August 2022

Introduction

Let’s picture this: Your dear friend Samantha confides in you that she is removing her name from the records of the Church. “Why?” you ask, bewildered. She replies that she’s read this compelling and persuasive booklet called… A Letter to a CES Director. You sigh. You want to ask, “Really? That’s all it took?” This is because you’ve read the book too and literally nothing in it seemed all that persuasive to you.

You tell Samantha, “Hey, I’ve read that book — have you read the sequel? Or the third book in the trilogy?” And so you direct her to a Faithful Reply to the CES Letter by Jim Bennett, and then Bamboozled by the CES Letter by Michael Ash. So she goes and dutifully reads them, and reports to you that their rebuttals were unconvincing attempts to respond to the grave accusations leveled by Runnells.

And after all of this, you are left a bit confused. Why is something that seems so transparently unpersuasive to you so convincing to her? And conversely, why does something that seems so convincing to you seem so unpersuasive to her? You know for a fact that neither of you are less intelligent than the other, though in your dark moments of sadness you might start to question that. But no, similarly intelligent people can disagree in precisely this way, and do so all the time. In this presentation, I aim to one of many reasons why.

But your troubles aren’t over. You decide to chat with your mutual friend Brian. You express sadness that Samantha is leaving the Church. Your friend Brian surprises you by asking, “Why be so judgmental?”

“What do you mean?” you ask.

Brian replies, “I think our community is far too judgy of those who have doubts.” You ask what about your conversation was judgmental — you simply expressed sadness that a mutual friend, who you both love, is considering departing from her covenants. Brian replies, “See, that’s the thing. Any time people decide to live differently, we all judge them. We need to create space for people to decide to do things differently. It’s our job to just love. I don’t blame anyone for not feeling like they belong in our community, given how constantly judgmental Church members can be.”

Again, you are baffled. Before now, you didn’t see Brian as part of the “judge-me-not” crowd, but you also did not see anything in your own speech or conduct that was overly-judgmental. Is it unloving to be sad when someone is making what you think is a grave mistake? And you are now sad and confused, because you are now being told it is wrong to even be sad. What in the world is going on here? Why does something that seems like loving concern to you look like unrighteous judgment to someone else?

Raise your hand, if you are willing, if you have had experiences like either of these. It turns out that the second scenario here often has the exact same root as the first. And again, in this presentation, I hope to shine some light underneath these bewildering conversations. Ultimately, much of what is happening here is actually nonrational. What’s happening is beneath the surface, at the level of our intuitions. Based on his experiences studying hundreds of deconversion narratives among evangelical Christians, John Marriott shares this insight:

[S]o often, deconversion stories credit the loss of faith to intellectual factors alone. When that happens, the natural impulse is to take that claim at face value and address the intellectual issues head-on. While this can be helpful, it often doesn’t get to the heart of the problem. … There are a number of nonrational factors operating “off our radar,” as it were … These factors operating under the hood of our conscious awareness can serve as the source of the surface-level objections and doubts. Responding to the surface-level objections is important, but addressing their source is essential to dealing with the doubts that lead to deconversion.

(1) We all have moral intuitions that we absorb from the communities we integrate with.

My first thesis today is that we all have moral intuitions, and that we absorb these moral intuitions from the communities we integrate with. If you want, you can use the term “moral taste buds” instead of moral intuitions, and it works just as well. I draw my understanding here in part from the work of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and others. I could include an entire bibliography on this, but today, it is sufficient to say that Haidt and others have argued that we have deep-seated, gut-level reactions to people, actions, events, values, or institutions. To demonstrate, for the next couple of moments, I am going to ask you to consult your feelings — your gut-level, pre-rational reactions.

When you see this picture [Picture of Fred Rogers], how do you feel? What’s your gut reaction? do you feel warmly towards this person, or coldly? Trustful or distrustful? These are your gut-level, intuitive responses. When you see this picture [Picture of Dolores Umbridge, villainous and despised teacher in Harry Potter Franchise], once again, pay attention to your gut. How do you feel? Warm or cold? Trustful or distrustful?

How we feel towards people and institutions matters a lot in terms of what we believe about them and the sorts of judgments we make towards them. In the first instance, negative rumors about Fred Rogers will likely be taken with a huge dose of skepticism, and a much higher threshold of evidence. In the second case, negative rumors about Dolores Umbridge will be taken with a huge dose of credulity, and a much lower threshold of evidence. Jonathan Haidt argues that we have similar gut-level reactions to moral situations.

To demonstrate this, Haidt created scenarios in which people break strong social and cultural taboos — things about which our intuitions speak loudly. Here’s an example that Haidt used in his research:

A woman is cleaning out her closet. and she finds her old American flag. She doesn’t want the flag anymore, so she cuts it up into pieces and uses the rags to clean her bathroom.

By show of hands, if you are willing, how many of you have an immediate negative reaction to this? For many of us, the situation simply tastes wrong, like biting into something bitter. Here’s another example, and I apologize in advance:

A family’s dog was killed by a car in front of their house. They had heard that dog meat was delicious, so they cut up the dog’s body and cooked it and ate it for dinner. Nobody saw them do this.

Again, by show of hands, if you are willing, how many of you have an immediate negative reaction to this? Most of Haidt’s participants in the United States experienced a visceral disgust at the family’s actions. He would prod them to explain their reasoning, and then systematically dismantle their arguments.

Rather than change their mind, when backed into a corner and deprived of all their rational arguments, participants often experienced what Haidt calls moral dumbfounding. This is when we have strong moral intuitions but cannot generate further moral reasoning to justify them. And rarely did his research participants walk back or revise their moral judgments in the face of moral dumbfounding. It would be like trying to convince someone that blended pizza makes a fantastic smoothie. No matter how persuasive you are, you will rarely change their intuitions about it using reason and rationality. And in the same way, we form intuitions about a broad array of moral situations that are durable in the face of counter-argument. Let me offer one more scenario, this time, one of my own.

An adult man and an adult woman, both single, go on several dates. After the fifth date, they decide to make love. They used birth control and the encounter was consensual.

Again, by show of hands, how many of you had a visceral, negative reaction to this? That was as intense as the first two slides? Now, again, if you are willing, raise your hand if your intuitive, gut-level reaction was softer for this scenario than the first two. This is not a gotcha moment. When I showed these slides to my neighbor earlier this week, he had a negative reaction to the first two scenarios, and then literally shrugged his shoulders at the third and said, “That’s just what people do these days.” But then he paused, and said that up here [head], he knows that the third is a more weighty sin than the first two — but he doesn’t feel it quite so much in here [heart]. His moral taste buds don’t react the same.

On this, my neighbor is totally normal. The purpose of this is to show that (1) we have moral intuitions, and (2) they are stronger or weaker in response to various situations, and (3) that this doesn’t necessarily follow the relative severity of our confessional beliefs, that is, what we believe up here. It’s possible for our gut-level, intuitive reactions to diverge our cognitive judgments.

So where do our moral intuitions come from? There is no single answer. But I’ll suggest a number of possibilities:

Our family upbringing. We absorb many of our intuitions from our parents and siblings. This isn’t always direct instruction, but often modeling, sharing our reactions, and so on.

Our peer group. At some point, your peers start to influence your moral intuitions even more than your parents, particularly in adolescence. We absorb the intuitions of our peers not because they rationally persuade us, but through a process of acculturation.

Our Church community. Those we minister to and with, worship with on Sundays, spend time with during the week, can have a huge influence on our intuitions about what is right and what is wrong — and so can those who our religious communities treat as moral authorities.

Our political tribe. Most people find their moral intuitions dovetail on most issues with their preferred political tribe, again as a matter of acculturation. This one is huge. Even if we manage to cognitively disagree with our political tribe in various key respects, how we feel about situations can often still get tugged along.

Our culture. Moral intuitions vary from culture to culture. If you lived in ancient Greece, it might not even register on your moral intuitions to hear of grown men engaging in sexual behavior with adolescent boys. We tend, rightly, to look with horror on some of these practices today — our intuitions speak loudly on these issues. We tend to breathe that broader cultural air no matter what tribe or community we affiliate with.

Our entertainment. Our entertainment can be a subtle source of moral education, an extra concentrated dose of that cultural air, so to speak. Spend hundreds of hours with characters we love who act and talk in certain ways, and we can find our intuitions shifting, without any rational argument along the way. Stories educate our intuitions. Stories communicate to hearers who should be seen as protagonists, who should be seen as villains, and what constitutes a happy ending or a sad ending — and in the process, they communicate to us what to love, what to hate, what is good, and what is bad.

Notice that all but one of these represent various communities. Our family, our peers, our Church, our political tribe, our culture all represent groups of people we affiliate with. The only exception is entertainment, but I’m willing to bet the effects of TV shows on our moral intuitions are amplified when we integrate into communities of fans. Put differently, communities come to share intuitions, and the communities we identify most closely with have the largest influence on our intuitions.

A number of years ago, as a matter of morbid curiosity, I started spending unfortunate amounts of time perusing the discussion forums from former members of the Church. I had nothing in common with these folks. I was persuaded by none of their arguments, and sympathetic to none of their grievances. I was simply an online apologist who wanted to keep ear to the ground and thumb on the pulse of the conversation and the controversies of the hour.

After a while, I would sit in fast and testimony meeting, and with each awkward testimony, I would be able to write the script for how participants in these forums would find the testimony problematic. A far more interesting thing was that vicarious sense of embarrassment I began to feel as I listened to those “problematic” testimonies or Sunday school comments. Whereas before, those awkward and errant Sunday School comments might warrant an invisible eyeroll but also a warm feeling towards the loveable former high priest who is often wrong but doing his best, now I was experiencing instead that inner cringe as I anticipated the mockery such comments would bring were these forums to ever hear them and an irritation with, say, Brother Johnson for even making them: “Golly, why does he have to be one of those sorts of people?” My intuitions were changing. The moment I realized this was happening, I dropped that habit like a rock.

My point here is that we absorb the intuitions of our various communities, often without our deliberate participation. Sometimes just swimming in water is sufficient to get wet. Whodathunk? This isn’t to say that we don’t participate or cooperate at all in the formation of our intuitions, just that we can sleepwalk into them without conscious reflection of what we are doing or why. The question I often ask as I see others walk down the road towards deconversion: what new communities have they become a part of, or what new social media network or friends group have they inserted themselves into, long before this deconversion process ever became visible?

This is a trick question, because we are all part of a new community now, a brave new world of Western society and culture that is fundamentally different from the civic community we were a part of even a mere decade ago. These days, we don’t have to join an online discussion forum at all to experience the same effect that I did. We are all effectively part of a new community with new shared intuitions.

Maybe you live in a community or social circle that is quite insulated from these cultural innovations. But if your entertainment comes primarily from those who view our faith traditions with contempt, we will be influenced nonetheless. Our entertainment does not have to aggressively propagandize these cultural innovations to have this effect. In fact, it would be less effective if it did. Instead, our entertainment magistrates just need to make what our traditions treat as wrong seem normal, commonplace, and good. They just need to show us actors and characters we love doing things we once found to be unsettling or wrong, and how we feel about those things can change.

Advertisers know that the most effective persuasion doesn’t even involve words. Social psychologists speak of two kinds of persuasion: the central route to persuasion, and the peripheral route to persuasion:

The central route to persuasion involves making rational arguments. It involves directly making a case. A lawyer laying out evidence in a court case is a great example of the central route to persuasion.

The peripheral route to persuasion involves addressing our intuitions. Advertisers know that the most effective persuasion doesn’t even involve words. It just requires you to show Matthew McConaughey walking handsomely while wearing your cologne, or smiling confidently as he drives your car. These sorts of things speak to your intuitions.

Despite its now outdated branding, the “I’m a Mormon” campaign and the “Meet the Mormons” film were a perfect example of attempting to speak to our intuitions. They didn’t make a rational case for the Restoration. They just made Latter-day Saints seem both normal and extraordinary at the same time. They were an attempt to change the gut reaction people have when they encounter Latter-day Saint missionaries — so that people would start to feel warm instead of uncomfortable when they see young men with white shirts and ties walking up the street. And that’s brilliant.

I don’t want anyone to misunderstand me here — I’m not saying that rational argument isn’t important. Not in the slightest. Austin Farrer once noted, “Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish.” Without equipping those we love with rational arguments in favor of our convictions, they may find themselves dumbfounded, as Haidt would say, in the face of educated criticism. While this dumbfounding does not, by itself, demolish our intuitions, it can leave people even more vulnerable to peripheral routes of persuasion.

Anyways, I digress. At one point in our collective history, extra-marital sex was a community scandal. Now, even for many within our faith (and I count myself among them), it often barely registers at all when we see it in our entertainment. In fact, the screenwriter’s job, if they are doing it well, is to make us want them to do it, and to cheer them on when they do. It’s hard to imagine that this doesn’t have an effect on how loudly our moral intuitions speak when we encounter these things. So once again, we all have moral intuitions, or moral taste buds. Those intuitions can shift in ways that diverge from our stated convictions.

2. Our moral intuitions influence what arguments we find most persuasive.

My second thesis today is that our moral intuitions affect the weight we give to evidence and argument. First, consult your gut-level, intuitive reaction to this picture. [Picture of U.S. Congress] Many of us look upon this picture with some measure of distrust. It may be because I’m Republican and it is currently controlled by Democrats. It may be because I’m Democrat and it is currently controlled by Republicans. It may be because I’m Libertarian and it is currently controlled by… anyone at all. Let’s go with that one for now.

We often assume that our intuitions — these gut-level reactions — flow out of our moral judgments and moral reasoning. We might assume I was exposed to libertarian arguments, and from those arguments, formed libertarian intuitions. In other words, we might assume that I distrust the state because of whatever arguments I’ve been exposed for libertarian thought.

Similarly, many assume they support legalized elective abortion because somewhere in their forgotten past they encountered a compelling argument in favor of it. Others assume they oppose legalized elective abortion because somewhere in their forgotten past they encountered a compelling argument against it. And both groups assume that they haven’t yet changed their minds because they’ve never yet encountered a compelling argument for the other point of view, presumably — in each of their views — because there aren’t any. In other words, again, we assume that moral judgment follows moral reasoning.

Jonathan Haidt argues that this puts the cart before the horse. He argues that we form pre-rational moral intuitions first, and moral reasoning doesn’t come into play until we are asked to defend our moral judgments. Jonathan Haidt refers to this as the intuitionist dog that wags its rationalist tail. The rational part of us, the part of us that constructs rational arguments, is not actually king — it is the servant. In other words, my distrust of the state comes first — maybe I absorbed it from my family, from my friends group, from my social media circles, or so on. And it’s because of those intuitions that arguments for libertarianism “show up” as persuasive to me. And those exact same arguments might fall flat to someone whose intuitions are trusting towards the state and its agents.

Haidt refers to this as the intuitionist dog that wags its rationalist tail. The rational part of us, the part of us that constructs rational arguments, is not actually king — it is the servant. If you will indulge me for a moment, few of us have ever had to articulate a strong argument for why we shouldn’t, say, poop in the restaurant dining room. Everybody in this room just felt an instant, collective disgust at the very notion, and some of you might even be irritated I brought it up. When we share intuitions like this, rational argument isn’t even necessary. I don’t have to make an argument to convince you.

In other words, we only hire a lawyer when we need to make a case to a judge or a jury, or perhaps even to ourselves. So when we have shared intuitions, our rational arguments for those intuitions might be weak or non-existent. And it is only when those intuitions get challenged that we are forced to even put argument to words to support our intuitions. Our moral reasoning is the lawyer, and our moral intuitions are the client.

Haidt concluded that when it comes to changing hearts and minds on an issue — any issue — it’s far more important to speak to the client, rather than the lawyer. Imagine if you could get opposing counsel to change their mind on a case, and to suddenly side with you, against their client? That would be interesting. But it doesn’t happen, because the opposing counsel is merely being paid by the hour. You can be as persuasive as you want, and they’ll just start getting creative. We’ve all been there, where we find ourselves playing whack-a-mole with people’s concerns about the Church. It’s the client you need to reach. That is because rational argument and moral reasoning is downstream from the source of our deepest convictions.

When we encounter friends and family like Samantha, it’s tempting to try to generate new reasoning, new persuasive arguments to convince those we love to stick with what they once knew to be true. But that is often futile. This is because their deconversion is usually not the product of rational argument to begin with. What’s missing in many of these discussions is an exploration of why their intuitions changed. We can be confident a change has probably occurred, and that change probably predates their encounters with whatever arguments they believe changed their mind. Jonathan Haidt tells a story:

When my son, Max, was three years old, I discovered that he’s allergic to must. When I would tell him that he must get dressed so that we can go to school (and he loved to go to school), he’d scowl and whine. The word must is a little verbal handcuff that triggered in him the desire to squirm free.

The word can is so much nicer: “Can you get dressed, so that we can go to school?” To be certain that these two words were really night and day, I tried a little experiment. After dinner one night, I said “Max, you must eat ice cream now.”

“But I don’t want to!”

Four seconds later: “Max, you can have ice cream if you want.”

“I want some!”

Haidt uses this amusing anecdote as a backdrop for describing how our intuitions change the questions that we ask in the face of challenges to our convictions. If our intuitions lean in favor of something, our moral reasoning asks, “Can I believe this?” It looks for reasons to believe. Even the flimsiest justifications for belief will do. If our intuitions lean against something, our moral reasoning asks, “Must I believe this?” It looks for reasons not to believe — for escape hatches. Even the smallest justification for disbelief will do. It is important to note that we all do this on most issues. Arguments in favor of our intuitions are given light scrutiny, and arguments against them are given strict scrutiny.

It is important to note that we all do this. Arguments in favor of our intuitions are given light scrutiny, and arguments against them are given strict scrutiny. It’s not uncommon to see people give the strictest scrutiny to anything that comes from the conventional medical establishment — that is, they ask, “Must I believe?” and look for any possible escape hatch. But when they encounter alternative medical interventions, they give the lightest scrutiny — that is, they ask, “Can I believe?” And so it is that the tiniest flaws in medical research are nits, while even the sketchiest interventions on the alternative side are given a total pass.

And in the same way, if your intuitions tell you that the Church is fundamentally good, and its members sincere people who are trying, and that the Book of Mormon is of divine origin, then the question you are likely asking when examining the rational arguments is, “Can I believe?” And of course, in the pile of resources offered by the Church, FAIR, Book of Mormon Central, and other organizations and researchers, you’ll find plenty of permission for belief. The arguments made by apologists will probably seem quite persuasive — and even where they don’t, you’ll see them as good people trying their best.

But if your intuitions have begun to lean the other way — if your gut reaction to the teachings of President Russell M. Nelson is cringe, and if reading the Book of Mormon makes you feel like a dupe, and you have started to feel vicarious embarrassment for your friends who are passionate about the Church, then the question you are likely asking is, “Must I believe?” And in the materials offered by critics of the Church, you’ll find plenty of escape hatches. The CES letter will seem quite persuasive to you. The arguments of apologists might seem desperate, and they themselves might seem dishonest and even malicious at times.

And so if Samantha’s intuitions have changed, we can poke holes in every single argument that Samantha brings forward for why she should leave the faith, and instead of changing her mind — as we might predict if our moral judgments were a product of rational argument — she will simply experience moral dumbfounding. If she has come to feel the same way looking at this [Church headquarters] as she does when she looks at this [Barad-dûr, Sauron’s tower in Lord of the Rings], whatever counterarguments you offer are just going to seem flimsy to her, no matter how robust they might seem to the rest of us.

The fact that you are making such counterarguments might even mean that she will come to feel – at a gut-level, on the level of intuitions — the same way about you as all of us do about Sauron’s emissaries. The arguments she puts forward are a distraction. The intuitions are what needs to be addressed. I’ve recently had a number of conversations where I realized the real issue is that the other person views with suspicion, distrust, and even contempt the very same people I see as role models and moral authorities. At that point, no rational argument was going to resolve their concerns.

And for the record, I’m not saying this is true only of those who leave our faith. This is true for the lion’s share of mind-changing and heart-changing, in any direction on any issue. This is equally true of those who join the Church. This is precisely why, in fact, missionaries aren’t generally trained to persuade potential members through logical argument. Instead, they invite members to read our sacred texts, participate in our community, and to pray. This is, you might say, what prayer is all about: asking God to speak to us on the level of our intuitions.

And this is why maintaining a sense of community with those who are grappling through these cultural pressures is crucial. We are fighting a war of competing intuitions, and posturing as their ideological adversaries the moment they express doubts about the faith is certain to lose us that war — and so will pushing them into the arms of our adversaries. So sometimes the very best and only thing we can do for the Samanthas in our lives is to be an anchor and a steady presence in their life. To be the sort of person who demonstrates in word and deed that their intuitions are miscalibrated.

And, when appropriate, we can invite them to seek personal experiences with God. Encounters with the Divine have a remarkable way of changing our intuitions. A heart that was hard can then become soft. And this explains precisely the stories of so many thousands of Latter-day Saints who, bogged down and mired in various doubts and uncertainties, have found solace in sincere prayer and communion with God. As they experience the presence of the Holy Spirit, speaking to their hearts, their intuitions change.

Having the Holy Ghost speak to your heart does not suddenly resolve all your former concerns. Many will report that they never found real closure on some of their original doubts and concerns — they never find any argument, or piece of evidence, that would have given their former self any satisfaction. But after their encounter with the Spirit, suddenly it ceases to matter as much to them. No longer are they asking, “Must I believe?” They are now asking, “Can I believe?” The arguments that would have before been inadequate are suddenly good enough for now, and they can leave the rest to God. It’s not because those arguments are now stronger than they were before. It’s because they are now looking at them with a new set of moral intuitions — a new set of moral taste buds — as a backdrop. This is part of what it means to have a new heart.

3. Our moral intuitions influence our perception of community norms.

So once again, we all have moral intuitions, moral taste buds. We absorb them from culture and community. And those moral taste buds will influence what sorts of arguments for or against our faith we find persuasive. My third thesis today is that as our moral intuitions shift, the way we see our community norms also change.

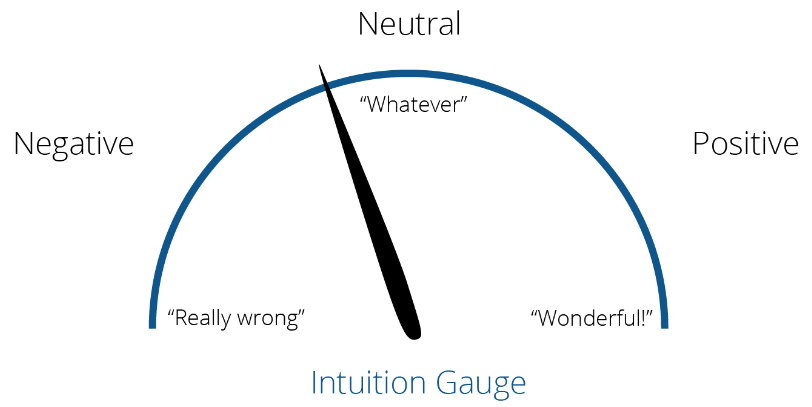

Let’s take a look at this ”moral intuition” gauge. If your moral intuitions towards a behavior shift this way – towards the negative – then you’ll start to feel warmly towards norms against that behavior, and towards those who reinforce those norms. And if your intuitions are warm towards that same behavior then any norms against those behaviors are going to feel like they are too strong for our moral taste buds. Anywhere right of “neutral” on this chart will make even the softest norms against a behavior show up as draconian and unnecessary.

To be clear, I’m not necessarily talking about our beliefs up here. I know a number of people, for example, who will tell you that they believe that extra-marital sex is a sin. But on the level of their intuitions, it doesn’t really register, or in some cases, registers warmly. Even though they believe up here that it’s wrong, they tend to bristle at any community norms against it. In fact, those norms show up to them as meddling, and as more puritanical than perhaps they really are. And they might distrust the intentions of anyone who reinforces those norms.

This is one of the central challenges of our faith, moving into the coming decades: how do we maintain strong moral convictions while also emptying out our moral intuitions? Is it even possible to do so for long? Can we really maintain a conviction that extra-marital sex is wrong, when we high-five our roommates for scoring the night before? Can we maintain for long a conviction that elective abortion is a grave sin, if we feel relief that a friend was able to obtain one? And so on for a host of other moral issues. Cognitive beliefs bereft of intuitions are fragile in the face of counter-argument and cultural suasion, and any norms that dovetail those beliefs will inevitably seem too strong.

Further, we start to see those who maintain strong moral intuitions on those matters as “judgmental”. If our friends are watching a movie, and they comment, “Eh, maybe they should wait until marriage to do that,” we immediately see them as judgy-mc-judge-face, and we come to see their gut-level reaction as judgmentalism — despite the fact that this is a totally ordinary reaction for someone who really believes, at the level of their intuitions, that extra-marital sex is wrong. In fact, anyone with stronger moral intuitions than we have, even if those intuitions are mild, can show up as unreasonably judgmental. And so when our intuitions towards behaviors our doctrines teach as sinful shift this way, we’ll start to see judgmentalism around every corner, not realizing it is our lack of reactivity towards those behaviors, not the modest moral intuitions of those around us, that is influencing that perception.

Certainly, self-righteous judgmentalism is real and often a problem — I see it all the time. It’s a symptom of pride. But not every accusation of judgmentalism is in response to self-righteous judgmentalism. Sometimes it’s just that an individual or group’s intuitions towards behaviors are stronger than someone else’s baselines. Put simply, when someone says, “You guys are so judgmental,” we should reflect and consider where to improve — but we should also realize that they might also simply be saying, “You have stronger moral taste buds than I do.” And that is now happening on a regular basis as our moral intuitions on some issues — ranging from Sabbath worship to same-sex activity — collapse in the face of social and media pressures.

Our critics often frame our disagreements as matters of love: they are simply more loving towards those who sin. But love has almost nothing to do with this chart we see here. I think we sometimes mistake our rational assent towards Church teachings for conviction, and our heart-warm in response to choices that violate our convictions for love. We sometimes come to believe that, because we don’t feel any sense of disquiet or discomfort with the idea of same-sex activity, abortion, extra-marital sex, Sabbath-breaking or a host of other sins, we are simply more loving towards those who do these things. And that those who do feel disquiet or discomfort are not loving. For example, if someone’s scruples do not allow them to congratulate their friends for their extra-marital sexual adventures, we often treat this as a lapse in love.

But this is a category error. When you really ponder this, it’s rather silly. We all know that loving others does not require us to be happy when they do things we consider to be morally transgressive. Imagine that our friends are engaging in racist speech and behavior. All of us here have intuitions all the way over here, and rightfully so. [Gauge needle all the way at “really wrong”] And if you don’t, recalibrate immediately. Yet we know, deep down, that we can still love them as Christ loves them — and feel a genuine concern for their temporal and spiritual well-being as beloved children of God — and feel a deep, visceral reaction to their racist behavior, and while reinforcing the strongest norms against that behavior.

So again, the strength and direction of our moral intuitions about any given behavior has no inherent correlation with how much we love anyone. Having strong moral intuitions does not make us more loving, and having weak moral intuitions does not make us more loving. The question is what, at the level of our intuitions, we actually see as wrong. The real issue is often that our critics — even sometimes those within the Church who claim to share our beliefs — no longer share the same, gut-level intuitions that some things really are sinful. For those issues where our critics’ intuitions do speak loudly, loving others while disagreeing with or discouraging their choices suddenly makes perfect sense. And because we don’t have a strong vocabulary for talking about our moral intuitions, we often gloss over this distinction.

The strength of our moral intuitions does dovetail with whether we want to reinforce certain norms or dismantle them. We can go either route with a heart full of contempt for those who differ or a heart full of grace and kindness towards those who differ. And I know a number of people whose moral intuitions are over here [Gauge needle at “wonderful”] on certain issues who believe they are more loving for it, and they certainly act like it, until they encounter someone whose moral intuitions towards popular trends are over here, [Gauge needle barely into negative] and suddenly all that grace disappears. Because it’s not actually about love to begin with.

And finally, one additional caveat: even though love is not inherently at issue here, it can become difficult to continue strong, collegial and familial relationships with family, friends, and neighbors if our intuitions about their sexual activities scream as loudly as our intuitions about child abuse or rape. So some recalibration may be needed as we interface with new cultural norms and interact with those who do not share our values. But even here, the strength and direction of our moral intuitions on pretty much any moral issue is unrelated to the question of how much we love others, or how much we are willing to sacrifice for them as we seek after their temporal and spiritual welfare. Love means putting others before self — it’s not merely a matter of warm feelings.

There’s errors in two directions here: we can error towards condoning the sin, or towards condemning the person. Genuine, Christlike love is neither. Instead, it is discerning. It involves being clear-eyed about both the perils of sin and the divine potential of every individual. Our goal is to ensure that our intuitions about the soul-worth of people are never mixed up with our intuitions about the choices that they make. Our goal is for sin to taste bad to us — or as Nephi pleaded with God, “Wilt thou make me that I may shake at the appearance of sin?” But our goal is also for people to show up to us as full of divine potential and worthy of our concern, service, and love.

So I am not at all saying that we should feel contempt or disgust towards people who engage in activities we believe are sinful. That violates the precepts of our faith and the invitations of prophets and apostles to treat with kindness and respect those who do not share our values. And I will say that seeing people with contempt, celebrating their misfortune, and being dismissive of their hardships, difficulties, and pain, is sure-clear sign we have drifted into spiritual dangerous territory. I will say, however, that it is well within the bounds of Christian love to feel disquiet, discomfort, and sadness when those we deeply love do things that we consider to be morally wrong. And in fact, I would suggest that if we really believe those things are moral wrongs — on a level of genuine conviction — it would be strange not to. A heart full of genuine Christlike love is in no way incompatible with having strong moral taste buds.

And my argument is that it is possible to hollow out our intuitions about sin long before we ever begin expressly condoning it — and that this undercover deconversion can have consequences down the road, in terms of the sorts of arguments (for and against our faith) we find persuasive, and the sorts of norms we find overbearing. And because our moral intuitions influence our actions and reactions more thoroughly than our cognitive beliefs, we can become bewildered as those who claim the same doctrinal beliefs as we do begin to react indistinguishably from our critics to church policies or the latest cultural developments. They may share our beliefs, but they share the intuitions of our critics.

And this may be why we all now have Brians in our lives who find even gentle community norms to be too strong for their tastes. And because others leaving the Church barely registers on their moral intuitions, they might see our sadness over it as overly-judgmental. It’s not always because they cognitively disagree on matters of doctrine. But when two individuals no longer share the same intuitions, norms — such as norms of chastity, covenant-keeping, sabbath-keeping and so on — are just going to seem different to each of them.

A change is in the air, so to speak — a change brought about in large part by a changing culture that now makes our beliefs, beliefs that might have been uncontroversial a mere two decades ago, seem backwards and embarrassing. It’s in the cultural air that we breathe, so we can hardly blame anyone for absorbing them. It’s like getting a second-hand high when all of our neighbors are smoking weed, or trying to wade through the swamp without getting wet, or trying to walk through a forest fire without breathing in smoke. It should not surprise us to see these new intuitions rub off on our friends, neighbors, peers, and even ourselves — it would be surprising if they didn’t. And in the process, as our intuitions change, it is natural for us to start seeing judgmentalism everywhere we look. My hope is that we can be clear-eyed about why this is happening.

So again, our moral intuitions influence what arguments we find most persuasive, and our perception of community norms. Let me stitch together both of these points real quick. Most of us don’t have a thermostat or barometer on our intuitions. We don’t have one of these [Moral intuition gauge], nor do we have Jonathan Haidt drilling us with scenarios and questions designed to elicit a reaction. The best and only real gauge we have for our intuitions is how norms show up to us, what sorts of commentary we start finding overly-judgmental, and what sorts of arguments start to fall flat and what sorts start to ring true and convincing. And so we might not ever realize our intuitions have changed until arguments that didn’t seem persuasive before now suddenly do — and so it would be no surprise if we walk away thinking it was those arguments that did the trick. Or perhaps we don’t realize our intuitions have changed until suddenly our Church community starts to appear more judgmental than it used to look, and so we come to think it has actually become so.

In this way, we come to believe that our disaffection was purely due to intellectual issues, rational factors — or because the Church is changing — not realizing what was happening beneath the surface all along — how we were changing. We balk at the idea that our disaffection is due to sin, as some assume, because we see no grave sin in our lives. We aren’t using pornography, or using addictive substances. All we’re doing is watching Netflix — and that certainly isn’t a sin. And nor is using TikTok. Or using other social media to connect with like-minded others and plug ourselves into a steady stream of commentary from popular social influencers. And since none of these are — by themselves — sinful, we might miss how our indiscriminate consumption of entertainment, social media, and social commentary has imprinted on our moral intuitions and fundamentally changed our moral taste buds.

And so it is that we can suddenly find ourselves in the faith but no longer of the faith, so to speak. Our confessional beliefs — that is, our stated, consciously held beliefs — are suddenly at odds with our convictional beliefs, which reside in the level of our intuitions. And those confessional beliefs — bereft of that convictional foundation — are then suddenly vulnerable to counter-argument in a way that they weren’t before. For those who experience this, it’s wildly disorienting. It’s no wonder that some describe it as a shelf breaking. They think it’s the weight of their intellectual doubts that is doing the breaking, because that is how they are experiencing it. They aren’t lying or misleading — they earnestly and honestly experience it that way. And earnest, honest experience can still mask the truth of the matter.

The more I study the social-intuitionist theory of moral judgment, the more I realize how perfectly apt the depiction is in Lehi’s dream. In this dream, individuals are not carried away from the iron rod or the tree of life by clever people making rational arguments — although the mists of darkness can certainly represent that. It is often that sense of embarrassment that comes when we heed too much the voices of those within the great and spacious building, and begin to absorb their intuitions — their moral taste buds, so to speak — the norms of our covenant community start to look and taste bitter to us.

For example, we might begin to become embarrassed by our former convictions, or by our peers within the Church who espouse. We might become ashamed of the institutional church and its policies on sexuality and gender. We might start — on the level of our intuitions — to see temples as excess and waste. We might start to see bishops as potential abusers. The Book of Mormon might start to show up as “weird.” And this process can happen over a slow process of time of gradual acculturation, beneath the level of our conscious awareness, as we begin to spend more time in that great and spacious building in our movies, TV shows, music, and discussion forums.

4. We can seek to align our moral intuitions with God’s by standing in holy places.

None of this should imply that responding to intellectual objections is pointless. As mentioned before, rational responses to frequent objections can carve out room for our loved ones to “doubt their doubts.” It can provide opportunities to pause and consider other factors that might be influencing our faith journey. But it might mean that the path towards reconversion and conviction once again requires something more than rational argument. Marriott explains:

Instead of tackling these objections head-on, we think a different approach is warranted. And that is to draw attention to the nonrational factors—most of which we’re entirely unaware of but which inform and direct our reason. These nonrational factors, not objective reason or clear thinking, can often be the true source of our doubts. But they do their work imperceptibly. They’re sneaky, operating outside our conscious awareness. But make no mistake—their influence on what we believe cannot be overstated. They’re deep and powerful as an ocean, and believers, like swimmers, can find themselves carried along by these threatening currents beneath the surface. It’s our contention that in order to navigate the surface doubts, we need to do more than just try to swim harder against the tide by seeking surface level apologetic answers.

My final thesis today is that we can take proactive measures to protect our moral intuitions, so that we are not at the mercy of the social tempest, tossed about with every wave and wind of social fad. The goal here is not to simply fossilize our intuitions as they currently are. We are all products of culture, for better or for worse, and there are certainly ways in which our intuitions and moral taste buds can and should evolve. For example, our collective intuitions about interracial marriage have changed, and that’s awesome. So the goal is absolutely not to preserve our intuitions as they now are. The goal is to align our intuitions with God’s. To learn to feel about others and their behaviors the way He feels about them.

Joseph Smith taught, “Our heavenly Father is more liberal in His views, and boundless in His mercies and blessings, than we are ready to believe or receive; and at the same time … more ready to detect in every false way, than we are apt to suppose Him to be.” Many seem to believe that loving like Christ means learning to overlook sin, to soften our intuitions about sin. But Christ himself has stated, “I the Lord cannot look upon sin with the least degree of allowance.” So Christ did not and does not overlook sin, nor does He ask us to either.

Rather than leading to self-righteous judgmentalism, truly becoming “ready to detect in every false way” makes us humble, because we recognize our fallenness and complete dependence on the merits of Christ. And that means I stop making excuses for the various ways I alienate myself from God. We must teach in word and deed that God loves everyone, no matter how far we have wandered. It is precisely because God loves us that He wants to draw us back onto the straight and narrow path that leads us to Eternal Life. Joseph Smith further taught, “The nearer we get to our heavenly Father, the more we are disposed to look with compassion on perishing souls; we feel that we want to take them upon our shoulders, and cast their sins behind our backs.”

In other words, we become most like Christ not by blinding ourselves to sin, but by seeing it more clearly. We become like our Father in Heaven not by anesthetizing our moral intuitions, but calibrating them against divine sources. So how do we properly educate or calibrate our moral intuitions? We can start by taking care that we are not miseducating or miscalibrating them.

First, we can be judicious about the time we spend consuming popular entertainment. While we should befriend and associate with those with different worldviews than our own, we do not have to be entertained by the same things they are. We can and should be selective about the media we bring into our homes. I do not believe we need to become cultural snobs. But I do believe that many of us spend far more time passively consuming worldly entertainment than we have to, and that this is a significant way in which we educate or mis-educate our moral intuitions. We can seek out entertainment that showcases virtue and goodness.

Second, we can be cautious about the time we spend consuming social media commentary. Again, I don’t think the proper amount of social media exposure is always zero. But just like my experience with online discussion forums, the constant drip-feed of popular social media commentary can have a tremendous influence on our moral intuitions. Even when we are on guard, we can still start to absorb the intuitions of those whom we spend the most time reading and listening to in our social media circles. So we can seek out commentary from people who are discerning and who have intuitions we trust — and when necessary, by just tuning out.

Third, we can surround ourselves with people who have convictions we want to emulate. Be friends with those who don’t share our values. But also find anchors in your social circles, individuals and groups of friends with strong moral intuitions. This is especially important if you know yourself to be the kind of person who “chameleons,” who easily absorbs the intuitions of those you spend the most time with. It is uncontroversial that choosing friends who bring out the best in you can have a lasting impact in your life. And when it comes to the Samanthas in our lives, we can be those people. Absolutely maintain and cultivate those relationships. Be their anchors.

Fourth, we can invest time in the word of God. A handful of sporadic and irregular forays into scripture isn’t enough to keep us anchored in our faith. When we open up our sacred books and drink from the teachings of Christ and His prophets through time, we open our intuitions to the influence of God. And this is why, I believe, the ancient Israelites were instructed: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength. These commandments that I give you today are to be on your hearts. Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up.”

We can invest in sacred ordinances. The Lord taught, “That thou mayest more fully keep thyself unspotted from the world, thou shalt go to the house of prayer and offer up thy sacraments upon my holy day.” The sacrament is, among many things, a metaphor for the way Christ nourishes our hearts and souls, and participating in this ritual on a weekly basis can provide us with spiritual fortitude. President Nelson stated, “In the coming days, it will not be possible to survive spiritually without the guiding, directing, comforting, and constant influence of the Holy Ghost.” It is significant, then, that the promise of the sacrament is the continual presence of the Holy Ghost in our lives.

And finally, we can stand in holy places. When we step out of the temple after an hour or two of service, we carry with us an added measure of spiritual power. And I believe that part of this tremendous spiritual power is the way the temple ordinances influence us on the level of our intuitions — what we consider important, what we consider unimportant, what we consider holy, what we consider profane. We might not see it on a given day, but I believe that with each visit that spiritual power — that influence on our core intuitions — accumulates like the dews from heaven.

I want to end with a quote from President Russell M. Nelson, from last fall’s general conference. He spoke of the renovations being made to the Salt Lake Temple:

We are sparing no effort to give this venerable temple, which had become increasingly vulnerable, a foundation that will withstand the forces of nature into the Millennium. In like manner, it is now time that we each implement extraordinary measures—perhaps measures we have never taken before—to strengthen our personal spiritual foundations. …

Unprecedented times call for unprecedented measures. My dear brothers and sisters, these are the latter days. If you and I are to withstand the forthcoming perils and pressures, it is imperative that we each have a firm spiritual foundation built upon the rock of our Redeemer, Jesus Christ.

We’ve been speaking today of the foundation of our moral convictions — our moral intuitions. We’ve explored the way cultural forces are often eroding or shifting our moral intuitions in ways that imperil our convictions. We’ve explored how this often happens without our conscious awareness, beneath the surface, as foundations so often are. We’ve explored how these shifting moral intuitions change how persuasive arguments for or against our faith seem to us — and how this explains Samantha’s experience at the beginning of today’s presentation. We’ve explored how these shifting moral intuitions can make modest community norms that support righteous living feel overbearing to us, and how this can explain Brian’s reactions at the beginning of today’s presentation. And we’ve explored some practices that can help us safe-guard and more deliberately calibrate our moral intuitions — to develop an educated conscience.

And I want to share my conviction that the solution — the way forward — in strengthening those foundations is precisely what President Nelson has taught. I’ve been describing these issues in the language of psychology, but psychology is not the answer. Living the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ is the answer. The answer is found by immersing ourselves in the word of God, seeking encounters with God, and by investing time in sacred places like the Holy Temple of God, and in all these things, trying to keep ourselves unspotted from the world. And through this all, our attention will always be directed towards Christ, our Savior. It is His moral intuitions about and compassionate love for every individual we are all striving to emulate.