August 2018

It’s a pleasure to be here and you might say there’s maybe some disconnect between working with historic sites of the Church and the title of my paper. And that is because there is a disconnect. What I’m talking about today happens to be my personal project, something I’ve worked on at night and on the weekends for the last six years, and that is a documentary edition of the letters of a 19th century Mormon woman who sent her husband off on four missions during the early years of their marriage. I’ve been working on this project with a friend named Beth Anderson, so I have to give her just due for this as well. And we’re in final edit, so we hope we’ll be sending it off to a publisher soon.

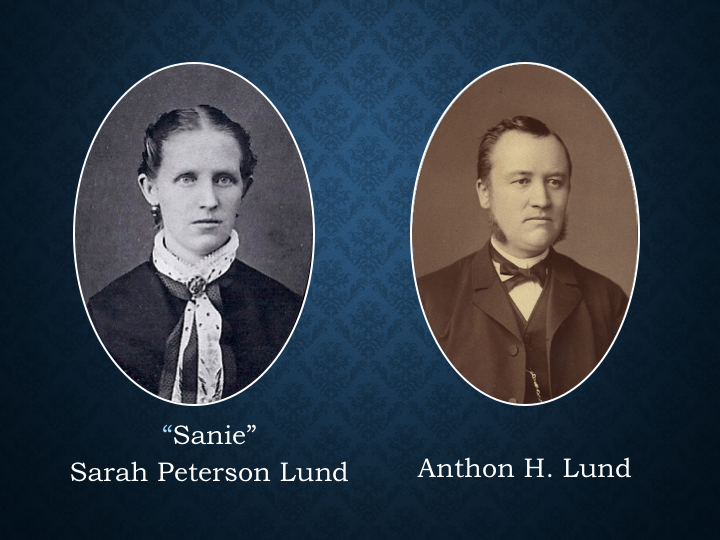

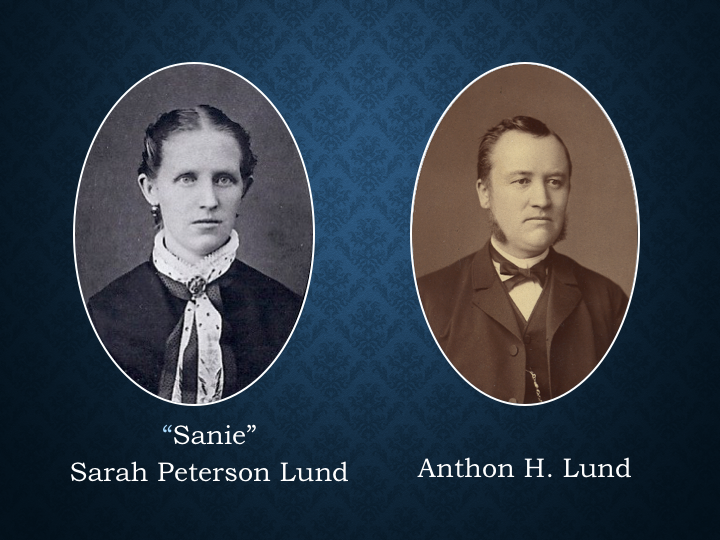

I hope I can do two things today, one of those to give you a sense of what it was like to be a missionary wife in the 19th century and what we can learn from those experiences, and then the second is to talk just a little bit about stories and coming to understand people. When you’re working with letters, you’re really dealing with fragments. You don’t get whole stories in the letters very often. Every once in a while you do, but they’re just kind of doled out week by week. You get a little bit here and a little bit there, but you can pull those together into some really fascinating stories. So let me introduce you to Sanie Lund.

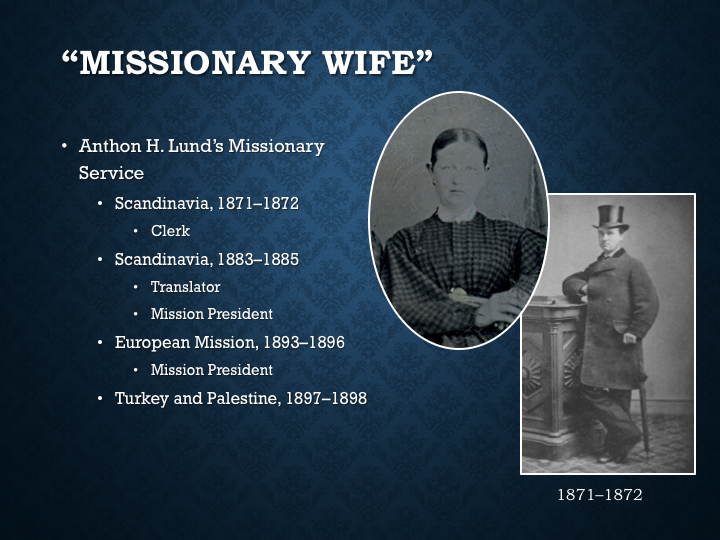

In the fall of 1883, Sanie sent her husband, Anthon H. Lund off to serve a mission. He was gone a total of 26 months, leaving her to manage the boys, the household and all their affairs alone. Sanie’s non-Mormon aunt from Illinois, on hearing this wrote, she thought it was “…the awfullest thing you would leave your wife and little children to go so far away,” Sanie reported to her husband. “She said we all must be crazy.” Perhaps not crazy, but certainly devoted to preaching the gospel in the 19th century. Anthon’s response in his diary says, “Take our religion out of the question and it would be an act I would not be guilty of, but as long as the Lord wants me here, I will try to do my duty.”

The reality was that most of the missionaries in the 19th century were married men. William Hughes found that among a sampling of missionaries called between 1849 and 1900, nearly 78 percent were married. It was not until the late 1880s that the trend began to shift towards single elders, finally reaching 50 percent between 1896 and 1900. Unlike Protestant missionaries, Mormon missionaries were not usually accompanied by their wives and children. The paradigm created a situation in which missionary wives were forced to assume the responsibilities that were somewhat similar to those of a widow, at least for a time.

In an introduction to a collection of articles exploring widowhood in the American southwest, Arlene Scandron delineates the challenges faced by widows, most of which can be applied on a temporary basis to the missionary wife: dealing with immediate grief of separation, new and usually reduced financial circumstances, responsibility for household, family and business affairs, loss of consortium, loneliness, isolation, and the need to forge a new identity, and new social networks as women alone. It is no surprise then the 20th century authors have sometimes written about Mormon missionary wives as “missionary widows” because of the similarities there.

Sanie Lund was perhaps was one of perhaps as many as 10,000 Mormon women who sent their husbands on missions in the 19th century. During the first 30 years of her marriage, her husband filled four missions and he was gone more than a total of seven years. Her experiences are detailed in a series of letters. There’s still extant one letter from 1872 when her husband was gone in Scandinavia; there are 92 letters written between 1883 and 1885 [he was again in Scandinavia]; and then there are 11 letters between 1893 and 1894, and that time he was in England serving as European mission president.

The value of these letters, however, transcends family history. They provide a lens through which to examine the impact of Mormon missionization on wives and children. Missions interrupted relationships, disrupted normative gender roles, created economic burdens, required extended family and community support, engendered uneven religiosity within a family, and required significant sacrifices on many fronts. The demands were so great in fact, that Sanie refers to herself on several occasions as a ‘missionary wife’ and to her responsibilities as a ‘mission’, as if she has her own distinctive calling in partnership with her husband, although she is quick to point out that she has all the work while he has all the honor.

Her letters are fabulous because of her unflinching candor. She tells everything like it is and she would refer to it as her saucy tongue. The letters are filled with town gossip. The time these letters were written, they lived in Ephraim, Utah in Sanpete County, and so she paints this unique portrait of daily life in town, and the people who inhabit it. It’s filled with great characters. My plan today is to share with you a series of those stories that illuminate the life of a missionary wife, focusing on the letters that were written between 1883 and 1885.

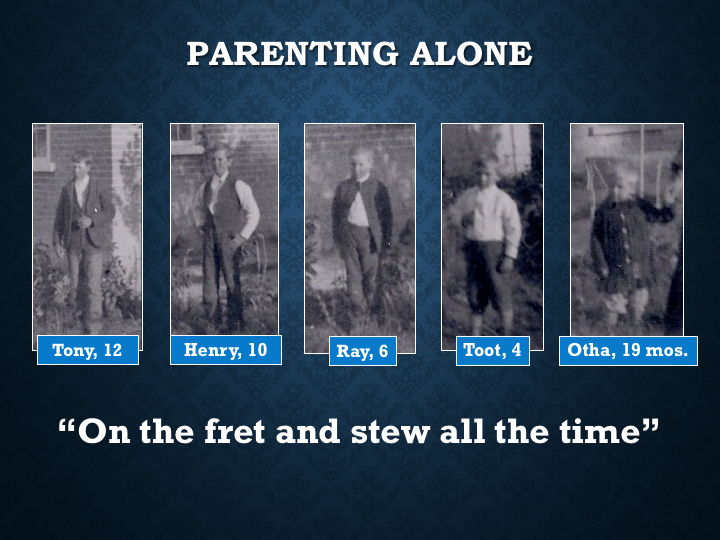

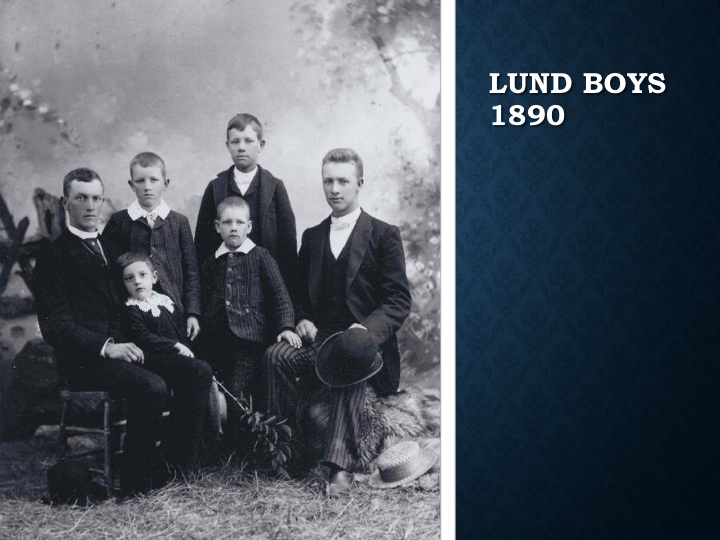

Sanie was left at home with five rambunctious boys, ranging from the oldest, Tony, who was 12 to Henry, Ray, Toot and Otha, the youngest who was just 19 months halfway through Anthon’s mission.

She describes the happenings that week: Otha fell on a pitchfork, running a tine into his head just above the eye, and Tony dislocated his finger. “It is, Anthon,” she bemoaned, “just enough to keep one on the fret and stew all the time.” With five boys in the house, including a toddler, there was a never a dull moment. Otha, the youngest, was particularly mischievous. Shortly after Anthon left, she took Otha, who was still nursing, to Sunday worship services at the Tabernacle.

“He kept talking and singing so loud that everybody around there could not help but notice him,” she recounted to her husband, “and to finish off with, he called as loud as he could, ‘Sanie, give me some titty now! Take it out, Sanie!’” She cringed. Continuing, “Then the folks all around laughed. I felt rather cheap.” It is no surprise that she hardly ever goes to church again during those 26 months that Anthon is away.

Tony, the oldest, at first was a big help. He did all kinds of things to shoulder chores and hired himself out to work, but then he begins to resist parental authority. He’s turning into what we today would call a teenager, and Sanie becomes more and more anxious. She writes, “Your boys need you to manage them. I hope for their sake you will not have to stay another winter.” The fact that Anthon was not there to correct the boys was vexing. He could send her all the advice in the world to be more firm, but as she noted, it is easier said than done. She expected Anthon to play a major role in disciplining the children, but his absence prevented that. “They really do need you to manage them and counsel them,” Sanie wrote in July 1884. “They get tired of mother’s talk. They need someone firmer to lead them along.” She worried they would run wild when school was out of session, picking up idle habits and ignoring their chores. She wrote, “I often wonder if you once think it is a care for me to be left alone to manage the children, or if you are too busy.” Then in a fit of pique, she exclaimed, “I often think you are needed just as bad at home as there. Let the sinners take care of themselves.”

Management of household finances was a challenge. Anthon had been the manager of the Ephraim United Order Co-op Store before he left, and so he had had regular income and was able to leave money on account in the store. They also owned shares in the store, so that meant there was a dividend coming in, and they were really better off than many, many missionary families where there was really just a farm to sustain the family scene. Sanie did not have to worry about farm work fortunately, but the kinds of things she did have to worry about were the kinds of things she’d never done before. Within weeks she’s writing Anthon, bemoaning the fact that the money goes so fast, “It is payout for every little thing,” she wrote, “and no way of making a cent.”

Later on her letters become even more anxious. She writes about dull times when it comes to economics. On this mission there was a major depression in the United States in 1884 and 1885. It was caused by a reduction in railroad expansion and then poor harvests and bank panic, and so she’s having a very difficult time even making things meet. She writes, “Trade is very dull. Money is scarce. Very little dividend, if any.” It was never easy to send a husband off on a mission, but those who did so during times of economic downturns faced particular challenges. She did that twice. Her husband was on a mission during two of the three major economic depressions in the United States in the 19th century.

Even when she knew he was coming home, she said, “I do not see what you can do to make anything. Times are so dull that there is not much to make.”

Everything rested on Sanie’s shoulders. “I feel so helpless sometimes,” she wrote, “Some women can make their living,” she asserted. “It would be a slim living I would have if I had to make it.” She did a number of things to make a living. She took in boarders. She raised pigs and chickens. She occasionally sold or horse or a cow. She refers in her letters to a job, and we have no clue what that job would be. It’s probably something she’s doing to just earn a little money on the side. Of course, like any rural family in that time she had a large garden which she took care of and orchards around the house which provided plenty of fruit and vegetables, and her oldest boys were old enough that they could hire out to her brothers or somebody else in town, or they would help her brothers cut hay on the meadow and bring in hay for the animals.

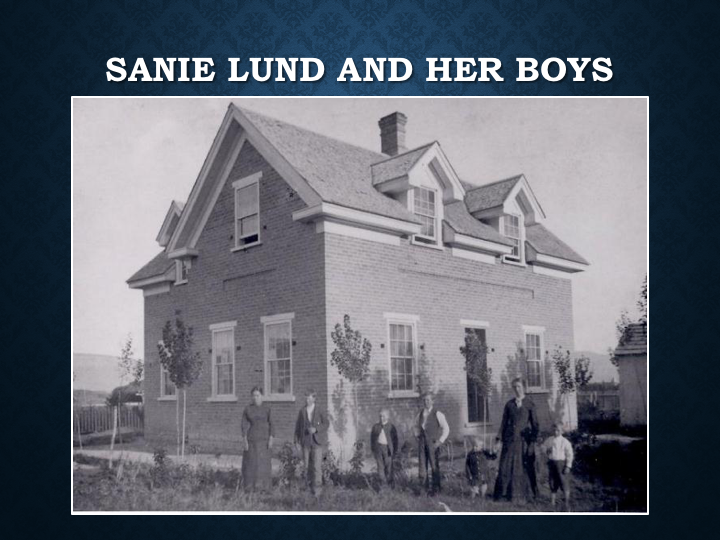

One thing that they were hampered by was that they didn’t have a barn, and she complains about how difficult it is, particularly in the winter, in the cold, to be out taking care of the animals. And so without consulting her husband, she bought logs and hired workmen and decided she was going to build a barn. She writes him with trepidation. She says, “I hardly dare tell you, I am having a little barn put up. The shed was not fit to stack hay on, and we suffered so with the cold last winter. I thought it would be best all around to have a little barn.” She noted, “It was not very costly,” and continued, “I hope you will not vexed about it, and I think I might use the means better. I am doing it for the best and hope you will think so too.”

Sanie’s barn was 30 feet long, 20 feet wide and 16 logs high. It held 15 loads of hay and stabled seven head of livestock. In the ensuing letters, she drops little hints week by week. She describes the barn as “…horrid pretty, but it keeps the hay dry and the cows warm and the boys are so glad we have got it, as it makes it much easier for them this winter, and the mornings are very cold.” As spring arrives, Sanie holding in her accomplishment, chided Anthon. “We would have saved money if we had built one years ago.” In the nine months between first mention of the barn and her teasing comment in April, her confidence in herself and her abilities grew significantly. She goes from timid to confident, and she crows about their good fortune. Why hadn’t Anthon thought about this years ago?

The barn represents the dilemma of missionary wives; missionary wives had to step into roles that they were uncomfortable with. Building a barn would have been considered the male sphere of work as well as most of the family finances. So many things that Sanie had to do in Anthon’s place. Now it’s not that women didn’t have economic interest because they did, and there are studies that show that women brought in between typically 45 and 50 percent of the household income in the mid 19th century, particularly in rural areas, but they didn’t have to be in charge of everything like she has to. The fact that women did play large roles in the economic sphere is one of the things which made the 19th century Mormon missionary enterprise possible. It’s because somebody was at home who would be able to take care of the family and support them economically with some help from the community, but not totally supported by the community. So men could leave for extended periods. Although Sanie complains about times being dull and bemoans, “The money goes so fast”, not once did she indicate they don’t have enough to eat. To the contrary, she notes, “We do not lack for what we really need. Have a good comfortable home and plenty in it to eat.”

Large scale farming was typically male work. And so her oldest son, sometimes the second son would hire out to carry on what little farming this particular family needed. And in all cases, the bishops were expected to look after the wives of missionaries in the communities. Some did that much more effectively than others did. And in Sanie’s case, the bishop was very attentive to her needs. She writes of Bishop Anderson, “During one visit he noticed there was such a mud hole in front of the gate. And this afternoon his boys came with a big load of gravel and fixed it.” However, sometimes she was also left to her own devices. “Now I must see to getting coal and wood for winter. I do hate this being man and woman both. It does not agree with me. I don’t like it, but I will have to like it or not another year.”

And then in a tirade of frustration, she writes, “Tomorrow it is one year since you left home. You say you are happy to be there because it is your duty to be there. Well, I suppose your duty is a pleasant one. It seems to be my duty to wait on sick children, but I can’t say I’m happy to do so. But you are free from care and anxiety. Well, I am loaded down with it in one form or another, and that makes the difference. I often wonder how President Lund would feel to be home nursing sick children one weekend out and another in, and his wife in Denmark enjoying herself. I don’t believe it would agree with his religion as well as the poses you now hold.” So Sanie never hints that she wants to enlarge her own sphere, but she is very aware of gender differences, gender discrepancies in status within her family and within the community, and the fact that she had all the work and worry at home constantly rankled her.

The letters are also imbued with a deep sense of anxiety about the specter of plural marriage, which constantly hangs over the house and the fear that her husband will bring home another wife from his mission. Now, this is Sanie, she’d be about 17 or 18 here when Anthon went on his first mission. She grew up in a plural household. So this is her father, Canute Peterson, and that’s her mother and his father’s two other wives. And the second of those wives, her father had met while he was a missionary and after he came home and she immigrated he married her within six weeks of her arrival. So this is not uncommon particularly. I looked at all the polygamous marriages in Ephraim and there are a lot of missionaries there who married someone that they met on their mission, so she has real reason to be concerned about this. Very few letters go by without a jab or two at Anthon over plural marriage. Sometimes these jabs are teasing, so referring to her brother Nels, who’s gone out courting, she says, “Nels has just come. I guess he’s been to see his girl. I hope that will not put you in the notion.”

Sometimes she can be a bit melancholy. “Time touches us all and it would be nice to have a nice fat lamb instead of the dried old mutton at home,” and at other times she is biting: “If there’s anything good in life, the man gets it and the woman has to worry it out the best way she can and make a slave of herself and feel content. This is how I feel about it. This having a man thousands of miles away, converting fine-looking girls and living on their smiles and flatteries and wondering which one he had better emigrate is not what it is cracked up to be, but you did say in one of your letters that you was not going to do that way. Well, you may or you may not, and I don’t know as I care, but then again, I do care. You say in every letter that you wished you did not think so much about home. I wish you did not. I wish you could forget you had a home. I wish I could draw my mind from you. I fear it nestles too much around you and not enough on the business I have to tend to. How does that sound, old man? Well, that will do of this kind and you can take it for what it’s worth.”

Sanie’s anxieties play out amidst the federal crackdown on plural marriage in the 1880s, and she’s bold and flippant and saucy in her disdain of the practice. Nevertheless, she really is resigned to the fact that one day she is going to have to live the principle. However, Anthon does not take another wife, and I believe it’s because of the economic pressures when he gets home in 1885. He doesn’t have a job anymore, and he doesn’t have any money and they’ve spent so much money while he was on the mission, but he’s in economic straits. By the time he kind of gets that righted, plural marriages are really just way on the wane and it’s becoming very dangerous for men to enter plural marriage. And so he never does, although he’s clearly a believer in the principle.

You sense in these few passages that I’ve read, a bit of the loneliness that kind of infuses the letters. She is desperately lonely without Anthon at home. His absence is felt constantly. She notes, she hears the rain hitting on the window and it makes her think of him. And they call everybody to dinner and the youngest says, “Where’s Papa?” And they think of Anthon. The nighttime elicited these emotions in full force. “It is so lonesome such nights,” Sanie wrote, “to sit and listen to the rain and think of you so many miles away.” She expressed her love in a series of pet names, sprinkled through the letters. “My old man,” “my bummer” “my brown-eyed lad” or “my darling Anthon.” At times the letters pulsate with longing, reminds him of reading her to sleep, talking late into the night.

The letters often conclude with a series of plaintive phrases, sprinkled all over, upside down, backwards. Every way you can imagine all over every page of the letter. So this is from one letter, March 1884: “To my darling in a foreign land. How I miss him and long to see him once again. I hope you will not get too fat. Does your heart beat true to me, my love, now you are gone so far away? Goodbye, dearest, for this time. I would like to send a kiss. I will make up when you come. That is, if you will let me. My love to AH Lund, the translator.”

The pervasive loneliness of a missionary wife was no more acute than when the children were sick. The first night Anthon was gone in 1883, “Henry began to groan and was so sick he puked and had a hot fever,” she reported. Resigned to her lot, she found that focusing on her sick child kind of helped to pass away the time. Nevertheless, she admitted that the nights are very lonesome, no Anthon to call when the children are sick. Danger posed by illness was ever present in the 19th century. Eighty percent of Sanie’s letters talk about illness or death of either their own family or somebody in their close circle of neighbors and friends in Ephraim. It is a constant.

And just as an aside, I’ll tell you when I’ve spoken over the years to groups, invariably somebody comes up and says, “Oh, I bet you’d love to live back then.” And the thought goes through my mind is, “You’ve got to be kidding me!”. But I’ve changed that. I’ve moderated that now. And so what I say is, “well, I’d go back for one day if I had a pocket full of antibiotics,” and that is the reality. So today with modern medicine, we just don’t understand the pervasiveness of serious illness that just hung over everybody all of the time. Her greatest worry was her five boys and childhood illnesses, measles, mumps, smallpox. Diphtheria was the most dreaded of all of them. Those could sweep through a community and take children, just one after another. Lingering under the surface of her worries is this thought, “I just thought, what an awful thing if one of the children should die and you gone.” She couldn’t imagine a greater sorrow or a greater failure. One of Anthon’s own missionaries had to be sent home early because all four of his living children died in a diphtheria epidemic. So that fear hangs over her constantly, and they had already lost a child to whooping cough. They had lost a little girl years earlier.

Sanie also worried about Anthon. She worries about illness. She’s constantly checking, “Are you eating right? And I hope you don’t have a cold or I hope you’re not getting colds,” but she also worried about the potential of violence against Mormon missionaries. So while Anthon is out, two missionaries in Tennessee were shot and killed and three days later she writes him, “I suppose before you get this, you will have heard of the missionaries getting shot in Tennessee.” She then reveals her anxiety, “How hard it looks to have them killed away from home and either never see them again, or have them sent dead. I do hope, Anthon,” she continued, “that you will come home all right, as that, it seems, will be one of the happiest days of my life when we will meet again.”

That meeting presumed that Sanie would also be there to greet him. Sanie had fragile health from childhood; remember she is only 30 years old when he leaves on this particular mission. These letters document the extraction of her upper teeth, rheumatism, pain in the breast and shoulders, liver complaint, indigestion, and erysipelas, which was a serious infection, so she herself is plagued by all of these things. Even more prevalent through these letters is anxiety and what she called the blues, but which we would call depression and I’m no expert on this. I have talked to experts about this and shown them the letters, and they say she suffers from clinical depression and anxiety. She writes, “The blues are cheap,” she notes on their 14th wedding anniversary. “I afford them most of the time.” She worries about her change in appearance. “I have got poor every day since you went, and look as old as Mother. Everybody says how I have changed in the last year. I fear you will not want to own me, for you thought I looked bad enough before you left.” In closing, she wonders, “Do you love me still if I do look old?”

In the end, Sanie states it is not the easiest thing in the world to be a missionary wife. There were many pressures and anxieties just navigating everyday life. She has to take on all these responsibilities which she had never had to shoulder before. I don’t think she recognizes how much she is growing and how much more confident she is becoming in the letters. There was just a constant stream of apprehension that she faced in her life. We have some letters she wrote much later too, and she presents a very different persona when she’s 50 and 60 years old than she does when she’s 30 and in this huge time of stress that she’s facing. At times, Sanie must have really felt that they were crazy.

Piecing together the stories from these letters presents a picture of a witty, long- suffering, strong woman determined to fulfill what she sometimes referred to as her calling as a missionary wife. Her experiences can expand our understanding of a segment of the population that sometimes can get lost between the cracks. Fortunately, Sanie employs her saucy tongue to tell it like it was. She would no doubt conclude this presentation with, “Well, how do you like that?” Thank you.

Q&A

Q 1: Where could I read more about Sanie?

A 1: Well, I hope in another couple years our book will be out. She is, like lots of 19th century Mormon women, somewhat elusive. So she never wrote an autobiography. She did not keep a journal. She demanded constantly that Anthon burned her letters, which was kind of a standard approach for women in the 19th century. Women were expected to disavow their writings; you weren’t expected to be able to write well, and she is just totally embarrassed by her punctuation, spelling and a little bit by her grammar, I think. She had very little schooling. But the reality is when you look at the letters, they’re actually very well written. She can construct a story. She uses dialect, she uses all kinds of frameworks that help you really understand who she is and what she’s trying to talk about.

She tries to paint pictures with words, so she’s actually what I think is a really good writer. But her story is elusive. So without these letters, and I actually think she burned most of the letters from the 1890s because they’re all gone, except for when she wrote a note on the letter somebody else sent her husband. So I think she destroyed those letters because she was embarrassed by them. But trying to find women’s stories can be very difficult because they’re like that. If they didn’t write an autobiography, you have to read through the lines, read through their husband’s journal sometimes or read through letters, and often minutes of Relief Society meetings will often give you a little hint of what these women are doing, and sometimes they show up in the newspaper. So it’s often a hunt to try and uncover the lives of 19th century women.

Q 2: Why do you pronounce Anthon Lund’s name Anton? My grandmother who knew many general authorities pronounce it Anthon.

A 2: Well, my last name is Lund and I’m married to a Lund. That’s how I came across these letters was somebody showed them to me 35 years ago. I knew they were just fabulous letters. [Most of them] were donated to the Church history library about seven years ago. The family pronounces it Anton, which I believe is close to the Scandinavian pronunciation, although Scandinavians telling me it’s more like more often pronounced Antin, but the family pronounces it Anton.

Q 3: I would love to hear Anthon’s responses to her letters. Are they compiled together?

A 3: No, we don’t have the responses to the letters. We don’t know what has happened to those.

Q 4: Did Anthon bring home a plural wife? And did her boys grow into manhood?

A 4: Anthon did not bring home a plural wife. He sent home one of his cousins and she was only 14 years old and I’m sure [she] was not intended for a wife. There is evidence in the letters, because she gets really miffed at him that he wrote to somebody that he had his eye on, someone in the mission. But he did not follow through with that.

Of those boys I showed you, there were five of them there, one of those too died of diptheria in 1890. That’s actually recorded in Anthon’s diary, day by day account as they watch their son slip away. It’s one of the most heart-wrenching things I’ve ever read in my entire life.

Q 5: Somebody is asking about research into his letters back.

A 5: We just don’t know what those letters are, but we do have Anthon’s diaries, which he often mentions what Sanie wrote. Sometimes reading between the lines, you can tell, she’ll say, well, you scolded me in the last letter. And so he could respond sharply when he thinks she’s being way too critical of him.

Q 6: How did I come across Sanie?

A 6: That’s because I married into the family. I recommend that for all historians, is to marry into a family that has lots of interesting characters and lots of documents. I come from a family where there is not one letter from anybody anywhere.

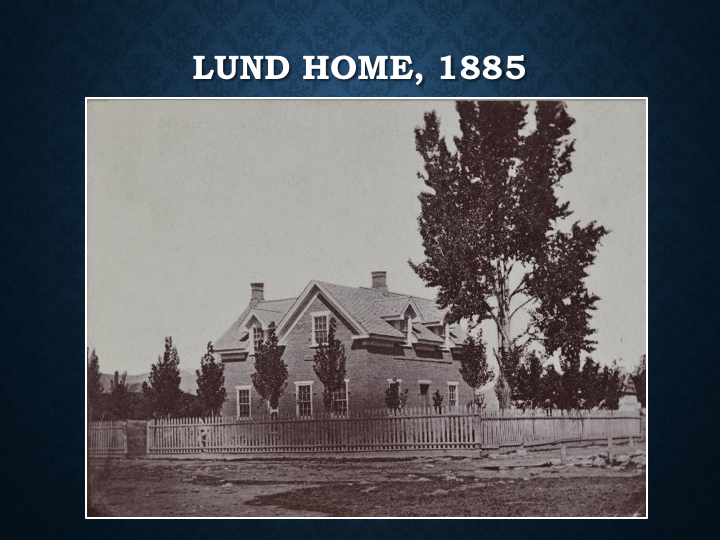

Q 7: Is the Lund home still standing?

A 7: The Lund home in Ephraim is not still standing. The co-op store is standing. It was restored a number of years ago by a small group that got together and raised funds. But the Lund home, if you happen to know Ephraim, [which] would be kitty corner across Main Street, was torn down in the 1960s and a Texaco gas station was built on the location.

Q 8: How did the circumstance of missionary wives impact property law in Utah?

A 8: That’s a really good question. Sanie didn’t try to sell any property during this time period. So I don’t know how that would have impacted. There was a tradition imported from Britain into the American legal system that when a husband was absent, the wife could act in his stead without any kind of special paperwork or anything. It’s called deputy wives. Very common in the 17th and 18th centuries. I don’t know how much that transported into the 19th century.