August 2019

Inarguably, Jesus Christ is the most important figure described in the Book of Mormon and his name the most important used therein.[1] Apart from divine names and titles, however, the personal names Nephi and Laman and their gentilic derivatives—Lamanites and Nephites—appear to constitute the most important names in the Book of Mormon text. As Hugh Nibley understood, taking the Book of Mormon seriously as an ancient text means taking seriously the evidence of its onomasticon.[2]

In the accounts of ancient Israel’s ancestors—from Adam (‘humanity’) and Eve (‘life-giver’), and Noah (‘rest’), on down to Abraham (‘father of a multitude’), Isaac (‘may he laugh [rejoice]’), Jacob-Israel (associated with supplanting, struggling, and wrestling with God), Judah (‘praise’), Joseph (‘may he [God] add’), Ephraim (‘doubly fruitful’)—the actual meanings and perceived meanings of their names served as important keys to understanding the narratives told about them. The meanings of these names also sometimes had implications for their descendants. For example, the quasi-etymological, pejorative association of the name Jacob with ʿqb, ‘heel [noun]’ and ‘supplant [verb]’ in Genesis 26:25; 36:2) forms the basis for the prophet Jeremiah’s later criticism of Jacob’s descendants “every brother will utterly supplant [ʿāqôb yaʿqōb]” (Jeremiah 9:4 [MT 3]). The names Jacob and Israel, are further etiologized in the biblical text in terms of “wrestling” and “struggling” with God(s) and “men” (see Genesis 32:24-25, 28 [MT 25-26, 29]).[3] The perceived meaning of the name Judah—‘praise’ or ‘thanks’ (Genesis 29:35)—had implications in Jacob’s blessing for Judah’s descendants (Genesis 49:8, “Judah, thou art he whom thy brethren shall praise”), the Judahites or Jews: those to be “praised out of feeling of gratitude”[4] (cf. 2 Nephi 29:4, “what thank they [i.e., the Gentiles] the Jews”?). Even in the Deuteronomistic accounts of Israel’s early monarchic period Saul (‘asked’), David (‘beloved [of deity]’), Solomon (‘his replacement’ or ‘his peace’), the meaning of the kings’ names constitute important elements in the way their biographies are presented.[5]

Michael O’Connor has observed, “The ancients display awareness of the meanings and shapes of names chiefly in literature.”[6] Since Nephi’s small plates and Mormon’s abridgment of Nephite prophetic records more than qualify as literature (among other things), one cannot fully evaluate the onomastic evidence of the Book of Mormon without also investigating the awareness of the meanings and shapes of names within its text. Given the frequency and pervasiveness of the names Nephi and Nephites, Laman and Lamanites in the Book of Mormon, it behooves careful readers of the Book of Mormon to understand, as nearly as possible, what those names meant to those who used Lamanites and Nephites as sociological descriptors.

Hugh Nibley long ago noted that Lamanites and Nephites were “used … to designate not racial but political (e.g., Mormon 1:9), military (Alma 43:4), religious (4 Nephi 1:38), and cultural (Alma 53:10, 15; 3:10–11) divisions and groupings of people. The Lamanite and Nephite division was tribal rather than racial, each of the main groups representing an amalgamation of tribes that retained their identity (Alma 43:13; 4 Nephi 1:36–37).”[7] In this presentation, we will see evidence from the Book of Mormon in which the awareness of etymological meaning of Nephi (and Nephites) and the Nephite pejoration of the name Laman (and Lamanites) are both abundantly reflected in the text. This evidence suggests that the meaning of the name Nephi (‘good,’ ‘fair’), and the concept of “fair” in the context of Nephi’s vision of the tree of life as a foundational narrative, both shaped and reflected Nephite political, cultural, and religious self-perceptions long after Nephi’s time. Similarly, the Nephite pejoration of the name Laman and Lamanites reinforced negative Nephite attitudes toward and traditions regarding the Lamanites, also in the context of Nephi’s vision of the tree of life (we often underestimate the tremendous importance and influence of this vision over time). Just as Jacob, Israel, Judah, and Ephraim retained meaning as gentilic eponyms characterizing their descendants, it appears that the Nephites as ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones and Lamanites as those who had “no faith” or had dwindled in “unbelief” emerge as two of the most dominant onomastic motifs running throughout the Book of Mormon.

Part I – Nephi as Key-Word

Nephi as the “Good” Ancestor of the “Good” or “Fair Ones”

Over twenty-five years ago John Gee, using Semitic inscriptional evidence, convincingly argued that the Book of Mormon name Nephi best matches the Syro-Palestinian form of the common Egyptian name nfr during the Late Period.[8] As a personal name,[9] nfr would have been pronounced neh–fee, nay–fee,[10] or nou-fee[11] by Lehi’s time. The extremely common Egyptian lexeme nfr denotes ‘good,’ ‘fine,’ ‘goodly’ (of quality) or ‘beautiful, fair’ (of appearance), or “good, fair” (of character or repute).[12] As I have argued elsewhere, Gee’s suggestion has important implications for how we read numerous book of Mormon passages,[13] beginning with Nephi’s autobiographical introduction in the very first verse of the Book of Mormon:

I NEPHI having been born of goodly parents, therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father. And having seen many afflictions in the course of my days, nevertheless, having been highly favored of the Lord in all my days, yea, having had a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God, therefore I make a record of my proceedings in my days. (1 Nephi 1:1; emphasis in all scriptural citations added)[14]

Nephi plays on the meaning of his Egyptian name—‘good,’ ‘goodly,’ ‘fair’—in attributing the appropriateness of his own given name to the “goodly” character and quality of his own parents who helped set him on the spiritual path on which he would acquire a “great knowledge of the goodness … of God.” Kevin Barney[15] and John Gee have[16] argued—quite persuasively in my view—against the old canard that “goodly” in 1 Nephi 1:1 is somehow synonymous with “wealthy,” as I have also argued.[17] Enos’s similarly structured autobiographical introduction with its similar play on the meaning of Enos’s name (Heb. “man”)[18] also appears to confirm Nephi’s use of autobiographical wordplay:

| 1 Nephi 1:1 | Enos 1:1 |

| I Nephi [Egyptian nfr = “good,” “goodly”] | I Enos [Hebrew ʾĕnôš = “man”] |

| having been born of goodly parents, | knowing my father that he was a just man, |

| therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father | for he taught me in his language … |

Later Book of Mormon passages further support Nephi as a derivation from Egyptian nfr. For instance, Helaman explains the naming of his sons Lehi and Nephi thus: “Behold, I have given unto you the names of our first parents which came out of the land of Jerusalem. And this I have done that when you remember your names ye may remember them. And when ye remember them ye may remember their works. And when ye remember their works ye may know how that it is said, and also written, that they were good. Therefore, my sons, I would that ye should do that which is good, that it may be said of you, and also written, even as it has been said and written of them” (Helaman 5:6-7). The one extant available text that we have which states that their ancestors Lehi and Nephi (and their works) “were good” is 1 Nephi 1:1 where Nephi attributes the appropriateness of his own given name—Egyptian ‘good’—to his “goodly parents.”

Mormon later takes pains to show that, in fact, it was said of Helaman’s son, Nephi, that he and his works were “good”: “And it came to pass that thus they did stir up the people to anger against Nephi and raised contentions among them. For there were some which did cry out: Let this man alone, for he is a good man; and those things which he saith will surely come to pass except we repent” (Helaman 8:7).[19] Mormon thereby demonstrates that Nephi lived worthy of his ancestor’s ‘good’ name.

“Fair … Like unto My People”: The Roots of Nephite Cultural Self-Perceptions

Most Latter-day Saints who have studied the Book of Mormon at length are familiar with Mormon’s “O ye fair ones” lament in Mormon 6 (more on that in a moment). That lament’s characterization of the slaughtered Nephites as “fair ones” has a venerable history within the Book of Mormon. That history begins in Nephi’s vision of the tree of life, which clearly a cultural narrative for the Nephites throughout their entire history.[20] That vision appears to have defined Nephite political, cultural, and social self-understanding for most of that span.

When Nephi saw the latter-day Gentiles who would inhabit the New World, he describes them thus: “they were white and exceedingly fair and beautiful, like unto my people before they were slain” (1 Nephi 13:15). Amy Easton-Flake writes, “By this point in Nephi’s vision, the angel and Nephi have established through repetition that the color white is synonymous with partaking of the fruit: the fruit is white, the tree is white, and individuals who partake of the fruit are made white through the blood of the lamb.”[21] In other words, Nephi’s narratological use of terms indicates that these Gentiles, like his own people, have partaken of the fruit of the tree of life.[22] And here I would add that in using a term translated “fair” in 1 Nephi 13:15, Nephi creates a paronomastic association between his own name and partaking of the tree of life. If we take seriously the notion that Lehi’s and Nephi’s visions of the tree of life became a dominant cultural narrative for the Nephites, we must also take seriously the idea that this vision became the source for Nephite social codes like the association of whiteness and beauty with the acceptance of Nephite religious and political claims rather than simply constituting racial descriptions, as is so often assumed. When Nephi mentions that, at the time of their separation from the other Lehites, “all they which were with me did take upon them to call themselves the people of Nephi” (2 Nephi 5:9), they are not only taking upon them his name (‘good, fair’), but the description of the “white, and exceedingly fair and delightsome” ones (2 Nephi 5:21) who had partaken of the fruit of the tree of life in his vision vis-à-vis those who had “dwindled in unbelief” in 1 Nephi 12:22-23 (see again 1 Nephi 11–13).

This notion surfaces again in a prominent way in Zeniff’s royal autobiography (Mosiah 9–10), which Mormon appears to have included wholesale into his abridged narrative. Like Enos, Zeniff begins his autobiography in manner strikingly similar to that of Nephi:

| 1 Nephi 1:1 | Mosiah 9:1 |

| I NEPHI

having been born of goodly parents, therefore I was taught somewhat |

I Zeniff

having been taught in all the language of the Nephites |

| in all the learning of my father. And having seen many afflictions in the course of my days, nevertheless, | and having had a knowledge of the land of Nephi, or of the land of our fathers’ first inheritance, |

| having been highly favored of the Lord in all my days, yea, having had a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God, therefore I make a record of my proceedings in my days. | and I having been sent as a spy among the Lamanites that I might spy out their forces, that our army might come upon them and destroy them—but when I saw that which was good among them, I was desirous that they should not be destroyed. |

Zeniff’s autobiographical introduction, like Enos’s, exhibits textual dependence on Nephi’s autobiographical introduction in 1 Nephi 1:1, including the use of wordplay, here again involving the meaning of Nephi’s name: “good.” Zeniff’s own name might have reference to Nephi’s name—i.e., son of/descendant of Nephi (z3/s3 + a shortened form of Nephi; cf. Zenephi, Moroni 9:16).[23]

Zeniff’s wordplay on his own name, Nephi, and Nephites in terms of “good”— is significant. Brant Gardner suggests that at this point in time “those of the city of Nephi were linguistically Nephite but politically Lamanite.”[24] Zeniff would not have been “sent as a spy among the Lamanites” if his language and cultural identity had entirely differed from the inhabitants of the city of Nephi.

Thus, Zeniff’s use of the phrase “that which was good among them” constitutes a rhetorical cultural and religious reference. Brant Gardner is surely correct that “those of the city of Nephi had become Lamanites politically,” though they had probably not “abandoned all their religion immediately.”[25] Thus, Zeniff’s statements and Gardner’s observations make even more sense when we consider that the Nephites then, and previously, understood themselves as the ‘good,’ ‘goodly’ or ‘fair’ ones consistent with the Egyptian etymology of the name Nephi.

The force of Zeniff’s wordplay, then, is this: Zeniff— ‘descendant of Nephi’—saw “that which was good” or what he perceived as characteristically “Nephite” in terms of language, religion, and culture still extant among the inhabitants of the land and city of Nephi. These political “Lamanites” having “that which was [Nephite] among them” helps explain his subsequent comment, “I was desirous that they should not be destroyed.”

A similar conceptual framework stands behind Mormon’s treatment of the plight of Zeniff’s people years later as life began to unravel under king Noah after Abinadi’s martyrdom. His report echoes the meaning of the name Nephi and Nephites as ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones: “And it came to pass that those who tarried with their wives and their children caused that their fair daughters should stand forth and plead with the Lamanites that they would not slay them. And it came to pass that the Lamanites had compassion on them, for they were charmed with the beauty of their women” (Mosiah 19:13-14). Gardner believes that “the women provided a cultural excuse under which a surrender might be negotiated.”[26] Indeed, the characterization of Nephite women in terms of “fair” and “beauty” (vis-à-vis the Lamanites) reflects traditional Nephite self-perceptions—i.e., ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones as implied in the name Nephites and reflecting the positive description of those who partook of the tree in Nephi’s vision. But also here the characterization emphasizes at least one aspect of why, in Mormon’s view, the Lamanites sought political hegemony over the Nephites: they were attracted to what was ‘good’ or ‘fair’ even if to exploit it (see Mosiah 7:21-22; 9:12-13; 10:18).

An exchange between Aaron, the son of Mosiah II, and an unnamed Amlicite/Amalekite sheds further light on the political, cultural, and religious aspects of Nephite identity and self-perceptions. Whatever the relationship of these “Amalekites” to the Amlicites of Alma 2–3,[27] it is clear from Alma 43:13 that they had once been Nephites. Aaron attempts to preach in what Mormon characterizes as an Amlicite/Amalekite synagogue. The response to Aaron’s preaching and testimony reflects contemporary political and religious tension, but also reflects Nephite identity and self-perception: An unnamed Amlicite/Amalekite stands up and challenges Aaron’s preaching: “What is that that thou hast testified? Hast thou seen an angel? Why do not angels appear unto us? Behold are not this people as good as thy people?” (Alma 21:5).

The unnamed Amlicite’s fourth question is not merely a moral question, but also a cultural one: are not this people as Nephite as thy people? In other words, since the Amlicites/Amalekites were Nephite political and religious dissenters, the Amlicite was asserting the claim to being as ethnically and culturally Nephite as Aaron and the Nephites who remained loyal to the Nephite religious and political system.

Roughly fifty years later, we witness another, similar association between the Nephites and “good” ones. At the time that the office of chief judge passed from Nephi to a man named Cezoram, Mormon makes the comment that “they which chose evil were more numerous than they which chose good” (Helaman 5:2). One level, Mormon the Nephites had crossed the prophetic line drawn by Mosiah II (“And if the time cometh that the voice of the people doth choose iniquity, then is the time that the judgments of God will come upon you,” Mosiah 29:27). On still another level, the Nephites were becoming something other than what their own view of the name Nephites implied as a political, religious, and social description: ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones.

Nephi the son of Helaman noted exactly this when, from his garden tower, he inveighed against the widespread and increasing Nephite acceptance of the Gaddianton robbers and their methods: “Yea, woe be unto you because of that great abomination which has come among you; and ye have united yourselves unto it, yea, to that secret band which was established by Gaddianton. Yea, woe shall come unto you because of that pride which ye have suffered to enter your hearts, which has lifted you up beyond that which is good because of your exceedingly great riches” (Helaman 7:25-26). As Brant Gardner notes, “By saying it ‘has come among you,’ Nephi declares [the Gaddianton menace] to be foreign, not part of the Nephite tradition, an idea from the outside embraced by insiders that should have known better.”[28] Nephi’s further connection of the Gaddianton robbers with the Nephites’ “pride” and being “lifted up” (cf. Heb. rām and Rameumptom) appears to take aim at Cezoram, Seezoram, and possibly the same Zoramites whom Mormon later describes as continuing to the Nephites and even the righteous Lamanites (see 3 Nephi 1:29).[29] More to the point, the expression “beyond that which is good” lends further weight to the notion that the Gaddianton problem came in from outside. The Gaddianton robbers were distorting the Nephites into what was non-Nephite—something “beyond” their traditional self-perceptions and notions of “that which is good.”

Mormon presents Giddianhi using inverted, yet related rhetoric in order to flatter and intimidate Lachoneus and the Nephites into surrender and unification with the Gaddiantons in a letter preserved in 3 Nephi 3:2-10. Giddianhi closes his letter with an assertion of his name and title of authority over “the secret society of Gaddianton, which society and the works thereof I know to be good. And they are of ancient date and they have been handed down to us” (3 Nephi 3:9-10). Significantly, Giddianhi’s rhetoric attempts to assert both the Nephite-ness and possibly the Jaredite-ness[30] of the society. He employs a term here translated “good” to persuade the Nephites that the Gaddianton society’s works were consistent with Nephite religious and cultural self-identity, past and present. Yet, in the same breath he asserts their pre-Nephite antiquity in order to imbue them with greater authority and legitimacy. Mormon and Moroni, of course, both asserted that secret combinations of the Jaredite type ultimately destroyed both the Nephites and the Jaredites (see Helaman 2:13-14; Mormon 1:18; 2:8, 10, 27-28; cf. 8:9; Ether 8:21-23).

“O Ye Fair Ones” – Two Laments

In fact, Mormon highlights the role of the Jaredite-type secret combinations in the two greatest destructions that befell the Nephites: the destruction concomitant with the death of Christ and their final destruction (see Helaman 1–3 Nephi 7 [see especially 3 Nephi 6:28-30 and 7:6-9]; Mormon 1:18; 2:8, 10, 27-28). Mormon records that a “voice” was heard during the three days of darkness and cataclysms that attended or marked the death of Christ giving a “woe” oracle that sounds very much like a lament: “Woe woe woe unto this people! Woe unto the inhabitants of the whole earth except they shall repent, for the devil laugheth and his angels rejoice because of the slain of the fair sons and daughters of my people. And it is because of their iniquity and abominations that they are fallen.” (3 Nephi 9:2). The Lord here laments that the “fair ones” have become the “fallen” ones.

At the end of Nephi history, Mormon exclaimed the following lament as a wounded,[31] personal witness to the vast scene of slaughtered Nephites at Cumorah:

O ye fair ones,

how could ye have departed from the ways of the Lord!

O ye fair ones,

how could ye have rejected that Jesus,

who stood with open arms to receive you!

Behold, if ye had not done this,

ye would not have fallen.

But behold, ye are fallen,

and I mourn your loss.

O ye fair sons and daughters,

ye fathers and mothers,

ye husbands and wives,

ye fair ones,

how is it that ye could have fallen! (Mormon 6:17-19)

Mormon’s clearly drew the language of his own lament from the earlier woe-oracle from voice of Christ. However, Mormon’s lament also echoes Nephi’s vision of the tree of life and the “fall” of his people who had left the tree of life for the “great and spacious building,” which Nephi himself witnessed (1 Nephi 12:16-23; 15:5; cf. 11:35-36) and the religious, cultural, and social codes that emerged therefrom. Mormon clearly alludes to the traditional meaning of Nephites in terms of the etymological meaning of Nephi (nfr), ‘good’ or ‘fair.’ The scene epitomizes the dire consequences for people who had, contrary to their traditional self-identity, come to “delight in everything save that which is good” (Moroni 9:19).

Part II – Laman as Key-Word

Though attested as an ancient Semitic personal name at Ugarit[32] and as a Lihyanite inscription,[33] the etymological meaning of the name Laman remains something of an enigma. If the frequently paired name Lemuel—which transparently means ‘Belonging to El’—can be used as an analogue for Laman, perhaps we get nearer to how the name Laman might have been understood by Hebrew speakers and hearers, if not to an as-yet irretrievable etymology. In this scenario, the initial lĕ in Laman would, as in the name Lael (lāʾēl)[34] and the longer form lĕmô in Lemuel,[35] connote possession: ‘belonging to.’ In terms of sound, but not necessarily etymology, the remainder of the name evokes forms of the Semitic/Hebrew root ʾmn: ʾōmen (‘faithfulness,’ ‘trustworthiness’[36]), ʾāmēn (‘verily, truly,’[37] ‘surely!’ < ‘trustworthy’[38]), ʾēmun/ʾēmûn (adjective, ‘faithful, trustworthy’[39]; noun, ‘trusting, faithfulness,’[40] ‘faithfulness, trustworthiness’[41]), ʾĕmûnâ (‘faith,’[42] ‘firmness, steadfastness, fidelity’[43]; ‘steadfastness’; ‘trustworthiness, faithfulness’[44]). Thus it is possible to hear something akin to ‘belonging to [the God of] faithfulness’ or ‘belonging to [the God of] truth’ (cf. “God of truth,” “God of faithfulness,”[45] ʾĕlōhê ʾāmēn, Isaiah 65:16, cf. Christ as “the Amen” in Revelation 3:14; “the faithful God,” hāʾēl hanneʾĕmān, Deuteronomy 7:9) in the name Laman, whatever its actual etymology. It would have been, in any case, not only natural but almost irresistible for an Israelite to associate the name Laman with the root ʾmn on the basis of homonymy (i.e., a play involving similar sounds or paronomasia).

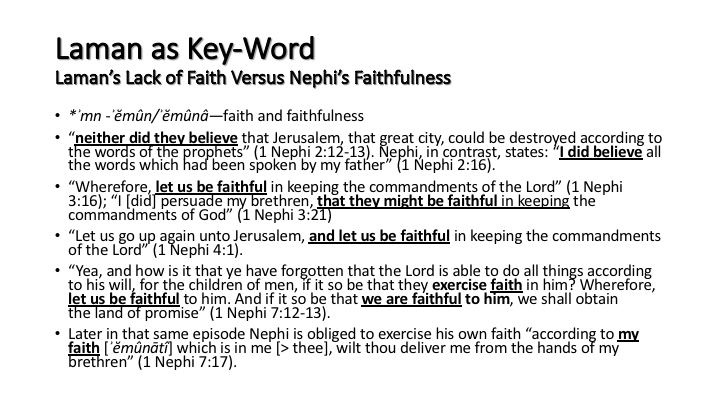

Laman’s Lack of Faith Versus Nephi’s Faithfulness

If the name Laman can be linked to Hebrew ʾmn—even if by sound association, whatever its real etymology—then Nephi’s emphatic attempts to contrast his faith with older brothers Laman’s and Lemuel’s lack of faith become far more than didactic ideation. Laman and Lemuel did not believe their father, “neither did they believe that Jerusalem, that great city, could be destroyed according to the words of the prophets” (1 Nephi 2:13). Nephi, in contrast, states: “I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father” (1 Nephi 2:16).

To brothers lacking covenant ʾĕmûnâ—faith and faithfulness—when seeking the plates of brass: “Wherefore let us be faithful in keeping the commandments of the Lord” (1 Nephi 3:16); “I [did] persuade my brethren that they might be faithful in keeping the commandments of God” (1 Nephi 3:21); “Let us go up again unto Jerusalem, and let us be faithful in keeping the commandments of the Lord” (1 Nephi 4:1); “Yea, and how is it that ye have forgotten that the Lord is able to do all things according to his will, for the children of men?—if it so be that they exercise faith in him. Wherefore, let us be faithful in him. And if it so be that we are faithful in him, we shall obtain the land of promise” (1 Nephi 7:12-13). Later in that same episode Nephi is obliged to exercise his own faith “according to my faith [ʾĕmûnātî] which is in me [> thee],[46] wilt thou deliver me from the hands of my brethren” (1 Nephi 7:17).

These passages help us appreciate the force of Nephi’s great thesis statement near the outset of his small plates record: “But behold, I Nephi will show unto you that the tender mercies of the Lord is over all them whom he hath chosen because of their faith [Heb. ʾĕmûnātām] to make them mighty even unto the power of deliverance” (1 Nephi 1:20). As Noel Reynolds has observed, “The content of Nephite tradition is much richer and more affirmative than that of the Lamanites. In fact, it centers on another subject altogether. As Nephi repeatedly states, his purpose is to persuade his children to believe in Christ, that they might be saved (1 Ne. 6:4; 19:18; 2 Nephi 25:23).”[47] He adds, “Without Christ the argument for Nephi’s authority has no basis and without Nephi’s authority the Nephite political claims collapse.”[48]

Thus, the Books of Nephi on the small plates served, in part, to explain why Laman and Lemuel and the Lamanite rulers who succeeded, were not divinely “chosen” religiously or politically. They also served to explain what Mormon says that some Lamanites recognized in later years, namely that “it was the Great Spirit that had always attended the Nephites, which had ever delivered them out of their hand” (Alma 19:27). All of it revolves around the Hebrew concept of ʾĕmûnâ, covenant ‘faith’ and ‘faithfulness’—a concept also foundational to Nephi’s doctrine of Christ (indeed, what activates it!) and a principle which also, not coincidentally, emerges from Lehi’s and Nephi’s vision of the tree of life (see especially 2 Nephi 31–32).[49]

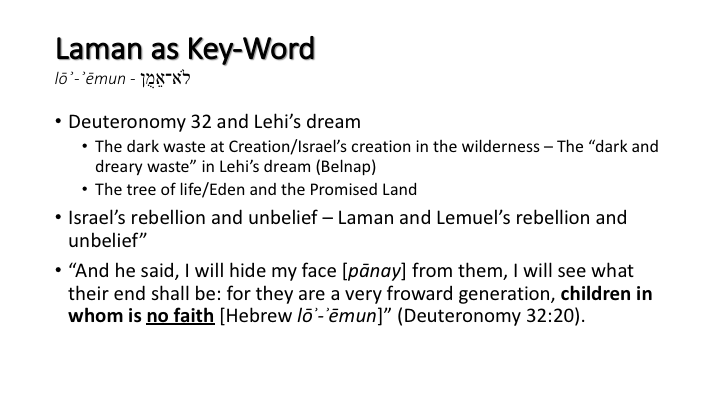

“Children in Whom Is No Faith”/ “These Shall Dwindle in Unbelief”

All of this brings us to one of the most important negative examples of ʾmn in the Hebrew Bible. Daniel L. Belnap has identified several important connections between Deuteronomy 32, a poetic text describing Israel’s “creation” in the language of cosmic creation, and Lehi’s dream.[50] For example, the earth being “without form and void [tôhû wābôhû; better, ‘empty and desolate’]” (Genesis 1:2) and the “wilderness” through which Israel traveled during its covenant creation (Deuteronomy 32:10) finds analogues in the “dark and dreary waste” through which Lehi travelled in his dream (1 Nephi 8:7) and the “wilderness” through which his family travelled.[51] The Lord’s guiding and instructing Israel through the wilderness (Deuteronomy 32:10) is mirrored in the “man … dressed in a white robe” who guides Lehi (1 Nephi 8:5),[52] and the Lord himself again when he appears “clothed in a white robe” at the temple in Bountiful after the earth is essentially re-created (see 3 Nephi 8:5-22; 10:10).[53]

To Belnap’s insights, I would add that Deuteronomy 32 also describes the fate of rebellious Israelites who violate Yahweh’s covenant: “And he said, I will hide my face [pānay] from them, I will see what their end shall be: for they are a very froward generation, children in whom is no faith [Hebrew lōʾ-ʾēmun]” (Deuteronomy 32:20). In other words, this poetic text describes Israelites who are cut off from Yahweh’s ‘face’/‘presence’ (pānîm). Their lack of “faith” or faithfulness—their ‘unbelief’—is described by the compound Hebrew noun lōʾ-ʾēmun [without vowels, lʾ-ʾmn]. When Nephi was shown a version of his father’s tree-of-life dream, his angelic guide showed him that his brothers’ posterity would eventually “overpower” or “overcome” the “the people of my seed.”[54] As subsequent verses make clear, this did not mean that none of Nephi’s posterity survived, but rather the legacy of Laman and Lemuel’s “unbelief” overcame “faith” in Christ, the one whom the tree of life symbolized: “And the angel said unto me: Behold, these shall dwindle in unbelief. And it came to pass that I beheld that after they had dwindled in unbelief, they became a dark and loathsome and a filthy people, full of idleness, and all manner of abominations” (1 Nephi 12:22-23). Easton-Flake suggests that “by calling the people a ‘dark, and loathsome, and filthy people’ (v. 23), Nephi connects them to symbols of hell—the filthy water and the dark mist.”[55]

The Lord’s hiding his “face” (pānîm) from degenerate Israelites finds a close analogue in the conditional “dynastic” promise to Lehi and Nephi. The iteration of this promise that accompanies the separation of the Nephites from the Lamanites runs thus: “Inasmuch as they will not hearken unto thy [i.e., Nephi’s] words, they shall be cut off from the presence of the Lord [pĕnê Yhwh]. And behold, they were cut off from his presence” (2 Nephi 5:20; cf. 1 Nephi 8:36).[56] Although language from later in Nephi’s vision suggests that both the surviving seed of Nephi as well as the seed of Laman et al. would “dwindle in unbelief” (see 1 Nephi 13:35) and Nephi’s explanation of his vision (see 1 Nephi 15:13; cf. also Lehi’s words in 2 Nephi 1:10), the Nephites generally equated “unbelief” with the Lamanites and their ancestral traditions.

“If Ye Will Not Believe”: Those Who “Believed” Nephi Versus “Unbelievers,” Including “Others,” as Lamanites

John Gee and Matthew Roper have demonstrated[57] that 2 Nephi 5:6 is key to understanding the composition of Nephite polity from the very beginning: “Wherefore it came to pass that I Nephi did take my family, and also Zoram and his family, and Sam mine elder brother and his family, and Jacob and Joseph, my younger brethren, and also my sisters, and all they which would go with me. And all they which would go with me were they which believed in the warnings and the revelations of God; wherefore they did hearken unto my words” (2 Nephi 5:6). The key word here is “believe,” in Hebrew causative form of ʾmn. Nephi uses it (or its scribal equivalent) to distinguish his people from “the people which were now called Lamanites” (2 Nephi 5:14).

2 Nephi 5:23 points to not only future, but almost immediate intermarriage and political unification with those Nephi denominates “Lamanites.” Gee and Roper write: “Unidentified people had, at this early period already joined with the Lamanites in their opposition to Nephi and his people and had become like the Lamanites, and Nephi saw this event as a fulfillment of the Lord’s prophecy.”[58] Moreover, they continue, “Nephi’s statement about unidentified peoples intermarrying with the Lamanites seems to indicate the presence of other Lehite peoples who had joined or were joining the Lamanites at the time of Nephi.”[59] Gee and Roper further propose that Nephi’s and Jacob’s early uses of Isaiah pertained to the incorporation of Gentile “others” among those who supported Nephi and “Zion.” If they are correct, the unnuanced traditional assumption that the term Lamanites functions primarily as a racial designation widely misses the mark.

In terms of their use of the prophecies and writings of Isaiah, Nephi and Jacob (at Nephi’s behest) quote a lot of texts that pertain to Zion, its establishment, and opposition thereto (e.g., Isaiah 52:7-10 in 1 Nephi 13:13; Isaiah 49:14-18 in 1 Nephi 20:14-18; Isaiah 29:8 in 1 Nephi 22:14, 19; 2 Nephi 6:13; 27:3). If, as seems clear, that the verb “believe”—Hebrew ʾmn—constitutes the most important term in 2 Nephi 5:6 as distinguishing those who supported Nephi’s leadership claims from those who supported Laman, the use of the same verb in the Isaiah passages that Nephi and Jacob quote begs further scrutiny.

Jacob, perhaps at the temple,[60] declares the following regarding those, including “believing” Gentiles then present (cf. 2 Nephi 5:6),[61] who “believe” in the Messiah and consequently Nephi’s claims to power versus those who “fight against zion” (2 Nephi 6:13): “when that day cometh when they shall believe in him; and none will he destroy that believe in him and none will he destroy that believe in him. And they that believe not [cf. Heb. lōʾ heʾĕmînû] in him shall be destroyed, both by fire, and by tempest, and by earthquakes, and by bloodsheds, and by pestilence, and by famine. And they shall know that the Lord is God, the Holy One of Israel” (2 Nephi 6:14-15). Blending in imagery from Isaiah 29,[62] Jacob directly alludes to one of the important “messianic” Zion prophecies in Isaiah which describes a Davidic “corner stone” laid as the first building block of Zion’s foundation: “Therefore thus saith the Lord God, Behold, I lay in Zion for a foundation a stone, a tried stone, a precious corner stone, a sure foundation: he that believeth [hammaʾămîn] shall not make haste” (Isaiah 28:16; cf. Moses 7:53). Notably, Jacob goes back to this same Isaianic text as a preface for his quotation of Zenos’s allegory of the olive tree (see Jacob 4:16-17). The fundamental question in Jacob 4–6, as Jacob frames it, pertains to Judahite-Israelite rejection of the Messiah, a problem shared by the Lamanites: “how is it possible that these, after having rejected the sure foundation, can ever build upon it that it may become the head of their corner?” (Jacob 4:17).

Nephi quotes and likens a second relevant passage from the Isaianic corpus in order emphasize to his audience (immediate and latter-day) the importance of having and maintaining covenant faith and faithfulness. Gee and Roper suggest the following recontextualization of Isaiah 7 in 2 Nephi 17 the nascent people of Nephi, which would have included Gentiles “who believed in the warnings and the revelations of God”:

Within forty years of Lehi’s departure from Jerusalem (see 2 Nephi 5:34), perhaps after thirty years in the promised land (see 1 Nephi 17:4), Nephi notes that ‘we had already had wars [i.e., large-scale conflicts] and contentions with our brethren’ (2 Nephi 5:34). In his ambition to gain power and assert his claims to rulership, Laman, leader of “the people who were are [sic] now called Lamanites” (2 Nephi 5:14), has made war on another ruler of Israelite descent, Nephi and his people (see 2 Nephi 5:1-3, 14, 19, 34). Perhaps frightened by the superior numbers of their enemies, the people are counseled to trust in the Lord, since those who fight against Zion will end up licking the dust of the feet of the covenant people of the Lord (see 2 Nephi 6:13; 10:16).[63]

The key phrase in Isaiah 7 and thus in 2 Nephi 17 is “If ye will not believe, surely ye shall not be established”(Isaiah 7:9; 2 Nephi 17:9); or, “If you do not stand firm in faith, you shall not stand [i.e., be firm] at all” (NRSV). In Hebrew this is a polyptotonic[64] phrase, ʾim lōʾ taʾămînû kî lōʾ tēʾāmēnû, which plays on a negation of forms of the verb ʾmn in two of its stems. If Gee’s and Roper’s interpretation of 2 Nephi 17 is correct, then I propose that the phrase ʾim lōʾ taʾămînû kî lōʾ tēʾāmēnû functions as a deliberate paronomasia on Laman and Lamanites along the lines of “unbelief” (lōʾ-ʾēmun, Deuteronomy 32:20) in 1 Nephi 12:22-23.

Isaiah’s message of encouragement to Ahaz in Isaiah 7:9 amounted to “have faith and be faithful.”[65] Nephi’s likening of this passage and its message to his people and the emerging Lamanite threat would have been, “if you have no faith, it is because you are not faithful”—i.e., you will become like the Lamanites, those who had “dwindled in unbelief” or “children in whom is no faith” (Deuteronomy 32:20). This appears to have happened to many of the Nephites by the time chronicled in the Book of Omni (see especially Omni 1:5-7).

Generational and Cultural “Unbelief”

Writing near the end of his life, Jacob described Lamanite obduracy “many means were devised to reclaim and restore the Lamanites to the knowledge of the truth [cf. Heb. ʾemet < ʾmn]; but it all were vain, for they delighted in wars and bloodshed, and they had an eternal hatred against us their brethren” (Jacob 7:24). Enos and Jarom describe Lamanite culture in similar stark, negative terms (see Enos 1:20; Jarom 1:6) that recall Nephi’s vision (1 Nephi 12:23). Nevertheless, Jacob had commended what was “better” in Lamanite culture than the culture of the ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones: “Behold, [the Lamanite] husbands love their wives, and their wives love their husbands, and their husbands and their wives love their children; and their unbelief and their hatred towards you is because of the iniquity of their fathers; wherefore how much better are you than they in the sight of your great Creator?” (Jacob 3:7).

Here Jacob’s rhetoric trades on an already-developed Nephite pejoration of the name Lamanites in terms of “unbelief” (lōʾ-ʾēmun). But, importantly, Jacob’s rhetorical question turns the Nephites’ own religious and cultural self-perceptions—that they were the ‘good’ or ‘fair’ ones—against them. Since both Egyptian and Hebrew form comparatives using adjective and a preposition[66] Jacob’s question would literally would have been something like: “how much [more] good are you than they.” Jacob emphasized that the Nephites as the ‘good’ or “fair’ ones were not morally superior to the Lamanites. Even some aspects of Lamanite culture, such as their family relationships, were “better”—or more ‘good’—than Nephite culture. Jacob’s allusion to “white” skin color (v. 8) is another allusion back to Nephi’s vision (1 Nephi 13:15; cf. 12:23).

Nevertheless, Nephites after Jacob continued to identify the Lamanites with “unbelief.” King Benjamin, who had “caused” his sons “to be taught” the language or script in which the brass plates were written so that they could read and understand them (Mosiah 1:2-3), noted that without these scriptures and the ability to read them, “even our fathers would have dwindled in unbelief, and we should have been like unto our brethren the Lamanites which know nothing concerning these things, or even do not believe them when they are taught them, because of the traditions of their fathers, which are not correct” (Mosiah 1:5).[67] Benjamin’s words revolve around the traditional Nephite pejorative association of the names Laman and Lamanites with “unbelief” (cf. 1 Nephi 12:22-23; Heb. lōʾ-ʾēmun) and “not believing” (lōʾ heʾĕmînû).[68]

Describing the events of the Amlicite crisis, Mormon offers a broad definition of “Lamanites,” stating: “whosoever suffered himself to be led away by the Lamanites were called under that head” (Alma 3:10). Mormon recapitulates Nephi’s concern from the small plates about “mixing” (2 Nephi 5:23), suggesting that the Nephite concern continued to be “that they might not mix and believe in incorrect traditions, which would prove their destruction” (Alma 3:8). Here again Mormon uses the religious verb “believe”/ʾmn to differentiate Lamanites from the Nephites. In other words, “Lamanite” had much more to do with “not believing” than any ethnic considerations. It was a descriptor that connoted primarily religious (an absence of faith in Jesus Christ), but also political, and social disloyalty from the Nephite perspective.

In the succeeding verses, Mormon repeats this verb three additional times as play on “Lamanites” in terms of “unbelief”: “And it came to pass that whosoever would not believe in the tradition of the Lamanites, but believed those records which were brought out of the land of Jerusalem, and also in the tradition of their fathers, which were correct, which believed in the commandments of God and kept them, were called the Nephites or the people of Nephi, from that time forth” (Alma 3:11). Mormon’s language represents another permutation of the Lamanites/unbelief theme. Regarding this very passage, Reynolds notes, “being a Nephite politically religiously and socially eventually turned on accepting the Nephite traditions and records.”[69] Yet again, ʾmn in conjunction with the Laman and Lamanites constitutes the key term. Even after the conversion of many Lamanites, as chronicled in Alma 17–28, Mormon characterizes Nephite defection and apostasy as “to dwindle in unbelief and mingle with the Lamanites” (Alma 50:22).

Part III – Reversal: Mormon’s Emphasis on Lamanite Faithfulness and the Lamanites Becoming “Good” (Nephite)

Blending the language of Isaiah 55:1-3 and the vision of the tree of life (e.g., the invitation to “come unto” Christ/the tree of life)[70] seen by him and his father, Nephi makes it clear that God’s doing “good” and his “goodness” were not delimited to the Nephites: “For he doeth that which is good among the children of men. And he doeth nothing save it be plain unto the children of men. And he inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness. And he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile” (2 Nephi 26:33). Regarding this passage, Gee and Roper remark: “Nephi’s emphasis [in 2 Nephi 26:33] on the universal nature of God’s love is even more meaningful if written and taught to a people grappling with issues of ethnic and social diversity.”[71] Even after the departure of Nephi and “all they which would go with [him]” (not a homogenous group), Nephite attempts to reclaim the Lamanites (probably an even more diverse group) continued: “For we labor diligently to write, to persuade our children and also our brethren to believe in Christ” (2 Nephi 25:23).

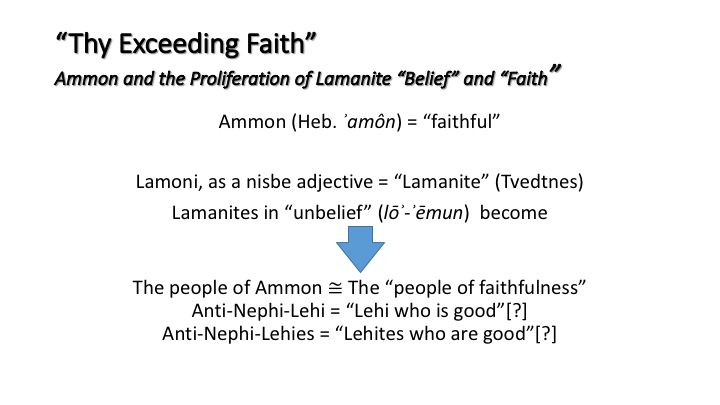

“Thy Exceeding Faith”: Ammon and the Proliferation of Lamanite “Belief” and “Faith”

The authors who wrote on Nephi’s small plates are consistent in describing the futility of earlier evangelization and reclamation efforts (Jacob 7:24; Enos 1:14, 20, “to restore the Lamanites to the true faith in God” [v. 20]). Mormon’s pre-Benjamin large plates abridgement very likely reflects the same reality. Thus one of Mormon’s overarching narrative aims is to show how traditional Lamanite “unbelief” became model belief and faith. The first major turning point occurs with the mission of Ammon and the other royal sons of Mosiah to the Lamanites.

When Mosiah II “inquired of the Lord if he should let his sons go up among the Lamanites to preach the word” (Mosiah 28:6), the Lord’s response came, “Let them go up, for many shall believe [cf. Heb. yaʾămînû] on their words” (Mosiah 28:7), In the Lord’s response we hear a gentle rebuke of the traditional Nephi association of the Lamanites with “unbelief” (cf. Heb. lōʾ-ʾēmun) as well as a paronomasia on the name Ammon, the Lord promises Mosiah the beginning of the reversal that “unbelief.” And so, Ammon, his brothers, and those who went with them commenced their mission “to bring, if it were possible, their brethren the Lamanites, to the knowledge of the truth, to the knowledge of the baseness of the traditions of their fathers, which were not correct” (Alma 17:9).

As noted previously, one of the traditional grievances against the Nephites concerned the right to rule,[72] a political issue. Knowing this, Ammon assumes the role of a servant rather than a ruler, in his words, “to win the hearts of these my fellow-servants, that I may lead them to believe in my words” (Alma 17:29).

Ammon quickly distinguishes himself by his “faithfulness.” Given the homonymy between Ammon and the Hebrew root ʾmn in its various forms—the root from which the name Ammon (Heb. ʾamôn = “faithful”)[73] might ultimately derive,[74] this appears to be a supremely fitting narrative detail. Mormon makes thoroughgoing use of this paronomastic association throughout the Lamanite conversion narratives, presenting Ammon as the catalyst through which many Lamanites transition from trenchant “unbelief” to unshakable “faithfulness.” Following Ammon’s rout of those plundering Lamoni’s flocks, Mormon records, “And when they had all testified to the things which they had seen and [Lamoni] had learned of the faithfulness [Heb. ʾĕmûnat] of Ammon in preserving his flocks, and also of his great power in contending against those who sought to slay him, he was astonished exceedingly and said: Surely [Heb. ʾomnām], this is more than a man” (Alma 18:2). Lamoni subsequently learns that Ammon’s “faithfulness” extends beyond the keeping of flocks. Mormon reports his response: “Now when king Lamoni heard that Ammon was preparing his horses and his chariots, he was more astonished because of the faithfulness [Heb. ʾĕmûnat] of Ammon, saying: Surely [Heb. ʾomnām] there has not been any servant among all my servants that has been so faithful [Heb. neʾĕmān] as this man, for even he doth remember all my commandments to execute them” (Alma 18:10; cf. 1 Samuel 22:14).[75]

The events of Alma 18-19 subsequently witness a proliferation of ʾmn-terminology. The verb “believe” (< ʾmn) occurs seventeen times, the passive form “faithful” (neʾĕmān) once, faith”/“faithfulness” (Heb. ʾĕmûnâ) six times, and “true,” “trust,” and “unbelief” once each in Alma 18–19.[76] Mormon presents three Lamanite figures as vocally pledging their “belief” in Ammon’s and Aaron’s words and thus also in Nephite tradition and thus also in Jesus Christ as Messiah. Lamoni promises Ammon, “Yea, I will believe all thy words” (Alma 18:23; cf. “the king believed all his words,” v. 40); Lamoni’s wife’s declares to Ammon “I have no witness save it be thy word and the word of our servants. Nevertheless I believe it shall be according as thou has said” (Alma 19:9, in response to Ammon’s question, “believest thou this?”); and Lamoni’s father’s statements, “And if now thou sayest there is a God, behold, I will believe”; “I believe that the Great Spirit created all things”; and “I will believe all thy words” (Alma 22:7, 10-11). All three persons—Lamoni, Lamoni’s wife, and evidently Lamoni’s father—are blessed with visions of the premortal Jesus Christ, mirroring the three of witnesses of the premortal Christ mentioned by Nephi in 2 Nephi 11:2-3 after the pattern of Deuteronomy 17:6; 19:15.

Ammon’s response to Lamoni’s wife, “Blessed art thou because of thy exceeding faith. I say unto thee, woman, there has not been such great faith among all the people of the Nephites” (Alma 18:10) becomes broadly true of the converted Lamanites in Mormon’s narrative. In one of his most important summarizing statements regarding the Lamanite converts, Mormon declares:

And thousands were brought to the knowledge of the Lord; yea, thousands were brought to believe in the traditions of the Nephites. And they were taught the records and prophecies which were handed down even to the present time. And as sure as the Lord liveth, so sure as many as believed, or as many as were brought to the knowledge of the truth through the preaching of Ammon and his brethren according to the spirit of revelation and of prophecy and the power of God working miracles in them—yea, I say unto you, as the Lord liveth, as many of the Lamanites as believed in their preaching and were converted unto the Lord never did fall away. (Alma 23:5-6; cf. Helaman 5:12)

Nephite kingship, as a political institution, had ceased with Ammon’s father, Mosiah II and arguably this is one reason why Ammon et al.’s was mission so successful. Christ’s kingship as the “sure foundation”—decoupled from Nephite kingship—by this point constituted the prerequisite for covenant ʾĕmûnâ. Ammon himself did not seek kingship or royal authority and eschewed such when offered it (Alma 17:24-25; 20:21-27; cf. Isaiah 28:16; Helaman 5:12).[77]

Mormon later records that the offspring of king Noah’s priests (“the seed Amulon and his brethren”) “having usurped the power and authority over the Lamanites, caused that many of the Lamanites should perish by fire because of their belief” (Alma 25:4-5). This, in turn, caused many more Lamanites “to disbelieve the traditions of their fathers, and to believe in the Lord, and that he gave great power unto the Nephites [cf. 1 Nephi 1:20]; and thus there were many of them converted in the wilderness” (Alma 25:6; cf. Alma 25:11).

Recalling the evident association of the name Ammon with “faithful” and “faithfulness” in Alma 18:2, 10, we can better appreciate another of Mormon’s significant summative statements: “And they were called by the Nephites the people of Ammon; therefore they were distinguished by that name ever after. And they were numbered among the people of Nephi, and also numbered among the people who were of the church of God. And they were also distinguished for their zeal towards God and also towards men; for they were perfectly honest and upright in all things. And they were firm in the faith [ʾĕmûnat] of Christ, even unto the end” (Alma 27:26-27). The Nephites apparently avoided using “Lamanites” to refer to Ammon’s converts. These Lamanites, formerly “unfaithful” became the “people of Ammon”—the people of exceeding faith and faithfulness (Anti-Nephi-Lehi[es] = “Lehi/Lehites who is/are good”[?]).

The “Exceeding Faith” of the Stripling Warriors: Lamanite Faithfulness in the Second Generation

In the second generation, Helaman writes a letter to Moroni regarding the sons of the people of Ammon. In setting the stage for his description of their surpassing faith and faithfulness: Helaman recalls the age old association between the name Laman and “unbelief” (cf. lōʾ-ʾēmun):

“Behold, two thousand of the sons of those men which Ammon brought down out of the land of Nephi—now ye have known that these were a descendant of Laman, who was the eldest son of our father Lehi—now I need not rehearse unto you concerning their traditions or their unbelief, for thou knowest concerning all these things” (Alma 56:3-4).

But then Helaman proceed to favorably compare the observed faithfulness of these young men to that of both the unconverted Lamanites and the Nephites: “But behold, my little band of two thousand and sixty fought most desperately. Yea, they were firm before the Lamanites … And as the remainder of our army were about to give way before the Lamanites, behold, these two thousand and sixty were firm and undaunted. Yea, and they did obey and observe to perform every word of command with exactness. Yea, and even according to their faith [ʾĕmûnātām] it was done unto them. And I did remember the words which they said unto me that their mothers had taught them” (Alma 57:19-21). The key word or concept here, as a play on Lamanites, is ʾĕmûnâ. Consistent with Alma’s description of the converted Lamanites (or people of Ammon) in Alma 23:5-6; 27:26-27), Helaman’s stripling “sons” have more “faith” and “faithfulness” than the Nephites or the unconverted Lamanites. Helaman cites their “firm”-ness, a related ʾmn-concept, as proof. The ʾĕmûnâ of these young men stemmed from that of their mothers.

Although these formerly “Lamanite” parents had been tempted to break their covenant, Helaman prevailed upon them not to do so. Their children thus received reciprocal covenant blessings—and power—for their parents covenant maintenance: “And now, their preservation was astonishing to our whole army, yea, that they should be spared while there was a thousand of our brethren who were slain. And we do justly ascribe it to the miraculous power of God, because of their exceeding faith [cf. Hebrew ʾĕmûnātām] in that which they had been taught to believe—that there was a just God, and whosoever did not doubt, that they should be preserved by his marvelous power” (Alma 57:26). The implications of this episode are clear: the ʾĕmûnâ—the covenant faithfulness—of the converted Lamanites “exceed[ed]” the “faith” and the covenant “faithfulness” of the Nephites even in the second generation. At the conclusion of his letter, Helaman returns to this theme essentially as an inclusio to Alma 56:3-4 and his mention of Ammon, Lamanites, and unbelief: “their faith [ʾĕmûnātām] is strong in the prophecies concerning that which is to come” (Alma 58:40)—i.e., in Jesus as the Christ.

“The Nephites Did Begin to Dwindle in Unbelief … While the Lamanites Began to Grow in Righteousness”: Lamanite Faithfulness in the Third Generation

Mormon endeavors to draw an even clearer and ironic distinction, roughly fifty years later, between the unfaithfulness of the Nephites and the faithfulness of the converted Lamanites, whom the Nephites traditionally had viewed and characterized as those who had “dwindled in unbelief.” Mormon mentions that the Nephites “had altered and trampled under their feet the laws of Mosiah” and that “their laws had become corrupted, and that they had become a wicked people, insomuch that they were wicked even like unto the Lamanites. And because of their iniquity the church had begun to dwindle. And they began to disbelieve in the spirit of prophecy and in the spirit of revelation. And the judgments of God did stare them in the face” (Helaman 4:22-23). A collective loss of the spirit had left them in “a state of unbelief and awful wickedness” such that “the Lamanites were exceedingly more numerous than they; and except they should cleave unto the Lord their God they must unavoidably perish” (Helaman 4:25). Traditional Lamanite “unbelief” had become Nephite unbelief, as emphasized with additional onomastic wordplay.

In Helaman 5, as a prelude to a second set of mass Lamanite conversions Mormon goes even further in his characterization of Nephite apostasy. The moral line mentioned by Mosiah II in Mosiah 29:27-28 (“if the time cometh that the voice of the people choose iniquity…”)[78] had now been crossed: “they which chose evil were more numerous than they who chose good, therefore they were ripening for destruction, for the laws had become corrupted” (Helaman 5:2). Mormon alters the language of Mosiah II’s letter (“desir[ing] … that which is right” vs. “desire that which is not right” and “choose iniquity”) to “they who chose evil” vs. “they who chose good.” The latter description at this seminal moment in Nephite history, deliberate in its diction, had important implications for the Nephites, not only in the wider context of their own history, but for their ongoing self-identification as the “good” or “fair ones” which they had largely ceased to be, as they would again during Mormon’s own time.

Even after the conversion of “eight thousand of the Lamanites” (Helaman 5:19) and the reconversion of numerous Nephite “dissenters” (Helaman 5:18) which resulted in a general “peace” (Helaman 6:7, 13-14) and “great joy” (Helaman 6:3, 14) in the church because of the conversion of the Lamanites, nevertheless “there were many of the Nephites who had become hardened and impenitent and grossly wicked, insomuch that they did reject the word of God and all the preaching and prophesying which did come among them” (Helaman 6:2). Regarding the degeneracy of the “more part” of the Nephites and their embrace of satanic Gaddiantonism (see Helaman 6:21-33), Mormon concludes, “And thus we see that the Nephites did begin to dwindle in unbelief and grow in wickedness and abominations, while the Lamanites began to grow exceedingly in the knowledge of their God. Yea, they did begin to keep his statutes and commandments and to walk in truth and uprightness before him” (Helaman 6:34). Mormon’s picture here is striking: Nephites had come to embody the “unbelief”—the lōʾ-ʾēmun—traditionally affixed to the Lamanites, while the Lamanites had become the picture of ʾĕmûnâ—faith and covenant faithfulness.

Samuel the Lamanite’s Seminal Semiotic Speech

Mormon appears to have been setting the stage all throughout his abridged Book of Helaman—and I would argue much earlier—for Samuel the Lamanite’s prophetically majestic[79] and rhetorically incisive speech. In this speech, given atop the walls of Zarahemla to an audience of proud, apostate, and recalcitrant Nephites, Samuel plays on and overturns all of the traditional rhetoric that characterized the Lamanites in terms of “unbelief” and a lack of faith:

And behold, ye do know of yourselves, for ye have witnessed it, that as many of them as are brought to the knowledge of the truth and to know of the wicked and abominable traditions of their fathers, and are led to believe the holy scriptures—yea, the prophecies of the holy prophets which are written, which leadeth them to faith on the Lord and unto repentance, which faith and repentance bringeth a change of heart unto them—therefore as many as have come to this, ye know of yourselves are firm and steadfast in the faith and in the thing wherewith they have been made free. And ye know also that they have buried their weapons of war, and they fear to take them up lest by any means they shall sin; yea, ye can see that they fear to sin. For behold, they will suffer themselves that they be trodden down and slain by their enemies and will not lift their swords against them—and this because of their faith [ʾĕmûnātām] in Christ. And now because of their steadfastness when they do believe in that thing which they do believe, for because of their firmness when they are once enlightened, behold, the Lord shall bless them and prolong their days, notwithstanding their iniquity. Yea, even if they should dwindle in unbelief the Lord shall prolong their days, until the time shall come which hath been spoken of by our fathers, and also by the prophet Zenos and many other prophets, concerning the restoration of our brethren the Lamanites again to the knowledge of the truth. (Helaman 15:7-11)

Samuel’s, which relies heavily on the speech forms[80] and rhetoric of earlier prophets, employs a polyptotonic[81] repetition on forms of ʾmn, apparently including ʾĕmûnâ (“faith”) and ʾemet (“truth”), as a dramatic means of illustrating contemporary Lamanite faithfulness and observance of the doctrine of Christ and mercilessly overturning the traditional Nephite association of the Lamanites with “unbelief” and a lack of faithfulness. For Samuel (and Mormon), the generational faithfulness of the converted Lamanites for more than seventy years constituted an unimpeachable testimony of the strength and surety of their conversion.

Far from dialing the rhetoric back at this point Samuel plays on the Nephites in terms of the notion of “good” or “fair ones” before bringing the pejorative lōʾ-ʾēmun/Laman association full circle:

Therefore I say unto you: it shall be better [literally “good”] for them than for you except ye repent. For behold, had the mighty works been shewn unto them which have been shewn unto you—yea, unto them who have dwindled in unbelief because of the traditions of their fathers—ye can see of yourselves that they never would again have dwindled in unbelief. Therefore, saith the Lord: I will not utterly destroy them, but I will cause that in the day of my wisdom they shall return again unto me, saith the Lord. And now behold, saith the Lord concerning the people of the Nephites, if they will not repent and observe to do my will, I will utterly destroy them, saith the Lord, because of their unbelief, notwithstanding the many mighty works which I have done among them. And as surely as the Lord liveth shall these things be, saith the Lord. (Helaman 15:14-17)

Samuel declares that it will be “better,” literally “good,”[82] for the Lamanites—“them who have dwindled in unbelief” than for the “good” or “fair ones” at the final judgment. Samuel appears to echo Jacob earlier, similar excoriation of the Nephites in similar terms: “their unbelief and their hatred towards you is because of the iniquity of their fathers; wherefore, how much better are you than they, in the sight of your great Creator?” (Jacob 3:7).

Samuel also invokes the evidence of the Nephites own eyes. Mormon had regarding the first Lamanite conversions fifty years earlier: “as many of the Lamanites as believed in their preaching, and were converted unto the Lord, never did fall away” (Alma 23:6). For fifty years, the Nephites had the evidence of experience for Samuel’s assertion that so enlightened “they never would again have dwindled in unbelief.”

But Samuel goes even further: the Lord will “utterly destroy” the Nephites specifically “because of their unbelief” in the face of all of the miracles and all of the divine enlightenment that they have received (cf. Alma 10:19-24). In other words, Nephite civilization would meet its final end with the Nephites in “unbelief” (cf. lōʾ-ʾēmun, Deuteronomy 32:20). Samuel concludes with an oath formula averring the reality of his prophecy.

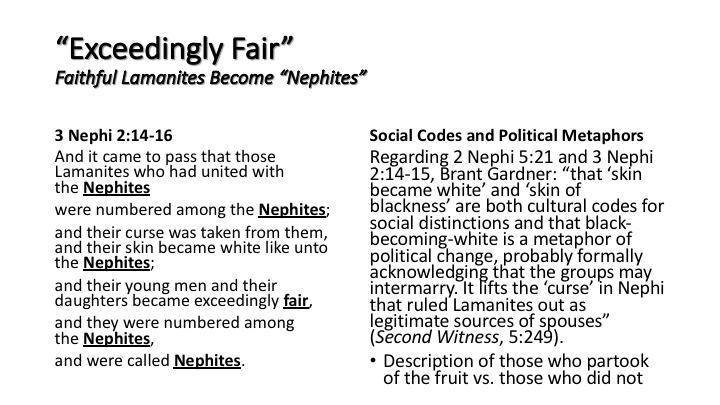

“Exceedingly Fair”: Faithful Lamanites Become “Nephites”

In his longer abridged Book of Nephi (later designated 3rd Nephi), prior to Christ’s appearance among “the people of Nephi” and “those which had been called Lamanites” (3 Nephi 10:18), Mormon detailed sociological change that many Latter-day Saints have traditionally interpreted as racial Lamanites being miraculous changed to racial Nephites:

And it came to pass that those Lamanites who had united with the Nephites

were numbered among the Nephites.

And their curse was taken from them.

And their skin became white like unto the Nephites.

And their young men and their daughters became exceedingly fair.

And they were numbered among the Nephites.

and were called Nephites. (3 Nephi 2:14-16)

Regarding 2 Nephi 5:21 and 3 Nephi 2:14-15, Brant Gardner rightly concludes, “that ‘skin became white’ and ‘skin of blackness’ are both cultural codes for social distinctions and that black-becoming-white is a metaphor of political change, probably formally acknowledging that the groups may intermarry. It lifts the ‘curse’ in Nephi that ruled Lamanites out as legitimate sources of spouses.”[83] Or put another way, Mormon is here describing a political, religious, and social conversion—not racial change. The term “fair” at the end of the clause “their young men and their daughters became exceedingly fair” occurs in an antistrophe or epistrophe spanning 3 Nephi 2:14-16. Lanham defines as antistrophe/epistrophe as “the repetition of a closing word or words at the end of several (usually successive) clauses, sentences, or verses.”[84] This repetition forcefully stresses the equation of the name Nephites with ‘fair’ ones.

Here again we hear echoes of the language of Nephi’s vision of the tree of life, which describes the tree as “white” and “beautiful” and the virgin associated with it as ’”white” and “fair” like the Gentiles and Nephi’s people who “who partake of the fruit are made white through the blood of the lamb.”[85] Rather than describing some miraculous change of race or ethnicity, Mormon describes religious, political, and cultural conversion in social codes derived from Nephi’s vision of the tree of life and Nephi’s own name (Egyptian ‘good, fair’).

Moreover, Mormon here sets the narrative stage for establishing the faithful Lamanites as the last bastion of the church prior to Christ’s appearance at the temple in Bountiful: “the church was broken up in all the land save it were among a few of the Lamanites which were converted unto the true faith; and they would not depart from it, for they were firm, and steadfast, and immovable, willing with all diligence to keep the commandments of the Lord” (3 Nephi 6:14). It comes, then, as no surprise Mormon’s audience to learn that those to whom Jesus appeared at the temple in Bountiful included a large number of “those which had been called Lamanites” (3 Nephi 10:18). Perhaps the most important endorsement of Lamanite faith and faithfulness comes from the voice of Christ: “And whoso cometh unto me with a broken heart and a contrite spirit, him will I baptize with fire and with the Holy Ghost, even as the Lamanites because of their faith in me at the time of their conversion were baptized with fire and with the Holy Ghost—and they knew it not” (3 Nephi 9:20).

The appearance and ministry of the Lord Jesus Christ to the Lamanites and Nephites functionally erased them as meaningful distinctions. Mormon plays on the meaning of the name Nephi when he remarks, “And now, behold, it came to pass that the people of Nephi did wax strong, and did multiply exceedingly fast, and became an exceedingly fair and delightsome people” (4 Nephi 1:10). “They were all … partakers of the heavenly gift” (4 Nephi 1:3) or partakers of the tree of life. He further notes a further blurring of earlier distinctions: “neither were there Lamanites, nor any manner of ites; but they were in one, the children of Christ and heirs to the kingdom of God” (4 Nephi 1:17).

When the old tribal distinctions reemerge (see 4 Nephi 1:36-39), it is not clear that they did so on any basis of race. The key words are again “believe,” “unbelief,” “not believe,” and Jesus Christ. Mormon remarks that “those who rejected the gospel were called Lamanites, and Lemuelites, and Ishmaelites” and that these neo-Lamanites “did not [merely] dwindle in unbelief, but they did willfully rebel against the gospel of Christ. And they did teach their children that they should not believe, even as their fathers, from the beginning did dwindle” (4 Nephi 1:39). Rejection of Christ and a lack of covenant faithfulness (ʾĕmûnâ) made one a “Lamanite.” They would not even commence in the covenant path toward the tree of life.

Moroni indicates that unbelief in Christ even became a kind of shibboleth: “because of their hatred they put to death every Nephite that will not deny the Christ. And I Moroni will not deny the Christ” (Moroni 1:2-3). Moroni groups the Lamanites and the Nephites who survived by abandoning their covenant faithfulness to Christ together thus: “And now after that they have all dwindled in unbelief and there is none save it be the Lamanites—and they have rejected the gospel of Christ” (Ether 4:3). All survivors at this point, including former “Nephites,” refused to partake of the fruit of the tree of life—Jesus Christ and his atonement— and all had become “Lamanites” regardless of any ethnic considerations.

This reality informed the writing of both Mormon and Moroni when they gave late statements of their purpose in writing: “And also that the seed of this people may more fully believe his gospel, which shall go forth unto them from the Gentiles. For this people shall be scattered and shall become a dark, a filthy, and a loathsome people, beyond the description of that which ever hath been amongst us, yea, even that which hath been among the Lamanites—and this because of their unbelief and idolatry” (Mormon 5:15). Here again, the key terms are believe (cf. Heb. heʾĕmînû/yaʾămînû), Lamanites, and unbelief (cf. lōʾ-ʾēmun, Deuteronomy 32:20). “Believing” (ʾmn) or “faith” (ʾĕmûnâ) is both the beginning of the covenant path and the “steadfastness in Christ” (2 Nephi 3::20). Lamanites during Mormon’s time describes all those who have willfully refused this path. Mormon specifically quotes Nephi’s small plates account of his tree of life vision and the description there of the descendants of the Nephites and Lamanites, who like Laman and Lemuel, were unwilling to partake of the fruit of the tree of life: “I beheld that after they had dwindled in unbelief, they became a dark and loathsome and a filthy people” (1 Nephi 12:23). As noted above, descriptions of “a dark, a filthy, and a loathsome people” or “a dark and loathsome and a filthy people” are to be connected—rather than to race, genetics, or ethnicity—to the filthy water and the “mist[s] of darkness” of Nephi’s vision or “the symbols of hell”[86] symptomatic of “unbelief.”

Moroni, for his part, makes two statements of purpose in writing that bear on this issue. First, he declares: “And these things are written that we may rid our garments of the blood of our brethren, which have dwindled in unbelief” (Mormon 9:35). Moroni knows that his latter-day audience, which would include the descendants of those who had “dwindled in unbelief” would to “believe” his and his father’s record in order have his Spirit to “persuade” them “to do good” (Ether 4:11), which brings them to Jesus Christ: “And whatsoever thing persuadeth men to do good is of me” (Ether 4:12). These statements deliberately quote or allude to 2 Nephi 33:4 (“it [Nephi’s record] persuadeth them [Nephi’s people] to do good”) and 2 Nephi 33:10 (“they teach all men that they should do good”), both playing on the name Nephi. Moroni offers another statement of purpose in writing that quotes Nephi’s words in 2 Nephi 33:10, 14. Notably, Moroni frames it in terms of the imagery of Nephi’s tree of life vision: “I Moroni am commanded to write these things, that evil may be done away and that the time may come that Satan may have no power upon the hearts of the children of men, but that they may be persuaded to do good continually, that they may come unto the fountain of all righteousness and be saved” (Ether 8:26).

Finally, unmoored from the traditional reading of white and “fair” as racial descriptions, we are prepared to appreciate the power Moroni’s invitation as an invitation to come to Jesus Christ, the tree of Life and to partake of its pure, fair, and white fruit: “O then ye unbelieving [i.e., those who have dwindled in unbelief, lōʾ-ʾēmun], turn ye unto the Lord; cry mightily unto the Father in the name of Jesus, that perhaps ye may be found spotless, pure, fair [cf. Nephi < nfr], and white, having been cleansed by the blood of the Lamb, at that great and last day. (Mormon 9:6). Once again, “he inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness. And he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female” because “all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile” and all can become and do “good” through Christ’s atonement.

Conclusion

Nephi and his successors understood the name Nephi in terms of its evident Egyptian etymological meaning—“good,” “goodly,” or “fair.” Ample textual evidence suggests that the Nephites understood and used the derived gentilic term “Nephites” in the sense “good” or “fair ones.” This understanding, in conjunction with the related concept of those partaking of the fruit of the tree as “fair” in Nephi’s vision, profoundly shaped Nephite self-understanding, and the application of “Nephites” as a religious, political, and social descriptor.

Moreover, an abundance of textual evidence suggests that the Nephites pejoratively treated the name Laman in terms of the similar sounding Hebrew expression lōʾ-ʾēmun (“no faith,” “unbelief,” Deuteronomy 32:20) and negations of the verb ʾmn (lōʾ + forms of ʾmn). This pejorative association also has roots in Nephi’s vision of the tree of life and the description of those who, like Laman and Lemuel, did not partake of the fruit as those who “dwindled in unbelief” (1 Nephi 12:22-23). A major focus of Mormon’s abridged narrative is to show how the Lamanites, whose conversion began with the efforts of Ammon (“faithful”) and his brethren, came to embody covenant faithfulness—ʾĕmûnâ.

In view of all of the foregoing, “Nephites” and “Lamanites” functioned as primarily religious descriptors of those who believed or disbelieved in Nephite religious traditions, especially those pertaining to the Messiah—those who partook of the fruit of the tree of life versus those who did not and would not. They also originally described political affiliation and loyalty and constituted general descriptors of lived culture. This has important implications for how we read passages like 1 Nephi 12:22-23; 2 Nephi 5:21-22; Jacob 3:3-11; Alma 3:4-19; and 3 Nephi 2:14-16, which are sometimes assumed to be merely describing some type of divine genetic reengineering. We do far better, in my view, to see these passages and the social codes they employ as reflecting Nephite self-understanding rooted in Nephi’s vision of the tree of life.

[2] See, e.g., Hugh Nibley’s attempts to make sense of the Lehite onomasticon. Hugh W. Nibley, Since Cumorah, 168-172. Although we now have better explanations for many of the names for which Nibley offers proposals, he clearly took the onomastic evidence of the Book of Mormon seriously. Nibley writes, “The greatest bonanza any philologist could ask for in coming to grips with the Book of Mormon is the generous supply of proper names, West Semitic and Egyptian, which the author dumps in his lap.”

[3] See further Matthew L. Bowen “‘And There Wrestled a Man with Him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s Adaptations of the Onomastic Wordplay of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 151-160.

[4] Moshe Garsiel suggests that the name Judah originally connoted praised out of a feeling of gratitude” See Moshe Garsiel, Biblical Names: A Literary Study of Midrashic Derivations and Puns (trans. Phyllis Hackett; Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1991), 171. Leah’s “praising” Yahweh “out of a feeling of gratitude” becomes the basis for naming Judah in (Genesis 29:35). This meaning is later reflected in Jacob’s blessing upon Judah: “Judah [yĕhûdâ], thou art he whom thy brethren shall praise [yôdûkā or, “Judah—thou, thy brethren shall thank thee”]: thy hand [yādĕkā] shall be in the neck of thine enemies; thy father’s children shall bow down before thee” (Genesis 49:8). Clearly, this blessing does not merely apply to Judah but also to his descendants—i.e., that Judah’s descendants will be “praised” or “thanked.” This points to a distinct meaning for Judah’s gentilic derivative hayyĕhûdîm—Judahites or Jews. The idea of hayyĕhûdîm (or hayhûdîm) as “praised ones” or “thanked ones” underlies Paul’s wordplay on “Jew” and “praise” in Romans 2:29. N.T. Wright, Paul in Fresh Perspective (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 118.

[5] See Matthew L. Bowen, “According to All that You Demanded” (Deut 18:16): The Literary Use of Names and Leitworte as Antimonarchic Polemic in the Deuteronomistic History (Ph.D. Dissertation; Washington, DC: Catholic University, 2014).

[6] Michael P. O’Connor, “The Human Characters’ Names in the Ugaritic Poems: Onomastic Eccentricity in Bronze-Age West Semitic and the Name Daniel in Particular,” in Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and Historical Perspectives, ed. Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2006), 270.

[7] Hugh W. Nibley, Since Cumorah. 2nd ed. (The Collected Work of Hugh Nibley 7; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 216.

[8] John Gee, “A Note on the Name Nephi,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1/1 (1992): 189-91. On why nfr is much more plausible than other suggestions, see idem, “Four Suggestions on the Origin of the Name Nephi,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 1-5.

[9] Apart from its extremely numerous attestations as an onomastic element in longer Egyptian names, it also occurred as a personal name by itself. Hermann Ranke (Die ägyptischen Personennamen [Glückstadt, Augustin, 1935], 1:194) cites numerous examples.

[10] Gee, “A Note on the Name Nephi,” 191.

[11] Gee, “Four Suggestions,” 2.

[12] Raymond O. Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1999), 131-32. See also Adolf Erman and Hermann Grapow, Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1971), 2:252–63.

[13] Matthew L. Bowen, “Internal Textual Evidence for the Egyptian Origin of Nephi’s Name,” Insights 21/11 (2001): 2; idem, “‘O Ye Fair Ones’: An Additional Note on the Meaning of the Name Nephi,” Insights 23/6 (2003): 2; idem, “Nephi’s Good Inclusio,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 17 (2016): 181-95; idem, “’O Ye Fair Ones’ — Revisited,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 20 (2016): 315–344

[14] All Book of Mormon citations follow Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

[15] Kevin Barney, “What’s in a Name? Playing in the Onomastic Sandbox” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 29 (2018): 251-272.

[16] See also John Gee, “Born of Wealthy Parents?” Forn Spǫll Fira: The Ancient Tale of Man (blog entry, June 23, 2014) http://fornspollfira.blogspot.com/2014/06/born-of-wealthy-parents.html (retrieved July 17, 2019). Gee cites glosses the Webster’s 1828 dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary none of which include the notion of “wealthy.” He concludes, “So, in Joseph Smith’s day, goodly did not mean wealthy. Yes, Lehi was wealthy but Nephi does not seem to be addressing that issue in his first verse, at least not based on English usage.”

[17] See Bowen, “Nephi’s Good Inclusio,” 183-184 note 6.

[18] See Matthew L. Bowen “Wordplay on the Name ‘Enos,’” Insights 26/3 (2006): 2.

[19] Matthew L. Bowen, “‘He Is a Good Man’: The Fulfillment of Helaman 5:6–7 in Helaman 8:7 and 11:18–19,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 17 (2016): 167-168.

[20] See, e.g., Daniel Belnap, “‘Even as Our Father Lehi Saw’: Lehi’s Dream as Nephite Cultural Narrative,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision (2011 Sperry Symposium), ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley A. Johnson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 214–39; idem, “There Arose A Mist of Darkness” in Third Nephi: An Incomparable Scripture, ed. Andrew C. Skinner and Gaye Strathearn (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2012), 75-106.

[21] Amy Easton-Flake, “Lehi’s Dream as a Template for Understanding Each Act of Nephi’s Vision,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision (2011 Sperry Symposium), ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley A. Johnson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 189.

[22] Ibid. Easton-Flake writes: “When one looks at the prophetic revelation through the lens of Lehi’s dream, it also become apparent that the individuals who possess this New World have partaken of the fruit of the tree in the course of their journey. The description of the New World inhabitants as ‘white, and exceedingly fair and beautiful” is one indication of this (v. 15).”

[23] Bowen, “Nephi’s Good Inclusio,” 189; Eve Koller (“An Egyptian Linguistic Component in Book of Mormon Names,” BYU Studies 57/4 [2019]: 139-148) makes an excellent case for the onomastic component ze– in Nephite names as the Egyptian z3/s3.

[24] Brant Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Textual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, Volume 3: Enos – Mosiah (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 228.

[26] Gardner, Second Witness, 3:350-351.

[27] Royal Skousen, Analysis of the Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, Part Three: Mosiah 17–Alma 20 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2006), 1605-1609.

[28] Brant Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, Volume Five: Helaman – 3 Nephi (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 126-127.