Ben Spackman explores how assumptions shape our reading of scripture, emphasizing the importance of understanding context and foundational beliefs about revelation, prophets, and scripture. He advocates for a balanced approach that combines scholarly tools with spiritual insights to enrich faith and scriptural understanding.

This talk was given at the 2022 FAIR Conference on August 5, 2022.

Ben Spackman, a PhD candidate in American Religious History and Mormon Studies Fellow, examines the intellectual roots of LDS creationism and evolution and brings expertise in Old Testament studies and religious history.

Transcript

Ben Spackman

Introduction

Thank you. There is so much I wanted to cram into this talk, and I did a fireside recently where one of the pieces of feedback said, “I like people who talk at light speed,” and so I decided I just really had to cut, cut, cut, cut. And so a lot of the things that I would use to illustrate or to buttress – Church quotes and things – there’s just not a lot of that in here.

My title is “First Things, Faith, and Reading Scripture Literally and Why It Matters”

Science and Religion

On June 12, 1950, Elder Joseph Fielding Smith sent Henry Eyring senior a letter. As a well-known scientist and serving on the general Sunday School Board, Eyring had been assigned to produce a manual on science and religion for the young men and women. Smith wanted to express Eyring his views on various scientific matters, which he derived from his readings of scripture and church tradition. These views were somewhat at odds with Eyring’s views and those of other Church leaders as well. What is relevant, though, is that Elder Smith concluded his letter to Eyring by asking, “Are not these conclusions reasonable?”

I am not aware of a response from Eyring, but I imagine he might have diplomatically replied with a statement he made elsewhere. Eyring might have said, “Your conclusions are reasonable given your premises; but I question your premises.”

Premises and Postulates

Now, Eyring talks about premises and postulates. We might also term these presuppositions or assumptions. These are fundamental beliefs, so basic, so ingrained, so taken for granted that we may not even be conscious of them. Everyone has assumptions; we often inherit them from the different cultures around us we are embedded in. They form our worldview; they give meaning to texts and events. They govern much of our behavior and shape our understanding of the world around us. More importantly, these assumptions are the unconscious point of departure for our understandings and interpretations of scripture, history, and events.

Joseph Smith taught a true principle that if we start right, it is very easy for us to go right all the time, but if we start wrong, it is hard to get right. President Uchtdorf clothed this principle in the modern example of a plane flight that unwittingly began with its heading off by two degrees, resulting in a terrible tragedy brought on by a minor error, a matter of only a few degrees. If we begin with assumptions that are wrong or perhaps only off by a few degrees, we may end up far astray.

Assumptions and Scripture

Now, I spend a good bit of time reading in technical and academic stuff, as well as in LDS archives, and I’m aware that most people don’t do PhD work in both Old Testament and American religious history. In that, I am outside of the norm. So, I tried to keep an eye on various message boards and places where missionaries and youth and Seminary teachers are talking about Church stuff. These are, in several cases, direct quotes or only minor paraphrases – things I have gathered from LDS missionaries, adult Seminary teachers, local Church leaders in various places, and others.

Joseph Smith’s translations of ancient scripture are 100% pure revelation. That’s why we can read them literally.”

“If it were anything other than history, God would have told us.”

“Joseph Smith’s translations are 100% reliable. What he has ‘translated’ is absolutely correct. Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, and when he declared something as scripture, I accept it as 100% because it came from the Lord.”

“Moses was literally told what to write down by God.”

I get very concerned when I see the manifestation of assumptions like this among Latter-Day Saints because they have more in common with Protestant fundamentalism than LDS scripture and teachings. They also happen to make for vulnerable testimonies. So let’s talk about assumptions, about four central things.

First Things

I call these four central things “first things,” analogous to the first principles of the Gospel. These first things are Revelation, which is communication from God to humans; Prophets, referring specifically to those prophets we sustain as Apostles within the church; Scripture, the canonized standard works; and lastly, Interpretation, I’ve set it off a little because it’s a bit of a different thing.

Now, my focus today is on assumptions around the interpretation of scripture. But as we all have assumptions, how we interpret scripture begins before we even look at the scriptural text. Interpretation begins with our assumptions about Revelation, Prophets, and Scripture. So, I want to briefly revisit some aspects of these three things.

Revelation: Adaptation

An aspect of Revelation called adaptation, that is, revelation often creatively adapts, updates, reinterprets, recontextualizes, or integrates elements of a prophet’s culture and environment, giving these elements new meaning and significance in the process. God rarely seems to create meaning ex nihilo.

An example of this is Jesus did not produce wine out of nothing, but from water. He transformed what was around him into what was needed. For those of us of a certain age, we may remember both the TV shows MacGyver and the A–Team, which tended to conclude with the main characters taking things in their environment and transforming them into something new, which led to the desired outcome of the particular episode. That is kind of what adaptation is.

Revelation: Accommodation

There’s also accommodation.

“Accommodation is God’s adoption . . . of the human audience’s finite and fallen perspective. Its underlying conceptual assumption is that in many cases, God does not correct our mistaken human viewpoints but merely assumes them in order to communicate with us.”

I spoke on this at my first FAIR conference, I think, and I noticed in the Liahona this very month, this from Richard Holzapfel,

God speaks in the cultural context of the life and time of a person or people. He communicates according to their understanding . . . the Lord kindly condescends” (which is historically an alternate term to accommodation) “to communicate His will in their language and culture so He can instruct and succor them.” This is accommodation.

Revelation: Responsive Specificity

Revelation is also responsive and specific; that is, it usually comes in response to a question or need due to a circumstance or situation. Therefore, revelation is often tied to the specific time, place, and setting of that situation, the bounds of that question or circumstance.

And here I think of Elder Holland’s talk about D&C 8 or 9 where Moses is at the Red Sea and says whoever needed more revelation than the revelation that came was certainly not expected, but it came in that circumstance.

Revelation: Partial, Progressive, and Revisionist

Revelation is partial, progressive, and revisionist. And here I’m thinking about Nephi’s principle of “line upon line,” Paul’s statement that prophets “speak in part and prophesy in part”, and that “many great and important things” are yet to be revealed, according to the Ninth Article of Faith. Now these great and important things, this future revelation, will likely cause us to rethink our understandings of the past, and not merely add to our knowledge. That’s what I mean by revisionist.

Prophets: Coparticipation

When it comes to prophets, coparticipation is an important understanding of the nature of prophethood. That is prophets are not divine typewriters, but participate in, and shape, the revelation that comes through them. If God imparts human aspects to revelation because of accommodation, human prophets also impart human aspects to that revelation.

This means that scripture is not solely divine but also bears strong human fingerprints. After the revelatory process, scripture passes through many hands – scribes, editors, translators, printers – and these people may or may not be inspired. All of this means that scripture is not a purely divine and perfectly coherent encyclopedia of timeless facts but a partial, progressive, multi-vocal, inspired record with strong human aspects to it.

As an aside and an example, when I read about the dispute between Apostles Talmage and Widtsoe and Roberts and Joseph Fielding Smith in the late 1920s and early 1930s, which is detailed in Saints Volume 3 Chapter 21, and how other apostles lined up, they were essentially approaching scripture and revelation with very different assumptions, and that led to very different outcomes that they could not quite reconcile.

Literal Interpretation

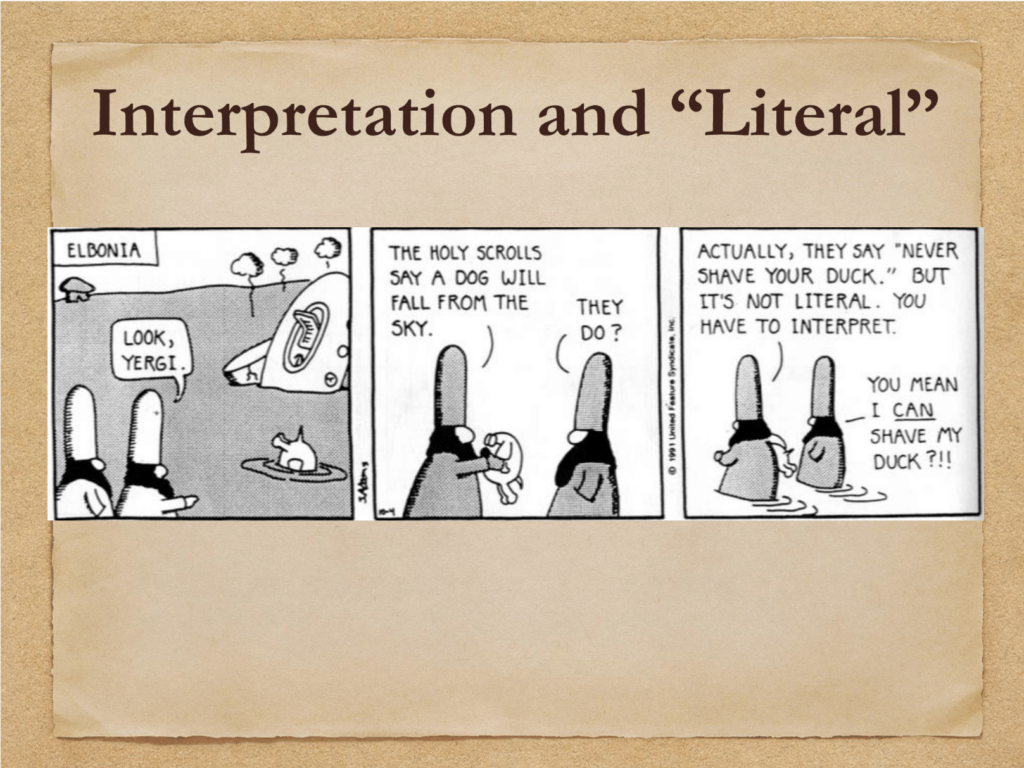

This brings me to my main topic, namely literal interpretation. I’ve used this Dilbert cartoon a good bit. It’s funny but also captures three common misconceptions about interpretation and what literal means.

Common Misconceptions

First is the misconception that literal means a surface reading, a face value reading, a reading where you are not interpreting. It embodies the second misconception that interpretation is something you only do when you don’t want to read literally, that is when you don’t want to accept the obvious face value, surface reading. Third is the misconception that interpretation produces nonsense and obscures more than it reveals.

It is also contingent, that is, one’s interpretation depends upon a number of things:

- It depends on our religious commitment–That is if I am an atheist I will interpret the Bible very differently than if I am a Catholic or a Muslim.

- It depends on our knowledge and skills. I read the Old Testament differently because of my training in Hebrew and Aramaic.

- It will depend heavily upon our assumptions.

- It will depend on our goals and methods. That is different methods of interpretation are like different kinds of tools. What you want to achieve will dictate what tool you want to use.

- And also it depends on our degree of inspiration.

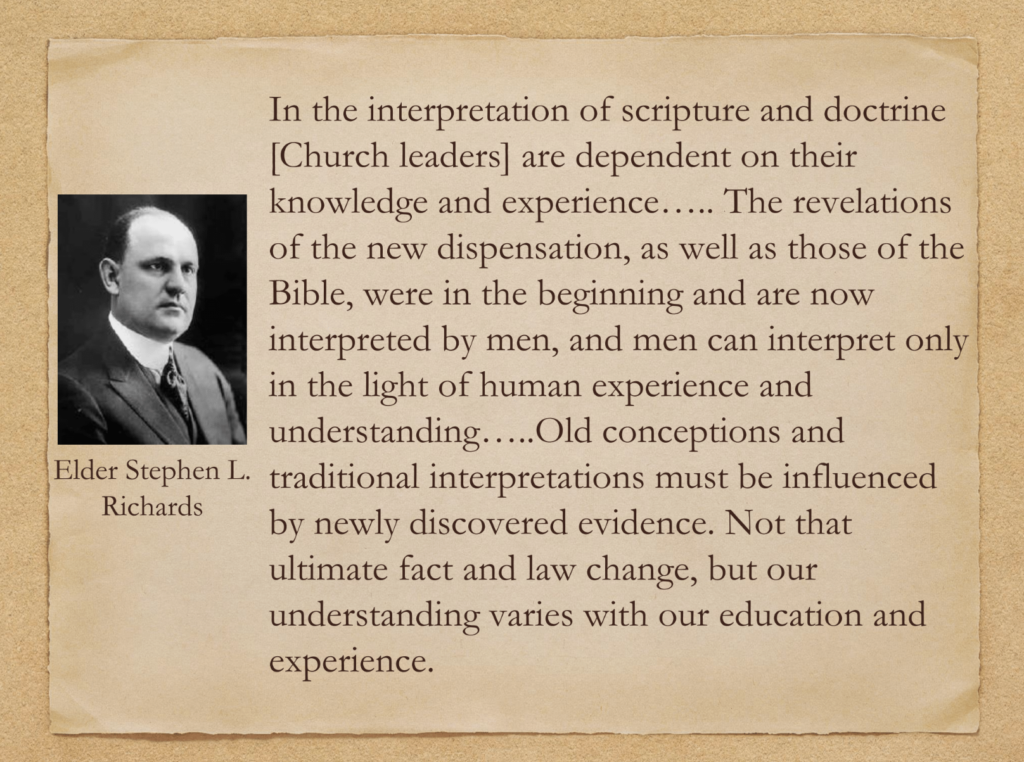

In general conference back in 1932, Elder Stephen L. Richards preached this:

In the interpretation of scripture and doctrine [Church leaders] are dependent on their knowledge and experience. . . . The revelations of the new dispensation, as well as those of the Bible, were in the beginning and are now interpreted by men, and men can interpret only in the light of human experience and understanding. . . . Old conceptions and traditional interpretations must be influenced by newly discovered evidence. Not that ultimate fact and law change, but our understanding varies with our education and experience.”

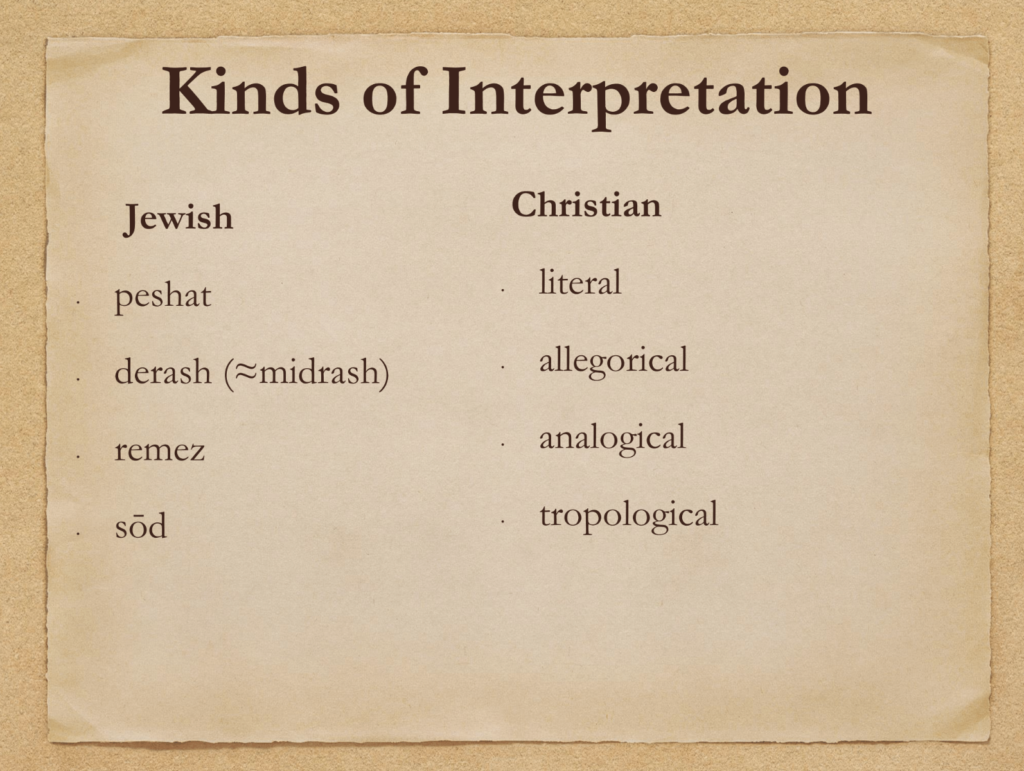

Having thrown all these terms at you, and noting that “literal” is one of them, we can make this very simple and just divide these into two categories. There is contextual interpretation, which is peshat and literal interpretation, and the other kinds all fall under the heading of non-contextual interpretation. That is, they’re kinds of interpretation that don’t depend on understanding any kind of context. In fact, they were kind of extra-contextual.

Meaning of “Literal”

Now, let’s focus on the word “literal.” This kind of literal Christian interpretation is actually quite old, and I want to drill down further into it. Is a literal reading, a face value or surface reading, as in the Dilbert cartoon? What does it mean? Can you simply open scripture and understand what Isaiah meant to his audience in translation with no context? What Genesis meant?

Intention

Peter Harrison, a historian of science and religion, says,

It’s important to understand that Augustine deploys the descriptor “literal” here in a way somewhat unfamiliar to modern readers, using it to distinguish his approach in this work from highly allegorical or moral readings of Genesis that were common during this period. Augustine sought, in his literal meaning, to establish the sense intended by the author.”

So for Augustine, literal means the sense intended by the author. In other words, if the author intended to write a parable and we read it as history, that would not be a literal reading. If the author intended poetry, a literal interpretation would recognize it as poetry. If the author intended history, a literal interpretation would need to recognize the genre as history. If the author did not intend to write a scientific text, then interpreting it as a scientific text is not a literal interpretation.

How well did Augustine’s usage of “literal” carry down through history? Among the reformers, the literal sense became the dominant approach. These others became less important, they focused on that. But it was not just the reformers.

Pope Pius XII stated,

Let interpreters bear in mind that their foremost and greatest endeavor should be to discern and define clearly that sense of the biblical words that is called literal . . . so that the mind of the author may be made abundantly clear.”

If a literal interpretation is trying to recover and represent what the author intended, the mind of the author, then a literal interpretation requires trying to get into the author’s context.

Let’s look at some others’ ideas. I’m not going to get into the background on all these people, but they’re historians, they’re Bible scholars, they’re Catholic, they’re Protestant.

Others’ Ideas

For Alistair McGrath, the literal sense is the sense intended by the author. For Tremper Longman, literal is the type of interpretation where one reads passages as organic wholes and tries to understand what each passage expresses against the background of the original human author and the original situation. For Father Joseph Fitzmaier it is the sense which the human author directly intended, in which the written words conveyed.

Even in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, it’s stated that “In order to discover the author’s sacred intention, the reader must take into account the conditions of their time and culture, the literary genres in use at that time, and the modes of feeling, speaking, and narrating then current. ‘For the fact is that truth is differently presented and expressed in the various types of historical writing, in prophetical and poetical texts, and in other forms of literary expression.’”

Literal Reading and Context

So, a literal reading requires context. It requires understanding the language, “the conditions of their time and culture, the literary genres in use at that time, and the modes of feeling, speaking, and narrating,” the genre, history, setting, and authorship of a book or passage. In other words, you cannot achieve a literal interpretation of scripture merely by opening it up and reading the words in English. It requires context.

Now here’s the problem: scripture comes to us already decontextualized. Even in politics we often hear accusations of taking things out of context, and that sounds like something we do actively. One of the problems with scripture is that since it comes to us decontextualized, we have to do work to put that context back in, which I’ll talk about in a minute. But we read scripture out of context by default. Why is that the case? Well, we’re going to get to another assumption around scripture.

We Are Not the Primary Audience

We are not the primary audience. Neither Genesis, nor D&C 132, nor Matthew was written for Latter-Day Saints in Utah in 2022. “The Bible was written for the people of its day. . . . Isaiah, Ezekiel, etc., had revelations for themselves, not us.” That’s John Taylor as paraphrased in the Instructor in 1945.

For the original audience could go without being said. Prophets were speaking to their contemporaries. They spoke the same language, lived in the same place, and understood the culture and references. We do not know those things anymore by default because we don’t share that cultural or other context with the authors of scripture. And that goes for the D&C as well. Scripture thus has numerous unstated implicit contexts that were known to the original audience but not to us.

Implicit Contexts

Let me give what I hope are some simple and understandable examples. If, in Elders Quorum, I were to offhandedly make the remark, “The Cowboys defeated the Giants,” sports fans might immediately understand that this is an NFL football game, that the two teams were from Dallas and New York, and that one team had won the game while the other had lost. Now I am one of the people in Elders Quorum who would be like, ‘I recognize this is a sports reference but I have no idea what sport it is.’

There is an assumption of implicit context here, and if you have that context you understand, and if you don’t, you might kind of go “uhhh. . . whatever.’

If we change this to “The Giants defeated the Rangers,” well, now you’re talking about baseball, and the two teams are San Francisco and Dallas, Texas.

Now, I want you to imagine that you are living 150 or 200 years ago when football and baseball have not been invented, and sports as a pastime barely exists. Even then, it’s mostly just for gangs and lower classes. If I had just told you one of those exact same sentences that the Cowboys defeated the Giants, how do you think you would understand my meaning? This is essentially how we approach scripture. There are implicit contexts that we don’t know about.

Scholars Say

Biblical scholar Conrad Hyers says,

We cannot simply abstract scripture from its original context of meaning, as if the people to whom it was most immediately addressed were of no consequence. And, having created a vacuum of meaning, we cannot then arbitrarily substitute our own issues and literary assumptions.”

Yet, this is what we do.

Sydney Sperry, an Old Testament scholar, points out,

We ofttimes read our Bible as though its peoples were English or American and interpret their sayings in terms of our own background and psychology. But the Bible is actually [a Near Eastern] book. It was written centuries ago by [Near Eastern] people, and primarily for [Near Eastern] people.

Widtsoe, Quoting Brigham Young,

To read the Bible fairly, it must be read as President Young suggested, ‘Do you read the scriptures, my brethren and sisters, as though you were writing them a thousand, two thousand, or five thousand years ago? Do you read them as though you stood in the place of the men who wrote them?’ This is our guide. The scriptures must be read intelligently.”

So if we want to interpret scripture literally, we need to try to read it with attention to its original setting, language, contest, and so on.

How Can We Find Context?

Now where do we get all this contextual information to read literally? We get it from scholars and experts. We get it from reference works, study Bibles. We get it from commentaries. We get it from personal study of ancient languages or older English, history, geography, per the commandments to us as members of the Church in the Doctrine and Covenants.

Well, okay, that all sounds really scholarly and elitist, and to some extent it is. Latter-Day Saints inherited from the 19th century an extremely populist approach to scripture. No one could tell us what scripture meant. All you had to do was open it and read it. And we have wrestled with the effects of that populism since then.

I do not believe that God intended scripture to be cryptic, hidden, or obscure. I do not believe God intended scripture to belong to scholars or people who mastered dead languages. Not at all. But since God spoke to the specific needs of those past times and places in a different language than he would speak to us today, we must learn that past language and setting to fully understand past scripture, including the D&C. That is the work of specialists of historians, linguists, Bible scholars and so on.

This is what the Church has done very much with the D&C. We have Saints, We have Revelations in Context, we have chapter headings, we have a number of aids to provide that context to us that we no longer know, even though we speak the same language and live in roughly the same place and are only separated by 200 years. Multiply that by ten, move it to the Middle East, and you’ve got the Bible.

Reading With the Spirit

Now, what about the role of the Spirit? I don’t talk about using the spirit a lot in relation to this topic for several reasons. First of all it is not my prerogative, nor my gift or calling to instruct people in sensitivity to the Spirit. Moreover, because we hear it so much from other sources, I take it as a given that people are praying before they open their scriptures, that they are trying to open their minds to inspiration from God.

More importantly, however, the Spirit is not something you can really use like a resource on your shelf. The Spirit is not a method that you control. You do not pull the Spirit off the shelf and look things up in it. It does not work that way. Moreover, the Spirit is not a shortcut or substitute for actual study. Perhaps, with rare exceptions it will not teach you things that are available to you already through other means.

Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon through the spirit and power of God, but to learn Hebrew he had to hire a teacher and get a grammar and lexicon to work through. Did the Spirit help? Yes! Did it do the work for him? Absolutely not!

Seek the Spirit

People who self-righteously refuse to read anything because they prefer the Spirit to man’s scholarship are declaring in essence that they are abandoning themselves to their confirmation bias and reading scripture unconsciously through their modern assumptions and traditions.

Did Joseph shun Hebrew because it was human scholarship and he preferred the Spirit? No. So is the Spirit important? Absolutely! Seek the Spirit in your studies regardless of what you are reading. I feel that this is a, “this you should have done and not leave the other undone” kind of situation. The Spirit and scholarship are not an either or, but a both and.

President Nelson talks about how good information leads to good inspiration. He consults experts when he wants to know what the Hebrew means, and with other things. Elder Ballard has talked repeatedly about needing experts, specifically in terms of ancient scripture and history. Elder Holland, in 2021 talked about how he was studying scripture that year using a particular study Bible.

So by all means, seek the Spirit and live the kind of committed disciple’s life which will not give God any obstacles to inspiring you. You shouldn’t need me to preach the spirit at you because you should already be seeking it, in other words.

BYU professor Gaye Strathearn in the Church News recently said,

a two-fold interpretation is necessary to increase spiritual and practical understanding of the scriptures and their doctrines. . . readers need to understand how it–as well as interpret the text in a way that is personal and applies to them currently as individuals and families.”

That is, we need to seek both the literal meaning of scripture through scholarly means, and the spiritual, non-contextual application or meaning to us individually, our families, and those groups we are responsible for due to our callings.”

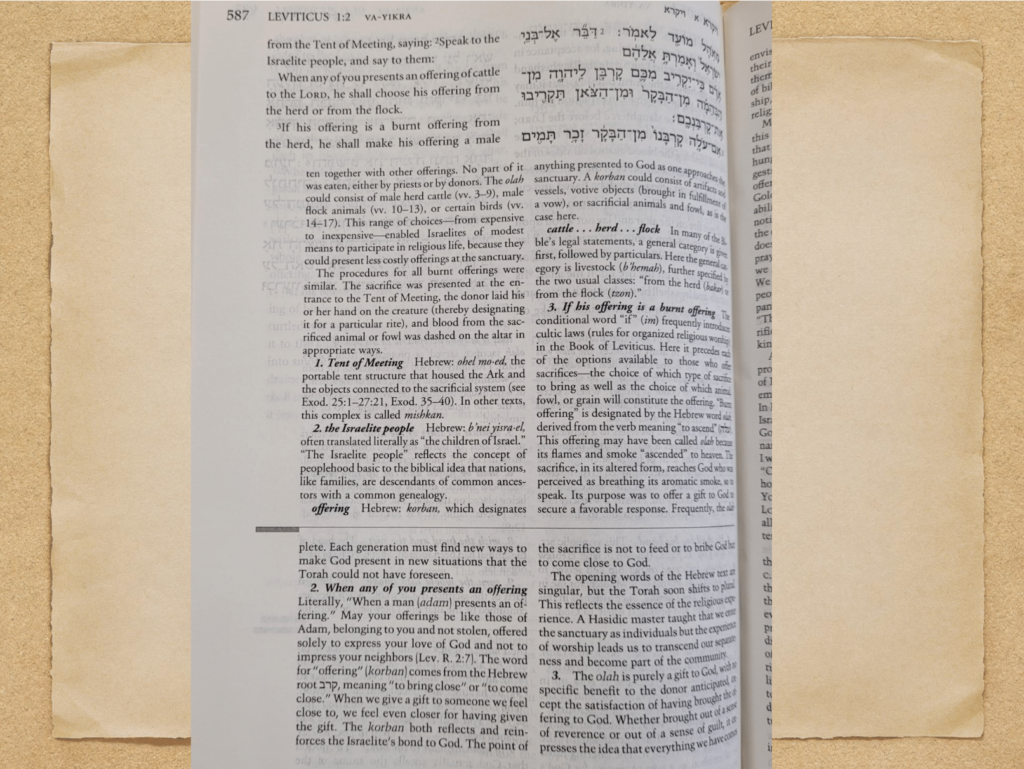

Now, both of these kinds of interpretations can exist. It is something I do; it is something my colleagues at the religion department do. But I want to show it very visually here that these two kinds of interpretations—scholarly, contextual, and non-contextual, spiritual other, visually—can coexist as long as we don’t confuse them with each other.

Examples

This is a Jewish Torah commentary called etz chaim, the Tree of Life. At the top, it has the scriptural text in Hebrew and a translation. Underneath, it has two tiers of commentary. The top tier is modern, scholarly, contextual Jewish commentary; it is the literal reading. The bottom tier is traditional, ancient Rabbinic commentary, which is authoritative for how to live your life. These two tiers coexist, even if they sometimes contradict each other.

Within the Christian tradition, you have things like the conservative Evangelical NIV Application Commentary. In its introduction, it explicitly says that the philosophy of the commentary will be to seek the literal, contextual meaning and then to try to bridge the gap into our own modern lives, which are very different from, say, pastoral nomads in 2000 BC. How do we make that relevant to us today? These two things can coexist.

Conclusion

Now, to summarize, the assumptions we make about revelation, prophets, scripture, and interpretation affect our faith. I had a couple ask me recently—he’s serving as the Stake Executive Secretary, and she’s the Relief Society president, so they are committed people, they are readers—and they said to me, “You know, we kind of asked each other the other day, ‘How is it that Ben stays active when he knows all this stuff?'”

And I said to them, “It’s not about the data; it’s not about the facts. It’s about the assumptions and the framework that you interpret those things through. My assumptions are different because of my training, where they got explicitly questioned and kind of hammered out and reformed, and I was reading about other people’s assumptions. But, things that do not bother me have, at times, led other people directly out of the Church, both in history and currently. I am in contact with some of them.”

Seek Good Information

A literal reading of scripture is a deeply contextual reading, not a face-value or surface reading. Some Latter-day Saints will say things like, “Well, I think I can understand the plain language of scripture.” And my response is, “Plain to whom?” It’s only plain to you because you’re not reading anything else, because you assume that words don’t change meaning over time, that all the necessary context is here in the language. And that’s not true.

We need to seek both literal interpretations and inspired personal, non-contextual interpretations simultaneously for a religious faith. Elder Maxwell and Elder Eyring have talked about becoming disciple-scholars, and I am very much of the belief that people need to seek good information as much as possible. I do not think we all need to get master’s degrees in religion. I don’t think that Seminary or Institute should be technical scholarly discussions. But especially those of us who teach and lead need the best information possible; we need the best assumptions available to us.

Discipleship can survive without scholarship, although scholarship can help. On the flip side, scholarship without discipleship is just cold and dead—there’s no point. I take no joy in arguing about textual criticism or Hebrew vowels. All of this stuff serves a greater purpose for me. It is the marriage of that—as a disciple-scholar—that has real meaning, depth, and power to retain testimony.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you, Ben. So, as I mentioned before, we not only have our audience here, but we have our audience watching online. And so, this first question comes from Russia. It says, “How can we preach this more balanced and nuanced approach in a more conservative, old-school place? In this part of the world, more progressive members tend not to even consider these issues around literal interpretations.”

Ben Spackman:

Right. Well, I hate to reduce this to a technique—it sounds so adversarial—but one of the things that I tend to do, that I have seen is effective, is if you can find General Authority quotations that advocate certain positions or ideas, people tend to at least give them the benefit of the doubt. They think, “Well, okay, it’s not you saying it—it’s Stephen L. Richards. It’s Elder Maxwell. It’s so-and-so.” And those also help to show that our tradition is not monolithic in many regards.

If I can detour slightly—and it relates to literal interpretation—Joseph Fielding Smith was very big on literal interpretation. He thought literal interpretation meant we all had to be young-Earth creationists and reject evolution. And one of the ways that I deal with that, with Latter-day Saints who are struggling with it, is I point out all of the other apostles who read scripture through different lenses and who said, “I believe scripture too, but I think there is room in scripture for evolution to be real.”

I also try to help people see that the assumptions they have inherited… I mean, I don’t know that anyone in here might have been able to say, “What is a literal interpretation?” before coming in—it would have just been tradition, as opposed to the good information. You can say, “Well, look, literal doesn’t mean what you think it does.” We all think that literal interpretations have power, that somehow they’re more authoritative because they’re obvious to us.

And it’s true that the literal interpretation, when properly understood, has a kind of authority that others don’t. If President Nelson preaches a sermon, what he intended to say in that sermon is more authoritative to the Church than my personal understanding of it, even if we can’t quite get at both of those things equally.

So, I try to help people understand their assumptions. I try to point out statements from other Church leaders that broaden the tradition, and that tends to be very helpful to people.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. I think of just the term “defensible space.” That is a short term, but I’m from Redding, California where we’ve had fires recently. And so, those words, even though they might mean the same thing to other people, the intensity of your feeling regarding those words is very different. You know, when you’ve had people who’ve lost homes because they haven’t done that versus someone who’s just like, “Oh yeah, we should do something about that.” So you not only have the words, but you have the intensity of the words that make a difference sometimes.

So, how can we recognize when scripture, revelation, and inspiration are divine and not human? There’s a good one for you—good luck.

Ben Spackman:

I will just go back to J. Reuben Clark in the First Presidency in 1954. He said, “The only way to tell when something is inspired is to be inspired yourself.” And I should point out that he gave that in 1954. Joseph Fielding Smith’s young-Earth creationist book, Man: His Origin and Destiny, had just been published, and it was being pushed very hard on BYU professors and CES. President McKay was very unhappy with this, and when he heard what was happening, he sent President Clark to give that speech in response. So, for people who asked, “Is this book or this position inspired?” He said, “You’ve got to know that for yourself, but it doesn’t represent the Church position.”

Scott Gordon:

I have three or four questions here that are essentially the same thing. Hopefully, I can say this in a way that encompasses all of them. Some of the Book of Mormon writers say that it is written to us. How should our literal reading of the Book of Mormon be different from other scriptures in light of this?

Ben Spackman:

Yeah, so, I mean, obviously, we can’t get at the same kind of context with the Book of Mormon that we can with the Bible, and it’s also kind of its own unique case. But we’ve also misread it in certain ways. President Benson very much repopularized the Book of Mormon and the idea that it was for our day, as either Mormon or Moroni says.

But in the small plates, Nephi makes clear that he is writing for his brethren—for his current people. And we see the effect of that in Mosiah and Alma, where the small plates are key in convincing the Lamanites that the traditions of their fathers were wrong. So, at least when Nephi is saying who he’s writing it for, he’s not writing with us in mind—he doesn’t have that vision. He’s writing for his near contemporaries.

Now, when it comes to the statement that the Book of Mormon was for our day, when he says, “I have seen your day,” I don’t know what that means. Does it mean that he saw Joseph Smith’s day? Does it mean he saw the general future? Was it kind of like the vision of Moses, where there was not a particle that he did not perceive—that he got this, you know, everything all at once?

And then I would further point out—and perhaps I’m nitpicking here—but it wasn’t written for our day; it was edited for our day. The sources that he’s drawing from and putting together certainly weren’t written for us. It’s the editorial overlay and shaping that is for us—again, whatever “us” is in his vision where he says, “I have seen your day.”

Scott Gordon:

Here’s a tough one. I know many people who feel they can’t contribute to discussions on scripture in church because they struggle academically or don’t have a high level of education. How do you suggest helping these people understand that their voices also have value, and that we have much to learn from them?

Ben Spackman:

Oh, that’s a fantastic question because it’s one I don’t know how to respond to well. There is a long history in the Church of leaders being very conscious about not making intellectual tiers in the Church.

There have been several times where—let me give a story. In the 1960s, there was a guy writing manuals for the Church while he was a grad student. The general authority over these manuals came to him and said, “We need a major shift. You need to write all manuals so they can be used by a convert of three weeks.” And they said, “You want all the manuals to be accessible and teachable to someone who’s been a member of the Church for three weeks?” And he said, “Yes.” They asked, “What if we write two tiers of manuals—one that’s kind of basic and one for other people?” And he said, “Nope, we can’t do that. That’ll create divisions in the Church, and we won’t do it.” And this manual writer said, “So that’s what we did—that’s how we wrote our manuals.” That has kind of carried down.

Now, I think one of the things we can do that we don’t do well somehow is encourage everyone to read closely, because there are a lot of insights that just come from reading scripture slowly and carefully—no degree required. The other thing we can do that is also extremely accessible, at least when it comes to the Bible, is encourage people to get another Bible translation, because that very much lowers the barrier to understanding.

And those—you know, you can pay five bucks for an NRSV paperback. You can get the free NET Bible online. Those are low-cost, easy, understandable—they lower the barriers. So, modern Bible translation and just modeling what it means to read closely and carefully, to pay attention to words—it’s not something we do well. We’re great at taking things out of context.

Scott Gordon:

Just so they’re clear, what Bible translations might you recommend again?

Ben Spackman:

Well, I have a page on my website where I go into this in depth, but for free, you can get the NET Bible online—the New English Translation. The advantage to that is it can have 50,000 footnotes—it’s hard to put that into paper otherwise. My default recommendation is the NRSV—the New Revised Standard Version—that comes in a variety of editions. I like the one called the NRSV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible. It has lots of notes on the cultural background.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, so let me give this to you as your last question, and we have a few people in the audience who want to hear this one. When do you think you can have an article on this topic in the Church magazines?

Ben Spackman:

That is not dependent upon me. But, let’s see. This recent article by Holzapfel that I quoted—August 22, online only—covers some of this territory very gently. I suspect he has been reading some of my material, actually. But, that’s just not within my power.

Scott Gordon:

I appreciate that. Thank you so much for what you’ve given to us, and I really appreciate it.

Ben Spackman:

Thank you.

coming soon…

Is literal reading of scripture necessary for faith?

Ben explains that literal reading, when understood as contextual, deepens faith and prevents misinterpretation.

Can scholarship coexist with spirituality?

He emphasizes the harmony between scholarly study and spiritual guidance, citing Church leaders who advocate for informed discipleship.

The role of assumptions in shaping faith and interpretation.

The importance of combining scholarly tools with spiritual practices.

Encouraging nuanced approaches to scripture to strengthen testimonies.

Share this article