August 2021

Introduction by Scott

Our next speaker is Ben Spackman. We were just comparing notes. Ben Spackman ended up becoming a FAIR volunteer when he wrote a critical email into us. And I suggested he join and so he did. So that was good. Ben Spackman is a PhD candidate in American religious history at Claremont. His dissertation examines the intellectual roots of LDS creationism and evolution of the 20th century. Prior to that, he received a master’s degree and a PhD work in Old Testament Languages and Literature at the University of Chicago. He’s a guest editor of a special forthcoming edition of BYU Studies. And there’s more you can read if you’d like. But with that short introduction, here’s Ben Spackman. Thank you.

Ben prefers to speak extemporaneously with his slides instead of reading a paper, resulting in a more conversational presentation. This transcript has been edited for reading.

I’m glad to follow Jeff Thayne’s presentation yesterday on worldviews and assumptions, and how we unconsciously adopt them as well as Keith Erekson’s discussion of reading history and scripture in context, those dovetail nicely with my topic.

I’m a historian. I study change in the past, I try to understand what changed and why. And then I try to help explain those changes. I want to start today with a couple examples of some startling changes in the last 150 years or so. Then I’m going to spend the rest of my time explaining them as best as I can in 45 minutes, but we are skimming across a lot here.

So, to begin, in April 1932 General Conference, President Heber J. Grant said, “I rejoice that we are fundamentalists.”[1] We don’t talk like that in General Conference anymore. What did he mean?

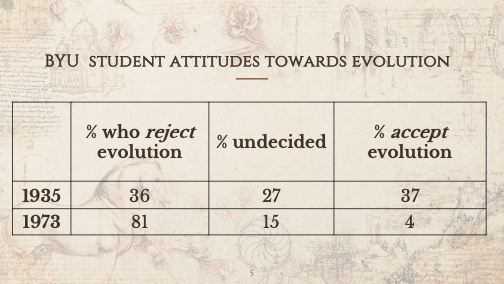

Startling change #2. In 1935 there was a poll taken of BYU students regarding evolution, about equal numbers rejected and accepted evolution way back in 1935. And there was also a good bit of the undecided crowd. Now a lot happens at BYU between 1935 and 1973. Evolution gains a lot of scientific evidence, BYU grows in size and hires a lot more science teachers, and starts dedicated evolution courses. You might expect the acceptance rate among BYU students to go up. “It did not,” said the voiceover. Rejection of evolution almost doubles,*[2] acceptance drops by a factor of nine and there are far fewer undecideds. This shifts heavily to the “reject” stage and people are not really wishy washy about it.

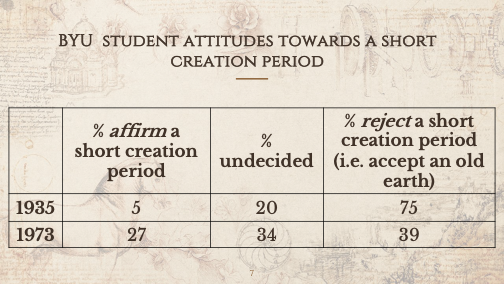

Number three, in 1935 75% of BYU students reject a short creation period. That is, they accept that the earth is old, that it took a long time to create. Only 5% affirm a short creation period, 20% undecided. By 1973, like evolution, that goes in a surprising direction, far more BYU students are in the young earth or undecided category. How does that happen?

Number four. This is Charles Hodge, a prominent guy at Princeton Theological Seminary through the late 19th century. He helped pioneer modern Protestant ideas around fundamentalism and inerrancy. He said, very bluntly, “evolution is atheism.”

Not mincing words. And yet as we go through the 20th century, what we find is a number of prominent Christians across the spectrum, who accept or are open to it: several Popes,[3] CS Lewis,[4] Billy Graham,[5] evangelical scientists like Francis S. Collins,[6] who ran the Human Genome Project and is the current director of the National Institute of Health. We also find evangelical Bible scholars who accept and proclaim inerrancy, who also accept and proclaim biological evolution of humans.[7] How do we get from evolution is atheism to inerrancy earnest evangelical Bible scholars proclaiming evolution? To be clear, these people are not atheists.

Number five, here’s William Bell Riley, the Grand Old Man of fundamentalism, founder of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, and editor of The Christian Fundamentalist (here we have that F-word again). He says in the 1920s, there is “not a single intelligent fundamentalist who claims that the Earth was made 6000 years ago, and the Bible never taught any such thing.”[8] Now, you might argue that the adjective “intelligent” is doing a lot of excluding work there. But studies have shown that young-earth creationism (YEC) was extremely rare in the early 20th century. Riley is asserting the predominance of the old-earth position here, even among the fundamentalists. Now compare that to a 2013 study that said roughly 10% of Americans assert a young earth creationist position that’s on the order of tens of millions of Americans in 2013 believe that the earth is young.[9]

There are several stories of change here: fundamentalism, understandings of Genesis, acceptance of evolution, the spread of young-earth creationism, LDS views, and science. What is the unifying thread in these stories? What are the main ideas? Well, first, whether in science or religion, the position one takes on an issue depends on one’s interpretation of the available data, and the interpretation you give is based heavily on the assumptions and presuppositions you bring to that.[10] Second, there are changing and competing understandings of Science as well as scripture, and I don’t mean scientific data changing our views, I mean, understanding the nature of Science itself.[11] And third, the primary mover in this story is not science, but assumptions about the nature of revelation, scripture, and interpretation.

I want to elaborate on that slightly, because it’s not the narrative we hear in non-technical press, in mainstream press. What drives religious opposition to evolution, and what reduces opposition to evolution, is not science or scientific argument, even though the public arguments often take that form.[12] Ken Ham, and Bill Nye arguing about cell structure and such doesn’t change anyone’s mind, doesn’t convert anyone. Rather, creationists are motivated by a desire to be faithful to Scripture. That’s it. That’s the bottom line. (See Q&A for further on this.)

Now, that raises some key questions that we rarely discuss at all in the church, namely, what is the nature of scripture? And how should we interpret and understand it? Is scripture a superhuman encyclopedia of divinely revealed facts of history, science, and doctrine? Is it an entirely human book, which I don’t think is an option for Latter-day Saints? Is it some combination of human and divine? And if so, how and in what measure? I’ve argued pretty strongly at FAIR for position number three. But how should we interpret scripture once we’ve talked about the nature of it? Do we just read it at face value? Do we need context? If so, how much, what kind, where do we get it? These questions about the nature of Scripture and interpretation are part of a field scholars call “hermeneutics,” another word (and topic!) we don’t hear very often in the Church.

So with that out of the way, let’s start with a brief definition and history of evolution. By biological evolution, I mean “common descent,” i.e. that modern species like humans and apes share and have diverged from a common ancestor. I contrast that with “special creation,” i.e. the magic-wand instantaneous creation of animals, including Adam and Eve, in their modern forms.[13] Now, evolutionary ideas, sometimes called “transmutation of species,” long predate Darwin; he did not invent evolution.[14] You have some Catholic theologians way back in the 13th century, with developmental ideas. You have Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was a major competitor to Darwin in terms of ideas about evolution, even though he dies before Darwin puts out his work. Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus wrote and spoke about evolution, he wrote poetry about it. And then we have a book by Robert Chambers that he wrote anonymously, published in England in 1844, called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation[15] that was strongly evolutionary and generated all kinds of discussion, mostly in England because America was busy.

What Darwin contributed himself in his 1859 book— On the Origin of the Species— was a mechanism for explaining how species might change. He called that mechanism “natural selection,” which I’m not going to spend time on. After Darwin proposed his mechanism in 1859, America was again kind of busy (i.e. the civil war). There are other things going on in England, and we get a period that has been called the “eclipse of Darwinism” which runs through the 1920s.[16] During this period of “eclipse,” Darwin’s data essentially convinced many scientists that evolution had indeed happened, including human evolution. However, there were some good scientific reasons at the time for thinking that Darwin was quite wrong about natural selection.[17] And so this eclipse of Darwinism is essentially a period characterized by “evolution, yes; but Darwin and natural selection, no.” If you’re not reading the literature carefully in this time period, if you assume that “Darwinism” is the same as “evolution,” it’s easy to get the idea that “scientists are rejecting evolution now.” And this runs through the 1920s, the early 1930s. What gets us out of the “eclipse of Darwinism” is this thing called “the modern synthesis.”

This synthesis draws on the rediscovery of Polish monk Gregor Mendel’s work with pea plants about inheritance and some other things. It’s then augmented heavily in the 1950s, with the discoveries around DNA as the mechanism for passing on traits, and its double-helix shape. That’s all I’m going to say, on that side of things, but it is important.

Let’s talk more generally about science; “science,” as we understand it today was invented in the 19th century. That may be news to some of you who think that science is a fixed idea and standard that goes back into the 1600s or further. So what exactly do I mean? Well, first of all, in terms of terminology, British scientist William Whewell coined the term “scientist” in 1834.[18] And it takes several decades to catch on, he kind of coined it as a joke, almost. But they didn’t know what to call such people, who were becoming more and more frequent.

And what I mean by “such people” is that over the nineteenth century, science became 1) a profession. It was something you did as a job; you could be employed as a scientist. It became 2) specialized, you tended to do one thing deeply, instead of skimming across physics, chemistry, biology, zoology, geology, as had been the case in the past. It became 3) technical,[19] it became 4) quantifiable, and it became 5) secular.[20] The nineteenth century is when the people we think of as scientists, even though the vast majority are deeply believing Christians, start getting away from saying, “Well, God did it” as a kind of explanation.[21] What they are looking for is the natural mechanism, the natural law, that God uses to do these things.[22] They are trying to discover the laws God put in place. So they start separating out theology from science.

One other important characteristic— nineteenth century science retained an extreme Baconian character. Now, some of you may have just perked up because I said “bacon.” I regret that I’m talking about Sir Francis Bacon, the father of empiricism. The Baconian idea of science was, in essence, “we need to get away from all these Aristotelian ideas about qualities and we need to go out and we need to catalogue stuff, we need to measure things, we need to gather all the facts, you can’t know anything until you’ve gathered all the facts.” As one historian notes,

In the 19th century, Bacon’s name inspired in Americans and almost reverential respect for the certainty of the knowledge achieved by careful and objective observation on the facts known to common sense.[23]

Now, one of the problems with Baconian ideas of science in the 19th century was that it didn’t like drawing conclusions from facts, it didn’t like saying, “Well, here are all the facts, and they point in this direction.” It didn’t like theorizing things that couldn’t be pointed at or measured or demonstrated in a lab.[24]

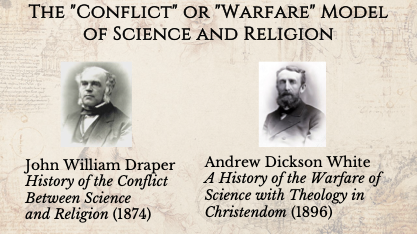

Now, in the 19th century, as science starts rising and gaining a lot of authority— people start thinking of science as the main way of knowing things, of legitimating knowledge— science comes into conflict with a much more traditional source of authority, namely religion. And two men at the end of the 19th century—Draper and White— create or popularize the idea that science and religion are both fixed concepts, and that throughout all of human history, science and religion have been at war with each other.

Frankly, both of their books were insanely popular and maybe part of that popularity comes from the fact that both books were really bad scholarship.

One effect of this claimed “warfare” model of science and religion, and the ascension of science, was that it created a cultural need to portray scripture and prophetic utterances as scientific in nature, and scientifically reliable. Think of John Widtsoe’s book in 1908, Joseph Smith as Scientist. Well, what does that do in terms of PR for Joseph Smith? If he’s prophetically anticipating science, then that is scientific proof of his prophetic ability; it’s “baptizing” or legitimating Joseph Smith’s authority with the authority of science in a way.

Draper and White and this “warfare” idea were terrible, but it became extremely popular, becoming the default cultural understanding.[25] The historian’s take is less friendly; look at this recent book’s subtitle on the Warfare model, “The Idea that Wouldn’t Die.” Historians are very unhappy with the cultural effect these two books had because in popular media, among students and many adults, the ideas and the assumptions that they propagated still remain very, very present in our thought processes.

Draper and White and this “warfare” idea were terrible, but it became extremely popular, becoming the default cultural understanding.[25] The historian’s take is less friendly; look at this recent book’s subtitle on the Warfare model, “The Idea that Wouldn’t Die.” Historians are very unhappy with the cultural effect these two books had because in popular media, among students and many adults, the ideas and the assumptions that they propagated still remain very, very present in our thought processes.

How many of you, for example, read or were taught as a kid that medieval Catholics thought the earth was flat and the sailors who went with Columbus were afraid of failing off the edge? How many of you? It is an absolutely false claim, as the historians know, but it was one of the false things popularized by these two writers. They attributed that idea to the Catholic Church; they both had very anti-Catholic axes to grind. So there’s this “warfare” idea, there’s “science” rising, there’s science and religion seemingly in conflict. And there is a perfect wave of a number of elements going into the early 1900s.

How many of you, for example, read or were taught as a kid that medieval Catholics thought the earth was flat and the sailors who went with Columbus were afraid of failing off the edge? How many of you? It is an absolutely false claim, as the historians know, but it was one of the false things popularized by these two writers. They attributed that idea to the Catholic Church; they both had very anti-Catholic axes to grind. So there’s this “warfare” idea, there’s “science” rising, there’s science and religion seemingly in conflict. And there is a perfect wave of a number of elements going into the early 1900s.

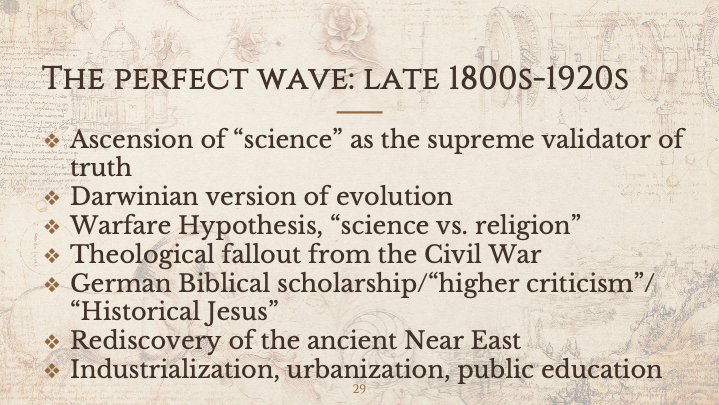

There is at that time 1) the ascension of science as the supreme validator of truth,

2) the Darwinian (and competing) versions of evolution,

3) the warfare hypothesis from Draper and White, science versus religion.

You also have 4) theological fallout from the Civil War.[26] Very briefly, the Civil War caused kind of a crisis of interpretation for Americans, because both sides use the Bible to argue opposite positions. And they weren’t merely theological abstractions. They were matters of life and death.

Add in 5) German biblical scholarship, “higher criticism,” historical Jesus scholarship. This had been around for a while, but it hadn’t really made it into America yet; it shows up after the Civil War and starts having a huge effect.

6) The rediscovery of the ancient Near East. Remember that Joseph Smith acquired some papyri and mummies in the mid-1800s. Well, the archaeologists— or looters, rather— did not stop there. The 1800s and 1900s saw the discovery of hundreds of thousands of texts and sites from the ancient Near East in Sumerian and Assyrian and Babylonian and Egyptian and other languages you’ve never heard of; many of these shed light on the Bible in some way. At minimum, there’s some kind of context brought. But some of them also have creation stories that sound very similar to Genesis, they have flood stories that sound very similar to Genesis.

And lastly, 7) there are the social and economic things happening, there’s a lot of industrialization, people are moving away from farms and into the cities. And as such, they’re getting a lot more public education, where the government is saying, “This is what you have to study in school.”

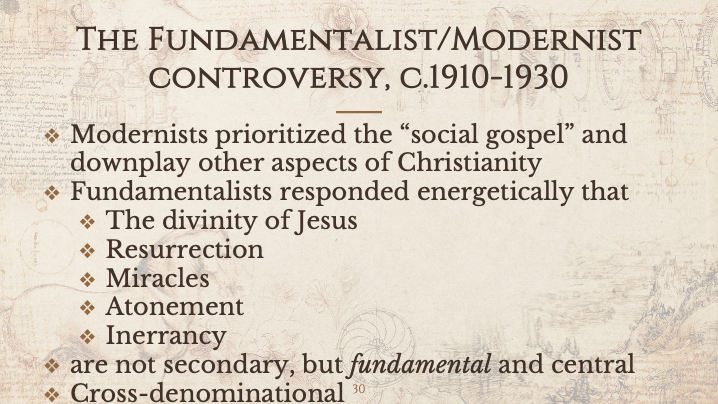

All of these factors lead to what’s called the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy.[27] And here’s where our F-word really arises in the history. Modernists reacted to all these things by prioritizing the social gospel and downplaying other aspects of Christianity. That is, they looked at all of those things I’ve just listed and said, in effect, “maybe the most important things that we do are how we live our lives, living charitably, taking Jesus as our example of discipleship. Let’s take care of the poor. Let’s start schools. And we won’t worry so much about things like atonement or miracles, etc. That’s not the central stuff of Christianity, anyway.”

Well, fundamentalists responded quite energetically that things like the divinity of Jesus, resurrection, miracles, atonement and biblical inerrancy weren’t really secondary aspects of the gospel. Those were, as the word says, fundamental. They were central, they were non-negotiables. Now, fundamentalism and modernism were cross-denominational, there was not a church called “fundamentalist.” The controversy split Baptists and Presbyterians especially, but you could also find Catholics who call themselves fundamentalist.

This is the general context in which President Grant had said, “we are fundamentalists.”[28] Now as Latter-day Saints, we can quibble with that inerrancy bit,[29] but otherwise, we line up very heavily with these specific fundamentalist elements, and are similarly unwilling to concede “these things are negotiable. We don’t need really them.”

This raises the question, what was not considered a “fundamental”? Perhaps surprisingly, 1) The age of the earth. Because the vast majority of American Christians in the early 1900s and 1800s thought the earth was old. They thought the Bible taught that.[30] 2) A worldwide flood— many Christians did not think the Bible taught a worldwide flood. Most thought it was local. And 3) evolution was also not one of these things centralized or emphasized in The Fundamentals, the title of a series of books written from 1910 to 1914 and published by two wealthy Californians and sent out to pastors all over the country. That’s where the word “fundamentalist” ultimately comes from.

In this series of essays called “The Fundamentals,” you find three, I think, on evolution. One’s a little ambivalent about it, one says, “Well, it depends,” and one is kind of “no sir we absolutely do not believe that.” And notably, the essay most adamant against evolution was written by a layman that had first been an editorial in a newspaper. The rest of these essays are written by well-known and highly trained scholars; Fundamentalism began as an academic and intellectual movement.

Now this was the case with evolution and similar topics, at least early on in the history of Fundamentalism. But after World War I, fundamentalism shifts; it becomes more populist and more anti-intellectual. (Fundamentalism, again, started as an intellectual University movement, a pushback against other scholars.) Along with this populism and anti-intellectualism, evolution starts becoming one of the primary and overriding concerns. It becomes the evil behind all other evils. The changing nature of science led to competing claims of “good science versus bad science” and claims that evolution was “not scientific.” Well, why? Again, historian George Marsden.

Fundamentalists resisted Darwin, but they were not opposed to science as such. Rather, they were judging the standards of the later scientific revolution by the standards of the first the revolution of Bacon and Newton. And their view, science depended on fact, and demonstration and Darwinism, so far as they could see was based on neither.[31]

So if you held to a Baconian understanding of the nature of science, the older view, you could make all these rhetorical arguments about how evolution was “bad” science. But if you were moving into the newer, more modern understanding of the nature of science, and the relationship between data and extrapolating from that data, you would say, “this is good science, but you’re kind of stuck in the past.”

This brings us to the 1925 Scopes Trial, over the legality of teaching evolution in public schools.[32] Now, what a lot of people don’t know is that the Scopes Trial started as a PR stunt for a small town in Tennessee. And unfortunately for them, it snowballed, and two of the biggest lawyers in the country came to volunteer their services. And if I remember the anecdote correctly, there was more radio coverage and newspaper print on this trial than anything that had ever happened in the country before.

Fundamentalism at the end of the Scopes Trial appears defeated. If you’ve ever seen Inherit the Wind, which is a 1950s play and then film about the Scopes Trial, it’s really trying to comment on the Red Scare, but they make it about the Scopes Trial.[33] It misrepresents what happened and gives you the wrong idea. Fundamentalism appears defeated but it was not. One effect of the Scopes trial is that science textbooks present evolution differently, until the 1960s. [34] at the college and high school level they remove evolution almost entirely. It disappears until the 1960s after Sputnik when they say, “oh, maybe we should be doing more science. The Russians are ahead of us. This is a problem.”

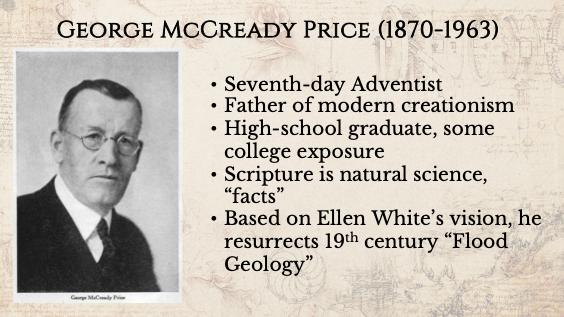

Fundamentalism, in fact, was not defeated. It goes underground.[35] It grows rapidly and explodes back into the public eye in 1961. What happens in 1961? To understand that, we need to go back to the earlier 20th century and talk about George McCready Price. Price was a Seventh-day Adventist, the father of modern young-earth “scientific creationism.” He was a high school graduate with very little college exposure, often sold books door to door, was very poor, did some teaching. He was convinced that scripture was a divine recording of natural science, that Genesis recorded facts of Earth’s natural history. That was the bottom line.

As a Seventh-day Adventist, he accepted the authority of SDA founder Ellen White’s vision of creation that confirmed aspects of creation. So, he knew from his religious beliefs how the earth was created, and so on. Price realized that he could kill two birds with one stone. He resurrects a 19th century proposal called “flood geology”[36] which said that scripture, as a divinely revealed history of the earth, should control scientific interpretations of geology, biology and other things. The fossils and geographic features found all over the world, the mountains, the valleys, everything, were all caused, in Price’s view, by the global flood of the Bible. Therefore, the earth was young, because all of this stuff that geologists used to show an old earth that was actually due to the Flood and the Bible tells us that was recent, around 3000 BCE. Therefore there was not sufficient time for evolution to operate. He’s both defended the young-earth position of the Bible— the true interpretation, in his view— and slain evolution. And so the Bible is true after all.

Price published this kind of argument in dozens of publications, but when they’re reviewed by geologists, the responses are uniformly negative. It’s very amateur, it’s incoherent, it is not scientific geology but theological and fundamentalist geology, as one critic says.[37]

At the 1925 Scopes Trial, Price is one of two “scientists” cited by William Jennings Bryan in defense of the Bible;[38] He gets some publicity that way. Fast forward to 1961. Henry Morris and John Whitcomb are a theologian, and a hydrological engineer. They are both young earth creationists, very aware of Price’s work, and they decide to adapt and update his material into a book called The Genesis Flood.

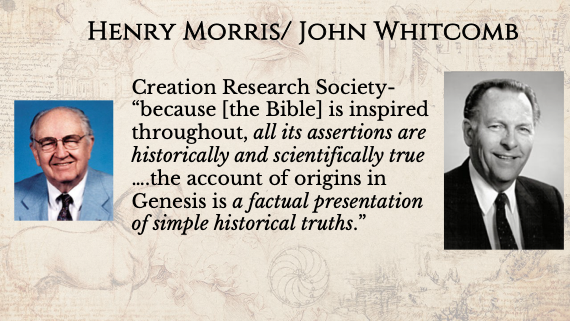

Now they strip out as much of Price and Seventh-day Adventism as they can, you know, you don’t want Ellen White’s vision in there because scientists aren’t going to buy into that, non-Seventh-day Adventists aren’t going to buy into that.[39] And they float it to some very conservative Protestant publishers like Moody Press, and get rejected. They end up with a very small publisher. And to everyone’s surprise, The Genesis Flood sells like hotcakes. It sells thousands and thousands of copies, and gets translated into other languages and sent all over the world. And these two go on to found the Creation Research Society, which is still around. Now, “hermeneutics”! What are their assumptions?

- The Bible is inspired throughout, so

- All its assertions are historically and scientifically true.

- The account of origins in Genesis is a factual presentation of simple historical truths. Well, no need for Hebrew, no need for Ancient Near Eastern context.

- You just read it as it is, at face value.

- And the scientific facts are clearly there unless you’re an intellectual trying to get away from the obvious truths of the Bible.

These are the hermeneutical assumptions they are following. American “scriptural geology” or “flood geology”— which Price had resurrected from the 19th century and brought into the 20th century and then popularized by Whitcomb and Morris in 1961— was

less about geology than about scripture and less about the content of Scripture than about its interpretation. In the end, scriptural geology and its more modern version of flood geology were and are really symbols of a different question. How is the Bible to be interpreted and how is information from outside the Bible to be considered and incorporated, if at all, into the interpretation of Scripture. In short, scriptural geology was not about geology, it was all about hermeneutics.[40]

Where are Latter-day Saints in this history? Back to 1925. We’ve got the eclipse of Darwin happening, the early beginnings of the modern synthesis with Darwin and Mendelian inheritance. We’re coming to the end of the fundamentalist/modernist controversy, when fundamentalism goes underground. We’ve got the Scopes trial with evolution and William Jennings Bryan. Now it’s not well known that Brian actually believed in an old earth, and was fine with evolution of plants and animals humans excluded, they don’t tell you that in Inherit the Wind; Bryan is just kind of the idiot fundamentalist par excellence.

Latter-day Saints had deep sympathies with fundamentalism. Given a cultural binary with, seemingly, Jesus and science and scripture on one side, and “atheistic evolution” and “destructive biblical scholarship” on the other side, Latter-day Saints— including much of church leadership— did not find that to be a difficult alignment to make. There was a strong connection with William Jennings Bryan; he had spoken in the Tabernacle, he knew several Apostles, President Grant loved his books, he distributed them by the hundreds to missionaries, he marked them up in his library. The Desert News enthusiastically printed Bryan’s sermons. In 1925, right after the Scopes Trial, we also get a “revision” of the 1909 First Presidency statement on the Origin of Man. It gets shortened considerably, with a lot of what is perceived as the strongest anti-evolution language taken out.[41] It’s republished with new First Presidency signatures as “a ‘Mormon’ view on evolution.” And it’s sent to non-LDS newspapers and also published in the Desert News. It’s considerably less anti evolution than the 1909 version.

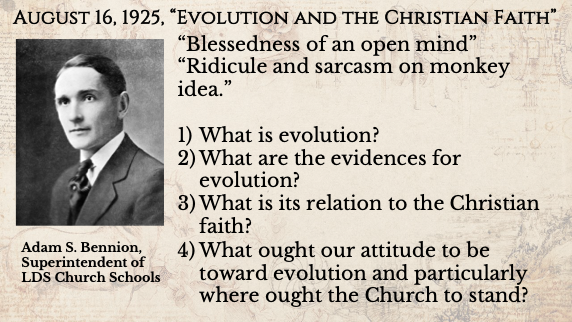

Now on evolution itself, there are mixed takes among church leadership from thundering rejection to cautious acceptance. Let’s start with the cautious acceptance. Adam S. Bennion was the superintendent of LDS Church schools, I think he was roughly the equivalent of today’s Church Commissioner of Education. In 1925, he gave a talk called “Evolution and the Christian faith” at a CES training meeting. This is all professional seminary and Institute teachers employed by the Church and this is the talk he gives. He speaks of the blessedness of an open mind. He condemns the ridicule and sarcasm of the “monkey idea,” that is, people who are dismissing evolution because “we didn’t come from monkeys.” And he covers four areas, 1) What is evolution? 2)What are the evidences for evolution? And here he had read some technical works, which is interesting because he was not trained in science. 3) What is the relation between evolution and the Christian faith and 4) what ought our attitude to be toward evolution and particularly where out the Church to stand?

Now, I think if the Church had some kind of secret official position that evolution was completely beyond the pale, unacceptable, the superintendent of LDS Church schools would certainly not teach all the seminary and Institute teachers the exact opposite. Another talk in 1925 that he gave— I have not been able to figure out his venue or audience for this— But he says,

we talk about evolution, a good bit is forced upon all thinking men and women these days. President Ivin’s [that is in the First Presidency from General Conference] says in the face of evolution to seek truth and find it, I beg of you, older men and women be similarly charitable, because you may have been given a prejudice in your youth, do not feel to ask this institution in the light of all recent learning to close its doors to honest investigation.

Now President Ivins had spoken in General Conference, and the gist of his talk was, look, whatever evolution happened, God was involved. That’s all I’m saying. That’s it. He was open to it as long as it didn’t kick God out. Bennion would be called as an Apostle in 1953, replacing John Widtsoe. That’s a strange calling, IF he had used his position over CES to encourage openness to evolution AND the Church had a strong official position against it.

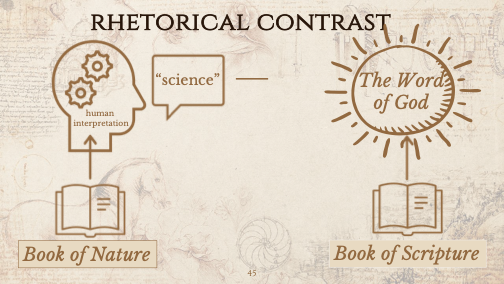

Now, on the thunderous rejection side, Joseph Fielding Smith. What were Smith’s hermeneutical assumptions and what did he feel was at stake? Smith thought there was a stark contrast between science and the Word of God. That is, while science involved human interpretation, scripture did not.

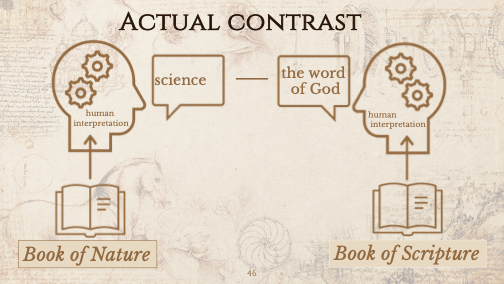

In actuality, human interpretation is involved both in looking at the rocks on the ground, the measurements we make, as well as the data, if I can call it that, in Scripture. We all have to interpret both of those things. There is human interpretation involved in both. It is not this one-sided thing where we distrust science because humans are involved, but, supposedly, “we can trust scripture because it’s purely divine and its meaning self-evident and needing no interpretation.”

That was one of his keys, his hermeneutical assumptions. Now what was at stake for Smith? It’s important to understand this because I think otherwise we mischaracterize him, we might feel negatively towards him. Smith thought everything was at stake with this issue;

- About the temple. “It surely is a deception if there were other races proceeding Adam, if this Genesis story is not true, then there can be little real purpose in these ordinances in the temple. There are a futile, meaningless, and not worthy of the place we give them.”

- He thought the revelations were at stake “if I am wrong, then the revelations are wrong.”

- “If evolution is true, the church is false. You cannot believe in this theory of the origin of man and at the same time except the plan of salvation, you must choose the one and reject the other.”

- And lastly, in 1937, “we may just as well close up our shop and say to the world that Mormonism is a failure.”

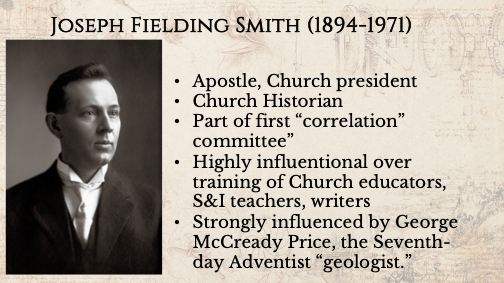

So for Smith, everything rode on this, that is why he fought against it so hard. And that position that he took stemmed from his interpretations and his assumptions, his hermeneutics. Now, a little bit of biographical background. Smith of course, was an Apostle, eventually a Church President. He was Church Historian for decades. He was part of the first “correlation committee” back in the 1940s, that was looking at things that got printed and saying, “yes, this is okay. No, that’s not you need to change this.” He was also highly influential over generations of church educators, Seminary/Institute teachers, writers and other general authorities. Now, what many of you may not know is he was also strongly influenced by George McCready price, the Seventh Day-Adventist “geologist.”

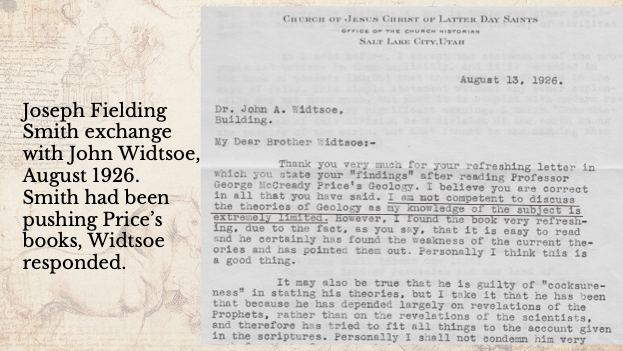

As early as 1926, Smith is reading Price’s books and suggesting them to his fellow Apostles. And we have letters back and forth between him and Widtsoe where Widtsoe criticizes them and Smith pushes back. Price, says Smith, can be “cocksure,” because he’s relying on the scriptures instead of the human “guesses” of the geologists. So Smith sees in Price someone with similar assumptions, a similar commitment to the Bible, and Smith is reading them and recommending them to people.

Note my little underlined phrase here, “I am not competent to discuss the theories of geology as my knowledge of the subject is extremely limited.” Five years later in the controversy with BH Roberts book, Smith writes a 56-page rebuttal to Roberts, about the age of the earth, pre-Adamites, and death before the fall. He dedicates nine pages to the “Fatal Mistakes of the Geologists.” And he relies entirely on Price! So contrary to 1926, Smith has now come to feel he does understand geology, and his informant is George McCready Price.

James E. Talmage held a PhD in geology, his son Stirling was also a PhD geologist, and Talmage is active in this discussion. And Smith actually writes to Price several times trying to get ammunition against Talmage’s arguments around this time. So they exchanged letters. Smith later joins Price’s flood geology research group, he gets their newsletter called The Creationist.[42]

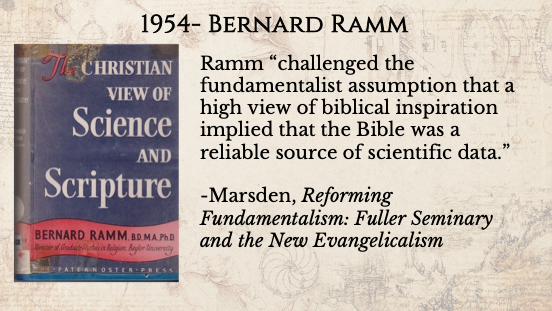

I want to jump ahead to the 1950s because that’s where some major things happen. That again, is where things about DNA were discovered that really cement evolution to a great extent. There are some major things with Protestants and Latter-day Saints. Let’s start with Protestants. Among Protestants, there is a landmark book published by Baptist scholar named Bernard Ramm, The Christian View of Science and Scripture. Ramm “challenged the fundamentalist hermeneutical assumption that a high view of biblical inspiration implied that the Bible was a reliable source of scientific data.”

In other words, Genesis could be absolutely true, even inerrant, but that did not mean that it was recounting natural history, or that it was scientific in nature. And Ramm generated a lot of responses which I won’t go into. Ramm is also the guy who coined the term or perhaps just popularized it, Concordism, which I talk about a lot. “Concordism” is the hermeneutical assumption that scripture is speaking in scientific terms, and therefore to be true and inspired, it has to match what science says. That’s concordism. Now, every single book and paper I have read from an LDS person from the 1800s to the present assumes Concordism when trying to talk about creation or evolution or reconcile science and scripture. It is a pervasive assumption in Latter-day Saints thought and it’s not a justified one. Ramm’s book opened up the door to Protestant scholars for interpreting the Bible in its ancient Near Eastern context.

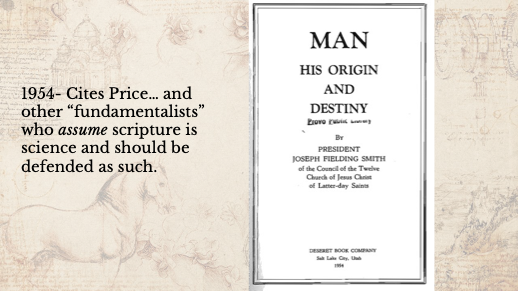

Well, in 1954, we also get Man, His Origin and Destiny, which pushes Latter-day Saints in the other direction from Ramm and those Protestants. Smith quotes Price and others who made similar assumptions.

It gets a big push at the 1954 BYU summer school for all Seminary and Institute teachers employed by the Church, with Elder Harold B. Lee as the primary teacher. His topic is “fundamental concepts and teachings of the church,” and he assigns Man, His Origin and Destiny as the textbook, and requires everyone to write a paper on it. He gives several talks related topics on Genesis, like the flood and creation. He touts Smith’s sources, such as Byron C. Nelson, as a “scientist.” (Nelson was actually a Lutheran pastor who drew heavily on Price.) Lee also quoted Price as “Dr. George McCready Price, eminent in his field, whom the geologists recognized as one of their standing.” Well, none of that was true even when Price began writing books back in the 1900s. I don’t know where Elder Lee got his descriptions of these guys, but he was misinformed about his qualifications and relative status among geologists.

But think about the effect this has on an entire generation of Seminary and Institute teachers! Here they have the two senior Apostles[43]— Elder Joseph Fielding Smith was invited to lecture as well— recommending fundamentalist sources and concordist interpretations of Genesis as acceptable orthodox sources, which had scientific respectability and personal apostolic approval.[44] Elder Smith spoke twice, invited because they were reading his book. When asked about his view of the age of the earth, Smith said he was not interpreting scripture he was merely “relating the facts as the Lord revealed them.” And if any of the teachers disagreed, “you have no business in the church school system.” There was a line of orthodoxy drawn around these young-earth concordist interpretations of scripture, a line not necessarily shared by other Church leaders.[45] Several of these teachers actually did seek private meetings with Elder Smith and President McKay, and decided to retire.

Leonard Arrington, the Church historian (1972-82), noted that “there emerged at BYU in the 1950s and has continued among some people there particularly in the religion [department], a sort of Mormon fundamentalism like Protestant fundamentalism, which emphasizes biblical literalism[,] rejects higher criticism and Biblical Studies, and the law of evolution.”[46]

Again, note the linking of fundamentalism with particular kinds of scriptural interpretation and attitudes to evolution. Now from this point in 1954, we get a string of books by Elder Smith and people who reflect his hermeneutical assumptions. These are published by Deseret Book, and perceived as authoritative and orthodox.

This fundamentalist trend culminates in the 1980 Old Testament Institute manual, which has a 2000 word quotation from a Seventh-day Adventist pamphlet called “Creation, the Evidence from Science.” There are referrals in the text to fundamentalist and catastrophist literature which are recommended; it pushes a young earth, it quotes Joseph fielding Smith in forcing a choice between the gospel and evolution. This remains the current Old Testament Institute manual, translated into dozens of languages. (I provide more details about it here.)

If you are a new convert in Japan, or Brazil or Russia, this manual remains the most detailed, most official, most accessible publication you have on “what does the church teach about Genesis and evolution?” And that is what you find. Now, this went manual up before Correlation, and they approved it with no pushback, with one exception. They inserted an old earth option, from Henry Eyring, into the discussion of age of the earth. That was it. And this, by the way, made the writers furious because it was so obviously “not doctrinal.”

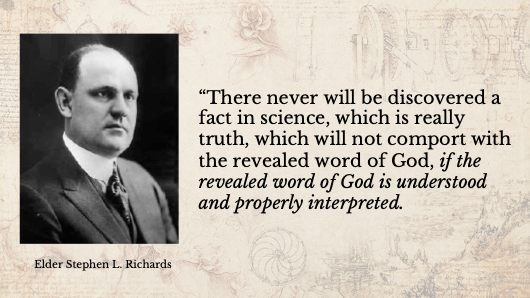

Now, I want to take a different tack as I conclude this history. I’m going to quote elder Stephen L. Richards.

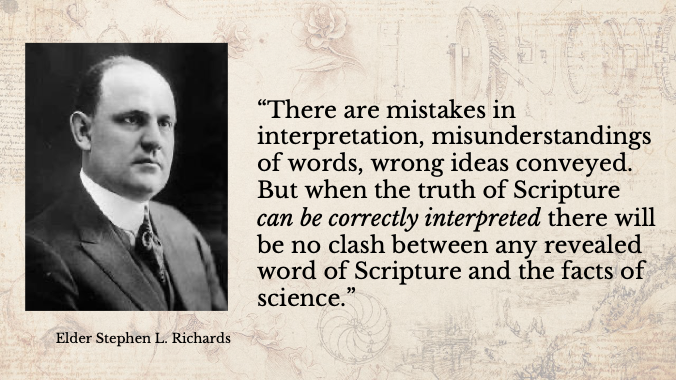

“There never will be discovered a fact in science which is really truth which will not comport with the revealed Word of God if the revealed Word of God is understood and properly interpreted. [Hermeneutics!] There are mistakes in interpretation, misunderstandings of words, wrong ideas conveyed. But when the truth of Scripture can be correctly interpreted, there will be no clash between any revealed word of Scripture and the facts of science.”

How do we interpret?

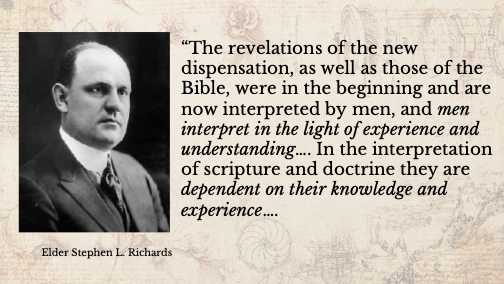

“The revelations of the new dispensation as well as those of the Bible were in the beginning and are now interpreted by men and men interpret in light of experience and understanding,” and it’s clear, if you read between the historical lines, he’s talking about church leadership.

“In the interpretation of Scripture and doctrine, they are dependent on their knowledge and experience. Old conceptions and traditional interpretations must be influenced by newly discovered evidence, not that ultimate fact and law change. But our understanding varies with our education and experience.”

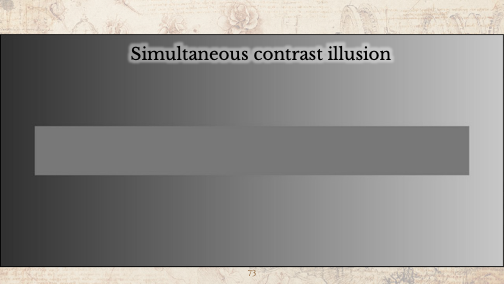

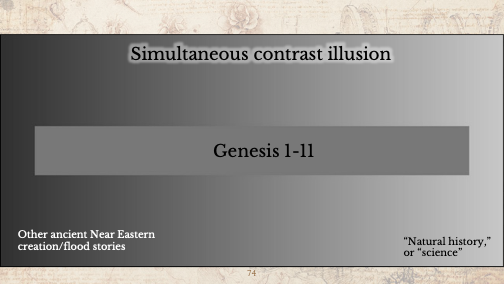

Now, this is called the simultaneous contrast illusion, that bar in the middle is the same color all the way across the screen. But it looks different depending on what you’re comparing it to. If we compare Genesis to natural history or science, because we have concordist hermeneutical assumptions, we think that’s what it needs to be compared to, that’s the kind of thing it is, you end up either a young earth creationist (forcing the science to fit into a face-value reading of Genesis), or end up reading modern science and scientific concerns into Genesis; that is when it’s talking about the firmament, Genesis is somehow talking about clouds or an ice canopy. And when it says there is matter unorganized, that’s perhaps talking about the Oort cloud. But these things were not in the mind of the authors of Genesis. That was not the audience, or the genre, or the spiritual needs they were speaking to.

If on the other hand, you compare Genesis to other ancient Near Eastern creation and flood stories on the left side, Genesis looks very, very different. It makes a lot more sense and there’s much less conflict. This essentially establishes that comparing Genesis with science is comparing apples and oranges. It’s not a legitimate comparison to begin with, because it’s based on unjustified and anachronistic concordist assumptions, bad hermeneutics.

And finally, a short personal note. When my wife and I were engaged at BYU, I was a Near Eastern Studies and pre-med major and she was molecular biology with a chemistry emphasis.

And our biggest argument—the only one we both remember— was about evolution, because I had become anti-evolution on my mission. I had foolishly traded a Hugh Nibley volume for a book called Combating Organic Evolution with the Book of Mormon, which was garbage. And our discussion helped me understand that maybe I was wrong about what I thought about the science of evolution. Science, however, could not replace the simplistic story I read out of Genesis; it seemed obvious at face value that evolution was not compatible with what Genesis said. Science couldn’t give me that. I didn’t get that yet. But it did convince me I was wrong about the scientific strengths of evolution.

Well, off I went to six years of school at the University of Chicago doing Hebrew and Aramaic and Assyrian and Babylonian. And I quickly realized that my assumptions were not just slightly off, but not even in the ballpark. And that really helped open my mind to evolution because I realized I had been approaching scripture very, very wrong, with uncalibrated assumptions. Once I was embedded deeply and reading scripture in context, my approach changed. It changed what I saw the options were and my opposition disappeared.[47] I affirm that scripture, and Genesis, in particular are true, but I reject the fundamentalist assumptions that scripture is the simple recording of divinely revealed or dictated facts, that context is practically unnecessary, and that scripture requires no interpretation. I wish we read scripture more and pay closer attention to it. At the end of the day, I am deeply a believer, but not a fundamentalist.[48] Thank you.

Q&A

Scott: Thank you, I think it’s a really interesting conversation. I think most people don’t come to don’t expect to come to a religious conference and talk about evolution. I think you’ll find that if you did it with Seventh Day Adventist or—

Ben: I suspect some people have come here for exactly that, actually.

Scott: Okay, well, that’s good. Here are some of the questions we received, “you say that the motivation for fundamentalists to resist evolutionary theory is to be faithful to Scripture. But don’t you think there are other motivations as well, such as feeling the need to resist secular science, or concern with the tendency of atheism to latch on to evolution as a way of accounting for the universe while excluding the notion of God?”

Ben: Yeah, that’s certainly there in the history. But that’s secondary. And there is a difference between the science of evolution and the secondary and tertiary philosophical interpretations of evolution that get put out by atheists who want to use the science narrowly, as a club to beat religion over the head. And that is definitely something that people respond to. But in my reading, I’ve read many published stories of how conservative evangelicals have come to embrace evolution.[49] And almost all of them mentioned something about, “I encountered something like Bernard Ramm’s book[50] that helped me see that I was interpreting scripture wrongly with these assumptions that I didn’t even know I had.” So those aspects are certainly there in the history, but they’re not the primary motivator.

Scott: Makes sense. And I have two questions on Adam and Eve.

Ben: Well this will be quick.

Scott: What’s your best idea of how Adam and Eve got here? Are you including in the special creation idea that Adam and Eve were born of heavenly parents or natural body processes? Would you consider that idea to be a third distinct category from sexual creation evolution?

Ben: Let’s see. So, there are a variety of opinions expressed boldly by Apostles in church history on Adam and Eve. Joseph Fielding Smith is adamant that their spirits came from elsewhere, but their bodies came from here. He does not expand on that much. What was the first part?

Scott: What’s your best idea for how they got here?

Ben: I am non-committal. I will say that if you read in this literature, there are a number of options presented by believing scholars from a variety of other religions. One of them that’s recent is actually transplantation, according to which, there was human evolution and at some point, God brings (or creates) Adam and Eve here and just works them into the mix. Another very popular one that I find somewhat attractive— but none of these are without their problems— is the idea that there was evolution and at some point, humans evolve enough or humanoids— I’m not a scientist, I don’t know that terminology— there is evolution to the point where God essentially picks a couple and says, I can make a covenant with you. You are Adam and Eve— Adam and Eve by the way, they’re generic names, they mean Human and Life, respectively.[51] They’re meant to be symbolic and encompassing. Now, that idea, David O McKay actually hinted at strongly in General Conference while he was President of the Church,[52] he seems to have maybe embraced that, although I’m reading between the lines a little bit. He became significantly open to evolution during his tenure as Church President.[53] So you’ve got special creation, you’ve got evolution and transplantation, you’ve got evolution, and then kind of a covenant couple. There are a couple other options. I’m not terribly concerned. I mean, my main motive in doing this… I am not an evolution apologist.[54] I actually don’t care (much) about the science; I am mostly interested in helping people who find their testimony challenged by evolution, and Church history, and what scripture says. [Ben adds, I’m interested in tracing where our ideas came from, and as is clear, certain interpretations of the scriptures which became very mainstream and orthodox were heavily influenced by Seventh-day Adventist and fundamentalist interpretations and assumptions.]

Scott: My father who’s a biologist liked quoting, and I’m not even sure who he quoted, but his quote was, “Adam and Eve were the first people who spoke with God.”

So, we have one person objecting to your asking about your data about evolution, beliefs among students at BYU. He said, “many of my fellow students took Dr. Jeffries, very popular and influential zoology class that examined evolution in detail and accepted many of the truths of evolution.”

Ben: Jeffery came to BYU in 1970, dedicated evolution classes just started being taught in ‘71 or 72. They were verbally approved by President Joseph Fielding Smith, by the way, which is counter-intuitive. Those statistics above come from 1973. But evolution at BYU post-1970s and 80s is quite different than prior to that time, I would say. And I have other data on that. Jeffery is great. I’ve been in his archive a lot and interviewed him.

Scott: Have you ever heard a story where Roberts or talmage found fossils and rocks from in and around Adam on diamond and laid them on the president Smith’s desk?

Ben: I think that’s getting some of the details wrong. That’s actually from James E. Talmage’s journal letter to his geologist son Sterling,[55] where he went to the supposed altar at Adam-Ondi-Ahman in Missouri, examined it, found fossils in those rocks and said, Well, here’s proof that there was death before the fall. Because otherwise there wouldn’t be fossils in there. I don’t know how serious he was about that. But it was kind of a conundrum for Joseph fielding Smith, I imagine.

Scott: How do we defend evolution to LDS convinced fundamentalists?

Ben: You know, there’s been a lot of literature in the last four years about, how do you argue with people who are holding untenable positions. And the literature is all over the place. Some of it says “you can’t, so don’t bother.” Some of it says, “Don’t argue directly, just ask them questions and help draw out their assumptions until they realize. Some of it jokingly suggested, “Well, if someone comes to you and says, I think the moon landing was a hoax,” one-up them and say “you believe in the moon?! come on, what’s wrong with you?!” I don’t think that was entirely serious. But sometimes, if you can help someone, perhaps, realize that their position is very much an outlier if they think it’s mainstream. I mean, one of the things that I tried to highlight in this talk was, many people have the idea that there was kind of this so-called “literal” interpretation of Genesis and everyone believed in a young earth until Darwin came along. And it’s really surprising to learn that virtually all Christians in America, I mean, I’m paraphrasing, but the default view was an old earth from the 1800s,[56] at least onwards, Darwin didn’t have anything to do with that. That’s very counterintuitive. So if you can, you can show people you know, that idea came from a specific place and time and it was very strange. And this other view has been around for a long time. Now, those Catholic priests in the 13th century who were saying, “When God creates in Genesis 1:1 all he creates is matter with potential built into it. And everything after that is the naturalistic unfolding of that potential that God imbued it with.” That is fascinating. Nobody knows about it! And here you have kind of quasi-evolutionists, who were, you know, pre-scientific-revolution, not responding to Darwin, nothing like that. It’s fascinating to me!

Scott: So, excellent. So, I want to thank you for your time, both your time speaking to us here and your time you’ve donated to FAIR and helped us much thank you so much. Thank you.

[1] https://archive.org/details/conferencereport1932a/page/n123/mode/2up?q=fundamentalists

[2] Since giving this presentation, I came across some new information in an archive. I cannot confirm this information, but it would at least partially explain the extremity of this shift. BYU zoology professor Duane Jeffrey writes to LDS geologist William Lee Stokes in 1990, “I view [these] data with horror. But it is only fair to point out that the original Harold Christensen data, from the 30s, encompassed the entire BYU student body. These latter data came from only a small subset— three classes, as I recall being told by Harold— and two of them were taught by George Pace…. He is deliberately chosen by a [group] of students who like his stuff; the sample is therefore probably not representative of the student body as a whole. This should not be taken as implying that I think the problem is not real, however! It is real!” Other statistical polling (e.g. Pew Research) generally demonstrates Latter-day Saint rejection of evolution, although it also appears to depend upon the phrasing of the questions.

[3] This openness began with the 1950 encyclical Humani generis; John Paul II cited Humani before stating “there is no conflict between evolution and the doctrine of the faith regarding man and his vocation, provided that we do not lose sight of certain fixed points. … Today, more than a half-century after the appearance of that encyclical, some new findings lead us toward the recognition of evolution as more than a hypothesis.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution_and_the_Catholic_Church#Popes_Leo_XIII_and_Pius_X

[4] Because Lewis is a cherished figure to Christians across the gamut, a number of “camps” try to claim him for their “side.” Note this brief excerpt from his 1940 The Problem of Pain, “For long centuries God perfected the animal form which was to become the vehicle of humanity and the image of Himself …The creature may have existed for ages in this state before it became man.” Note also this review of a book in Sehnsucht: The C.S. Lewis Journal which claims Lewis became anti-evolution late in life. Suffice to say, Lewis rejected biblical inerrancy, a young-earth, and other standard aspects of modern creationism.

[5] Graham, like a number of other Christians, saw divinely-guided evolution as acceptable. “I believe that God created man, and whether it came by an evolutionary process and at a certain point He took this person or being and made him a living soul or not, does not change the fact that God did create man.” In “Doubt and Certainties” (1964) Graham opposed evolution to the extent that it was used to rule out the existence of God.

[7] E.g. John Walton, who must sign a statement of faith affirming inerrancy every year as part of his contract at Wheaton.

[8] As quoted in Ronald Numbers, The Creationists (2006), 60.

[9] “In short, then, the hard core of young-earth creationists represents at most one in ten Americans—maybe about 31 million people—with another quarter favoring creationism but not necessarily committed to a young earth.” https://ncse.ngo/just-how-many-young-earth-creationists-are-there-us

[10] See my 2017 FAIR talk, https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august-2017/truth-scripture-and-interpretation But see also more recently these posts about premises in science and religion. https://benspackman.com/2021/11/are-not-these-conclusions-reasonable-premises-faith-and-argument/

https://benspackman.com/2021/11/premises-genesis-and-the-priesthood-ban-and-creation/

[11] On the nature of science, see popularly, Grandy, David A. and Bickmore, Barry R. “Science as Storytelling,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53:4 (2014). A technical version was published as “Science As Storytelling for Teaching the Nature of Science and the Science-Religion Interface” Journal of Geoscience Education, 57:3 (June, 2009). See also, Richard DeWitt, Worldviews: An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Science (Wiley Blackwell, 2010)

[12] “The debate has tended to take place on scientific grounds, focusing on the interpretation of scientific data and theories rather than the interpretation of scripture.” Mark Harris, The Nature of Creation: Examining the Bible and Science (Routledge, 2014), 2.

[13] There are some young-earth creationists who hold that God only created different basic “types” and which then diverged into varieties; some hold that this happened very quickly after Noah’s flood.

[14] See, popularly, Rebecca Stott, Darwin’s Ghosts: The Secret History of Evolution (Random House, 2013)

[15] See James Secord, Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (University of Chicago Press, 2003). C.f. Bowler, Evolution: The History of An Idea, 25th Anniversary Edition (University of California Press, 2009), 134ff.

[16] Bowler, chapter 7, “The Eclipse of Darwinism”

[17] These included things like 1) age of the earth, which Lord Kelvin calculated at only 100 million years, not enough time for evolution to occur as Darwin proposed it, and 2) little understanding of heredity or its mechanism. Many thought traits were simply blended in offspring. The discovery of radiation (which Kelvin could not account for in his calculations) and Gregor Mendel’s work on inheritance and heredity eventually undercut these objections.

[18] Sydney Ross, “SCIENTIST: THE STORY OF A WORD,” Annals of Science 18:2 (June 1962), 65-86.

[19] Theodore M. Porter, “How Science Became Technical” in Isis 100 (2009):292–309

[20] Numbers, “Science Without God: Natural Laws and Christian Beliefs,” in When Science and Christianity Meet. “No single event marks the transition from godly natural philosophy to naturalistic modern science, but sometime between roughly the mid–eighteenth and mid–nineteenth centuries students of nature in one discipline after another reached the conclusion that, regardless of one’s personal beliefs, supernatural explanations had no place in the practice of science…. [Virtually all scientists] whether Christians or non-Christians, came by the latter nineteenth century to agree that God talk lay beyond the boundaries of science.” 272. This is the “methodological naturalism” of science.

[21] Notably, those 13th century Catholic theologians above would likely have cast a disdainful eye on explaining creation with a simplistic “God did it, and that’s all!”

[22] This is the idea of “primary vs. secondary causation,” and this kind of thinking had been around for hundreds of years. God was the primary cause of everything; the question was, what were the secondary causes— God’s laws— by which nature was governed? Talmage discussed primary and secondary causation in his 1931 “Earth and Man.”

[23] Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 15. C.f. Bozeman, Protestants in an Age of Science: The Baconian Ideal and Antebellum American Religious Thought (University of North Carolina Press, 1977)

[24] Anti-evolutionists “insiste[d] on the factual, non-theoretical nature of science, harmoniz[ing] with the once-venerated teachings of the English philosopher Francis Bacon, whose name in America had symbolized correct scientific method. By narrowly drawing the boundaries of science and emphasizing its empirical nature, creationists could at the same time label evolution as false science, claim equality with scientific authorities in comprehending facts, and deny the charge of being antiscience.” Numbers, Creationists, 65.

[25] It remains the case, unfortunately.

[26] See Mark Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (University of North Carolina Press, 2006)

[27] See Marsden, but also Longfield, The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates (Oxford University Press, 1991)

[28] Grant was not the only Church leader to align with Fundamentalism in public settings and missionaries also aligned Latter-day Saints with fundamentalism when asked.

[29] Some Church leaders have embraced a form of de facto inerrancy. For example, Joseph Fielding Smith believed that “men are infallible… when they, as prophets, reveal to us the word of the Lord.” See Steven H. Heath “Agreeing to Disagree: Henry Eyring and Joseph Fielding Smith” in The Search for Harmony, available at http://signaturebookslibrary.org/agreeing-to-disagree-henry-eyring-and-joseph-fielding-smith/

[30] Most Christians read Genesis either through the lens of the “day-age theory“ (as did many Latter-day Saints) or “gap theory” (as did some Latter-day Saints.)

[31] Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 212-4. Cf. footnote 22 above with the quote from Numbers.

[32] See Edward Larson’s Pulitzer-winning Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion (Basic Books, 1997)

[33] One author writes of “Inherit the Wind” that while it “remains faithful to the broad outlines of the historical events it portrays, it flagrantly distorts the details, and neither the fictionalized names nor the cover of artistic license can excuse what amounts to an ideologically motivated hoax.” Carol Iannone in First Things, https://www.firstthings.com/article/1997/02/002-the-truth-about-inherit-the-wind–36

C.f. Edward J. Larson, “The Scopes Trial in History and Legend” in Lindberg and Numbers, eds. When Science and Christianity Meet (University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[34] Operating from memory, I orally overstated the extent of this, presenting the traditional “prevailing story,” reflected in a number of works. However, it has been strongly questioned recently by some historians. “Regardless of how the concept is measured, evolution never really disappeared from biology textbooks….Ronald P. Ladoucer has argued that this narrative is largely a ‘myth, created first as part of a public relations effort by the Biological Science Curriculum Study (BSCS) to differentiate, defend, and promote its work, and later as part of an attempt by scholars to sound a warning concerning the rise of the religious right.’” Shapiro, Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 160. For a summary, see https://daily.jstor.org/the-hidden-history-of-biology-textbooks/

[35] This is the traditional view. For an alternativee, see Matthew Avery Sutton, American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (Harvard University Press, 2014)

[36] See Numbers, The Creationists; James R. Moore, “Geologists and Interpreters of Genesis in the Nineteenth Century,” in Lindberg and Numbers, eds., God and Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter between Christianity and Science (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 322–50; Martin Rudwick, “The Shape and Meaning of Earth History,” ibid., 296–321; Stiling, “Scriptural Geology in America,” in Livingstone, Hart, and Noll, eds. Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective (Oxford University Press, 1999)

[37] “Your geology is theological rather than scientific.” Malcolm H. Bissell (Geology, Bryn Mawr) to George McReady Price, Jan 5, 1923. Scan in my possession from the Price papers at Andrews University.

[38] This is in the transcripts of day seven of the trial, under the heading “How Old is the Earth?” The other named in the trial was George Frederick Wright, at Oberlin. See Ronald Numbers, “George Frederick Wright: From Christian Darwinist to Fundamentalist” in Isis 79:4 (December 1988), 624-45.

[39] The evidence of plagiarism here is quite extensive. Based on letters they exchanged with Price, however, it seems he was fully aware of their work and encouraged it.

[40] Stiling, “Scriptural Geology in America,” 188.

[41] See https://benspackman.com/2021/02/the-1909-first-presidency-statement-in-its-historical-context/

[42] These details are based on my dissertation research. For further context, see https://benspackman.com/2020/11/tales3/. I anticipate some publications in the future that provide more details on this.

[43] Although Lee was only called to the Quorum in 1941, due to several deaths and the excommunication of Elder Richard R. Lyman, by 1954 Lee was second in seniority behind Joseph Fielding Smith, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve.

[44] Notably, Man, His Origin and Destiny made little reference to the views of any other LDS apostles who had relevant scientific training or held differing views. This was noticed by many LDS readers, who wrote letters to President McKay or other prominent Latter-day Saints about it. For example, LDS paleontologist Lee Stokes wrote to Henry Eyring Sr., “So far as I know, the complete lack of reference by President Smith to the writings of his fellow apostles is almost without parallel in Church literature. I do not believe the man who wrote “Jesus the Christ” and “The Articles of Faith” can be completely ignored in a field in which he was well-trained and proficient.” There is a deep irony in implicitly rejecting the teachings of earlier LDS General Authorities as “philosophies of men,” while touting fundamentalist creationists as respectable mainstream authorities and options for Latter-day Saints.

[45] In response, President McKay pushed J. Reuben Clark to give his famous talk, “When Are Church Leaders’ Words Entitled to Claim of Scripture?,” which has been published and cited in various places.

[46] Arrington journal, Dec 13, 1980.

[47] For a fuller telling of this story, see https://benspackman.com/2016/09/why-science-is-mostly-powerless-against-young-earth-creationism-a-personal-narrative/

[48] C.f. Tremper Longman III, “What I Mean by Historical-Grammatical Exegesis— Why I am Not a Literalist.” Grace Theological Journal 11.2 (1990), 137-155.

[49] See e.g. Applegate and Stump, eds. How I Changed My Mind About Evolution: Evangelicals Reflect on Faith and Science (IVP Academic, 2016).

[50] E.g. J. Richard Middleton’s Foreward to Matthew Hill, Embracing Evolution: How Understanding Science Can Strengthen Your Christian Life (IVP, 2020), x.

[51] See Ben Spackman, “‘Adam, where art thou?’ Onomastics, Etymology, and Translation in Genesis 2–3” in Adam S. Miller, ed. Fleeing the Garden: Reading Genesis 2-3 (Maxwell Institute, 2017.) Entire volume available at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=mi

[52] See my post at https://benspackman.com/2016/08/david-o-mckay-genesis-and-evolution-part-2/

[53] See my post above, the section on McKay and evolution in Prince, David O. McKay, and https://benspackman.com/2016/06/david-o-mckay-on-evolution-and-reading-genesis/

[54] See my post at https://benspackman.com/2021/02/what-im-doing-here-and-what-i-hope-others-will-do/

[55] Quoted in this article, http://signaturebookslibrary.org/the-b-h-robertsjoseph-fielding-smithjames-e-talmage-affair/

[56] See e.g. Numbers, The Creationists.