This is a brief survey of the use of aversion therapy to “treat” homosexual behavior. It focuses particularly upon the period 1970–1980. The paper is available for download here.

“Some present-day activists want to make McBride’s work into the irrational work of a religiously fanatical and homophobic Church. It was not. It was mainstream, peer-reviewed science.”

Introduction to Aversion Therapy

What is “aversion therapy”?

Aversion therapy is a group of techniques intended to help control unwanted behavior, a type of “behavioral therapy”. The basic idea is that an undesired behavior is paired with something unpleasant. Due to conditioning, the animal or person receiving the therapy comes to associate the unwanted behavior with the unpleasant experience, and thereafter avoids the unwanted behavior.

A simple example would be of a cat that jumps onto a kitchen counter. Many pet owners will spray the cat in the face with a squirt bottle. The cat is not harmed by the water, but does not like it—and so eventually learns not to jump on the counter. (Many pet owners can report that the cat soon avoids the counter—at least when its owner is around to apply the squirt bottle!)

What were the origins of aversion therapy?

One recent history says:

Aversion therapy was a post-war subdivision within a set of psychological and psychiatric treatment methods grouped under the term ‘behaviour therapy’. Behaviour therapy was an elaboration of classical reflex conditioning developed by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the early decades of the 20th century and further investigated by his American contemporary, John B. Watson.[1]

[1] Kate Davison, “Cold War Pavlov: Homosexual aversion therapy in the 1960s,” History of the Human Sciences 34/1 (2021): 92.

Why did behavior therapy and aversion therapy arise?

Psychiatric practice drew heavily on Freudian theory prior to World War II. Freud saw mental illness and some other behavioral difficulties as evidence of delayed psychosexual development.

Freudian psychoanalysis and other “psychodynamic” talking cures were lengthy, expensive, labor-intensive, and not terribly helpful for many issues. There was also a growing recognition that Freud’s claims were unscientific, or difficult to assess with scientific tools.

Researchers were seeking better methods to help patients that would be quicker, more effective, and more easily studied scientifically.

Behaviorism was appealing because, unlike Freudian theory, one did not need theories about what went on “inside the mind.”[2] (One early theorist, John B. Watson, “denied completely the existence of the mind or consciousness”![3])

Even for those who did not go so far, there was little worry about the subconscious, or the Oedipus complex, and so on.[4] One could simply study a stimulus (the aversion) and the resulting behavior. Both of these were external, and thus open to scientific observation.

[2] For a summary of the Freudian position, see Charles W. Socarides, “Sexual Politics and Scientific Logic: The Issue of Homosexuality,” Journal of Psychiatry 19/3 (Winter 1992): 318–320.

[3] Matt Jarvis, Theoretical Approaches in Psychology (Routledge: London and Philadelphia, 2000), 14. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Watson eventually left research and went into advertising.

[4] Joel Fischer and Harvey L. Gochros, Handbook of Behavior Therapy with Sexual Problems, 2 volumes (Pergamon Press, 1977), 1:xliv.” [B.F.] Skinner believed that we do have such a thing as a mind, but that it is simply more productive to study observable behaviour rather than internal mental events” (Jarvis, 17).

Sexual orientation: changing vocabulary and concepts

How did Freudian theory impact behavioral therapies?

Many psychoanalysts believed

that sexual habits, orientation, and psychosexual structure were not rigid. They believed that ‘a variety of methods could allow some patients to have heterosexual desire … or significantly reduce or practically eliminate the appeal of the same sex for at least some time’.[5]

As the previous citation demonstrates, our ideas and even vocabulary about sexual orientation has changed considerably since World War II. It is important to understand how words were used at the time they were used, so we do not misunderstand what scientists were saying.

In 2022, most people believe that each individual has a “sexual orientation”—a fixed, life-long pattern of sexual attraction that is largely resistant to change.

We lose sight of how recent an idea and terminology this is.

[5] Davison, “Cold War Pavlov,” 96, italics in original.

What did “sexual orientation” mean during the 1970s?

There was considerable flux in terms at this period. As late as 1984, researchers complained that different scientists used the terms “homosexual” and “sexual orientation” in different ways.[6] Some used it to refer only to behavior. Other used it to refer to inner desires. Others used it to describe the origin of feelings and desires, and so on.

In the mid-1970s, one gay rights group preferred that people refer to “sexual orientation,” because they said it reflected what people did, not simply what their desires were:

1.The term “affectional or sexual preference” is defined…as “having or manifesting an emotional or physical attachment to another consenting person or persons of either gender, or having a preference for such attachment.” This is vague and appears incomprehensible. …”Sexual orientation” defined in some existing legislation as “choice of sexual partner according to gender”) is at least quickly comprehensible, and more clearly encompasses homosexual behavior.

2. It diverts attention from the real source of homosexual oppression—the fact that we engage in sexual acts that are forbidden and criminal in our society. Neither homosexuality per se nor homosexual lifestyles are illegal in any state in the United States; it is certain kinds of acts that are illegal. …

4. It tends to obscure the reality…that human sexual behavior falls on a continuum between those who are exclusively heterosexual and those who are exclusively homosexual. …

This language both trivializes and obscures the struggle that gay liberationists are involved in: to argue and insure [sic] that sexual acts committed between consenting partners should not be punished.

6. It represents a concession to the prevailing heterosexual view that sex is good and justifiable only when it is complemented by “love.” Equal rights must be extended to homosexuals regardless of whether or not they are emotionally or physically attached to another person.[7]

As one author noted:

For this advocacy group, “homosexual orientation” “more clearly encompasses homosexual behavior.” Using their preferred term focuses on “sexual acts that are forbidden,” rather than focusing on “homosexuality per se” “nor [even] homosexual lifestyles.” Instead, it highlights that “certain kinds of acts are forbidden,” and since “human sexual behavior falls on a continuum,” they wish “that sexual acts … not be punished.” The term further avoids “a concession … to the view that [the] sex [act] is good … only when … complimented by ‘love’.”

[Thus] in 1975–1977 … a pro-gay group saw “homosexual orientation” and “sexual preference” as quite different things. The former was primarily concerned with behavior, not desire.[8]

The “Kinsey scale” had been published in 1948, and did not see “sexual orientation” in the same sense that we use the term today.[9]

In 1980 [one] author argued that Kinsey’s work demonstrated that “sexual orientation fluctuates, surely over a lifetime and, for some people, as often as the weather.” As evidence, he cited Kinsey’s claim that “Some males may be involved in both heterosexual and homosexual activities within the same period of time. … even in the same day. … Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual.”[10]

This author went on to argue that “homosexual orientation” is actually a cluster of traits including “physical sexual activity,” “interpersonal affection,” and target of “erotic fantasy.” Choice of label was more frequently based upon “physical sexual activity, either as behavior or desire.”[11] Significantly, he concluded, “Sexual orientation is one of the few areas of human behavior in which biology is not destiny.” This is the furthest thing from today’s “sexual orientation,” which most see as innate and unchanging, and unrelated to acts.

It is thus not surprising to see early behaviorists remark that “The Kinsey rating has the merit that it conceives of homosexuality as a graded form of behaviour and not as something which is present in an all or none manner.”

[6] Michael G. Shivley, Christopher Jones, John P. De Cecco, “Research on Sexual Orientation: Definitions and Methods,” Journal of Homosexuality 9/2–3 (1984): 132–134.

[7] David Thorstad (editor), “Sexual Preference vs. Sexual Orientation,” Gay Activist 6/1 (New York, NY; March 1977): 3, italics added, underlining in the original. Though published in 1977, the official statement was “adopted … in early 1975” (3); cited and footnote reproduced with permission from Gregory L. Smith, “Feet of Clay—Queer Theory and the Church of Jesus Christ,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 43 (2021): 204, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/feet-of-clay-queer-theory-and-the-church-of-jesus-christ/.

[8] Smith, “Feet of Clay,” 204.

[9] Kinsey, WB Pomeroy, CE Martin, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (Saunders: Philadelphia, 1948).

[10] Smith, “Feet of Clay,” 205, citing John P. De Cecco, “Definition and Meaning of Sexual Orientation,” Journal of Homosexuality 6/4 (Summer 1981): 57 who in turn is citing Kinsey (1948), 29, 61, 63–64, italics in original, underlining added.

Was aversion therapy intended to “change sexual orientation”?

Because of the varied vocabulary and meanings given to it, this is not as easy a question to answer as we might think. If researchers were not working with the idea that a fixed, life-long orientation existed—and many were not—then they can hardly have been trying to change it, even if that is what the long-term success of their experiments would have amounted to. As one historian of the period said, with the behaviorists

a further innovation was to separate orientation from behaviour, suggesting it might be possible to condition patients’ sexual behaviour in a heterosexual direction irrespective of whether their inner emotional and erotic orientation changed.[12]

Aversion therapy, then, was often not ultimately concerned about whether homosexuals had a fixed “orientation” toward their own sex or not. It was intended to help the patient control unwanted behaviors.

Behaviorism didn’t care so much about what was “inside” a patient—its practitioners were focused on outward acts.

An early example discusses how behavior was “reinforced by [the patient’s] first homosexual experiences, a learned pattern thus being established.”[13] Another early behaviorist approach saw “homosexuality as a learned behaviour pattern and not as a disease.”[14] One early researcher emphasized in a lecture that with aversion therapy “sexual orientation is not changed, but increased awareness of feelings is developed, giving the client greater choice in the expression of these feelings.”[15]

A later example from 1974 tells how researchers rejected the idea that homosexuality was a disease, but likewise argued that it was not something “constitutional,” or innate: “Conceptions of homosexuality as a sickness or as a constitutional personality type were discounted.” Instead, “the therapist gave the client an account of homosexuality as a learned pattern of behavior.”[16]

[12] Davison, “Cold War Pavlov,” 96.

[13] Basil James, “Case of Homosexuality Treated by Aversion Therapy,” British Medical Journal (17 March 1962): 769.

[14] JG Thorpe, E Schmidt, and D Castell, “A Comparison of Positive and Negative (Aversive) Conditioning in the Treatment of Homosexuality,” Behavior Research and Therapy 1/2–4 (1963): 361.

[15] Ronald W. Field, “Book Reviews: A Neo-Pavlovian View of Behaviour Therapy: Tape 2-Aversion Therapy of Homosexuality,” in Medical Journal of Australia (20 September 1975): 489.

[16] Lynn P. Rhem and Ronald H. Rozensky, “Multiple behavior therapy techniques with a homosexual client: a case study,” Journal of Behavioral, Therapeutic, & Experimental Psychiatry 5 (1974): 54, emphasis added.

Is aversion therapy the same thing as “conversion therapy” for homosexuality?

Not exactly. At most, aversion therapy is seen as an early type of conversion therapy. Conversion therapy “is an umbrella term” for a “poorly defined” set of approaches (some secular, some religious) that aim “to suppress same-sex attraction.”[17] Other authors include aversion therapy under a broader rubric of “sexual orientation and gender identity and expression change efforts (SOGIECE),” which “aim to deny or suppress feelings and desires related to non-heterosexual identities.”[18]

Conversion therapy used or uses a wide variety of approaches, including aversion, psychodynamic approaches, hormonal treatment, and religious/spiritual practices such as prayer, exorcism, or scripture study.[19] It occurs in both professional and non-professional forums, “in a remarkably wide range of settings: churches, camps, conferences, online chats, prayer groups, regulated and unregulated counsellors’ offices, and medical offices.”[20]

As the name implies, being a “behavioral” therapy, aversion was focused on behavior, not identity. As we will see, most aversion therapy efforts targeted behavior. Many of the researchers did not believe in a “homosexual orientation” in the modern sense, and so were not focused on changing that.

[17] Travis Salway and Florence Ashley, “Ridding Canadian medicine of conversion therapy,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 194/1 (10 January 2022): E17–E18, https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.211709. For the Church’s current position opposing conversion therapy, see: “Official Statement: Church Continues to Oppose Conversion Therapy,” newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org (25 October 2019), https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/statement-proposed-rule-sexual-orientation-gender-identitychange.

[18] Trevor Goodyear et al., “’They Want You to Kill Your Inner Queer but Somehow Leave the Human Alive’: Delineating the Impacts of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression Change Efforts,” The Journal of Sex Research (19 April 2021): 1.

[20] Salway and Ashley, “Ridding Canadian medicine,” E17–E18.

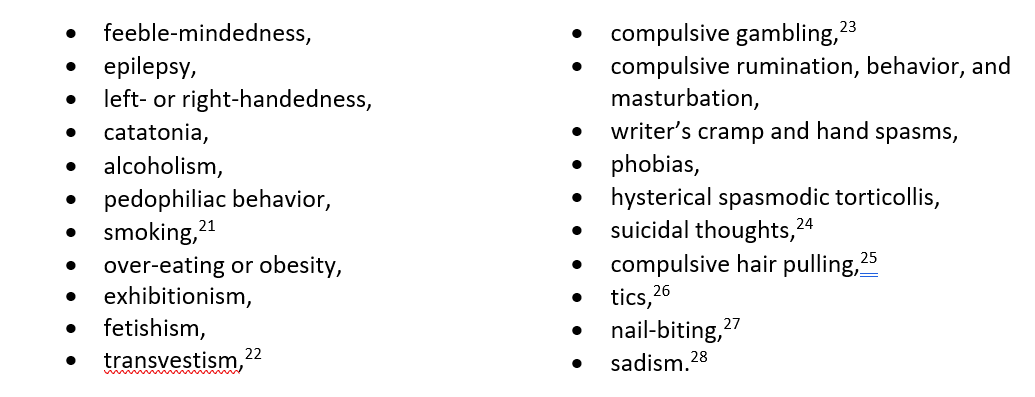

Besides homosexual behavior, what else was treated with aversion therapy?

Aversion therapy is only one type of behavioral therapy. Other behavioral therapies were widely used, though we will not discuss them here. Aversion therapy specifically was used in the treatment of many behaviors, including:

We can see that unlike conversion therapy, aversion therapy was used for far more than homosexual behavior. Psychologists and physicians encountered patients with a wide variety of problems and unwanted behaviors. “Psychodynamic” approaches—the intensive one-on-one talk therapy first used by Freud—were not terribly successful for many problems. They also required hundreds of hours of highly trained professionals’ time, and were thus expensive. Researchers were keen to find something that would be more effective and work more quickly. Aversion therapy was appealing because someone with relatively little training could perform the treatment by adhering to a script. This would magnify the number of patients that could be helped.

We can see that unlike conversion therapy, aversion therapy was used for far more than homosexual behavior. Psychologists and physicians encountered patients with a wide variety of problems and unwanted behaviors. “Psychodynamic” approaches—the intensive one-on-one talk therapy first used by Freud—were not terribly successful for many problems. They also required hundreds of hours of highly trained professionals’ time, and were thus expensive. Researchers were keen to find something that would be more effective and work more quickly. Aversion therapy was appealing because someone with relatively little training could perform the treatment by adhering to a script. This would magnify the number of patients that could be helped.

In the 1970s, aversion therapy was the cutting-edge scientific therapy. We can sense the excitement and optimism even in the dry language of scientific reports.

[21] Mary Eisele Beavers, “Smoking Control: A Comparison of Three Aversive Conditioning Treatments,” Ph D. dissertation, University of Arizona, 1973.

[22] MP Feldman, MJ MacCulloch, Mary L. MacCulloch, “The Aversion Therapy Treatment of a Heterogeneous Group of Five Cases of Sexual Deviation,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 44 (1968): 113–124

[23] N[athaniel] McConaghy, MS Armstrong, and A. Blaszczynski, “Expectancy, covert sensitization and imaginal desensitization in compulsive sexuality,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 72 (1985): 176–187.

[24] John Paul, Foreyt “Control of Overeating by Aversion Therapy,” Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, 1969, 78–114.

[25] C.A. Bayer, “Self-monitoring and mild aversion treatment of trichotillomania,” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 3 (1972): 139–141; Patricia P. Miller, “Trichotillomania: Is Exposure and Response Prevention an Effective Treatment?” Ph D. dissertation, University of Albany, State University of New York, 1998, 7.

[26] Ellen L. Sharenow, “A Comparison of Similar Versus Dissimilar Competing Response Practice in the Treatment of Muscle Tics,” master’s thesis, Western Michigan University, 1985, 1.

[27] J. Vargas and V. Adesso “A comparison of aversion therapies for nail-biting behavior,” Behavioral Therapy 7 (1976): 322–329.

[28] Feldman, MacCulloch, and MacCulloch, “Aversion Therapy Treatment of a Heterogeneous Group,” 113–124.

Motives

Were most of these researchers “homophobic”?

If by “homophobic” we mean “motivated by distaste or hatred toward homosexuals,” then in the main, no. Psychologists and psychiatrists tended to be more liberal in their views about homosexual behavior than society at large.

Many behaviorists were in favor of legal protection for gay citizens, and decriminalization of same-sex acts. Even those psychoanalysts who regarded homosexual behavior as unhealthy generally did not see it as a moral failing, or worthy of criminal penalties or social persecution.[29]

Over time, there was also a growing recognition that persecution and societal factors played a large role in homosexuals’ psychological difficulties.[30]

[29] Charles Socarides, a psychoanalyst who regarded homosexuality as pathological, nevertheless strongly agreed with a report’s call “for society’s toleration and understanding of the homosexual condition and the gradual removal of persecutory laws against such activities between consulting adults. These positions were good and well taken.” [Charles W. Socarides, “Scientific Politics and Scientific Logic: The Issue of Homosexuality,” Journal of Psychiatry 19/3 (Winter 1992): 310.] He also insisted that it was unchosen: “The homosexual has no choice as regards his or her sexual object” (329, italics in original). See also J Fort, CM Steiner, and F Conrad, “Attitudes of mental health professionals toward homosexuality and its treatment,” in HM Ruitenbeck, editor, Homosexuality: A changing picture (London: Souvenir Press, 1966), 157–158.

[30] Gerald C. Davison, “Homosexuality: The Ethical Challenge,” presidential address to eighth Annual Convention of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Chicago, 2 November 1974; published in Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 44/2 (1976): 157–162; Charles Silverstein, “Homosexuality and the Ethics of Behavioral Intervention,” Journal of Homosexuality 2/3 (1977): 205–211.

Then why did the researchers want to “change” gay people?

Researchers realized that homosexual behavior carried a huge burden and stigma in the culture of the time. They wanted to relieve suffering. Researchers frequently emphasized that they would only treat those who expressed a desire to change their feelings and/or behavior.[31] Some of their patients were married men, and the clinicians wished to help solve the problem that homosexual activity was causing in the marriage.[32]

Behaviorists objected to efforts to force the unwilling into therapy, and many regarded those sent to “treatment” as an alternative to being jailed for violating sodomy laws as unlikely to be successful.[33]

[31] G. Terence Wilson and Gerald C. Davison, “Behavior Therapy and Homosexuality: A Critical Perspective,” Behavior Therapy 5 (1974): 25; Lynn P. Rhem and Ronald H. Rozensky, “Multiple behavior therapy techniques with a homosexual client: a case study,” Journal of Behavioral, Therapeutic & Experimental Psychiatry 5 (1974): 54; Ronald W. Field, “Book Reviews: A Neo-Pavlovian View of Behaviour Therapy: Tape 2-Aversion Therapy of Homosexuality,” in Medical Journal of Australia (20 September 1975): 489; Ward Houser, “Aversion therapy,” in The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, edited by Wayne R. Dynes, Routledge Revivals edition (Gardland Publishing, Inc: New York & London, 1990), 101.

[32] Donald E. Larson, “An adaptation of the Feldman and MacCulloch approach to treatment of homosexuality by the application of anticipatory avoidance learning,” Behavioral Research and Therapy 8 (1970): 210; N[athaniel] McConaghy, “Subjective and Penile Plethysmograph Responses to Aversion Therapy for Homosexuality: A Follow-up Study,” British Journal of Psychiatry (1970), 560; Lee Birk, William Huddleston, Elizabeth Miller, and Bertram Colder, “Avoidance Conditioning for Homosexuality,” Archives of General Psychiatry 25 (October 1971): 317–318.

[33] Kurt Freund, “Some problems in the treatment of homosexuality,” in Hans Jurgen Eysenck, editor, Behaviour Therapy and the Neuroses: Readings in Modern Methods of Treatment Derived from Learning Theory (Symposium Publications Division, Pergamon Press, 1960), 312-326.

Scientific work before 1970

When was homosexuality first treated with aversion therapy?

Electric shock was first used as an aversive therapy for homosexuality in 1935.[34] This use of aversion does not seem to have been explored much further until the 1960s. An influential early report was Kurt Freund’s 1960 paper, which reported the use of caffeine and apomorphine as an aversive stimulus.[35] (Apomorphine is a non-addictive drug that induces severe nausea.) Freund treated sixty-seven homosexuals with classical aversive conditioning using this method. Twenty patients were there for court-ordered treatment, and only three of these had any improvement at all. Of the remaining forty-seven, after three years 12 [~25%] had shown some long-term heterosexual change. A second follow up two years later found even lower success rates: three had returned to homosexual behavior, and many of the others did not find women other than their wives sexually attractive.[36]

Freund’s lack of success was noted in the research literature. In 1969, a review of aversion therapy data noted that “Clearly these results [of Freund in 1960] do not encourage an attitude of optimism either to the use of chemical aversion or to a classical conditioning approach.”[37]

[34] LW Max, “Breaking up a homosexual fixation by the conditional reaction technique: A case study,” Psychological Bulletin 32 (1935): 734.

[35] Kurt Freund, “Some problems,” 312–326.

[36] MP Feldman, “Aversion Therapy of Sexual Deviations: A critical review,” Psychological Bulletin 65/2 (February 1966): 67.

[37] MP Feldman, “Aversion Therapy of Sexual Deviations: A critical review,” 67.

What’s the difference between “classical” and “operant” conditioning?

“Classical conditioning” refers to involuntary responses—Pavlov’s drooling dog was the first, classic example. The dog did not “choose” to salivate when a bell was rung. Its body had simply learned to associate the bell with food, and salivated automatically.

“Operant conditioning” was a more sophisticated concept, in which the animal or person would be either punished or rewarded for taking certain actions. The general failure of Freund’s classical conditioning approach meant that future researchers focused on operant approaches. A dog could be trained to do a trick by giving him food whenever he performed. The dog would learn that it would be fed if he did the trick, and so choose to do so.

Was nausea therapy tried any further?

In 1962, Basil James described the general failure of psychodynamic treatment, underlining “the feeling of therapeutic impotence which the practitioner so often feels when faced with the problem of homosexuality.”[38] He described a single case study of a Kinsey 6 (i.e., “exclusively homosexual”) patient using apomorphine.

The patient was “skeptical,” but he demonstrated a remarkable change. He “has felt no attraction at all to the same sex since the treatment, whereas previously this attraction had been present throughout every day. Sexual fantasy is entirely heterosexual and he soon acquired a regular girl friend.”[39] James was enthusiastic about the possibilities:

The [aversion] treatment is brief, is in no way analytical, and can be adapted to the individual patient. Although the period of follow-up is comparatively short, the patient’s heterosexual attraction is increasing with time rather than decreasing, and it would be easy to give a “booster” course of treatment should he show signs of relapse. The method depends very largely on the co-operation of the patient and his desire to be rid of his homosexual feelings. In his case other methods of treatment had completely failed.[40]

[38] Basil James, “Case of Homosexuality Treated by Aversion Therapy,” British Medical Journal (17 March 1962): 768.

[39] James, “Case of Homosexuality,” 768.

[40] James, “Case of Homosexuality,” 770.

What about electric shocks?

The use of nausea as the negative stimulus had several disadvantages. It was difficult to control precisely—one had to administer the drug and then wait for its effect, so an immediate, repeated reward or punishment as needed for operant conditioning was not possible.[41]

The strength of the nausea could also vary from patient to patient.[42] Vomiting was obviously very unpleasant for the patient, and the psychiatric hospital nurses and other professionals would not have enjoyed it either.[43]

Electrical shock had been used in animals and humans previously, and was an attractive alternative “because it is safe, is less unpleasant for the patient and allows easier timing of conditional and unconditional stimuli. It also allows the use of operant conditioning schedules in place of the classical method. With these modifications it has proved possible to produce improvement of certain symptoms without causing undue distress to the patient.”[44] From the early 1960s onward, this was the aversive stimulus of choice.[45]

[41] See discussion in JG Thorpe, E Schmidt, and D Castell, “A Comparison of Positive and Negative (Aversive) Conditioning in the Treatment of Homosexuality,” Behavior Research and Therapy 1/2–4 (1963): 357; Edward J. Callahax and Harold Leitenberg, “Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: contingent shock and covert sensitization,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 81/1 (1973): 60–61.

[42] John Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behaviour: Modification and Assessment (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 34–35.

[43] “Chemical [i.e., nausea-causing] aversion is highly unpleasant, not only for the patient but also for the therapist and the nursing staff,” (MP Feldman, “Aversion Therapy of Sexual Deviations: A critical review,” Psychological Bulletin 65/2 (February 1966): 77). “The treatment is unpleasant, not only for the patient, but also for the therapist and the nursing staff. It is not uncommon for attendants to object to participating in this form of treatment and there can be no doubt that it arouses antagonism in some members of the hospital staff. Complaints about the method being unaesthetic and even harrowing are not entirely without justification—it is certainly a method which does not lend itself to popularity. The unpleasant nature of this treatment also makes it rather difficult to arrange for patients to be treated on an out-patient basis” (S Rachman, “Aversion therapy: Chemical or electrical?” Behavioral Research and Therapy 2/2-4 (1964): 289–299.)

[44] Isaac M. Marks and Michael G. Gelder, “Transvestism and Fetishism: Clinical and Psychological Changes during Faradic Aversion,” British Journal of Psychiatry 113 (1967): 711-729.

[45] John Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behaviour: Modification and Assessment (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 35.

I’ve seen electric shock therapy on TV, and it doesn’t look mild! It looks very unpleasant.

It is important to distinguish between two uses of electricity in psychiatry. The first is “electroconvulsive therapy” (ECT). This was the use of electricity to treat psychiatric disorders by causing a seizure. It is well-studied, and quite effective. It continues to have an important role in psychiatry.[46] TV and movies have given many a distorted idea of the process: we often see the hero strapped down by a villain, given a stick or leather strap to bite on, and then the application of massive doses of electricity as he writhes in pain and convulses violently.

This is not at all realistic. Instead, the patient is put into brief anesthesia and given a muscle paralytic. The shock is applied, but the patient is not aware of it, and does not physically convulse or thrash around. They are then wakened from anesthesia.

The treatment being discussed here is completely different. It involves the use of mild, low-current shocks to a wrist or leg, like a “zap” from touching a battery with wet fingers. We will discuss the precise details as we go along.

[46] See Harold A. Sackeim, “Modern Electroconvulsive Therapy: Vastly Improved yet Greatly Underused,” JAMA Psychiatry 74/8 (August 2017): 779-780.

Was there follow-up to James’ case study?

Yes. A year later, Thorpe and colleagues began using electricity instead of nausea-producing drugs. At first, the researchers encouraged the patient to masturbate to female pictures, hoping that females would become associated with the “reward” of orgasm.

This was unsuccessful, and so the researchers then used a new technique—they added “aversive” responses with an “electric grid” upon which the patient stood in bare feet, which would deliver “a painful electric shock” when the patient was exposed to nude male pictures.[47] Eight months later, the patient still reported only occasional homosexual acts, and much more heterosexual functioning.

The authors concluded by pointing out how poorly aversion therapy had worked for alcoholics, but “the position with regard to homosexuals would appear to be far more promising.”[48]

[47] Thrope et al., 358–359.

[48] Thrope et al., 362.

These are awfully small “studies”—only a single patient!

Yes, and the small samples sizes was to be a serious problem in all of this research.

Nevertheless, work continued. In 1965 a researcher reported success with a small portable “zapper” that a drug-addicted patient could use on themselves at home—but once again this was a single patient.[49]

A more significant effort was reported by Schmidt et al. in the same year. They treated a variety of behavioral issues, but their largest group of patients were homosexuals. There were three different treatments offered: negative reinforcement (shock), positive reinforcement, and a third group who received both.

Practicing homosexuals largely declined treatment. Those who regarded “themselves to be homosexuals and feel attracted to men but who have never really indulged in homosexual practices,” all agreed to participate. (The higher success with non-practicing homosexuals could have suggested to researchers that more engrained behavior was more difficult to change, since sexual desires had been repeatedly reinforced positively by the pleasures of sex.)

The study was significantly weakened by its decision to mix homosexuals (8 patients), phobias (2), alcoholism (1), and transvestitism (1). The researchers combined those who agreed to continue, and found over all that 83% had “marked improvement” and the rest “moderate.” (Of the homosexual group, 7 were marked and 1 moderate.[50]) Longer term results were encouraging, though their optimistic conclusions are weakened by some patients not being contacted for follow-up. Most importantly, they concluded that combined negative and positive reinforcement were best.[51]

[49] Joseph Wolpe, “Conditioned Inhibition of Craving in Drug Addiction: a pilot experiment,” Behavioral Research and Therapy 3 (April 1965): 285-288.

[50] Elsa Schmidt, David Castell, and Paul Brown, “A retrospective study of 42 cases of behaviour therapy,” Behavioral Research and Therapy 3 (1965): 12–14.

[51] Schmidt et al., 18.

Were there any bigger studies?

Yes. A landmark 1967 study was the largest and best so far. It focused only on homosexuality and included 43 patients. Its design would be hugely influential and would be duplicated repeatedly.

In this case, the patient was exposed to either nude male or female slides. If he delayed too long in “dismissing” the male slides, he would receive a shock. For “positive” reinforcement, a female slide would appear after the male slide was dismissed.[52]

The researchers enthused that their success rate of around 60% was far better than anything demonstrated by psychodynamic therapy (27% at most). They believed that this was “mainly due to the use of an aversion therapy technique which has been carefully designed to make the most effective use of the findings of the experimental psychology of learning.”[53] The same authors argued elsewhere that personality factors could also predict success with their method: “We conclude that it is now possible to select homosexual patients who have a good prognosis for anticipatory avoidance aversion therapy.”[54]

[52] MJ MacCulloch and MP Feldman, “Aversion Therapy in Management of 43 Homosexuals,” British Medical Journal 2 (1967): 594.

[53] MacCulloch and Feldman, 597.

[54] MJ MacCulloch and MP Feldman, “Personality and the Treatment of Homosexuality,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 43/3 (1967): 300–317.

What kind of shocks were being used?

At this point, the “shock mat” seems to have been abandoned.[55] Further researchers used the technique described below.

A metal disc was hooked to a battery—usually from 6 to 12 volts DC.[56] The disc was placed either on the hand, wrist, or calf. This allowed a small shock to be delivered, typically for less than 1 second.

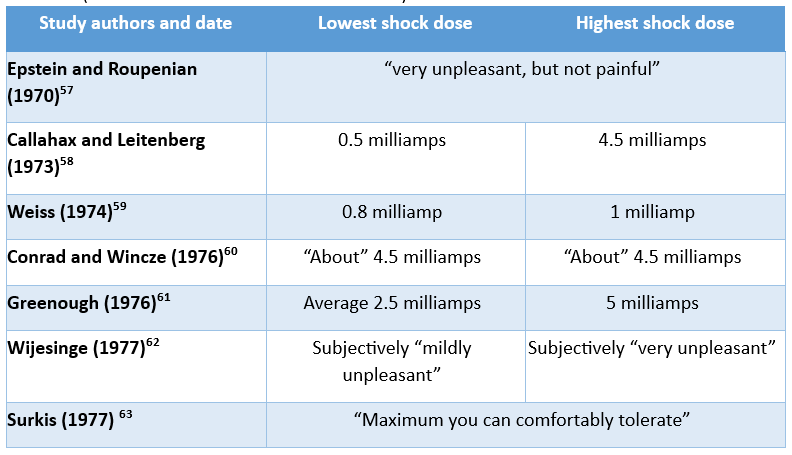

Researchers were not always careful to specify exactly how strong a shock was used. Reported numbers (not all from homosexual aversion tests) can be seen in this table:

In 1977, part of one protocol introduced subjects to the experiment like this: “the experimenter self-administered a shock at full intensity (ouch!) to demonstrate the worst that could happen, while at the same time explaining that individuals have different tolerances to electricity, and what one may not feel, another may find painful.” Subjects were told to “set the shock intensity for the maximum that you can comfortably tolerate.” [64]

(D. Michael Quinn claimed that shocks were done with “1,600 volt[s] to the client’s arm for eight seconds.”[65] As is his wont,[66] Quinn included a voluminous footnote—however, none of the cited works say anything like this. Given Quinn’s frequent misrepresentation of the evidence in service of his ideological agenda, and the intense critique which this work has received from both member and non-member reviewers,[67] this claim should be regarded as suspect unless specific evidence is provided.)

[55] Thorpe et al., “A Comparison of Positive and Negative (Aversive) Conditioning,” 360.

[56] MP Feldman, MJ MacCulloch, JF Orford, and V Mellor, “The Application of Anticipatory Avoidance Learning to the Treatment of Homosexuality,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 45/2 (June 1969): 114; B. Wijesinge,”Massed aversion treatment of sexual deviance,” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 8/2 (1977): 135–137;

[57] Seymour Epstein and Armen Roupenian, “Heart rate and skin conductance during experimentally induced anxiety: The effect of uncertainty about receiving a noxious stimulus,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 16/1 (September 1970): 21.

[58] Edward J. Callahax and Harold Leitenberg, “Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: contingent shock and covert sensitization,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 81/1 (1973): 70.

[59] Leslie Ellin Bloch Weiss, “An Exploratory Investigation of Aversion-Relief Paradigms with Human Subjects,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawaii, 1974, 52.

[60] Stanley R. Conrad and John P. Wincze, “Orgasmic Reconditioning: A Controlled Study of Its Effects upon the Sexual Arousal and Behavior of Adult Male Homosexuals,” Behavior Therapy 7 (1976): 159.

[61] Timothy John Greenough, “An Analogue Study of Specific Parameters of Overt and Covert Aversive Conditioning,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Western Ontario, February 1976.

[62] B. Wijesinge,”Massed aversion treatment of sexual deviance,” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 8/2 (1977): 135.

[63] Herman Surkis, “The modification of smoking behaviour: a research evaluation of aversion therapy, hypnotherapy, and a combined technique,” master’s thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, May 1977, 47.

[64] Surkis, 47.

[65] D. Michael Quinn, Same-Sex Dynamics Among Nineteenth-Century Americans: A Mormon Example (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 379.

[66] A non-LDS discussion of Quinn’s tendency to “overdocumentation” is in Stephen J. Stein, “Reviewed Work: SameSex Dynamics among Nineteenth-Century Americans: A Mormon Example by D. Michael Quinn,” Church History 67/2 [June 1998]: 420–422. LDS reviewers have long noted the same tendency: Duane Boyce, “”A Betrayal of Trust,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 9/2 (1997), 147–151, 162–16; William J. Hamblin, “That Old Black Magic,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011,” 12/2 (2000): 227n5, 245–246.

[67] George L. Mitton and Rhett S. James, “A Response to D. Michael Quinn’s Homosexual Distortion of Latter-day Saint History,” FARMS Review of Books 10/1 (1998): 141–263; Klaus J. Hansen, “Quinnspeak,” FARMS Review of Books 10/1 (1998): 132–140; Vella Neil Evans, Women’s Studies, University of Utah, at the Sunstone Symposium, Salt Lake City, t6 August 1996. Audio Tape No. 238; cited by Mitton and James,195n129; Bryan C. Short, review of “Same-Sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-Century Americans: A Mormon Example,” Christian Century 114/2 (15 January 1997): 56–58 and Peter Boag, “‘Behind the Zion Curtain’ Homosexuals and Homosexuality in the Historic and Contemporary Mormon-Cultural Region: A Review Essay,” New Mexico Historical Review (1 July 1997): 259–266; Gregory L. Smith, “Feet of Clay: Queer Theory and the Church of Jesus Christ [review of Taylor G. Petrey, Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 43 (2021): 113– 125, 251–261, and note 9 for these references.

So . . . how much electric current is that?

It is important to remember that both electrical wires were placed on the same body part. As a result, the electrical current did not flow through the entire body (it would be important to avoid electricity to the heart, for example). There was a local effect only.

The Electronic Library of Construction Occupational Safety describes one second at 1 milliamp as “just a faint tingle,” and 5 milliamps as “slight shock felt. Disturbing, but not painful … strong involuntary [muscle] movements can cause injuries.”[68] (The duration of shock in the BYU experiment was 0.5 second.[69]) Tissue burns happen at 5,000 milliamps.[70]

Compare to TENS machine

For context, consider a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machine. These devices apply an electrical current to muscles or other tissues to help with pain relief. As with the aversion therapy, the electrical current does not pass through the whole body, but only to a limited area because the electrical leads are close together.

One present-day clinic describes the voltages involved:

The amount of energy you receive from an electric current is determined by the amps times the volts times the time. TENS units use only a very small number of amps. In a typical unit, the settings don’t go higher than 100 mA. Your house current reaches your breaker box with a current of up to 220 A, or 220,000 mA, and each circuit in your house may have a circuit breaker that will usually trip at about 15-20A. This means that for the same amount of time, a TENS machine will expose you to less than 1/1000 the amount of energy a house current does before a breaker trips.

In other words, a TENS pulse delivers a small amount of energy, making it a safe level of current. If it’s set too high, you might experience some mild discomfort, but you won’t be injured before you have time to adjust TENS to a more comfortable level.[71]

TENS machines tend to deliver pulses of 100 microseconds, while aversion therapy experiments were typically around a second or less. But given that TENS machines provide between 20 and 100x the electrical current of aversion therapy, it is difficult to see it as either dangerous or injurious, particularly when the client gets to choose the voltage, and is free to discontinue the experiment if he wishes.

What were the ethics of using a small shock?

Researchers were aware that, slight as it was, electric shock might still disturb some of their audience on ethical grounds. One group replied:

A final argument pertains to the possible ethical undesirability of a treatment which involves inflicting electric shocks—albeit from low voltage batteries. Two points may be made in reply. First, the patients are the best judges as to which is more bearable—the considerable distress which many feel as a consequence of their homosexual orientation, or a short period of weeks, for perhaps 12 hours of which they are in receipt of a number of electric shocks. Of our total of 73 patients, 63 completed their courses of aversion treatment. Second, the therapist now has the ability to predict the likelihood of success.[72]

This stance would anticipate the later debates about how “freely” homosexuals were choosing therapy at all (discussed below).[73]

Discussions about medical ethics generally presuppose that a treatment is of some potential benefit. It is common in medical settings to speak of a ” benefit/risk ” ratio. No treatment is without risk. To decide whether a given treatment should be offered or accepted, participants assess the likelihood that the treatment will benefit the patient versus its likelihood of harm. If the “ratio” is greater than one, the treatment is probably a good choice.[74] (The many serious side effects of chemotherapy, for example, are still considered acceptable because the benefit of treatment may be not dying of cancer. Offering the same potentially deadly medications to treat a hangnail would be a much different proposition.)

If a treatment is ineffective, then the benefit is always zero—and the benefit/risk ratio will always be zero. (Zero benefit divided by any risk at all is still zero.) From this perspective, given what we know today about the failure of aversion therapy and other conversion therapies to achieve their goals, offering them is ethically inappropriate.[75]

During this 1960s–1970s, however, some evidence suggested that the treatment was successful—and as in the above case, efforts were underway to better understood who was likely to be helped.

Were there any other challenges to using shock?

Above all else, individual variation was the biggest challenge:

Individuals also vary enormously in the amount of shock they can tolerate. It is a common experience to find that one patient will be exceedingly sensitive even at the lowest setting of the shock-box, whereas the next will find the maximum shock hardly painful. It is not technically easy to produce a. safe shock-box which will be predictably strong enough for all subjects, particularly in view of the considerable tolerance to shock that can develop during the course of treatment. Some of this variation may be due to the changes in pain threshold brought about by changes in the level of anxiety.76]

[68] Center for Construction Research and Training, “Dangers of Electrical Shock,” Electronic Library of Construction Occupational Safety (accessed 17 January 2022), https://www.elcosh.org/document/1624/888/d000543/section2.html.

[69] See note 153.

[70] CDC Workplace Safety and Health, Electrical Safety: Safety and Health for Electrical Trades – Student manual (Department of Health and Human Services, USA, publication No. 2002-123), 6, https://www.elcosh.org/record/document/1624/d000543.pdf

[71] TMJ Therapy and Sleep Center of Colorado, “How the Current In TENS Compares to Your House Current,” webpage (accessed 15 January 2022), https://www.tmjtherapyandsleepcenter.com/blog/current-tens-compares-housecurrent/

[72] MI MacCulloch, CJ Birtles, and MP Feldman, “Anticipatory Avoidance Learning for the Treatment of Homosexuality: Recent Developments and an Automatic Aversion Therapy System,” Behavior Therapy 2 (1971):157–158.

[73] See notes 126–136.

[74] Anoop Kumar, “Risk and benefit analysis of medicines,” Journal of International Medical Research 48/1 (2018): 1– 2; Filip Mussen, Sam Salek, and Stuart Walker, “A quantitative approach to benefit-risk assessment of medicines – part 1: the development of a new model using multi-criteria decision analysis,” Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 16/S1 (1 June 2007): S2–S15. The same principles apply to other interventions, such as the decision to image a child with radiation: Sjirk J. Westra, “The communication of the radiation risk from CT in relation to its clinical benefit in the era of personalized medicine-Part 2: benefits versus risk of CT,” Pediatric Radiology 44 (2014): 525– 533.

[75] American Psychiatric Association, “APA Reiterates Strong Opposition to Conversion Therapy,” (15 November 2018), https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news–releases/apa–reiterates–strong–opposition–to–conversiontherapy. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, “Conversion therapy,” (February 2018), https://www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2018/Conversion_Therapy.aspx. For the Church’s current position opposing conversion therapy, see: “Official Statement: Church Continues to Oppose Conversion Therapy,” newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org (25 October 2019),

https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/statement-proposed-rule-sexual-orientation-gender-identitychange..

[76] John Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behaviour: Modification and Assessment (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 41.

By the end of the 1960s, where were we?

A review of aversion therapy for all undesired sexual behaviors concluded:

The great majority of aversion therapists have used classical conditioning, that is, the attempt is made to associate anxiety or fear with the previously attractive homosexual stimulus. Only a small minority have used instrumental conditioning, in which the avoidance or escape from the punishing stimulus is contingent on the performance of a specific operant response—generally the avoidance of the previously attractive stimulus.[77]

Classical conditioning was out; operant conditioning was in.

The decade concluded with on-going enthusiasm. For example, successful use in transvestitism and fetishism,[78] other sexual “deviations,”[79] encouraged on-going hopes. An important theoretical paper by Feldman et al. allowed others to duplicate their methods. The authors were particularly keen on the ability to record the readings and responses of patients. Behaviorism was all about gathering data.[80]

Another pilot study captures the mood well:

Until recently it was a widely held opinion that little could be done to alter the sexual orientation of homosexuals (Curran and Parr, 1957). Most therapists confined their efforts to helping the homosexual to adjust to his role. Now opinions are beginning to change. Bieber et al. (1962) with psychoanalysis and MacCulloch and Feldman (1967) with aversion therapy have reported a significant number of successes—where homosexual orientation has been lost and heterosexual orientation gained. There is no shortage of patients who seek such a transformation and who suffer in one way or another from their homosexual role. It is becoming increasingly clear that in these patients the term homosexuality covers a range of clinical problems, some of which will be resistant to such therapeutic attempts, and some of which will respond satisfactorily. But as yet we are largely ignorant of the factors which decide such outcomes. …

Further justification for continued effort comes from the results achieved by MacCulloch and Feldman (1967). These workers reported a 57 per cent. success rate in 43 homosexuals treated by electric aversion. Although direct comparison with their results is not possible, there is little doubt that their results are superior to those reported here.[81]

[77] Feldman, “Aversion Therapy of Sexual Deviations,” 61.

[78] Isaac M. Marks and Michael G. Gelder, “Transvestism and Fetishism: Clinical and Psychological Changes during Faradic Aversion,” British Journal of Psychiatry 113 (1967): 711–729.

[79] MP Feldman, MJ MacCulloch, Mary L. MacCulloch, “The Aversion Therapy Treatment of a Heterogeneous Group of Five Cases of Sexual Deviation,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 44 (1968): 113–124

[80] MP Feldman, MJ MacCulloch, JF Orford, and V Mellor, “The Application of Anticipatory Avoidance Learning to the Treatment of Homosexuality,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 45/2 (June 1969): 109–117.

[81] John Bancroft, “Aversion Therapy of Homosexuality: A pilot study of 10 cases,” British Journal of Psychiatry 115 (1969): 1418, 1428.

The 1970s

The 1970s saw enormous changes in how psychiatry and psychology regarded homosexuality. The American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality per se from their list of official diseases in 1973. At the same time, there remained enthusiasm for aversive therapy for those who were dissatisfied with their homosexual inclinations.

How did research techniques change?

Behaviorists were keen on objective data, and so there was an effort to use standard scales to assess sexual desires pre- and post-treatment. The 1970s also saw the introduction of the “plethysmograph,”—this was something like a small blood pressure cuff.[82] It was placed around the penis to measure the degree of sexual excitement, since it was believed that this might more accurately reflect the patient’s “true” state than self-report.[83]

[82] Bancroft has an appendix with detailed images, descriptions, and data traces in Deviant Sexual Behavior, 227–233.

[83] Edward J. Callahax and Harold Leitenberg, “Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: contingent shock and covert sensitization,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 81/1 (1973): 60–73; Timothy John Greenough, “An Analogue Study of Specific Parameters of Overt and Covert Aversive Conditioning,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Western Ontario, February 1976.

What did researchers think about the evidence for aversion therapy?

Researchers are rarely in universal agreement, and this was true in the early 1970s. A brief look at some of the published conclusions shows the growing confidence in aversion methods:

McConaghy (1970)

Value of aversive treatment. Though at follow-up only seven patients in the present study considered that their sexual orientation had changed from predominantly homosexual to predominantly heterosexual, it is considered that other criteria of evaluating response are also important. Some patients who remained exclusively homosexual reported that they were no longer continuously preoccupied with homosexual thoughts and felt more emotionally stable and able to live and work more effectively. Others were able to control compulsions to make homosexual contacts in public lavatories, which had caused them to be arrested one or more times previously. Of the nine married men who presented at follow-up, six stated their marital sexual relationship had markedly improved. This included two of the three who had ceased having intercourse with their wives some years before treatment. It was concluded that of the 35 whose subjective reports were accepted at follow-up, 10 patients showed marked, 15 some and ten no improvement.[84]

Ph.D. dissertation (1971)

Thorpe, Schmidt, Brown and Castell (1964) reported encouraging results of an aversion relief therapy procedure which they used in treatment of homosexuality, phobias and obsessive-compulsive behavior.[85]

Callahax and Leitenberg (1973)

A comparison of shock aversion therapy to standard therapy and a negative imagery technique showed “no substantial difference.” Rather than conclude that perhaps none of the techniques were of much value, they concluded: “in general … both treatments combined led to a favorable outcome.”[86]

Tanner (1973)

Tanner used low (2.5 milliamp) and high (5 milliamp) shocks and found the latter more effective. This likely increased the belief that a genuine effect was being studied.[87]

In the same year, Tanner would write, “There is more evidence of its effectiveness in modifying homosexual behavior than there is of any other mode of treatment.”[88]

[84] McConaghy, “Subjective and Penile Plethysmograph,” 117, 555–560.

[85] Beatrice Ila Scheinbaum Manno, “Weight reduction as a function of the timing of reinforcement in a covert aversive conditioning paradigm,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, 1971, 18.

[86] Edward J. Callahax and Harold Leitenberg, “Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: contingent shock and covert sensitization,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 81/1 (1973): 73.

[87] Barry A. Tanner, “Shock Intensity and Fear of Shock in the Modification of Homosexual Behavior in Males by Avoidance Learning,” Behavior Research and Therapy 11 (1973): 213–218.

[88] Barry A. Tanner, “Aversive shock issues: Physical danger, emotional harm, effectiveness and ‘dehumanization’,” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 4 (1973): 113–116.

Were there no skeptics in the early 1970s?

Yes. Some researchers believed that the techniques were working, but that the reasons given were mistaken:

aversion therapy aimed at eliminating sexual deviation is increasingly advocated as the treatment of choice, due in part to the growing application of the experimental behavioral sciences to the clinic and in part to the relative success of this technique compared to psychoanalytic psychotherapy.[89]

The author went on to question whether claims about “aversion relief” were adding anything to the “aversion therapy” and highlighted the need for more research:

in view of the well-documented observation that heterosexual responsiveness increases during aversion therapy in the absence of any attempt to accomplish this goal, all clinical reports that aversion relief is effective are suspect since aversion relief has never been used in the absence of aversion therapy to isolate treatment effects. … The observation noted independently by several investigators that aversive techniques alone set the occasion for rises in heterosexual responsiveness is a paradoxical and puzzling phenomenon worthy of further investigation.[90]

Even if researchers did not believe the evidence was adequate to claim that aversion therapy worked, that does not mean that they would have seen further work as illegitimate. One of the most challenging parts of medical research can be proving that a treatment does not work. A lack of adequate evidence might simply mean that more studies were needed to answer the question more definitively.

[89] David H. Barlow, “Increasing Heterosexual Responsiveness in the Treatment of Sexual Deviation: A Review of the Clinical and Experimental Evidence’,” Behavior Therapy 4 (1973): 656.

[90] David H. Barlow, “Increasing Heterosexual Responsiveness in the Treatment of Sexual Deviation: A Review of the Clinical and Experimental Evidence’,” Behavior Therapy 4 (1973): 659, 667.

Anyone who didn’t think that it didn’t work at all?

Yes. There were some who argued against the techniques altogether. As early as 1964, some regarded it as cruel and harsh.[91]

Charles Silverstein, a gay therapist, was a staunch opponent of any attempt to treat homosexuality as anything but a benign and normal behavior.

He would later insist that anyone working with patients to change orientation was in a “sadomasochistic relationship,” while aversion therapists were guilty of “violence in the name of science.” Even psychoanalysis was said to be “primarily the acting out of the sadomasochism of both parties.” He dismissed any reports of successful change as “probably based on a rather small sample of homosexual masochists.”[92]

(There is irony in Silverstein’s complaint that pathologizing homosexuality is a way of delegitimizing gay sex via psychiatry’s cultural authority, while smearing all his opponents with the psychiatric construct of “sadomasochism” to delegitimize them.)

Looking back in 2007, Silverstein was less critical of those involved in the research:

I did not consider these men, most of whom made their reputations in aversion therapy or psychoanalysis, cruel. They were diligent in their attempt to find the holy grail of treatment that would change a person’s sexual orientation, and they were motivated by a sincere desire to help.[93]

[91] FA Whitlock, “Correspondence,” British Medical Journal (15 February 1964):437 (Note that another correspondent, Clifford Allen, praised the same technique as “a harmless and useful method of aversion therapy … [that] should be of great use for outpatients” on the same page.)

[92] Charles Silverstein, “Homosexuality and the Ethics of Behavioral Intervention,” Journal of Homosexuality 2/3 (1977): 208.

[93] Charles Silverstein, “Wearing Two Hats: The Psychologist as Activist and Therapist,” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy 11/3–4 (2007): 25.

1973 and the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

Homosexual rights groups had long resented psychiatry’s label of their sexual preferences as an illness.[94] In the early 1970s, they began a concerted campaign to get this changed.

We can sympathize with their position, and even agree that it resulted in the proper course of action—labeling homosexual orientation a “mental illness” is unwise.

To understand the period, however, we must understand that this change was largely brought about through agitation and political pressure. It was not the result of a sober assessment of the scientific evidence. As one gay historian noted, it was the result of

a sustained campaign of protests by lesbian and gay activists at APA conferences and meetings throughout the early 1970s, with the collaboration of closeted psychiatrists within the APA. …

Using “guerrilla theater tactics and more straightforward shouting matches,” they denounced psychiatrists who advocated and practiced aversion therapy. …

Over the course of four years, the protesters followed the APA from annual meeting to annual meeting around the country. As they did so, their strategies shifted from disruption and denunciation to appropriation and inclusion, and the range of key actors involved diversified as they were aided by conference organizers and sympathetic psychiatrists within the APA, including a closeted group of high-ranking members who called themselves the “GAYPA.”[95]

[94] Silverstein, “Wearing Two Hats,” 10, 15–17.

[95] Geeti Das, “Mostly Normal: American Psychiatric Taxonomy, Sexuality, and Neoliberal Mechanisms of Exclusion,” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 13 (2016): 390–393.

But science still won the day, right?

Many did not believe so, and in retrospect it is hard to see the decision as scientific (though it accords with what we know now).

The recommendation to remove homosexuality from the manual (called the DSM-II) was written by Robert Spitzer. In Spitzer’s account, this was not a case where the data convinced him. Instead, he made the decision on emotional grounds:

[he] met an activist who took him to a clandestine after-party where he witnessed a psychiatrist burst into tears at being in a space for gay psychiatrists for the first time. Stunned at the sudden outing of many familiar faces, and avowedly moved by sympathy, he decided to draft the resolution for depathologization immediately.[96]

Again, we can admire Spitzer’s humanitarian instincts, and even conclude that the decision was right, though not reached via science: “Spitzer … came to see these individuals as underdogs and as being in pain, and decided that he wanted to help them.”[97]

But to understand this period, we cannot miss the fact that this decision was being made on political and emotional grounds—not purely scientific ones. (Some pointed out that Spitzer himself had no publication record on matters of sexuality.[98]) That made the decision questionable to many, and it stirred an enormous debate within psychiatry. Spitzer’s camp narrowly won, but that does not mean that there was a scientific consensus.

Those who believed, on what they believed was a scientific basis, that homosexuality was pathological were not persuaded. To those with philosophical or religious opposition to homosexual acts, it appeared to be the imposition of one philosophical view over another:

Those who opposed the removal of homosexuality from DSM-II argued that it was the civil rights issue rather than the logic of Spitzer’s position that was uppermost in the minds of those who had voted in favor …. politically liberal psychiatrists had allowed their social values to interfere with their scientific judgment.[99]

“We wanted,” wrote Silverstein in 2007, “the whole house of moral cards to collapse so that all forms of variant sexuality would be acceptable. … We reasoned that the psychiatric professions were ‘gatekeepers’ of society’s attitude toward sexuality. Change their minds about variant forms of sexuality, and the rest of society … would fall in step.”[100]

This radical agenda was all too clear to those who disagreed with Spitzer’s motion.

[96] Geeti Das, “Mostly Normal: American Psychiatric Taxonomy, Sexuality, and Neoliberal Mechanisms of Exclusion,” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 13 (2016): 393.

[97] Peter Zachar and Kenneth S. Kendler, “The removal of pluto from the class of planets and homosexuality from the class of psychiatric disorders: a comparison,” Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 7/4 (2012): 3, http://www.peh-med.com/content/7/1/4.

[98] Charles W. Socarides, “Scientific Politics and Scientific Logic: The Issue of Homosexuality,” Journal of Psychiatry 19/3 (Winter 1992): 310.

[99] Ronald Bayer, Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1987), 148.

[100] Silverstein, “Wearing Two Hats,” 17.

Aren’t all such decisions influenced by non-scientific factors?

Absolutely—no such decision is entirely free of human politics and emotion, but this one involved those factors more than most. Two historians who agreed with the decision nevertheless noted:

The controversies over psychiatric classification in the past 30 years have garnered considerable attention. The existence of rancorous debates about how to classify is associated with claims that the developers of psychiatric diagnostic systems inappropriately clothe themselves in the aura of science without being scientific.

… many psychiatrists vilified the decision on homosexuality as scientifically unsound, harmful to legitimate patients, immoral, politically motivated and a concession to the mob. Comparisons with dogmatic pronouncements of church councils were made as well. … [There] was a sentiment among some conservative psychiatrists that not just the profession, but also morality and civilization itself, had been betrayed.[101]

One analyst wrote later of how criticism of those who did not agree “w[as] augmented by hatefilled letters, threatening attacks over the telephone, and even threats of terrorist action against those who continued to speak of their scientific findings.”[102]

Silverstein would later argue: “‘truth’ is irrelevant in explaining social advances, as they are determined by politics. Politics is power and power determines truth as well as its companion, goodness.”[103] A good example of this attitude is Silverstein’s account of the term “homophobia”:

The first step in developing a new theoretical model was the invention and propagation of the term “homophobia,” the feelings of aversion some people feel toward homosexuals. This term was quickly adopted and was a brilliant strategy of name-calling by the gay community. If we suffered from “homosexuality,” they suffered from “homophobia.” The political use of the term quickly spread to academia.[104]

[101] Peter Zachar and Kenneth S. Kendler, “The removal of Pluto from the class of planets and homosexuality from the class of psychiatric disorders: a comparison,” Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 7/4 (2012), 1, 4, http://www.peh-med.com/content/7/1/4.

[102] Charles W. Socarides, “Scientific Politics and Scientific Logic: The Issue of Homosexuality,” Journal of Psychiatry 19/3 (Winter 1992): 310.

[103] Silverstein, “Wearing Two Hats,” 17.

[104] Silverstein, “Wearing Two Hats,” 23.

Do we have any sense what the majority of psychiatrists believed?

There was a vote by the membership that sustained the decision—but only a minority voted. Letters from the APA presidential candidates were sent encouraging psychiatrists to vote in favor, though activists hid that the letter was written and its mailing financed by the National Gay Task Force, a political pressure group.[i]

In 1977—four years later—a survey was conducted to see what psychiatrists thought. “Analysis of the first 2,500 responses to a poll of 10,000 psychiatrists found that 69 percent believed that homosexuality usually represented a pathological adaptation. Only 18 percent disagreed with this proposition.”[ii]

Despite the passage of time, the majority of the profession still seemed to differ with the APA’s new policy.

[105] Ronald Bayer, Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1987), 145–146, for the aftermath see 151–157.

[106] Bayer, 167; citing “Sexual Survey #4: Current Thinking on Homosexuality,” Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality 11 (November 1977): 110–111.

Given the APA decision to no longer call it an illness, why did anyone continue to treat homosexuality?

The 1973 decision only removed homosexuality per se from the DSM-II. That is, merely having homosexual feelings or desires was not diagnostic of having a mental illness. Another diagnosis was created: Sexual Orientation Disorder (SOD)—this included those (gay or straight) who were troubled by their sexual orientation.

The intensely political nature of the APA change was also evident abroad. In Great Britain and at the World Health Organization (WHO), homosexuality was classed as an illness until 1992.[107] Arguably, in those venues, the politics operated in the opposite direction. Aversion therapy continued in “National Health Service and military hospitals throughout the UK from the 1950s to the 1980s.”[108]

In short, in 1973 (and for a long time thereafter) there was no consensus about the scientific status of homosexuality. The APA had reached an organizational decision, but it does not seem to have been shared by the majority of American psychiatrists, much less those abroad.

And, in any case, anyone troubled by their homosexuality was still eligible for treatment as SOD. Given that before 1973 most behaviorists opposed the involuntary treatment of homosexuality anyway, not much changed on the aversion therapy front.

Even a 1973 survey of therapists in the heavily-gay San Francisco area found that although 98% believed homosexuals could function normally in society, and 99% opposed criminalization of homosexual acts, 38% would be willing to help those who sought to change their sexual orientation. Less than half were unwilling to do so.[109]

Spitzer himself would study conversion therapy more generally, and as late as 2003 concluded that “the participants’ self-reports [of significant change] were, by-and-large, credible and that few elaborated self-deceptive narratives or lied. Thus, there is evidence that change in sexual orientation following some form of reparative therapy does occur in some gay men and lesbians.”[110] Complaints about weak study design would later lead him to apologize for the article.[111]

If a sympathetic observer could believe this as late as 2003, it is unsurprising that many believed similarly in the 1970s.

[107] T Dickinson, M Cook, J Playle, and C Hallett, “Nurses and subordination: a historical study of mental nurses’ perceptions on administering aversion therapy for ‘sexual deviations’,” Nursing Inquiry 2014; 21: 283.

[108] Tommy Dickinson, “Nursing history: aversion therapy,” Mental Health Practice 13/5 (February 2010): 31.

[109] Donna Aileen Coffin, “Windows in the Closet: Perspectives on Homosexuality for the helping professions,” master’s thesis, University of Arizona, 1986, 91; citing J Fort, CM Steiner, and F Conrad, “Attitudes of mental health professionals toward homosexuality and its treatment,” in HM Ruitenbeck, editor, Homosexuality: A changing picture (London: Souvenir Press, 1966), 157–158.

[110] Robert L. Spitzer, “Can some gay men and lesbians change their sexual orientation? 200 participants reporting a change from homosexual to heterosexual orientation,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32 (5), 403– 417. doi:10.1023/A: 1025647527010.

[111] Robert L. Spitzer, “Spitzer reassesses his 2003 study of reparative therapy of homosexuality,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 41/4 (2012): 757. doi:10.1007/ s10508‐012‐9966‐y. 757

BYU in the 1970s

Can you tell me about aversion therapy use at BYU in the 1970s?

Yes. Aversion therapy was used by some at BYU. We will examine one PhD. dissertation written by Max Ford McBride in 1976.

First, however, we will look at what researchers were saying about aversion therapy from the APA decision until McBride’s study. This will allow us to examine McBride’s dissertation in its time.

Following that, we will review what some have called “urban legends” about this therapy.

Scientific literature from 1974–1976

A 1974 review of the literature noted:

- “aversion therapy is the most common and preferred method of treatment of homosexual behavior, with systematic desensitization a somewhat distant second contender.”

- “We echo Bachman and Teasdale’s (1969) surprise at the considerable success Feldman and MacCulloch have achieved with the use of their … technique (the efficacy of which is further substantiated by Birk et al. 1971 study), not because of theoretical reasons relating to the specifics of the conditioning paradigm involved, but because the logic of their research paradigm precluded a behavioral analysis of the presenting problem. A more complete assessment together with the use of another technique(s) might have resulted in even greater outcome efficacy.”[112]

Thus in 1974, aversion therapy was the most common treatment method, and might even be improved upon according to these authors. That year also saw the publication of another successful case study.[113]

A textbook on the treatment of “deviant sexual behavior” was published that same year. It included an extensive review of the aversive techniques and results to date.[114] Several studies are described as achieving results of “33 per cent or less,” while the superior results of MacCulloch et al. are described as “something of a mystery.”[115] An average response was estimated at around 40% overall, not much different from psychodynamic successes (39%).[116]

In 1975, a taped lecture by one of the field’s leading researchers was reviewed in the Medical Journal of Australia, and the reviewer was enthusiastic. He shows no sign of believing that the research community had rejected the evidence base of aversion therapy: “These lectures, theoretically, should be of use in introducing behaviour therapy concepts, clinical application, evaluation and limitations generally, especially to audiences remote from centres teaching and practising behaviour therapy.”[117]

A 1976 paper detailed success in treating a teacher who was a homosexual pedophile. He sought therapy because of attraction to the students he coached. After aversion therapy, his penile response to underage boys were unchanged, but he “had become much more interested in girls of his age, sexually aroused by them, and willing to pursue their company. He also reported almost no desire to involve himself with the boys he coached.” The authors concluded by noting that such self-reports were easily fabricated.[118]

Scientific publications like the above are a useful way of tracking what researchers believed to be true. Similarly, it is interesting to evaluate PhD dissertations and master’s theses published during these years. They show what trainees and their advisers and dissertation committees believed.

One dissertation from 1976 noted:

- Aversion therapy … has been frequently used to eliminate maladaptive approach behaviors.“ These behaviors include the various forms of sexual deviation, alcoholism, drug abuse, obesity, and smoking. In these cases the primary aim of therapy has been the development of aversive control over the undesirable habits.” [119]

- A non-electrical “technique has also been employed successfully in the termination of a variety of undesirable behaviors; alcoholism, smoking, sexual deviations, and obesity.”[120]

- “Electric shock has recently become the most popular form of aversive stimulus. [Multiple Authors] have used electrical aversion with alcoholic addi[c]tion … [and] in the treatment of Heroin addiction. Finally, Marks and Gelder and Evans have used shock in the treatment of sexual deviation. The results with this stimulus have been relatively successful, tending to be more effective with sexual deviations than drug addictions.”[121]

- “Similar procedures have been employed with transvestites, drug addicts, and obese clients. In general, these studies have been relatively effective, resulting in 40-60% success across a variety of deviant behaviors.”[122]

- “Feldman and MacCulloch have reported good results in the treatment of homosexuals reporting 64% success at 6 months follow up. However, MacCulloch, Feldman, Orford, and MacCulloch, using an identical procedure with alcoholics, reported zero success with four patients.”[123]

A second 1976 dissertation quoted Tanner’s defense of shock therapy approvingly.[124] A master’s thesis urged “that electric shock be considered the optimal aversive agent because precise control over the rate of onset. duration. intensity. and temporal proximity to the C[onditioned] S[timulus] was possible.”[125]

It seems clear that electric aversion therapy was not being abandoned—for homosexuality or many other conditions.

[112] G. Terence Wilson and Gerald C. Davison, “Behavior Therapy and Homosexuality: A Critical Perspective,” Behavior Therapy 5 (1974): 25, emphasis added.

[113] Lynn P. Rhem and Ronald H. Rozensky, “Multiple behavior therapy techniques with a homosexual client: a case study,” Journal of Behavioral, Therapeutic & Experimental Psychiatry 5 (1974): 54.

[114] Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behavior, 35–42, 52–143.

[115] Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behavior, 145, 147.

[v] Bancroft, Deviant Sexual Behavior, 148.

[116] Ronald W. Field, “Book Reviews: A Neo-Pavlovian View of Behaviour Therapy: Tape 2-Aversion Therapy of Homosexuality,” in Medical Journal of Australia (20 September 1975): 489.

[117] Stanley R. Conrad and John P. Wincze, “Orgasmic Reconditioning: A Controlled Study of Its Effects upon the Sexual Arousal and Behavior of Adult Male Homosexuals,” Behavior Therapy 7 (1976): 163, 166.

[118] Timothy John Greenough, “An Analogue Study of Specific Parameters of Overt and Covert Aversive Conditioning,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Western Ontario, February 1976.

[119] Greenough, 1.

[120] Greenough, 8.

[121] Greenough, 10

[122] Greenough, 11.

[123] HD Harrison, ” Aversive Control and Contingency Management: Two Environmental Treatment Procedures and Educational Progress in a Remedial Learning Center at a Minimum Security Penal Institution,” D.Ed. dissertation, Memphis State University, April 1976, 39.

[124] Kenneth F. Foti, “Behavioral Treatment of Alcoholism: an Evaluative Review,” Western Michigan University, master’s thesis, 1976, 21.

Philosophy and value judgments

By contrast, in the latter half of the 1970s, some behaviorists began to discourage aversion therapy.

We might think that this was because they regarded the evidence as having showed it had failed. Instead, some did not think it mattered whether the treatment worked or not.

In 1974, Gerald Davison—president of the American Psychological Association—said:

Behavior therapy is nothing if it does not represent a profound commitment to dispassionate inquiry. The best of the literature, and there is much of it, illustrates a sober appraisal of other approaches to behavior change as well as candid appraisals of what behaviorists themselves have accomplished.[126]