August 2019

I want to open with a few pithy and memorable statements.

Elder Maxwell once said that Latter-day Saints often “have a lack of doctrinal sophistication,” which creates problems. He actually used the word ‘gullible’.[1]

Sharon Eubank in General Conference a couple of years ago said that, “Each of us needs to be better at articulating the reasons for our faith.”[2]

And, attributed to Desmond Tutu: “There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.” We need to treat causes and not effects; not the symptoms, but the root issue.

And lastly, from Davis Bitton who said this at the FAIR conference 15 years ago, “What’s potentially damaging or challenging to faith depends entirely, I think, on one’s expectations and not necessarily the data. The problem is the incongruity between the expectation and the reality.”[3]

And so today, I wish to articulate in part the reason for my own continued faith in God, scripture, and the institutional Church. I will identify some common unsophisticated expectations about the nature of revelation, prophets, scripture, and Church leadership, which I think cause problems, and illustrate why those assumptions are not consistent with scripture or history.

This is BB Warfield, Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield. He was a staunch Calvinist, Presbyterian and a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary from 1887 until his death in 1921. Now, Princeton at the end of the 19th century was the center of Protestant thought; it was highly influential. It was also a battleground of Protestant thought.[4] Beyond having a magnificent academic beard, and I am jealous, I admit, because I can’t do that, Warfield contributed significantly to the theological foundations of the Fundamentalist movement of the early 20th Century, particularly regarding the concept of inerrancy.[5]

This is BB Warfield, Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield. He was a staunch Calvinist, Presbyterian and a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary from 1887 until his death in 1921. Now, Princeton at the end of the 19th century was the center of Protestant thought; it was highly influential. It was also a battleground of Protestant thought.[4] Beyond having a magnificent academic beard, and I am jealous, I admit, because I can’t do that, Warfield contributed significantly to the theological foundations of the Fundamentalist movement of the early 20th Century, particularly regarding the concept of inerrancy.[5]

Now, in spite of all that, Warfield thought that faith and scripture were compatible with biological evolution,[6] and he also made an argument for the presence of humanity in revealed scripture.[7] He argued against models of revelation in which prophets are mere conduits for the transmission of divine information or scribes of the divine, so-called “dictation” or “mechanical” theories of revelation.[8]

That is, he recognized that divine revelation comes through human means and thus bears human fingerprints. And he tried to balance and reconcile this with the divine. Now, BH Roberts said something similar about the balance between the human and the divine— “It is well nigh as dangerous to claim too much for the inspiration of God, in the affairs of men, as it is to claim too little”[9]— but I want to stick with Warfield for a minute.

I am not claiming Warfield as some kind of crypto-Mormon, far from it. Rather, I cite Warfield to make this point; If Warfield— a staunch Calvinist, proto-fundamentalist, quasi-inerrantist— could argue for the presence of the human in divine revelation, how much more should we Latter-day Saints recognize and try to understand the role of the human in revelation, scripture, and Church leadership? After all, in contrast to all those things about Warfield, our own leaders and canonized scriptures formally reject inerrancy.[10] The Book of Mormon title page states that it contains the “mistakes of men.” D&C includes instructions for excommunicating the President of the Church[11] and so on.

And yet many Latter-day Saints that I encounter are much more like fundamentalists. In fact, I think many LDS are like fundamentalist Protestants in that they transfer the need for absoluteness about the Bible onto a need for absoluteness with Church leadership. I keep a file of LDS statements I find in publications and on blogs and on Facebook to remind me that I am not creating a strawman here. Although I do not really have any data on how widespread these assumptions are, I do think that they are growing; there’s one LDS group pushing them that I find particularly dangerous, but I don’t want to name them. (See the Q&A below)

This is a conversation I had on Facebook with a fundamentalist evangelical. He really needed absoluteness for the Bible, and I pushed him on it a little bit with some humor.

This could have easily been a Latter-day Saint, swapping in “prophets” instead of “the Bible.” I have had LDS tell me, “if I can’t trust prophets absolutely, how can I trust them at all? If they don’t give us absolute knowledge, then what good are they?”

Now the problem with the term “fundamentalism” in an LDS context is that it’s kind of come to be associated with polygamy, and that’s not the kind of fundamentalism I’m talking about. So I’m going to use the terms “absolutism” and “absolutist” instead. For my purposes, I am defining this fundamentalism or absolutism with a couple of characteristics.

First, absolute consistency. This minimizes differences, tensions or contradictions in history or scripture as only imagined, misunderstood, or mistranslated. Often the word harmonize has been abused not to actually make harmony, but to make things sing in unison.

Second, absolute accuracy. That is, in this fundamentalist assumption, the idea is that revelation speaks primarily in historical and scientific terms[12] and is necessarily factually correct, because it comes from the mouth of God. This touches on the issue of recognizing different genres[13] in scripture, as well as inerrancy. Now, our teachers, our materials, most of us do not often talk about genre in scripture, and while we give lip service to errancy, in practice many of us are inerrantists.

The third assumption here is that revelation is absolutely unmediated. That is whatever human elements might exist in the revelatory process have no functional effect on the end result as it reaches us.[14]

As David Bentley Hart puts it,

Any coherent account of what [revelation] means must involve an acknowledgement that God speaks through human beings and all their historical, cultural and personal contingency. For [fundamentalists, however…] all the words of the Bible must be understood as direct locutions of God, passing through their human authors like sunlight through the clearest glass, and the canon of the New Testament… must be understood as a flawlessly immediate communication in its every historical and lexical detail.[15]

Once again, we could transpose this into an LDS setting in Gospel Doctrine class, and it would apply to a number of people in there. In other words, in this absolutist view, prophets would function like pure clear glass windows; they transmit revelation but have no effect on it at all, i.e.“prophets are just the medium; they’re the pipeline it comes through.”

And the last characteristic I would give for this absolutist approach to things is tends to be characterized by binary or polar rhetoric, which assumes clear bright line non-overlapping distinction between these things, e.g. “revealed/philosophies of men,” “correct/false,” “divine/apostate.” And this simple binary doesn’t reflect reality. I’ve made this argument at length elsewhere, and I’ll link to it when we get to the paper version.[16]

By contrast, what I want to argue today is that revelation is not absolute, but composite; that is, revelation will always have a significant human component, along with the divine. Now, two years ago at this podium I spoke about an idea called accommodation, the idea that God must adapt revelation down to the human condition in a variety of ways.[17] It has a lot of support in Christian and Jewish tradition and LDS doctrine and scripture and history. Today I want to speak about the other end of things. Accommodation is God doing the accommodating on his end. What I’m talking about today is, when the revelation comes to us, what happens? Once received by humans, it must be voiced, interpreted, understood, or implemented by us, humans.[18] The end result involves human input to a greater or lesser extent. So let me provide some examples of slightly different kinds, but all illustrating human influence on what we have received as inspired or revelatory. (I’m not really distinguishing between those two today.)

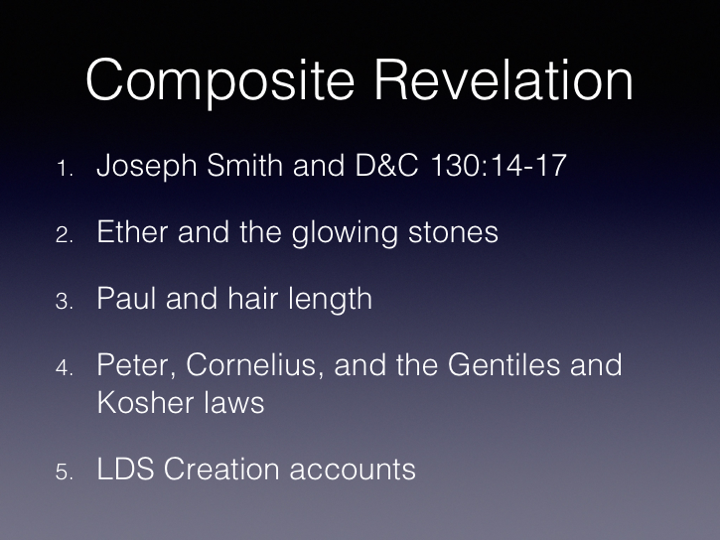

We’re going to go through five of these.

First, Joseph Smith Prophet of the Restoration. He once received a verbal revelation, now canonized in D&C 130:14-17.

I was once praying very earnestly to know the time of the coming of the Son of Man, when I heard a voice repeat the following:

“Joseph, my son, if thou livest until thou art eighty- five years old, thou shalt see the face of the Son of Man; therefore let this suffice, and trouble me no more on this matter.”

I was left thus, without being able to decide whether this coming referred to the beginning of the millennium or to some previous appearing, or whether I should die and thus see his face.

Now in this case, I suspect God was being deliberately vague, perhaps even tweaking Joseph a little to say, “you know, the second coming is not anytime soon and we have more important things at hand, so let’s table this.” But the point is, with this revelation, Joseph Smith was left to interpret it, to figure out what it meant, even though this was verbal, direct revelation from God. The point is, revelation is not self-interpreting, nor is its meaning always obvious. Once received, it has to be understood through human reason. It has to be interpreted. Its meanings and implications have to be teased out.

Second Example

In the Book of Ether, 2:22 onwards, we have the problem where they’re crossing the great ocean and it’s dark and the brother of Jared goes to the Lord and he says, “we’ve got this problem. What should we do for light?” And he receives revelation, which explicitly asks him for his human input, which may have surprised him. It’s a little bit like going to the big boss and saying, “you know, we’ve got a problem that’s above my pay grade. What do you want us to do about this?” And expecting to be kind of handed over a solution. And the big boss responds by saying, “well, here’s some options that won’t work, so what do you suggest?” Though miraculous, the resulting glowing stones involve both the literal hand of God and human ideas, human input, working together in tandem. The literal light of revelation in this case is the result of God implementing human input.

Example Three

Citing “nature itself,” Paul asserts a necessity for men to have short hair and women to have long hair in 1 Corinthians 11:13-15. We know now that Paul here is reflecting common Greco-Roman concepts of human physiology, which reasoned that hair length in the sexes contributed directly to fertility. This is a little bit weird and complicated to us, but there’s an entire article in the Journal of Biblical literature that I’ll link to.[19] Reproduction constituted the first commandment of the Bible (“multiply and fill the earth”), so Paul would have been attuned to this. In other words, men with long hair, less fertile; women with short hair, less fertile. So if you’re going to reproduce, you’ve got to have your hair the right way. This is an example of how the divinely-inspired canon includes culturally-influenced human ideas. Scripture thus comes to us not in purely divine form, but already pre-mingled with “philosophies of men.”

Now, a longer example. In the book of Acts (10:13ff), we find revelation that simultaneously undoes the kosher laws, which had been in force for at least a thousand years and opened to the Gospel to the Gentiles. These are monumentously massive religious, cultural and social changes with a lot of implications and a lot of associated questions. For such a large issue or two large issues, one might expect detailed instructions from the divine, but what do we find?

The revelation itself is short, even cryptically minimal. Peter sees a vision of un-kosher animals. And here’s a voice saying Peter, “arise, slaughter”—this is not just a verb “to kill an animal,” but this is the verb for ritually slaughtering an animal like you would at the temple—“Arise, slaughter and eat.” Peter resisted the revelation. “Not so Lord, surely not.” And the reply is “what God has made clean, you must not call profane or unclean,” and this is repeated three times. This is clear and unmistakable revelation, but there are no details. There is no mention of the Gentiles. Peter has to put this together with revelation to other people[20] as well as human logic and reason to figure out what it all means. And then there are all the implications. Do you need to follow the Jewish rituals and law to accept the Jewish Messiah? Yes. No? Somewhere in the middle? Some of them, but not all? What about circumcision? Had God changed the rules of salvation in the middle of the game? Do Gentiles who accept the Jewish Messiah born in Judaea and prophesied by the Jewish scriptures need to become… Jewish?

The apostles have to reason through all of this and the scriptures. The New Testament records that there are disagreements among Church leaders, sometimes sharp.[21] There are factions in different geographical churches and Paul spends much of his letters trying to work out and explain how all these things fit together. Look at the immediate aftermath in the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15, in verse 19. James says, “it is my judgment call that…” and then he kind of gives a ruling. He is not saying, “God has whispered to me.” He is not saying, “I have peeked into the divine Wikipedia, that this is how it eternally should be.” He says, “it’s my judgment call.” “This is what I think.” And he explains in Acts 15:28 a partial decision about what parts of the law need to be followed, and the language is very interesting. “It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us.” That is, “it seems good.” “It looks like the best option.” “It appears that this is what we should do,” and there is both human judgment in this—“It seems good to us”—and there appears to be some kind of spiritual confirmation that this is what they should do.

There is clearly divine and repeated revelation at the root of these massive changes about the kosher laws and the Gentiles. The end result, as the early Christians experienced it and scripture records it, involved a lot of people making a lot of humanly reasoned judgment calls and interpretations. Although it began with revelation, as perceived in the pew in Galatia or Corinth or Jerusalem it probably seemed like it had an awful lot of human aspects to it, maybe a “convenient” decision on the part of the Jerusalem leaders. They did their best to implement God’s will as it had come, as seemed best to them and the Spirit. I’m reminded of a comment by early LDS apostle Amasa Lyman, who, talking about polygamy, said, “We obeyed the best we knew how and no doubt made many crooked paths in our ignorance.”[22]

Now much more could be said about this example in Acts, with more passages brought to bear. Or we could profitably compare the differences between Kings and Chronicles, which tell the same stories differently, or the differences between the four Gospels.[23] But many LDS handwave away anything in the Bible that makes them uncomfortable or does not match the doctrinal status quo. Our “not translated correctly” escape clause is too easily used. It’s like a cheat code in a video game; It lets you bypass the hard stuff, which means you don’t have to do the work necessary to progress, and there’s no growth from having to wrestle through it.

Now, for my last and largest example, we’re going to move on to the LDS creation narratives. These come up an awful lot for me. Between my teaching, my work on Genesis chapter 1 (which is a book I’ve been working on forever), my dissertation work on biological evolution and Creationism, which deals with interpretations of Genesis and LDS scripture in general, I get asked about this stuff a lot.

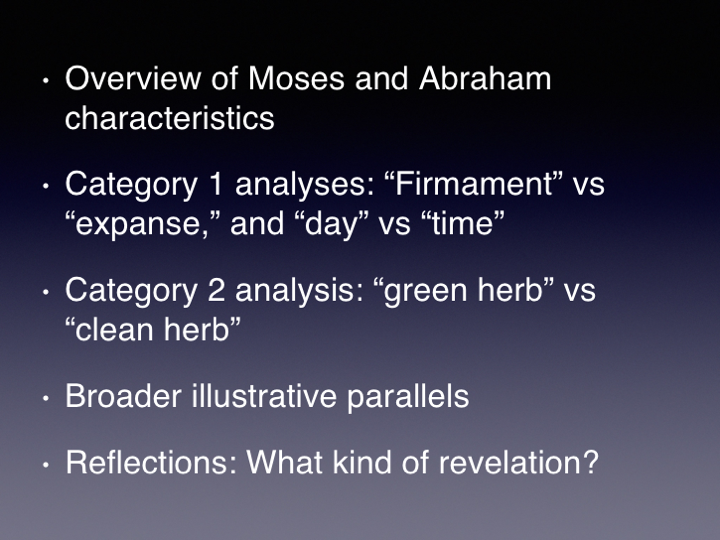

Joseph Smith brought forth three inspired revisions of Genesis, namely Moses, Abraham, and the temple. So two quick notes. First, I refrain from discussing the temple, although there are some really key things that would illustrate this point. So just keep in mind that there are some distinct and important differences. And second, I’m going to use “Genesis,” “Moses,” and “Abraham” throughout the rest of this, not to refer to those books as a whole, but just those chapters parallel to Genesis 1-3, for shorthand. My analysis is limited to those chapters. Differences between these Genesis parallels bear directly on how we conceive of revelation in the Church. And here, this is the one thing I’ll say about the temple, parroting Elder McConkie, there are some major differences in the temple in that the events are placed on distinctly different days.

“the Mosaic and Abrahamic accounts place the creative events on the same successive days…. The temple account… has a different division of events.”[24]

Now, how we respond to the differences between these creation accounts reveals our conception of revelation, and I believe these differences strongly undermine absolutist or fundamentalist conceptions of revelation. So I’m going to introduce two categories of differences between these texts. From an absolutist perspective, the revealed texts of Moses, Abraham and the temple should not have these differences. They should align identically against the “translated incorrectly” King James Version.

However, this is not what we find. So, in what I’m calling category one, the King James and Moses have the same text and then Abraham is different. Moses retains the King James language, but Abraham varies. And in category two, Moses makes a change, but then Abraham reverts back to the King James Version. From an absolutist perspective, both of these categories call the inspiration of Moses into question, just from different directions. Category one says, “Moses is not inspired enough.” Category two says it was mistaken to make a change in the first place. And, last note, the stark differences with the temple as referenced by Elder McConkie seem to call both Moses and Abraham into question.

I ask rhetorically, how can revelation be inconsistent or incorrect, particularly when coming through the same prophet in the same time period and culture? Doesn’t incorrectness or inconsistency completely undermine its claim to revelation?[25] Thus, textual issues generate theological issues, which quickly become pastoral/faith issues. I’d wager few people actually ask about the textual differences, but at the root, the problems here are interpretive assumptions about the nature of revelation, prophets and scripture. It’s apparent we need to wrestle with the nature of those a little bit more, as all too often the result for someone asking these questions is a rejection of the inspired nature of these texts, instead of a re-evaluation of the inherited assumptions that rejection was based on.

And so to give you a roadmap of where I’m going and the rest of my time, after a short review of Moses and Abraham, we’re going to look at two category-one examples, one category-two example, and then we’re going to zoom out to look at a couple that parallel those. And then I’ll conclude by offering some personal reflections on the nature of revelation as composite.

Moses

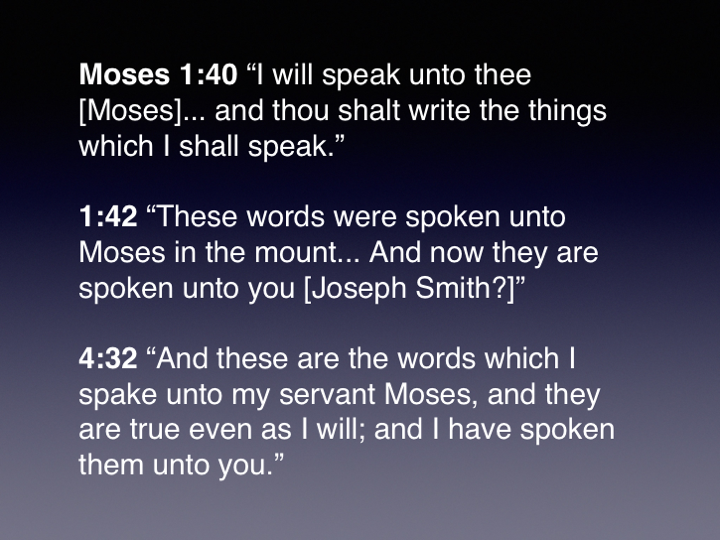

So let’s start with the Book of Moses. It is of course the Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis, and recognizing this raises certain questions and helps us avoid some assumptions. First, it means Moses does not constitute an entirely separate and independent revelation confirming Genesis. Rather, as with the JST, Joseph began with the English text of the King James Version and modified it. He did not start with a blank slate for God to write upon, which then happened to match Genesis. Second, in modifying and expanding the English language of the King James Version, Joseph did not make use of Greek, Hebrew or other translational tools to produce Moses. Third, some have read passages in Moses to indicate that Genesis was divinely dictated by God to Moses, and then apparently dictated to Joseph Smith again.

There are four major obstacles to that understanding. And of course, it is not impossible that God dictated revelation to someone. There are some examples in scripture where it seems like that would been the only option. I don’t think Nephi could have simply gotten revelation build a boat without some kind of revelatory Ikea instructions, because he was not a boat-maker. Ditto with King David and Solomon and the temple in Jerusalem. It says that they received a revelation with the taḇnīt (tavneet), the plan, the layout of the temple they are supposed to build.[26] But I think ultra-detailed revelation like that is the very rare exception and not the rule.

First off, Moses 1 originally was a separate and distinct document for Joseph Smith, which was later combined with the JST work after the fact, even though today it reads for us like a smooth blend from one into the other.

“The text now published as Moses 1 in the Pearl of Great Price… appears to have been originally produced as a separate and distinct document.”[27]

Second, in 1968 James Harris echoed Joseph Fielding Smith’s absolutist rhetoric that retention of the word firmament in Moses meant that it “reflects an apostate theology,”[28] and this would be the ancient Israelite “apostate” theology with the flat earth and a solid dome overhead and cosmic waters above and below.[29]

The idea that a text literally dictated by God would retain an “apostate theology” as they call it, seems difficult to justify from an absolutist perspective, particularly when it’s a one-word difference in a supposedly twice-dictated revelation.

Third, various characteristics of the JST itself and how Joseph Smith treated it argue against divine dictation. For example, Joseph translated the same passage twice with different results on several occasions.[30] Sometimes he provided a new translation, but later declared the King James Version correct. (See below) These militate against the idea of divine dictation to a prophet-scribe.[31]

Fourth, Robert J. Matthews, who was eminently orthodox, wrote a book on this and has been quoted in The Ensign multiple times to the effect that this was not simple scribal dictation from God, but a study and thought process, which implies that Joseph Smith’s thoughts are part and parcel of this. It was a revelatory process.

[the JST] was not a simple, mechanical recording of divine dictum, but rather a study-and-thought process accompanied and prompted by revelation from the Lord. That it was a revelatory process is evident from statements by the Prophet and others who were personally acquainted with the work.[32]

Now we have an explicit example of this “study and thought process” with the JST elsewhere. If we look at Hebrews 6:1, in Willard Richards’ account,

Heb 6th. contradictions “Leaving the principle of the doctrine of crist. if a man leave the principles of the doctrine of C. how can he be saved in the principles? a contradiction. I dont believe it. I will render it therefore not leaving the P. of the doctrin of crist.”[33]

So Joseph Smith read Hebrews 6 and said, in essence, “I simply don’t believe this as written. It’s wrong.” There’s no claim of revelation, no “the Spirit has whispered to me.” He’s reading it and going, “that’s not right. Let’s fix this.”

In other words, Joseph’s human cognition and interpretation are playing an active role in the text of the Joseph Smith Translation, which is what the book of Moses is. And we’ll come back to this later.

Now let’s assume against those four points that the book of Moses was dictated anyway. It does not follow from that such a divine dictation would be historical in nature. Taking scripture as our guide, revelation comes in parable, in poetry, historical fiction and fictionalized history.[34] Revelation is not itself a genre, but manifests itself in multiple forms and genres.[35]

In other words, accepting the inspiration of the literary narrative— which presents Genesis as a conversation with Moses— doesn’t dictate anything about whether it is actually a historical event or not, any more than Jesus saying, “A certain man went down to Jericho” indicates the actual existence of the mugged Israelite and empathetic Samaritan. Now I’ve had people who are not familiar with genre arguments come back to me and say, “are you saying Moses is a parable?” And I say, “no. I’m saying it’s not a journalistic history.”[36] I just use parables as my go-to example for genre because it’s the one genre people know the best out of scripture. And it’s clearly not a historical genre in nature, parables aren’t. But again, genre is rarely addressed in LDS treatments of scripture. So was the book of Moses dictated by God? It doesn’t seem so. More likely, it’s a literary framing, somewhat like the way the book of Deuteronomy updates and reframes the law of Moses, which I don’t have time to go into.

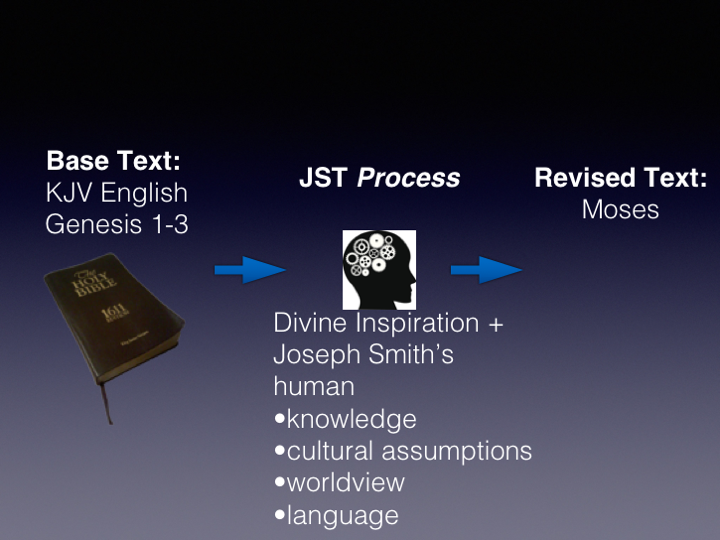

So this seems to be the process for the book of Moses. You start with the King James text that goes into what I’m calling the “JST process” in Joseph Smith’s head. It involves divine inspiration as well as Joseph’s human knowledge and cultural assumptions, his worldview, his English language.

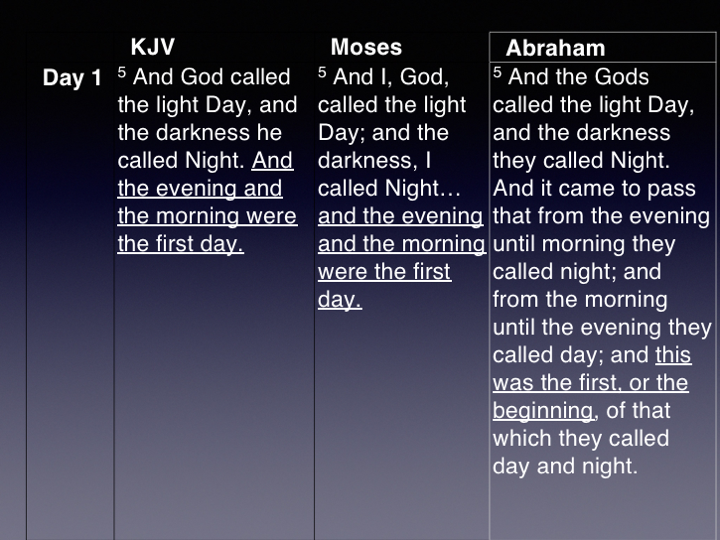

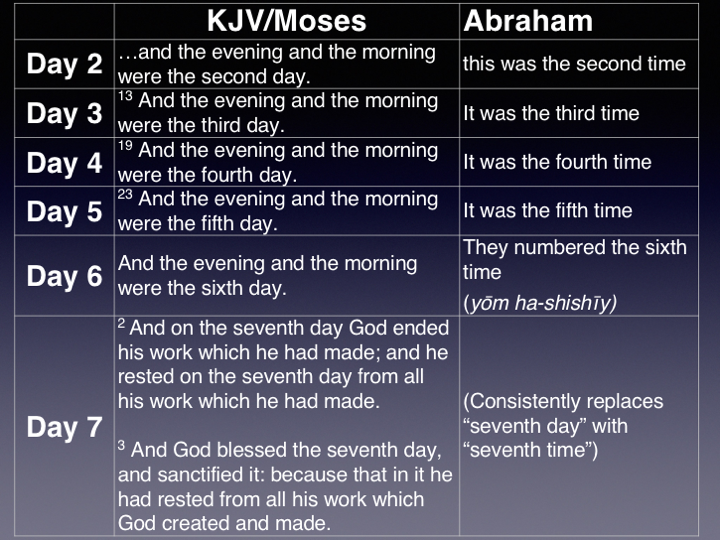

Now, as for the textual changes between Moses and the King James Version. Just looking at those two, they’re relatively minor. Mostly it’s a shift in person from the King James Version’s, “And God said x,” multiple times to, “And I, God,” [first person] “said x” multiple times. It’s in conjunction with Abraham and the temple that the text and changes in Moses become significant.

Abraham

So let’s talk about Abraham. Abraham is a very complex topic. Abraham’s a complex topic. I make no claim of expertise there and we’ll forbear on all but the most relevant and agreed upon details, which are that 1) Abraham, as a revelation brought forth by Joseph Smith postdates the book of Moses; 2) it postdates Joseph’s Hebrew studies. He acquired a number of lexicons and grammars and studied for several weeks under Josiah Seixas. And 3) lastly, a number of conservative LDS scholars have recognized the presence of Joseph Smith’s Hebrew in the Book of Abraham. It plays a role there.[37]

Now two things are significant about the presence of that Hebrew in the Book of Abraham. First, Hebrew as a Semitic language is out of place in Abraham’s location and time period in the Old Testament. We have good data on this. Hebrew did not even exist at the time; Abraham probably spoke some form of Akkadian or Amorite perhaps, but Hebrew simply hadn’t come into existence yet, not in his time, not in his place. So we should not expect it from a dictated perfect account from Abraham’s time period.

Moreover, the kind of Hebrew in the book of Abraham is distinct enough that it can be traced to Joseph Smith’s teacher’s materials.[38] Indeed, perhaps most of the category-one changes that I’m going to go into can be traced to Joseph’s Hebrew. We’ll see that the slide I used to illustrate the JST process with the book of Moses (above) seems to apply equally to the book of Abraham, the difference being the base text Joseph used. Whereas Moses came from Joseph Smith JST-ing English (to turn it into a verb), I think the Abraham parallels come from Joseph Smith JST-ing the Hebrew of Genesis 1-3. The process is the same, but the underlying text is different.

I think two related category-one examples illustrate this pretty clearly. They are “firmament vs expanse” and “day vs age.” I single these out because they indicate the influence of Joseph Smith’s Hebrew on Abraham in a way that only fits the modern time period from about the 1700s on down. Like any other language, biblical Hebrew changes and our understanding of the ancient world, the cosmology in Genesis and the meaning of corresponding Hebrew terms and concepts has changed since Joseph Smith’s day. So, let’s look at what I’m getting at here.

The first category-one change I want to talk about is the presence of the “day-age” interpretation in Abraham. The day-age interpretation, which you’re probably all familiar with, understands “day” in Genesis one as an indeterminate period of time, not a 24-hour day. The history here is important, because it shows how the day-age interpretation is a modern imposition on the text driven entirely by modern concerns. And the intellectual engine driving the day-age reading is a pervasive interpretation from about the last 600 years called “concordism.” This is the idea that scripture and science are inevitably saying the same thing because God is ultimately responsible for both, i.e. “God is responsible for nature and scripture, and as the author of both things, they should say the same thing. We just have to figure out how to make them mesh. They must be in concord with each other.”[39]

Read through a concordist lens, Genesis presents a physical or natural history of creation, even if in metaphorical or figurative language. Therefore, whatever Genesis says must match what science says. If the earth is old, Genesis must also be made to say the earth is old, and so the days of Genesis simply cannot be 24-hour days.

Now the “day-age” interpretation is not unique to LDS and predates the book of Abraham. It goes back at least French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1805[40] and some scholars push it back to Thomas Burnett in England in 1681, with his Sacred Theory of the Earth. In the 17th century, as various discoveries and understandings in geology and other fields began to indicate a very old earth, the controlling assumption of concordism steered the biblical interpretation to match. Burnett’s book was extremely popular. It had been imported to the US by 1689 and so the day-age interpretation arrived in the US very quickly and by the early 1800s it was an extremely popular way of making Genesis and science match up.

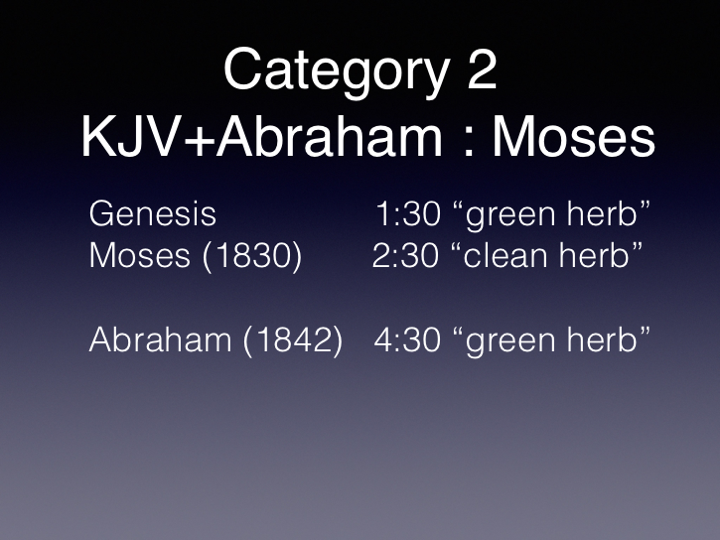

And what do we find in the Pearl of Great Price? The King James and Moses more or less say the same thing. And then Abraham on day one has a little bit longer verbiage. “This was the first or the beginning of that which they called day and night.” Moses matches the King James Version using day, but Abraham reads differently.

As we go onto the next days, the King James and Moses are identical throughout the days and on each one, the book of Abraham replaces day with the much more indeterminate noun, time.

Now, in the materials Joseph Smith used to study Hebrew from Josiah Seixas, that grammar book is only 32 pages long, and four-and-a-half pages of it are dedicated to a reprint of Genesis chapter one in Hebrew. We know Seixas taught with it. We know he made them read it. We know he used examples from it. Joseph’s Gibb’s Lexicon (1832) also defined yōm “day” as “time generally or a considerable time.” And so I strongly suspect that the translation in Abraham of time is a reflection of the day-age interpretation. Now, is the “day-age” interpretation of Genesis wrong? Let me bluntly say yes. Now the next question I immediately get is, “so we’re young Earth creationists?” And I say, “no, read my book that’s not out yet,” which is a cheat.[41]

The problem is that ancient creation accounts had very different purposes than recounting physical origins.[42] It’s not at all what Genesis is talking about.[43] It is our modern post-scientific-revolution, post-enlightenment assumptions (like concordism) that lead us to read Genesis for information about the physical origins of creation.[44] And that’s not the point Genesis was given for. It’s like reading the phone book for a recipe. It’s possible you can tease something out of it, but that’s not what it’s talking about when understood in context. Now my point is that Abraham here pretty clearly reflects what Joseph Smith was being taught in the 1800s about what the Hebrew meant.

So example two, Abraham changes firmament to expanse. In ancient Near Eastern cosmology, which was shared generally among the Israelites, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Hittites, the Moabites, the Ammonites, the Egyptians, pretty much everyone we have texts from who has written about this stuff, tells us that this is what the ancient Middle Eastern people believed about the cosmology. You had a flat earth with a solid dome above it. There were waters above and below that. And this was their conception of the universe. The firmament literally referred to that solid dome, which restrained the cosmic waters. That’s kind of an inverse snow-globe model; instead of this flat thing with the dome to keep the water in, God makes space within the watery cosmos, space for humans to live. So the inside of the dome has air and the outside is all cosmic waters. (I cannot recall where I got the image I use here, but there are many similar ones available.)

The translation expanse tries to get away from this well-established fact in order to align Genesis with science, because “we know that the sky is not a solid dome with waters behind it.”[45] Both Joseph’s 1832 Hebrew lexicon and Seixas grammar give the equivalent of raqia‘ as “expanse” instead of the more accurate “firmament.”

So the changes Joseph Smith makes that are unique to Abraham over against Moses and Genesis seem to have roots in the Hebrew of his day and in the understandings of 19th century Hebrew. The presence of these things in Abraham poses a problem for absolutist revelation.

So let’s look at category two. This is where Moses makes a change, but then Abraham reverts back to the King James Version.

“Green” and “clean” are similar words in English, and that may have been what triggered the change with Joseph Smith working with English for the book of Moses. But by the time he’s working on the book of Abraham, he’s studied Hebrew. And the Hebrew here in Genesis 1:30 is kol-yereq‘ēseḇ That is “every green thing, (namely) plants.” And so I propose that Joseph Smith made a change in Moses because “clean” made more sense than “green” plants. Not every plant is green and Jewish stuff makes sense with the idea of “clean.”

But once Joseph reads it in Hebrew, he says, “oh wait, I understand why the King James translated it this way,” and he reverts back to the King James reading. Again, it would seem that Joseph Smith’s 19th century human knowledge, which at this point includes Hebrew, is playing a role in how he is translating this and how we are encountering this revelation.

Broader Examples

Now if we look beyond the Pearl of Great Price, we find more category-two examples that may prove helpful. And these have also really bothered people who approach them with absolutist assumptions.

So first, we have Matthew and the Book of Mormon Sermon at the Temple reading the same way, but then Joseph Smith makes a change in the JST. Shouldn’t the JST and the Book of Mormon be the same, because they’re both inspired? We also find occasions where the King James Version and Joseph Smith agree against the Joseph Smith Translation.[46] In the Book of Revelation, Joseph made a minor deletion, but then in 1844 he quoted the King James and declared that it was “altogether correct in the translation.” In one of his last sermons in 1844 Joseph Smith gave a rendering of Genesis 1 as it read “originally,” which does not match Moses, Abraham, or the temple.[47]

Reflections on What Kind of Revelation

So what do we do with all this stuff? These differences between the texts themselves and examples from modern scripture undermine a simplistic equation of scripture with divinely revealed facts. They strongly suggest that revelation, ancient or modern, cannot be simplistically equated with “factual correctness.” Rather, we should understand revelation, even canonized modern revelation, as a process, a progression along a spectrum of correctness. Revelation is not static nor even a straight line of upwards progress, but a mediated human-divine dialectic process which sometimes becomes frozen as scripture. Think of scripture as an artifact or snapshot in time of the progress that is being made through revelation at a certain time, place, and context. Scripture thus contains human elements and understandings common to the time. And this can account for differences between inspired texts, which according to common assumptions should be identical. The textual differences in the Pearl of Great Price and the temple are best explained by conceptualizing revelation as a mediated human-divine composite process that incorporates human knowledge and assumptions of a particular time period and culture and time and place.

So returning to Davis Bitton, whom I quoted at the beginning, let’s ask, what kind of expectations about revelation and scripture and prophets and Church leadership are we creating with our children, with our grandchildren, with the youth we teach in Church, over the pulpit?

Henry Eyring Sr, the famous scientist, once cautioned that “Impetuous youth, upon finding the authority it trusts crumbling, even on unimportant details, is apt to lump everything together and throw the baby out with the bath.”[48] And I think we’re seeing that, to some extent, the more absolutist and fundamentalist the claim, and the tighter we link such a claim with the truth of the Gospel and the authority of Church leadership, the easier we make it to reject scripture and faith when that claim turns out to be more complex or have more humanity than people have been led to expect.

If the paradigm presented to me as a young believer or convert is a stark dichotomy between a human “man-made” uninspired Church and a fully-divine “inspired” one, completely lacking in human aspects, then any mark of humanity in that Church, scripture, or leadership moves me from one box into the other. Returning to BB Warfield, “on such a conception, it is easy to see that every discovery of a human trait in scripture is a disproving of divinity of scripture.”

In my view, too many LDS are raised with absolutist assumptions that prophets are mere conduits or windows that revelation comes through, that no human reason is involved in shaping, interpreting, understanding, or implementing revelation. Often they lose their faith, but they retain those absolutist assumptions.

To illustrate, here’s a meme that’s been floating around recently, and is supposed to be an argument against the truth of the Church. I did not make the cut, but you may recognize some people there.

Now what does this meme assume? If you have a prophet, you have an all-access on-demand VIP backstage-pass to the mind of God, which provides unmediated, unaccommodated, perfect knowledge. If you’ve got that, then no human reason should ever be necessary to understand, explain, or implement revelation. (Thus, the mere existence of apologists “disproves” the reality of prophets.) There is no room for humanity in that conception, but as I hope I have demonstrated, those assumptions about the nature of revelation, that it obviates any need for human reason, are not well-grounded. Now of course I am generalizing and I am pushing things a little bit to an extreme, but again, these assumptions are pretty broad among Latter-day Saints, and they come out in daily conversations and questions from students and Facebook posts all over the place.

My own assumptions and expectations have been fundamentally reshaped through my studies in history of religion, history of science, and the Bible. History of science, for example, is essentially the study of the nature of knowledge: what we know, how we came to know it, what it means to know something, and our assumptions that play a role in knowing. Our worldview, our way of thinking, our inherited assumptions, they seem just as reasonable and natural to us as the flat earth and solid domed sky was to ancient Israelites within their worldview and their inherited assumptions. This has made me aware that my inherited assumptions, in particular concordism, which I have written about elsewhere and I’ll link to, they’re not “natural” and neither are anyone else’s assumptions.[49] Assumptions are typically where the problem lies.

History of religion and Biblical studies have introduced me to non-LDS scholars wrestling with the nature of revelation in the Bible. For example, evangelical scholar Kenton Sparks and Jewish scholar Benjamin Sommer have each written books arguing that we should understand revelation as a human-divine collaboration. I am not really saying anything new or pioneering, from one perspective; I’m just bringing these ideas into an LDS setting here. Sparks in particular argues that revelation is progressive. That should sound familiar to us Latter-day Saints with our explicit doctrine we have of ‘line upon line’. The problem is that with our absolutist assumptions, we forget that doctrine and take any given line of revelation as ideal, static, absolute, and final instead of a temporary stopping place on the way to further updates, corrections or even reversals.[50] Latter-day Saint interpreters who engage in scientific concordist readings of the Pearl of Great Price, for example, want to take particular details as divinely-revealed scientific facts which are therefore unchanging and eternal, because “revelation comes direct and unmediated from the mind of God.” But because of the textual differences and their concordist assumptions, they have to take pains to pick and choose between different texts and accounts (Moses, Abraham, or the temple?) and how they relate those to the physical, natural history of creation that science has given us and is still discovering.

It is perhaps ironic that my relationship to the institutional Church and my faith are much more resilient because I expect that much of Church administration, hierarchy, and teaching is human. I believe God can and does speak to prophets, and I don’t think that belief is incompatible with the idea that the majority of day-to-day things that come from Church headquarters consists of humans doing the best they can with the revelation they receive, on the model of Acts 15:28; “it seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us.” I find that to be both realistic and believing, and it provides the title of my talk today. Paradoxically, it is by recognizing and understanding the presence of the human that my faith in the divine is preserved. Other LDS scholars have argued for the place of a human role in revelation. For example, Grant Underwood writes that

some Latter-day Saints may assume that the Prophet was not involved in any way whatsoever with the wording of the revelation texts, that he simply repeated word for word to describe what he heard God say to him. But our investigation has suggested otherwise. We need to see Joseph as more than a mere human fax machine through whom God communicated, finished revelation texts composed in heaven. Joseph had a role to play in the revelatory process.[51]

I would follow through on the logical expansion of that and say that today, Russell Nelson has a role to play in the revelatory process.

Revelation, scripture, and Church directives are not necessarily composed of divinely-revealed-and-ideal eternal facts, but inevitably contain human elements and understandings common to the time. Ultimately, the qualifying characteristic of revelation is not a complete lack of human aspects, but the guiding hand of the divine with that humanity, in a joint, composite, iterative and progressive process, which we call the Restoration.[52] Thank you.

Questions and Spontaneous Answers

Q1: How can I explain to others what you explained to us in a paragraph?

A1: I’ve been doing this for a long time, and… you simply can’t. I know there are a lot of people right now thinking about, how do we communicate particularly to young people, where podcasts and youtube videos are kind of becoming the default form of communication of information. And I suppose that for those of us who are more academic and wish to communicate down to the lay audience, we have work to do, to do that. I’ve written about a lot of this stuff and at this point in my writing, what I typically do when someone asks a question, as I say, “I’ve got 3000 words on this with a lot of references, please go give it a read or at least a skim and then come talk to me and let me know if that doesn’t help steer you differently.” A lot of these problems are not really about data. They’re about the worldview and the framework that we encounter the data in, the constellation of expectations that we have [i.e. Davis Bitton, whom I’ve quoted twice here.] I have quit responding online to particular questions about data and instead tried to work very proactively to shape that constellation of expectations, so that whatever the data is doesn’t trouble people, because there’s always more data coming. Brigham Young once said, [paraphrasing from memory] “The elders thought that all the cats were out of the bag, and then they heard about polygamy; brethren, you can expect an eternity of cats.” [Reference here, starting at the bottom of column 1] So I think the best thing to do is not try to explain particular issues, but to try to shape people’s worldview preemptively, so it’s capable of dealing with individual issues and data points.[53]

Q2: Please name the group pushing fundamentalism.

A2: There is a group that goes by the name the Heartlanders. They marry a particular geographic interpretation of the Book of Mormon (which is absolutely fine; you can think whatever you want about Book of Mormon geography) but they marry it with a right-wing constitutionalist politics, young Earth creationism, and authoritarian view of prophets that is absolutely absolutist. It’s like “God said it, I believe it; that settles it.” And they claim that anyone who disagrees with them is apostate. They have taken to naming Church history employees and BYU professors who are “off base.” I think the Heartlanders are dangerous fundamentalists, bottom line.[54] [And I would add, they traffic in demonstrable forgeries, jingoistic politics equated with Gospel truth, bad scholarship, reject actual experts in genetics, biology, and scripture for their own pseudo-scientific claims about DNA, the Universal Model, etc. The Heartland movement is dangerous because it is fundamentalist, and substitutes shiny fool’s gold and theological twinkies for hard truth. It approaches scholarship with its lips, but denies the power thereof. It has very little support from actual LDS scholars with relevant expertise.]

Q3: Why is this revelatory process not more frequently shown and discussed in the decision-making process of current prophets and apostles?

A3: I don’t have access to that kind of inside information. I have come to [these ideas] through my own professional studies, which I don’t think anyone in the Quorum has done. They experience it as a practical matter. Why they have chosen to keep those internal discussions more internal, I couldn’t say, but if we do go back and read LDS history, if you look early 20th Century, you have apostolic disagreements that were being carried out in public, in newspapers and debates. And that seemed to have a fairly divisive effect on the Church. So on the one hand, keeping those things much more private preserves a sense of unity. On the other hand, everything has trade-offs. It also gives the idea that whatever decision comes, comes because it is purely divine, and this is it. So I’m speculating there.

Q4: Question on Adam and Eve.

A4: Last summer I was asked to do a guest lecture for Late Summer Honors in BYU’s biology department. They asked me to speak about what Genesis has to say about evolution. I was given three and a half hours and I went over, so I’m not going to tackle Adam and Eve here, but you can find an outline of that lecture on my blog. [I would add, check out these books, these, and these audio lecture series as well.]

Q5: If in Hebrew “yom” only means a 24-hour day, how do you deal with the following passages?

A5: Here’s the thing, words mean different things in context and you cannot transpose meaning willy-nilly from one context to another. And here I’m borrowing from John Walton’s brief but accessible argument where he says, you know, if my wife calls upstairs and says, “We need to go!” And I say, “Okay, just a second,” and four minutes later I come down, I cannot take that usage of “second” and transpose it onto, say, the Olympic timing committee for races. Yom in certain contexts can indeed be used idiomatically to refer to an indefinite period of time. But you cannot transfer that idiom into Genesis 1, because the context is not there. It’s the “illegitimate totality transfer,” as it’s called. [I may have misremembered the proper category of error, but the term comes from the very useful book Exegetical Fallacies, which details common errors made in interpreting scripture.]

References and Notes

[1] “It never ceases to amaze me how gullible the Latter-day Saints can be. Our lack of doctrinal sophistication makes us an easy prey for such fads.” As quoted in Ryan Morgenegg, “Five Ways to Detect and Avoid Doctrinal Deception” Church News 17 September, 2013. Elder Delbert Stapley once remarked “the Saints are suckers.” As quoted in Stephen Robinson, Following Christ: The Parable of the Divers and More Good News (Deseret Book, 1995), 105-6.

[2] “Turn on Your Light,” October 2017 General Conference.

[3] Bitton, “I Don’t Have a Testimony of the History of the Church,” 2004 FAIR Conference. This presentation has been printed in several places.

[4] Bradley J. Longfield, The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates (Oxford University Press, 1993). C.f. Bradley J. Gundlach, Process and Providence: The Evolution Question at Princeton, 1845-1929 (Eerdmans, 2013)

[5] See the three works by George Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 2nd ed (Oxford Press, 2006); Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Eerdmans, 1990); Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism (Eerdmans, 1987).

[6] David Livingstone and Mark Noll, “B.B. Warfield (1851-1921): A Biblical Inerrantist as Evolutionist,” Isis 91:2 (June 2000), 283-304.

[7] Warfield, “The Divine and Human in the Bible,” Presbyterian Journal, May 3, 1894. Reprinted with analysis in Noll & Livingstone, eds., BB Warfield Evolution, Science, and Scripture: Selected Writings (Baker, 2000)

[8] More on this from an LDS perspective below, but see also my post here for a collection of LDS statements against taking “dictation” as the default form of revelation. See also ft 14 below.

[9] Roberts, Defense of the Faith and the Saints vol 1 (Deseret News, 1907), 527. Link

[10] References are too many to list, but e.g. Elder Uchtdorf’s recent statement that “there have been times when members or leaders in the Church have simply made mistakes. There may have been things said or done that were not in harmony with our values, principles, or doctrine.” I think the framework of “prophets can make mistakes” is not ideal, but still gestures in the right direction.

[11] D&C 107:82-4. See the procedural commentary by LDS lawyer and blogger Nathan Oman here.

[12] This assumption is essentially concordism, which I discuss further below. See the video of my UVU 2017 presentation “The Scientific Deformation and Reformation of Genesis,” summary and sources here, and an essay at Biologos.

[13] On genre, see my interview with LDS Perspectives here, a follow-up with some sources, and my many posts addressing genre in specific and general terms here.

[14] This assumption is sometimes called historicism. Grant Wacker writes, “conservative Protestant thinkers sculpted the cornerstone of orthodox rationalism by insisting that saving knowledge of divine things had been given to human beings directly, unmediated and uncontaminated by the historical context in which it was received. This presupposed of course, that the biblical writers had been essentially ahistorical figures, enabled by the Holy Spirit to transcend their social and cultural settings in order to articulate truths of timeless and universal validity. This meant that revelation was subject to clarification but not real development. Indeed, the conviction that God’s self-revelation has not been significantly shaped by the particularities of time and place has been one of the most prominent features of conservative Protestant ideology from the 1920s to the present.” Augustus H. Strong and the Dilemma of Historical Consciousness (Mercer University Press, 2005), 11. George Marsden similarly writes of some who “acknowledged that Scripture possessed a human as well as a divine character and they consistently denied mechanical dictation theories of inspiration. But the supernatural element was so essential to their view of Scripture, and the natural so incidental, that their view would have been little different had they considered the authors of Scripture to be simply secretaries.” Fundamentalism and American Culture, 2nd ed. (Oxford Press, 2006), 56.

[15] Hart, The New Testament: A Translation (Yale University Press, 2017), 575

[16] My paper from the 2017 Maxwell Institute Summer Seminar, “Mormonism as Rough Stone Rolling: Towards a Theology of Encountering the World.” Due to web changes at the MI, Summer Seminar papers are not currently available there. A copy can be downloaded from https://www.dropbox.com/s/0hf74ne5qb21ht0/Mormonism%20as%20Rough%20Stone%20Rolling.pdf?dl=0

[17] I have also spoken about accommodation in context of 1 Corinthians, at BYU’s New Testament Commentary Conference, “Christian Accommodation at Corinth,” video here.

[18] E.g. Elder Stephen L. Richards addressing BYU Students here, said

“Even under the assumption that Divinity may manifest to the prophet higher and more exalted truths than he has ever before known and unfold to his spiritual eyes visions of the past, forecasts of the future and circumstances of the utmost novelty, how will the inspired man interpret? Manifestly, I think, in the language he knows and in the terms of expression with which his knowledge and experience have made him familiar.”

More recently, see Eugene England in his excellent essay “Why the Church is as True as the Gospel,” says,

“Even after a revelation is received and expressed by a prophet, it has to be understood, taught, translated into other languages, and expressed in programs, manuals, sermons, and essays—in a word, interpreted. And that means that at least one more set of limitations of language and world-view enters in. I always find it perplexing when someone asks a teacher or speaker if what she is saying is the pure gospel or merely her own interpretation. Everything anyone says is essentially an interpretation. Even simply reading the scriptures to others involves interpretation, in choosing both what to read in a particular circumstance and how to read it (tone and emphasis). Beyond that point, anything we do becomes less and less ‘authoritative’ as we move into explication and application of the scriptures, that is, as we teach ‘the gospel.’

Yes, I know that the Holy Ghost can give strokes of pure intelligence to the speaker and bear witness of truth to the hearer. I have experienced both of these lovely, reassuring gifts. But such gifts, which guarantee the overall guidance of the Church in the way the Lord intends and provide guidance, often of a remarkably clear nature, to individuals, still do not override individuality and agency. They are not exempt from the limitations of human language and moral perception that the Lord describes in the passage quoted above, and thus they cannot impose universal acceptance and understanding.”

[19] Troy W. Martin, “Paul’s Argument from Nature for the Veil in 1 Corinthians 11:13-15: A Testicle Instead of a Head Covering,” Journal of Biblical Literature 123:1 (2004), 75-84. Summary at https://www.sbl- site.org/publications/article.aspx?ArticleId=271

[20] See the rest of Acts 10.

[21] E.g. Acts 15, Galatians 2.

[22] Journal of Discourses 11:207 (April 5, 1866)

[23] See e.g. my post here, introducing Seminary students to the idea of historiography, editorial shifts, etc. C.f. the very useful discussion of Samuel/Kings vs. Chronicles in Peter Enns, Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Baker Academic, 2005). Notably, the problems Enns finds among Evangelicals because of certain assumptions they make are also found strongly among LDS.

[24] Elder McConkie, “Christ and the Creation,” Ensign, June 1982.

[25] See my old post on “theological diversity” here.

[26] 1Chr 28:11, David gives Solomon the taḇnīt (KJV “pattern”) and the following verses explain parts of it. Then v. 19 says “All this, in writing at the Lord’s direction, he made clear to me—the plan [taḇnīt] of all the works.”

[27] Thomas Wayment, in Foundational Texts of Mormonism: Examining Major Early Sources (Oxford Press, 2018), 77.

[28] See Harris, “Changes in the Book of Moses and Their Implications Upon a Concept of Revelation,” BYU Studies 8:4 (1968). Also note that the PDF and text reflect a transpositional printing error in the original journal.

[29] This is well-established by Biblical and ancient Near Eastern scholars across theological boundaris, e.g. Kyle Greenwood, Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science (IVP Academic, 2015) See also my old posts here, here, and here. On the idea that God might make use of the ideas of the time, such as ancient “mythic” conceptions of the cosmos, see here, here, and here.

[30] Kent P. Jackson, Peter M. Jasinski “The Process of Inspired Translation: Two Passages Translated Twice in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible,” BYU Studies 42:2 (2003)

[31] For more citations on LDS and dictation theories, see my post here.

[32] Robert J. Matthews, quoted by David Rolph Seely in “The Joseph Smith Translation,” The Ensign (Aug 1997)

[33] Willard Richards account, 15 October 1843, p. 129.

[34] Indeed, as Robert Alter says, “History is far more intimately related to fiction than we have been accustomed to assume.”The Art of Biblical Narrative C.f. the discussion by John S. Tanner of fictio (the root of fiction), meaning “to shape, to fashion.” “Even factual writing inescapably entails fiction in the sense that it too must be fashioned (fictio); likewise, narrative history requires attention to the demands of a story. Hence, historical writing possesses not only the dimension of historicity but also of textuality, including qualities associated with literary texts.The same general point applies not only to history but to every scriptural genre, such as preaching, prophecy, poetry, and even parable.” Tanner, “The World and the Word: History, Literature, and Scripture” in Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 217–36.

[35] See part 4 of my Sperry Symposium presentation dealing with genre, here.

[36] “History to most modern Westerners is what happened in the past, and as a genre of literature it is an account of what happened in the past. We judge written history by how accurately and objectively it recounts past events. In other words, we tend to apply to history the same standards that we apply to journalism….We assume that ancient historians, and the biblical writers in particular, had the same definition of history. This assumption has been and continues to be the source of problems.”- McKenzie, How to Read the Bible: History, Prophecy, Literature— Why Modern Readers Need to Know the Difference and What it Means for Faith Today (Oxford Press, 2009), 25. See also my posts here and here.

[37] See e.g. Matthew J. Grey, “’The Word of the Lord in the Original’: Joseph Smith’s Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 249–302. C.f. his interview with LDS Perspectives podcast, here.

[38] That is, the Hebrew reflects Seixas’ Sephardic pronunciations and transliterations. See Matthew J. Grey, “’The Word of the Lord in the Original’: Joseph Smith’s Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 249–302.

[39] See the video of my UVU 2017 presentation “The Scientific Deformation and Reformation of Genesis,” summary and sources here, and an essay at Biologos.

[40]E.g. Jitse M. van der Meer, “Georges Cuvier And The Use Of Scripture In Geology” in Nature and Scripture in the Abrahamic Religions: 1700-Present, Vol. 1 (Brill, 2008), 119-120.

[41] See my old post here and comments.

[43] See John Walton’s suggestive thesis in The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate, which I review here.

[44] “It is not too much to see in all this a common preoccupation with the scientific method, scientific evidence, and scientific results, which descend upon these ancient pages [of Genesis] like a cloud of termites eager to devour and digest the materials in terms of their own appetites. This is not to debunk science or historiography as such. Rather, the issue is one of appropriateness. Our contemporary preoccupations could hardly have been the preoccupations of ancient Israel…. It is quite doubtful that these texts have waited in obscurity through the millennia for their hidden meanings to be revealed by modern science. It is at least a good possibility that the “real meaning” was understood by the authors themselves…. Charles Darwin, in comparing his observations of nature with the biblical accounts of creation, assumed that they were the same sort of statement and declared that the Old Testament offers a ‘manifestly false history of the earth.’ While religious objections have tended to focus on the word false, and many evolutionists—following Darwin—have been inclined to agree that it is false, the central issue is whether the biblical materials are being offered as a “history of the earth” in a sense comparable to the modern meaning of natural history. If they are not, then both the attempts at demonstrating their scientific falsity and the attempts at demonstrating their scientific truth are inappropriate and misleading.”- Conrad Hyers, The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science (John Knox Press, 1984), 3, 6.

[45] E.g. “Despite the NIV’s attempt to mitigate the meaning of this word in Genesis 1 through an ambiguous translation such as ‘expanse’ and the attempt of others to make it scientifically precise through the translation ‘atmosphere,’ Seely has amply demonstrated that, structurally speaking, the raqîa’ was perceived by the Israelite audience, as by nearly everyone else until modern times, as a solid dome (Seely 1991, 1992). This conclusion is not based on false etymologizing that extrapolates the meaning of the noun from its verbal forms (which have to do with beating something out) but on the comparison of the lexical data from OT usage of the noun with the cultural context of the ancient Near East.” -John Walton, Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch, “Creation”

[46] The language of “agreeing against” is common in textual criticism. See Ben Spackman, “Why Bible Translations Differ: A Guide for the Perplexed,” Religious Educator 15:1 (2014): 31–66.

[47] I.e. the so-called King Follett Discourse, beginning with “I shall comment on the very first sentence.” Joseph Smith Papers and introduction.

[48] Henry J. Eyring, Mormon Scientist: the Life and Faith of Henry Eyring (Deseret Book, 2008), 246.

[49] See the video of my UVU 2017 presentation “The Scientific Deformation and Reformation of Genesis,” summary and sources here, and an essay at Biologos.

[50] BYU Professor Dil Parkinson’s 2004 devotional “We have Received and We Need No More” addresses this issue quite well.

[51] “Relishing the Revisions: Joseph Smith and the Revelatory Process,” BYUI Devotional, Oct 13, 2009. My emphasis. Similar analysis from Underwood appears as “Revelation, Text, and Revision: Insight from the Book of Commandments and Revelations” BYU Studies 48:3 (2009)

[52] Elder Uchtdorf, “Sometimes we think of the Restoration of the gospel as something that is complete, already behind us—Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon, he received priesthood keys, the Church was organized. In reality, the Restoration is an ongoing process; we are living in it right now. It includes ‘all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal,’ and the ‘many great and important things’ that ‘He will yet reveal.’” “Are You Sleeping Through the Restoration?” April 2014 General Conference.

[53] E.g. see my posts here and here.

[54] See https://www.nevillenevilleland.com/2019/08/neville-misrepresents-fairmormon-conference-speakers.html This anonymous blogger tracks the Heartlander movement.

[This transcript has been edited for clarity and readability.]