Presentation by Matt McBride

Transcript

Scott Gordon introducing Matt McBride:

Our next speaker is Matt McBride. Matt is a longtime friend of FAIR—let’s put it that way—and has spoken before at our conferences. Without much further ado, I’m going to give as much time as I can, so I’m going to turn the time over to Matt.

Life Can Only Be Understood Backward

Thank you. It’s good to be here. I know some people advise starting talks with a joke, but as I glance at my notes here, I see that the first two words are ‘Søren Kierkegaard,’ so I’m not sure how funny this is going to be.

Nevertheless, Søren Kierkegaard once observed that while life must be lived forward, it can only really be understood backward. Occasionally, we become conscious of this in our day-to-day experiences. For example, we might find meaning in a severe trial months or years after it happened—meaning we failed to see in the moment of crisis. Meaning grows from memory. The act of looking back can be a sacred endeavor: ‘Turn your hearts to your fathers,’ ‘Search the scriptures,’ ‘Remember how merciful the Lord has been unto the children of men from the creation of Adam, even down to our time.’ As Latter-day Saints, we are urged repeatedly to gaze back beyond the confines of our own lives and stand on the shoulders of others, giants or not.

The corollary to all this is that someone needed to keep a record in the first place, to preserve it and work to make its insights accessible. Records of the past enlarge our memory—they make sacred remembering possible. Restoration scripture is replete with commands to record things: Adam’s descendants kept a book of remembrance, Nephi kept records for a wise purpose, and the Lord commanded the Saints at the first meeting of the Church in this dispensation to keep a record. Joseph Smith and his scribes and associates kept a magnificent record, indeed.

Time to Take Stock

As the Joseph Smith Papers team, my colleagues and I stand near the end of a 23-year period of sustained remembering—of scrutinizing the record that Joseph kept. We’ve endeavored to create a complete and open publication of his ‘large plates’ record, to borrow a phrase from the Book of Mormon. As we look back on this effort, it’s natural to try to take stock—to assess, even to quantify.

So, here’s one attempt:

- 22+ years

- 1,300-some odd journal entries

- 643 letters

- 155 revelations

- 27 print volumes

- 18,820 printed pages

- Almost 7.5 million words

- Nearly 50,000 footnotes (and as some of our team members like to point out, toe notes as well, which I think we might have invented).

It’s exhausting to create, and some might argue that it’s exhausting to consume and read. The question our team is often asked is: Can you distill this all down? Where is the meaning in all these thousands of documents? Who is the Joseph that emerges from an up-close examination of his corpus? In short, people want to know: What have we learned from the papers?

What Have We Learned?

If you were to ask each of my colleagues this question, they would probably answer it in completely different ways than I would. Each of them has their own approach because this historical publication, unlike most others, is not the work of a solitary scholar or the product of a few collaborators—hundreds of people have now contributed to it, each bringing their own perspective based on the small slice they worked on. So, today, I’ll make my own modest attempt to answer these questions and share a few thoughts about what I’ve learned from the papers.

We’ve certainly learned many new facts about Joseph Smith’s life. New documents have given us new vistas on early Latter-day Saint history, and I’ll mention a few of those during my remarks. At the same time, much of the value of the papers comes not in the form of startling new discoveries, but in how they confirm what we already understood in part, or allow us to speak with greater confidence, clarity, and authority than we could before about the Prophet’s life. I would argue that this is one of the most important legacies of the papers.

Coming Into Focus

Now, let’s see if I can advance my slide here… there we go. How many of you recognize the subject of this photograph? Hopefully, everyone.

Examining and contextualizing Joseph Smith’s papers closely over the years has done something like this for us. Now, I don’t want to exaggerate or claim that we now know everything there is to know about Joseph Smith or that we have a perfect picture of his life—far from it. But, as with this photo, we can now see the beloved subject of our study so much more clearly, as if we’ve put on corrective lenses after so many years of squinting. The papers clarify the surrounding landscape; they help us take in the nuances, and they show us how the smallest details contribute to the whole.

One example that stands out in my mind is the last volume of the Documents series, which was released just last summer. It chronicles the final six weeks of Joseph Smith’s life. It’s not the individual documents in this volume that stand out so much as the way the incessant stream of setbacks, threats, lawsuits, and frankly, missteps, causes the pressure on Joseph to build and build. You almost have to read through it blow-by-blow, or document-by-document, and let the effect of it all wash over you, getting inside of Joseph’s headspace during those tumultuous months by means of an extremely detailed documentary record, sometimes with 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, or 12 documents produced every day.

This detail makes the Nauvoo Municipal Court’s use of the city charter’s expansive habeas corpus provision to shield Joseph Smith from arrest look less like a power grab and more like an act of desperation. Again, we knew the pressure was on Joseph, but the dozens of letters, pleas, mayoral orders, military orders, warrants, and affidavits open wide a window on Joseph’s interior world in the final weeks leading up to his murder.

Never-before-published Sources

Much of what we have learned comes from never-before-published sources, and I want to highlight a few of those for you. With the gracious support and encouragement of the First Presidency, we published a number of previously unavailable records.

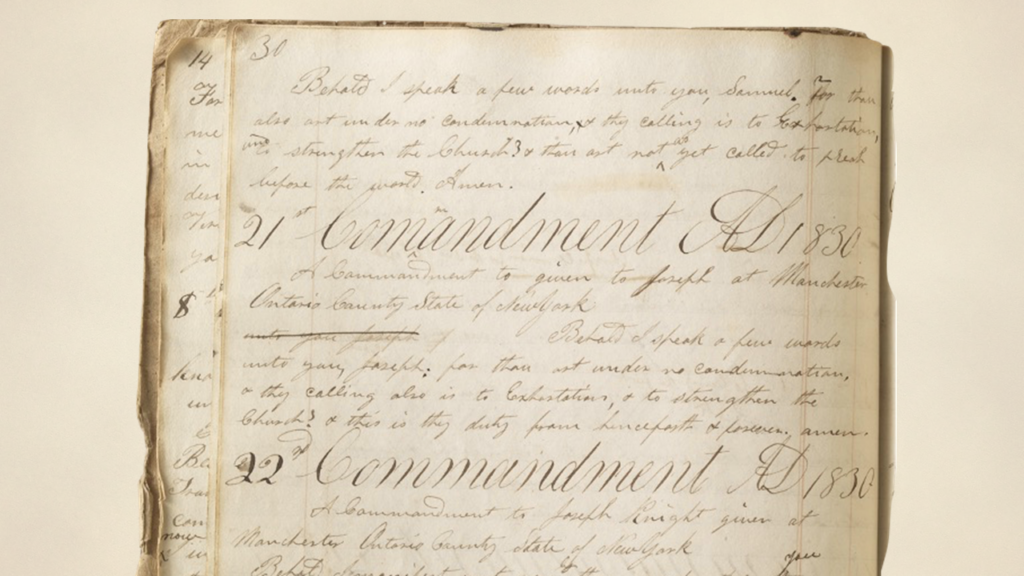

The Book of Commandments and Revelations

Notable among these is a record called The Book of Commandments and Revelations. This precious record served as the manuscript source for the publication of Joseph Smith’s revelations in the Book of Commandments and in the Doctrine and Covenants. It contains the earliest extant texts of many of Joseph’s revelations, and in some cases, it contains the only surviving manuscript copy that we have.

It also contains unpublished revelations, some of which were basically unknown. There’s a revelation commanding Joseph Smith to seek copyright for the Book of Mormon in Canada. There’s a sample of pure language, which was known previously only in part through a mention by Orson Pratt. I’ll talk more a little bit later about what this manuscript revelation book and other early records teach us about Joseph Smith’s revelations. But I want to highlight another new record that came to light through the Joseph Smith Papers, and that’s the Council of Fifty Minutes.

Council of Fifty Minutes

For so many years, there was mystique surrounding these minutes—what did they contain? Why had they not been published? Many supposed that the minutes harbored some explosive or embarrassing information about Joseph Smith or Brigham Young. Not so. The minutes do reveal the intense frustration and even anger experienced by Latter-day Saint leaders in Nauvoo toward state and federal governments. They detail both Joseph’s efforts to work within existing legal and political frameworks to improve the Saints’ situation, as well as his willingness to imagine a new theocratic constitution and explore places outside the sway of the U.S. government to carry out the commandment to build Zion.

Oh, it looks like I don’t have the most updated version of my slides. I had this really cool Lord of the Rings meme I added earlier, and I feel bad you’re missing out. For those of you who have seen The Lord of the Rings, imagine Elrond telling Isildur to throw the ring into the fire and destroy it. Mental picture.

Revelation and Scripture

William Clayton, who was the person who kept the minutes of the Council of Fifty, was directed to destroy those minutes, perhaps because they would appear treasonous. But he chose instead to bury them, and later he retrieved them and brought them to Utah. This is one of those instances in which, as historians, we’re grateful that Clayton chose to disregard the counsel of his leaders.

In the Council’s meetings, Joseph Smith shared teachings that ought to become classics, such as these statements on the workings of councils: He said, “The reason why men always failed to establish important measures was because in their organization they never could agree to disagree long enough to select the pure gold from the dross by the process of investigation.” On another occasion, he declared that he wanted all the brethren to speak their minds, to say what was in their hearts, whether good or bad. He didn’t want to be forever surrounded by a set of “doughheads.” If they didn’t rise up, shake themselves, and engage in discussing these important matters, he would consider them nothing better than deadheads. This may sound harsh, but it’s designed to provoke them—and us—to engage in the process of counseling together.

So, what have the papers taught us about revelation and scripture? In many respects, the volumes of the Revelations and Translations series of the Joseph Smith Papers are the crown jewels of the project. Together with the detailed historical context provided for each of Joseph’s revelations in the volumes of the Documents series, they provide a critical baseline for understanding the Restoration canon through Joseph Smith’s papers and the careful reconstructive work done by the project’s historians.

For example, we learn more about the context in which the revelations were given. We learn the questions that William McLellin asked the Lord, which were answered in Section 66 of the Doctrine and Covenants. We learn that Sidney Rigdon and Leman Copley eagerly left to share the revelation to the Shakers on the very day it was given. We also learn that other Christian reformers had established a Temperance Society in Kirtland, Ohio, at the time the Word of Wisdom was given. We gain insight into the financial challenges the Saints faced in the mid-1830s as they tried to fund the construction of cities and temples through a banking institution and other efforts. All of this serves as a backdrop for the revelations on tithing given in Far West in 1838.

We also learn in greater detail how Joseph’s translation of the Bible prompted new understandings of priesthood and church ecclesiastical structure. These are just a few examples, but what’s the big takeaway? What do these contextual clues tell us about the Latter-day Saint concept of revelation? Well, we see its dialogic nature. Revelation often comes in response to questions—so many questions. Joseph’s queries arose from his circumstances, his culture, his study of scripture, and his own spiritual yearnings. The revelations given in response did not come in a vacuum. Most of them weren’t divorced from the churn and turbulence of life in the world; rather, they were designed both to help the Saints navigate the ever-changing culture in which they lived and to cheer them along the way with glimpses of a glorious rest.

The papers also open a window on the “here a little, there a little” nature of revelation as experienced by the Prophet. Examples include Section 20 of the Doctrine and Covenants, known as the Church’s constitution. In our scriptures today, it appears as a flat text, giving the impression that it was received and dictated whole. But using the Joseph Smith Papers, we can trace its textual history to see that it was not only painstakingly edited for publication but also substantively amended by further revelation.

We believe that the earliest extant text of Section 20 was a surreptitious copy made and then published in the Painesville Telegraph. This copy lacks the texts of the baptismal and sacrament prayers, which most of us refer to in Section 20 frequently, asking, “Where are the sacrament prayers?” It’s not there. Instead, it simply refers to relevant passages in the Book of Mormon. By the time the revelation was copied into the Book of Commandments and Revelations months later, Joseph had not only added relevant excerpts from the Book of Mormon but also clarified other details, such as how frequently the Church’s elders were to meet in conference.

Joseph’s contemporaries seemed to understand that the revelation was still in a state of becoming. In one early copy, they labeled it “thus far the Church Articles and Covenants.” We could walk through similar analyses of Sections 27, 107, and others—these revelations came in pieces. We’re reminded of the verse in 2 Nephi about how the Lord giveth more to those who hearken to His earlier counsel, dispensing revelation line upon line according to the understanding of its recipients.

2013 Edition of the Standard Works

Many of the insights about scripture that arose from the project team’s research were incorporated into the 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. These changes include expansions and refinements to the introduction of the book, a few spelling changes in the text itself, and revised headings for 57 sections that correct dates, locations, and improve context relating to the circumstances in which the revelations were given. This, at least as I see it, is one of the most visible and lasting legacies of the papers.

How Joseph’s Experiences Shaped Him

At least as I see it, what have we learned about the way Joseph Smith’s experiences shaped him? There is a lot you could say on this topic, and I have time to give basically one example. The papers reveal the depth to which Joseph’s views later in life were shaped by the crucible of persecution. He and his family, along with his faith community, suffered acutely as a religious and cultural minority in a political and social climate that was frequently hostile to the Saints. This experience deeply attuned Joseph to the need to protect the rights of marginalized people, especially their right to worship how, where, and what they may.

Joseph developed an almost fierce distaste for how people in power trampled on religious freedom. His teachings on this topic from the Council of Fifty minutes help us understand what Joseph hoped a new constitution or a more just government would look like.

Every Man Acts For Himself

He said, “God cannot save or damn a man only on the principle that every man acts, chooses, and worships for himself.” Hence, the importance of “thrusting from us every spirit of bigotry and intolerance toward a man’s religious sentiments.” Joseph appealed to every man in the council, beginning with the youngest, that when he arrived at the years of maturity, he would be able to say that the principles of intolerance and bigotry never had a place in the Kingdom nor in Joseph’s own heart. Joseph said that after using every means in his power to exalt a man’s mind and teach him righteous principles, even if that man still inclined toward darkness, Joseph would continue to manifest the same principles of liberty and charity as though the man had embraced them.

A man, Joseph taught, should be judged by the law independently of his religious prejudice. Religious freedom had to be for everyone, not just for people who believed the way Joseph did. This was more than rhetoric for the Prophet. We know that he put his money where his mouth was. For example, when he learned that a Catholic priest from Iowa wanted to administer last rites to a dying parishioner but lacked the means to cross the river and make the trip, Joseph paid his passage on a ferry and loaned him a horse.

Joseph’s Character

What have we learned about Joseph’s character from his papers? Well, here we learn—but mostly relearn—things we already knew. We relearn that Joseph was quick to forgive, that he was generous with his time and means, and that he was prone to see the best in people, which often meant that he felt the sting of betrayal. He cared deeply for the plight of the poor, and he turned to God in almost every aspect of his life. Again, the cumulative effect of the thousands of small details in the papers is the project’s most important contribution to our understanding of Joseph’s character.

One accusation that has dogged Joseph, going back almost to his boyhood, was that he was a deceiver or a charlatan. It’s extremely difficult to maintain this assessment in the face of thousands of documents—public and private—that portray an earnest belief in the revelations he received. He shaped his life around them, risked financial ruin to carry them out, and died defending them.

An Ardent Joseph Smith

One of my colleagues put it this way: “What emerges from the papers is a Joseph Smith who ardently believes his own revelations.” It is a Joseph Smith who is less jocular and unserious than we might have supposed. His serious business was to live and die by every word that came from the mouth of God. The idea of Joseph Smith as a conscious deceiver falls apart under the collective weight of the papers.

At the same time, the papers show us more clearly than ever just how human Joseph was. He was somewhat hapless as a businessman—I’m trying to be generous here. His ideas about race and gender roles were deeply informed by his surrounding culture. He had a temper, and he sometimes engaged in violent altercations with people he believed had wronged him. It’s easy to get the impression from a few of Joseph’s sermons that he had an overinflated sense of self and that he was given to bravado. Indeed, he had his moments. He once said, “I have more to boast of than ever any man had. I’m the only man that’s been able to keep a whole church together since the days of Adam. The followers of Jesus ran away from Him, but the Latter-day Saints never ran away from me yet.”

But we can read these rhetorical flourishes in a different light, or as carrying a different tone, when we place them in context—first of all, in the sometimes hyperbolic preaching culture of the day, but also in the context of Joseph’s own willingness to publish revelations in which God chastised him for his failings. Even more so, when we consider statements by new converts and non-Latter-day Saints who found Joseph’s lack of pretension striking enough to comment on frequently. For example, one person said, “He does not pretend to be a man without failings and follies; neither is he puffed up with his greatness, as many suppose, but on the contrary, he is familiar with any decent man.” Another said, “I found Joseph familiar in conversation, easy, and unassuming.” His non-Latter-day Saint attorney noted, “He was very courteous in discussion and would not oppose you abruptly, but had due deference to your feelings.”

One instance in which Joseph’s self-awareness shines through is the only time he was unambiguously convicted of a criminal offense. This happened in 1843. Joseph had visited a city lot in Nauvoo that he believed had been unfairly seized by a county tax collector. The discussion between Joseph and the tax official escalated from a verbal argument to a physical confrontation, and Joseph got the better of his rival. Immediately afterward, Joseph voluntarily submitted to a local justice of the peace, confessed his guilt, and insisted on paying a fine for his actions.

Well, there’s a lot more that we could say.

Keeping A History

Dr. Laurie Maffly-Kipp noted at a recent conference that one of the significant contributions of the Joseph Smith Papers has little to do with Joseph himself but rather the way it illuminates the lives of those around him. While the papers project centers on the lifespan of Joseph Smith, the portrait it paints is of an entire community at work. It brings to life the everyday labors of many of the early Saints, naming many whose names would otherwise not make it into synthetic histories. Indeed, we have made an effort to highlight the contributions of the thousands of men and women whose faith in the revelations profoundly shaped the history of the Church but who are little known.

“I think of the efforts of one of our team members, Elizabeth Kean, to understand the material culture and day-to-day life of those who lived in frontier communities, using details found in Joseph Smith’s financial records. Or the work that Brent Rogers has done to flesh out the biography of Vienna Jaques. The papers have theological and devotional implications as well. In them, we learn more about the development of Church organization, about priesthood, about the Saints’ efforts to build a Zion community, and about the origins of our temple doctrine.

But I want to close by reflecting on what we’ve learned about our efforts as a Church—specifically as a Church History Department—to keep and share a record of Church history. The project has taught us that our history can withstand the most intense scrutiny. By deciding to be fully transparent about Joseph Smith’s life, we hoped, in Richard Bushman’s words, that there would be no rocks we would turn over and find a scorpion. The Church essentially said, ‘We’re going to turn over all the rocks,’ and as Richard quipped, ‘It proved a marvelous gamble.’

We have learned, or relearned, that a habit of historical transparency strengthens trust in the Church. We have learned, or relearned, that faithful people can produce rigorous scholarship and have their faith strengthened in the process. We have also learned, or relearned, that aspects of Church history are challenging for many Latter-day Saints to reconcile and that we need to give our best efforts to minister to them, particularly those with sincere questions about Church history.

In addition to learning from new sources—oh, excuse me, yes—yeah, I’m sorry. In addition to learning from new sources, we also learn from the papers’ consistent application of rigorous standards of analysis. This has spiritual consequences. In today’s world, one of the challenges of the digital age is a sustained assault on truth. As the internet has democratized publishing, it has become more difficult than ever to sift through the many voices and arrive at reliable conclusions about even simple matters. Latter-day Saints are vulnerable to distortion and exaggeration about aspects of our history, even from well-meaning people, and this puts at risk our ability to engage in the kind of sacred remembering that we’ve been encouraged to do.

The Joseph Smith Papers tries to model what a reliable source of historical information looks like. It considers all the sources, assesses their creative motives carefully, weighs them against each other, places them in context, and is measured in its conclusions. This approach to history is not the least important thing we can learn from the papers.

A ‘Lunar Mission’

Former Church historian Steven E. Snow was fond of calling the Joseph Smith Papers the Church History Department’s ‘lunar mission.’ Just as NASA’s lunar program yielded technological advancements far beyond the original intent and scope of the program, the Joseph Smith Papers project has done more than just illuminate the life of the founding Prophet; it has helped change the way we do history.

Most Saints won’t read the volumes of the Joseph Smith Papers, but we work hard to make insights from the papers as widely accessible as we can. We’re currently working on a revised and updated compilation of Joseph Smith’s teachings. It will distill many of the most important sources from the papers, present them in an easy-to-read edition, and ensure that they’re widely translated. And, as President Oaks announced at our Joseph Smith Papers conference last summer, the First Presidency has commissioned a new biography of Joseph Smith to be authored by Richard Turley Jr. Our Joseph Smith Papers team is excited to be involved in supporting that effort and thus to continue building on the foundation of the papers.

Other Projects

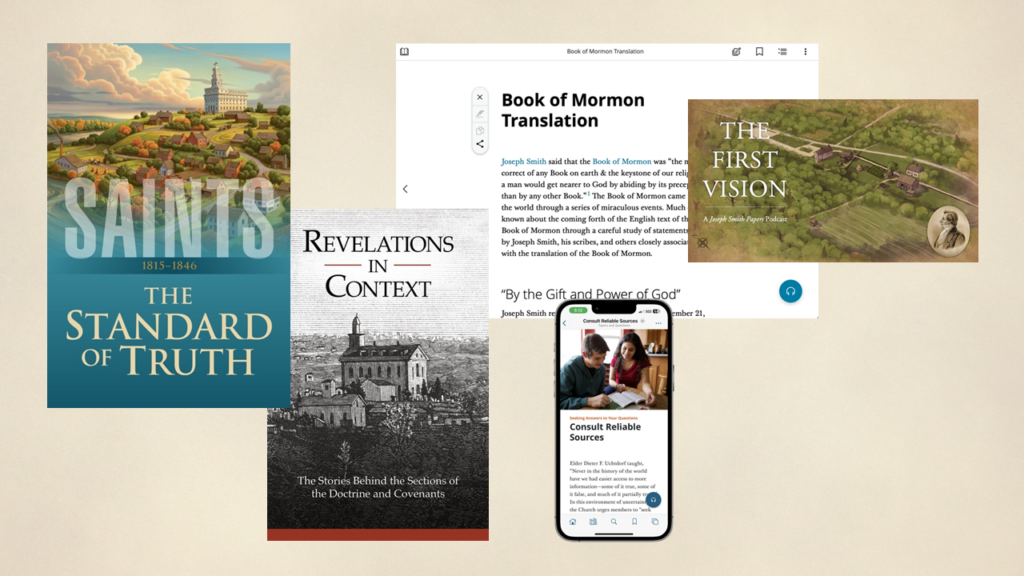

As you can see here, there are other examples of the kinds of projects that we have produced that build on the work done by the Joseph Smith Papers team.

Millions Shall Know Brother Joseph Again

In the end, we hope that our efforts will not only help millions to ‘know Brother Joseph again’—in the sense that we may be able to reach more people than ever through products such as these—but also because we now have the resources to know him more completely.

Scott Gordon:

“He said he’d be happy to take some questions. So, uh, I can… we can either take them from the floor, or I could… Should we just take them from the floor? Anybody have any questions?”

Audience Member:

“Yes. So, make sure you repeat the question they ask.”

Scott Gordon:

“So, the question is: How was the papers project funded, and why? And why was it funded that way?”

Matt McBride:

“Ah, it’s a straightforward question with a somewhat complicated answer, but I’ll try to keep it fairly simple. The Larry H. Miller family were a key funder of the Joseph Smith Papers. But it’s not true to say that the Church didn’t fund the papers—it was funded jointly by the Church and by the Miller family, and has been for quite some time, since the papers moved from BYU up to the Church History Department, about more than a decade and a half ago.

Part of the reason it was funded this way is that Larry H. Miller had a vision for this project. He was aware of the work that Dean Jesse had done in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s to recover and publish Joseph Smith’s papers in various publications, and he was eager to see that continue. Larry felt, he said, prompted by the Lord to come forward with an offering of support. So, we are very, very much indebted to Larry and to Gail and their family for the tremendous amount of support they provided to the project for many, many years.

And I think that’s the short version of the story. Hopefully, that’s helpful.”

Audience Member:

“Yeah, how’s Ron doing?”

Matt McBride:

“He’s hanging in there. He’s doing okay. Ron—oh, I apologize, I didn’t repeat the question. The question was about Ron Esplin, who is one of the key early members of the project team and kind of a driving spirit of the project for many years. Ron is doing okay. We still talk to him. He’s spending a lot of his time working and focusing on scholarship related to Brigham Young through the Brigham Young Center. You may have noticed that the first volume of the Brigham Young Papers—one of the volumes with some of his journals—was published last year. That effort is something Ron oversees, with the support of scholars, some of whom are on our Joseph Smith Papers team, and some of whom come from other institutions or backgrounds.”

Scott Gordon:

“Next question, right here.”

Audience Member:

“What’s the future of the project? And perhaps, what’s the future of the team you’ve assembled to work on it?”

Matt McBride:

“That’s a great question. As I suggested in my remarks, many members of the team are working on building a layer of scholarship that grows out of the foundation of the papers right now—scholarship that we think and hope will be helpful to Rick Turley as he works on his biography. There are some ongoing discussions with Rick about that.

Many members of the team are busily engaged in continuing to figure out what it looks like to build on that foundation. When we released the final volume of the project, our advisors, Elder Bednar and Elder Gong, said something at the press event that stuck with me. They said, ‘This is chapter one—you ain’t seen nothing yet!’ And I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, what’s chapter two?’ That’s something we’re working on and thinking about right now.

Aside from further work on Joseph Smith’s life, our team is also engaged in other approved projects within the Church History Department, and we will continue to publish important works of historical scholarship going forward. Two of them will come out next year. One is a rather unique history that tells the story of the Young Women’s organization within the Church. It’s a really remarkable work of scholarship by some of our women’s history specialists.

Then, as Elder Snow announced several years ago, we’re working on preparing the William Clayton journals from Nauvoo for publication, and we hope that will appear next year as well. There are other things down the road, but we’re busy!”

Audience Member:

“There’s clearly some difference between how the Church is handling history now versus how they handled it in the past. Can you shine a light on what differences there might be, say, between Arrington’s team in the 1970s and what you’ve been doing in the last 20 years? Is it more than just professionalism? Is it the size of the team, record access, things like that? I’m curious.”

Matt McBride:

“That’s a great question. You captured some of the really important things I might have shared. It’s certainly about the size of the investment in staff and historical expertise, which I think we owe in part to Larry and Gail Miller and their efforts to ask, ‘What can we do to help this particular project go forward?’

The historical profession has also changed a lot since the 1960s and 70s, just as those decades were very different from the early 20th century. The kinds of questions you ask, the kinds of sources you interrogate, and the approaches you take are different.

So, we’ve got a really spectacular, well-trained, but somewhat younger team in terms of their training and approach than perhaps what Leonard Arrington and his team might have taken. And then, yes, I think there’s been an increasing willingness and amount of support and encouragement from Church leaders. Sometimes that takes the form of expanded access to records, as you suggested. In other instances, it’s just our ability to examine everything with the Joseph Smith Papers project and do a fully open publication.

There are a number of things I’d point to as differences, but what Leonard and his team did was an incredibly important foundation. All of us consider our work to be building on what he did.”

Scott Gordon:

“Where’s the mic headed next? Right in the back, okay.”

Audience Member:

“How has this influenced thoughts about future prophets or their papers? For example, the Russell M. Nelson Papers—has this influenced how records are kept for future generations, or informed how they might better keep a record? I’m curious about that.”

Matt McBride:

“This is a really good question, and you touched a little nerve there. If we had archivists here, they’d be twitching. It’s actually something we are worried about all the time—what does the record look like? Records are kept differently in the 21st century than they were in the past, if you haven’t noticed.

We often wonder what that will look like, and we spend a fair amount of time thinking about it. As a department, we’re working with other Church departments and Church leaders at various levels to make sure there’s a records plan in place that will be adequate for the future.

And I think, implicit in your question is, ‘What about the papers of other presidents?’ The Brigham Young Center is doing a fantastic job working their way through the Brigham Young Papers right now—that’s a project we didn’t decide to take on. They’re brave souls! The Wilford Woodruff Foundation has also done a phenomenal job with the Wilford Woodruff Papers. They’re working on an open and accessible publication of his papers, which we’re excited about and enjoy watching. We use their work in the Church History Department. So, in some ways, those are another kind of outgrowth or legacy of the papers. We were kind of on the sidelines as cheerleaders for those projects, but we’re very invested in them and excited about them.”

Scott Gordon:

“Who has the mic next? Oh, over here.”

Audience Member:

“You said Joseph Smith scuffed up a tax collector. Did he have it coming?”

Matt McBride:

“(Laughing) I don’t know! That’s a tough question to answer. Joseph certainly thought he did. But, judging from the way Joseph behaved in the wake of that incident, it appears that he thought better of it and decided that whether the tax collector had it coming or not, Joseph needed to maybe not respond quite the way he did.”

Scott Gordon:

“So, he submitted to due process.”

Matt McBride:

“I’m not sure where the mic is now. Do you want me to call on someone? Oh, over here.”

Audience Member:

“You mentioned two upcoming publications. I’m curious about the biography you mentioned, by Turley, as well as the teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. What kind of time frame are we looking at for both of those? Any idea?”

Matt McBride:

“Years… many years, okay. Oh, I don’t know… I don’t know about many. Wait—okay, I don’t know about many, but it’s not coming… it’s not coming in a matter of months. I’m hoping the Teachings volume could be done in the next couple of years.

And I feel bad for this side; I haven’t called on enough people over here. Maybe you—right here, this hand, thank you.”

Audience Member:

“Was there a particularly inspiring or memorable moment for you while working on the project?”

Matt McBride:

“Yeah, I shared part of this earlier. Let me help you understand the involvement of all of our historians. We are each assigned specific documents to work on, and I have this bizarrely deep expertise in a handful of documents. But those are just a drop in the pond compared to all of the material that’s there.

One of the things I’ve enjoyed over the past five years has been my role as a reviewer of the work of my colleagues. I tried to touch on this in my remarks, but one of the most powerful experiences I had was reading the last volume of the Documents series. There were moments when I felt—well, I know my life can be stressful at times, but trying to put myself in Joseph’s shoes and understand what it was like for him during the final weeks of his life—it reduced me to tears on more than one occasion because it was just overwhelming.

Another experience I’d point to is the privilege of being able to pick up the volume that contains the facsimiles of the pages of the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon. You know, we tried to make the experience of handling that volume better than someone might have had holding the pages themselves, partly because the pages have deteriorated over time and the text isn’t very legible anymore. We went to great lengths with multispectral imaging and other efforts to represent the document and artifact in an incredible way.

So, to have that book in my hands, to open it up and see those pages, and to know that I’m having an experience with an artifact that was in the room as Joseph Smith dictated the Book of Mormon and as Oliver Cowdery wrote it down—that was moving to me. If there’s one volume in the entire papers that I think you might want to invest in, it’s that book. Not trying to sell books here! But it’s maybe the closest experience you can have with what most of us here would consider a very sacred artifact.”

(Laughing)

“Oh, see? I told you I wasn’t a very good salesman! It’s Volume Five of the Revelations and Translations series. The one story I can share about it is that when we took a copy over to deliver it to the First Presidency, they picked it up and noticed how heavy it was. From what I understand, they went around the Church Administration Building to find a scale so they could weigh it. We didn’t know how much it weighed until they weighed it for us—and it was heavy. I don’t remember the exact weight, but it’s a hefty book. It’s incredible.”

Scott Gordon:

“Let’s see… maybe here, for the average Church member who doesn’t do anything more than listen to General Conference and attend Sunday School, how will the Joseph Smith Papers affect their understanding of the Church and the gospel?”

Matt McBride:

“Yeah, and my thought on that is… and I tried to point out a few things, but it influences their study of the scriptures, especially with the work we’ve done to improve the study aids around the Doctrine and Covenants. That seems like an important thing that’s going to reach a large audience of Church members.

The insights we’ve learned from the papers could come to Latter-day Saints in the form of some of these products here—some of which have been read by millions of people—and they’re deeply informed by the scholarship done for the papers. So, while the papers are a scholarly product designed for a particular audience, we’ve gone to great lengths to distill the insights and present them in a way that benefits a much wider audience of Church members.”

Scott Gordon:

“Maybe one more question. Over here.”

Audience Member:

“At what point did the General Authorities decide to open up the archives of the Church? Was there any particular event or philosophy that brought that about?”

Matt McBride:

“Well, that might be a little above my pay grade! I don’t think there’s a very straightforward answer to the ‘when’ question because there’s been an ebb and flow that’s gone on for decades. I do think the Joseph Smith Papers themselves represent an important inflection point in that story.

The beginning of the work on the papers—when the team was able to work through interesting and challenging material and publish it in a way that earned the respect of scholars—was important. The work on the early volumes of the papers ended up having a snowball effect. As we went along, there were key moments over the course of 22 years where further records and materials were made available.

So, it’s not like there was just one moment. It’s been a long story, and one that continues.”

Scott Gordon:

“Well, thank you for your questions. It’s been good to be here with you. I appreciate it.”