Let’s Talk About Polygamy

Brittany Chapman Nash

August 2021

Summary

Brittany Chapman Nash reflects on her personal journey from confusion and discomfort about Latter-day Saint polygamy to writing Let’s Talk About Polygamy. The concise book is aimed at helping others understand the historical, theological, and personal dimensions of the practice. Nash emphasizes that polygamy’s legacy is not monolithic. She encourages modern Latter-day Saints to approach the topic with empathy, humility, and a willingness to sit with unanswered questions.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Brittany Chapman Nash. Brittany is a specialist in Latter-day Saint women’s history. She co-edited the award-winning four-volume Women of Faith in the Latter Days Series. And she has done a number of amazing things that you can read in the program. But with just that short introduction, I’m going to turn the time over to Brittany Chapman Nash.

Presentation

Brittany Chapman Nash: As I sat in the front row of my seventh-grade U.S. history class in the eastern United States, my teacher began discussing the “polygamous Mormons in Utah.” My heart pounded. This was my moment to represent my faith as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

With nerves rushing, I raised my hand and timidly said, “Mormons don’t practice polygamy anymore.” My teacher acknowledged my assertion. That brief exchange was my first experience talking about the Latter-day Saint practice of polygamy.

I continued to have discussions about polygamy as I grew older. But I dreaded questions on the subject because I knew little about it myself. In my young mind, Latter-day Saints’ polygamous past was an embarrassment to reject, a point of misunderstanding to readily correct.

This experience from my life opens my recent book, Let’s Talk About Polygamy. To me, it encapsulates the anxious and awkward feelings I generally felt when trying to explain polygamy to others. The obligation I felt to defend it, even though I did not understand or feel comfortable with it myself. Perhaps you have been in that position as well.

My Book

Polygamy has since become a topic of deep interest and study for me, both in my career and personal research. When my firstborn child was three weeks old, Deseret Book invited me to write a short volume about a tiny topic: the practice of polygamy in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In my naïveté as a new parent, I thought, “In a couple of months, I will have this parenting thing down and I will be able to write a book. No problem.”

Three years and two children later, I am still trying to get this parenting thing down. But with a village of helpers who offered everything from childcare to endless draft reading, we managed to produce this book [holds up book]. It was released just over a week ago.

Speaking to you at FAIR so soon after its publication makes me feel as if things have come full circle. In 2015, I prepared a presentation about polygamy for the FAIRMormon conference. It was while preparing that speech that I first began articulating my own thoughts about polygamy.

Accessible Information

Deseret Book intentionally requested a short book so that the expansive topic of polygamy would be less intimidating to readers than a large, exhaustive volume. Page limitations to keep the book small compelled me to be as succinct as possible. This involved a difficult winnowing process as I tried to discern how to keep unwieldy topics concise and readable. What stories, quotations, and experiences to include.

The written portion of the book is 114 pages long. There’s an additional 22(ish) pages of notes and back matter to point readers to sources for more in-depth information on the many subjects I could dwell on only briefly.

I hope this book will help individuals understand the general history of Latter-day Saint polygamy. Learn reasons why it was practiced. Reconcile their own feelings about it. Become conversant enough on the topic to discuss it comfortably with people who are not Latter-day Saints. And, more importantly, to talk comfortably and openly about it amongst ourselves as Latter-day Saints.

I saw my role as an author on this topic not to defend polygamy as right or wrong. Or to try to make a messy topic neat and tidy. Rather, I endeavored to give insight into how and why, from nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints’ point of view, they chose to practice polygamy. I believe it is essential to let the Saints speak for themselves through their personal records. Letters, journals, and autobiographies. They knew polygamy best. They knew their reasoning best.

Contents of the Book, Let’s Talk About Polygamy

Now, rest assured, this presentation will not be a rehashing of the contents of Let’s Talk About Polygamy. But here is a quick glance at the Table of Contents.

As you can see, the book is divided into three basic sections:

The first section is devoted to the chronological history of polygamy. It starts with the organization of the Church in 1830 through to the present day.

The second section addresses more abstract questions of how the Saints practiced polygamy in their day-to-day lives. It also covers reasons and beliefs that motivated nineteenth-century Saints to practice polygamy. Again, I tried to stick closely to reasons they voiced. Their perspectives. I outlined general motivating trends based on their records.

Listen to the Saints’ Voices

Saints’ voices are used often throughout the first two sections. In the final section I wanted to give some breathing room for nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints to share their stories in greater detail. So after “talking about polygamy” for much of the book up to that point, I wanted us to be able to sit back and listen to the voices of Latter-day Saints telling us about their experiences. Their personal decision-making processes and family relationships within plural families. Then I sum up by giving my own thoughts about what polygamy means for Latter-day Saints in the modern day.

Being fresh out of writing Let’s Talk About Polygamy and thinking intensively about this charged and controversial topic, I pondered what I could offer from that experience that might be meaningful to you today. I would like to take you through the unexpected education I gained through writing about polygamy. I hope in sharing what I learned, you may think about polygamy a little differently.

First, I will discuss four points that I now view as common misconceptions of polygamy. Some of these persisted in my own mind as subconscious assumptions. I have observed them in countless others as well, while reading, conversing, or sifting through 180 years’ worth of people talking about polygamy.

Second, writing this book forced me to ask myself new questions that significantly influenced how I view plural marriage.

Lastly, I want to offer a reframing of how we can think about polygamy. And the questions we ask of it.

Common Misconception 1: All my questions about polygamy can be answered.

Fantasy: If I find just the right source (or scholar, or book, or website, or…) all of my questions about polygamy will be answered. Reality: Maybe, but probably not.

Learning broadly and deeply about plural marriage is essential and enriching. But a person very likely will never “arrive” at the satisfying state of having all questions about polygamy answered. Some questions simply do not yet have answers—due to lack of source material or lack of revelation.

Joseph Smith’s practice of polygamy and the doctrine he taught regarding it are two areas in which questions feel most pressing and definitive answers are most lacking. Not enough is known about Emma Smith’s experience of plural marriage. Or other important details pertaining to the early practice of polygamy prior to and in Nauvoo.

A major reason that knowledge is so slim about early Latter-day Saint polygamy in the 1830s and 1840s is because contemporary sources discussing it are quite rare. Contemporary sources, as opposed to later reminiscences, tend to be most reliable. There currently is not enough solid information to pin down an exact narrative of how things unfolded or why.

Not Knowing

I consciously chose not to record information about their involvement because they understood its highly controversial nature. They also held the practice as both secret and sacred. Much of what does exist is only fragmentary, or are later reminiscences or second- or third-hand sources. This makes it difficult to create reliable historical judgments about what was happening early on.

Because of this, many questions about this period cannot be answered satisfactorily. The gray space of not knowing is uncomfortable. But the reality is, definitive answers simply are not there for some questions.

The same is true for questions about the practice of polygamy in the afterlife. Some Latter-day Saints have soul-deep concerns about what the practice of polygamy will look like in the next life and how it may affect their happiness there. These questions are valid and important. Reflecting on the reality that not all questions about polygamy in the afterlife can be authoritatively answered right now is an important consideration.

These things being said, there are ways to feel some solidity in the midst of unknowns. Particularly as we reflect upon nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century plural marriage. There are pieces that can help put together the puzzle that is polygamy.

I started to think about those pieces in preparation for my 2015 FAIR presentation. After thinking more about plural marriage over the past few years, I would like to revisit those pieces. And add one more.

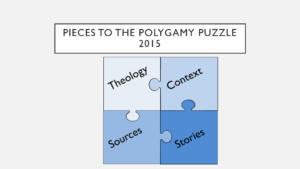

Pieces to the Polygamy Puzzle

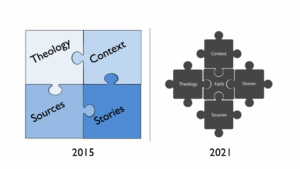

In 2015, I outlined four puzzle pieces that I believed—and continue to believe—are valuable building blocks for creating a well-rounded picture of plural marriage as it was practiced. I identified them as:

- Theology (the doctrines of the Church)

- Historical context (the external circumstances that affected the Saints’ opportunities and choices)

- Reliable sources (strong and accurate historical documentation)

- Experiences (individual stories of Latter-day Saints)

The combination of these puzzle pieces will not create a perfect or complete picture. But their union can provide a strong foundation to build further understanding upon.

I have since come to realize that I was missing a central piece of that puzzle: Faith.

- Faith

Realizing this was more of a “duh” moment than an “aha” moment. It was so present and central to the narrative that I failed to recognize and define it as something separate from the other pieces.

For the purposes of this book, I view faith as the spiritual conviction that influences individuals to believe in Latter-day Saint theology and act according to their understanding of that belief. Faith is the critical element that animates theology, brings light to historical context, gives depth to historical sources, and is the connecting thread that unites the stories of Latter-day Saints.

Common Misconception 2: We know all there is to know about polygamy

Fantasy: What we know about polygamy is complete. If I find out new information, and there is nothing else to learn, something is wrong.

Reality: Nineteenth-century Saints juggled different social and religious norms. Time and change have created a disconnect between our world and theirs. Sources continue to come forward that may shift narratives, or existing sources may be reinterpreted.

When I was a graduate student at the University of Leicester in Leicester, England, I studied the history and literature of the Victorian era. Part way through the program, I realized that I could have read all of the same books and studied all of the same information in the United States. But I would have completely missed the mark in my understanding. I would not have experienced the culture and physical spaces that produced the literature and history I was studying. Being in the places and part of the culture made all of the difference.

To me, studying history is like the different views in Google Maps. There is the aerial view, which gives you an idea of space, context, influences. An overarching narrative of what a subject or time period looked like, with all of its factual information.

Then there is the street view. I liken the street view to the stories and experiences of individuals as they, themselves, recorded them. Personal records help you get on the ground and feel and see through human eyes.

The Disconnect

BUT—the disconnect is that we can never actually be in those spaces. The vibe of the space, the smell in the air, the connections between people you pass on the street, the unspoken social norms. That is what we try to recapture by putting together puzzle pieces. But because we cannot be there, there will be pieces we can never quite understand.

Likewise, on some level, there will be a disconnect between their perspective and our perspective in the twenty-first century. The gender and family dynamics. Living conditions. Economic opportunities and priorities. Political and social pressures. Religious backgrounds and their role in society. Some of these things are not completely within our grasp.

Many things, of course, are within our grasp. We are equally human. We understand human emotions and have similar questions and concerns; but how we may process them is different. Why does that matter?

It teaches us that we do not and cannot comprehend everything about plural marriage. Setting that expectation is important. The nuances in sources and revelations matter deeply. There is room for interpretation—and even reinterpretation—of existing sources as time passes, knowledge increases, and accessibility to sources expands.

Example

As an example of this, I refer to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s recent book A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870. Because of her unique training as a historian and her creative combination of solely contemporary sources (she chose not to use later reminiscences, as most other historians do), she pieced together clues found in diaries, letters, textiles, a pictorial code found in Wilford Woodruff’s diaries, and other more unconventional sources to craft a raw and illuminating addition to the narrative of the development and evolution of plural marriage.

With that in mind, I made another change to the puzzle-piece graphic from 2015.

In that presentation, you will note that all four of the pieces fit together to create a complete, enclosed picture. I was not making any particular statement at the time by having the graphic enclosed. But it may have unintentionally sent the message that by exploring theology, sources, context, and stories, one could attain a whole and complete understanding of polygamy.

Room for Further Understanding

I have since come to understand the importance of not having the expectation that I can know and understand it all. There will always be more to the story. Nuances that limitations in my knowledge or my twenty-first-century glasses don’t allow me to see. The same is true for all of history, not just the history of polygamy. Not all stories are told or understood.

So, I have made room for more with this graphic in Let’s Talk About Polygamy. The puzzle is open and incomplete. There is always room for greater and deeper understanding. It is important to recognize that scholars have limitations. Sources have limitations. Our own understanding has limitations. Revelations have limitations. And not all of the information is there. There are going to be gaps. And people interpret those gaps differently. Expecting perfection is unrealistic.

Common Misconception 3: Men loved polygamy and women hated polygamy

Fantasy: Polygamy was all about sex; men love sex, therefore men loved polygamy. Polygamy was all about sharing; women hate sharing, therefore women hated polygamy.

Reality: Everyone had a different experience.

Polygamy is not one story. The spectrum of the Saints’ polygamous experiences varied widely based on the time period in which they practiced. Financial, social, and ecclesiastical status. A woman’s numerical wife position. Living arrangements. The husband’s presence in the home. Personality types. And myriad other influences.

Despite this, polygamy often all gets wrapped up as the same thing. At first glance, though, some assume that polygamy was all about sex. It was a widespread assumption in the nineteenth century and sometimes still is today. Plural marriage did provide men with more than one sexual partner. In fact, that was one reason Latter-day Saints promoted it.

Polygamy was touted as an antidote to adultery, fornication, illegitimacy, and even prostitution (big social problems at the time), because men had more than one woman with whom they could have divinely sanctioned sex with. Particularly during a wife’s pregnancy or lactation period, when married couples traditionally did not have intercourse.

Challenges

This mentality led President George Q. Cannon to say:

“Our crime has been: we married women instead of seducing them; we reared children instead of destroying them; we desired to exclude from the land prostitution, bastardy, and infanticide.”

—George Q. Cannon, A Review of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Case of Geo. Reynolds vs. The United States (1879)

I suggest that for most men, plural marriage was far from the sexual paradise and life of ease that steamy Victorian novels depicted it to be. Many men participated in it because they felt it was a religious duty. Indeed, Phineas Cook wrote that plural marriage marked the “beginning of all my sorrows.” Even though he was “converted to the doctrine of plurality.”

It was challenging to be the head of multiple households. Men often struggled to meet the complicated needs of their large families. In a letter to her aunt, Mary Jane Mount Tanner commented:

“I have told you men’s lives were not strewn with roses in these much married relations. If women was all they wanted they could buy or steal them as others did and save themselves so much trouble.”

A Matter of Religion

Travel writer Helen Hunt Jackson, who was not a Latter-day Saint, recorded a visit she had with a plural wife who confessed she hated polygamy. But despite the plural wife’s own challenges with the principle, “she believed that the Mormon men were sincere in regarding it as a matter of religion, and described them as good, earnest, true men who were faithful to their wives.”

At the same time, Mormon women readily admitted that some men and women did not enter polygamy with the purest motives. That not all men acted responsibly in their role of father and husband. “Men and women don’t always do right,” said plural wife Kristine Baird. “That has nothing to do with the principle.”

Elizabeth Graham Macdonald recorded:

“I have thought . . . that the actions of some were as much governed by passion as by principle; this the law of God will not allow, hence the failures.”

It appears that many Saints attributed abuses of the principle of plural marriage to incorrect choices of individuals. Not to the principle itself.

Positives and Negatives

Women recorded positive and negative experiences within polygamy. While many made the best of situations, I did find that the most positive reviews of polygamy tended to be in public discourse. When women were strengthening each other in meetings or defending the principle in speeches or in print.

In private journals and records, women were more likely to give vent to the frustrations and heartache they experienced in plural marriages, or other trials unique to polygamy.

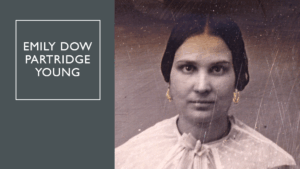

We see this in prominent women such as Emmeline B. Wells, Mary Isabella Horne, and Emily Dow Partridge Young.

Emily was one of Joseph Smith’s wives (and later a wife of Brigham Young). She recorded in her diary being “heart hungry all my life” and of being an “unloved ‘spiritual wife.’” The next day, though, she wrote:

“Aug 1st, 1881. Yesterday I was in a dark mood. Today I am looking for the bright spots, although they may be few and far between they should not be overlooked, and among my greatest blessings I class the fates that I am a mother, and was a spiritual wife.”

A Religious Duty

Matilda Griffing Bancroft, a prominent visitor to Utah in 1880, observed that Latter-day Saint women viewed polygamy as:

“A religious duty . . . and that it was a matter of pride to make everybody believe they lived happily and to persuade themselves and others that it was not a trial; and that long life of such discipline makes the trial lighter.”

I agree to an extent with Bancroft’s observation. We can see shadows of that mentality in the diary of Emily Young. Perhaps some Latter-day Saint women imagined that to be seen as truly strong and faithful, they had to steel themselves against difficulties living polygamously.

However, they did speak about those difficulties amongst themselves. Those conversations likely would have occurred privately. If they did occur publicly, they probably would have been spoken of in the context of how they overcame the difficulties of the practice.

Bright Spots

I do think many of the women, however, were sincere in what they saw as the “bright spots” in their faith-motivated decision to marry plurally. That they believed in the positive social, theological, and spiritual ramifications of polygamy. Even if they disliked the practice itself.

It is important to remember, too, that marital troubles are not unique to plural unions. Although I believe polygamy did present greater opportunity for difficulties because more personalities were involved. Sister wives could dramatically affect the positivity or negativity of the experience.

Some women, instead of hating polygamy, loved living in their large families. They enjoyed close relationships with their sister wives and many children. And they truly developed ties of love with the husband that they shared.

Common Misconception 4: All Latter-day Saints understood and agreed upon the doctrine and practice of plural marriage

Fantasy: All Latter-day Saints shared united beliefs supporting plural marriage. The doctrine was clear regarding it.

Reality: Both Church leaders and members sometimes presented conflicting messages regarding the doctrine of plural marriage. Messages could vary according to time period and place of residence. Not all Latter-day Saints supported the practice.

There was only about a three-year period in which Joseph Smith taught the doctrinal concepts of eternal marriage and plural marriage. Those three years were interspersed with periods of his being in hiding or in jail. His teachings were confined to a comparatively small group of Latter-day Saints.

The only record from Joseph Smith himself that discusses eternal and plural marriage exists as Doctrine and Covenants 132. Because the practice of plural marriage was not broadly established or openly discussed during Joseph Smith’s lifetime, not all Church leaders or members agreed on the particulars of the doctrine after Joseph Smith’s death. Varied teachings circulated.

Example

For example, Nauvoo polygamists may have shared memories of private conversations they had with Joseph Smith regarding the doctrine of polygamy. That would circulate. Church leaders who were taught by Joseph Smith in Nauvoo had additional and potentially different insights. Their words would circulate. Still others had different interpretations of verses in D&C 132. Some Church leaders would preach conflicting messages even within their own sermons.

On the whole, however, most polygamists believed that they would receive higher or additional blessings in the celestial kingdom for marrying plurally than would monogamous couples whose marriages were also temple sealings. For a practice that some believed was the highest form of marriage, plural marriage had remarkably little support in some families and communities.

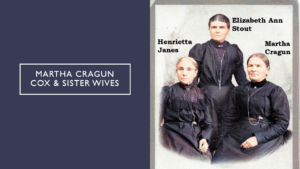

I find the story of Martha Cragun Cox insightful.

She recorded in her autobiography:

Martha’s Autobiography

“My decision to marry into a plural family tried my family—all of them—and in giving them trial, I was sorely tried. I had studied out the matter—I knew the principle of plural marriage to be correct—to be the highest, holiest order of marriage. Having decided to enter this order, it seemed I had passed the Rubicon. I could not go back, though I fain would have done so rather than incur the hatred of my family.

‘It was not a marriage of love,’ they claimed, and in saying so, they struck me a blow, for I could not say that I had really loved the man as lovers love, though I loved his wives and the spirit of their home. I could not assure my family that my marriage was gotten up solely on the foundation of love for man. The fact was, I had asked the Lord to lead me in the right way for my best good and the way to fit me for a place in His kingdom. He had told me how to go, and I must follow in the path.

Autobiography Continued

“When I came to know how generally my action in going into it was denounced—especially the fact I had married into poverty—I was saddened as well as surprised. When in my mind I took a survey of our little town, I could locate but a very few men—not one in fifty of the whole city—who had entered it at all.

“One who had been my admiring friend said: ‘It is all very well for those girls who cannot very well get good young men for husbands to take married men, but she (meaning me) had no need to lower herself, for there were young men she could have gotten.’ And she and other friends cold-shouldered me and made uncomplimentary remarks.”

1904 Second Manifesto

Some common questions included whether or not a person needed to marry plurally simply to reach the celestial kingdom. Or to qualify for the highest heaven in the celestial kingdom. Questions arose about how many wives one needed to fulfill the law of plural marriage. Who should marry plurally. And what D&C 132 meant on various points.

Members would write in to Church leaders to understand certain things. Answers could sometimes vary based on who was writing in response. That response would be shared locally. Communication was not as systematized or as quick as it is now.

It seems that Church leaders spoke with a more unified voice after the 1904 Second Manifesto.

As I mentioned earlier, working on Let’s Talk About Polygamy forced me to ask certain questions of myself. I would like to share some of those thoughts with you today.

Question 1: What was the role of agency in plural marriage?

The popular assumption in the nineteenth century—and sometimes in our time—is that polygamous men were lechers and women were victims of the system. Latter-day Saint women were appalled by accusations that they were duped or forced into plural marriages. They fiercely defended their role as agents in the marriage decision.

At an 1870 Indignation Meeting, Eliza R. Snow addressed the rumor that they were enslaved to Latter-day Saint men, stating:

“Our enemies pretend that in Utah, woman is held in a state of vassalage—that she does not act from choice, but by coercion—that we would even prefer life elsewhere, were it possible for us to make our escape. What nonsense! We all know that if we wished, we could leave at any time—either to go singly or we could rise en masse, and there is no power here that could or would ever wish to prevent us.”

Eyes Wide Open

In 1883, M. E. Talmage wrote in the Woman’s Exponent:

“I entered into plural marriage of my own free will, because I knew it was right. If the women did not know for themselves that the principle was true, or if they did not wish to embrace plural marriage, where is the man or set of men who could compel them to do so? Women very frequently decline to marry good, steady, single young men and marry one who has a family. Why? Because they believe they have the right to marry the man of their choice, and if they choose to marry a man who already has a wife, they think it is nobody’s business but their own.”

Many plural wives would add their voices to Talmage’s, saying they had chosen plural marriage with their eyes wide open. Trusting their husbands, trusting their sister wives, trusting the gospel of Jesus Christ as restored through Joseph Smith, and trusting that God had commanded that polygamy be lived once more among His chosen people. They wanted to show their faith by their works.

Divorce Allowed Women to Reclaim Agency

But what about the women who, once married polygamously, discovered it was not a lifestyle they wanted to continue? There were people who abused the system. What about those women who were victims of that abuse and did not feel they were free to choose?

At odds with the public perception that women were enslaved in plural marriages were Utah’s liberal divorce laws. These laws, passed by the Utah legislature in 1852, allowed for essentially “no fault” divorces. These “no fault divorces” were almost unheard of in other parts of the United States and the world, where it was difficult to obtain a divorce, if at all.

Additionally, being a divorced person—particularly a divorced woman—in the nineteenth century carried a heavy stigma. But not in Utah. It was common for divorced women to remarry in either polygamous or monogamous unions.

For women who were unhappy in polygamy, or who had felt pressured or forced into plural marriages, uncomplicated divorce practices allowed them to reclaim their agency.

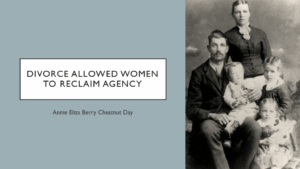

Annie Berry Chestnut Day

One of the most horrifying stories I read was in the autobiography of Annie Berry Chestnut Day. In 1879, when she was fourteen years old, Annie’s stepfather (who was nearly fifty years old) essentially tricked her into marrying him under the pretext that she was receiving her temple endowment. Annie’s mother was complicit in the idea. Annie did not realize she was married to the man she still called “pa” until after they left the temple.

Friends and even Church leaders urged her to leave the situation. After bearing three children, she obtained a divorce at the age of twenty-one. She is pictured here with her monogamous second husband, Thomas Day, and the three children from her previous marriage.

Emma Lynne Richardson

Likewise, fourteen-year-old Emma Lynne Richardson was pressured into plural marriage by her parents. She recalled:

“Some old fanatics were preaching that a young man could not save a girl if he married her. That to be saved she must marry some old codger tried and true. My parents got the disease with the rest, and when one of the tried and true came our way, they said I must marry him. I cried and begged, begged and cried, but to no avail. I was forced to marry him and go into his family.”

Thus, Emma was married to 61-year-old Freeborn DeMille in 1856.

Emma, too, obtained a divorce after several years. She went on to marry a man her age with whom she was happy. In both of these cases, the ease of obtaining divorces and the social acceptance of divorce allowed them to reclaim the agency they felt robbed of in their first marriages. They later both married men of their choosing.

Another question I needed to ask myself was:

Question 2: What do I believe about the nature of God?

This is a subjective question. For me, one of the challenging aspects of polygamy is thinking about its inherent inequality. Looking at polygamy numerically, it is unequal. Is it fair that a man can have more than one wife? Some polygamous women expressed feeling “second best” or yearned for the affection of a husband who was often absent or whose love and attention felt divided.

Is that fair? Would God give a commandment that was not fair?

I have heard some modern women express something to the effect of, “If I had to share my husband for eternity, it would be an eternity of hell.”

What about the majority of Latter-day Saint men and women in the nineteenth century who chose not to marry plurally, wanting to remain monogamous? Would God force His children into plural marriages, creating an eternity of heaven for some and hell for others?

That is not the God I know. The same God who fills me with love, peace, reassurance, forgiveness, and friendship as I have walked through my life. The same God who holds agency sacred. If He wants happiness for me here, why would He want misery for me there? I do not believe our Heavenly Parents desire unhappiness and suffering for any of us.

Fairness

From my perspective, polygamy was not fair. I believe some polygamous wives would agree with me. That it was not “fair” in the sense I have discussed. But they had faith it would be fair in the next life. They believed that their sacrifice here would be worth something there. That they would inherit special blessings for their unique obedience to this principle.

Does it matter, then, what I think?

That is where I step back and trust their ability to choose for themselves—their agency. That is where I acknowledge I do not know everything, nor do I feel I need to.

Abuses to plural marriage aside, most women and men acted according to their free will for their individual needs and reasons. There were a variety of reasons people chose to marry polygamously. Whether we believe it was right or wrong, it was their decision. Most acted according to their convictions of what they considered to be right.

We Were Created for Happiness

There is one thing I do know about the nature of God. He created us for happiness. There is no despair in the Great Plan of Happiness created for us by our Heavenly Parents.

There is little known about the kingdoms of glory in the next life. Or exactly what the nature of our relationships will be there. If it were possible, I would appease the worry, concern, and fear that has distressed people over this principle for about 180 years.

It worried people then, when people lived polygamously, and it worries people now, when it is no longer required.

According to their records, many polygamous wives turned to their faith in the nature of God and looked to Him for comfort. They looked to Him to fulfill His promises to them. Trusting they would receive eternal blessings to compensate for their sacrifices. Men did the same.

Earthly and Eternal Relationships

As I mentioned earlier, some men, and particularly women, felt the earthly and eternal relationships they gained through plural living were among its blessings.

Women like Martha Cragun Cox, wrote of her sister wives:

“To me it is a joy to know that we laid the foundation of a life to come while we lived in that plural marriage. That we three, who loved each other more than sisters—children of one mother love—will go hand in hand together down through all eternity. That knowledge is worth more to me than gold, and more than compensates for all the sorrow I have ever known.”

I believe everything will be okay. Even though I do not know how it will all work out, I do know that God loves His daughters as much as His sons.

Question 3: What are Modern Leaders Saying About Polygamy?

This is another important question I had to ask: “What are modern Church leaders saying about polygamy?”

Most teachings about plural marriage were spoken when the commandment to live plural marriage was in force. The commandment to marry polygamously is no longer in force. The sealing ordinance is an ordinance that existed then and that exists now. Thankfully, Elder Orson Pratt wrote out the entire sealing ceremony and published it in a periodical in 1853.

In an article published in the Ensign in 2015, Elder Marcus B. Nash confirmed that the words in the ceremony that sealed polygamous couples included identical promises and blessings as the words in the sealing ceremony of monogamous couples.

Thus, the potential for exaltation for monogamous and polygamous couples is now understood to be equal.

Question 4: What Does Polygamy Teach Us About God’s Definition of the Family?

This question also deserves attention and feels timely for the current climate in which we live. I believe one thing polygamy teaches us is that God’s definition of the family is more expansive than we sometimes allow it to be.

I suspect that some of us—consciously or subconsciously—carry what my husband calls the “baggage of polygamy.” Perhaps we feel that we must carry the burden of the Latter-day Saint polygamous past and all of the horrifying stories of the time. Perhaps we feel we must defend the practice without understanding it—like I did as a young seventh grader. Or perhaps we just don’t like or agree with it.

There have been several thoughts that helped me reframe how I think and feel about polygamy. I offer them to you with the hope that they may be useful.

Five Thoughts

First, I found great liberation as I began trusting the nineteenth-century Saints to have made their own decisions. Speaking in general terms, most polygamists were adults capable of saying “yes” and “no.” Some said yes to polygamy, and the majority of Latter-day Saints said no. These were decisions they made.

Second, I cannot fix the past. History happened. Bad things happened. Unfair things happened. It was messy. These are the Saints’ stories.

Third, they already bore the baggage of polygamy. Do I need to carry their pain as well? They bore the ridicule and mockery of others. They bore the difficulties in relationships, the heartache and sense of loss. Let that pain rest with them. They already lived it. They already bore it. I do not need to.

Fourth, go to the source. Learn the whole story. It is easy to misunderstand things. Study the whole life arc of a person.

Fifth, it is essential to combine both the aerial view and the street view of polygamy. The story of polygamy is best told from the perspective of the nineteenth-century Saints.

Conclusion

In writing this book, I felt it was my job to represent their stories—good and bad. The nineteenth-century Saints manifest the power of the human spirit to adapt and find love, forgiveness, and grace in difficult situations.

I truly believe that the history of polygamy in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not need to be a divisive or sensitive issue. It does not need to shake a person’s faith; it simply was. Polygamy is a topic to be acknowledged and discussed. It happened. It is history. And for most Saints, practicing it was a manifestation of faith.

Thank you.

Q&A

Scott Gordon: I have a few questions here.

Question:

Did the no-fault divorce laws only apply to plural marriages? Or did they also make divorce easy for monogamous marriages as well?

Brittany:

They’re kind of two different divorce systems, and they applied to both. You had a legal marriage with the first wife, and then sort of an ecclesiastical marriage with the plural wives. For the ecclesiastical marriages, you would just go to a Church authority, and you would be able to receive a divorce that way.

Legal marriages would be approached differently, but it was always quite straightforward.

Scott:

Which leads to the second question. In an address to the Saints, Brigham Young expressed that only he held the keys to polygamous marriage. That Saints could only enter into such marriages through his authority. So how can we account for the abuse of plural marriages you mentioned in your talk? Were others given the authority to officiate?

Brittany:

That’s a great question. So, there were thousands of Saints who participated in polygamy. There was a permissions process, just like this person mentioned, where theoretically every single plural marriage needed to be approved of by the President of the Church. But it was impossible for them to know thousands of people. So they relied heavily on the recommendations of local leaders to judge the worthiness of a man to have additional wives.

And interestingly, the question of the wife’s worthiness was never asked. It was always the worthiness of the man. So some slipped through, unfortunately.

Scott:

Unfortunately, yes. Could polygamy be an earthly practice only?

Brittany:

That’s a good question. I cannot answer that. And if I could, people would be very pleased to know what that is. But yeah, that’s an unanswerable question.

Scott:

So here’s your final question. Do you have a favorite story or a favorite woman that you found in your research?

Brittany:

Oh, there’s so many. I love Martha Cragun Cox’s story because she was just very authentic and honest about her feelings. I love the women especially who are just authentic and open—what they loved, what they hated about the practice. Not all records are like that. Some, like I mentioned, feel like they need to be tough and strong and that everything was rosy. But it was hard. It’s hard,

Scott:

Thank you so much.