Ryan, from Book of Mormon Central, introduced a new project called Evidence Central, aimed at making evidence related to the Restoration more accessible, understandable, and defensible. Evidence Central features articles that distill complex academic research into user-friendly summaries, categorized and presented through an interactive website interface. The goal is to help strengthen faith by providing comprehensive evidence that can support testimonies, especially for those struggling with doubts.

This talk was given at the 2021 FAIR Conference on August 4, 2021.

Ryan Dahle, a researcher at Book of Mormon Central and project manager for Evidence Central, specializes in making scholarly research accessible to a general audience through clear and engaging resources.

Transcript

Ryan Dahle

Introduction

All right, so as mentioned, my name is Ryan Dahle.

I work for Book of Mormon Central, and for the past couple of years, I’ve been helping develop a new project called Evidence Central. My presentation today is just going to introduce you to this new resource, explain why it exists, and hopefully get you as excited as we are about its current progress and future potential.

Evidence Central is a website, a YouTube channel, and a Facebook page developed by Book of Mormon Central. It’s made possible through the generous support of the Charis Legacy Foundation.

Evidence Central

Evidence Central officially launched in September of 2020 and is now part of Book of Mormon Central’s growing ecosystem of resources,

Purpose of Evidence Central

The purpose of Evidence Central, in particular, is to increase faith in Jesus Christ by making evidences of the Restoration more accessible, understandable, and defensible. So, in contrast to the other resources, it’s specifically focused on centralizing evidence-related information. Currently, we’re focused on the Book of Mormon, but eventually, we will cover other Restoration texts such as the Book of Moses and Book of Abraham.

For decades now, a diverse and growing body of evidence pertaining to these revelations has been brought to light through scholarly research. But for a general audience, most of this information is too dense, too scholarly, and too hard to find. To help remedy this problem, Evidence Central has begun the process of identifying, categorizing, summarizing, and creatively presenting the available evidence in a brand-new format.

So now, I’m going to give you just a little bit of a show and tell and walk you through our website.

How it Works

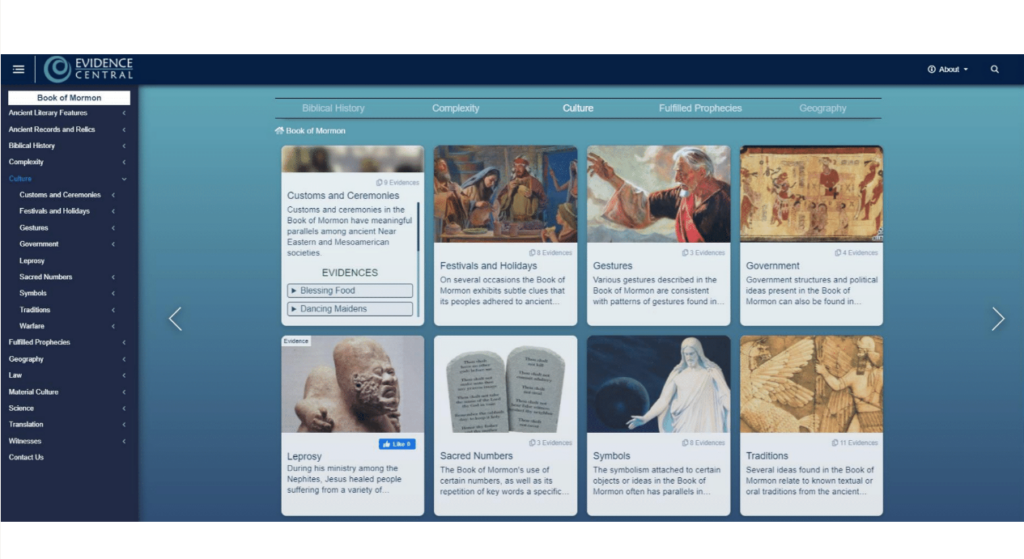

Evidence Central uses different interfaces to communicate evidence data. When you first visit the website, the default interface presents evidence types by main categories and subcategories. You’ll notice that on the left, there’s a dropdown menu.

You can close this menu, but it opens by default when you visit the website because it’s so useful for keeping track of what category and subcategory you’re looking at. You also have a slider menu at the top and arrows on the right and left as further navigation options. These menus are linked so that navigating one of them automatically makes adjustments to the other.

You’ll notice that the tiles in the center are the main feature of the interface. Some of these tiles are sub-categories of evidence, while others are individual evidences marked by the word ‘evidence’ in the upper left-hand corner. Both types of tiles are dynamic, meaning that if you hover a mouse cursor over them, the tile will expand, and you can see more of its information.

Navigation

When hovering over a category tile, you’ll be able to more fully see its abstract, which briefly explains what’s in that evidence category. Below that, you’ll see the tiles for individual evidences in that subcategory. You can then click on any of these tiles and read its abstract. So, basically, the design is meant to maximize a user’s ability to quickly survey a variety of related topics, making it possible to sample main categories, subcategories, and individual evidences at a glance.

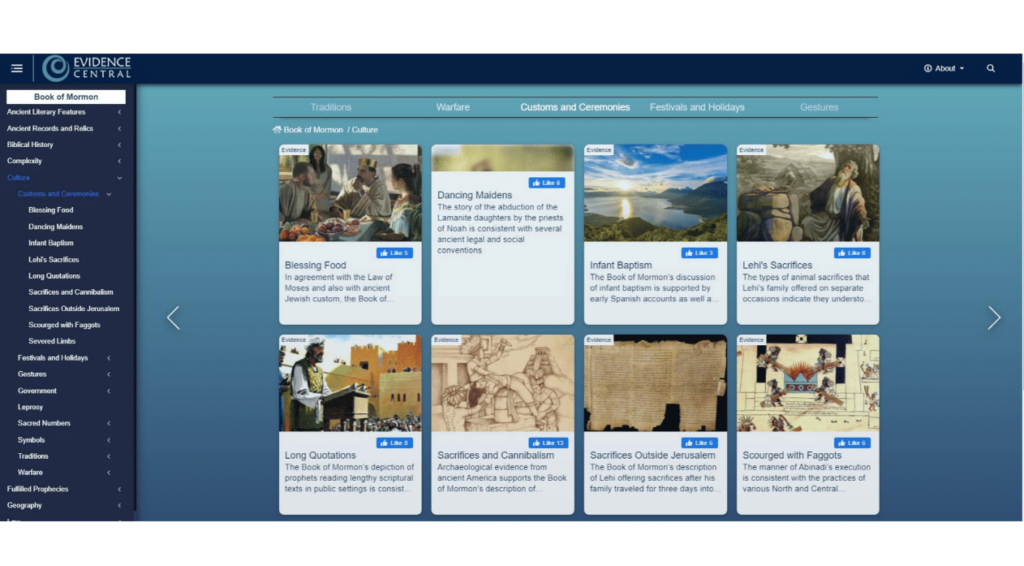

You can also click on the category tile and expand its contents so that instead of seeing just titles, each individual evidence gets a full tile of its own. For instance, if you click on the ‘Customs and Ceremonies’ category, it’ll bring you to this page which only features individual evidences. Once again, all of these tiles are dynamic, and if you ever feel lost, you can always look at the menu on the left and figure out exactly where you’re at.

In this case, it would be in the main category of culture, the subcategory of customs and ceremonies, and then you’re looking at all the individual evidences in that category. Alternatively, you can use the search bar in the upper right-hand corner if you know specifically something you want to look for; that would be very helpful.

Examples

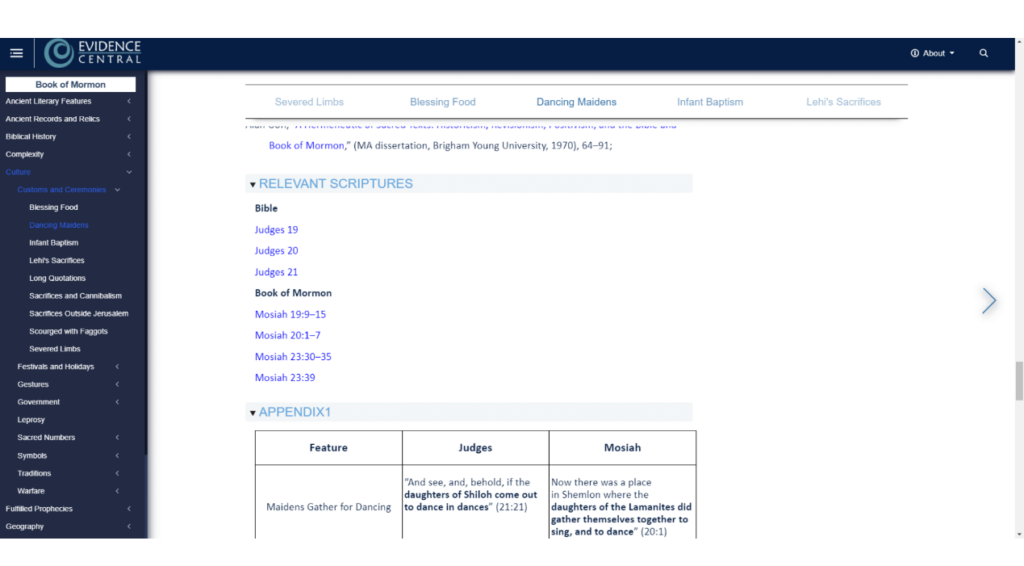

So now that you’ve seen how the interface works, let’s go into the articles themselves. Let’s say, after reading the abstract for the ‘Dancing Maidens’ evidence, you decided it’s something you want to learn more about. So, you click on it to access the article. When you get to the article’s webpage, the first thing you will notice is that the navigation options are still there, allowing you to quickly get back into the tile-based interface.

The top of each individual evidence article has a title, a section on evidence data which tells more about the evidence type and publication. It has a header image and related evidences on the right. Then an abstract which briefly explains, usually in only one or two sentences, what the evidence is about.

Below that, we have the evidence summary which attempts to explain the evidence as clearly and succinctly as possible. Each summary has been richly illustrated and is typically broken down into subsections for easier navigation. Some of these articles are very short, occasionally less than 500 words in length, while others are longer, sometimes because they summarize multiple aspects of the same evidence or because they provide original research that would be difficult to concisely explain without being able to reference a longer, more in-depth article. So, there’s some variation in the length of these articles, but even the longer examples are much shorter than the typical article in an academic journal or the typical chapter in a book.

As far as breadth of content goes, these evidence summaries derive from numerous fields of academic study, including disciplines such as archaeology, linguistics, literary studies, biblical studies, legal studies, geography, sociology, geology, ecology, and so forth—lots of ‘ologies’.

The reason this research has been made available in the first place is because scholars and researchers with a wide variety of interests and backgrounds have devoted their time and expertise to the study of restoration texts. Without the inspired and tireless efforts of a diverse group of people, this resource could never exist.

Evidence Articles

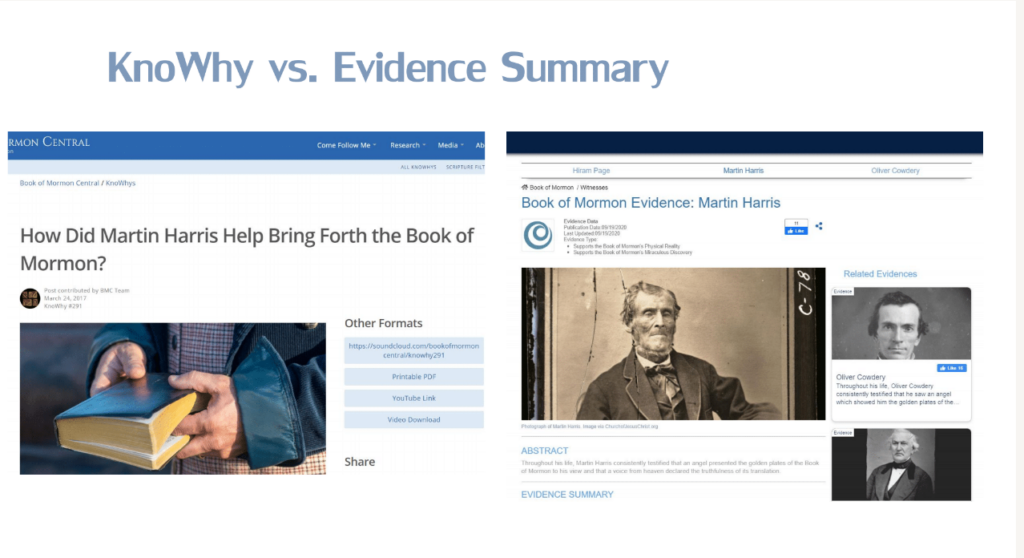

Unlike the ‘Know Whys’ published by Book of Mormon Central, our evidence articles aren’t presented as questions. They don’t have a devotional component, nor is content ever discussed simply to help a reader better understand some aspect of a restoration text. Instead, each article is strictly focused on a particular evidence.

These evidence summaries strive to maintain an academic voice throughout, avoiding emotive language, overzealous claims, and overstated discussions of the evidence. We certainly have tried to be clear about why we think something counts as evidence, but we mostly want this information to speak for itself and to let readers decide its ultimate worth and significance.

Internal Review

The claims made in our research are thoroughly sourced, and before publication, they always go through internal review by scholars and researchers at Book of Mormon Central.

This, of course, doesn’t mean they will be free of error. If you ever find something amiss, whether it be a simple typo or a more substantive error in content, please use the contact form available on the website and let us know. In some ways, these are living documents. As research moves forward, we’ll try to make updates to existing articles as our time and resources permit.

Also, we welcome ideas for new evidence, feedback on the design and functionality of our website, and any personal anecdotes about how this resource has been helpful to you or those that you know. Right now, the website is optimized for desktop, but we have plans to make it much more user-friendly for mobile. We’re currently developing new interfaces for navigating evidence and will continue to expand and refine the interfaces we already have.

Coming Soon

Soon, we’ll be publishing a new interface that, among other things, allows users to see the most recently published evidences so that you can always know what’s new on the website. We’ll also soon be publishing associated video content using vector graphics that will further expand the reach and appeal of this resource for different audiences, including youth and children.

As a sample, here’s a still image from a video about the plausibility of Laban possessing a steel sword in Jerusalem around 600 BC. This video series should make its public debut in the near future.

So now that I’ve taken you on a tour of the website and provided some updates on some of the projects in development, you may be wondering why all of this is being made available in the first place.

How Evidence Central can Serve You

Evidence Central can serve different audiences in different ways. For scholars, this resource helpfully consolidates information and relevant sources. It helps users identify relationships that might not otherwise be apparent between separate lines of evidence. It provides easier ways to navigate and access evidence-related data, and in some cases, it adds original research or significantly updates existing research.

For those who already have strong testimonies, Evidence Central can enrich and supplement the faith that you already cherish, adding new dimensions to your testimony and helping prepare you for times when your religious convictions may be tested in unexpected ways. It can also give you the tools and the information that you may need to help family members or friends who are having a crisis of faith or who might experience one in the future.

But first and foremost, this resource is intended to directly help those who are personally struggling with doubts about the restoration or whose testimonies may be wavering for whatever reason. It’s always important to remember that in the calculus of faith, spiritual evidence has priority.

Empirical Evidence

One important advantage of spiritual experiences is that they are empirical in nature, meaning that we experience them directly through our senses, typically through our emotions, our thoughts, or both. Not all types of evidence have the advantage of being so immediate and so personal.

In addition to its role in confirming important truths, the influence of the Holy Ghost brings with it peace, comfort, and joy. In other words, communication with God is much more than just shaking a magic eight ball to get answers from heaven. Experiencing God’s power and influence within us has intrinsic value. The very nature of the spiritual experience itself increases our happiness and gives added meaning and purpose to life.

Thus, divine communication helps influence not only what we know but who we become. So, in some ways, spiritual evidence is uniquely powerful, persuasive, and meaningful. Yet it also has what I consider to be divinely tailored limitations.

Just as God doesn’t want to prove spiritual realities through incontrovertible secular or physical evidence, He likewise doesn’t want to compel us to believe through overwhelming spiritual manifestations. The scriptures describe divine communication as most often taking place through the still small voice.

Limitations of Spiritual Evidence

In his famous discourse on faith, Alma acknowledged that isolated spiritual confirmations do not immediately result in fully mature and unwavering testimonies. As Alma put it,

And now, behold, after ye have tasted this light, is your knowledge perfect? Behold I say unto you, nay; neither must ye lay aside your faith, for ye have only exercised your faith to plant the seed that ye might try the experiment to know if the seed was good. But if ye neglect the tree and take no thought for its nourishment, behold it will not get any root.”

According to Alma, we have to continually strive for spiritual development with an abundance of patience, diligence, and long-suffering. In other words, gaining an unwavering testimony amounts to more than just having a few good feelings. Instead, God offers a type of spiritual experiment that only reaches its full evidentiary power as we consistently, repeatedly, and sincerely apply it in our lives. The longer and more faithfully we keep the full spectrum of commandments and authentically live the gospel of Jesus Christ, the longer we have to observe the consistencies and nuances of spiritual experiences and to learn to discern them from other types of cognitive and emotional sensations.

Using Our Minds

Which I think brings up an important point: Whether we’re talking about evidence derived from history, science, archaeology, or from the spirit, we still have to use our minds to interpret the data. Just as historical information can be interpreted in different ways, most spiritual sensations can be explained in different ways. Especially in the beginning stages of a faith journey, even spiritually mature individuals often struggle to know when subtle thoughts and feelings come from God or from some other source. It takes time and effort to grow into the principle of revelation. Some may see these limitations as sufficient grounds for rejecting the validity of spiritual experiences altogether, but I see the subtlety of most types of spiritual evidence as a divinely implemented safeguard, which helps preserve agency and ensures we’re not robbed of opportunities for spiritual growth.

The limits placed on spiritual evidence simultaneously provide room for faith and for doubt, making spiritual development a true test of character and agency. These same limits also provide a genuine need for intellectual effort, where we have to continually study things out in our minds as part of the revelatory process. The combination of reason and revelation helps produce a more fully mature, informed, and well-rounded faith.

In the same address given at a 2017 Chiasmus Jubilee Celebration co-sponsored by Book of Mormon Central, Elder Holland remarked,

Our testimonies aren’t dependent on evidence; we still need that spiritual confirmation in the heart of which we’ve spoken. But not to seek for and not to acknowledge intellectual, documentable support for our belief when it is available is to needlessly limit an otherwise incomparably strong theological position and deny us a unique persuasive vocabulary in the latter-day arena of religious investigation and sectarian debate.”

“Thus armed with so much evidence, we ought to be more assertive than we sometimes are in defending our testimony of truth.”

Evidence Central is striving to meet this call to action and to do so in a way that is not contentious or divisive. There is a genuine need to provide faithful and informative answers in response to criticisms of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Response to Criticism

FAIR and other organizations and individuals have done an admirable job in helping provide this needed response to criticism. Evidence Central, however, takes a distinctly different approach to defending faith. Rather than focusing on the flaws and limitations of critical arguments against the Church, we wanted to create a space where people can explore and comprehend the depth and breadth of the positive evidences supporting the restoration. Evidence-based knowledge can be an important supplement and, in some cases, even a crucial lifeline for those who sincerely want to retain their faith in the restoration but who may be assailed by doubts or who are struggling to have or discern spiritual experiences.

In my opinion, the secular evidence supporting Joseph Smith’s prophetic calling and the authenticity and antiquity of his revelations is remarkably strong, especially when viewed comprehensively.

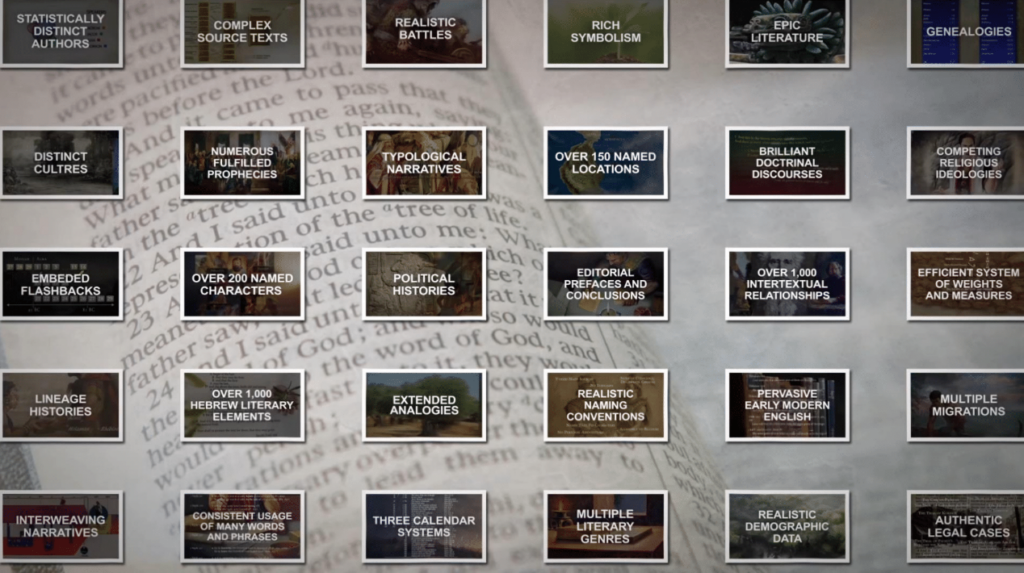

Currently, we have more than 200 individual evidence articles on Evidence Central, with literally hundreds more to go. I keep being asked if we’re running out of evidence to discuss, but as far as I can tell, we’re just getting started.

Yet the evaluation of evidence involves more than just quantity; it’s also about quality. Do these evidences hold up under scrutiny, both individually and collectively? We certainly acknowledge that some individual examples we’ve highlighted are more persuasive than others; they aren’t all home runs, but many of them are quite good, and some individual evidences are exceptionally strong. However, I believe that their true value and strength can only be assessed collectively. This is because many categories of evidence are interrelated and, in some ways, interdependent.

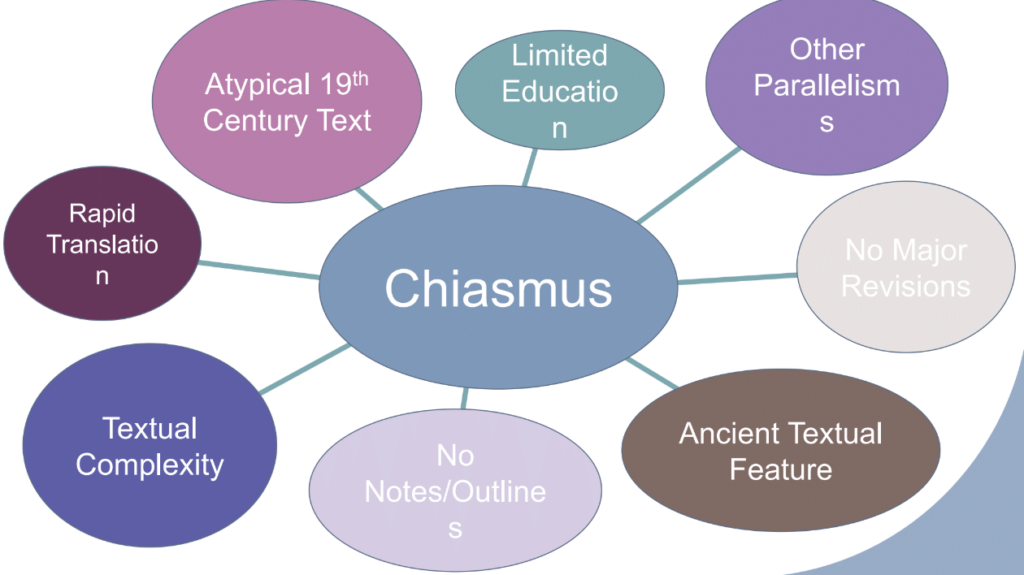

Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon

The presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon provides a good example. As many of you know, chiasmus is a literary feature that is found abundantly in ancient texts from a variety of languages and time periods. It’s particularly prevalent in Hebrew literature but can also be found in Egyptian and even ancient American texts, which are all relevant to the Book of Mormon’s claimed ancient origins.

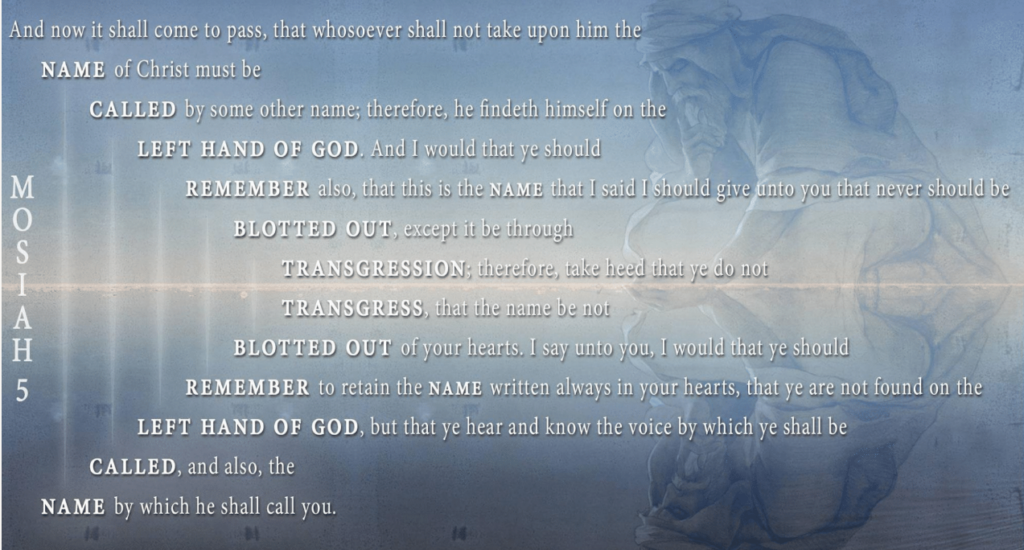

Chiasmus can be described as an inverted parallelism where a sequence of ideas is presented in one order and then given in reverse order. Hundreds of proposed chiasms have now been identified in the Book of Mormon, such as this example from the fifth chapter of Mosiah, many of which are of the complex multi-layered variety. Some of these even have solid statistical support, in addition to being persuasive by other literary measures.

It’s unlikely that Joseph Smith learned of chiasmus from reading scholarly literature in his day or by simply discerning its presence in the Bible. The vast majority of Western readers aren’t prone to recognize anything more elaborate than chiastic couplets. And even though some English authors before and during Joseph’s day were using chiasmus, it wasn’t a standard or prominent aspect of literary instruction outside of Shakespeare’s works. Most instances from Joseph Smith’s day and before that I’ve been able to identify are either macrochiasms or of the simple ABBA variety.

Chiastic Structures in the Book of Mormon

In other words, when looked at collectively, the variety, quantity, and complexity of the chiastic structures found in the Book of Mormon seem very much out of place for an English text written in the 19th century. But this is only part of the issue. Even if Joseph Smith was delving into rare chiastic research or even if he was unusually gifted at spotting the presence of chiasmus in biblical texts or even if he noticed its use by other authors, all of which are technically possible but seem quite dubious in my opinion, there was still the task of creating all of these original poetic structures and then integrating them into the translation process. And this is where related categories of evidence come in.

We don’t know precisely how many years of formal education Joseph Smith had prior to 1829, but there’s reason to believe it was quite limited. Virtually everyone—friend, foe, and neutral observer alike—who commented on his education cast him as being relatively unlearned at the time he translated the Book of Mormon. The 23-year-old Joseph was not categorically illiterate, but he certainly lacked literary expertise. He was definitely not a trained scholar.

So, assuming that he had the literary talent to create so many complex chiastic structures is questionable to begin with. But then we also have to think about the translation process. The extant portions of the Book of Mormon, the original transcript, indicates that Joseph Smith didn’t substantively revise the text before its publication. In other words, the dictation process reported by scribes and witnesses resulted in what was essentially the final draft of the text. Also of note is that a variety of source documents indicate that Joseph Smith dictated the Book of Mormon’s more than 269,000 words in approximately 60 working days.

Joseph Smith

Anyone who’s prepared the final draft of a lengthy complex document for publication will recognize this as an exceptionally rapid pace. We have a report from Emma Smith and a recorded interview from David Whitmer indicating that Joseph Smith wasn’t using any notes or manuscripts to aid his memory. Among the more than 200 historical documents relevant to the translation, we have many reports that are consistent with this claim and no reliable evidence to the contrary.

There’s one final thing that should be considered: the presence of chiasmus is hardly the only complex aspect of the Book of Mormon. First of all, the text features a variety of other parallel structures, some of which are also complex, pervasive, and turn up in ancient Hebrew literature.

Complexity in the Book of Mormon

But more importantly, the Book of Mormon is filled with names, dates, locations, intertextual relationships, embedded documents, a variety of literary genres, complex narratives, masterful sermons, distinctive doctrines, timeline disjunctions, fulfilled prophecies, editorial previews, and so forth. There is a lot more going on in the text than just chiasmus, and yet, all of this literary, geographical, chronological, editorial, doctrinal, and neurotological information is given virtually without error.

The text is remarkably complex and yet consistent on numerous fronts. I’ll provide just a few examples of how this type of internal textual consistency relates specifically to the evidence for chiasmus.

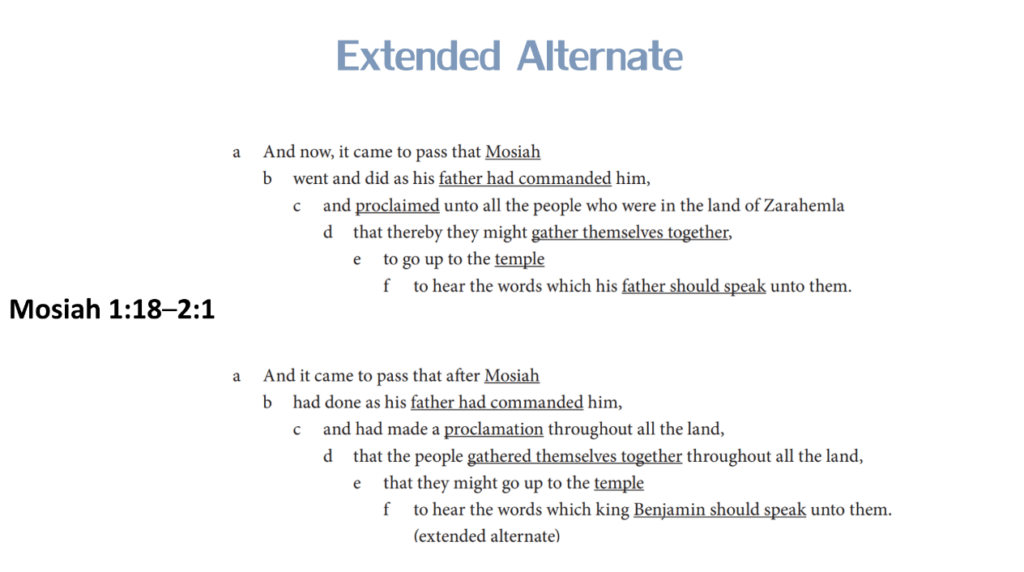

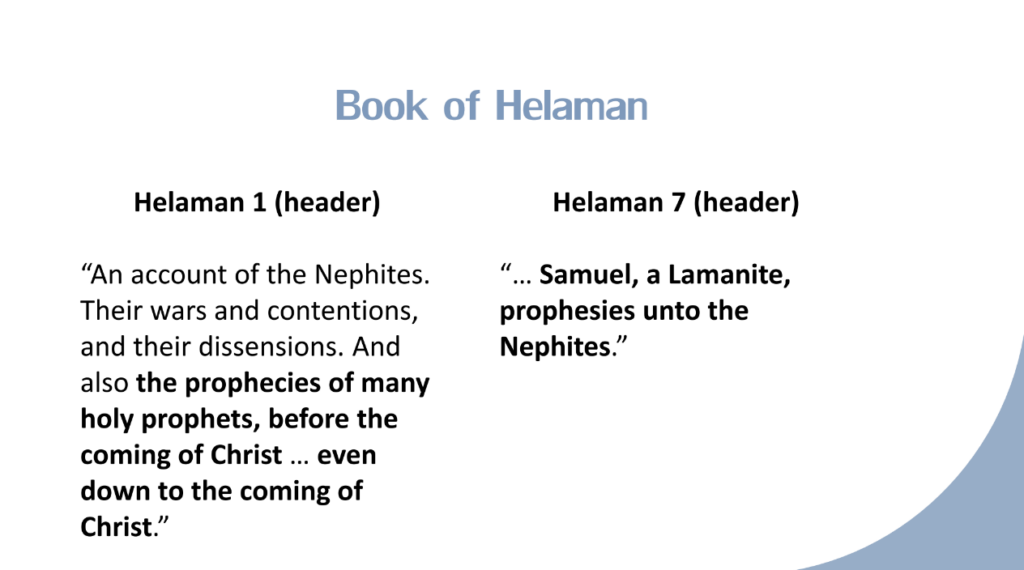

The ancient header found at the beginning of the Book of Helaman gives the following colophon or editorial preview:

An account of the Nephites, their wars and contentions, and their dissensions, and also the prophecies of many holy prophets before the coming of Christ, even down to the coming of Christ.”

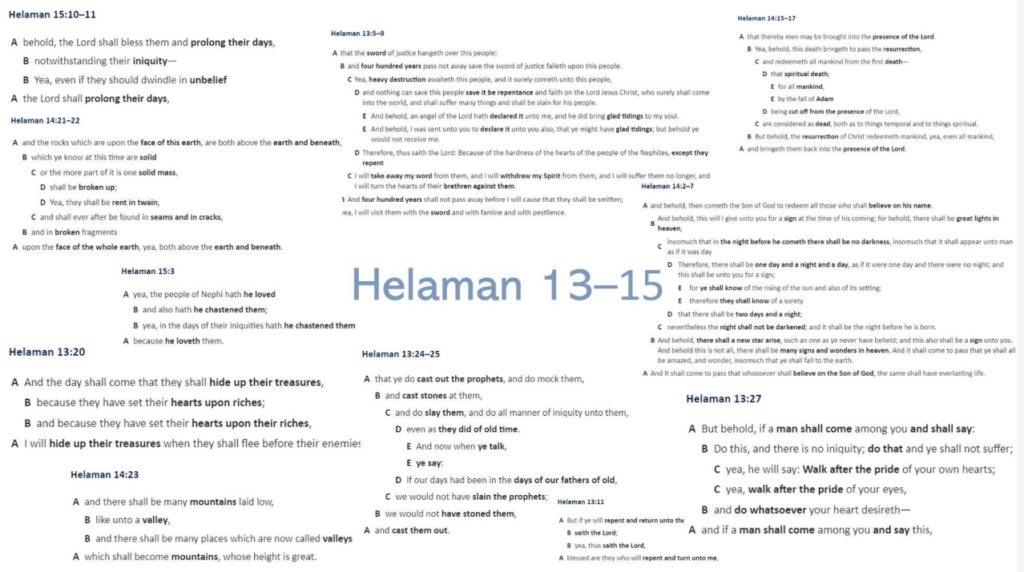

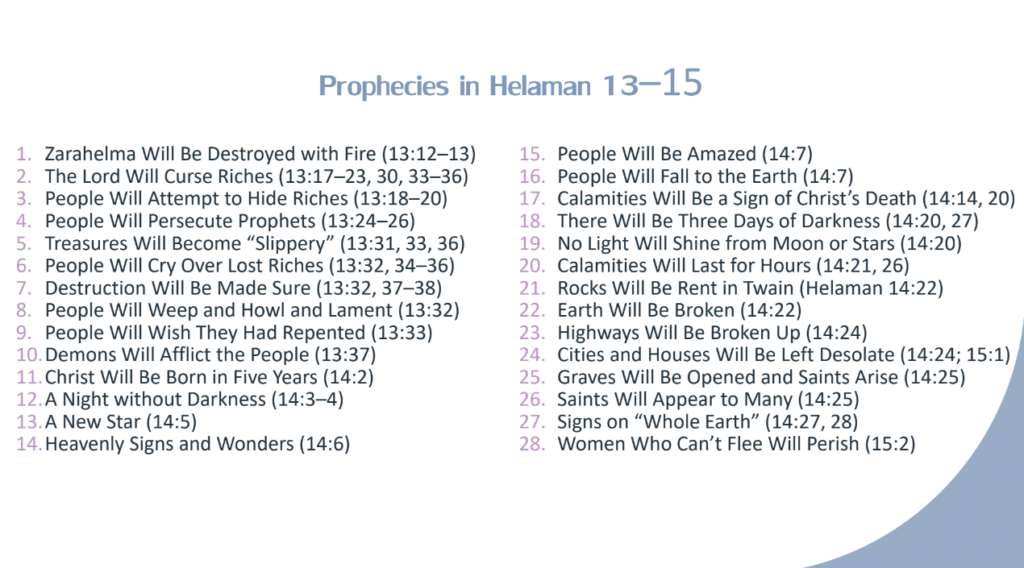

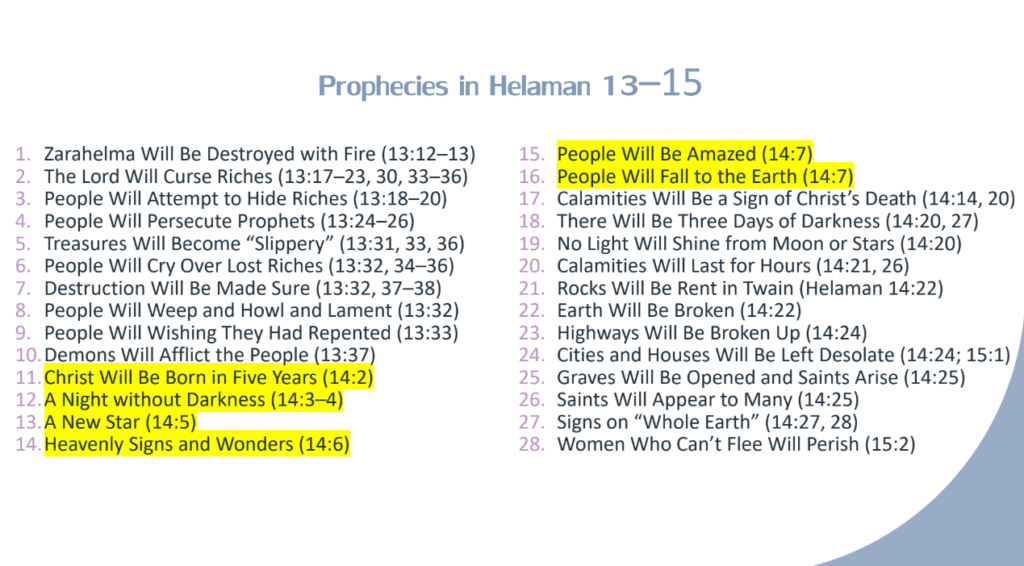

Several chapters later, the header in Helaman 7 declares, “Samuel the Lamanite prophesies unto the Nephites.” These separate editorial previews are either partially or completely fulfilled by Samuel’s prophecies found in Helaman chapters 13 through 15, which contained more than 10 chiastic proposals as identified by Dr. Donald W. Perry.

Convergence

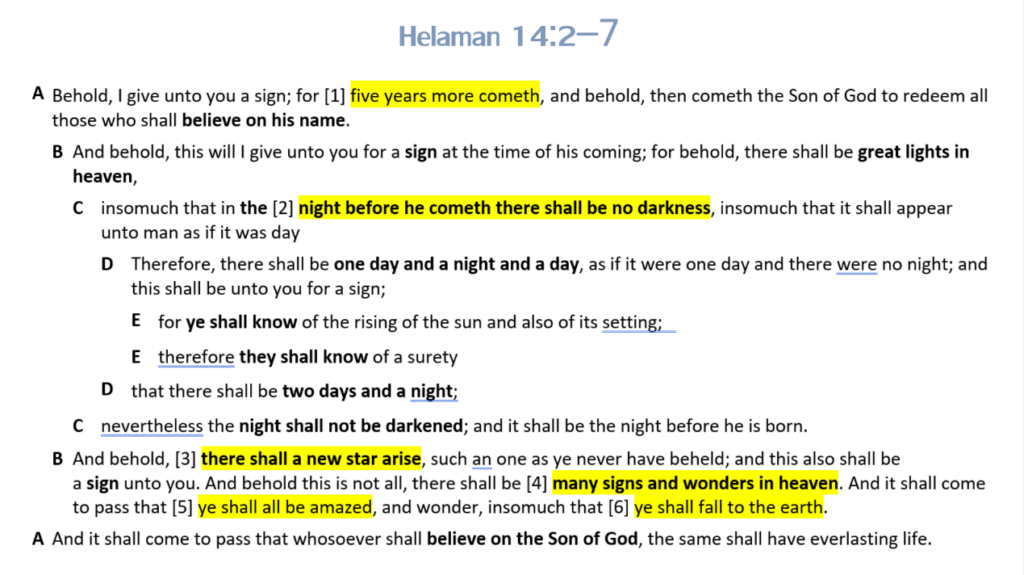

One example of this type of convergence can be seen in Helaman chapter 14, verses two through seven.

The chiasm presented in these verses contains six distinctive prophetic pronouncements highlighted in yellow, namely, that Christ will be born in five years, a night without darkness will be a sign of Christ’s birth, a new star will be a sign of Christ’s birth, many signs and wonders will be in heaven, people will be amazed, and people will fall to the earth. I’m paraphrasing there, that’s not the exact language.

You’ll notice that some of these prophecies are elements of the chiasm, which are bolded, while others are not. Remarkably, each of these six prophecies, along with all others that Samuel declared throughout these chapters, and many of the other chiastic proposals, are fulfilled in later chapters of the Book of Mormon.

Chiastic Complexity

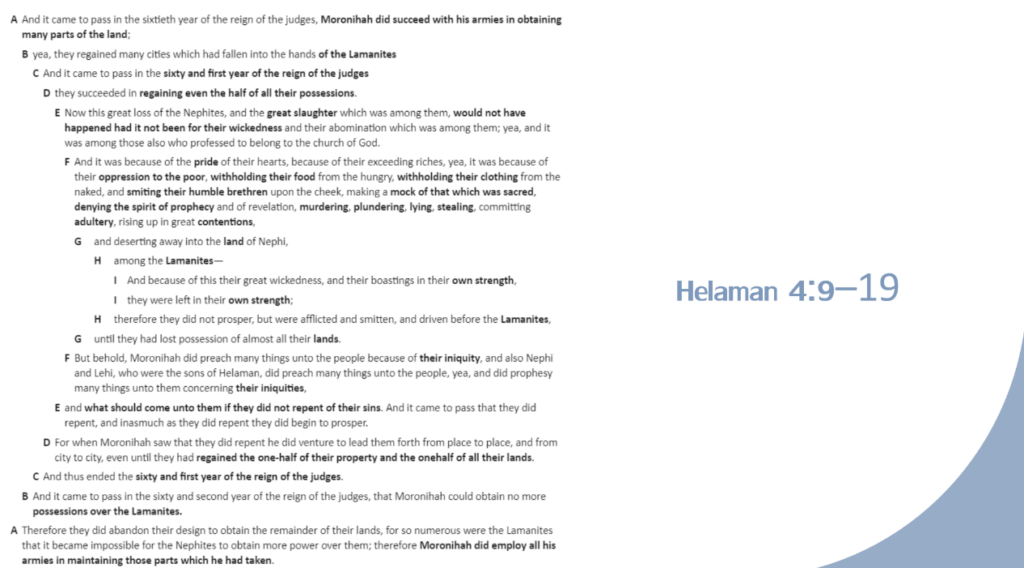

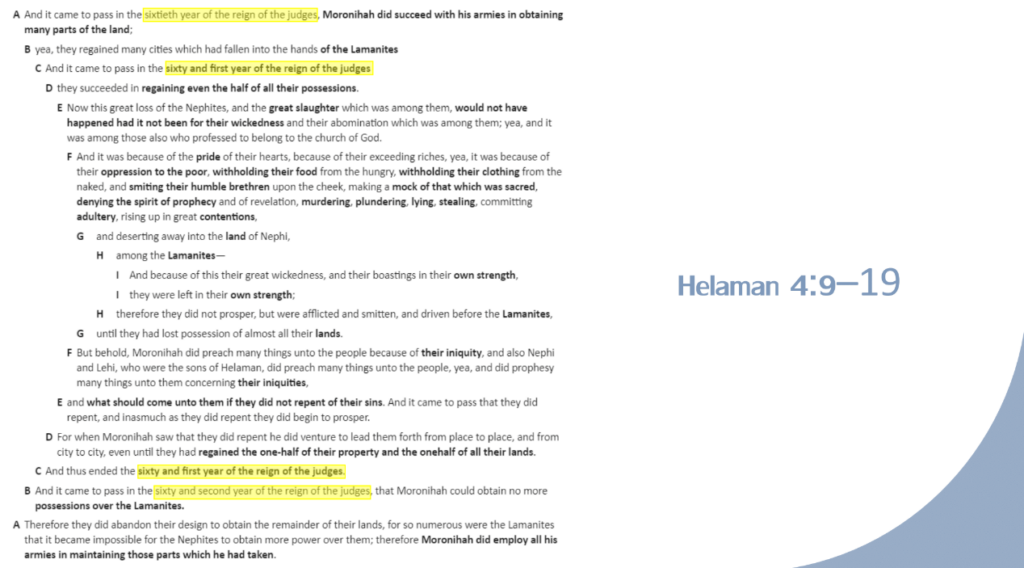

Another example of the Book of Mormon’s chiastic complexity involves a historical overview found in Helaman chapter 4, verses 9 through 19, which contains a fairly elaborate nine-layer chiastic proposal. Rather than highlighting editorial promises or fulfilled prophecies, this example concerns chronology.

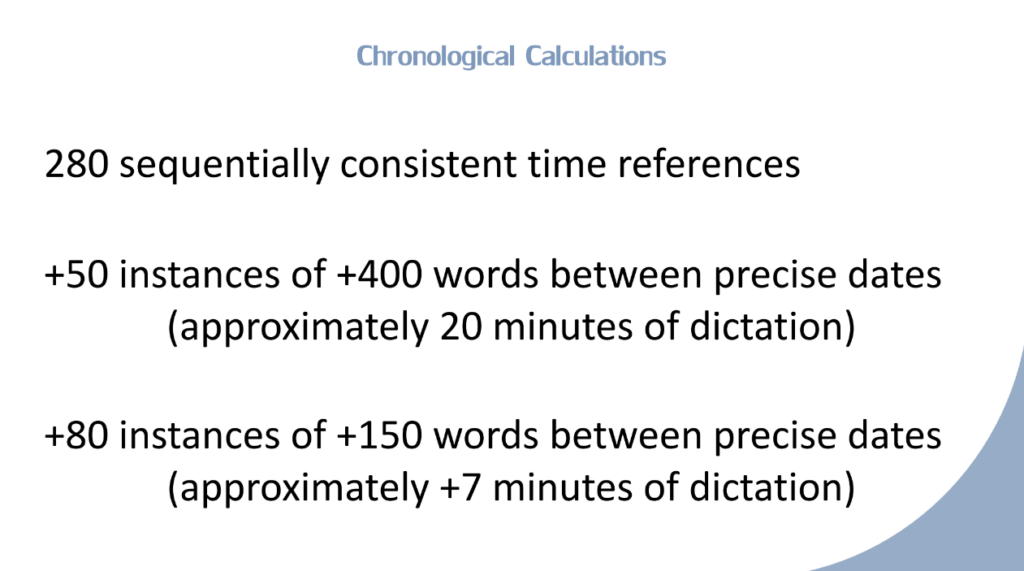

According to my count in a study I recently conducted (which hasn’t yet gone through peer review), the Book of Mormon contains at least 280 sequentially significant and consistent references to time. Many of its time markers relate precisely to the immediately preceding year, in the sense that they report on a later part of the same year or the very next year. Yet at the same time, many dates are also separated by substantial amounts of text.

Impressively, I discovered that in more than 50 instances, Joseph Smith dictated a chronological marker that precisely relates to the previous one, even though it’s separated by 400 words or more of text. Based on calculations made by John W. Welch in translation experiments that he and others conducted, that would correlate to about 20 minutes or more of elapsed time in the dictation process.

If you reduce the text distance to 150 words or more, you get more than 80 examples of Joseph accomplishing this same feat, which would correspond to about seven minutes or more of elapsed time during the dictation process.

Translation

To explain this, you have to remember that according to historical reports, Joseph would slowly dictate a line of text, probably about 20 to 30 words at a time to a scribe. After which, the scribe would write those words down and read it back to Joseph for verification. If any transcription or spelling errors were noticed, they would be corrected, and then the process would move on, never to return back.

This means that if Joseph dictated a date in one passage and then 400 words or more later, he dictated another date. He would have to recall what the previous year was after about 20 minutes or more of elapsed time. Not to mention all the intervening content, as well as the disruptions inherent in the translation process.

In some cases, Joseph would have had to remember a precise date after multiple days had elapsed. Yet, as far as I’ve been able to discern, the Book of Mormon’s chronology is sequentially consistent throughout the text, meaning that it never gives a date and then backtracks to a previous date after time and events had elapsed. So the one time I thought for sure that I had spotted a discrepancy, it was actually because I had made a transcription error and not a problem in the text.

Example in Helaman

With that in mind, this chiasm from Helaman in chapter 4 is noteworthy because it contains four sequentially consistent dates, two at the beginning of the chiasm and two more at the end with more than 300 words of intervening text.

In other words, in this case, the burden of dictating a complex chiastic structure doesn’t seem to have hampered Joseph Smith’s ability to simultaneously produce sequentially precise and consistent dates. I now frequently ask myself if I remember what the last date was in the text. Most of the time, I have no idea, yet somehow Joseph Smith never got it wrong, even when the chronology is interwoven among other complex types of data, such as chiasmus.

Alma Example

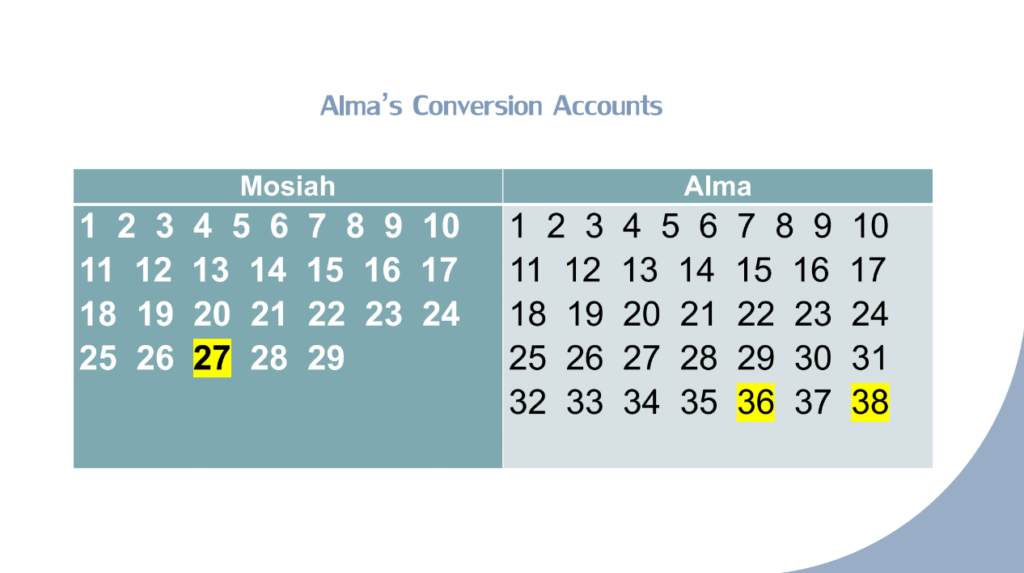

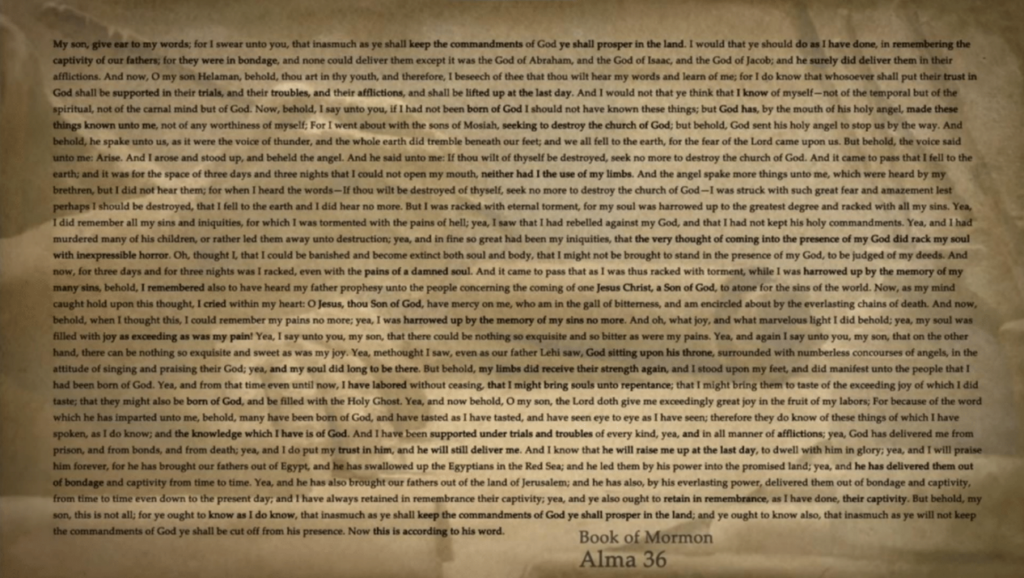

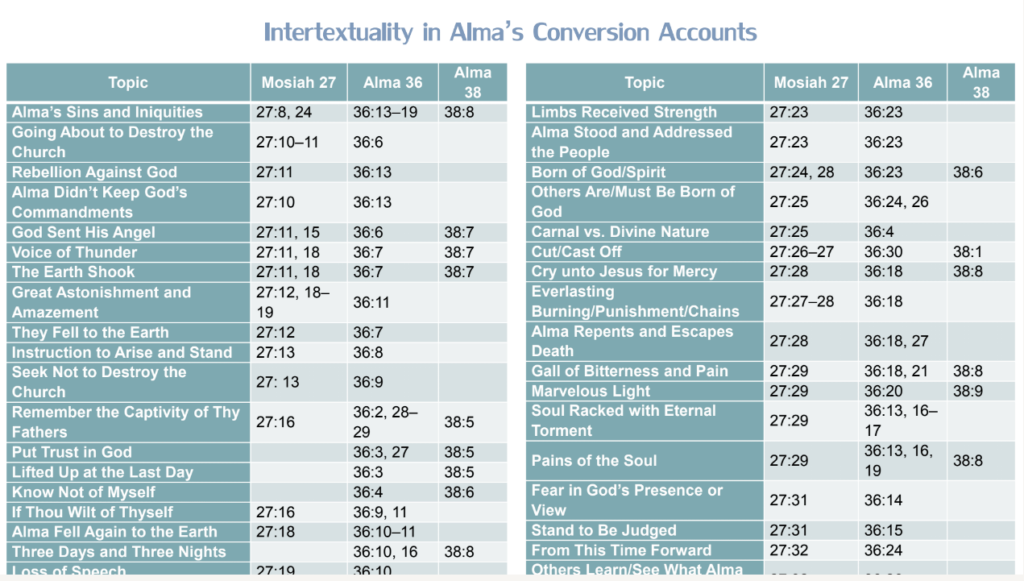

A final instance of chiastic-related complexity can be seen in Alma’s separate narrations of his conversion experience. The first conversion account recorded in Mosiah 27 is a summary provided by Mormon. This telling contains at least one noteworthy chiastic proposal found in verses 24 and 25. The final retelling is the shortened version that Alma gave to Shiblon in Alma 38.

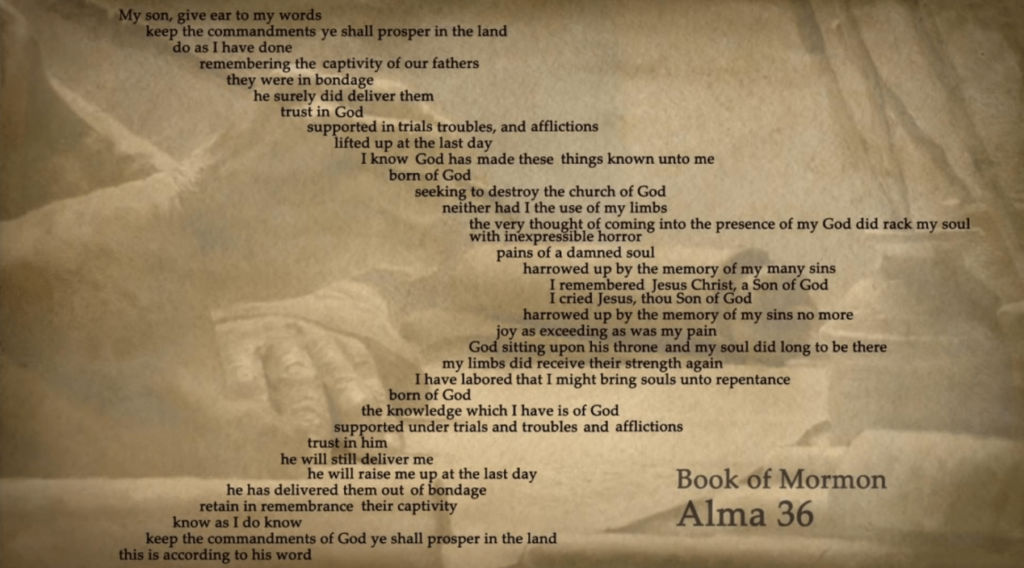

Alma 36 is widely regarded as the most remarkable chiastic structure in the Book of Mormon. What most readers have never considered is that this chapter is impressive not only because of its chiasticity but also because, at the same time, it’s textually consistent with Alma’s other retellings of his story.

In my study on this topic, I discovered that in 39 instances, the account in Alma 36 is consistent with the details, and in many cases, the wording that is found in the other two conversion accounts, with the bulk of the similarities being shared between Mosiah 27 and Alma 36. And by the way, these charts, I think, are all on Evidence Central, so you can take pictures of them or you can just visit the website.

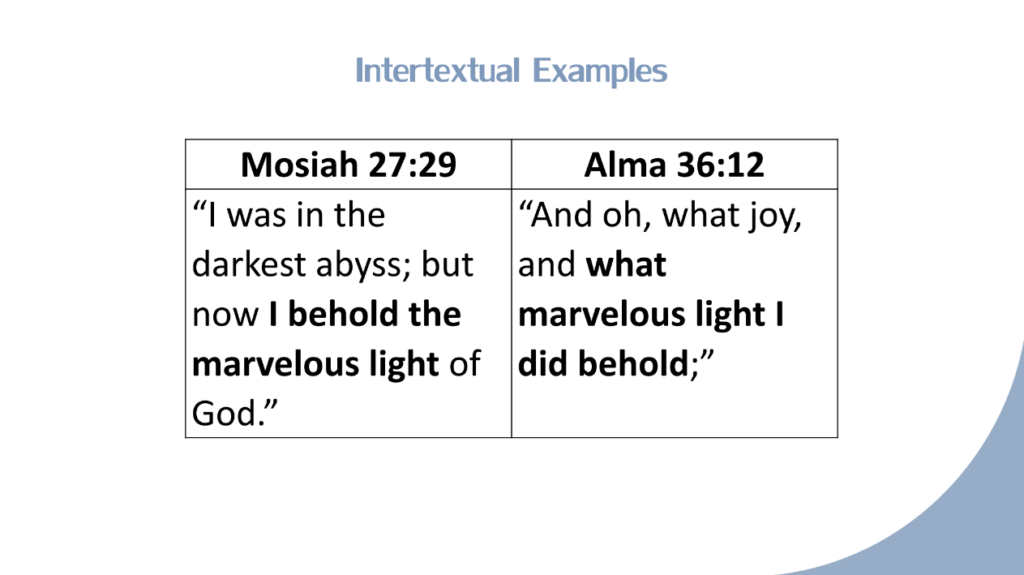

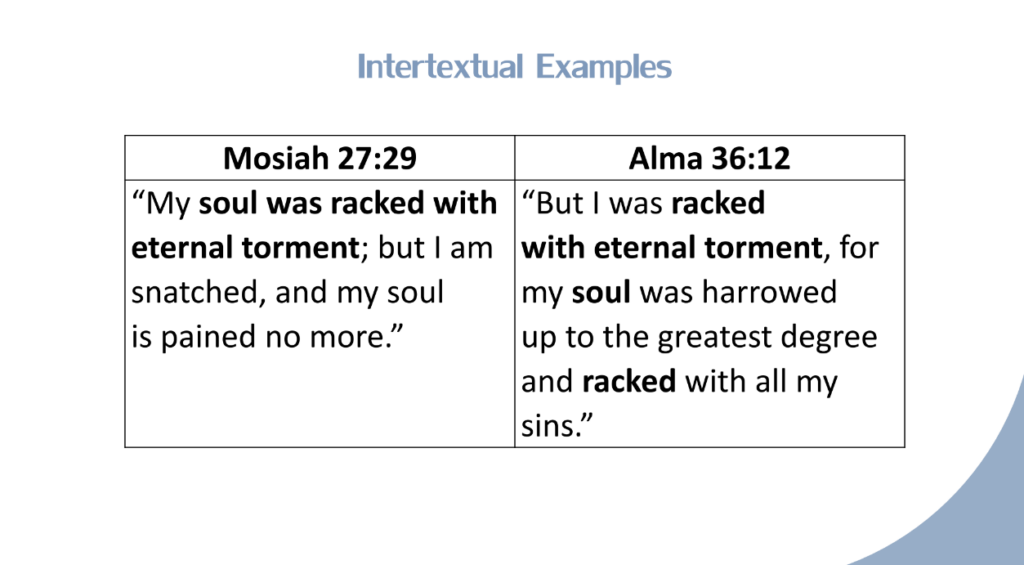

In the earlier account, Alma also mentioned that his soul was racked with eternal torment. Then, in Alma 36:12, he made a clearly similar statement, “I was wracked with eternal torment, for my soul was harrowed up to the greatest degree and racked with all my sins.”

We don’t have time to go through all 39 instances of textual similarities, but hopefully, you get the idea. The point I’m trying to make here is that in the process of dictating one of the most elaborate and remarkable instances of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith also rattled off 39 specific details that correlate with the other renditions of Alma’s conversion story.

Correlations

Particularly impressive is that the bulk of these correlations (35 of them) are shared between Mosiah 27 and Alma 36, which are separated by more than three dozen chapters. As summarized by John W. Welch,

Despite the fact that Mosiah 27 is separated from the accounts in Alma 36 and 38 by the many words, events, sermons, conflicts, and distractions reported in the intervening 100 pages of printed texts, these three accounts still profoundly bare the unmistakable imprints of a single distinctive person who, throughout his adult lifetime, had lived with, thought about, matured through, and insightfully taught by means of his powerful and beautiful conversion story.”

Summary of Evidence

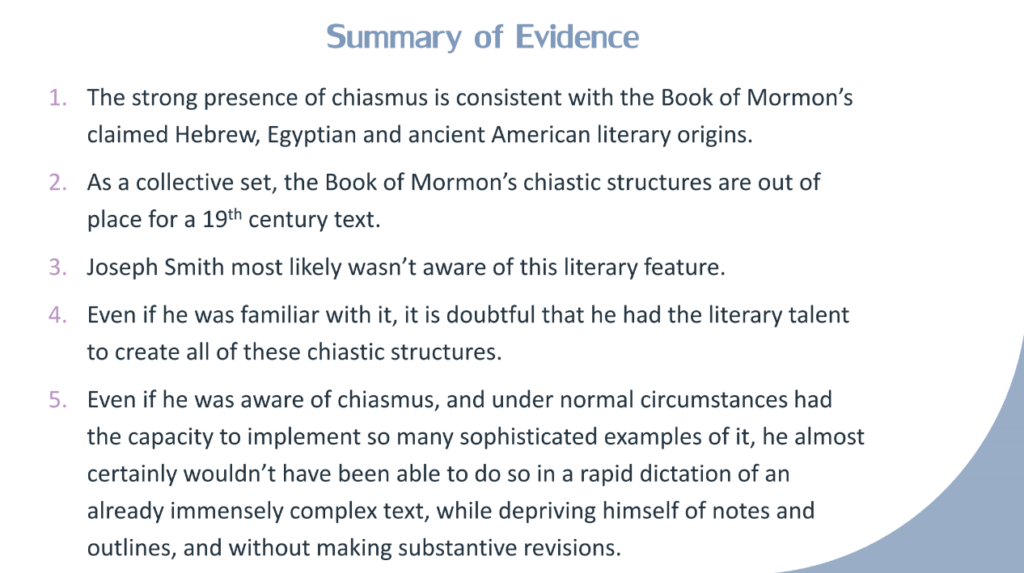

So, in summary, when we look at a feature like chiasmus, we can’t just approach it through a one-dimensional lens. We need to recognize that: one, the strong presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon is consistent with its claimed Hebrew, Egyptian, and ancient American literary origins; two, that as a collective set, the Book of Mormon’s chiastic structures are out of place for a 19th-century text.

Three, that Joseph Smith most likely wasn’t aware of this literary feature; four, that even if he was familiar with it, it’s doubtful he had the literary talent to create all of these chiastic structures; and five, that even if he was aware of chiasmus and, under normal circumstances, had the capacity to implement so many sophisticated examples of it, he almost certainly wouldn’t have been able to do so in a rapid dictation of an already immensely complex text, while depriving himself of notes and outlines and without making substantive revisions.

Thus, while chiasmus may be good evidence on its own terms, its persuasiveness is significantly amplified when viewed in conjunction with other categories of evidence. The interfaces being developed by Evidence Central are aimed to help people better recognize these types of mutually supporting relationships. If you want to learn more about chiasmus in particular, I would invite you to visit the evidence summary on this topic on our website.

Evidences and Faith

Yet, rather than being the source or foundation of faith, we hope that a better recognition and understanding of the available evidence can foster an intellectual environment where the spirit can more easily flow into an individual’s heart without being constrained by unnecessary skepticism or disbelief. It should almost go without saying that every faith journey is unique. We all approach religious claims with different backgrounds, different strengths and weaknesses, different interests, and different ways of thinking and processing information.

The stumbling blocks to faith are likewise diverse. Some things that are concerning or disruptive to one person’s testimony may be inconsequential or even irrelevant to another’s. We recognize that Evidence Central is not a panacea for every faith crisis. It won’t remove every reason for doubt; it won’t answer every unresolved question. But I think it does help shed light on all the possible questions that might be asked.

Many so-called exit narratives, those who have withdrawn their association with, or simply their belief in, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, report that seeming contradictions and unresolved questions played a large role in their loss of faith. As a standard narrative goes, for a while, the believer tries to deal with these doubts by simply placing them on the metaphorical shelf. But the shelf eventually becomes so burdened by unresolved questions that it, and by symbolic association, the believer’s testimony eventually shatters under the weight.

Questions Don’t Disappear

It should be recognized, however, that questions don’t simply disappear when one transitions from belief to disbelief. In the Restoration, for instance, those in doubt might ask why there are so many complex chiastic structures in the Book of Mormon, or why other people, in addition to Joseph Smith, testified that they saw the gold plates and the angel who delivered them into his possession. Or why the accounts of destruction in 3rd Nephi are so consistent with documented volcanic catastrophes, or why the Book of Mormon’s legal cases so often seem to be informed by and interact with ancient Near Eastern legal concepts and precedents. Or why the monetary system presented in Alma 11 is complex, elegant, and has parallels with ancient systems of weights and measures.

Or why Nephi’s account of his family’s journey connects so well to the known geography of the Arabian Peninsula. Or why King Benjamin’s speech correlates so well with ancient Near Eastern festivals and ceremonies. Or why Jacob’s allegory of the olive tree betrays an intimate knowledge of genuine olive culture. Or why so many names in the Book of Mormon are either attested in ancient languages or are associated with plausible Hebrew and Egyptian wordplays or puns. Or why statistical linguistic analysis of the Book of Mormon, which we will learn more about, I believe, after my presentation, strongly points towards multiple authorship and away from Joseph Smith as being its author, consistent with his claim of only being its divine translator.

The list could go on and on, but hopefully, you get the idea. It’s hard, at least for me, to explain these and many other features of Joseph Smith’s revelations without appealing to divine intervention, especially when they’re looked at collectively. Stated simply, giving up faith in the Restoration doesn’t make unresolved questions go away; it merely transitions the burden from one set of perplexing questions to another. In some cases, an individual’s struggle with doubt may, at least in part, be a symptom of an unbalanced focus on questions that arise from criticisms of the Restoration while neglecting those that attend the multitude of evidences for its authenticity.

God’s Intentions

More importantly, however, we might ask ourselves, in the first place, if God ever intended to tie up every loose end of doctrine, practice, or policy so that no important questions or perceived inconsistencies remain. In other words, should we expect God to remove the very conditions that make faith not only possible but, in some cases, necessary? Such an assumption seems to overlook a fundamental purpose of mortality. A big part of why we’re all here is to see how we spiritually respond in an environment of uncertainty, a condition that has been specifically tailored to test our faith.

Unresolved questions and concerns may look quite different when they’re viewed as a necessary and even essential part of God’s plan rather than some unexpected aberration. What I personally expect from God is that, in addition to leaving plenty of room for doubt and disbelief, he will also grant us ample and sufficient reasons to believe. After all, completely blind faith—meaning to believe in something for no good reason at all—would be neither logical nor spiritually beneficial. Reasons matter; rational thought is an integral part of any testimony.

Faith Struggles

For those who are struggling with faith, it may be helpful to spend less time agonizing over unresolved concerns and questions and to spend more effort and energy trying to understand and appreciate the greatness of the evidences, both spiritual and secular, that God has already made available. At the very least, the information being offered by Evidence Central can provide a robust counterbalancing effect in contrast to any reasons for doubt that one may encounter. An intimate awareness of the available evidence supporting the Restoration will likely result in a much more balanced environment of investigation, where no one should feel intellectually compelled toward either belief or disbelief.

Hopefully, in such a setting, individuals will be more inclined to fully and repeatedly engage in the spiritual experiment outlined by Alma in his famous discourse on faith, allowing the Holy Spirit to act as the ultimate arbiter of truth. And that’s really our primary goal at Evidence Central. We want to encourage people to turn to God with more faith and more hope and with more trust and with less doubt and with less skepticism and with less disbelief than ever before, so that they can get the answers that they need most from the source that matters most.

We hope that you explore this new resource for yourself, become familiar with what it offers, and share it with any family, friends, or scholarly associates who might also benefit from its use. We plan to continue to add new evidence articles and new interfaces and to refine Evidence Central on its various platforms as we go along.

In my experience, there will always be another reason to believe, sometimes from the most unexpected sources. We just have to keep looking. Thank you for your time.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you, Ryan. So first, I have to apologize for mispronouncing your name. In my defense, we have someone in our stake that spells the name exactly the same and pronounces it differently, so I just made a bad assumption. I apologize for that.

Ryan Dahle:

That’s okay. I get that a lot, so I’m very used to that by now.

Scott Gordon:

Yeah, I understand. So, you spoke a lot about chiasms and wonderful evidences in the Book of Mormon. I’m going to rephrase a question. I think you probably already answered it in your presentation, but I’m going to present this question sent in to us: If someone comes up and asks you what is the one thing, the one evidence that you would give if you could only give one about the Book of Mormon, what would it be?

Ryan Dahle:

I’ve actually thought about that quite a bit, and the longer I’ve done research on different types of evidence, the more convinced I am that there isn’t really a single silver bullet. There’s no smoking gun; there’s no single evidence that is going to persuade anyone to accept any of these claims. They all have different strengths and weaknesses. All evidences have different assumptions that are fundamental to their validity that you can’t prove. And so, I don’t think there is a single evidence that we should hold up on this pedestal as being so much better than the others. They all have different strengths and weaknesses.

I would say the types of converging evidences, for example, where something that seems to be ancient, that seems to be beyond Joseph Smith’s ability to have produced, but that’s also complex. I think those types of convergences are really powerful. I’ll give another example. As Lehi’s family travels down through Arabia, eventually they come to a place which was called Nahom, and that seems to correlate with a region in southwestern Arabia. So, there’s good geography, there’s good archaeology supporting that. But at the same time, there’s also wordplay associated with Nahom that’s been studied and put forward. And so, those types of convergences, when they all come together, are really powerful for me.

But it’s not just one thing. It’s not just that there have been inscriptions on stones that help date that particular toponym to that particular time and place. It’s that, combined with the convergence of their trip through Arabia and its location simultaneously in relation to Bountiful and in relation to Shazar and the Valley of Lemuel and the intervening details through that trip. So, in a nutshell, I would say there’s no single evidence that’s the best, but I like convergences of evidence.

Scott Gordon:

Excellent. Are these evidences going to be only in article form, or are you going to put them in other formats as well?

Ryan Dahle:

As mentioned in the presentation, we’re developing a YouTube series that will present them in another format. I don’t know exactly what the future will hold; we’re developing different interfaces to navigate evidences differently. But some of those interfaces may help you view particular evidences in ways you’ve never thought of before. So, yeah, I would say we definitely plan to have different formats of presentation for our upcoming evidences.

Scott Gordon:

It’s an interesting question here. Will you publish on spiritual evidence of the restoration, metaphysical, philosophical, or are you going to stick mostly with historical?

Ryan Dahle:

I don’t know for sure. It’s kind of hard to define spiritual, but I guess there’s the reception history of the Book of Mormon and how it’s affected different people’s lives or the way that the text has influenced the world. But yeah, I would say mostly we’re going to be sticking to archaeology and geography and linguistics and literary studies and biblical studies and those types of things. But every once in a while, I think that we would definitely be open, if those things are amenable to what we’re trying to accomplish.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you so much for your time and your efforts at Evidence Central and coming to speak to us.

coming soon…

Is there a single strongest piece of evidence for the Book of Mormon?

No single “silver bullet” exists, but the convergence of multiple lines of evidence provides a compelling case.

How does Evidence Central differ from traditional apologetics?

It focuses on presenting positive evidence rather than responding to criticism, allowing users to explore faith-supporting research in depth.

The role of converging evidence in strengthening testimonies.

The importance of making scholarly research accessible to a faith-based audience.

Balancing intellectual inquiry with spiritual confirmation.

Share this article