote. Women’s cooperation, rather than conflict with men, remained a hallmark of Latter-day Saint suffrage activism, and it contributed to their success here.

Such widespread support for women’s voting rights had complex and varied and nuanced motivations within the Latter-day Saint community. It included counteracting popular stereotypes of women as downtrodden, exploited victims, and provided additional electoral support against growing political opposition, especially after the completion of the transcontinental railroad. But there is also a large amount of clear evidence that many of the women themselves actively sought their own political voice and the expansion of their rights on the basis of equality.

I like to say that they were neither pawns nor militants here. Instead, Utah’s early endorsement of equal suffrage went beyond political expediency, and it indicated a trust in the joint partnership of men and women within the Church to improve society. As Apostle George C. Cannon urged,

With women to aid in the great cause of reform, what wonderful changes can be affected! But without her aid, how slow the progress. Give her responsibility, and she will prove that she is capable of great things, but deprive her of opportunities, make a doll of her, and leave her nothing to occupy her mind, and her influence is lost.”

Church Support

The official sanction of suffrage support from leaders of the Church was repeatedly communicated. Such as when the Relief Society General President Zina D. H. Young and Apostle Marion Lyman helped establish a local suffrage association in the Farmington ward in 1892. Elder Lyman assured the women that the First Presidency supported the suffrage cause and advised them to “take hold of this woman suffrage movement. Every Latter-day Saint woman should join and use her influence for good.”

This support became especially critical when the inclusion of women’s suffrage became the most hotly debated issue of the Constitutional Convention in the spring of 1895. Utah suffragists were highly organized at this point; they had secured pledges of support from almost every male delegate. But as the convention began, B. H. Roberts, one of the delegates, suddenly launched an eloquent attack against women’s suffrage and stoked fears that it would jeopardize statehood.

Whitney and Richards

Orson F. Whitney and Franklin S. Richards, both prominent members of the convention and the Church, boldly led the defense of women’s suffrage. Orson F. Whitney emphasized the spiritual basis for extending women’s rights, arguing,

It is women’s destiny to have a voice in the affairs of government. She was designed for it; she has a right to it. This great social upheaval, this woman’s movement, means something more than that certain women are ambitious to vote and hold office. I regard it as one of the great levers by which the Almighty is lifting up this fallen world.”

That was from Orson F. Whitney, and Franklin S. Richards cited equal suffrage as essential to the fuller measure of civil and religious liberty. Then he quipped, “I’ve never known a woman who felt complimented by the statement that she was too good to exercise the same rights and privileges as a man.”

Church Response

In response to these debates, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles met in the Salt Lake Temple and “unanimously condemned the stand taken against suffrage by B.H. Roberts.” First Counselor George C. Cannon recorded in his journal that the conversation brought several brethren to their feet in which they expressed themselves very strongly in favor of women’s suffrage, particularly Brother Joseph F. Smith, who spoke at many of the suffrage conferences.

President Smith was a great advocate for the women, and even really advocated for equal wages and other popular issues at the time that went beyond suffrage. Now, that same afternoon, a session of the general Relief Society Conference was gathered nearby in the assembly hall on Temple Square. Emmeline B. Wells, who was then serving as the general secretary of the Relief Society and was also the president of the Territorial Suffrage Association, spoke about the pending equal suffrage provision that was currently being debated. Then, Emily S. Richards made a motion for all the women to stand who favored equal suffrage in the Utah Constitution.

Constitutional Convention

The Woman’s Exponent records that, “Every woman in that large congregation was on her feet immediately.” So we see this widespread support, and because of that support and because of the dedicated lobbying by the Relief Society and the Utah Women Suffrage Association, the Constitutional Convention ultimately approved women’s suffrage by an overwhelming majority. The women’s right to vote, and now to hold office, was included in Utah’s new state constitution.

Susan B. Anthony came to Utah right after this victory at the constitutional convention to congratulate Utah women in person and to solicit their continued involvement in the national movement. At a large Rocky Mountain regional suffrage convention held in Salt Lake City in 1895, Utah suffragists welcomed suffrage leaders from surrounding states. They reaffirmed their commitment to the larger principle of political equality, and “they thought it the duty of all to work for the enfranchisement of women until universal suffrage should be obtained.”

Latter-day Saint Women Continue the Work of Suffrage Nationally

So this is perhaps my favorite part of the Utah suffrage story; the fact that the story did not end with statehood. After regaining their own voting rights, thousands of Latter-day Saints and other Utah suffragists remained genuinely committed to the national suffrage cause.

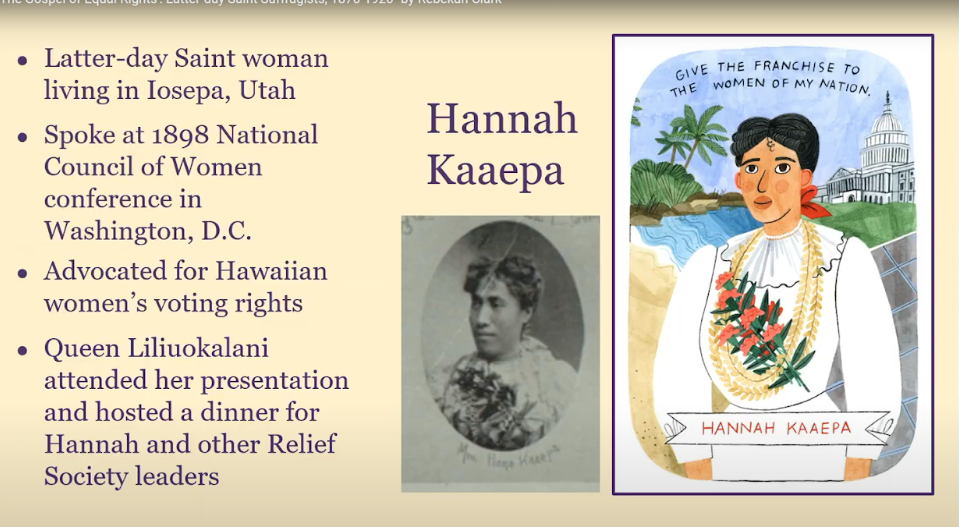

Suffrage advocacy gave Latter-day Saint women a national and even international platform to counteract negative stereotypes, to defend the Church, to improve their communities, and to contribute their unique perspective to leading women’s issues.

Church leaders repeatedly lent support and encouragement for women’s public advocacy, at times even funding trips to women’s rights conventions and setting apart the women attending those conventions as if they were going on missions.

I have loved learning about each of these women, and particularly, I love the example of Hannah Kaipa. She was a native Hawaiian Latter-day Saint who came to Utah and lived in the Iosepa community after the annexation of Hawaii. In 1898, she traveled with other Latter-day Saint delegates to Washington, D.C. She spoke at the third triennial National Council of Women conference, which had a broad reach to women’s organizations throughout the nation and had an international component that also met at the time. So she had a platform that was really unparalleled, and she presented Susan B. Anthony with a lei and publicly advocated for the voting rights of her own people, of Hawaiian women.

Women Running for Office

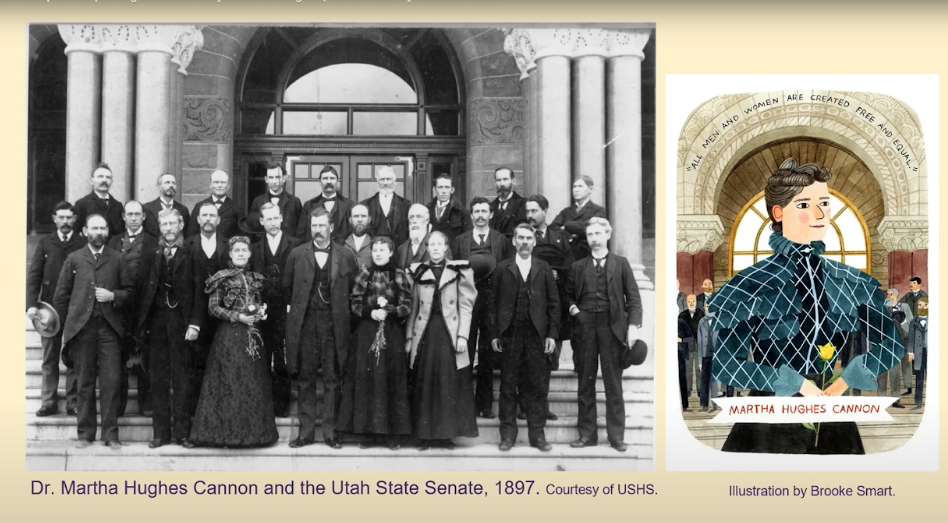

Another way that many Latter-day Saint women used their suffrage rights was by running for office at nearly every level and passing meaningful legislation for their communities. The most well-known of these early women legislators is Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the first woman in the nation elected as a state senator right here in Utah. During the 1896 election, the first election in which women could run for office here, Martha made headlines by running against and beating her own husband. Imagine that.

As a medical doctor and public health advocate who had earned four degrees by the time she was 25 years old, and this was at a time when few women even went to college, Martha revolutionized public health and sanitation in Utah. She actually advocated for vaccinations and quarantines during the smallpox epidemic. So I have this theory that I think she would have been really right at home here this past year.

And she also advocated for equality and argued no privileged class either of sex, wealth, or dissent should be allowed to arise or exist. All persons should have the same legal right to be the equal of every other if they can.

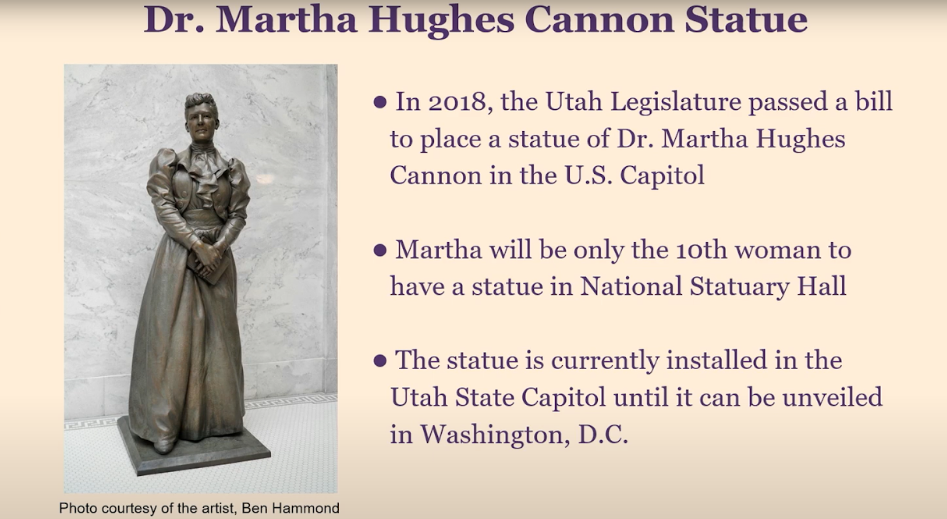

Honoring Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon

In 2018, the Utah Legislature passed a bill to place a statue of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon in National Statuary Hall in the rotunda of the U.S Capitol. Each state gets two statues to represent it, and once her statue is installed, Martha will be only the tenth woman in the collection. Because the unveiling ceremony was delayed by the pandemic, the Martha statue is currently installed in the Utah State Capitol. So, you can go and see this really stunning sculpture, and it will be there until it can be unveiled in Washington, D.C. whenever the capital opens up again for that.

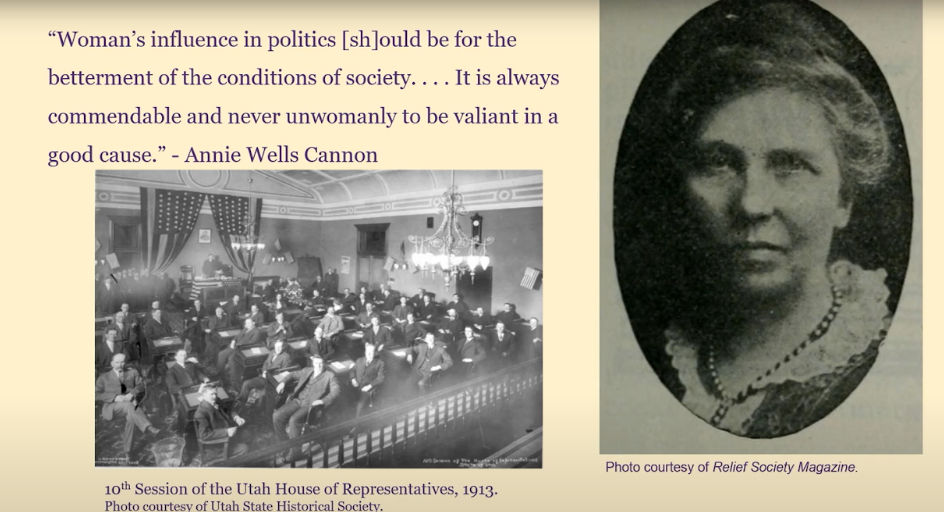

Annie Wells Cannon

This is Annie Wells Cannon; she’s the daughter of Emmeline B. Wells and she also served two terms in the state legislature in the early 20th century. Annie had 12 children, and she served in other leadership positions too, such as in the Relief Society on the Relief Society General Board, and as a Relief Society Stake President. For years, she was a leader in the American Red Cross and the National Women’s Party, which was the more radical of the national suffrage organizations.

That is an interesting side story as well with her. She spoke out against the wage gap and called for a minimum wage for women; this was a big issue at the time. She urged also that women’s influence in politics should be for the betterment of the conditions of society and that it’s always commendable and never unwomanly to be valiant in a good cause.

Elected Women

By 1920, when many women in the nation were first able to run for elected office, Utah had already elected two women state senators, 14 women to the state House of Representatives, and over 120 women to county offices. These women used their elected positions to introduce and secure passage of legislation that was designed to reduce inequities, including minimum wage laws, child labor laws, free kindergarten, a widowed mother’s pension, equal guardianship rights, prohibition, and nine-hour workday limits for women. It also included issues that mattered a lot to those individual women that were kind of the impetus for them getting involved.

With Martha Hughes Cannon, her public health bill, because of her medical training, was vastly important to her, and she worked really hard to get it. And Alice Merrill Horn was in the House at the same time that Martha was in the Senate, and they worked together to coordinate to get Alice’s art bill to institute the first state institute of art in the nation. The Alice Art Collection, you might have heard of, and so they worked together to ensure that their respective seats in government would pass those laws that mattered so much to them.

Federal Suffrage Amendment Efforts

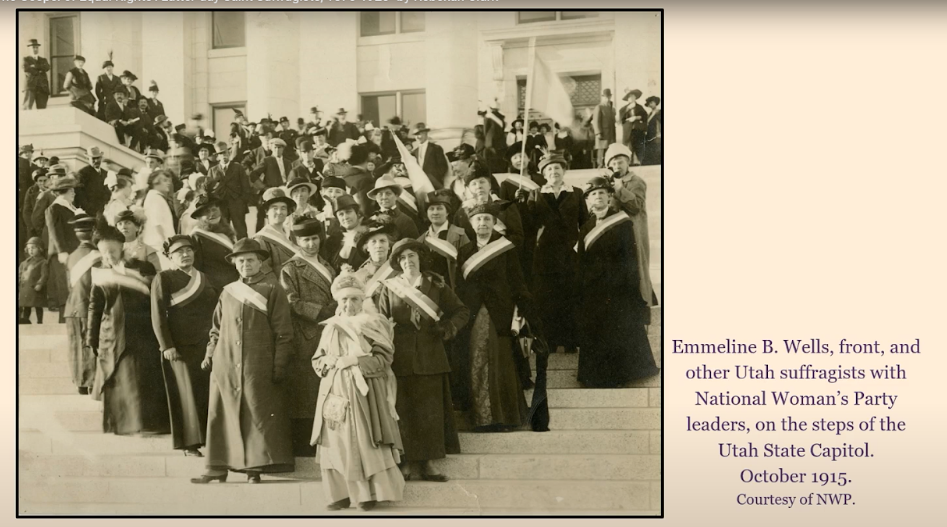

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Utah suffragists also supported efforts to obtain a federal suffrage amendment. They sent delegates to annual suffrage conventions, spoke to congressional committees on behalf of a constitutional suffrage amendment, gathered tens of thousands of signatures for congressional petitions, and participated in public demonstrations.

I love this image on the steps of the Utah State Capitol in 1915. Because Utah’s suffrage story began so early, it’s one of the few extant photographs that we have showing Utah suffragists with those iconic suffrage sashes and banners. On this day, Utah suffrage greeted a national suffrage envoy from the Congressional Union, the precursor to the National Women’s Party.

They were transporting a monster petition across the country to present to Congress on behalf of a suffrage amendment, and they paraded down Main Street with the Utah suffragists in Salt Lake City. It ended with this elaborate celebration at the State Capitol that featured the governor, Emmeline Wells, national leaders, and the Salt Lake City mayor. Having personally experienced the weakness of legislatively granted suffrage rights when they had their rights taken away from them, Latter-day Saints suffragists were, I think, even more particularly focused on advocating for a constitutional amendment.

Broad Support

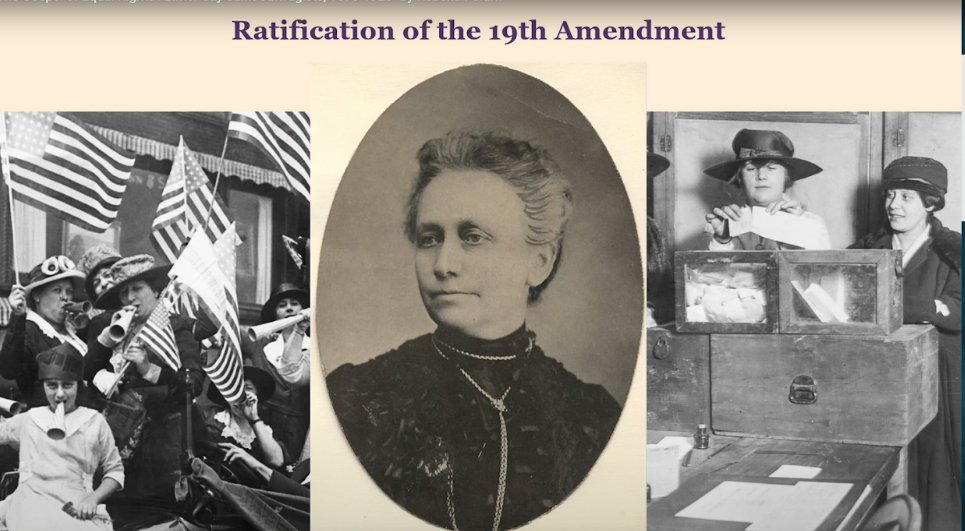

In 1919, Utah State Senator Elizabeth Hayward, an active Latter-day Saint, had the honor of introducing the bill to ratify that federal suffrage amendment in Utah. It passed within 30 minutes; there was just such broad support at this point. Women had been voting here for so long, when the 19th amendment finally became law in 1920, 50 years after Utah women had first begun to vote, Utah men and women celebrated with a large parade. They gathered again on the steps of the Utah Capitol, taking pride in the role they had played in this historic reform movement.

At the October general conference, just after the ratification of the 19th amendment, President Heber J. Grant stood at the pulpit and expressed his pleasure that the women of America had been granted the franchise. However, even with this victory, Utah’s suffrage story was not over; the work was not over. The 19th amendment was a landmark expansion of rights, but it also had significant limitations.

Restrictions

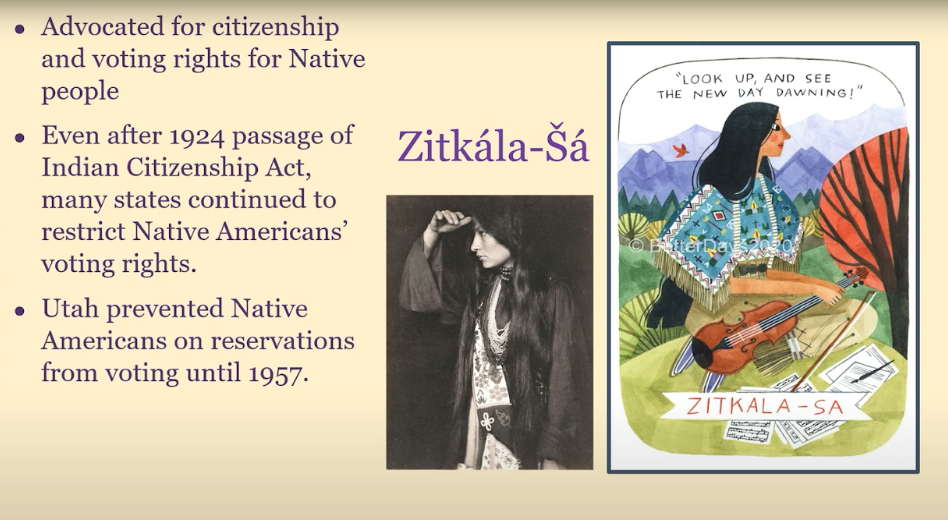

Federal restrictions on citizenship for native people and immigrants of Asian descent meant that women, as well as men in these communities, were still largely excluded from voting for many years, even decades. Utah women like Zitkala-Sa helped advocate for key federal legislation granting citizenship and accompanying voting rights for her people. Congress ultimately passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, but many states, including Utah, continued to restrict native people’s access to the polls. In fact, Utah had a law on the books until 1957 that prevented Native Americans living on reservations from voting.

Even after the 19th amendment, discriminatory voter registration laws were familiar, effectively excluding many African-Americans from voting in various parts of the nation, until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Even when voting was accessible, people of color often faced many other forms of inequity and discrimination in their communities.

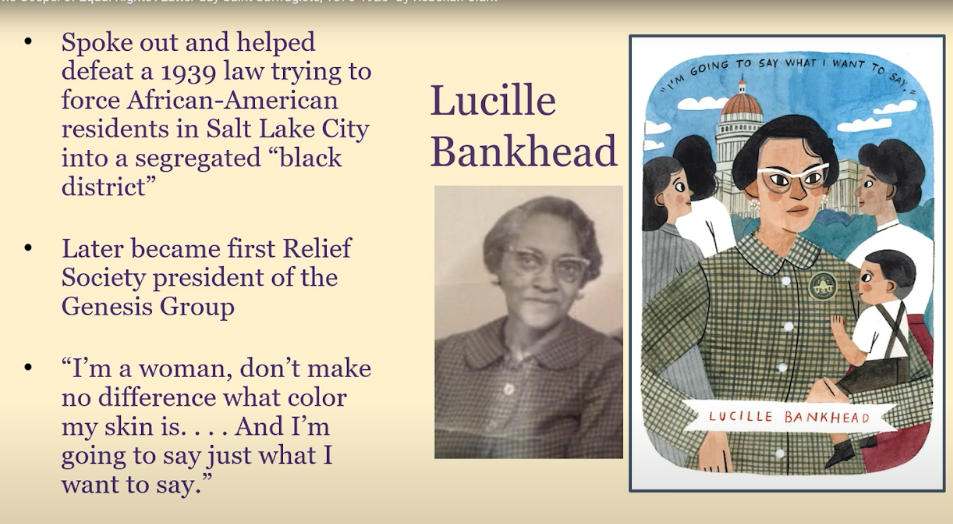

I love the story of Lucille Bankhead, a Latter-day Saint woman who later became the first Relief Society president for the Genesis Group. In 1939, she used her political voice to stand up against a proposed law that would have forced African-American residents in Salt Lake City into a segregated black district. Lucille helped defeat this bill by going up to the state capitol, which she had never been to before, and refused to leave until the legislature would listen to her arguments against the bill. Her leadership and willingness to stand up against injustice directly benefited her community and the state.

Conclusion

These women matter, and their contributions matter. Their stories matter, giving us examples of women whose leadership, courage, and faith forged new paths to improve their communities. Their paths can illuminate our own. If you haven’t gone to the Church History Museum yet this year to see the Sisters for Suffrage exhibit, I highly recommend it. It’s wonderful.

While you’re there, don’t miss the new Women’s History Memorial unveiled last August in commemoration of the centennial of the 19th amendment. It’s right across the street from the state capitol, in front of Council Hall, where Seraph Young cast that first historic vote. Designed to be an interactive experience, it incorporates many details from Utah’s suffrage story, including Seraph’s footprint, quotes from Utah suffragists, and four expanding door frames engraved with key pieces of federal legislation that extended voting rights. The path continues beyond these frames, signifying that we are each part of the continuing journey toward equality and justice that began here in Utah so many years ago.

Emmeline B. Wells wrote in 1911 that she hoped future historians would “remember the women of Zion when compiling the history of this western land.” Our book, Thinking Women, and our work at Better Days is a piece of that process of reinserting Utah women’s voices back into the narrative.

Do Not Fear History

I mentioned at the beginning that kind of nagging question of why hadn’t I been told this sooner. I think sometimes history scares people, especially women’s history and especially the history of women in the Church. It can be tricky, inconsistent, and hard to place into historical context without applying our current perspective. We shouldn’t be afraid of history. Starting from a place of faith is critical with any questions, especially as we are looking at Church history. If we start from a place of faith and then dive deep, this history helps us better understand our voices, identities, and potential through the lens of the women who have come before us.

Exploring the successes of our path and the work that still remains can help us make society better for all people in the future. It can challenge and inspire us to follow their legacies and make our presence felt, ensuring our voices are heard today.

So, in other words, let us apply the wisdom given by Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, when she said, “Let us not waste our talents in the cauldron of modern nothingness, but strive to become women and men of intellect and endeavor to do some little good while we live in this protracted gleam called life.” Thank you.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you, Rebekah. That was really interesting. That was wonderful. I’m always struck by how the world has changed, you know, and when people talk about the oppression of women and such, I would venture to say that it was true that the women were not given equal rights. It was not fair; life was not fair for them. And so, I think it’s important we maintain those histories so we can look back and see where we’ve come from, partly to see how far we’ve come, and hopefully, we’ll continue to move forward in some of those things. So here are the questions.

How important was polygamy in making Utah first in women getting the vote? Do you think it would have happened without polygamy?

Rebekah Clark:

That’s an excellent question because Utah suffrage was completely, inextricably linked with polygamy right from the start. It was actually first suggested to give women in Utah the right to vote by the New York Times. This was a theory that started in Congress, and their thought was if you give women in Utah the right to vote, they’re going to overthrow polygamy. And it was also kind of an easy way to test out women’s suffrage in a place they didn’t really care about. This was in the late 1860s, and Utah leaders, the Utah legislature, really called their bluff and turned it on its head. They unanimously passed the law and did so with full confidence that the women here would act in partnership with them and act in faith to defend their religious rights.

Scott Gordon:

Interesting. So are there any lists of Utah suffragettes where we can find out if relatives were in fact active in the movement?

Rebekah Clark:

We have been working on compiling those lists. If you go to (this is our plug for our education website) utahwomenshistory.org, we have a local history section where we have divided out by county different events and key people in those counties. And we are trying to build that as much as we can. We have at one point had a project that we were going to be doing with Ancestry. So that would be like you know, ‘I had an ancestor on the Mayflower.’ We really envisioned being able to have this, “You have a suffrage ancestor,” and that didn’t pan out the way that we had hoped, but we have been trying to compile those names, and really it’s just excavating them from old documents, from minute books, and especially the Women’s Exponent is just the most fabulous resource.

Scott Gordon:

Did Utah offer more educational opportunities for women than other states, or was it the influence of the gospel that helped fuel the suffrage movement?

Rebekah Clark:

So there definitely was an element that was unique to Utah. And as you get into the late 1860s, you have President Brigham Young and then Eliza R. Snow really encouraging women here to go to medical school and to become trained in professions and to have those marketable skills and to get education. There was a high value placed on education for women as well as men that were not necessarily available. And also, you can’t ignore the fact that many of those women who went to medical school were able to do so because they were polygamous women who had sister wives who had some families where they took turns in child care. Yeah.

Scott Gordon:

Would our LDS suffragist sisters be supportive of the present effort to pass the constitutional amendment for equal rights for women, the ERA?

Rebekah Clark:

That is such a good question. I would like to know, and I think as I have studied this history, I don’t think you can give a definitive answer lumping them all together. What I have seen is that these women were all highly, and first and foremost, motivated by their faith and that when push came to shove, they would always choose their faith in defending the Church over any of the other issues that they advocated. So I think that they would listen carefully to what the brethren have taught us on that.

But we also see a lot of disparity within those women. Even like Emily S. Richards, who was the president of the Utah State Suffrage Association for the two decades leading up to the 19th amendment, Annie Wells Cannon who was on the Relief Society General Board with her, and they were close friends. Annie Wells Cannon was also on the National Advisory Board for the National Women’s Party, which was started by Alice Paul, the author of the first Era. So, you know, if I could sit down with Annie Wells, I would love to ask her that. Interesting.

Scott Gordon:

Finally, I have this question and then one more. What do you love so much about Emmaline B Wells?

Rebekah Clark:

Emmaline was really the first of these women that I got to know intimately. When I was doing my thesis research, I would go to special collections down at BYU. I came out for a whole summer so that I could pour through her journals. I was astounded by her faith, but also the hardships that she went through personally in her life. Just so much heartbreak. But her resilience, creativity, leadership, and just the energy of this little woman—she was five foot nothing and had, according to all accounts, the best memory of anyone. Anyone who knew her or anyone else. She was involved in so many different boards, activities, and service organizations. She was constantly going to meetings and doing things and then being the General Relief Society President. She just was unstoppable. It’s amazing. There are so many amazing people in history we can read about.

Scott Gordon:

The final question is, you have a book out, right? What is the name of that book?

Rebekah Clark:

Thinking Women.

Scott Gordon:

And you will be sitting outside the door and willing to sign that book.

Rebekah Clark:

I will. I would love to sign that book for anyone who wants it. It’s a beautiful book.

Scott Gordon:

Cool. Good. So thank you very much.

coming soon…

Were Latter-day Saint women truly leaders in suffrage?

Yes, Utah women were among the first to vote, held leadership movements, and saw their activism as part of their faith.

Did polygamy hinder or help women’s rights?

While controversial, plural marriage gave many Latter-day Saint women increased autonomy and public engagement, fueling their leadership in the suffrage movement.

Latter-day Saint women as pioneers in both faith and activism.

The intersection of religious belief and political advocacy.

The contributions of Relief Society leaders to national women’s rights movements.

Share this article