Thanks to the Internet, the early summer of 2015 has seen a public exchange about the historicity of the Book of Mormon. The seeds of the controversy are as old as the Book of Mormon itself, but the nature of the arguments have changed. In the earliest years the very fact that the Book of Mormon described civilized inhabitants of the New World was viewed with suspicion at best. Those who believed in the Book of Mormon celebrated books and other reports that supported the idea that there had been cities and higher cultures than those that were more familiar to contemporaries.

With the increasing information about the early inhabitants of the Americas, the discussion about the Book of Mormon often centered on demonstrating that it wasn’t surprising that Joseph Smith would have written a book describing civilized Indians. That argument set the tone for many to come, including the public discussion we have seen this summer. LDS authors propose some type of evidence for the Book of Mormon which is declared to be insufficient because it may be explained in other ways.

This 2015 debate between Philip Jenkins as critic and William J. Hamblin as a defender of the Book of Mormon has also seen the very clear presentation of an argument that has been gaining traction over the last several years. The argument can be encapsulated in one paragraph from Jenkins:

I offer a question. Can anyone cite any single credible fact, object, site, or inscription from the New World that supports any one story found in the Book of Mormon? One sherd of pottery? One tool of bronze or iron? One carved stone? One piece of genetic data? And by credible, I mean drawn from a reputable scholarly study, an academic book or refereed journal.[1]

It was a question reiterated later in the back and forth between Jenkins and Hamblin:

Repeatedly, I have asked for ONE piece of evidence from the Americas, and answer has come there none [sic, intent not clear], for the simple and obvious reason that there is none. There is no other field of academic study in which a situation like this would arise, in which alleged experts would not be able to produce a single fact to support the existence of their boasted field of activity, never mind its value – just its existence.[2]

The ubiquitous and relatively new Internet might make it appear that this is part of a new assault on the Book of Mormon. In fact, it is simply the continuation of the same problem we have seen for ages. Nearly half a century ago, Milton R. Hunter gave a devotional address to students at Brigham Young University. He described some correspondence he had had with members of the church:

I have people write to me and say, “We would like to have you recommend a lot of books to us written by non-Mormons on archaeology and the Book of Mormon which sustain the Book of Mormon.”

I write back and say, “I can’t recommend a lot of books to you written by non-Mormons which sustain the Book of Mormon.

“The archaeologists find archaeological evidences and write their books. Some of us Mormons have gleaned the appropriate evidence from the archaeological books and correlate them with the Book of Mormon to sustain the ancient Nephite records. The non-Mormon, however, hasn’t been interested in doing such a thing and perhaps will not be. Don’t expect him to write a book like that for you. Don’t be so wishful in your thinking—naïve in your thinking—because such doesn’t exist.”

The fact that things are as they are doesn’t make the Book of Mormon untrue nor does it do away with archaeological evidences.[3]

What many Latter-day Saints want is really no different from what Phillip Jenkins wants. Where is that one undeniable piece of evidence? We become sure that it must exist because we know that there is so much evidence for events in the Old World. Surely the Book of Mormon should have exactly the same kind of opportunity for conclusive evidence as does the Bible. Those who suggest that there should be conclusive evidence for the Book of Mormon because there is conclusive evidence for Jerusalem, or Hezekiah’s tunnel, are missing an important difference that those who work in the New World recognize immediately. The two historical contexts are significantly different and the nature of those differences precludes the kind of conclusive evidence that we might have for certain archaeological connections to the Old World.

The first critical difference is the ability to precisely identify sites because there has been a continuous presence on those sites. We have never lost sight of where Jerusalem is. It is absolutely certain that when we dig in modern Jerusalem, we find remains from older strata that we[4]re Jerusalem. Very few New World sites have that advantage. In the Maya area, the most important ruins were abandoned and had no current city or significant population at the time of the Conquest. Their locations were lost to time in many cases, to be revealed only when jungles were peeled back to reveal them. Even for some sites that had older names, the names by which they were known at the time of the Conquest tended to come from the Nahuatl language that was the tongue of the dominant Aztec hegemony. For many Maya sites, the original designation was lost.

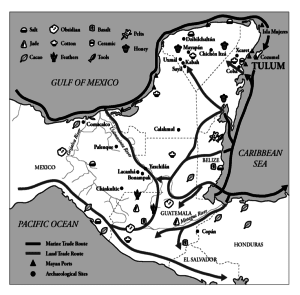

The next critical difference is the availability of documents. The Old World is document rich. Mesoamericanists can at least look to the Maya from some hope, but the Maya are the only culture for which we have readable language from before the Conquest. The rest of the documents ethnohistorians use to reconstruct Mesoamerican history and religion were written in Latin script after the Conquest, and most in Spanish rather than the original language (which some very fortunate exceptions). Even among the Maya, however, writing is not particularly helpful for the Book of Mormon.

The vast majority of the texts that have remained postdate the Book of Mormon. While we might wish that there were a mention of a Nephite name or city in those texts, the chances that anyone wrote about a people who had been gone for a century or two would be slim. That doesn’t mean that no one was writing during Book of Mormon times. The difference is that we have texts on pots and carved stone. Anything on as perishable medium simply didn’t survive (either naturally or by escaping Spanish zealous destruction). The painted murals of the San Bartolo temple confirm that the Maya of the time were writing, but that earlier form of their writing is not yet fully decipherable. Nevertheless, it does tell us that there was writing and that we have probably lost a lot because it dated from times when the Maya painted their texts on stone rather than carve them.

What does that mean for the Book of Mormon? It means that the kinds of evidence that produce conclusive evidence do not exist not because of anything due to the Book of Mormon, but due to the nature of the evidence available in the New World. Let us suppose that we have an unprovenanced painting that lists some kings of a particular city. We might be able to create a case that the list described the king list for that city, and that the list represented the actual kings who had lived there. Is it conclusive proof of the kings or the city? It is evidence, but not conclusive.[5] In that case, it might be acceptable unless there was some other similar pot that contradicted it. Both pots are still evidence, but now even less conclusive.

Olmec is the name given to a cultural trend that is the oldest high civilization in Mesoamerica. It is the result of a late mistaken identification because the ruins were found in the land where the people now designated as Olmeca-Xicalanca lived. The name is surely wrong, but we don’t have a better one. There is conclusive evidence that the people we call Olmec lived. We know a lot about where and when, but there is no indication of what they called themselves or what they called the cities in which they lived. There is no conclusive evidence for the language they spoke. Because the Book of Mormon Jaredites fit into the time period when there were Olmec and are suggested to have lived in the region where there were Olmec, some LDS writers have mistakenly suggested that the Olmec were really Jaredites. I would not make that equivalence, even though I do suggest that Jaredites lived in Olmec culture.

The important point is that we could easily dig up a city and display any number of artifacts. It could be a Jaredite city. However, there cannot be conclusive proof that it was Jaredite because there is nothing to tell us the name they used for themselves. So it is Olmec—even though that name is surely wrong.

The problem with asking for that one piece of evidence is that it is an assumption based on what can be done in the Old World. The lack of conclusive evidence for pretty much anything in the New World is based on the nature of the available nature of evidence in the New World. All archaeology and ethnohistory has precisely the same problem. The difference is that there is a traceable cultural assemblage that we can trace through history to more recent peoples. Therefore, we can link the Classic Maya to the modern Maya even though their whole cultural inheritance was diminished at the time of the Conquest and subsequently extinguished.

The demand for that one piece of evidence assumes that conclusive evidence is possible for that location and time period. It really isn’t. In its absence, we are not left with a void, but with the necessity of building a case rather than relying upon that one piece of conclusive evidence. Both the problem and solution can be seen in the problem of historical linguistics in the New World.

I find that the closest field that must face similar issues is historical linguistics. The field of historical linguistics attempts to move the development of language backwards in history to determine what the language was that led to a current language. Thus historical linguistics looks at the similarities among the various Romance languages and examines how they evolved from Latin. Historical linguistics looks at what the putative Indo-European language might have been like to lead to the many languages now assigned to that family. In the Old World, documents have been able to assist some of this task, but in the New World we are left with the problem of reconstructing a history of language change where little or none of that history was recorded. How do linguists do it? Bruce L. Pearson provides an important description of the method:

Sets of words exhibiting similarities in both form and meaning may be presumed to be cognates, given that the languages involved are assumed to be related. This of course is quite circular. We need a list of cognates to show that languages are related, but we first need to know that the languages are related before we may safely look for cognates. In actual practice, therefore, the hypothesis builds slowly, and there may be a number of false starts along the way. But gradually certain correspondence patterns begin to emerge. These patterns point to unsuspected cognates that reveal additional correspondences until eventually a tightly woven web of interlocking evidence is developed.[6]

I propose that this model tells us just how we should proceed to build a case for the Book of Mormon. We cannot find connections between the Book of Mormon and history unless we look. However, finding something that appears to be a connection does not mean that there was one. Once we have the possibility of a connection, we have to return to the problem and begin to work out more connections. In linguistics, it is not sufficient to accept simple similarities. Linguists look at sound changes and when there are logical sound changes that explain how one language relates to another, the probabilities of a similar parent language increase. The larger the number of these cognate sets that can be set into a common set of sound shifts that explain how the daughter languages evolved from the parent language, the more certain the connection between the daughter languages and the reconstructed parent.

What would be the response of a Phillip Jenkins if he were to ask a historical linguist for the one piece of conclusive evidence that demonstrates that Mixe-Zoque was the language of the Olmec (and that is the current best hypothesis)? In the case of historical linguistics it is a nonsense question. There isn’t one and cannot be one because of the nature of the evidence. The evidence for Book of Mormon historicity similarly requires complex iterative development of evidence. The nature of the problem in the New World makes asking for that one conclusive piece of evidence directly parallel to asking for conclusive evidence that the Olmec (whatever they called themselves) spoke Mixe-Zoque (itself a constructed language known only through historical linguistics).

Building the Web of Interlocking Evidence

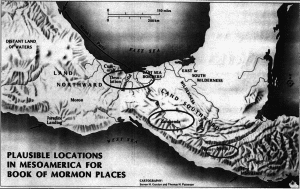

The beginning of a study in historical linguistics starts with a basic comparison. In the case of the Book of Mormon, the most elementary correlation is that of geography. Unless we can present a case that a proposed location might be the geography described in the Book of Mormon, there is no reason to look further. Even geography requires an iterative process if it is to become an important cornerstone for the web of interlocking evidence. With the basic outlines of a geography, further details must be fit including elevation, hydrology, and climate. With those in place, ever more important correlations might be made if the events described for 3 Nephi can have an explanation based on that geography.

That beginning has been done and the most tightly interwoven set of characteristics would place the events of the Book of Mormon in the more southerly portions of the region described as Mesoamerica. Having a place means that it is now possible to begin to look at other types of data. John L. Sorenson has also done that, making broad comparisons of cultural traits found in Mesoamerica to the information in the Book of Mormon.

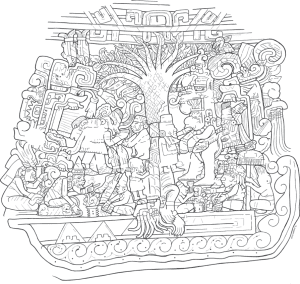

What I am suggesting is that we need to move that type of comparison to the next level of iterative analysis. Pearson noted that while developing an argument for the relationship between two or more languages that there are likely to be false starts. We can expect no different as we examine New World history against the Book of Mormon. What is required is the same thing that is required of historical linguistics. When we discover a false start, we remove those pseudo-cognates and continue refining the models. Perhaps the most well-known false starts in placing the Book of Mormon in the real world are the stela known as the Tree of Life stone and the story of the Mesoamerican great white god, Quetzalcoatl.

M. Wells Jakeman interpreted Izapa Stela 5 as not only a tree of life, but as a detailed representation of the Lehi’s dream of the tree of life. The possibility of a tangible artifact specifically related to the Book of Mormon fired the imagination of the general LDS community. Hanging on my wall is a small plaster rendition of Izapa Stela 5 that I believe was produced by a Southern California Relief Society. In spite of the continuing popularity of what has also been called the Lehi Stone, Hugh Nibley argued against Jakeman’s correlations.[7] As better drawings of the eroded stela have become available, and as the scenes on the stela are compared to other scenes from the same site, it has become apparent that Jakeman’s reading was based on an inaccurate rendition of the drawing, a misapplication of Central Mexican naming conventions from the codices to this early stone from a different culture, and a failure to compare scenes in the stone to the other stelae in the area.

In spite of the strong evidence that Stela 5 has nothing to do with the Book of Mormon, the LDS community has been very slow to abandon this favorite piece of evidence. Nevertheless, if we are to build a strong web of interlocking evidence, incorrect correspondences such as the claim that Izapa Stela 5 represents Lehi’s dream must be set aside. That is an important part of the process of the iterative building of the case. Sometimes the correspondences get better. Sometimes they fall apart entirely.

The second popular proof of the Book of Mormon that we must set aside is the idea that there is anything in the Quetzalcoatl legends that is a remembrance of the Book of Mormon. I began my personal campaign change opinions about this material in 1986.[8] Unfortunately, that information has become much more popular in non-Mormon and even anti-Mormon circles than among members. The LDS myth about the myth appears to almost as strong as it ever was. Even John L. Sorenson’s recent Mormon’s Codex perpetuates the idea that Quetzalcoatl encodes some correlation to the story told in 3 Nephi.[9]

The material surrounding Quetzalcoatl is quite complicated. The good thing is that we have as much or more material about Quetzalcoatl than any other Mesoamerican deity. The bad news is that we have so much information that most LDS writers to promote Quetzalcoatl as a remembrance of Jesus Christ haven’t read it all. There is a large body of early Spanish literature suggesting that Quetzalcoatl was a remembrance of St. Thomas who had preached to the Central Mexicans. LDS writers have concentrated on that literature and borrowed almost all of its evidence while shifting the identification of the mysterious preacher to Jesus Christ. Unfortunately, the early Spanish writers had already misinterpreted the Central Mexican legends in order to make them appear to support the St. Thomas hypothesis. We can tell this because there are some documents that tell parts of the Quetzalcoatl legend that are recorded in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. For example, an important very early document records this scene from Quetzalcoatl’s life:

His uncles were greatly angered, and shortly they left, going before Apanecatl who came out quickly. Ce Acatl [another name for Quetzalcoatl] rose and split open [Apanecatl’s] head with a smooth and deep cut, from which blow he fell to the ground below. Immediately [Quetzalcoatl] caught hold of Solton and Cuilton. The beasts blew on the fire and presently he killed them. They gathered them together, cut a little of their flesh, and after torturing them, they cut open their chests.[10]

We never see that story in the various arguments linking Quetzalcoatl and Jesus Christ. Perhaps it is only a corruption of the tale—except that when all of the stories are gathered we can see how the Spanish writers made their subtle changes so that what really was a very Mesoamerican deity began to appear foreign.

The issues with the ways that LDS authors have used both Izapa Stela 5 and the Quetzalcoatl material tells us that as we work toward more precision in our correlations between history and the Book of Mormon that there are times when we will find that we have wandered down a few dead end streets. That certainly does not mean that we haven’t been able to shine even more light on and broaden some of the roads that we had previously examined.

Embedded in the concept of history is the passage of time. Historians certainly understand that events occur in time, and that the times in which the events occur sometimes influence, but are more often influenced by the greater flow of culture and history surrounding them. For the Book of Mormon, history has not left any clear events where the Book of Mormon altered the discernible flow of history in either the Old or the New World. What the Book of Mormon does show is its own participation in and influence from the greater trends in the lands where it occurred. We begin to see these webs of interlocking evidence when we look at what the Book of Mormon says in the context of particular times. There are a number of ways that the Book of Mormon fits into very specific times and places. I will note three of those.

The People Want a King

Not long after Nephi separated from his brothers, he formed a new community. He reported: “And it came to pass that they would that I should be their king. But I, Nephi, was desirous that they should have no king; nevertheless, I did for them according to that which was in my power” (2 Ne. 5:18). Nephi didn’t explain his reluctance to accept the kingship, but it is important to our understanding of the historical context that becoming king was not his idea. Nephi was made king because his people wanted it enough to overcome Nephi’s objections. That raises the important question of why.

The answer is possible if we connect the dots between time and place. Beginning with the Mesoamerican location and adding the timeframe of the early Nephite community, we can look at what is known of the surrounding region. It is a time when that area was involved in a wide regional movement away from smaller communities and into cities with kings.

I suggest that the desire for a king reflected a surge in the rise of kings all around the city of Nephi. An interesting study is Cerros, a city located on the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, dating to the Preclassic. This village was transformed into a city center complete with monumental architecture. That transition from village to city, from simple architecture to monumental and symbolic architecture, suggests that there was also a shift in the government of the village. Villages typically have headmen as rulers. The symbolism of the architecture after the transformation suggests that they moved from that simpler form of government to a Mesoamerican-style king around 300 b.c. David Drew summarizes the “speculative reconstruction” of the archaeologists who investigated the site:

They suggest that its inhabitants deliberately chose to adopt the institution of rulership. They did so because they were forced to confront the reality of developing social inequality within their society. Instead of allowing this to lead to conflict, to the break-up of social fabric, they sought not to deny such inequality but to embrace it, to institutionalize it by creating one central force so powerful and given such extraordinary symbolic legitimacy that it overrode all others. What is suggested here is a kind of social contract of rights and obligations. Humbler members of the community had to pay tribute to maintain the ruler and his lineage or followers, to participate in the building of temples and other communal construction. But in return the ruler provided security, managerial authority to resolve disputes and organize public works and above all, as we have seen, he provided a religious focus—he took care of the spiritual matters of so fundamental an importance to such a society.[11]

David Webster describes the cultural development of this general time period:

Prior to about 650 b.c. we can detect no signs of particular social or political complexity in the archaeological remains of these early settlers, although obsidian and other objects imported from Highland to Lowlands show that scattered populations were by no means isolated from one another. During the next two centuries a few communities in the central Maya Lowlands and Belize began to build masonry civic structures 10–14 m (33–46 ft.) high, some with stucco masks and other decorative elements that have a generic resemblance to those found at later Classic period sites. About the same time even bigger structures were erected in the valleys of El Salvador. Boulder sculptures there, and also along the Pacific coast of Guatemala and Mexico, show sophisticated symbolic motifs that possibly reflect influences from the Olmec culture of the Mexican Gulf Coast. At various highland centers elaborate burials, large buildings, stone stelae, and what might be early glyphs and numerals all appear by about 400 b.c. Some archaeologists believe that the basic ideological and iconographic conventions of kingship originated in highland centers such as Kaminaljuyú (where Guatemala City is now located).[12]

The Book of Mormon places Nephi’s kingship in the right location for the nascent Mesoamerican forms of kingship, albeit early in its development.[13] Seeing Nephite kingship early should not be taken as evidence that it triggered Mesoamerican kingship (especially since the reverse is the more likely scenario). In the city of Nephi we see evidence of the general trend to kingship that would continue in other Mesoamerican communities. Although it appears early, it is probably only because we have the textual information for its beginning rather than being required to wait for the monumental architecture that provides the archaeological evidence for kingship.[14]

Mosiah1 Flees the City of Nephi

The loss of the 116 pages of the translation of Mormon’s opus almost lost all of the introduction to Mosiah1 of the city of Nephi. We know little about him, save that somewhere before 200 b.c. he was commanded to flee the city of Nephi. Like Nephi before him he was to take “as many as would hearken unto the voice of the Lord” (Omni 1:12; see also 2 Ne. 5:5). Perhaps the lost text explicitly described why he had to flee, but our current text does not tell us. However, placing in a particular location at a particular time gives us a very plausible reason that he and those who were faithful had to flee the land.

It is plausible that Mosiah1 and his people fled from a military invasion. Around 200 b.c., there was a massive incursion of people into highland Guatemala (Sorenson’s Land of Nephi) from the northwest. They were likely Quichéan peoples. Julia Guernsey indicates that these Quichéans “appear to have moved south and eventually invaded such places as La Lagunita and Kaminaljuyú. They displaced much of the local population and replaced the elites, which, in the case of Kaminaljuyú, were likely Cholan speakers. The displaced inhabitants of Kaminaljuyú fled the area with the arrival of [these] people.”[15] Both Quichéan and Cholan are different Mayan language groups, as Spanish and French are both Romance languages. Without written records we cannot provide precise dates, but it appears that right when the Book of Mormon tells us that Mosiah1 and those who would follow him lefty the city of Nephi, secular history tells us of an invasion that also resulted in the flight of those who lived in that area. If Sorenson is correct in associating Kaminaljuyu with the city of Nephi, that is one of the specific places mentioned from which the exodus occurred.

The Destruction of the Nephites as a People

By the time Mormon is writing, nearly a thousand years of Nephite history have passed. One of the constants in that history is conflict with the Lamanites. Skirmishes and outright wars have been the hallmarks of most of the years for which we have records. During that time the Nephites have won battles and wars, lost battles and wars, and remained as a people to wait for the next conflict with the Lamanites. We know that this cycle of warfare finally ended around a.d. 400 with the destruction of the Nephite people at the Hill Cumorah. After surviving Lamanite wars, including the massive war described in Alma and part of Helaman, why did the Nephites finally succumb, and why at that time? Why not earlier, why not later? The plausible answer comes again from the intersection of time and place.

To set the scene, we begin with Mormon’s observation that “The whole face of the land had become covered with buildings, and the people were as numerous almost, as it were the sand of the sea” (Mormon 1:7). The archaeological record for Early Classic Mesoamerica agrees that there were increasing numbers of people in the Maya world along with an increasing number of new cities. Archaeologist John Henderson notes:

Several regions experienced intensified population growth. Well-developed hierarchies of communities—from tiny hamlets and villages with no indications of special political functions to large cities with all the trappings of centralized power—appeared. Many cities enjoyed a boom in building, especially in civic architecture. Some cities sought and acquired power beyond their immediate hinterlands, and regional states emerged. Marriage, alliance, and warfare variously characterized relationships among autonomous states. Relationships with distant societies also intensified, as the great central Mexican city of Teotihuacan established a long-term presence in the Maya world, especially at Kaminaljuyú in the highlands.[16]

Future Mesoamerican populations would be still larger, but Mormon was seeing the densest population known in any record available to him. Mormon’s tale begins in the way that we have learned to expect. War with Lamanites. Just as typically, it begins with the defeat of the Lamanites (Mormon 1:10–12). While there would be some victories after this time, this was the last true victory. Mormon describes the next war as one that they spent most of their time losing. They not only lost the war, they lost themselves as a people.

At this point in Mesoamerican history, the ties between Teotihuacan in Central Mexico and the Maya civilizations to the south of the Nephite holdings were stronger than ever before. This increased Teotihuacano presence in the Maya heartlands gave both the Maya and Teotihuacan a strong motive to secure the trade route that ran along Nephite territory. As Ross Hassig explains:

Generally, foreign Teotihuacan sites were located in resource-rich areas at great distances from the Valley of Mexico. Teotihuacan did not expand out uniformly, nor did it dominate all adjacent regions….

Perhaps the most famous Teotihuacan-influenced center is Kaminaljuyu, located in highland Guatemala City. People from Teotihuacan apparently dominated Kaminaljuyu from a.d. 400 to 650–700, with at least part of their presence being tied to the greatly expanded exploitation of major obsidian sources during this period. Teotihuacan’s interest was not simply in Kaminaljuyu, but in controlling the goods flowing through its existing trading network. . . . Empires control distant markets by maintaining exclusive rights to trade there, denying access to others, so that, limited to a single trading partner, colonial trade is inherently unequal, working to the advantage of the empire.[17]

The desire for control of the Maya markets may have finally reached the point that a war of destruction became cost-effective. Charles W. Golden suggests: “All-out destruction of the enemy may be expensive in the short term but reduces the need for warfare in the long term by eliminating threats to royal power.”[18]

James N. Ambrosino Traci Ardren, and Travis W. Stanton provide an example from later in time and a different location that nevertheless demonstrates a people who are subjected to multiple military campaigns followed by a final campaign of destruction:

Yaxuná appears to have been located in a hotly contested strategic area in the center of the peninsula. All the previously described conflicts may have erupted over control of this location. Chichén Itzá, also existing within the center of the peninsula a mere 22 kilometers away, would have had no reason to control the nearby site of Yaxuná. From a simple standpoint of cost efficiency, annihilation rather than occupation may have been the preferable option. Additionally, we have suggested that previous wars at Yaxuná represented conflicts between local groups who were backed by foreign patrons or allies. We suggest that the victor of the fourth war was an entirely foreign group from Chichén Itzá who had no vested interest in the government of Yaxuná. Essentially, the Terminal Classic showdown at Yaxuná was not a dynastic struggle at all; it was a war for economic and political control of the entire Yucatán peninsula.[19]

In light of the Yaxuná case, it is significant that Mormon notes a change in the Lamanite army due to the reappearance of the Gadianton robbers. The Gadianton robbers are Mormon’s shorthand for various groups outside of the typical Nephites and Lamanites. They are harbingers of the destruction of nations. The Gadiantons of Mormon’s time are associated with invaders from the north.[20] He tells us that: “And these Gadianton robbers, who were among the Lamanites, did infest the land. . . . And it came to pass that there were sorceries, and witchcrafts, and magics” (Mormon 1:18–19). These are reasonable descriptions of the incursion of Teotihuacan (the principal city in Central Mexico) into the area. Teotihuacan had dominated Tikal by a.d. 378, when their “entrance” to the city is noted on a stela. Their influence in the region became pervasive after that time.

As Hassig explains, one of the ways Teotihuacan could maintain its interests was through the exercise of military might:

A major key to the functioning of hegemonic versus territorial empires is their relative reliance on force versus power. Force is direct physical action—typically military might—that is depleted as it is used. Power is not necessarily force, operates indirectly, and is not consumed in use because it is psychological, the perception of the possessor’s ability to achieve its end. The ability to wield force is a necessary element of power, although a single demonstration, rather than its continued application, may be sufficient to compel compliance.[21]

Teotihuacan is in the Central Basin of Mexico. Tikal is in the Maya lowlands, some 800 miles away along modern roads. Between those two major powers were the Nephites, by this time somewhere around the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and therefore potentially controlling trade routes between north and south. Perhaps that was not to be tolerated. With increase in trade occasioned by the increased presence of Central Mexican goods and ideas among the Maya, it is reasonable to assume that the traditional trade route between Central Mexico and the large Maya centers—a route that necessarily passed through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—had become even more important. At this point in time, and not earlier, there was sufficient reason to make the cost of eliminating the Nephites worth the expenditure.

The Teotihuacano presence among the Maya had strong militaristic overtones, even if the evidence for direct conquest is circumstantial. William and Barbara Fash note:

The settlement pattern data, ceramics, and green obsidian lead us to speculate that a faction with ties to Teotihuacan established itself on the fortress-like hill of Cerro de las Mesas, and unified the diverse competing noble lines, moreover establishing a royal center in a thoroughly indefensible place, in the center of the Copán Valley Bottomlands. David Webster’s hypothesis that warfare was critical in the formation of Maya kingdoms would seem to have much in its favor in the case of the Classic period Copán dynasty. What better way to resolve an internal conflict than to place themselves in the hands of a veteran warrior-merchant, who validated his right to rule by his mercantile and militaristic connections with the mighty Teotihuacan? The skeletal evidence that the man in the Hunal tomb had a parry fracture on his right forearm is interpreted by Jane Buikstra as evidence for a battle wound. As Sharer notes, it is also illuminating when we discuss archaeological confirmation of the pictorial record, since K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ is portrayed with a small rectangular shield on his right arm. . . . Finally it is significant that the strontium analysis of the bones of this individual indicate that he was, in fact, not a native of the Copán Valley, adding important evidence in favor of his having been a “Lord of the West” [a Maya reference to one from Teotihuacan].[22]

The net effect, however, was a change in the nature of politics and artistic representations.[23] Whether solely based on improved weaponry or combined with other tactics, the evidence suggests that the Teotihuacanos were typically victorious over their Maya opponents (based on the widespread presence of Teotihuacano symbols among the Maya during this time period).

Teotihuacano influence would have been immediately visible on the battlefield. Even before the rain of darts from the powerful atlatls, the military “uniforms” of the Teotihuacanos would have been visible.[24] Archaeologist Michael D. Coe describes the typical Teotihuacano military attire: “Teotihuacan fighting men were armed with atlatl-propelled darts and rectangular shields, and bore round, decorated, pyrite mosaic mirrors on their backs; with their eyes sometimes partially hidden by white shell ‘goggles,’ and their feather headdresses, they must have been terrifying figures to their opponents.”[25]

Perhaps this visual indication of the presence of what must have been a known and foreboding enemy explains the Nephites’ original reaction to this new war: “Therefore it came to pass that in my sixteenth year I did go forth at the head of an army of the Nephites, against the Lamanites; therefore three hundred and twenty and six years had passed away. And it came to pass that in the three hundred and twenty and seventh year the Lamanites did come upon us with exceedingly great power, insomuch that they did frighten my armies; therefore they would not fight, and they began to retreat towards the north countries” (Mormon 2:2–3). The Nephite flight described in verse 3 may not represent cowardice but rather a strategic retreat to understand and better prepare for this new type of enemy–an enemy with a more terrible reputation that any the Nephites had previously faced.

Historicity and the Book of Mormon

It would be nice, but less conclusive than many suspect, if there were a single piece of archaeological evidence that would provide the smoking gun demonstrating the historicity of the Book of Mormon. Even if we had that one piece of evidence, it is likely that most would find issues with it and either deny that it was a gun, or that it had ever been fired. Single pieces of evidence are ultimately unsatisfying. Much stronger is the web of interlocking evidence that links together a geography, a specific time, and specific events. The best correspondences between the Book of Mormon and the known history of Mesoamerica are those occasions when place, time, and events all correspond, showing why the Book of Mormon descriptions would not have been accurate earlier or later. Getting an event at the right time in the right place is a single piece of interlocking evidence. Linking larger numbers of those interlocking events makes the cumulative evidence much more significant that pure change. When the overall historical structure is built of those events that match time and space, we can begin to fill out other details that fit the culture area, but which are not necessarily time specific. Certain traits in the Book of Mormon can then be seen to reflect the surrounding culture. The most important are those that productively explain the text in ways that we cannot without the background that a physical location and temporal cultural backdrop can provide.

Continued work carefully examining the ways in which the Book of Mormon corresponds to a Mesoamerican location during the specific times mentioned in the Book of Mormon will continue to develop that web of interlocking evidence that allows linguists to confidently declare relationships between two languages. Just as linguistics must begin with the observation and move to an even closer examination of the evidence for more examples, so too we continue to mine the Book of Mormon and the increasing information about Mesoamerica to see the correspondences. When linguists believe they have two related languages, they then move onto to looking at the phonetic rules that describe how sounds have shifted from one language to the other. In Book of Mormon studies we are required to increase our level of care and precision in the nature of the correlations we make. That means that sometimes we have to admit when we were wrong and forsake popular evidences such as the Tree of Life and Quetzalcoatl as we move to correspondences that can withstand more detailed scrutiny.

There is currently a remarkable set of correspondences that are quite precise for time, place, and event—showing that the Book of Mormon accurately reflects the greater world in which it was written. There may not be that one conclusive evidence for Book of Mormon historicity, but there is a solid web of interlocking evidence that points to a text authentic to a specific place at specific times.

Q&A

Q1: What are the reasons you dismiss the mid-America theory of the Book of Mormon?

A1: We don’t have enough time to go through all of that. Let me give you just a couple of quick ones. The things that look really good about the Central American United States, Mississippian area in the Book of Mormon is that those dates seem to line up and you can get a Jaredite date and you can get a Nephite date. The problem is even though the dates work, the geopolitical differences do not, because you remember that the Book of Mormon says that we have to have Jaredites that aren’t anywhere near Nephite lands until about 200 A.D. The problem is the Adena who are of the Jaredite age were in all of the Hopewell sites and they were the precursors of the Hopewell and so the geopolitical things just don’t match. So you get some really interesting stuff, but nothing actually fits when you really dive down. It’s sort of the kind of problem you have when I was looking at Quetzalcoatl, there’s a lot of stuff that looks like it might fit but when you get into the details, you say oh, that wasn’t as good as what I thought. And that’s kind of what happens with that one.

Q2a: I’m wondering if Gardner would ask the audience by a show of hands [we’ll have to see what this says to see]. Did I shock anyone with things that you thought were true like the tree of life stone? How many of you had thought that the tree of life stone was good and now you’re sad?

A2a: Good the sad hands went down. I don’t want the sad.

Q2b: And they’re asking how do I reconcile the fact that somebody might be sad about that.

A2b: Sigh. Please don’t be sad about good scholarship.

Q3a: I find it interesting that only a handful of the New World cultures appear to be literate.

A3a: Certainly that is correct and all of them that we know about are in the Mesoamerican area.

Q3b: How was it that literacy did not spread more widely either from the Maya or Book of Mormon people?

A3b: I can’t tell you exactly from the Book of Mormon people, because I don’t know. I don’t know of anybody that has actually said why the Maya language and the glyphic system didn’t work so, I will now tell you. And there are no papers on this and this is totally my opinion and if you say that I said it, I’ll probably tell you that I didn’t say it. The Maya glyphic system is set of syllables and they will use the syllables and the sign for each of the syllables and what will happen to create a word is you’ll begin with the central glyph and you’ll have some affixes or something and that will allow you to pronounce the word and it works because Maya has relatively short words that have a consonant vowel construction. So if you’re basically consonant-vowel, consonant-vowel and you’ve only got a maximum of three syllables, you can pack that. When I was doing my Mesoamerican studies, I was working with Nahuatl. Nahuatl…you saw the word Quetzalcoatl right? That’s more than two syllables and they do that all of the time. I suspect that they looked at them and said if I did that I’d have, you know, one thing like this for a word and we just couldn’t figure out how to write it. I suspect that the problem of the language itself didn’t match with the writing system. It wasn’t as flexible as the Roman system we use.

Q4: In creating your Book of Mormon Commentary you said online that you didn’t want to repeat what someone decried in the Millett and McConkie method for their commentary. How do you study the Book of Mormon and not use the revelations to understand its teachings and why shouldn’t you?

A4: Slight misunderstanding I think of what that particular issue is. When I wrote the commentary, I was trying to do something that was more on a scholarly level but I did want to talk about the religious things but I wanted to do it in the context of how Nephites believed. So I’ve got a section in there where I talk about the whole issue of the Mother of God rather than Mother of the Son of God and talk about it from the Nephite context. Many commentaries are devotional commentaries that tell us how to read the Book of Mormon according to what we currently believe. That’s fine. That’s ok. There are many people that really need that level of assistance in what they’re doing and those are the ones that are going to get something out of that. If you’re looking for something else then you have to go to a different location and that’s where the difference lies. I really don’t see too many incorrect ways of reading the Book of Mormon. There’s just a myriad of ways and when you find the one that helps you and gives you the best grounding in it then that’s the one that’s right for you.

Q5: Should we be concerned for your safety and well-being when you said Quetzalcoatl is close to my heart? We don’t want human sacrifice at the conference.

A5: Well according to the Spanish Fathers he did not condone it except for the one that said he shot his brothers.

Q6: If you could say one thing to Phillip Jenkins, what would you say?

A6: If you remember, the thing that I would say is you can’t say one thing. No matter what happens, because when you say one thing, anybody can find a way around it. You look at the one spot on the dog and it’s not going to help you. So you have to change the conversation. Anytime you allow someone to dictate the conversation about the Book of Mormon, to show me a proof, you’ve already lost the conversation because that’s not what we’re going to be able to do. What we’re going to be able to do is show them that it has historicity because it fits into history. But they have to actually do some work, there’s no pabulum here. They’ve got to spend the time and Jenkins clearly isn’t interested in doing that.

Q7: This one’s from a quote from Pedro De Cieza De León who is a Spanish soldier writing about the Inca. They say that out of the regions of the South there came and appeared among them a white man large in stature whose air and person aroused great respect.

A7: Which is one of the reasons why people have been really excited about the Great White God because we get it in so many cultures. What’s really fascinating about that is that you get it in cultures that…you get it at least first in all the Spanish cultures and what clearly seems to happen is that in all of the Spanish texts it takes the same form. Unfortunately in South America we don’t have the literature to dig behind it to see what the texts were. What we can see is that the way it’s being described in Cieza De León is that it’s the same kind of ways we get in Diego de Riano, Torquemada, and some of the others. It makes it highly suspicious that the same culture is repeating the same thing. It seems to be a really good way of making your conquest of the natives fit. You can say, by the way, some white guy came here, therefore we’re white and therefore we’re ok to conquer you because this white guy said we could. It’s a very interesting political thing and it is so widespread because it fit what the conquerors wanted to do. I don’t see any real evidence for it.

Q8: How do we know about early American culture, economic kingship, etc., struggles, and changes if there aren’t many surviving texts?

A8: Really good question! In the New World one of the things that we have to do is take some of the later material and we have to see how well it goes backward in time. So [in] a lot of cases we’re taking more detailed information from later and then trying to find out how to push it earlier. The trick there is that you can’t simply assume that it goes earlier, you have to find some connections so usually you’ll find connections to other iconographic representations where in the earlier one you could say there’s no text that will give this concept or context but we see the same thing later where there is a context and it looks like those two are the same. And then you start getting more of those again, that iterative process, you start learning more about what was happening. Some of the other kinds of things you learn just from archaeology. If you’re looking for the origin of kingship, you’re looking at the development of cultures, monumental buildings, the trappings of the king and so you can see those archaeologically. So there’s a lot of information that you start using. Anybody who works in the New World gets quite imaginative in the way that we have to use data because we just don’t have as much. That doesn’t mean they’re all wrong, it just means we’re subject to correction when we get better data.

Q9: Did the Mulekites travel to the new land by coming across the Atlantic Ocean since they landed on the Atlantic side?

A9: I believe so and the only reason I can say so is because in order for things to work out and for them to land somewhere at a river and move up the river, you’ve got to land on a coast. To get them up there you’re going to be landing in the Gulf of Mexico so it’s suppositions that are built on other suppositions.

Q10: So do you believe that there could be no connections between the legends of the Great White God and Jesus Christ?

A10: As clearly as I can–no connection whatsoever. Now, there are lots of things that I will back that up. And I have people on the Internet who have said you must not have read all of the texts. No more comment on that one.

Q11: What do you think of the so-called Book of Mormon connections with the Popol Vuh?

A11: Popol Vuh is quite late. I don’t know that there are any direct connections. There are certain things about the way they talk about the creation of the earth that look quite Christian. I’m probably more conservative than many on that one. Particularly since when they’re talking about that it specifically says we’re writing about this during Christianity. I think others would say that there are more there and I’m kind of agnostic on that one. Open to argument.

Q12: Do the parallelistic patterns used by Book of Mormon writers reveal rhetorical and logical techniques of the Nephite literate class?

A12: I believe that, yes, even though I don’t think we have a word for word translation. I think that in the translation process we do get structure coming through. So I think they were people who used literary parallels. I believe that they did use chiasm. I believe it is also quite fascinating that other cultures in that area not related, that we know of, to the Book of Mormon, similarly used those kinds of couplets and chiasms. So it was something that I do believe is there in the Book of Mormon. I think it represents Nephite literacy. We also see it in other cultures. I would back away from saying the Nephites taught them that. I think it’s pretty easy to know how to make two parallel lines, so I think that concept was there, but it is quite interesting that those literary techniques are in that area.

Q13: What’s your opinion about the Baja Peninsula being the land of Lehi and Nephi?

A13: As I said, you can pretty much throw pins at a map and you can find something that you think works. The problem is you’ve got to get people there at the right time, they’ve got to be in the right relationship, and then the more you delve into it, the more you want those interconnections and we just don’t find them. You might be able to create a geography in Baja. It’s harder to invent culture there. They just didn’t have it.

Q14: The codices of Mexico written by Lamanites?

A14: Considering that the Nephites said that anyone who wasn’t a Nephite was a Lamanite, sure. They’re almost a thousand years too late to have anything to do with the Book of Mormon so Lamanite sort of in terminology but not in content.

Q15: Where is the Hill Cumorah? Could you talk about some topics surrounding this?

[Shoot. Let me give you the next one and I’ll go back to that.]

Q16: What’s your opinion of Grant Hardy’s edition?

A16: Wonderful. Please read it, it’s a good way to understand the text. I think one of the things we don’t do is read it closer to the way it was dictated. Unfortunately, I think when Orson Pratt made our chapter divisions, he did us a disservice. I think you ought to read it in the original chapter divisions.

A15: Ok. Hill Cumorah. [Do you want me done? Do you me want to answer? Answer this question.] There is a hill in New York that is called Cumorah. It does not fit any of the requirements for the Book of Mormon Hill Cumorah. It is not a good defensive position, it has no archaeology that supports any of the events of the Book of Mormon, any people being there during Book of Mormon times. It’s a clean hill. There’s just nothing there. There is absolutely no evidence that it had anything to do with the Book of Mormon. So there’s a Hill Cumorah, it would be somewhere down in Mesoamerica. Where? We still don’t know that. There are a couple of suppositions. The Cerro Vigia hill is what David Palmer came up with; Larry Paulson has another suggestion that he thinks fits the description better. We don’t have anything that will firm that up other than it will be down there. The last thing to remember though about the Hill Cumorah–we call the New York Hill “Cumorah” because the plates came out of the hill. And we all know that Mormon said, “I hid the plates in the Hill Cumorah.” Well, we all forget that when we say that we know that Mormon hid the plates in the Hill Cumorah, is that Mormon said, “And I hid all these plates in the Hill Cumorah save these plates I’m giving to my son Moroni.” So according to Mormon, the plates Joseph received were never in Cumorah. So the Hill in New York got it name because someone kind of misread the history and gave us an attribution that was incorrect and unfortunately it has stuck with us for a long time.

Scott Gordon: Thank you very much.

[Transcriber’s note: This question and answer session has been lightly edited for clarity.]

Notes

[1] Phillip Jenkins, “Mormons and New World History,” The Anxious Bench, May 17, 2015. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2015/05/mormons-and-new-world-history/ (accessed July 2015).

[2] Phillip Jenkins, as reported in William J. Hamblin’s blog Enigmatic Mirror, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/enigmaticmirror/2015/06/26/jenkins-rejoinder-9-hes-back/ (accessed July 2015).

[3] Milton R. Hunter, “Archaeology and the Book of Mormon,” Summer Devotional Address, Brigham Young University July 19, 1966, 5-6.

[4] It is now expected that the later Maya sites may have names encoded in the glyphic texts. These all postdate the Book of Mormon, and most are not in the area most probable for the Book of Mormon to have taken place.

[5] The National Geographic special, “Dawn of the Maya” originally shown in 2004 has a scene with just this scenario. Dr. Richard Hansen of the University of Utah shows a pot with what appears to be a king list that might associated with El Mirador. However, archaeologists have been unable to find corroboration at the site that the king list really is for El Mirador.

[6] Bruce L. Pearson, Introduction to Linguistic Concepts, 51.

[7] Steward W. Brewer, ”The History of an Idea. The Scene on Stela 5 from Izapa, Mexico, as a Representation of Lehi’s Vision of the Tree of Life,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 8:1 (1999): 17-18.

[8] Brant A. Gardner, “The Christianization of Quetzalcoatl,” Sunstone 10, 11 (1989): 6-10.

[9] John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013),

[10] “Leyenda de los Soles,” in Codice Chmalpopoca, translated by Primo Feliciano Velázquez (Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónima de México, 1975), 125. Translation mine.

[11] David Drew, The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings, 139.

[12] David Webster, The Fall of the Ancient Maya, 44.

[13] The movement from chiefdoms to states is typically traced to around 300 b.c. Evans, Ancient Mexico and Central America, 205–6. That designation refers to social complexity rather than the institution of kingship itself. Norman Hammond, “Preclassic Maya Civilization,” 139, finds evidence of kingship around 400 b.c.:

By the beginning of the Late Preclassic in 400 b.c. we do, however, start to see a totally different society from that envisaged in the village farming model extant a decade and a half ago. In the next six or seven centuries through to the formal beginning of the Classic period, a true civilization emerges.

. . . .Rulers used these mats, and the mat had the equivalent meaning to “throne” in our iconography. Here at this small site we have the icon of royal power displayed; were there already rulers by 400 b.c. who had established both the reality of power and its symbolic expression?

For both Evans and Hammond, the relevant evidence comes from architecture. It is entirely plausible that the forces moving towards kingship preceded the kings who assembled the labor required to document their power in community architecture. The beginning dates are not entirely clear, with the earlier side comfortably supporting Nephi’s kingship.

[14] Charles W. Golden, “The Politics of Warfare in the Usumacinta Basin: La Pasadita and the Realm of Bird Jaguar,” 32, makes a parallel observation: “Though an increasing number of titles apparent in the epigraphic record may reflect an increase in the number of titled personages within Maya polities during the Late Classic, there is no reason to believe that many such individuals were not present in Early Classic society.”

[15] Julia Guernsey, “Rulers, Gods, and Potbellies: A Consideration of Sculptural Forms and Themes from the Preclassic Pacific Coast and Piedmont of Mesoamerica,” 257.

[16] John S. Henderson, The World of the Ancient Maya, 111–14 (intervening photographs).

[17] Ross Hassig, War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica, 56.

[18] Charles W. Golden, “The Politics of Warfare in the Usumacinta Basin: La Pasadita and the Realm of Bird Jaguar,” 45.

Hassig, War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica, 166: “Economics may well be a major motive behind imperial expansion, but it is the military that makes empire possible, just as it underwrites a tribute system within the state. Moreover, the relationship between economics and military expansion is frequently reciprocal, with the potential for adequate gain determining whether or not the expansion is undertaken. But the potential profitability of a trade relationship does not determine whether political expansion will take place; military capacity does.”

[19] James N. Ambrosino, Traci Ardren, and Travis W. Stanton, “The History of Warfare at Yaxuná,” 122–23.

[20] Brant A. Gardner, “The Gadianton Robbers in Mormon’s Theological History: Their Structural Role and Plausible Identification, presentation at the August 2002 FairMormon Conference, http://www.fairmormon.org/perspectives/fair-conferences/2002-fair-conference/2002-the-gadianton-robbers-in-mormons-theological-history-their-structural-role-and-plausible-identification

[21] Hassig, War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica, 57–58.

[22] William L. Fash and Barbara W. Fash, “Teotihuacan and the Maya: A Classic Heritage,” 448.

[23] David Stuart, “‘The Arrival of Strangers’: Teotihuacan and Tollan in Classic Maya History,” 466:

The potential importance of the hieroglyphic texts is clear, but it is surprising how seldom they have been used to clarify the history underlying Teotihuacan-Maya interactions. With the exception of Proskouriakoff, most epigraphic work on central Petén history has assumed a more “internalist” perspective, often ignoring the Teotihuacan issue altogether. I offer a very different perspective in this essay, arguing that hieroglyphic texts at Tikal, Copán, and other Maya sites offer insights into Maya perceptions of a dynamic and often changing relationship with central Mexico. As we shall see, such sources strongly support a more “externalist” view that Teotihuacan played a very direct and even disruptive role in the political history of Maya kingdoms.

[24] Heather McKillop, The Ancient Maya: New Perspectives, 315, pictures Nun Yax Ayin of Tikal in “Teotihuacan style military regalia.” Stuart, “The Arrival of Strangers,” 468–69, discusses figures in Teotihuacan military attire. Fash and Fash, “Teotihuacan and the Maya,” 443–45, discuss burials including Teotihuacan military regalia.

[25] Michael D. Coe, The Maya, 83.