Summary

Dr. Janiece Johnson explores how the Mountain Meadows Massacre shaped public perceptions of Latter-day Saints in the 19th century and beyond. She examines how media, political cartoons, sensationalized narratives, and legal proceedings framed the massacre and contributed to anti-Mormon rhetoric.

The talk delves into John D. Lee’s trials, the accusations against Brigham Young, and the role of fiction and propaganda in reinforcing negative stereotypes about Mormonism. Dr. Johnson highlights how gendered critiques, polygamy, and the portrayal of Mormons as outsiders played into broader anti-Mormon sentiment. She also discusses how these misconceptions persist today, particularly in modern media like Under the Banner of Heaven.

Through historical analysis and apologetic insights, this talk clarifies common misunderstandings and false accusations, demonstrating how anti-Mormon narratives evolved over time and why some still endure.

This talk was given at the 2023 FAIR Annual Conference at the Experience Event Center in Provo, Utah on August 3, 2023.

Dr. Janiece Johnson is a historian specializing in American religious history, a researcher and instructor at BYU, and the author of Convicting the Mormons: The Mountain Meadows Massacre in American Culture (2023).

Transcript

Introducing Janiece Johnson

Scott Gordon:

Janiece Johnson is a transplanted Bay Area, California native who loves history, design, art, good food, and traveling. Dr. Johnson has a master’s degree in American religious history and theology and a PhD in American history. She has taught at BYU-Idaho and in Religious Education and currently teaches and researches at BYU. She is the coauthor of many books.

I do know we have her book here in our bookstore, and after she speaks and someone gets her lunch—well, we’ll get her lunch—she will be out in the foyer area. She can sign a copy of her book and talk to you about it at that time. With that, we’re happy to have Dr. Janiece Johnson.

D. Janiece Johnson

Convicting the Mormons

Introduction to My Work on the Mountain Meadows Massacre

Thank you, Scott. It’s good to be with you all today. There we go.

Okay, so my book came out in May, just a couple of months ago. But I have spent most of my career working on the Mountain Meadows Massacre. As a master’s student at BYU in history, I took a little bit longer on my master’s thesis because I switched topics near the end and had a few extra months before I was headed off to the next stage of graduate school—divinity school.

How I Became Involved in Mountain Meadows Research

And I needed a job. So I interviewed for a job with Ron Walker to be a research assistant. I interviewed, and he told me the job was working on Brigham Young and the Indians. That wasn’t really in my wheelhouse, and I wasn’t particularly interested in it. But I needed a job. And then I had what I thought was going to be a second interview.

And in this, it wasn’t a second interview at all. He said, “You have the job if you want it, but we’re working on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and it’s not public yet. It hasn’t been publicly announced by the Church, so you can’t talk about it.” This was not quite what I expected. But I still needed a job.

My Early Work on the Mountain Meadows Massacre

So I started working for Ron Walker. At first, they said that it was going to be four or five months, and I thought, “This is perfect.” Then I would just have a summer before I started school again in the fall. And yet, I worked for about six or eight months—six months—and we were nowhere near done.

I thought with three authors and a whole host of resources at the Church History Library and a whole host of researchers that this would be done very quickly. The book that resulted from that work was Massacre at Mountain Meadows, and it was not published until 2008. This was 2001 when it began. But as I left, I didn’t feel like I was done with Mountain Meadows.

The Challenges of Researching Mountain Meadows

And I didn’t particularly like working on Mountain Meadows. I was completely nauseated for the first few months that I worked on it. Once it became public, I could talk to people about the project, and many Latter-day Saints that I talked to kind of made me feel like we were going to find out what really happened and why it wasn’t so bad. And my response inevitably was, It’s just as bad. You can’t make this better.

But part of my initial reaction, as I was first learning, was my inability to decipher between what was real and what wasn’t—what was exaggeration and what was built up. The reality of this event is bad enough. We don’t need to exaggerate. We don’t need to expand the narrative.

My Continued Work and Dissertation

But as I began and in the years that I have spent since then, after I went to divinity school, I came back, and Rick Turley hired me to work on John D. Lee’s two trials. I became the general editor of the Mountain Meadows Massacre Legal Papers.

And so this has been central to my career. It became my dissertation, and this became my dissertation book. But this book, Convicting the Mormons, is all about the massacre—and yet not at all about the massacre.

John D. Lee’s Role in the Narrative

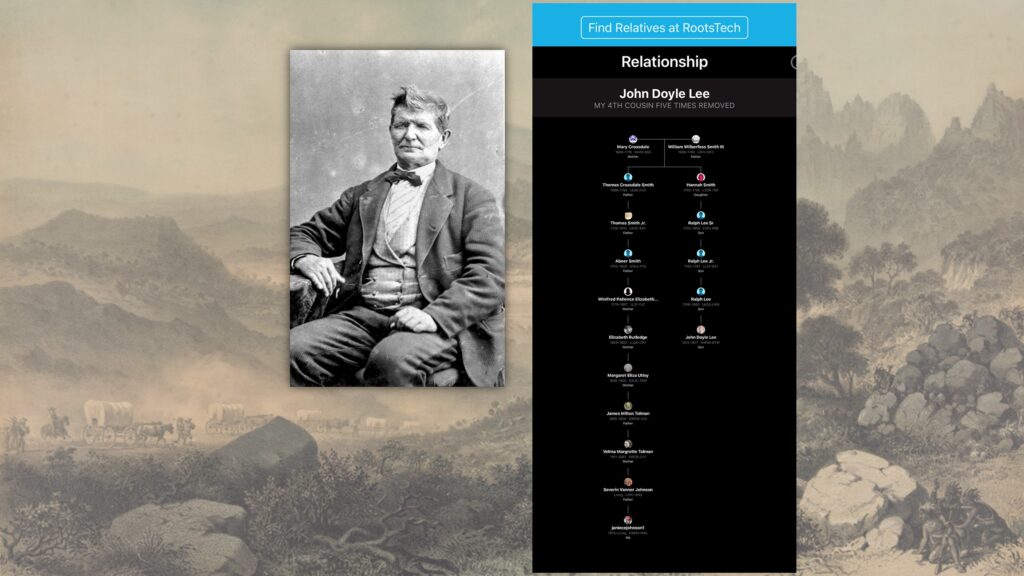

Because—and John D. Lee, this is the other element here—John D. Lee, in all prior histories, was central to what was going on in the massacre narrative. Yet the more that I got into John D. Lee’s trials and the prosecution for the massacre, the more I realized that John D. Lee wasn’t actually central to what was going on. He was guilty. He was a participant. But, what was going on politically and legally had very little and in many instances to do with John D. Lee.

Just as a disclaimer, I just—I don’t know if it’s a disclaimer—because I just found this out the same week that my book came out. FamilySearch handily told me that I was related to John D. Lee. I had no idea. I’ve been doing this for more than 20 years. I now—I’ve even forgotten—one of my fourth cousins, five times removed. So many of us in the room would probably fit in the same category, if you have any Mormon stock.

How Mountain Meadows Defined Public Perception of Latter-day Saints

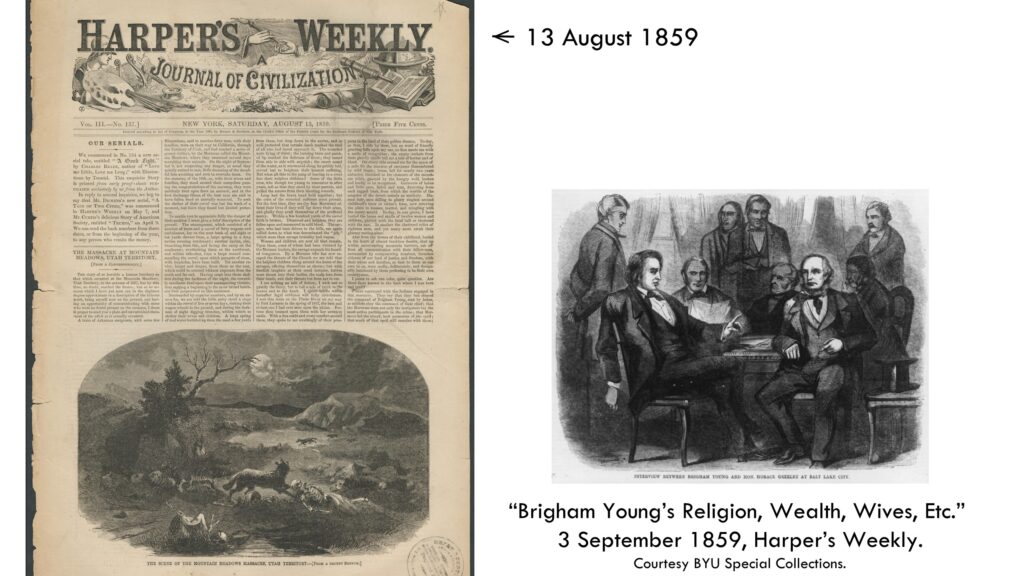

But the more that I got into this topic, the more I realized that much of the story that’s told about Mountain Meadows in the 19th century and up until today has very little to do with Mountain Meadows itself. But yet, Mountain Meadows would color everything that Americans and many onto the continent, into Europe, would know about Latter-day Saints in the 19th century.

This is Harper’s Weekly, a Journal of Civilization. This is August of 1859. This is the first time that Mountain Meadows gets front-page attention. This is two weeks before Horace Greeley’s interview with Brigham Young is also on the front page of Harper’s Weekly. So everything that people learn about the Latter-day Saints in the 19th century comes through this lens or is colored by what happened at Mountain Meadows.

The Role of Visual Culture in Shaping Perceptions

Today, I know we’re right before lunch, and so I want to make sure that if there’s any—if we’re getting a little bit antsy—that we have plenty of visual things to look at. So we’re going to walk through some of the visual culture which makes up this American idea of how this narrative is received in the 19th century.

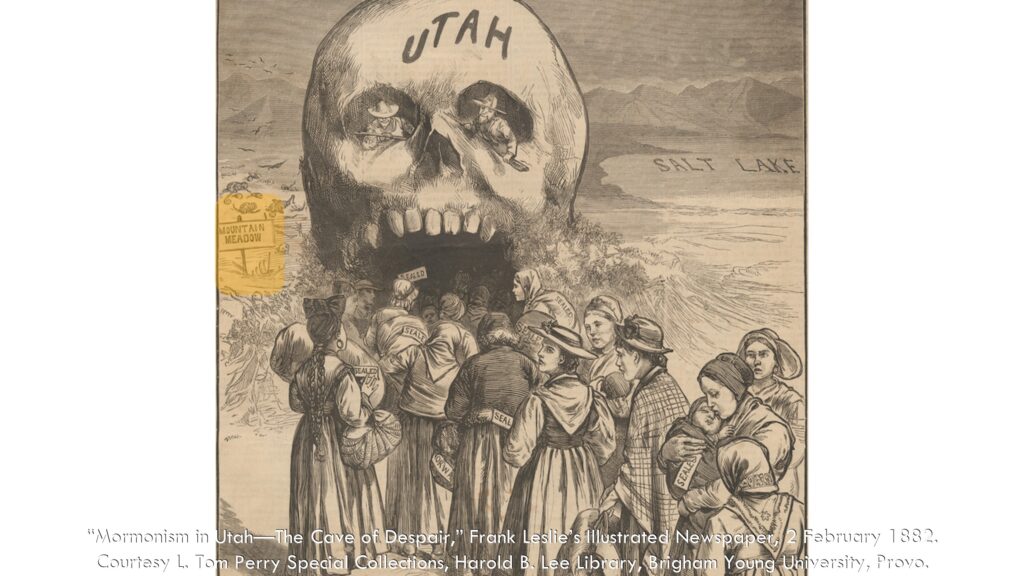

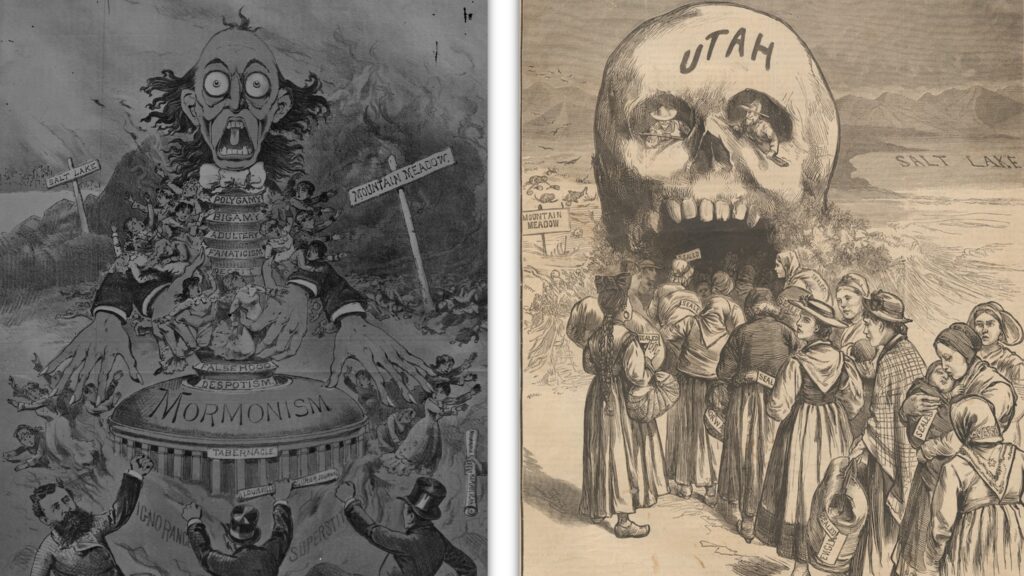

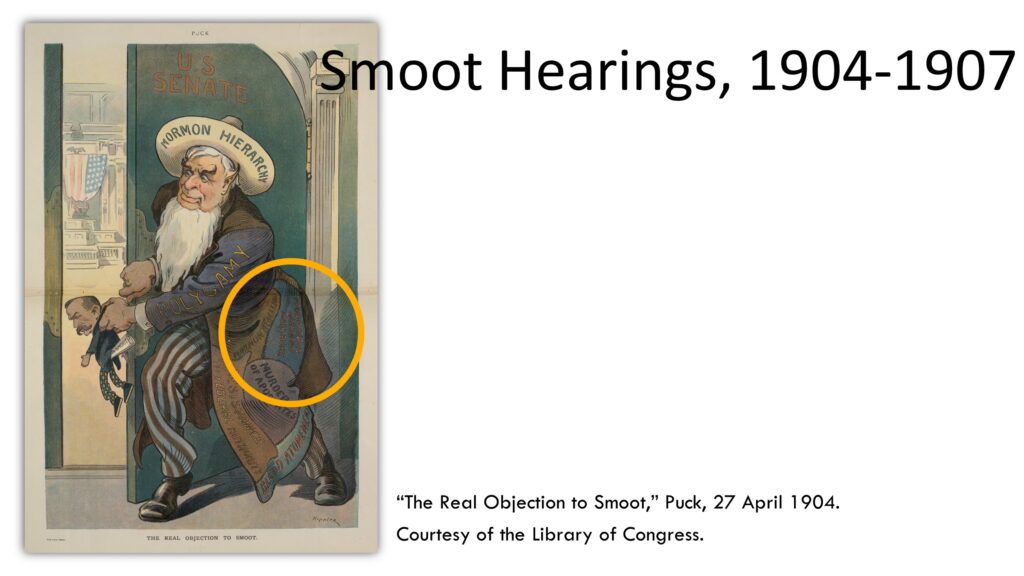

This very striking political cartoon was on the front cover of—is on the front cover of my book. Some of you may have seen it before, from 1882. Mormonism in Utah: The Cave of Despair. So we have women dressed in kind of their traditional dress for many different countries with tags on them. Some of the tags say where they’re from. I think there’s one woman who’s from Norway. But most of them say sealed.

Anti-Mormon Imagery and Fear-Mongering

So this—this is perpetuating this idea that Mormons are gathering women from four corners of the earth and bringing them to the Cave of Despair. William Jarman, who was a prolific anti-Mormon pamphleteer in Great Britain, stole the same image and just said, Welcome to Hell.

This—this is what this idea of Utah was. The skull marked Utah, with two very menacing Mormon men, and the two eyes. And then this literal signpost to the side of Mountain Meadow, Plural Marriage.

Marital practices may or may not be enough to convince people that there is something untoward about the Latter-day Saints, but Mountain Meadows elevates the danger of Latter-day Saints, elevates the danger of Mormons.

Distinguishing Between Perception and Reality

And I’m going to use Mormons freely through this, because this is how most Americans understood. And in my book, they try to distinguish. I use Mormon when we’re talking about perception, and Latter-day Saints when we’re talking about what actually happens.

But Mormons—this elevated the threat of Mormons to a real physical threat, not just people with curious marital practices. But we have this very on-the-nose reminder of Mountain Meadows.

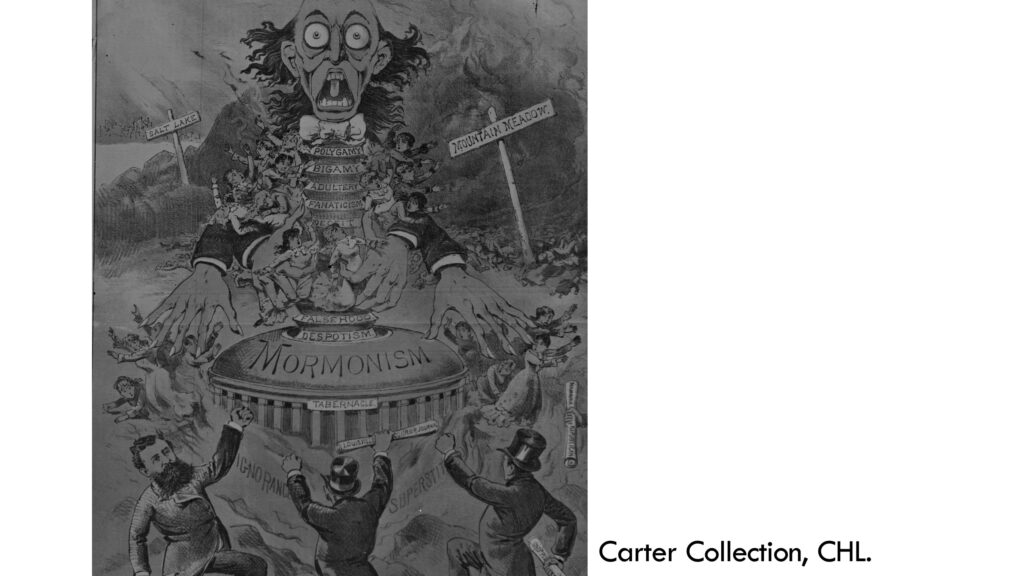

Now, my favorite political cartoon—which I—I wanted to be on the front cover—but my editor said this was a little more complex than the last one to understand.

The Creepy Patriarch in the Box: A Critique of Polygamy

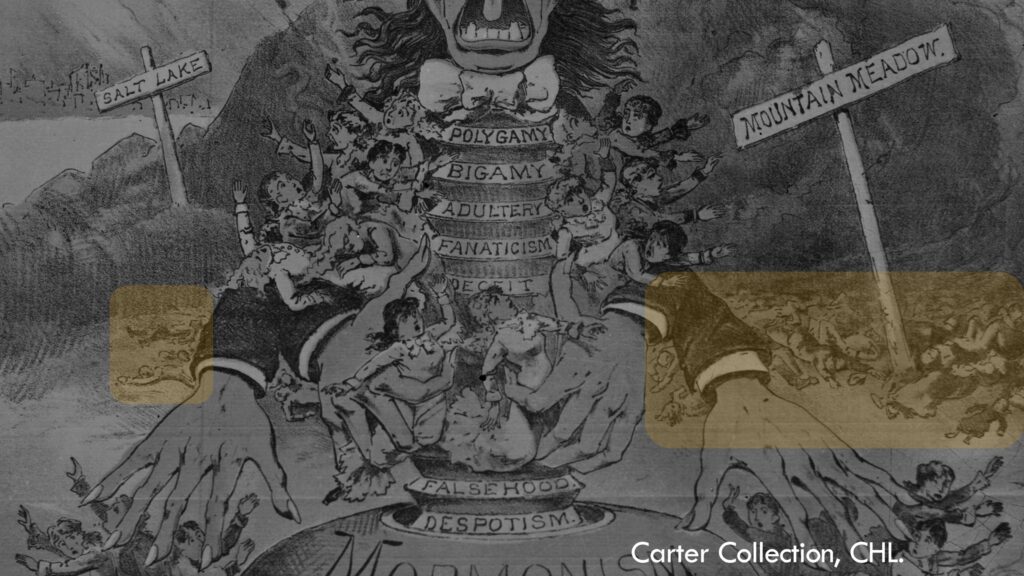

But we have this—what I call—creepy patriarch in the box. He is sprouting out of the Tabernacle, which, of course, prior to the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple, this is the most well-known Mormon building. The folds of his neck say polygamy, bigamy, adultery, fanaticism, deceit. He has women falling out of his neck, and his elongated polygamous grasp is reaching for more women.

So very definitely, this is a critique of polygamy, and polygamy is always the lightning rod. But to the side, we have a specific reminder again—a literal signpost reminding us of Mountain Meadows. Towards the bottom, we have newspapermen who are stamping out ignorance and superstition that seem to be protecting the Tabernacle.

Hidden Details in Anti-Mormon Imagery

Now, in the process of preparing images for the book, I finally got a high-resolution version of this image. And for the first time, I noticed that not only do we have this signpost again, but we actually have literal dead bodies around the signpost. And those dead bodies continue all the way behind the patriarch in the box to the other side, again elevating that threat of Mormonism to a real physical threat. And we’re going to see this continually and consistently in the 19th century.

John D. Lee’s Trials and the Public Spectacle

When John Lee goes to trial, he has two trials—one in 1875, which resulted in a hung jury. There is not actually anyone at the trial who can testify to Lee killing anyone. Lee was guilty. He was definitely guilty. But they didn’t have evidence of his guilt in that first trial, which resulted in a hung jury.

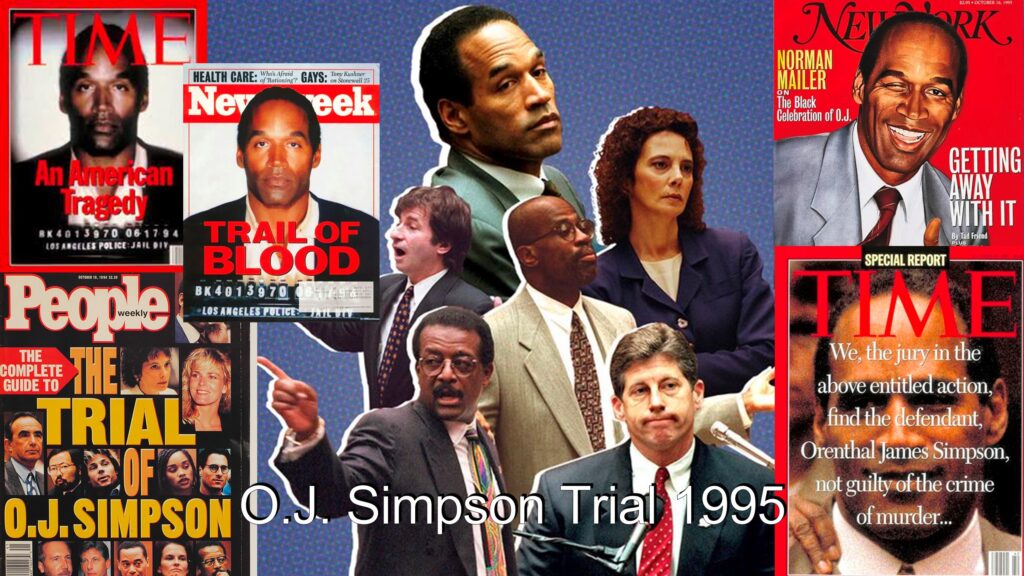

But Lee’s trial was reported all over the country. If you were in a small town, you knew about John D. Lee’s trial. If you were in a big city, there were headlines with John D. Lee’s trial. The only comparison in my lifetime that I can compare this with is O.J. Simpson’s trial.

I came back from a mission—I had very vague memories of being in Argentina and hearing something about the white Bronco and O.J. on the run. Came back and was a BYU student, and everyone’s watching the trial. And we can see—we have newspaper headlines, we have magazine headlines, we have special reports and commemorative issues of magazines that people can buy to commemorate this event. John D. Lee’s trial was that for the 19th century.

The Relationship Between Trials and Popular Narrative

This is Lee and his attorneys in the first trial. But as I began to look at this, my book compares the relationship of the trials and the official prosecution for John D. Lee and its relationship with the popular narrative that continues to spin about Mountain Meadows.

And in general, my argument is that, though both the trials and the popular narrative have an interdependent relationship, sometimes elements come up in the popular narrative first and then later show up in the trial. Other times, things come up in the trial and then later show up in the popular narrative.

What the Popular Narrative Focuses On

But the elements that become fixated on are not actually elements that yield a lot of information about the truth of what happened on the fields on that day of the massacre or leading up to that horrific massacre. But they actually tell us more about places where Mormons were perceived to conflict with Americanness or civilization.

And so this book, unlike other Mountain Meadows books, I am not following the straight narrative of the massacre, but looking at these different ideas—these different places where Mormons breach acceptable standards of Americanness.

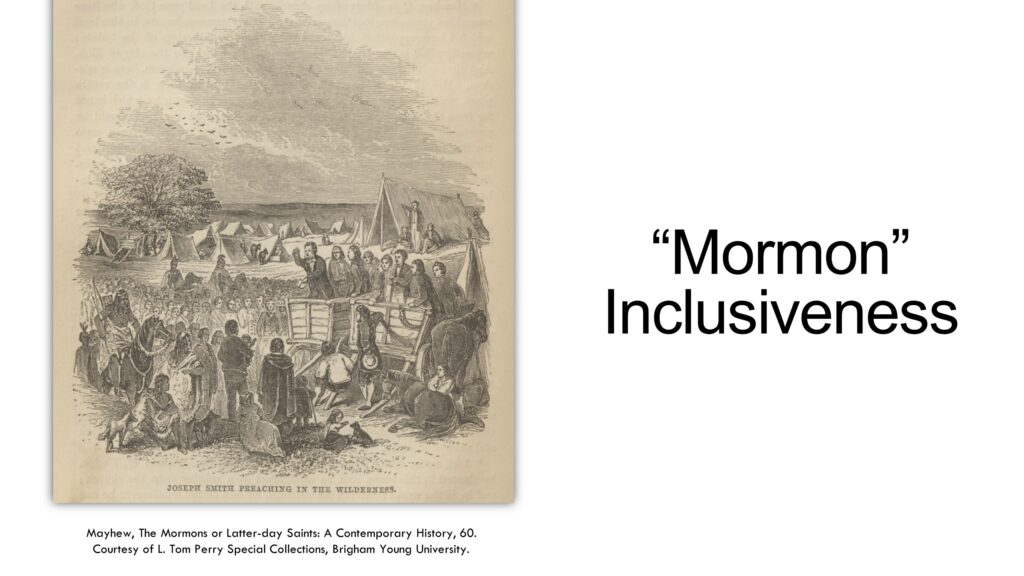

This image is supposed to be from Jackson County, and we have Joseph Smith preaching. The description talks about that. There were a number of free Blacks and Native peoples in attendance. This was considered a negative thing in the 19th century—that Latter-day Saints were inclusive and were bringing people in.

But from the publication of the Book of Mormon and the elevated position of Native peoples that we can read from the Book of Mormon—though Latter-day Saints were not always living up to that ideal in practice—we have these accusations that Mormons were too inclusive.

And one of them, that is consistent long before there ever was a Mountain Meadows, was this idea of Mormon savagery or that Mormons and Native peoples were united.

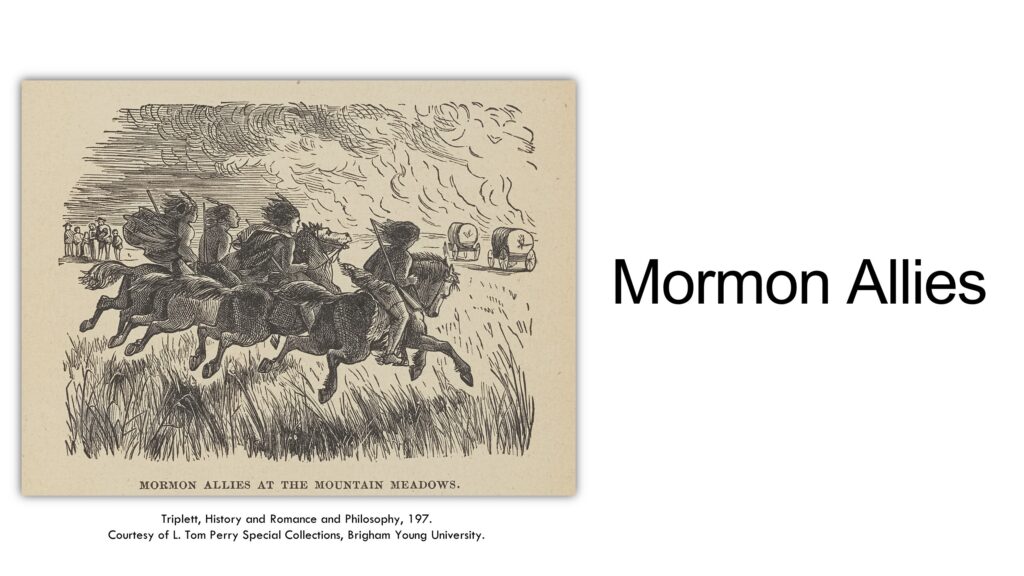

Mormons and Native Allies at Mountain Meadows

These are Mormon allies at Mountain Meadows. That rather than civilization, where savagery is met with opposition, Mormons wanted— And this, of course, is a caricature of Native peoples in the 19th century—but that Mormons brought in and were allied with the Indians.

We get hints of this in Kirtland, when we have descriptions of some of those extreme spiritual events that happened around the dedication of the Kirtland Temple. And they are described as— that there is Indian warfare or Indian spiritual practices in evidence.

Fear of a Mormon-Indian Alliance

When the Saints are in Winter Quarters, a woman comes to Warren Foote and says, “I’ve heard about the Mormons and the Indians getting together, and they’re going to kill all the settlers on the frontier.” And Warren Foote says, “Yeah, she’s going to be waiting a long time.” Warren Foote did not think that was possible. But in 1857, we see that reality.

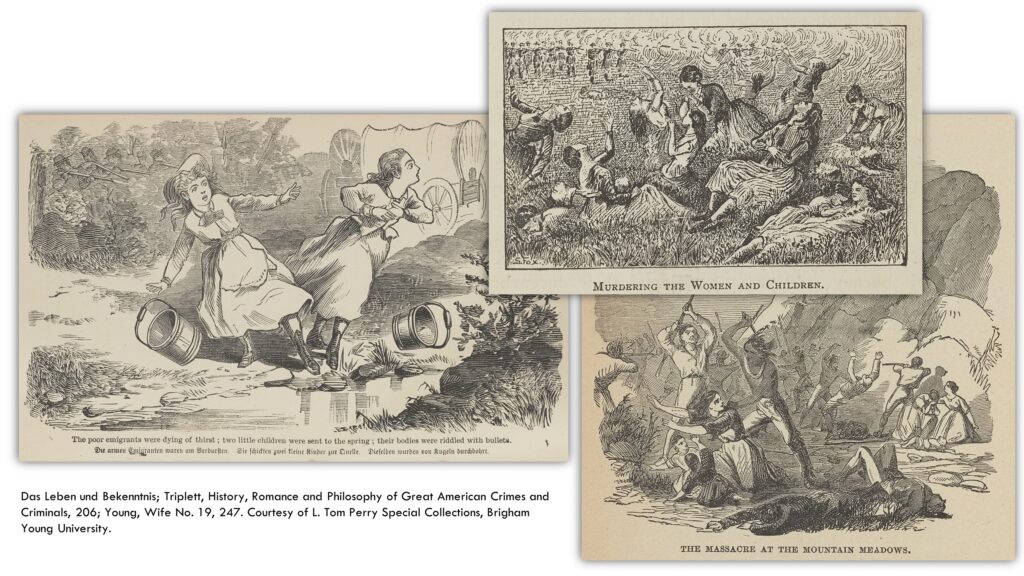

Images of the Massacre

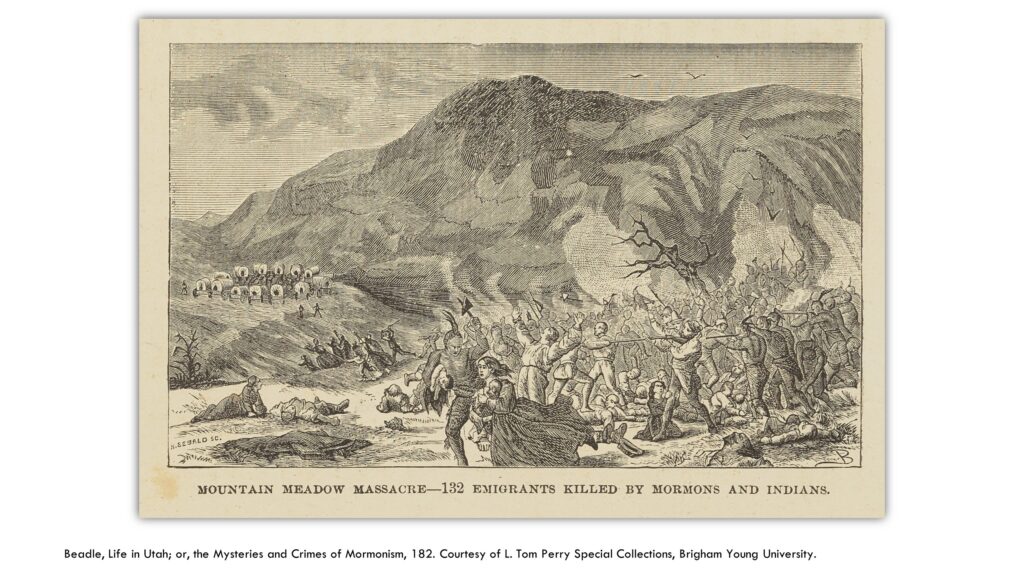

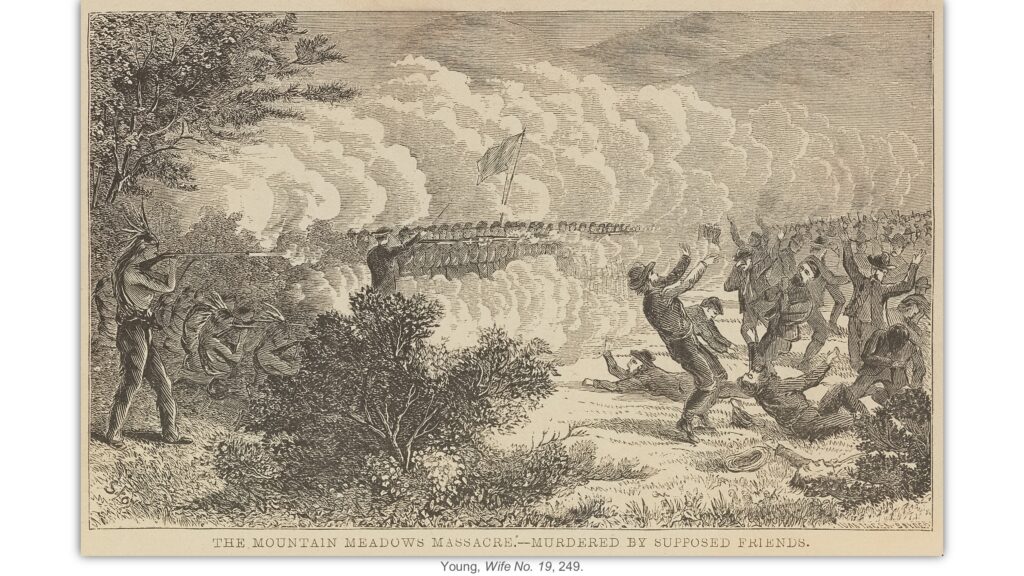

Images of the massacre. In the 19th century, none of these narratives of the massacre— all of them include Native peoples.

John D. Lee’s Plan to Blame the Paiutes

John D. Lee, specifically—he goes and recruits Paiutes to help. And John Lee and Isaac Haight’s plan from the very beginning was that they were going to blame it on the Indians.

So again, one of those times when we did not live up to our theology. John D. Lee is a farmer to the Indians. They have proselytized to the Paiutes. They have baptized Paiutes. And here they want to blame the massacre on the Paiutes. That is the plan.

Depicting Mormons as More Savage Than the Indians

In much of the literature that talks about the massacre itself, it says that Mormons were acting like Indians after Mountain Meadows. The Mormons are now more savage than the Indians. They are not like the Indians. They haven’t just allied themselves like the Indians, but they are now more savage than the Indians.

And we get some later accounts that remove the presence of the Paiutes entirely. It is just white Mormons who have dressed themselves up as Native peoples.

The Idea of White Civilization in the 19th Century

All of this rotates around an idea of white civilization. Civilization in the 19th century—it wasn’t yet a given that the United States would go from sea to shining sea.

Those ideas of Manifest Destiny are still being inculcated. And this idea of civilization was always inherently white. If you were white, there was a place for you in American civilization. If you were not, there was not.

The “Vexed Whiteness” of the Mormons

Now, Mormons—there, like Spencer Fluhman talks about—the vexed whiteness of the Mormons. Paul Reeve’s work does a lot to help us unpack and think about the ways that Mormons were considered not white.

However, interestingly, in the Mountain Meadows narrative, it functions very differently. In the Mountain Meadows narrative, Mormons looked white, but then their behavior did not match up.

The Symbolism of the White Flag and the American Flag

William Carey, who is the lead attorney—the lead U.S. attorney prosecuting John D. Lee—when he opens his court case, he talks about two flags.

He talks about a white flag, which is known amongst all nations. And he talks about an American flag. Now, every other account will talk about a white flag when the Mormons go up and try to—John D. Lee tries to—get the immigrants to give themselves up after they’ve been under siege for many days. He has a white flag, and they are duplicitous.

Lee, trying to come under that white flag of truce, and lead—I think this is a direct quote from the trial transcripts—but lead those immigrants cruelly away to their death. But as William Carey is presenting this for the court, he also talks about how they have an American flag. This is the only place we get it.

We don’t actually have any witnesses. We don’t have anyone else who mentions them having an American flag. I don’t think they had an American flag, but that is the way he wants to set it up. They’re presenting themselves as Americans. They have white skin. They look like they belong. Yet, they’re not. That white skin shields something horrific and duplicitous.

The “Mormon Smile” and Perceived Duplicity

Now, today, we still get some of the remnants of this. Katie Lofton, at the Mormon History Association a couple of years ago, talked about the Mormon smile—that there is something sinister, duplicitous, hidden behind all these smiling Mormons.

But we get that same—we get precursors to that kind of idea here. Mormons look white. They look like they belong in contrast to those people of color whose skin signals to us that they do not belong.

But yet, Mormons aren’t part of civilization. They have escaped civilization.

Parallels with Anti-Catholic Sentiment

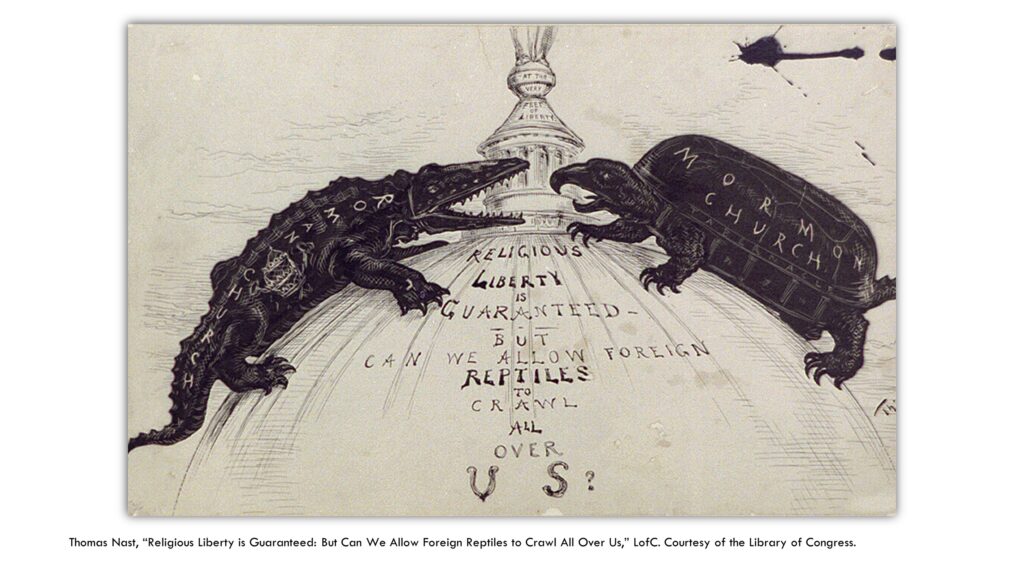

Now, much of what we get—there are lots of similarities with the anti-Catholicism that is happening at the same time. Both the Mormons and the Roman Catholics are attacking the foundations of liberty.

These—these foreign reptiles, as Thomas Nast calls them in this famous political cartoon.

Depictions of Civilization and Where Mormons Fit

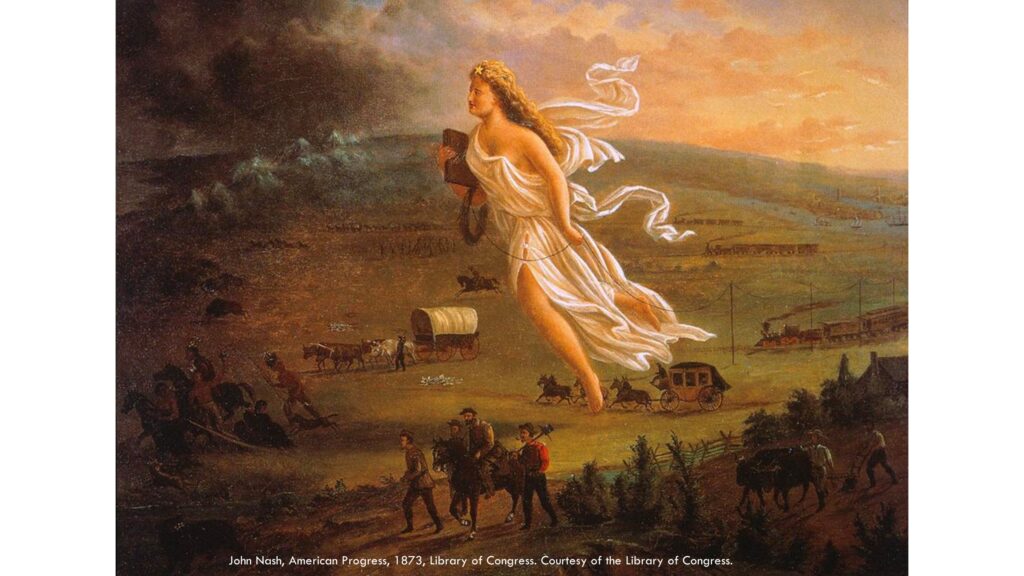

But this idea of civilization is a very powerful idea. Here we have John Nash’s depiction of Columbia bringing—so this symbol, this feminized symbol of America—bringing light to a dark frontier.

If you notice, she has a telegraph cable in her hands, and she—and the railroad is following closely behind. And we have wagons bringing light to a dark frontier.

Now, Latter-day Saints—where would we put ourselves? We’ve just had—if you’re in Utah, we’ve just had—the Days of ’47 celebration. Where would Latter-day Saints place themselves on this? Smack dab in the middle. Right in those wagons, bringing light to a dark frontier.

Yet most Americans would see this image and would say, No. The Mormons are ahead.

Mormons as Outsiders to Civilization

The Mormons tried to escape to the darkness. The Mormons are on the edge with the Native peoples. So they have tried to escape the light of civilization, and their Mormonism has taken that civilization out of them.

Gender Ideals and American Identity

Gender ideals also—what? Well, Jacob Borman, who is the attorney—the federal district court judge who presides over John D. Lee’s two trials—as he instructs the jury, he says, I want you to be men.

There is this assumption that one could not be Mormon and be an American man.

Now, gender ideals in the 19th century, as well as gender ideals today, are very slippery. What one person could do could be considered manly, and another person—doing something very similar—could be considered unmanly. Then—just, just like today.

The Depiction of Mormon Men and Gendered Narratives

But think about those two political cartoons we looked at at the beginning and how this depicts Mormon men. The narrative of both polygamy and then reinforced with the Mountain Meadows narrative shows us that Mormon men are not manly. They are not true American men.

We actually have, in the closing arguments given by Robert Baskin, who was the assistant U.S. attorney, he says Mormon men give up their manhood when they enter the temple and pledge their allegiance to another man—a man they call a prophet.

But it was impossible for someone to be both Mormon and an American man.

Images of the Massacre are Highly Gendered

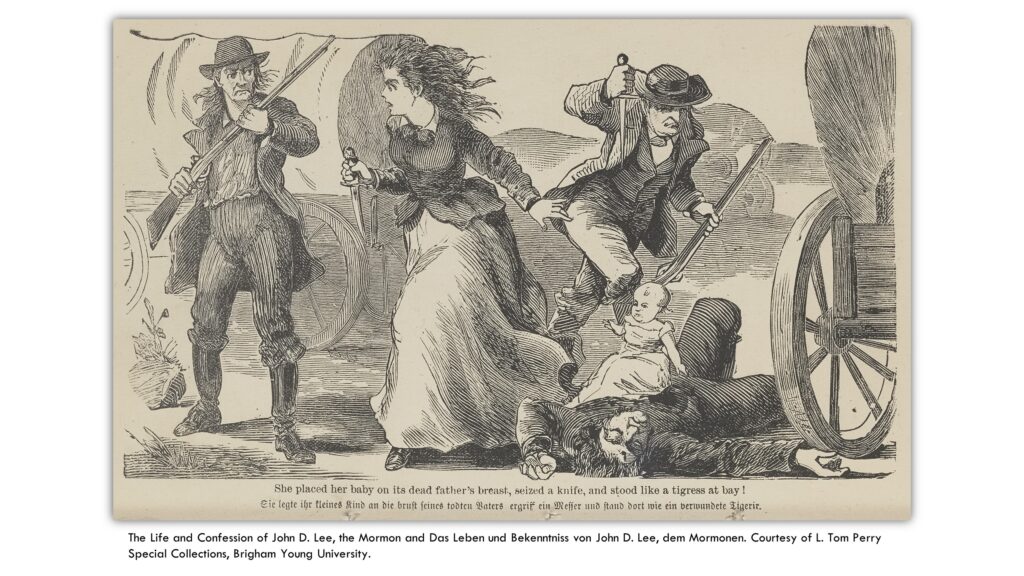

And with this, many of these images of the massacre are highly gendered. So we have lots of focus, of course, on women and children—and the killing of women and children.

There are two girls who show up in the trial testimony, and those two girls become a central role in many different retellings of the massacre.

The Portrayal of Mormon Men Forcing Women into Male Roles

But we also have this idea that not only are Mormon men not protecting women and children, but they are also making women act as men.

In this instance, this is one of the immigrant women, because Mormon men have killed her husband, and she has to be the one to defend her family. She is the—I think she’s called the tigress—but defending her family against these despicable Mormon men.

Mountain Meadows as a Multi-Purpose Narrative Tool

And then we have themes of despotism and theocracy. Mountain Meadows—the story of Mountain Meadows—really becomes like a Leatherman knife. It becomes a multi-use tool. Whatever your concern is about the Mormons, Mountain Meadows will offer you something to demonstrate that Mormons don’t belong.

And one of the greatest successes, I would argue, of John Lee’s first trial was actually pinning the massacre on Brigham Young.

Framing Brigham Young as Responsible

Robert Baskin, one of the U.S. attorneys—will—and they do not, they don’t mention Brigham Young’s name, only very infrequently. They talk about leaders quite a bit and talk about how they’re going to be able to trace responsibility for the massacre to where it belongs.

Now, knowing what they’re talking about, they’re talking about local leaders.

And there is certainly guilt there. The massacre would not have happened were it not for Isaac Haight. Were it not for him pushing around the consensus of the council, both in Cedar City and then in Parowan.

But the way that the U.S. attorneys frame this is that they leave it open, and newspapers take it and run with it very quickly.

How the Narrative Shifted to Brigham Young

Whereas pre-John D. Lee’s first trial—pre-1875—we have a couple of people making very quick, kind of minor mentions—maybe Brigham Young is involved, and then nothing happens because there’s nothing to connect Brigham Young to the massacre.

After John D. Lee’s first trial, Brigham Young is now responsible for the massacre. Brigham Young ordered the massacre.

The Fabrication of Brigham Young’s Revelation

In Robert Baskin’s closing trial argument, he will actually say that Brigham Young received a revelation that the massacre should—that this group of immigrants should be slaughtered through a revelation.

And the source of his information about this revelation is—oh gosh, I don’t know what just happened—is C. V. Waite’s 1866 anti-polygamy book, The Mormon Prophet and His Harem. She is the first person to suggest that Brigham Young receives the revelation. And this ultimately becomes part of the narrative.

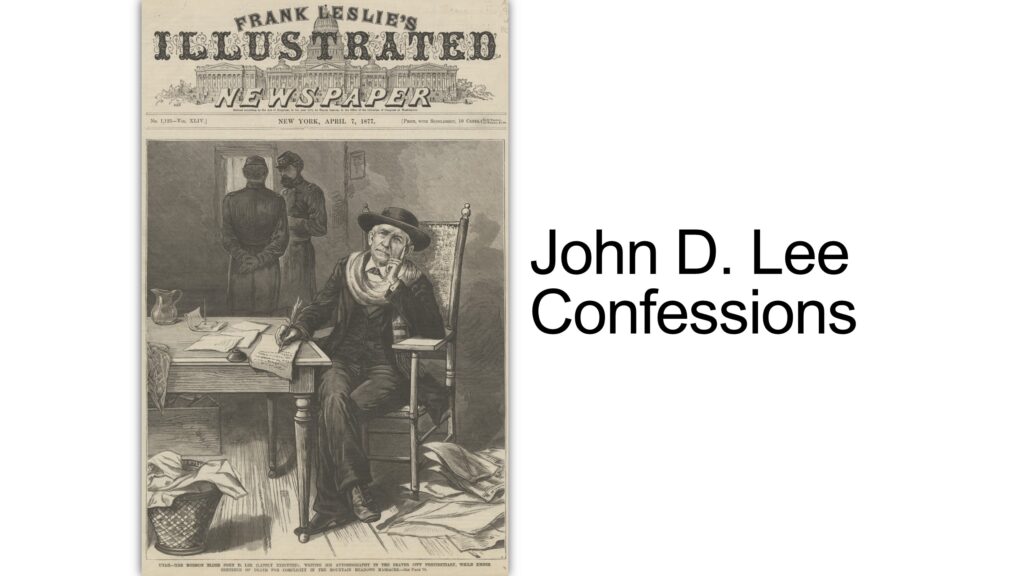

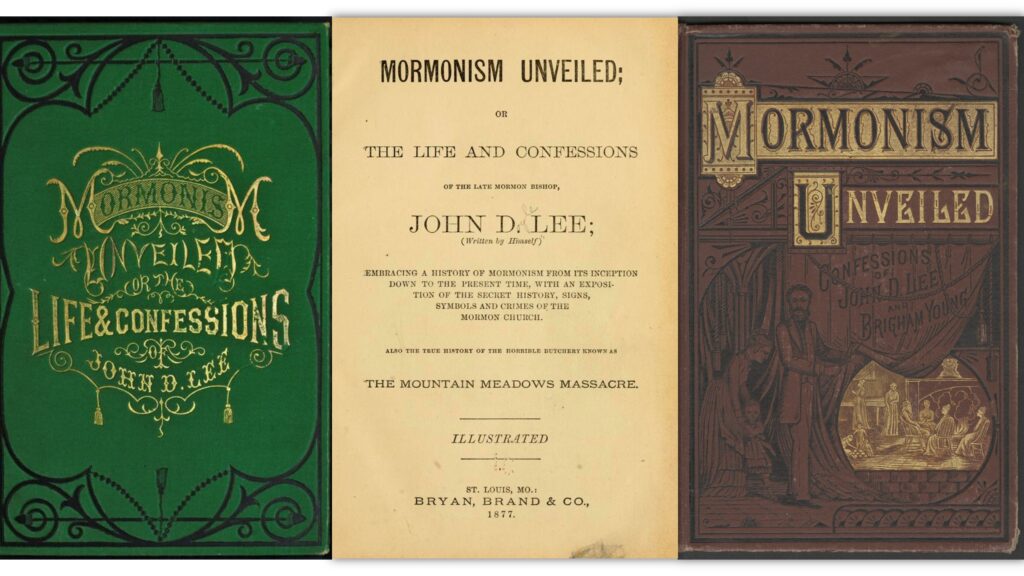

John D. Lee’s Confessions and the Selling of His Story

John D. Lee, in the last months of his life, is writing his confessions. He is in indigent circumstances. His attorney, William Bishop, has been trying to encourage him to write down his life because Bishop wants to sell it.

We have multiple people—Jacob Borman, who is the trial attorney, wants to sell a transcript of the trials. He thinks he can make money on it.

Frederick Lockley, who is the Tribune reporter who was there at both of John D. Lee’s trials, actually writes a swashbuckling romance that rotates around the Mountain Meadows Massacre—that he also thinks he can sell.

The Sensationalism of John D. Lee’s Confessions

But William Bishop selling John D. Lee’s Confessions is the most profitable source. But he needs it to be more sensational than it is. And you’ll have to go to the book to actually look at some of the analysis of John D. Lee’s confessions.

But it’s very clear today that this is not just John D. Lee. The Ogden Standard, when John D. Lee’s Confessions came out, called it ‘a little Lee and a little lawyer’. It is highly edited by William Bishop to be more sensationalized.

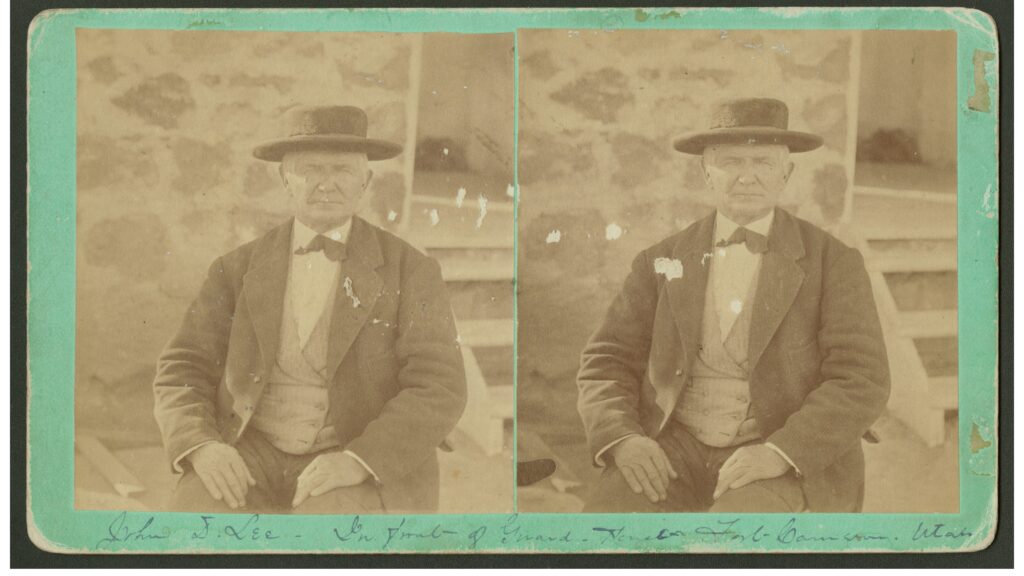

John D. Lee as a Pop Culture Icon

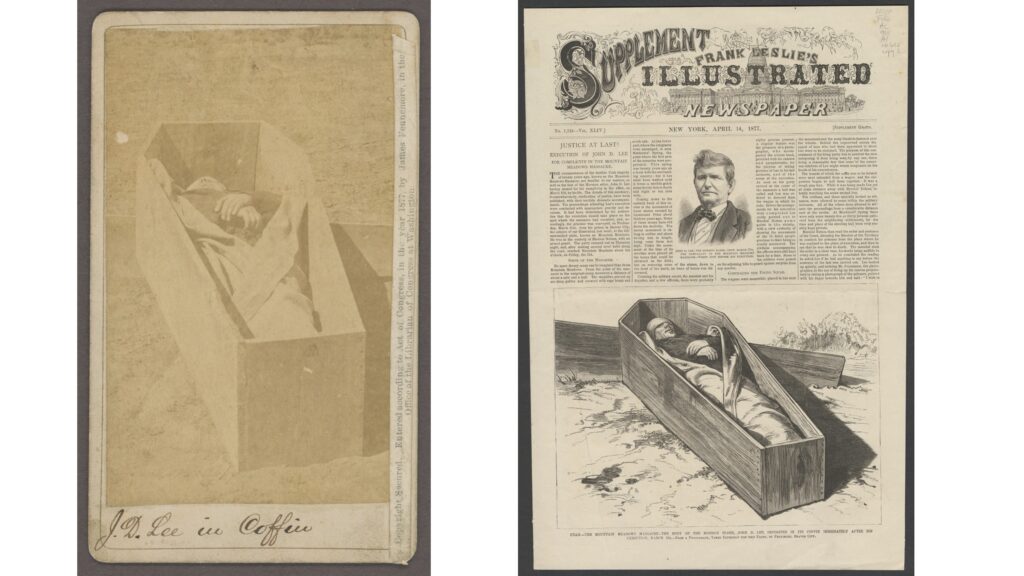

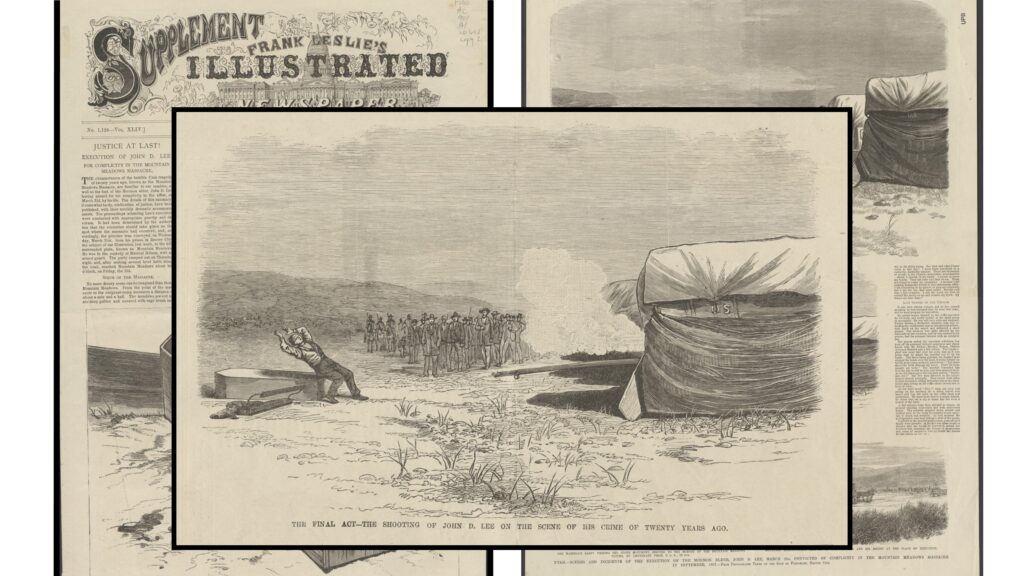

I’m just going to show a few of these images, but I want you to notice what kind of picture this is of John D. Lee.

This is shortly before his execution. He is at Fort Cameron, where he’s been held. But this was a cabinet card. Cabinet cards were collector’s items. This becomes part of this popular culture.

We have an actual image of John D. Lee after five bullets ripped through his body and he is in his coffin.

We have a special supplement issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. They couldn’t yet reproduce photographs, but they could engrave them and produce special issues so that everyone could see them.

So you can either buy the cabinet card, or you can buy the special supplement issue.

Mountain Meadows and the Reed Smoot Hearings

When Reed Smoot goes before—he is set up to try and question whether or not he can go to Congress.

Mountain Meadows doesn’t come up until we get to the very last dying breath of these efforts in 1907. We have a Tennessee senator that brings up Mountain Meadows.

Kathleen Flake, historian of the Reed Smoot hearings, says it didn’t really affect the hearings. However, each night the senators could go see a Wild West show that retold the story of Mountain Meadows.

We had a brand-new edition of John D. Lee’s Confessions, which again—

Mountain Meadows in Modern Media and Changing Narratives

And the—the narrative of civilization that focused these stories in the 19th century has changed quite a bit today. The epilogue of my book goes to the present day. I actually watched the last episode of Under the Banner of Heaven and had to write a couple of paragraphs and sent off my manuscript.

But the grammar of civilization has changed. Many of these elements and these themes that we see throughout the 19th century and early 20th century continue today. And that idea that behind that friendly exterior is something nefarious and something duplicitous stays with us. That Mormon men are dangerous.

We are still living with some of the elements of this narrative, though much has changed in the world since 1857, when these stories began being told.

Thank you very much.

Audience Q&A

Q&A Transcript with Janiece Johnson

Scott: So I grew up in my home with a copy of The Confessions of John D. Lee on our shelf. And I had a member of our ward who actually had a writer, someone at school who suddenly showed up at church, and I said, “What are you doing here?”

I said, “Well, I’m a Lee, and now the Church is dealing with the Lee family. And so we decided to come back,” which I thought was interesting because I was in the 70s.

So, have you come across any of the accusations that Brigham Young had anything to do with ordering the massacre? Some critics claim this was somehow connected to the vow some people made to avenge Joseph Smith’s blood. Can you speak to that?

Janiece: Yeah. So there—there is no contemporary evidence of that. We have lots of The Tribune. If you don’t like The Salt Lake Tribune right now—I actually really like The Salt Lake Tribune—but in the 1870s, it was a very different animal.

And in the 1870s, you’ve got all sorts of accusations, but all of the accusations of Mormonism are kind of—kind of swirled together. But—but there was not evidence in 1875 or in 1857 that Brigham Young ordered it.

Will Bagley wrote his book, Blood of the Prophets, which was published in 2002. And he was certain that Brigham Young ordered the massacre. He believed that Brigham Young, meeting with Native leaders from southern Utah on the 1st of September, was the smoking gun—that he told them to go, inexplicably, to go and pick out this emigrant train and to—to slaughter them.

But Massacre at Mountain Meadows demonstrated that the earliest that any of those Native leaders left Salt Lake was September 8th. And that’s simply—that’s not enough time to get back to southern Utah to make those 300 miles to southern Utah by the 11th.

And B, the massacre had actually already—the lead-up to the massacre was already underway by September 8th. So to—to put credence in those assumptions, you have to—there’s—there’s not the information that there is today. To get a runner to—to Brigham Young takes three days if you’ve got multiple horses to ride.

You have to believe in all sorts of conspiracies to—to make that an actual thing. But I—but I think that this tells us something about just how effective fake news is, because the narrative shifts in the first trial, and by the time—so John D. Lee’s first trial is in 1875.

By the time that Brigham Young dies in 1877—almost two years and a month later—the narrative has shifted. And half of—not every obituary of Brigham Young—but at least half of the obituaries of Brigham Young include that he ordered the Mountain Meadows Massacre. That in those two years, that narrative shifts entirely.

And we still have that narrative today, totally without evidence. And—and it is—Robert Baskin, who is arguing that—I mean, his closing argument—this is a ridiculous six-hour diatribe against Brigham Young.

But later on, when he becomes friendly again with the Latter-day Saints, he’ll say, “Yeah, we didn’t have any evidence that would tie Brigham Young to it.” But he was very persuasive, and his—his arguments were very effective.

Scott: Interesting. So here’s a question. You mentioned accounts that claim no Paiutes were present, but Mormons dressed as Indians. Is that credible? There were no Paiutes involved, or—?

Janiece: So—all of the—all of the historical accounts that we have include Paiute involvement. The number of Paiutes involved differs from maybe 50 to like 300.

There is a strain of Paiute oral history that says that they were not involved, which is not surprising to me. Because if—if you grew up in Utah and read a Utah textbook, it’s—it’s blamed it on the Paiutes for—documents blamed it on the Paiutes for 150 years. And so I—I understand that.

But the contemporary sources—none of them can testify no presence.

Scott: Okay. So there’s no effort to specifically prosecute the Paiutes?

Janiece: There’s one subpoena that is issued, but they never seem to follow up on it.

Scott: Okay. So, any comment about the non-Mormon Mountain Meadows monument in Harrison, Arkansas?

Janiece: No.

Scott: Okay. Who was overall responsible for the decision to enact the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

Janiece: Well, these are questions. I know—these are hard.

Scott: Yes.

Janiece: There are always many questions about the massacre. The massacre would not have happened without Isaac Haight. I won’t go any further than that. I’ve already mentioned it a little bit, but he—every time it went before a council, the council shot it down and said, “No, we’re not doing this.”

But Isaac circumvented the council on two different occasions. And without that circumvention of the councils, the massacre would not have happened.

Scott: Okay. And the last question we have here is—not to excuse the massacre, but to address motive. Why was this particular group of travelers targeted?

Janiece: It’s a perfect, perfect storm. It’s a perfect storm. I have a hard time—is anyone perfect with—but you have the timing. You have the tension that they know that the federal army is marching there in southern Utah. You have some very caustic personalities. You have a lack of information.

And you have all of these things coming together in the most horrific way possible.

Scott: Oh, yeah. It’s interesting. You know, it’s one—I have critics say, “You know, FAIR is here just to put the best light on everything.” And yet we talk about things like the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which—there really isn’t a good light to turn out.

Janiece: No.

Scott: It’s just—there’s no good light.

Janiece: Yeah.

Scott: So, her book is for sale in our bookstore. I’m sure she’d be happy to sign a copy for you.

And thank you very much.

Janiece: Thanks.

Endnotes & Summary

coming soon…

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 3, 2023

- Duration: 45:05 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2023 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Mountain Meadows Massacre, Brigham Young, John D. Lee, anti-Mormon rhetoric, 19th-century media, polygamy, historical accuracy, sensationalism, Reed Smoot hearings, apologetics, Mormon identity, political cartoons, gender roles, frontier history, religious persecution, Under the Banner of Heaven, Mormonism Unveiled

Common Concerns Addressed

Was Brigham Young responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

No contemporary evidence supports the claim that Brigham Young ordered the massacre. While anti-Mormon narratives attempted to link him to the event, historical records show that the massacre was planned and executed at the local level by leaders in Cedar City, particularly Isaac Haight. The timeline also makes it unlikely that Young could have sent orders in time to influence the attack.

How did 19th-century media shape perceptions of the massacre?

Newspapers like Harper’s Weekly and political cartoons played a major role in framing the Mountain Meadows Massacre as proof of Mormon barbarism. The press sensationalized the massacre, tying it to broader fears about polygamy and theocratic rule, reinforcing the idea that Latter-day Saints were a dangerous, un-American sect.

Did Mormons disguise themselves as Native Americans during the attack?

Historical accounts confirm that Paiutes participated in the massacre, though their level of involvement is debated. However, later narratives, particularly anti-Mormon retellings, falsely claimed that white Mormons disguised themselves as Native Americans to shift blame. Dr. Johnson explains that these claims contradict both contemporary sources and the original plan by John D. Lee and Isaac Haight, which was to blame the massacre entirely on the Paiutes.

How were Latter-day Saints depicted in political cartoons and literature?

Latter-day Saints were often caricatured as dangerous, immoral, and deceitful in political cartoons and literature. Polygamy, despotism, and violence were common themes, with imagery showing Mormons luring innocent women into polygamous slavery or committing massacres in service to Brigham Young. These exaggerated portrayals fueled public hostility and justified legal actions against the Church.

What role did sensationalized narratives play in American perceptions of Mormonism?

Dr. Johnson highlights how fiction and biased reporting exaggerated the Mountain Meadows Massacre, making it a symbol of Mormon treachery. Figures like William Bishop heavily edited John D. Lee’s confessions to sell books, while novelists and journalists used the massacre as a tool to demonize Latter-day Saints. Over time, these fabricated or exaggerated stories became accepted as fact.

How has the narrative around the Mountain Meadows Massacre evolved over time?

Before John D. Lee’s first trial (1875), Brigham Young was rarely blamed for the massacre. However, by the time Young died in 1877, many newspapers had accepted the false claim that he ordered it. Over the decades, fictionalized retellings, Wild West shows, and anti-Mormon literature cemented this misconception. Even today, modern portrayals like Under the Banner of Heaven continue to repeat discredited accusations.

Were Mormon men depicted as dangerous?

Yes. Mormon men were framed as a threat to American values, particularly due to polygamy and accusations of theocratic rule. Political cartoons depicted them as predators, manipulating women and defying civilization. Mountain Meadows reinforced this image, portraying Mormon men as capable of mass murder, deception, and brutality. Dr. Johnson also notes that some narratives claimed Mormon men forced women into leadership roles, suggesting that Mormon men were both weak and tyrannical—a contradiction that highlights the bias of these depictions.

Why Do Anti-Mormon Narratives Persist Despite Historical Evidence?

Anti-Mormon narratives persist due to their deep roots in 19th-century media, political conflicts, and religious opposition. Sensationalized stories about Mountain Meadows, polygamy, and Mormon theocracy were widely circulated in newspapers, novels, and courtrooms. These narratives became entrenched in public memory, often repeated without scrutiny.

Even when historical evidence debunks false claims, modern media and pop culture—such as Under the Banner of Heaven—continue to recycle outdated accusations. The endurance of these narratives reflects broader societal biases, where the Latter-day Saints remain an “outsider” group in some circles, making myths about their past more difficult to correct.

How Did Polygamy and Sensationalized Storytelling Contribute to Anti-Mormon Rhetoric?

Polygamy was one of the most powerful tools used to vilify Latter-day Saints. In the 19th century, it was framed as both a moral and political threat—a practice that allegedly enslaved women, undermined American values, and fostered violent fanaticism.

The Mountain Meadows Massacre was often linked to polygamy, with critics claiming that a theocratic, polygamous society encouraged absolute obedience to leaders, even to the point of murder. Political cartoons and literature further exaggerated these fears, depicting Mormon men as deceitful patriarchs and Mormon women as helpless captives.

Additionally, novels, newspaper exposés, and court cases amplified these accusations, fueling a lucrative industry of anti-Mormon storytelling. This blend of moral panic, religious rivalry, and sensationalized journalism ensured that these narratives endured long after polygamy was officially ended by the Church.

Apologetic Focus

Dr. Janiece Johnson’s talk provides a historically grounded apologetic response to persistent misconceptions about the Mountain Meadows Massacre and its role in shaping anti-Mormon rhetoric. By examining primary sources, legal proceedings, and 19th-century media representations, she demonstrates how false accusations and sensationalized storytelling have distorted public perception of both the massacre and Latter-day Saints as a whole. This talk challenges the long-standing claim that Brigham Young orchestrated the massacre, the idea that Mormon men disguised themselves as Native Americans, and the portrayal of Mormons as inherently violent or deceitful. Additionally, Dr. Johnson exposes how polygamy and accusations of theocratic control fueled broader anti-Mormon narratives. Her research highlights the importance of historical accuracy in countering falsehoods and understanding the complexities of 19th-century Mormon history.

1. Historical Accuracy

Criticism: Brigham Young ordered the Mountain Meadows Massacre as part of a religious conspiracy.

Response: Dr. Johnson presents primary historical sources and legal records to demonstrate that there is no contemporary evidence linking Brigham Young to the massacre. The claim that Young issued an order to attack the emigrant party was largely a fabrication of anti-Mormon rhetoric, which emerged after John D. Lee’s trial. Furthermore, historical records show that the massacre was already underway before any possible orders from Salt Lake City could have arrived, debunking the idea of a centrally orchestrated attack.2. Anti-Mormon Rhetoric

Criticism: The Mountain Meadows Massacre proves that Mormons were violent, un-American fanatics.

Response: The massacre was a horrific but isolated event, not an example of Mormon doctrine or culture encouraging violence. However, anti-Mormon narratives seized upon the tragedy to portray Latter-day Saints as a dangerous, secretive group. Political cartoons, fiction, and newspaper editorials exaggerated and distorted the event, using it as a propaganda tool to justify government intervention against the Church.3. Sensationalism & Bias

Criticism: Mormons disguised themselves as Native Americans to commit the massacre and shift the blame.

Response: While Paiutes did participate in the attack, the accusation that white Mormons disguised themselves as Native Americans is a later fabrication. Dr. Johnson explains that John D. Lee and Isaac Haight’s original plan was to blame the massacre entirely on the Paiutes, but there is no credible historical evidence that Mormons disguised themselves. This narrative was introduced in later anti-Mormon accounts to further vilify Latter-day Saints and cast them as deceitful and barbaric.4. Mormon Identity & Theocracy Accusations

Criticism: Mormons were trying to create a theocratic government that encouraged violence and lawlessness.

Response: Latter-day Saints were frequently accused of being outside the bounds of American civilization, largely due to their distinct religious and social structures. The Mountain Meadows Massacre was used as proof that Mormons could not govern themselves and needed federal intervention. Dr. Johnson highlights how these claims were driven by anti-Mormon bias rather than factual evidence, and how similar anti-Catholic narratives were used against other religious minorities at the time.5. Polygamy & Gendered Critiques

Criticism: Mormon men were dangerous patriarchs who mistreated women and encouraged fanaticism.

Response: Anti-Mormon rhetoric often depicted Mormon men as either cruel oppressors or weak followers of a theocratic leader. Dr. Johnson notes that polygamy was a major factor in this portrayal, with political cartoons depicting Mormon men as predators luring women into polygamous slavery. Additionally, some narratives claimed that Mormon men failed to protect women and children, as seen in accounts that emphasized the massacre’s female victims. Dr. Johnson challenges these portrayals by showing how they were exaggerated to serve political agendas rather than accurately reflect Latter-day Saint men or their society.

Explore Further

- Historical summary of the Mountain Meadows Massacre

- Perpetrators of the Mountain Meadows Massacre

- Brigham Young and the Mountain Meadows Massacre

- Others involved in the Mountain Meadows Massacre

- Blood of the Prophets [1]: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

- Blood of the Prophets [2]: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

- Blood of the Prophets [3]: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Share this article