I took my first deep dive into the pool of polygamy research while collecting information about a nineteenth-century Mormon women’s activist, Ruth May Fox. I was working on my master’s thesis and recognized it was essential to tackle this topic to understand the world she lived in. What I found was uncomfortable. I wanted history to be neat-and-tidy, and, instead, history was messy, inconsistent, and troubling. I was raised LDS and lived where there were relatively few Mormons. Once people found out I was Mormon, they would often ask about polygamy. My ingrained response was to quickly emphasize that we no longer practiced it. For me, it was piece of our past to reject, and even feel ashamed or embarrassed about. It was not modern Mormonism, and that was enough for me.

I did not have the inclination to study Church history until it became necessary to do so for my studies, and I was introduced to a rich and incredible world of Mormon womens’ history that I had no idea existed. I have had glimpses of the deep sisterhood they shared, united by faith through persecution; a unity in large part achieved due to their participation in and defense of polygamy. I have since come to view plural marriage as a part of Latter-day Saint history to unapologetically own, and to hold as one of the most valuable testaments of faith in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Four Puzzle Pieces

Theologians and historians have studied the nooks and crannies of Mormon polygamy for over one hundred years, producing unnumbered works addressing aspects of the practice. Writers and readers are motivated to return to the topic again and again, wanting answers to potentially unanswerable questions, like what motivated men and women to enter polygamy? Were their experiences negative or positive? Was it a divinely inspired practice or merely a man-made excuse to fill base human passions? Were women really happy in plural marriage? What percentage of Mormons actually practiced polygamy? And so forth. These questions are complex, and not one answer can satisfy all questions adequately.

Experiences in plural marriage can vary as widely as those in monogamous marriage. It, too, was colored by human strengths and frailties, successes and seeming failures, joy and heartbreak. Creating blanket statements about polygamy cannot apply anymore than saying all monogamous marriages were happy and all plural marriages were sad. Nor can we say that every woman in a monogamous marriage had greater chance for happiness and marital satisfaction than women in polygamous marriages. Nor can we suppose that all women felt more or less loved when sharing a husband vs. being his sole companion. These questions are as individual as there are people.

That being said, there are patterns and similarities researchers can track, and careful evaluations and interpretations can be made. There are strategies, tools, and resources that can help enrich our understanding of polygamy.

I suggest these four puzzle pieces as essential building blocks for creating a more complete picture of plural marriage. There are certainly more puzzle pieces that could be added, but in my mind, the union of these four give a strong foundation to build upon. For one person, a single puzzle piece may be enough to satisfy an inquiring mind. However, a person cannot look at one puzzle piece and think she sees the whole picture. All can benefit from having these pieces put together. These four puzzle pieces have helped me to understand polygamy more fully and to see it more clearly. They are:

- Theology

- Accurate historical sources

- Historical context

- Experiences of those who practiced plural marriage

The first piece is:

THEOLOGY

I will give only a very brief sketch of the theological tenets framing the practice of polygamy. Latter-day Saints believe that God restored the Church of Jesus Christ through the Prophet Joseph Smith. He helped to usher in a restoration of all things, including a restoration of the priesthood, which is the proper authority to act in God’s name on earth.

In biblical times, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, and others practiced plural marriage. By revelation, Joseph Smith believed this was an aspect of the gospel that needed to be restored and practiced once more. Church leaders looked to the scriptures for guidance. The Book of Mormon identifies one reason God would reinstitute polygamy, and that is to increase the number of children born to “raise up seed unto [the Lord].” (Jacob 2:30). In the Bible Abraham was promised by God to have progeny as limitless as the sands of the sea, and it was plurality of wives that made the fulfillment of Abraham’s promise possible.

Many nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints were Millenialists, believing Christ’s Second Coming was eminent, even at their door. They looked to the scriptures and saw that in the Last Days “seven women shall take hold of one man, saying, We will eat our own bread, and wear our own apparel: only let us be called by thy name, to take away our reproach.” (Isaiah 4:1). Some Church members interpreted this to signify that the restoration of plural marriage was required before the Second Coming of the Lord. This is not an official theological interpretation of the scripture, but it was oft-quoted then by defenders of the faith to substantiate the practice, and it influenced men and women to marry polygamously because, in their view, it was the latter days.

During Joseph Smith’s lifetime, polygamy was practiced quietly. It became progressively more open once the Saints arrived in Utah.

Finally, in August 1852, Orson Pratt was instructed to publically announce that plural marriage was a tenet of the Latter-day Saint faith. In that sermon, he said it was “well known . . . to the congregation before me, that the Latter-day Saints have embraced the doctrine of a plurality of wives.”[1] He quickly stressed that plural marriage was, “not a doctrine embraced . . . to gratify the carnal lusts and feelings of man,” but instead allowed righteous men and women the opportunity to have “a numerous and faithful posterity to be raised up and taught in the principles of righteousness and truth.”[2] He cited the blessings of Abraham. By revelation, now was the time to have those blessings restored to members of the Church. He concluded his remarks by glorying in God for the sealing power, for the revealed keys to seal all couples (monogamous and polygamous) for eternity, joining them beyond the grave.[3]

ACCURATE HISTORICAL SOURCES

The second puzzle piece is accurate historical sources. History is only as good as your sources. The best sources are contemporary records, those records kept at the time an event occurred. Preferably, the records were written by someone closely connected to the person or event you are researching. The richest resources are often life writings, which are typically autobiographies and reminiscences, journals and diaries, and letters. Autobiographies and reminiscences are very valuable to draw from, especially if they’re the only record you have, but diaries, journals, and letters have special historical power. They were written in the moment events were occurring. The person you’re researching may be in the midst of decision, transition, or fierce emotion. They do not yet know how things will unfold. They do not yet know the end of the story, whereas the autobiographer does. Letters are fantastic sources because they give you a one-sided conversation, as if you are “talking” with the person. Memories are fresh, the sequence of events is apparent, and emotions are typically present (they may not be in journals), giving you special insight into people and events.

Now comes the tricky part. You may be thinking, “Great! I have a typed copy of my ancestor’s autobiography or journal—I’m set.” Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Your typescript is only as good as the transcriptionist, and sometimes there are drastic differences between the typescript and the original handwritten sources. Drill down to the most original source you can get. Keep in mind that the farther you are removed from the original source, the sketchier details become. For example, a daughter reminiscing about her mother is usually a stronger source than a great-granddaughter recalling the stories her grandmother used to tell about the same ancestor.

Sources are especially important when looking at polygamy. Access to primary, contemporary records is your best bet to answering the juicy questions people often thirst to find out about polygamy, such as “What happened? How did you feel? Why did you do this?” Let me give you an example:

Before I began researching the life of Ruth May Fox (who happens to be my ancestor), I knew she was the first wife in a polygamous marriage. All I knew about her experience was the vague eavesdropping of family tradition and one cryptic paragraph from Ruth’s autobiography. From what I gleaned, Ruth was taken completely by surprise by her husband, Jesse’s, second marriage. Thereafter, he apparently abandoned Ruth to live with his second wife, Rose.

As I began digging through original records, I found both of those suppositions to be completely false. I was able to locate original letters, contemporary city records, newspapers, journals, records from Rose’s family, oral histories, and also attained greater historical context to illuminate what was actually occurring. Through letters written by Jesse and Rose’s own records, I found that Ruth indeed was aware that Jesse was courting a second wife and she accepted their relationship (albeit not with enthusiasm). With these additional sources, I was able to understand the meaning of the cryptic paragraph in Ruth’s autobiography. It also became easily apparent that Jesse and Ruth continued to live together after his marriage to Rose. Points of this story were clarified beyond doubt thanks to primary, contemporary records.

As an aside, lack of primary, contemporary records is probably THE single reason that unpacking Nauvoo polygamy is so difficult. Contemporary sources detailing polygamy during that time are extremely rare because the practice was kept confidential. Most of the sources available are later reminiscences when “the end of the story” was known, and polygamy was well-established in Mormonism. Laura Hales will be speaking about Nauvoo polygamy tomorrow and is an admirable example of one conducting painstaking research to piece together and interpret a complex story with few contemporary sources available.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

So, how do we establish the truth of something historically? We know it is critical to have a basic grounding in theology, find strong contemporary sources, and we also know that the farther sources are removed from the time, typically the weaker and more dubious the stories become.

The third puzzle piece we need is Historical Context. We have to put on a different set of glasses when looking at history. For example, were the men in this picture sinners or saints? It depends who you asked. This is a picture of a group of prisoners in the Utah Penitentiary. They were found guilty of practicing polygamy. If you asked a Mormon, he would say these men were heroes, true Latter-day Saints. Prisoners were often heralded as martyrs for their religion. Upon their return home, some of these men may have had parades held in their honor. On the other hand, if you asked a typical legislator in Washington, D.C. about these men, chances are he believed that these polygamists belonged in prison for a crime against women. Our forbears, whether Mormons or gentile legislators, were balancing a set of needs and navigating social mores different from our own. Viewpoints change over time due to imposed circumstances, cultural exposure, economic prosperity, changing morality, advanced knowledge and technology, and basic generational differences. These filters affect how we in the present view those in the past, and how we tell their stories.

For example, marriage was different in the nineteenth century than it is today. With our twenty-first century glasses on, marriage is based on ideals of romantic love. Marrying without romantic attachment seems sad or unfair—even impossible. But not all saw it that way in the nineteenth century. In most parts of the Western world, women had few legal rights and little economic security without a husband. Having a male protector typically gave women and children a more stable life. Adding another dimension, like religious faith, into the mix, further affected the criteria with which women chose a spouse. That being said, as the nineteenth-century progressed, marrying for love became more customary, but it was not considered a pre-requisite for marriage, as is often the assumption in our worldview.

When reading history, it is fantastically illuminating to understand the prevailing cultural ideals. That fact plays an essential role in how members of the Church defended and justified polygamy.

Plural marriage was officially practiced from the early 1840s until the 1890 Manifesto, a half-century spanning nearly the entire spine of the reign of Britain’s Queen Victoria, a time distinguished as the Victorian era. Along with frilly dresses, fringy home décor, and Charles Dickens, the Victorian era is noted for its emphasis on piety and morality, religious revival, and distinct social spheres for men and women. It is also noted for having a rather dirty underbelly—the industrial revolution, for example, decreased the quality of life for many and there was an explosion of what they called “social evils.”

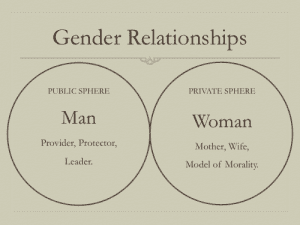

In Victorian gender relationships, men ruled the public sphere where they were employed, politically involved, and held civic and religious leadership positions. They were the providers, protectors, and leaders. The model Victorian woman ruled the domestic sphere of home. She filled her greatest potential in becoming a noble wife and mother, and stood as the moral pillar of society. Woman set the standard for virtue and good works in her community, and was placed on a pedestal of purity, including sexual purity.

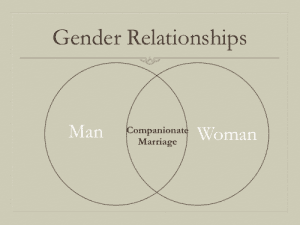

Male and female spheres overlapped through companionate marriage. While there were separate spheres inhabited by model wives and husbands, there was also an ideal husband-wife relationship. Men and women aspired to attain the companionate potential of a loving marriage, believing that the sexes were perfect complements to one another other, and because of this, the perfect companion. In the ideal relationship, a husband and wife took refuge in each another as the others’ closest advisor and confidante. Men were more moral and noble because of women, and women were protected and supported by men.

These Victorian ideals were completely overthrown by the concept of polygamy; it flew in the face of social roles and marriage expectations. The companionate nature of marriage was shattered by the assumption that men’s base desires were motivating them to participate in polygamy, not the desire for the well-being and respectability of his wives.

Social roles for men and women unraveled as well. People heard tales of plural wives left destitute and men neglecting the economic support of their families—the men, therefore, were not filling their social role as providers. The public envisioned polygamist men as despots and dictators over their families—thus not filling their role as protector.

I mentioned earlier that women were held on a pedestal of morality and sexual purity. As such, in the Victorian era there became a cultural fixation on women’s sexual purity. Respectable women were chaste and reserved sexual relations for monogamous matrimony. Any woman who had sexual relations outside of marriage was considered “fallen” and was a disgrace to those associated with her.

Ironically, however, in tandem with this social emphasis on sexual purity, there was an explosion of prostitution, which was considered one of the greatest social evils. Under the prevailing code of womanly respectability and purity, nineteenth-century Mormon women were scorned and accused of being adulterers, prostitutes, and concubines. If the women were thus degraded—women who were supposed to set the standard for virtue in their communities—popular culture deduced that Mormons must certainly be a deplorable, dysfunctional, and immoral group indeed. If women were thus enslaved, there was no hope of the amelioration of the Mormon people.

Polygamist Mormons felt a great dichotomy between how they were perceived by popular culture, and the reality of their situation.

Historian Joan Iverson was keen to observe that Mormons used the same cultural ideals to defend themselves against negative perceptions. They also used the same ideals to measure themselves as men and women. Instead of finding themselves falling short, Mormons found themselves exceeding the ideals of Victorian culture in many ways.

Women defended plural marriage by saying it allowed all women who desired to reach their full potential and become honored wives and mothers. They felt confident in the goodness of their husbands and took their domestic role seriously. They cited the health and well-being of their children as a manifestation of this. Mormons also believed that polygamy eradicated one of the greatest social evils of their time: prostitution. In fact, in Orson Pratt’s speech officially announcing plurality of wives in 1852, he addressed the thorn of adultery in modern Babylon, and believed polygamy prevented prostitution and adultery, thus further separating Zion from the world. Women who would otherwise be prostitutes could become honored wives and mothers with “legitimate” children.

Additionally, Mormon women felt they filled the role as moral pillar of society and set a standard for good works in their communities. Their choices were based on strict religious faith and many of their efforts were consecrated to building the kingdom of God and their communities. Utah women were very proud of the advancements for women in their society. Utah created comparatively liberal laws, in part to allow polygamous households to function adequately. Unlike other parts of the Western world, women could own property, find gainful employment, divorce easily if unions were unhappy, and vote as early as 1870. Women were also not prevented from attending institutions of higher education. These liberal practices would have surprised those convinced of woman’s helpless and hapless condition in Utah.

EXPERIENCES & TESTIMONY

Every woman’s story for entering polygamy is different, but there are strands of similarities that motivated women to participate in the practice. Men also have stories that need to be told, but, for today’s purposes, I will focus on the shared patterns of women’s stories.

Popular explanations for plural marriage today include, “Women married in polygamy because their husbands died while crossing the plains and they had five children to take care of and no spouse.” That was the answer I grew up with. Although that may have been true for some women, in large part women married in polygamy out of deliberate choice, not out of desperation.

I. Religious Conviction: Highest eternal reward

The majority of Mormon women entered polygamy because of religious conviction. They believed in the divine restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ through Joseph Smith, and placed immense faith in the words of the prophets—God’s mouthpieces on earth. Those prophets preached polygamy as a divine principle, and “true Latter-day Saints” accepted it. Many adherents believed that by participating in the sealing ordinance, particularly that of plural marriage, they could elevate their standing before God in the after life. Because of that conviction, Mormon men and women participated in a complex, hotly-debated marriage system in the name of faith.

Under the umbrella of religious conviction, Latter-day Saints practiced plural marriage because they believed it was a commandment of God as revealed through His prophets, they hoped for blessings in the world to come for themselves and their posterity, they wanted to raise a righteous posterity, they were counseled to participate in polygamy by Church leaders, and they were converted to do so be scriptural and prophetic evidence.

Again, in my experience reading the stories of women who practiced polygamy, almost all include some element of testimony affirming that they believed the practice was of God and was a divine principle, even if they eventually discontinued the practice or even left the Church entirely. I selected several stories to illustrate women entering polygamy primarily because of their conviction that plural marriage was a commandment of God, but could have chosen many more.

Sarah Barnes Layton (1826-1899) converted to the gospel as a young woman and was baptized in England in 1842. When the opportunity came for Sarah to marry a polygamist, she reflected,

I realized I had covenanted to serve the Lord [at baptism], and I could not deny that one of His orders [was] for us to obey if we would secure the highest degree of glory. . . . The struggle to decide whether or not to enter that order of marriage caused me to lose many a night’s sleep, and caused me to utter many a ferve[n]t prayer to the Lord that He would guide me. . . .

I had believed the principle to be true for a long time, and had heard one of the apostles of this dispensation declare that the Lord had given revelation telling the people that they were to enter into that principle if they would have the highest degree of glory. I had covenanted to serve the Lord; I had obeyed the first principles of the Gospel, and in that I was told that I must not stand still but must go on. . . .

I told my Heavenly Father that if He would give me strength I would obey this principle and would do the best I could trying to live up to it.

Sarah chose to become a plural wife in 1852. In her old age wrote in her autobiography, “I believed that I did right then, and I think so till this day, for the principle is true, but there are many hills to climb along that road, and I have climbed a few, but am satisfied.”[4]

Twenty years after Sarah Barnes married for the sake of religious faith, a Presbyterian named Elizabeth Kane spent several months in Utah with her husband Colonel Thomas L. Kane. Although not LDS, Colonel Kane was beloved by Utahns for his fair representation of Mormons in the national legislature. He and Elizabeth were warmly welcomed into Mormon society. As Elizabeth traveled through Utah, she was let into the hearts and homes of polygamous women, and made a careful record of her experiences. In their discussions about polygamy, Elizabeth noted the same phenomenon: many plural wives dutifully chose marriage partners in anticipation of future eternal blessings. For example, Elizabeth visited an anonymous “lovely-looking woman” who said, laughingly, “Oh Mrs. K. don’t you ever consent to give your husband another wife! It’s a perfect pleasure to see one woman as happy as you are.” Upon Elizabeth’s second visit, the lovely plural wife wished to explain her previous remark. She said “she had not been envious: . . . she was perfectly satisfied with her condition as a plural wife, and thought her husband the best man on the whole earth. She admitted that if she had married the young man whom she had once loved in the ‘States’ and she had been henceforward his one darling wife that her earthly felicity might have been greater. But he was poor, they were very young, and when she joined the Saints he parted from her. And he turned out badly; so that she might have been very wretched.” Instead, she had married polygamously to “receive the highest elevation in the next world.” Elizabeth replied, “if I could obtain the very lowest place in Heaven; could gain admission there at all in fact; I would be more than content, and would not wish to gain a higher place by losing my undivided ownership of a husband here.” The lovely-looking woman, content with her lot, merely “laughed merrily.” [5] Her choice to marry in polygamy was deliberate; it gave her the freedom and satisfaction to achieve her ultimate aim: that of the eternal reward through the sealing ordinance.

As a bookend to the religious conviction motivating women to enter polygamy, it was equally jarring when the 1890 Manifesto announced the discontinuation of the practice.

Lorena Washburn Larsen (1860-1945) married Bent Rolfsen Larsen in 1880 and lived with his first wife for the first seven years of their marriage. “In all that time,” wrote Lorena, “we never quarreled—not once, but I cannot say that we didn’t sometimes feel like it; but we had gone into that order of marriage because we fully believed God had commanded it, and while we had human nature to contend with, we worked and prayed for strength to overcome selfishness and greed and live on a higher plain, learn to love each other, or there would never be happiness in that order of marriage our hearts and homes.”[6] In 1887, the legal noose tightened around polygamists, and Lorena moved from home to home with her children to help protect her husband from legal prosecution and imprisonment.

And then the 1890 Manifesto was announced. At the time, Lorena was traveling with her husband to yet another home for their family. When she heard the news, she recalled,

My husband came to our tent and told me about it, and my feelings were past description. I had gone into that order of marriage solely . . . because I believed God had commanded his people to do so, and it had been such a sacrifice to enter it, and live it as I thought God wanted me to. And as I thought about it, it seemed impossible that the Lord would go back on a principal which had caused so much sacrifice, heartache, and trial before one could conquer one’s carnal self, and live on that higher plane, and love one’s neighbor as one’s self. My husband walked out without saying a word, and as he walked away I thought, Oh yes, it is easy for you, you can go home to your other family and be happy with her, while I must be like Hagar, sent away.

My anguish was inexpressible, and a dense darkness took hold of my mind. I thot that if the Lord and the church athorities had gone back on that principle, there was nothing to any part of the gospel. I fancied I could see my self and my children, and many other splendid women and their families turned adrift, and our only purpose in entering it, had been to more fully serve the Lord. I sank down on our bedding and wished in my anguish that the earth would open and take me and my children in. The darkness seemed impenetrable.

All at once I heard a voice and felt a most powerful presence. The voice said, “Why this is no more unreasonable than the requirement the Lord made of Abraham when he commanded him to offer up his son Isaac, and when the Lord sees that you are willing to obey in all things the trial shall be removed.”

There was a light whose brightness cannot be described which filled my soul, and I was so filled with joy, peace, and happiness that I felt that no matter whatever should come to me in all my future life, I could never feel sad again. If the people of the whole world had been gathered together trying with all their power to comfort me, they could not compare with the powerful unseen Presence which came to me on that occasion.

And as soon as my husband came back I told him what a glorious presence had been there, and what I had heard. He said, “I knew that I could not say a word to comfort you, so I went to a patch of willows, and asked the Lord to send a comforter.[”][7]

Before the cessation of plural marriage in 1890, members of the Church were sometimes pricked by their own spiritual guidance to practice polygamy. When done in proper order, permission was obtained from the first wife and then men approached Church leaders for permission to take another wife. In some cases, however, people were approached by Church leaders and asked to participate in the practice.

If you went back in time and visited wealthy LDS men, General Authorities, and nineteenth-century leaders of wards and stakes, you would find that many had something in common: they were polygamists. Men who were financially stable and held responsible Church leadership positions, such as those in bishoprics or stake presidencies, were often counseled to take a plural wife to set an example for those in their congregations. Margaret McNeil Ballard wrote,

My husband, being a Bishop, had been counseled by the authorities to set the example of obedience by entering into this law [of polygamy]. The compliance of this was a greater trial to my husband than it was to me. He would say, ‘Margaret, you are the only woman in the world I ever want’ . . . While this was a trial for both of us we knew that the Lord expected us to be obedient in this law, as in all laws, as revealed in these the latter days. After many weeks of pondering and praying for guidance, I persuaded my husband to enter into this law and suggested to him my sister, Emily, three years younger than myself, as his second wife. . . .

They decided to be married . . . in the Endowment House. Henry asked me to go with them on this trip. I made a protest as I was in a delicate condition [pregnant]. Henry was grieved and said to me, ‘Margaret, unless you go with me and give your consent to this marriage and stand as a witness, I will not go.’ I went . . . and gave my consent and blessing to the union. . . . Although I loved my sister dearly, and we knew it was a commandment of God that we should live in celestial marriage, it was a great trial and sacrifice to me. But the Lord blessed and comforted me and we lived happily in this principle of the Gospel.[8]

II. Religious Conviction: Raise up Righteous Seed

Another motivation spurring plural marriage was the opportunity to raise a numerous righteous posterity. Women who otherwise would not have had opportunity to marry a devoted Latter-day Saint man, and likewise childless husbands, would have the opportunity to raise children unto the Lord. Elizabeth Graham Macdonald felt passionately about this concept, saying, a “reason why a plurality of wives is given to worthy men . . . [is] to multiply and replenish the earth. . . . and for the exaltation of all who enter into this holy order; that they may bear the souls of men. . . . Then why should I or any other woman in the Church with-hold this privilege from another because of the feelings of our weak nature.”

She observed that, “A great deal of good can be done in a family of many wives when the man takes a wise course.” She continued, “I bear testimony that the revelation on Celestial Marriage given through the Prophet Joseph, is from God. In my experience I do know that the blessings and promises contained in that revelation are realized when lived for.”[9]

III: Decision to practice plural marriage

The decision to marry polygamously often occurred after having been in a monogamous marriage for some time. For many, especially adult converts, polygyny was not part of their original domestic plan.

Others, however, took a proactive approach. From as early as the 1840s, youth deliberately chose, even before marriage, that they wanted plural families. For example, in the 1840s, Sarah Ballard (who I mentioned earlier) and her friend Sarah Martin promised one another that they would marry the same man, and they did. In the 1850s, sisters Sarah Maria and Amanda Mousley agreed “to share with each other, their lot in marriage” and were married to Angus Cannon on the same day.[10]

Two generations later in the 1880s, young people were still making deliberate plans for plural marriage.

Ellen Larson and Silas Smith began courting one another in Snowflake, Arizona. As their courtship developed, Silas wrote that they often “knelt in prayer asking our Heavenly Father to protect and guide us. We talked of the future and exchanged ideas; we both agreed that some day we would live the principle of polygamy.”[11] Ellen’s family moved to Pima, Arizona, not long after she and Silas vowed to marry. They corresponded with one another, and one day Silas wrote to Ellen of his admiration for a “splendid young lady, Maria Elizabeth Bushman, from St. Joseph, Arizona.” Ellen responded tersely, “I have been thinking seriously about this matter of you taking a second wife and if you are determined to do so, I must ask you to excuse and relieve me now from going any further.” Silas recorded:

Well, I was sick and heart-broken. . . . Alone I pondered and visiting the little cedar trees, I poured out my soul in prayer. I really felt like saying, “Ellen, I will do anything or go anywhere for you.” But my letter read thus, “Ellen, your letter breaks my heart. We have well understood this matter and have been in agreement in contemplating and planning a plural family; it is my purpose to continue in that determination come what will . . .” Sooner than I anticipated an answer came, a short note with this message, “Oh Silas, I love you, forgive me, I wanted to try you to see if you would give up a principle for a poor simple girl like me. I would not have wanted you had you not have proved to me that you are a man. The man I want my husband to be. I love you more than ever, Your Ellen.[”]

The load was lifted; at the little tree I expressed my thankfulness. Although Satan attempted to create anger for being played with, I finally wrote to her saying, “All is well, may God grant us courage to proceed.”[12]

MARRIAGE FOR LOVE

In addition to marrying out of a sense of religious duty or in hopes of elevated celestial glory, many polygamous couples also married for love. As we discussed earlier, the ideal Victorian marriage was companionate; one of mutual love and attraction. And polygamous couples, particularly polygamous wives, yearned for emotional and romantic intimacy with their husbands. Even our lovely-looking woman, interviewed by Elizabeth Kane, owned that her “earthly felicity [if not heavenly] might have been greater” if she had married for love. Some couples were able to achieve an emotional intimacy, others who married for love did not receive the exclusivity they hoped.

Ida Hunt was one such woman. She was in love with her prospective husband, David Udall, and his first wife gave a reluctant blessing for them marry. On May 25, 1882, Ida gushed in her journal, “I was sealed for Time and all Eternity to David King Udall, the only man on Earth to whose care I could freely and gladly entrust my future; for better, for worse. . . . May Heaven help me to keep the vows I have made sacred and pure and may the deep unchangeable love which I feel for my husband today increase with every coming year helping me to prove worthy of the love and confidence which he imposes in me.”[13] Tension with David’s first wife and Ida’s need to go into hiding put strain on her marriage with David. She continued to find joy in her family, but circumstances necessitated that she build much of her life apart from her husband.

Ambitious Martha Hughes married Angus Cannon as his fourth wife. She, too, needed to hide on the underground, and sought refuge in England. She left behind letters to a friend in which she expressed, “I have linked my fate with one that I love. One who seems all but perfection in my eyes.” [14] After her return from England, she became disillusioned over time, as she was unable to have the focused affection from her husband that she craved. He had married two additional wives after Martha, so a total of six demanded his attention. She wrote to her friend, “My anticipations of happy associations with loved ones after my long exile were altogether overdrawn. . . . Look long and wisely before you chose a life companion, for tis deathly martyrdom to be linked to one who understands you not, and appreciates you less.” [15]

Julina Lambson Smith, the second wife of President Joseph F. Smith, took joy in the companionship she felt with her husband, sister-wives, and their mutual children. She described her family as a “triangle of happiness” with her husband acting as “the center controlling bond of love.”[16] Joseph wrote to his wives that, “My family, my beloved companions and our little ones, one and all, form the center of attractions for me on this earth.”[17] Ann Agatha Walker Pratt described her husband, Parley P. Pratt, as “a very fine man, a true and loving husband always.”[18] Passionate love letters remain between Parley and Agatha, which are…passionate…and I will leave the contents to your imagination. He had the singular ability to make each of his wives feel “beloved of his bosom.” [19]

In short, was it possible for a husband to have several wives and love each one? Elizabeth Kane, our observant gentile, was surprised to find that indeed she observed romantic love in the homes she visited. Many times she came across a particularly loving husband and Kane would exult, “Here, at last, is one man, high in Mormon esteem, yet a monogamist.” Then she would be dumbfounded to find that there were yet other wives, to whom he showed equal affection. After observing that question historian Claudia Bushman concluded, “If a parent might love several children individually with a great love, perhaps a husband might also love and value several wives as individuals.”[20]

To sum up, looking at theology, sources, context, and experiences has led me to conclude that some plural marriages were better than others. Polygamy often produced unique challenges and brought personal pain. People had various coping mechanisms for meeting those challenges and that pain—some good, some not so good. Some did not adjust well and lived in discord, or eventually sought divorce. Many women did adjusted and found happiness in the order. It is quite incredible to me that, despite its personal challenges, many women lived faithfully in the practice and allowed it to “burn out their jealousies” finding heavenly and earthly satisfaction in the principle, as well as love and companionship.

My understanding and reconciliation with polygamy transformed not as I learned about it in academic books or articles—although that is extremely important for a well-rounded grasp—but when I began studying the experiences of the women who actually lived in polygamy, who chose it as a lifestyle. Day-to-day lived polygamy. What united them all, however, both negative and positive, was their testimony of the truthfulness of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The history of polygamy in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-days Saints is not something to dismiss or quickly define only by its disconnect to the present (that it’s something we no longer practice). Instead, it a legacy of faith to honor and acknowledge, a history to gain great strength from, a foundation of sacrifice to celebrate, and a bright testimony borne in the lives of those who practiced plural marriage in the name of religious conviction.

For me, I no longer feel the slightest iota to downplay the history of plural marriage in the Latter-day Saint faith. On the contrary, I believe it is an incredible legacy of faith given to us by those who sacrificed deeply for what they believed to be a commandment of God. For me, learning about the personal experiences of women who actually practiced plural marriage has changed everything. Reading their testimonies, reading their determination to for the principle in the name of faith, and then to also abandon the principle in later years took an incredible amount of devotion. This was not just a one-time event, this was a day-to-day lived polygamy experience.

Q&A

Question 1: How did the Edmunds-Tucker Law change LDS policy concerning polygamist marriage?

Answer 1: That was one of the laws that tightened the noose around polygamists. Basically it just caused people to go underground more, to hide more. It was more difficult to perform plural marriages during that time, so that’s when you get stories of people going in the night to the Endowment House and being sealed. So LDS policy at that time–it probably affected more LDS practice than LDS policy.

Question 2: Are you in favor of polygamy?

Answer 2: That’s a difficult question to answer. I believe that it accomplished a lot of good things. Just out of curiosity, if you are a descendent of a polygamous family, would you mind standing up? [Many in the audience stand up.]

Thank you. That was very impressive. I think we can all see the fruits of polygamy. So, in that way, in expanding the kingdom, I think it was an important and good thing for the time.

Question 3: Was monogamous marriage looked down upon in the LDS community during the practice of polygamy?

Answer 3: That’s a great question, and one that I have been curious about. We hear a lot about polygamous wives. What about the monogamous wives? We know from different studies that have been done that the majority of people were not polygamous. The most recent figures are that no more than 25 or 26 percent of people practiced. At the highest point of polygamy during the 1850s it could have been as much as 50 percent, but it decreased after that. I don’t know and I hope someone finds out and writes a really good article about it.

Question 4: To what extent was the selection of another wife guided or selected by the first or earlier wives?

Answer 4: You have heard of couples today that there was guidance by the first wives at times. They would suggest a sister of some lady older than them that wasn’t attractive. They did have input, but there were also times like in my ancestors’ case where Jesse did not consult with her about who he wanted as a second wife. He chose someone who happened to be younger than her and very beautiful. This person also says, “There is a very special sisterhood, ” and I believe that there is between the polygamous wives. There have been accounts where the polygamous wives talked about the special unity that they shared. More than sisters, because they were united in purpose in what they believed was a great cause of helping to raise each other’s families.

[Indicating the stack of question cards remaining] Polygamy is a great topic for discussion!

Question 5: Did some divorced plural wives remarry?

Answer 5: Yes. It was comparatively easy to obtain a divorce in Utah, unlike countries like England, where it was expensive and almost impossible. Some people joked about how easy it was to also find another husband. There was flexibility in marrying, so divorced wives did remarry if they wanted to.

Question 6: Was the commandment for the practice of polygamy given to the Church as a whole, or directed toward specific members?

Answer 6: That’s a good and probably complicated question. We know from the way it was practiced that there was some structure to it. Men were discouraged from taking plural wives if they could not support them well, and the General Authorities were encouraged to practice polygamy. The sense that I have gotten is that it was given as a whole as a principle, but a mandate whether or not to practice it did not exist.

Question 7: There are quite a few questions about the FLDS church.

Answer 7: I don’t know that much about the FLDS and how it compares to 19th century polygamy. Someone said something interesting that may be worth contemplating. They observed that perhaps the way we look upon FLDS people is the way that other people looked at us Mormons in the 19th century. For me that has been an interesting thing to think about. I don’t know how the FLDS practice is of plural marriage.

Question 8: Is there any reason to believe that children of polygamous marriages were more faithful than other children?

Answer 8: I don’t think so. I think that just like families now there are all sorts of different elements that influence how a child grows. There may have been a different context and faithful environment, but again, a lot has to do with personal decision.

Notes

[1] Orson Pratt, “Celestial Marriage,” Journal of Discourses , 1:54.

[2] Pratt, “Celestial Marriage,” 1:62.

[3] Pratt, “Celestial Marriage,” 1:66.

[4] Sarah Barnes Layton, Autobiography, typescript, personal possession, n.p.

[5] Elizabeth Kane, A Gentile Account of Life in Utah’s Dixie, 1872-1873 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Library, 1995), 21-22.

[6] Larsen, “Life Sketch,” 144, 145-1.

[7] Larsen, “Life Sketch,” 239-41.

[8] “Margaret McNeil Ballard,” Happenings in the Valley, Our Pioneer Heritage (SLC: DUP, 1960), 3:203.

[9] MacDonald, Autobiography, 38-44.

[10] Warner, “In Search of the Mousley Heritage,” 29.

[11] Smith, “Life Story,” in Silas Derryfield Smith, 34.

[12] Smith, “Life Story,” in Silas Derryfield Smith, 34-35.

[13] Udall, Journal, 27-28.

[14] Hughes Cannon to Replogle, August 6, 1887.

[15] Hughes Cannon to Replogle, August 10, 1888.

[16] Julina Smith, “A Loving Tribute to Sarah Ellen Richards Smith,” Relief Society Magazine 2 (May 1915): 215.

[17] Joseph F. Smith to Sarah E. Richards Smith, October 22, 1884.

[18] Hatch, “Ann Agatha Walker Pratt,” 13.

[19] “Reminiscences of Mrs. A. Agatha Pratt,” 1907, Typescript, pp. 1-2, Church History Library.

[20] Claudia Bushman, “Mormon Domestic Life in the 1870s: Pandemonium or Arcadia?” Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lecture Series, 7 Oct 1999, 22.