August 5, 2016

[Download PowerPoint presentation (pdf)]

Overview

Many of our discussions about the translation of the Book of Mormon mention the Nephite Interpreters, and the Seer Stone in the Hat. We have discussions about whether there was a curtain present during the translation. Sometimes we discuss potential anachronisms – like the inclusion of ideas from the New Testament, the use of the King James language and textual reliance on the King James translation. Only very rarely do we find discussions of issues significant to translators: do we ever discuss whether the Book of Mormon is a formal equivalence translation or a dynamic equivalence translation? When we speak of translation, we tend to focus more on a description through the eyes of an observer, and less on what it means that the text is a translation in the first place.

My presentation this morning is about translation – but it is about translation as explained through speech act theory as a communicative act. In introducing translation in this way, I hope to build a useful framework – both for understanding the range of explanations we have built about the translation of the Book of Mormon, and also to build more constructive answers to the challenges we confront when we look at the text from the perspective of a translation.

However, in order to move past some of the earlier explanations and approaches, it is necessary to spend some time dealing with them, and eventually, to show how these approaches can be reframed by the tools that I bring to the question of translation.

Translation – An Introduction to the Problem

In 2003, Glen Scorgie contributed to a volume on Biblical translation from an Evangelical perspective. He began by discussing some of the challenges caused by popular Evangelical (mis)conceptions of translation. He wrote:

According to the historic evangelical view, divine inspiration is more than a general influence over the biblical authors as a whole; inspiration extends to the micro-level of the very words found in the original text. This is an important doctrine for evangelicals, and it needs to be maintained. But at this point the reasoning of some (not all) conservative evangelicals begins to shift from defensible doctrine to questionable inference. Each individual word of Scripture, the questionable reasoning suggests, was specifically selected by God and delivered to us from above in a manner very similar to dictation. The words were sent down, one at a time, like crystal droplets. Each word is an autonomous integer, separate from the rest, and each is to be treasured like a sacred gem and cherished inviolate for all time.[2]

Similarly, Mormonism’s popular view of the Book of Mormon occupies some of this same space. After all, we have a dictation process, we have revelation that potentially provides not only the specific words used, but, is capable of correcting mistakes (at least in the original text). And because of this, we often assume some sort of word-for-word translation has happened with the text. This is not so different from this Evangelical perspective. Scorgie starts with this idea of divine scripture and then extends this to an idea of divine translation. He continues:

When it comes to translation preference and practice, the implications of this way of thinking are predictable. Those who view Scripture this way (and not all evangelicals do, of course) favor attempts at word-for-word translation. Translations produced in this fashion are naively thought to retain all the precious original words, except that they are just in a different code now. The inclination is to assume that in every language there is a template of more or less exact equivalents to the inspired Hebrew and Greek words with which we started out. This is, of course, not the case at all. If evangelicals are to get beyond their current impasse over translation theory, they will need a more profound doctrine of biblical inerrancy—one that continues to respect the inspired words of the original text but also acknowledges that these words are mere instruments in the service of a higher purpose, namely, the communication of meaning.[3]

Our LDS view of the Bible and its translation has changed somewhat over time. In the King Follett Discourse, Joseph Smith noted that the best translation of the New Testament that he had found was an old German translation by Luther. The King James wasn’t held in particularly high regard in early Mormonism – it was the only English text that most readers knew in the 19th century. A second major English translation, the Revised Version, wouldn’t be completed until 1885. When it was published, it contained tens of thousands of changes from the King James text, and those changes caused concerns for many believers. It was in this context (and because some of these changes impacted proof texts used by the Church) that the LDS Church leadership first came out in strong support for the King James text. This legacy remains with us, as the current statement on the subject from the Church reads in part:

All of the Presidents of the Church, beginning with the Prophet Joseph Smith, have supported the King James Version by encouraging its continued use in the Church. In light of all the above, it is the English language Bible used by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

This is a little bit misleading, since Joseph Smith (with the rest of the early LDS leadership) supported the use of the King James text out of necessity and not necessarily out of choice. My concern though isn’t simply the adoption of the King James translation, but rather the adoption of much of what was being said about the King James and it’s translation by non-LDS contemporaries. These are the kinds of ideas introduced by Scorgie, and the kinds of ideas that remain with us today – both in our view of Biblical translation and in our view of Book of Mormon translation.

Stephen Ricks, in a short note in the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies confronted the same sorts of challenges that Scorgie addresses when he discussed David Whitmer’s description of the translation of the Book of Mormon:

This statement is somewhat problematical from a linguistic point of view. It suggests a simple one-for-one equivalency of words in the original language of the Book of Mormon and in English. This is scarcely likely in two closely related modern languages, much less in an ancient and modern language from two different language families. An examination of any page of an interlinear text (a text with a source language, such as Greek, Latin, or Hebrew, with a translation into a target language such as English below the line) will reveal a multitude of divergences from a word-for-word translation: some words are left untranslated, some are translated with more than one word, and often the order of words in the source language does not parallel (sometimes not even closely) the word order of the target language. A word-for-word rendering, as David Whitmer’s statement seems to imply, would have resulted in a syntactic and semantic puree.[4]

We could extend this idea even further. If we follow what the text of the Book of Mormon seems to suggest, then the Isaiah passages that Nephi quotes come from an Egyptian text, which was translated from a Hebrew original. That Egyptian text is then translated into the language on the gold plates, which is then translated into English in the Book of Mormon into a nearly exact copy of the King James translation. Is this really likely?

Whitmer’s statement was published in 1887. In my opinion, it is not coincidental that this statement and the others discussed by Ricks all come shortly before and after the publication of that next major English translation. They are, I think, not just a part of our LDS discussion about the translation of the Book of Mormon, they participate in that larger discussion on the question of biblical translation and divine scripture.

In contrast, Royal Skousen took a very different approach to these statements in his 1998 essay titled “How Joseph Smith Translated the Book of Mormon: Evidence from the Original Manuscript”[5].

The manuscripts and text show that Joseph Smith apparently received the translation word for word and letter for letter, in what is known as “tight control.”

These two competing views highlight some of our core interest. Is the translation human? Is it divine? And can the text and the manuscripts really tell us much at all about the process of translation? The focus for earlier discussions about the Book of Mormon have all focused on the text that we have. But this text comes as a product of whatever process of translation occurs. It cannot reveal nearly as much about the translation process as Skousen suggests.

Historically, part of our struggle with the question of translation comes from the comparisons we make between the text of the Bible and the text of the Book of Mormon. We can see this in the subtitle of the current edition of the Book of Mormon. The phrase “Another Testament of Jesus Christ” explicitly invites such a comparison. And we find all sorts of other markers used in that comparison, whether it is the visual cue of versification added in the 1879 edition, or the image of the Book of Mormon as the stick of Joseph from Ezekiel’s vision, introduced to the Saints in the writings of William Phelps in 1833. Most of the time, this comparison works well and helps those we introduce to the Book of Mormon understand how we use and understand the Book of Mormon within our faith. But, when we take this comparison, and extend it into studies of the text, it can create some very real problems. Our tendency to try and understand the Book of Mormon and its translation primarily through the lens of biblical studies and the tools employed within traditional biblical studies is part of this inadequate framework.

I will argue that the text of the Book of Mormon – even the various manuscript copies, is the end result of this process of translation, and really cannot answer many of the questions we put forward. We also have to consider the various other forces at work – and these forces can be identified through speech act theory.

The Gift and Power of God

How does Joseph Smith describe the translation process? At the end of June, in 1829, the Three Witnesses were allowed to see the gold plates. In the statement that they signed, it tells us of the translation process that:

The Book of Mormon is a record of the forefathers of our western tribes of Indians; having been found through the ministration of an holy angel, and translated into our own language by the gift and power of God.[6]

At some point in August of 1829, Joseph Smith with perhaps the assistance of Oliver Cowdery, wrote the preface to the first edition of the Book of Mormon. In it we have this statement:

I would inform you that I translated, by the gift and power of God, and caused to be written, one hundred and sixteen pages, the which I took from the Book of Lehi, …[7]

And on November 9, 1829, Oliver Cowdery wrote, in a letter to Cornelius Blatchly, (on behalf of Martin Harris): “And he, by a gift from God, has translated it into our language.”[8]

On occasion, we also sometimes see references to the 1833 letter from Joseph Smith to Noah Saxton, however, this letter simply quotes from the published Testimony of the Three Witnesses.[9]

And there are other sources which use this same language to describe the translation of the Book of Mormon. And we all recognize that this language leaves something to be desired. Joseph did not seem interested in explaining in any greater detail, and perhaps many of you are familiar with the statement that he made to Hyrum in a Church conference in 1831:

it was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon; and…it was not expedient for him to relate these things[10]

Where does this language come from? It is taken from Omni verse 20:

And it came to pass in the days of Mosiah, there was a large stone brought unto him with engravings on it; and he did interpret the engravings by the gift and power of God.

When Joseph and those with him first articulate this formula, it comes right after the translation of Omni 1:20. Joseph employs this phrase as an allusion to the text of the Book of Mormon – that is, Joseph isn’t just interested in saying that there was a divine component to the translation process, he very much wants us to understand that he (Joseph) was functioning as a seer, just like King Mosiah, that his use of the interpreters was just like the use made in the Book of Mormon with reference to the Jaredite record, and so on. Since we rarely connect the two, the importance of the allusion to Joseph’s intention is often lost.[11] Why are these statements rather unsatisfying descriptions of the process? They are not used to describe the translation process.

At the same time, we tend to take a very literalist understanding of Joseph’s statement here. In a recent essay, Stanford Carmack tries to maintain this idea of Joseph as translator, even while minimizing his role in the process:

It is still appropriate to call Joseph Smith the translator of the Book of Mormon, but he wasn’t a translator in the usual sense of the term. He was a translator in the sense of being the human involved in transferring or re-transmitting a concrete form of expression (mostly English words) received from the Lord.[12]

When this was first published, I was reminded of a comment by Oliver Cowdery dealing with one of the earliest criticisms over the identification of Joseph Smith as the author of the Book of Mormon in the copyright statement. This statement was required by contemporary copyright legislation, but in making a formal response, Oliver quoted Webster’s 1828 dictionary:

Your first inquiry was, whether it was proper to say, that Joseph Smith Jr., was the author? If I rightly understand the meaning of the word author, it is, the first beginner, or mover of any thing, or a writer. Now Joseph Smith Jr., certainly was the writer of the work, called the book of Mormon, which was written in ancient Egyptian characters, – which was a dead record to us until translated. And he, by a gift from God, has translated it into our language. Certainly he was the writer of it, and could be no less than the author.[13]

Oliver suggests that while Joseph wasn’t the author in the usual sense of the term, he could nevertheless be called the author. While this sort of statement may be helpful in both circumstances as an apologetic argument, it isn’t helpful in understanding what is going on in either case.

Authenticity

The final complication I want to mention is the question of authenticity. Most often, our analysis of translation (and translation related issues) isn’t meant to describe the process of translation itself, but to try and move that process into the realm of proof of authenticity. In the statement above, Carmack suggests that we should view Joseph as a translator in name only. In fact, Carmack goes on to suggest that Joseph couldn’t have translated the text. And this becomes proof of authenticity. It makes for a strange proof of authenticity when we talk of a translation by arguing that we have no idea who the translator was, or how they did their job.

Another example of how we conflate translation with proof comes in the assumptions surrounding chiasmus. Earlier, I noted that we have a tendency to use the tools of biblical criticism to investigate the text of the Book of Mormon. When we apply these tools to the Book of Mormon, and get results that are similar to the results produced in Biblical Studies, we use these results to suggest proof of authenticity. I see this regularly in essays (both published and unpublished) exploring aspects of chiasmus. A recent favorite for chiamsus enthusiasts was the 2010 essay by Edwards and Edwards titled “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?”[14] This study is fascinating. It provides what could turn out to be a very valuable negative check to use against proposed examples of chiasmus in a text. But, it also has some issues related to its purpose (as an article). In the conclusions, they note this:

Using chiasmus to strengthen the claim of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon as an ancient historical record is based on the assumption that Joseph Smith was unaware of chiasmus.[15]

And this seems to be par for the course when we engage this topic. Biblical studies is, by definition, quite narrow. They have very little interest in (or need for interest in) chiasmus outside of their field of study. And so Edwards and Edwards wrote in their introduction that:

The historical record has yielded no direct evidence that Joseph Smith actually knew about chiasmus when he translated the Book of Mormon in 1829, although some other people at that time did.[16]

The study uses a footnote to point to a series of articles by Jack Welch, Don Parry, and Dan Peterson. And those articles are certainly worth reading. And of course, if we look for references to chiasmus, we are going to come up with a very short list (which these authors all do). In fact, the term chiasmus is really rather quite late. And in terms of Biblical studies this isn’t much of an issue. But, in modern literary studies we find the same concept under the label of ‘ring forms’ and ‘ring structures’. And we can find entire books written with a chiastic structure that are roughly contemporary with the publication of the Book of Mormon. The one that caught my attention first, and introduced me to this concept (as seen outside of the world of Biblical studies) was published by Giambattista Vico in 1710, titled Liber metaphysicus, (the first of three volumes in his De antiquissima Italorum sapientia).[17] Just as significant was the influence that Vico had on Wagner – his ring forms becoming the structure of Vagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung, his epic four part music drama composition. And Wagner’s work went on to inspire James Joyce – most notably in his novel Ulysses.

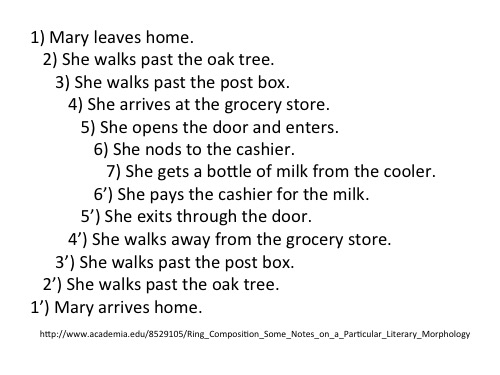

Of course, in the context of ring forms – especially canonical ring forms, the inclusion of these structures happens at the time of authorship – they are part of compositional frameworks, and not so much involved in the actual rhetoric of a piece (except indirectly of course, as the pattern once recognized can help us understand how the author relates various topics to each other). Macro-chiasmsus – including those found in the Book of Mormon suffer from the same kinds of issues. There is little doubt that the reason why long chiastic structures in the Book of Mormon are difficult to notice is precisely that they are long enough that the by the time we reach the end, the beginning is a distant memory. And the suggestion that the center is the most important idea is something of a circular reasoning created by our notion that the center should be the most important part. Bill Benzon provides something different for us in this example:

1) Mary leaves home.

2) She walks past the oak tree.

3) She walks past the post box.

4) She arrives at the grocery store.

5) She opens the door and enters.

6) She nods to the cashier.

7) She gets a bottle of milk from the cooler.

6’) She pays the cashier for the milk.

5’) She exits through the door.

4’) She walks away from the grocery store.

3’) She walks past the post box.

2’) She walks past the oak tree.

1’) Mary arrives home.[18]

Bill explains:

That’s a canonical ring form, with the departure from and arrival back home being the first and last elements in the ring and the purchase of the bottle of milk being the mid-point. The events in the tale are arrayed symmetrically about the mid-point.

And within a canonical ring form, the center isn’t necessarily the main point – it simply serves as the middle of the structure. My point here isn’t to contest the idea of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon. There seem to be some remarkable structures in the text. What I am suggesting is that the appearance of modern chiasmus – and in particular of these macro-chiastic structures, along with a body of literature describing them and their use, point to an unrecognized problem – biblical studies has no interest in modern literature, and so has never engaged the question of chiasmus as an established structure and form apart from its narrow interest in the ancient near east. And because this literature exists outside of the world of Biblical Studies, most Mormons engaged in these studies are simply oblivious to its existence. Chiasmus as a literary structure wasn’t as unknown in Joseph’s day as we sometimes like to believe. It just wasn’t always called chiasmus.

This doesn’t mean that Joseph had ever read Giambattista Vico or (if we followed the tortured logic of certain critics) had ever heard about his writings from someone who could read Italian and had a copy). What this illustrates for me is that these proposals about chiasmus in the Book of Mormon are far more interested in trying to create an argument for authenticity than they are trying to understand the text. These kinds of approaches (using the tools of biblical studies) tend to blur the distinction between the Book of Mormon as a modern text and its potential ancient sources.

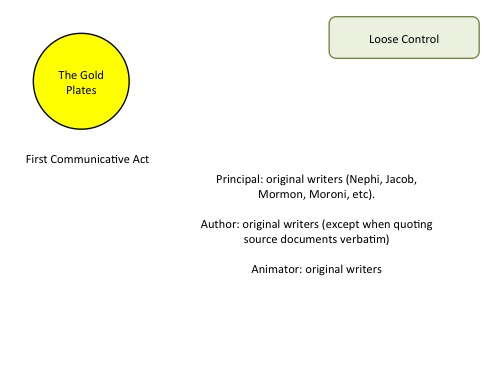

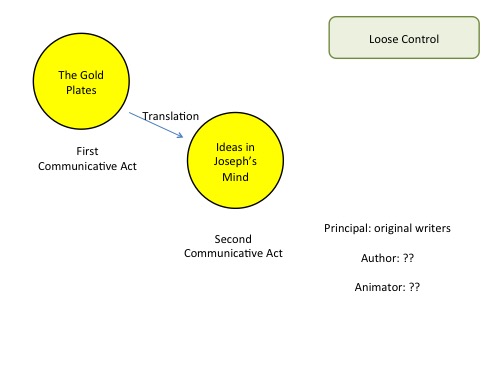

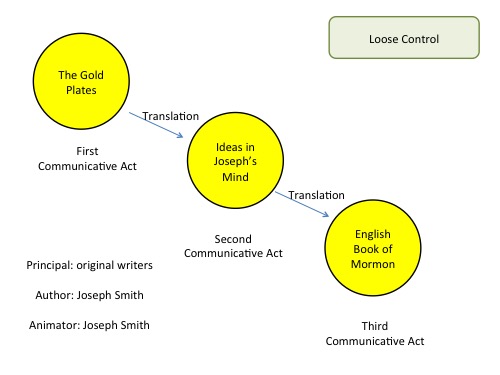

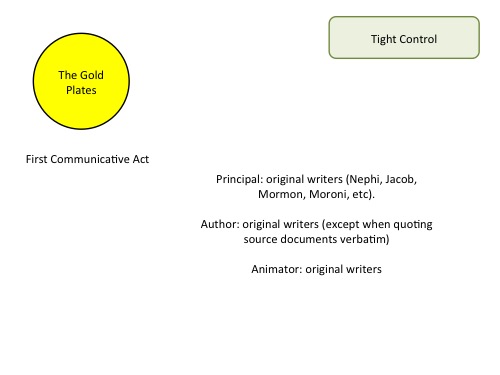

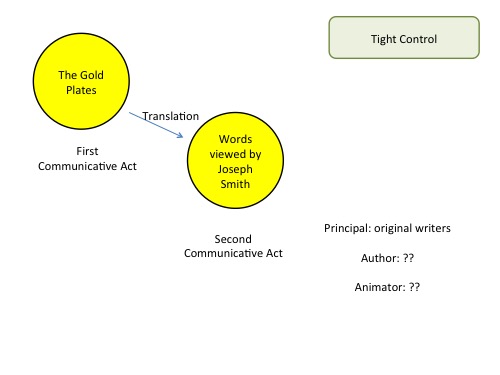

To help rebuild this distinction, I am proposing the following framework for discussing the translation of the Book of Mormon as a communicative act. As I introduce this framework, I am going to use it to analyze the models of dictation proposed by Royal Skousen in 1998.[19] Skousen describes what he identifies as three kinds of potential controls over the dictation of the text:

- Loose control: Ideas were revealed to Joseph Smith, and he put those ideas into his own language (a theory advocated by many Book of Mormon scholars over the years);

- Tight control: Joseph saw specific words written out in English and read them off to the scribe-the accuracy of the resulting text depending on the carefulness of Joseph and his scribe;

- Iron-clad control: Joseph (or the interpreters themselves) would not allow any scribal error to remain (including the misspelling of common words)

For my purposes today, there is very little difference between the notion of tight control and iron clad control – I will consider them as essentially the same process. I will start by identifying the participant roles.

Speakers

For those of you who are unfamiliar with speech act theory, this theory deals with communicative acts – not just what we say, but what we do by saying it. When I first became interested in the theory, I was exploring the idea with an interest related to my day job in technology.

What fascinated me were spam e-mails, generated by algorithm, with the intention of sneaking through a spam filter with some sort of payload (a virus, a phishing link, an offer to become a business partner with some former dignitary in Nigeria). So these algorithms attempted to simulate real e-mails to try and fool the spam detection algorithms. Of course, technology changes have to some extent changed the problem quite a bit in the last decade, but at the time, there was something of a race between these spammers building more sophisticated algorithms faking normal e-mails, and the spam filters trying to detect them. These e-mails were often intelligible, they could be read and interpreted, but, they didn’t actually have an author. And while they conceivably had a purpose, and perhaps even an intention, that purpose and intent had nothing at all to do with the actual words in the message – the words being used were much more an aesthetic arrangement rather than some sort of communicative act: a forged piece of artwork passing itself off as a masterpiece.

The well known sociologist Irving Goffmann really gave speech act theory its foundation. When Goffman tackles the notion of a speaker, he describes for us the complexity of the idea:

In canonical talk, one of the two participants moves his lips up and down to the accompaniment of his own facial (and sometimes bodily) gesticulations, and words can be heard issuing from the locus of his mouth. His is the sounding box in use, albeit in some actual cases he can share this physical function with a loudspeaker system or a telephone. In short, he is the talking machine, a body engaged in acoustic activity, or, if you will, an individual actor in the role of utterance production. He is functioning as an “animator.” Animator and recipient are part of the same level and mode of analysis, two terms cut from the same cloth, not social roles in the full sense so much as functional nodes in a communication system. (144)

But, of course, when one uses the term “speaker,” one very often beclouds the issue, having additional things in mind, this being one reason why “animator” cannot comfortably be termed a social role, merely an analytical one.

Sometimes one has in mind that there is an “author” of the words that are heard, that is, someone who has selected the sentiments that are being expressed and the words in which they are encoded.

Sometimes one has in mind that a “principal” (in the legalistic sense) is involved, that is, someone whose position is established by the words that are spoken, someone whose beliefs have been told, someone who is committed to what the words say.[20]

Goffmann divided the notion of a speaker into three distinct functions, and these functions are useful in creating a descriptive structure for communicative acts. Several years later, James D. McCawley formulated what has become a classical description of how these roles unfold.[21] In his example, President Ronald Reagan was scheduled to deliver a speech. He explained what he needed to his speechwriter, who then produced his speech. But, due to a scheduling conflict, the president could not deliver the speech, and so he sent then Attorney General Meese to deliver it in his place. In this context, Reagan was the principal, his speechwriter was the author, and Meese became the animator. This example (while simple enough in its own right) illustrates that these three functions can be combined in many ways to create often very elaborate structures.

Standing on the other side of the communicative act is the audience – the hearer or the reader. And of course, we could come up with a very complicated set of potential listeners as well. We function quite differently as listeners when we are eavesdropping on a conversation while waiting in line for movie tickets, or when we are sitting watching stand-up comedy, or attending a political rally, or sitting in the pews in Church on Sunday. I am not going to engage this piece in great detail – because when we deal with texts, we are concerned with very specific sorts of issues about audiences (and I have detailed some of my perspective in my last essay in Interpreter: “Nephi: A Postmodernist Reading”). In particular though, it is important for us to recognize that in the absence of a real audience, when we write, we write to an imagined audience – an idealized audience, which may or may not reflect very closely the real audience that eventually reads what we write. My interest in bringing this notion to this discussion becomes apparent when we look at translation as a communicative act.

Generally speaking, translation is usually not one communicative act, but two. Göran Sonesson tells us:

There is something fairly obvious about translation being a double act of communication. Being at the receiving end, I want to read the new novel by Mo Yan, but I am unable to read Chinese. Therefore, somebody must have read the novel before me, and this must have been a person who can understand Chinese. It must also be a person who can write my language.

This person, then, is at the receiving end of one process of communication, but at the start of another process. What makes this model more useful for understanding translation than earlier models, however, is the ideas about communication as such which I have presented above that the receiver is an active subject, who must concretise the artefact produced by the receiver into a percept; … The translator is a doubly active subject, as interpreter and as creator of a new text. He or she is the receiver of one act of communication and the sender of another one. He or she first has to transform the artefact into an object of his/her own experience. This is a process that cannot be described as encoding, with any intentional depth of the word, because this term suggests a simple exchange of one coded item for another. The correspondence often has to be at a much higher level of understanding.[22]

To put it in less technical terms, the first act of communication is a reading (and interpretation) by the translator, and the second act is a transfer (which is also an interpretation) of what they read into the new language and context in the translation. In other words, in the first communication act, the translator functions as part of the audience. In the second act, the translator participates normally as both the animator and the author functions of the speaker role.

When we apply these roles to Skousen’s models, the first thing to recognize is that Joseph Smith never read the gold plates directly – he didn’t learn the language on them. Joseph Smith is not the person described by Göran Sonesson. Skousen tells us that in the model for loose control, “Ideas were revealed to Joseph Smith”.

This is a second communicative act (the writing of the Gold Plates was the first) in which Joseph Smith is the audience. These ideas are a communicative act that Joseph can understand. But in this model, the three functions of the speaker aren’t given to us. We can assume that the principal remains the same as it was for the gold plates (that is, that the ideas in translation are still representative of the original authors of the gold plates).

Skousen then suggests that Joseph “put those ideas into his own language”. This becomes a third communicative act, and in this act, Joseph has to interpret these ideas, and put them into his own language. So, Joseph Smith functions as both author and animator (and Joseph shares that role of animator with his scribes – and, if we are concerned with the published version of the text of the Book of Mormon, eventually with the copyists and printer).

In the tight control model, Skousen tells us that “Joseph saw specific words written out in English and read them off to the scribe”. Joseph merely repeated what he saw or read. There is no third communicative act described here. We have a principal (just as we did with the loose model). But we do not know who the author is.

That author produced the English words that Joseph reads, and so is also the animator of the text – but in this case, he shared that role of animator with Joseph Smith, with the scribes, and with the copyists and printer.

Earlier, I quoted Goffman who explained that “Animator and recipient are part of the same level and mode of analysis.” There is no third act of communication if Joseph has no interpretive involvement, and does not transform that second communicative act into his own experience. Joseph does not translate here.

Because there is no third act of communication, when we deal with questions of scribal changes, or changes in the copied text prepared for the printer, or changes made during the printing process, what we are really describing is the transmission of the text (and not some sort of translation, or even evidence for translation – these kinds of issues cannot provide us with any information about the translation or the translator). This does bring me back to the idea that we often favor the kinds of tools used in Biblical studies, and those studies have a lot of interest in these sorts of issues in transmission: orthographic variants, errors of various sorts, emendations, and so on – because they are helpful in moving towards an original text. And of course, when we engage these issues, those tools are profoundly helpful – and they can help us move towards the original text. But that text remains the text that Joseph read, and shouldn’t be confused with the original writing on the Gold Plates.

The Audience

In several of these communicative acts, the best defined role is that of audience. And yet, the audience is the most frequently ignored role in our current discussions on translation for the Book of Mormon. We can look around ourselves at a conference like this, and see the very real audience that actually reads the Book of Mormon. But, what about that theoretical audience to whom the book was written by the translator in that last communicative act?

Audiences play a significant role in the way that texts are written (including translations). Perhaps the simplest and potentially most profound way in which this plays out is in the language itself. This is especially true in translation, where the objective is to create a text that can be read by the audience out of a text that cannot. With the Book of Mormon, this is language is English. But, what do we make of this English? I will come back to this question in a couple of minutes, because it is actually a part of the dialogue that we currently see in Book of Mormon studies. The influence of the intended audience doesn’t stop with language – it covers syntax and grammar, it covers imagery and rhetorical figures. Lawrence Venuti wrote that:

A translated text, whether prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction is judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers, and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text – the appearance, in other words, that the translation is not in fact a translation, but the “original.” The illusion of transparency is an effect of fluent discourse, of the translator’s effort to insure easy readability by adhering to current usage, maintaining continuous syntax, fixing a precise meaning. What is so remarkable here is that this illusory effect conceals the humerous conditions under which the translation is made, starting with the translator’s crucial intervention in the foreign text. The more fluent the translation, the more invisible the translator, and, presumably, the more visible the writer or meaning of the foreign text.[23]

But, good translation goes much further than this. Eva Hung tells us that

many of the translation activities which led to new developments and changes in Chinese culture were initiated or undertaken by non-Chinese people. For their work to be effective, they had to have sufficient knowledge of China’s contemporary needs to be able to properly place both themselves and their work within this host culture.[24]

Good translations don’t just re-encode language, they transform it. This was actually noted quite early. Alexander Tytler, wrote in 1791 that:

The translator ought always to figure to himself, in what manner the original author would have expressed himself, if he had written in the language of the translation[25]

When we translate too closely (too literally), Venuti tells us, we risk “obscure diction, awkward constructions, and hybrid forms,” engaging in “translationese”, a word defined in the OED as:

The style of language supposed to be characteristic of (bad) translations; unidiomatic language in a translation; = translatese, translatorese.

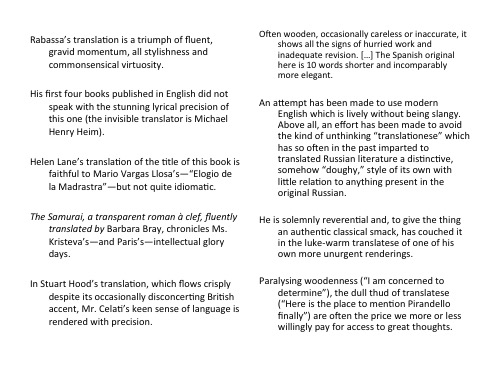

This audience driven view of translation produces some interesting issues when we approach the Book of Mormon. Why? Because by our standards (and even by the standards of that first audience in 1830), the Book of Mormon does not seem to be very fluent. Venuti, referring to a number of reviews of translation that he uses to illustrate what is meant by fluency in a translation tells us that a fluent translation is

written in English that is current (“modern”) instead of archaic, that is widely used instead of specialized (“jargonisation”), and that is standard instead of colloquial (“slangy”). Foreign words (“pidgin”) are avoided, as are Britishisms in American translations and Americanisms in British translations. Fluency also depends on syntax that is not so “faithful” to the foreign text as to be “not quite idiomatic,” that unfolds continuously and easily (not “doughy”) to insure semantic “precision” with some rhythmic definition, a sense of closure (not a “dull thud”). A fluent translation is immediately recognizable and intelligible, “familiarised,” domesticated, not “disconcerting[ly]” foreign, capable of giving the reader unobstructed “access to great thoughts,” to what is “present in the original.[26]

Our two dictation models will approach this issue in very different ways. In his tight model, Carmack suggests that this language – this dialect of English – is used, because this was the language of the translator. And he was doing exactly what Venuti suggests – providing us with a fluent translation of the gold plates. In a recent essay in Interpreter, Carmack suggests:

The linguistic fingerprint of the Book of Mormon, in hundreds of different ways, is Early Modern English. Smith himself — out of a presumed idiosyncratic, quasi-biblical style — would not have translated and could not have translated the text into the form of the earliest text. Had his own language often found its way into the wording of the earliest text, its form would be very different from what we encounter.[27]

This also suggests a very real gap between the idealized audience of the translator and the very real first audience who read it. And this is a conclusion that Carmack embraces – as he notes at the end of his essay:

A large amount of textual evidence — and the foregoing discussion contains only a sliver of it — tells us that Joseph Smith did receive and read a revealed Early Modern English text. Understandably, he may not have been fully aware of it.

At the risk of taking some liberties, this is something like suggesting that while the translation was quite fluent, it simply could not be helped that this translation would not be read for a significant period of time, and that its first readers would not appreciate the fluency of the text – because they did not resemble the audience envisioned by the translator.

By contrast, the loose model suggests that the final translator (Joseph Smith) is preparing a translation for a contemporary audience, and that it simply isn’t a fluent translation. Carmack argues against this notion, suggesting that this lack of fluency is simply a “presumed idiosyncratic, quasi-biblical style” – that the translator was imitating scripture. From another perspective, Gideon Toury (a non-LDS scholar of translation theory) suggested back on 2005 that the Book of Mormon was presented as a translation because it had a greater ability to create cultural change. As he noted:

As has been demonstrated so many times, translations which deviate from sanctioned patterns — which many of them certainly do — are often tolerated by a culture to a much higher extent than equally deviant original compositions.[28]

In other words, had Joseph Smith been the translator, and had he prepared a completely fluent translation, it would have seemed far more likely to his intended audience that it was an original work, and not ancient scripture. I should note that Toury’s study, which relies exclusively on Fawn Brodie for biographical details about Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon, does in fact assume that it was an original work. The point though is that it is also quite possible to see the Book of Mormon’s lack of fluent style as a deliberate part of creating the modern text of the Book of Mormon as a communicative act. In contrast to Carmack’s view, this approach suggests that the archaic language isn’t intended to convey a text written in Early Modern English, but rather, that it intended to incorporate what might be labeled “translationese”. Part of its impact is created when we understand the text as a translation of ancient work, and so this becomes part of the rhetorical strategy of the text in translation. The fluency that Venuti values has been given up to an extent to keep the text from sounding too original, and to help its audience identify the text as scripture.

I want to point out something which I think should be obvious here – this deliberate use of archaic language can be understood in many different ways. It can be understood both in the context of a tight and loose model of dictation. And it can be understood with a wide range of potential translators. What this framework does is help us articulate what role in our communicative act is responsible for the features we see in the text.

Reading Through the Lens of Translation

Not too long ago, I published an essay in Interpreter that spent some time exploring Nephi’s idea of likening scripture unto himself – and the way in which he reinterpreted Isaiah to fit the current context of his people and the society they were trying to build in the New World. This was a translation very much in the modern sense that I have been discussing this morning. And Nephi is quite clear about what he is doing – he tells us (the readers) that his people have a hard time with Isaiah because they do not understand it’s historical context. And that one way to fix this issue is deliberately removed from the equation:

For I, Nephi, have not taught them many things concerning the manner of the Jews; (2 Nephi 25:2).

In this way, Nephi remakes these scriptural texts into something relevant for his people, and often in ways that ignored the original context and intentions of their authors. This provides for us a way of understanding the Book of Mormon as a modern translation – as a modern text. The first readers of the Book of Mormon not only had not been taught about the Nephites, their only real source of information about them was in the text itself. It should not come to us a surprise to find material in the Book of Mormon that has been recontextualized for its intended audience.

And when we find this information in the text, it tends to create something of a gap between the reality we see and our expectations – expectations drawn from our attempts to make the Book of Mormon as much like the Bible as possible. Some of you might be aware of the response to David Bokovoy’s suggestion that the Book of Mormon could be considered at least in part pseudepigraphical. This isn’t an unreasonable conclusion if we adopt the tool kit of biblical studies as our primary approach, and we conflate the modern text of the Book of Mormon with its ancient sources. In a sense, it is perhaps similar to the conclusions we might see from Biblical Studies if they only used the text of the King James Bible, and had no access to archaeological information or original language sources.

When we approach the text of the Book of Mormon, our studies need to be cognizant of the Book of Mormon as a modern text – and as a text that has been recontextualized for a modern audience – a text whose author was potentially aware of the interpretations that would be given to the text, and the implication of those interpretations on issues contemporary with its first readers. Should we be surprised to sometimes find our own questions reflected back at us from its pages?

When we look for chiasmus, we also have to ask how that chiasmus will filter through the potential translation layers we envision. When we see places where the text engages New Testament ideas and values, is this potentially the way that a translator understood the text in the modern context? Is this the way the translator believed that the original author would have expressed himself, if he had written it in English, and in a modern time frame? And when we see text that is nearly identical to the King James, perhaps it is there as a way of helping its first readers identify the biblical passages being referred to, instead of suggesting that they are completely literal translations from the gold plates that just happen to validate the King James translation.

Brigham Young in a sermon delivered in 1862 seemed to recognize a fluidity in context:

When God speaks to the people, he does it in a manner to suit their circumstances and capacities. … Should the Lord Almighty send an angel to rewrite the Bible, it would in many places be very different from what it now is. And I will even venture to say that if the Book of Mormon were now to be rewritten, in many instances it would materially differ from the present translation.

I believe this is even truer today that it was at the end of the 19th century. And I believe that a more nuanced understanding of translation as a process can help us understand how to place Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon as a translation of an ancient text.

[1] This is a draft copy of a presentation prepared for the FairMormon Conference, August 3-4, 2016.

[2] Glen G. Scorgie, “Introduction and Overview” in Glen G. Scorgie, Mark L. Strauss, and Steven M. Voth, eds., The Challenge of Biblical Translation, Zondervan: Grand Rapids, p. 23.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Stephen D. Ricks, “Notes and Communications: Translation of the Book of Mormon: Interpreting the Evidence” in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2/2 (1993): 201–6. http://publications.mi.byu.edu/publications/jbms/2/2/S00014-50aa6550e386814Ricks.pdf

[5] Royal Skousen, “How Joseph Smith Translated the Book of Mormon: Evidence from the Original Manuscript” in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7/1 (1998): 22–31. https://journals.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/JBMRS/article/download/19835/18401

[6] http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/appendix-4-testimony-of-three-witnesses-late-june-1829

[7] http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/preface-to-book-of-mormon-circa-august-1829#!/paperSummary/preface-to-book-of-mormon-circa-august-1829&p=1

[8] The published letter along with a transcript can be found at: http://juvenileinstructor.org/1829-mormon-discovery-brought-to-you-by-guest-erin-jennings/

[9] http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/letter-to-noah-c-saxton-4-january-1833?p=4

[10] This comes from the HC 1:220. The original meeting minutes read: “Br. Joseph Smith jr. said that it was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the book of Mormon, & also said that it was not expedient for him to relate these things &c.” (Conference Meetings, Orange, Ohio, 25 October 1831, in Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, editors, Far West Record [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983], 23.)

[11] In Jeffrey Bradshaw’s recent essay, he quoted some extended comments on this topic from our personal correspondence: http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/now-that-we-have-the-words-of-joseph-smith-how-shall-we-begin-to-understand-them-illustrations-of-selected-challenges-within-the-21-may-1843-discourse-on-2-peter-1/

[12] Stanford Carmack, “Joseph Smith Read the Words” in Interpreter, Vol. 18 (2016), p. 41-2. http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/carmack-v18-2016-pp41-64-PDF.pdf

[13] http://juvenileinstructor.org/1829-mormon-discovery-brought-to-you-by-guest-erin-jennings/

[14] Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?” in BYU Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2004), pp. 103-130. https://ojs.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/BYUStudies/article/view/6935/6584

[15] Ibid., p. 126.

[16] Ibid., p. 104.

[17] Horst Steinke, “Vico’s “Liber metaphysicus”: An Inquiry into its Literary Structure” in Laboratorio dell’ISPF, Vol. XI (2014). http://www.ispf-lab.cnr.it/2014_301.pdf

[18] http://www.academia.edu/8529105/Ring_Composition_Some_Notes_on_a_Particular_Literary_Morphology

[19] Royal Skousen, “How Joseph Smith Translated the Book of Mormon: Evidence from the Original Manuscript” in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7/1 (1998): 22–31. https://journals.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/JBMRS/article/download/19835/18401

[20] Erving Goffmann, Forms of Talk, University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1981, p. 144.

[21] James D. McCawley, “Speech Acts and Goffman’s Participant Roles” in Proceedings of the First Eastern States Conference on Linguistics, Ohio State University: Columbis, 1984, pp. 260-74.

[22] Göran Sonesson, (2014) “Translation as a double act of communication. A perspective from the semiotics of culture.” In Our World: a Kaleidoscopic Semiotic Network. Acts of the 11th World Congress of Semiotics of IASS in Nanjing, October 5 – 9, 2012, Vol. 3. Wang, Yongxiang, & JI, Haihong (eds.), 83-101. Nanjing: Hohai University Press. https://www.academia.edu/3748506/Translation_as_a_double_act_of_communication._A_perspective_from_the_semiotics_of_culture?auto=download

[23] Lawrence Venuti, The Transltor’s Invisibility, Rutledge: New York, 1995, p. 1.

[24] Eva Hung, “Cultural Borderlands in China’s Translation History”, in Translation and Cultural Change, Eva Hung, ed., Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2005, p. 41.

[25] P. 201 Tytler, A.F. (1978) Essay on the Principles of Translation, ed. J.F.Huntsman, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, as cited in Lawrence Venuti, The Transltor’s Invisibility, Rutledge: New York, 1995, p. 70.

[26] Venuti, pp. 4-5.

[27] http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/joseph-smith-read-the-words/#more-8037

[28] Gideon Toury, “Enhancing cultural changes by means of fictitious translations”, in Translation and Cultural Change, Eva Hung, ed., Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2005, p. 4.