FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

O Livro de Mórmon nome "Nahom" torna-se NHM quando escrito em hebraico. Esta é uma correlação significativa em nome e localização.

Três inscrições altar foram descobertos contendo o nome "NHM" como um nome tribal e datado do sétimo para sexto séculos aC. Isto é aproximadamente o período de tempo em que a família de Leí estava viajando embora da mesma área.

S. Kent Brown: [1]

Em um exemplo, no entanto, Néfi faz preservar um nome local, que de Nahom, o local de sepultamento de Ismael, o pai-de-lei. Néfi escreve no passivo, "o lugar que era chamado Nahom", indicando claramente que a população local já havia chamado o lugar. Que esta área estava no sul da Arábia foi certificado pelas recentes publicações Journal que contou com três altares de pedra calcária com inscrições descoberto por uma equipe de arqueólogos alemães no templo em ruínas de Bar'an em Marib, no Iêmen.[2] Aqui uma pessoa encontra o nome tribal NHM observado em todos os três altares, que foram doados por uma certa "Bicathar, filho de Sawad, filho de Nawcân, o Nihmite." (Em línguas semíticas, um lida com consoantes em vez de vogais, neste caso NHM).

Tais descobertas demonstram tão firme quanto possível por meio arqueológica da existência do nome tribal NHM em que parte da Arábia no sétimo e sexto séculos aC, as datas gerais atribuídos à escultura dos altares pelas escavadoras.[3] Na visão de um comentador recente, a descoberta dos altares equivale a "a primeira evidência arqueológica real para a historicidade do Livro de Mórmon".[4]

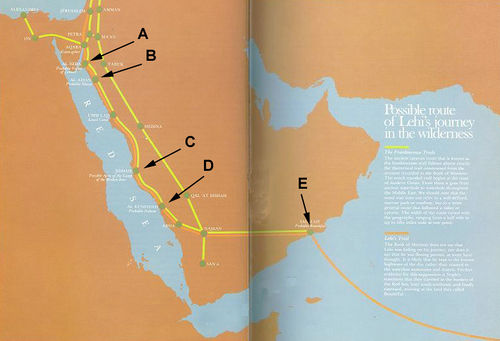

A rota das especiarias proceder ao sul de Jerusalém e então se vira para o oriente no local onde as inscrições NHM foram encontrados. O grupo de Leí passou para o sul e, em seguida, fez uma mudança "para o leste", em direção depois de deixar o "lugar que foi chamado Nahom."

E aconteceu que reiniciamos a jornada pelo deserto e, dali em diante, viajamos na direção aproximada do leste.

S. Kent Brown:

O caso de Nahom, ou NHM, nesta área é ainda mais apertado por estudo recente. Tornou-se claramente da nota- de Néfi "que viajava quase para o leste" do Nahom (1 Néfi 17: 1) -que ele e seu partido não só tinha ficado na área tribal do NHM, enterrando Ismael lá, mas também estavam seguindo ou sombreando o rastro de incenso, uma estrada de negociação que por então, ofereceu uma infra-estrutura de poços e forragem para os viajantes e seus animais. Da região geral da tribo NHM, todas as estradas virou leste. Como assim? Do outro lado do deserto Ramlat Sabcatayn, a leste desta região tribal e leste de Marib, estava a cidade de Shabwah, agora em ruínas. Por lei árabe antiga, era a esta cidade que todos incenso colhida nas terras altas do sul da Arábia foi levada para inventariar, pesagem e tributação. Além disso, os comerciantes fizeram presentes de incenso aos templos em Shabwah.[5] Após este processo, os comerciantes carregado o incenso e outros bens em camelos e enviado-os para as zonas mediterrânicas e da Mesopotâmia, viajando a primeira para o oeste e, em seguida, depois de atingir as bordas da região da tribo NHM, voltando para o norte (estas instruções são exatamente opostas daqueles que Néfi e seu partido seguido). Mesmo os atalhos assustadores através do deserto Ramlat Sabcatayn, o que deixou os viajantes sem água para 150 milhas, correu em geral leste-oeste. O que é importante para os nossos propósitos é o fato de que a sua vez "para o leste" da narrativa de Néfi não aparece em nenhuma fonte antiga conhecida, incluindo Plínio a famosa descrição da pessoa idosa das terras-incenso crescente da Arábia. Em uma palavra, ninguém sabia desta vez para o leste na trilha de incenso, exceto pessoas que viajaram ou que viviam nesse território. Este tipo de detalhe no livro de narrativa Mórmon, juntamente com a referência à Nahom, é uma informação que não estava disponível na época de Joseph Smith e, portanto, fica como prova convincente da antiguidade do texto.[6]

Néfi indicou que seu grupo tinha chegado a um "lugar que era chamado Nahom", indicando que o site já foi nomeado. Ismael foi enterrado lá, e suas filhas choraram ele lá.

E aconteceu que Ismael morreu e foi enterrado no lugar chamado Naom. E aconteceu que as filhas de Ismael choraram muito a perda de seu pai...

Os críticos da Igreja tentativa para descartar essa correlação simplesmente como "a disposição dos estudiosos SUD olhar para qualquer lugar em seu desespero para encontrar um pingo de validação para suas crenças errôneas." [7] No entanto, dada a elevada correlação dos dados, parece que os críticos são os que têm dificuldade em explicar os dados.

Vários sites que são críticos da Igreja apresentaram o seguinte argumento:[8]

Esta [FairMormon] link menciona livros de Niebuhr e d'Anville das. Ele também diz que nem estavam em Dartmouth quando Joseph era um menino, nem foram disponível em Manchester, New York na biblioteca de empréstimo.

Agora, para o resto da história. Allegheny College em Meadville Pennsylvania é cerca de 50 milhas do Harmony. Sua biblioteca começou através de doações de particulares. Em 1824, Thomas Jefferson escreveu que ele esperava que sua universidade de Virgínia poderia um dia possuir a riqueza da biblioteca de Allegheny.

Na coleção do Allegheny eram ambos os livros que os apologistas afirmam não estavam disponíveis para Joseph Smith. Aqui está um catálogo de 1823:

O livro de D'Anville em geografia antiga está na página 18

Niebuhr is on page 44

Ambos os livros foram 50 milhas de distância de onde a tradução estava sendo feito.

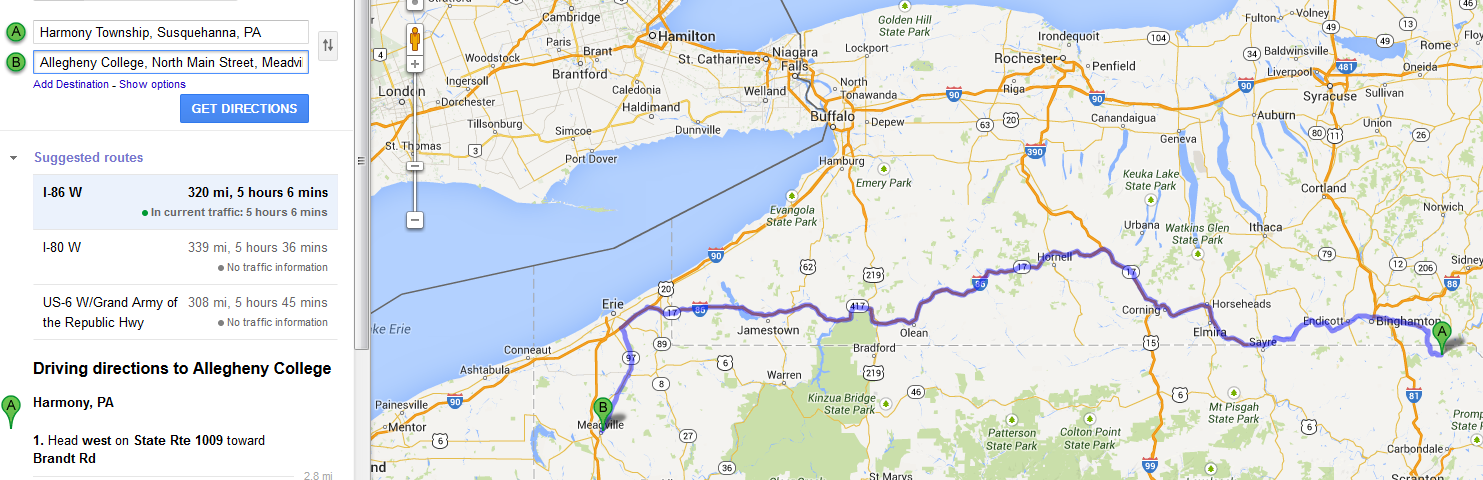

Na verdade, a cidade de "Harmony" localizado a 50 milhas de Allegheny College é não o mesmo que o Township Harmony, onde Joseph Smith viveu. Com efeito, se a pessoa simplesmente tipos "Harmony, Pensilvânia" no Google Maps, ela indica que uma cidade chamada "Harmony" está localizado a aproximadamente 50 milhas de Allegheny College, em Meadville. No entanto, os críticos entenderam errado. O Township Harmony em que viveu José está localizado 320 milhas de Allegheny College. Isto é facilmente confirmado, digitando "Harmony Township, Susquehanna, PA" no Google Maps.

FairMormon reconheceu que dois livros estavam disponíveis no Allegheny College em Meadville Pennsylvania contendo mapas que mostram a localização de Nahom (alternativamente soletrado NIHM ou Nehem). Concluímos que, apesar de esses livros estavam presentes, que eles não foram localizados perto o suficiente para Harmony Township por Joseph ter utilizado-los. Os críticos, no entanto, parecem ter utilizado uma pesquisa com defeito Google para afirmar que estes livros foram localizado perto o suficiente para que Joseph Smith viveu para ele tê-los usado. Por exemplo, o site crítica MormonThink tentou refutar o argumento de FAIRMormon em sua página de "Book of Mormon Problemas". MormonThink declarou em junho de 2014: "Agora para o resto da história Allegheny College em Meadville Pennsylvania é cerca de 50 milhas de Harmony ... Na coleção do Allegheny eram ambos os livros que os apologistas afirmam não estavam disponíveis para Joseph Smith..." No entanto, após Neal Rappleye e Stephen Smoot salientou no documento intitulado "Livro de Mórmon minimalistas e as inscrições NHM: Uma Resposta a Dan Vogel", que os críticos tinham selecionado o errado cidade de Harmony para sua busca mapa do Google, MormonThink retirou o pedido e já não aparece a partir de outubro de 2014. A alegação ainda aparece em pelo menos um outro site crítica.[9]

Portanto FairMormon mantém a sua afirmação de que Allegheny College, a 320 milhas de distância, foi muito longe do Harmony Township por Joseph ter visto o nome de "Nahom" em um dos mapas ali localizados.

S. Kent Brown:

The entire thrust of these remarks underscores the observation that Joseph Smith could have known almost nothing about ancient Arabia when he began translating the Book of Mormon. Yet the narrative of the journey of the party of Lehi and Sariah through ancient Arabia, written by their son Nephi, fits with what we know about the Arabian Peninsula literally from one end to the other, for their journey began in the northwest and ended in the southeast sector. Nephi's narrative faithfully reflects the intertwining of long stretches of barren wilderness with pockets of verdant, lifesaving vegetation. Recent discoveries have illumined segments of the account, tying events to known regions (e.g.,) and climatic characteristics (e.g., mists along the coastal mountains). People in Joseph Smith's world may have possessed accurate information about one or two aspects of Arabia through classical sources (e.g., incense trade, honey production). But those same sources offered inaccurate caricatures of Arabia that Nephi's narrative does not mirror (e.g., that the peninsula was graced by large forests, etc.). Hence, on both fronts—modern discoveries and more accurate information—the Book of Mormon account shines as a radiant beam across the centuries, inviting us to adopt its more important message of spiritual truths as our own.[10]

Stephen D. Ricks: [11]

Surprisingly, evidence for Nahom, the name of the place where Ishmael was buried (1 Nephi 16:34), is based on historical, geographic, and archaeological—and only secondarily on etymological—considerations.

Three altar inscriptions containing NHM as a tribal name and dating from the seventh to sixth centuries BC—roughly the time period when Lehi’s family was traveling though the area—have been discussed by S. Kent Brown.[12] Dan Vogel, writing in the misleadingly named Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet and responding to two books by LDS authors about Lehi’s journey in the Arabian desert, has objected to the dating of the Arabian word NHM: “There is no evidence dating the Arabian NHM before A.D. 600, let alone 600 B.C.” [13] It should be noted, however, that Burkhard Vogt, perhaps unaware of its implications for the Book of Mormon, dates an altar having the initial letters NHM(yn) to the seventh to sixth centuries BC. [14] This is not insignificant since Vogel’s book was published in 2004, while Vogt’s contribution was published in 1997.Nhm appears as a place name and as a tribal name in southwestern Arabia in the pre-Islamic and early Islamic period in the Arab antiquarian al-Hamdani’s al-Iklīl [15] and in his Ṣifat Jazīrat al-’Arab. [16] If, as Robert Wilson observes, there is minimal movement among the tribes over time, [17] the region known in early modern maps of the Arabian Peninsula as “Nehem” and “Nehhm” as well as “Nahom” may well have had that, or a similar, name in antiquity.

S. Kent Brown:

The case for Nahom, or NHM, in this area is made even more tight by recent study. It has become clearly apparent from Nephi's note—"we did travel nearly eastward" from Nahom (1 Nephi 17:1)—that he and his party not only had stayed in the NHM tribal area, burying Ishmael there, but also were following or shadowing the incense trail, a trading road that by then offered an infrastructure of wells and fodder to travelers and their animals. From the general region of the NHM tribe, all roads turned east. How so? Across the Ramlat Sabcatayn desert, east of this tribal region and east of Marib, lay the city of Shabwah, now in ruins. By ancient Arabian law, it was to this city that all incense harvested in the highlands of southern Arabia was carried for inventorying, weighing, and taxing. In addition, traders made gifts of incense to the temples at Shabwah.[18] After this process, traders loaded the incense and other goods onto camels and shipped them toward the Mediterranean and Mesopotamian areas, traveling at first westward and then, after reaching the edges of the region of the NHM tribe, turning northward (these directions are exactly opposite from those that Nephi and his party followed). Even the daunting shortcuts across the Ramlat Sabcatayn desert, which left travelers without water for 150 miles, ran generally east-west. What is important for our purposes is the fact that the "eastward" turn of Nephi's narrative does not show up in any known ancient source, including Pliny the Elder's famous description of the incense-growing lands of Arabia. In a word, no one knew of this eastward turn in the incense trail except persons who had traveled it or who lived in that territory. This kind of detail in the Book of Mormon narrative, combined with the reference to Nahom, is information that was unavailable in Joseph Smith's day and thus stands as compelling evidence of the antiquity of the text.[19]

Nephi's party reaches an area "which was called Nahom" (1 Nephi 16:34)near the time that they make an eastward turn in their journey. [20]

It [the root for naham] appears twenty-five times in the narrative books of the Bible, and in every case it is associated with death. In family settings, it is applied in instances involving the death of an immediate family member (parent, sibling, or child); in national settings, it has to do with the survival or impending extermination of an entire people. At heart, naham means "to mourn," to come to terms with a death; these usages are usually translated...by the verb "to comfort," as when Jacob's children try to comfort their father after the reported death of Joseph. [21]

It is intriguing that Nephi tells us that the deceased Ishmael was buried at a spot with a name associated with mourning and death of loved ones.

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now