August 2018

I’m pleased to be here. I was able to speak at another FAIR conference several years ago in a different locality, I guess it was in Murray or near Salt Lake. As indicated here, the title of my talk is “The Presence of pre-Columbian Horses in America.” I had written, about the time that I gave that talk, I’m working on these two books that you see here, Science And the Book of Mormon and Creation of the Earth through Man.

Originally the publisher wanted to have the part that I was going to have the Science and the Book of Mormon as part of the creation book, but he said, “No, let’s make it two different books,” which was done and I guess probably it was a good thing. Now in Science and the Book of Mormon, I talked a little bit about horses and other animals as you can see there on the title and then later on I had been asked to write an article and was helped in this with Matt Roper, who is here, at Book of Mormon Central.

And in this one we get into more of just the animals in the Book of Mormon and discuss them at greater length. It didn’t come out until the early part of this year. Now in this question that was asked, and you can see that this is addressed to FairMormon, and I think it’s a good question, and the answer is reasonable, too: “Why don’t potential pre-Columbian horse remains in the New World receive greater attention from scientists?”

Whoever gave the answer, I think it was reasonable and that is toward the bottom there. It indicates that most scholars continue to believe that horses became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene period. Actually, that should be Pleistocene epic, which is the same as the ice age. They’re synonymous terms. But at any rate in the last several years, I’ve noted that there’s a change. I’ve worked with fossils now for several decades back to the 1960s and I’ve got a lot of friends who are paleontologists, a number of whom have worked on horses and more and more, beginning to realize that, “Yeah, certainly it’s possible that they did survive beyond the ice age or the Pleistocene.” So it’s nice to see a number of them coming around.

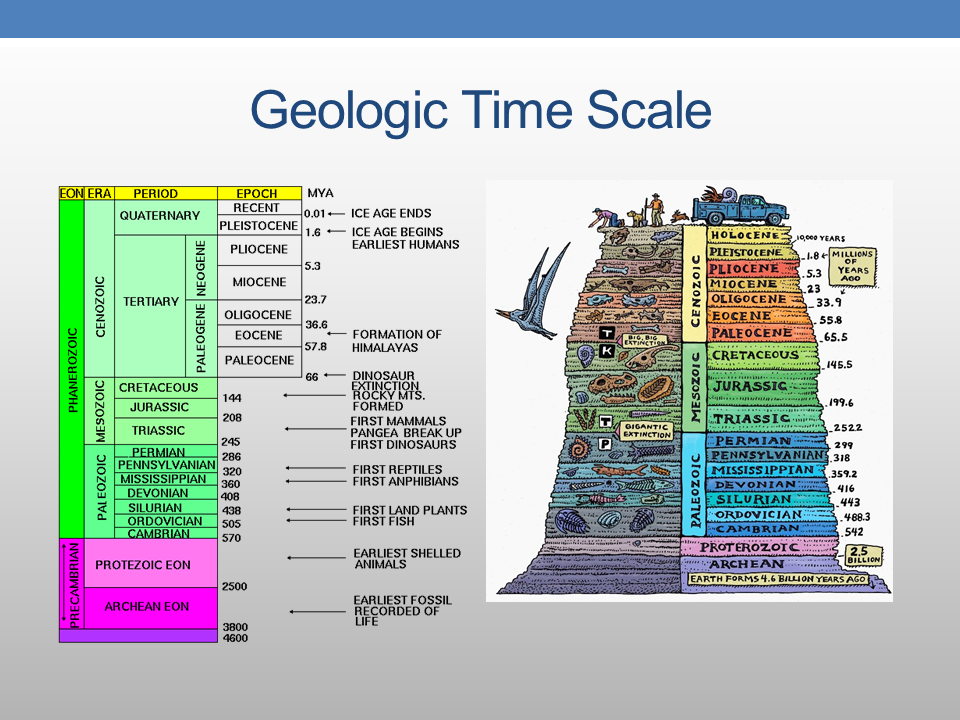

I want to indicate a geologic time-scale here, and the one on the right is a kind of a cartoon, but it does give the various eras in at least some of the periods.

The one on the left is a little bit more accurate in terms of the geology, and even that is not complete besides the eras and the periods and the epics that you see, and you see the Pleistocene is one of those epics. There’s also a set of things called ages, so it’s really a lot more complicated in terms of dividing time geologically going to about the beginning of this fell to the earth formed about four point 6 billion years ago. If you look closely, you’ll see that some of these time divisions are a little bit different on the two scales, and that just shows that we just don’t know for sure.

And so you’ll see slight differences in the amount of time for these different geologic segments of time. Another thing, if you’ll notice it up near the top of epics, it’s in yellow there, that it gives recent. On that one I told you was a little bit more accurate in terms of the scale, but if you look at the one that’s more cartoon like, it says Holocene. Those are synonymous terms, so “recent” is the formal term and Holocene represents about the last 10,000 years of geologic history. Some have maybe the last 11 or 12,000 years even, so there are again, differences of opinion. I want to start out with one scripture here in Ether.

This seems to be the first mention of any kind of animals in the Book of Mormon. Of course, we know that the Jaredite record in the book of Ether goes back much further than does the Nephite record. Things they brought over in the barge when they are preparing those eight barges–they had animals that they were bringing along. None are named here, unfortunately. It indicates flocks. Now, sometimes people refer to flocks of birds, but as Matt Roper says, in the Old Testament, flocks generally did not regard birds. They’re talking about animals. Maybe sheep or goats, so we’ve got some animals, probably pretty big animals that the Jaredites brought over, and I mentioned that in the article that Matt Roper and I did that came out and BYU Studies more in detail than I’ll do here. I’ll be giving you other information here anyway, so they had a lot of decent things they took along with them and obviously food for them.

If we jump about 1,500 years or more into the Nephite record, then we started hearing or seeing where there are some specific animals mentioned, and lo and behold, it’s talking about cattle, the cow and the ox and the goat and the wild goat, but also has underlying the ass and the horses. Now both the ass and the horse are native to North America and in fact some of the same species that are found in the Old World were here. They originated here and from here, and I’ll explain this later. Then they migrated into the Old World, so no problem with this in the Jaredites record and the Nephite record; they were here. It’s a matter of time that we need to get into it, which I will later.

In Enos, two generations later, the grandson of Lehi, here we get some other mention of horses, as well as the goats and wild goats and cattle. So they had these, but they had many other kinds of animals as well. Then going about a few more generations in the Book of Mormon in fact we are going to, at this point in time when this was given, I think we’re a little less than 100 BC. So we’ve jumped in time again.

Still they mentioned having horses there and in this case it was as you remember, Ammon, one of the sons of Mosiah was allowing himself to basically be put in servitude by Lamoni, the king of the Nephites and the Lamanites in this area. And so it talks about not only horses but chariots. So we can infer that probably those horses were used to pull chariots, although it doesn’t say that quite like that.

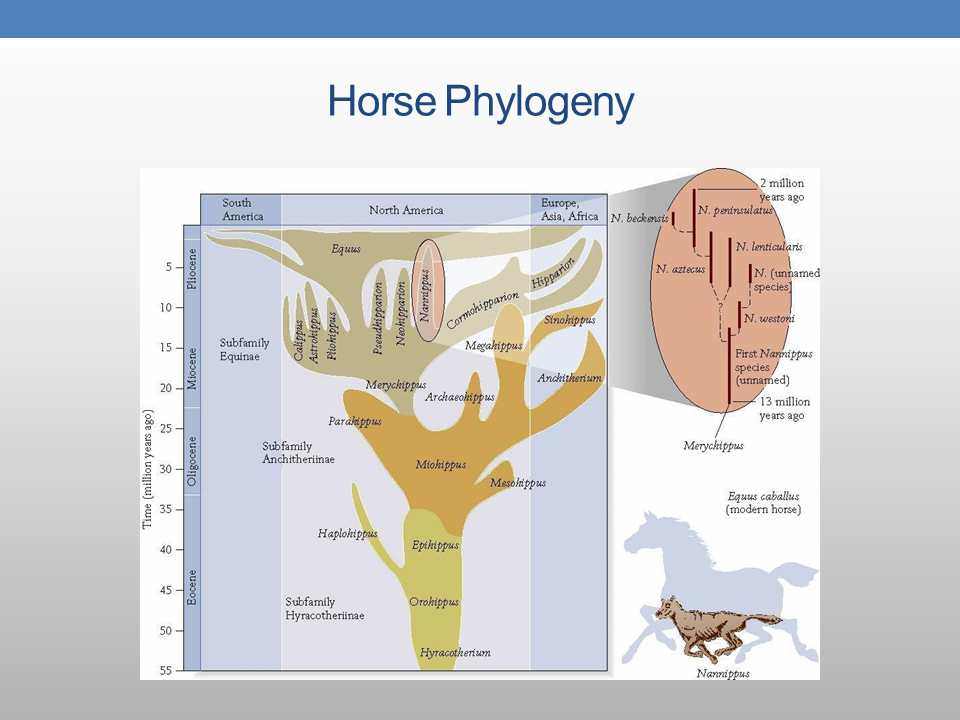

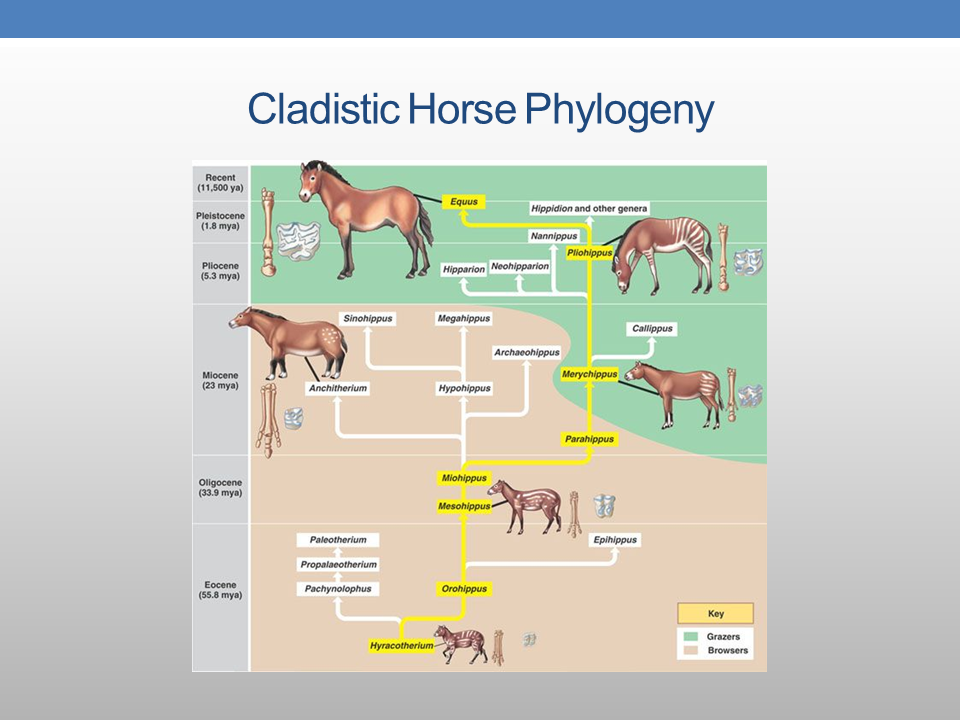

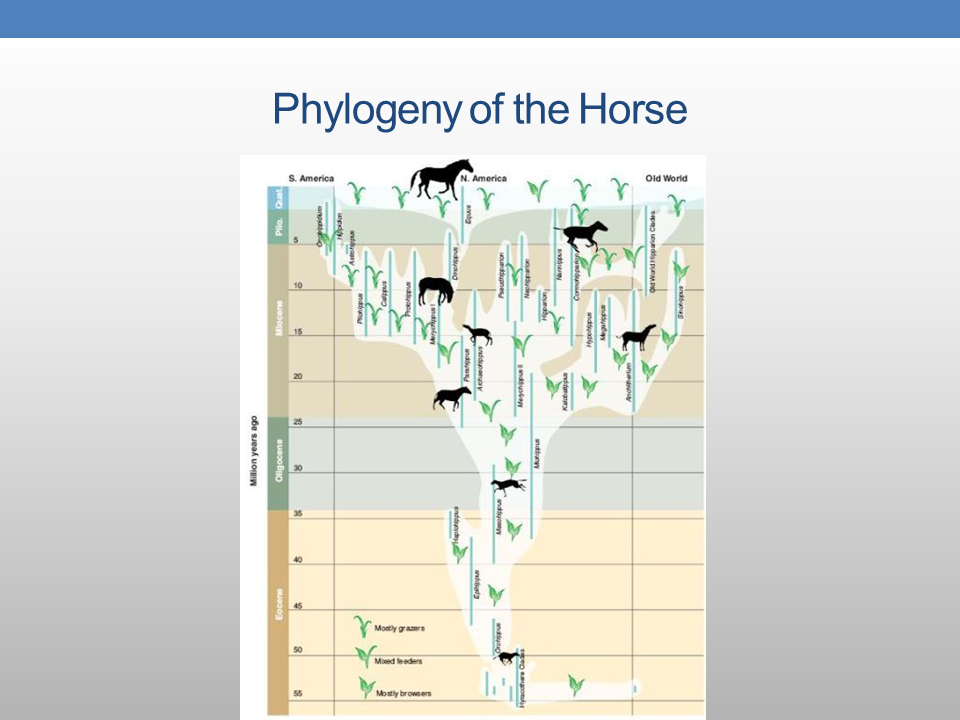

So a phylogeny really is the ancestral-descendant relationships of a group of organisms. It can be plants or animals. In this case, we’re dealing with just one family, the Equids which include the horses and their close relatives. What I want you to look at as you look down the bottom, and I don’t know if you can read it or not from where you are. There’s a first horse shown there, called Hyracotherium. That has been thought for many years to be the ancestral horse, and I’ll get into a little problem here later with that, but then from that horse, which is in North America again, and so this horse, as you can see from this kind of diagram phylogeny, showing a bunch of different genera of horses that developed through time as they changed to meet changing environmental conditions. So we’re dealing with a really tiny little animal to begin with. No more than about a foot tall at the shoulders who was a forest dweller, feeding on leaves and things until we get into later forms that were feeding on grasses and of course had to adapt to do that. If you’ll look toward the top, it has Equus. That is the only living genus of horse now; notice the shaded area where it says Equus, it doesn’t go up to the top in North America. If you look at the top, it says North America, the major history of the horses here in this continent as shown here.

One more point that I want to make on this is the fact that we get back in these early horses during the Eoscene times, we’re dealing with a 45-50 million years ago or so. Along with students at BYU, we collected some of these primitive horses in both the Uinta Basin and also in Wyoming, and then as we go up in time more, my study had been done in some of the later horses. We get into the Miocene and Pliocene than a lot of work over the years there with the horses is different genera that has shown here. Then finally we’re just left with one in North America and in fact one throughout the world. And that’s Equus. And then notice it just stops there. As you get up toward the top, you can’t quite see it, but the Pliocene would be that little square on top and that would go from about 1.8 or 2 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago. So what this diagram is showing is that Equus in North America just stopped being here, became extinct in America according to studies that have been made, about 10,000 years ago–the close of the ice age of the Pleistocene also in South America–became extinct there. But where it continued is that it got into Europe, actually Asia first and Africa, and Asia, where they still exist. The horse binomial system was done by Carl Linnaeus, Carlus Linnaeus, as he called himself, even in the 1700s . And in 1758 he named Equus in this binomial system that he developed, an Equus with a species name caballus. And if you’ve ridden horses anywhere, [it] has been Equus caballus.

Some of you are probably too young to remember who Roy Rogers was, but he was kind of a star of Western movies, and his horse was Trigger, and so that’s Trigger that I’m riding on as a boy. My parents got to know Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, who was a co-star and his movies and some of them were done at big beer and that’s where I’m riding a horse here.

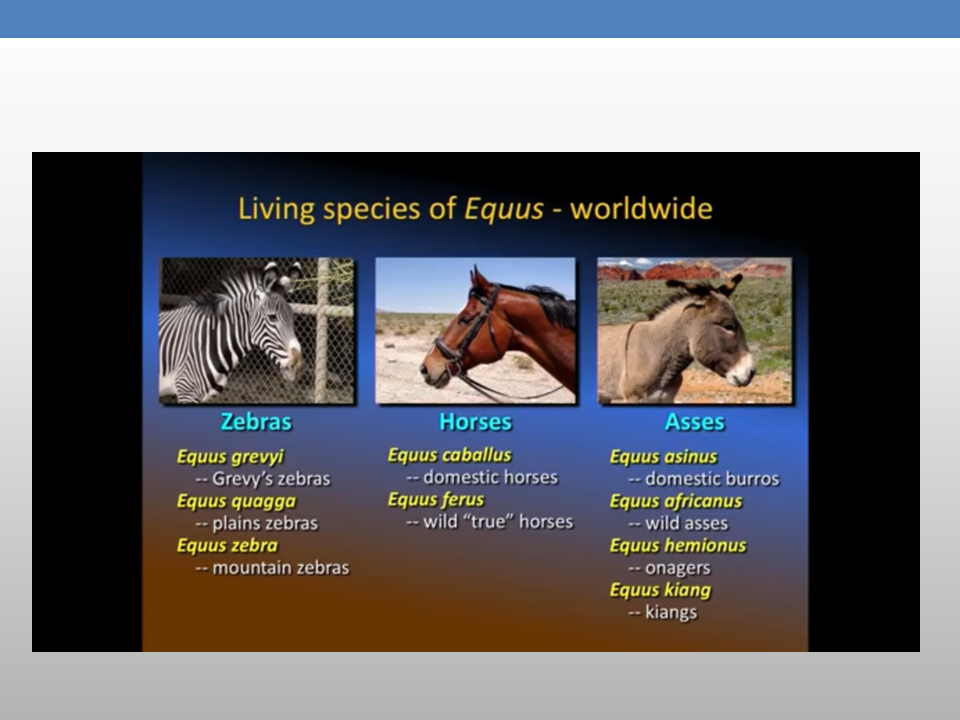

Then if we get into the close relatives of the horse, they too of the genus Equus, the zebras and the donkeys or, as you can see in one corner, Plains zebra shown there. One interesting one is the lower right hand corner. It’s called a quagga. It’s kind of a type of zebra. It was a separate line, separate subspecies, some say species, until the last one died out in 1875. They’ve tried to back breed it by the way, and I think they’ve been reasonably successful reconstructing the quagga.

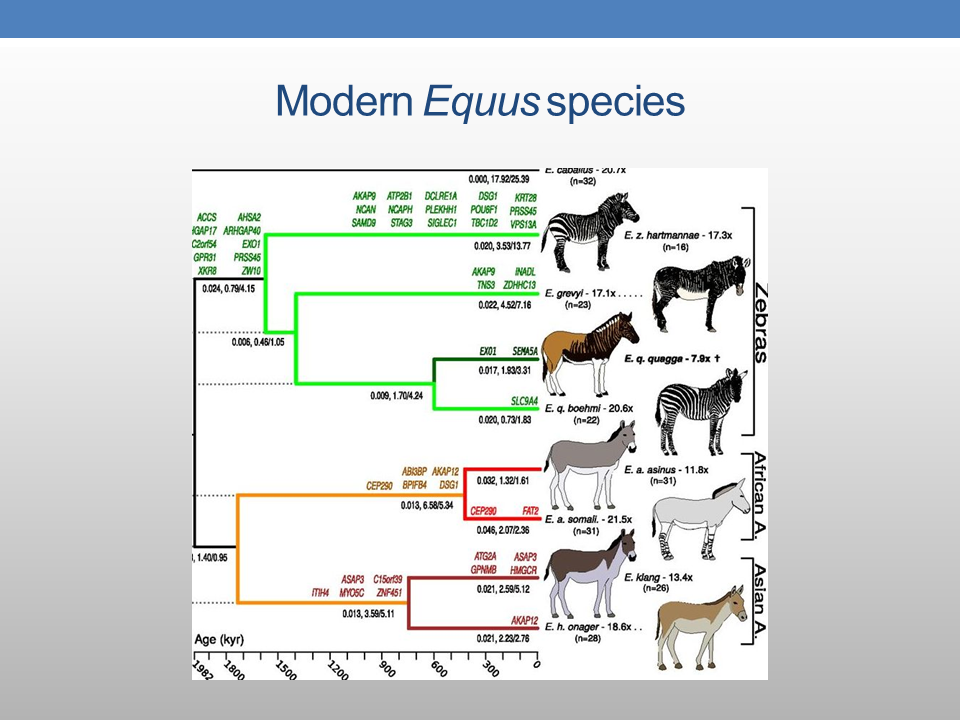

Again, it shows some of the living species of Equus shown here from all the continents, of course, except Australia and Antarctica, and they’d been introduced to Australia. Then modern Equus species.

This is called a cladogram and it just shows shared characteristics of how closely related some of these things are, and if you’ll look in the bottom corner there, like the horse, the asses have been reintroduced to North America and so an ass is shown there in the bottom corner.

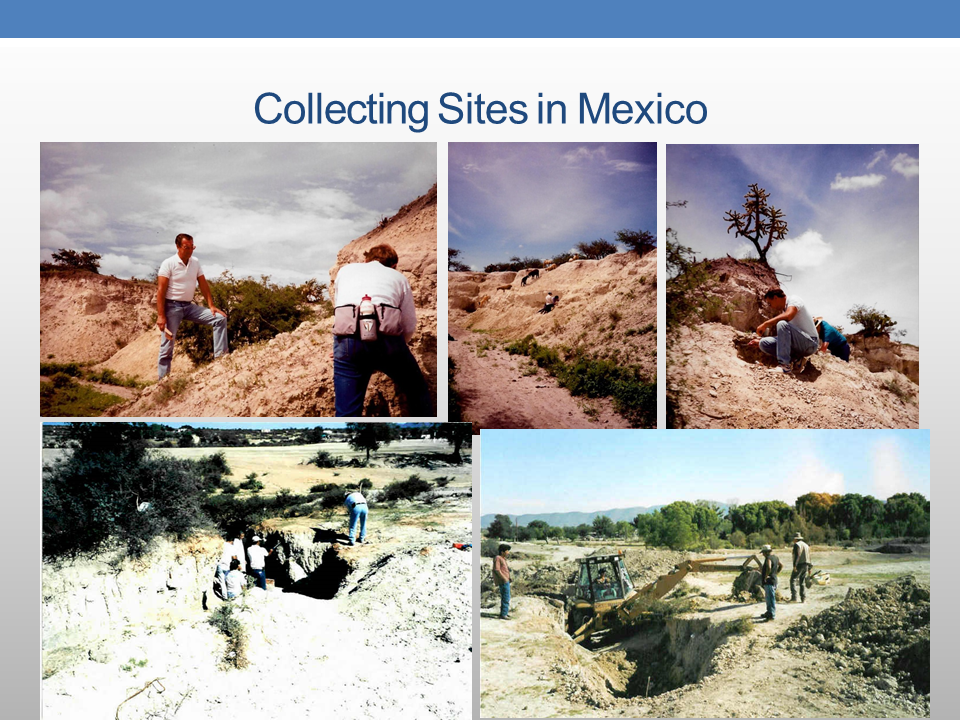

This is one of the areas that I worked out in Mexico, and what’s interesting is that even today, things like the mule would be an Equus, a hybrid between a horse and an ass. So they’ve been used especially in the late 1800s and especially in North America where a lot of the fossil collecting was done in western North America. It was done on horseback and horses or mules pulling wagons.

So this again is in Mexico who have been working in a site near there that showed a lot of horses too, by the way, fossils. This is called a cladogram and that’s why it’s called cladistic horse phylogeny, and this has been a more modern way of showing shared characteristics. Won’t go into any details here, but then the problem makes this if you look down at the bottom and there’s our friend Hyracotherium regarded as the first horse with the founder of the Equid family family Equidae, but there has been some question, and where you see Hyracotherium and yellow and you look off to the left, there’s a group showing three Genera, they’re called Paleotheres, and it’s now thought that Hyracotherium, realized by a lot of researchers, is probably the ancestor to these Paleotheres which are known in the Old World, and then another form is thought to be the ancestor that would continue in yellow going up to the top there, which is the genus Equus, as I indicated Equus caballus being the most common species.

Well, they had to have an ancestor, that is these early horses, as well as the Paleotheres, and they are called condylarths. These are probably strange names for you. In fact, with students we’ve collected in the Uinta Basin some condylarths as well, but these things gave rise not only to the horses through time, but horse relatives. I don’t know how familiar you are with the family Equidae, but close relatives of the horse are the rhinoceros and the tapir, plus extinct forms like Titanotheres, Hyracodons, a bunch of stuff, has become extinct through time, of course, and not only the condylarths are thought to be the ancestral form for the horses and their relatives, but also to the cattle and in fact a group called the Artiodactyls and other groups of animals, the Artiodactyls including the cattle. So these were kind of a founding group that is the Condylarths: different species, different genera, to a lot of the things we have living today.

Again, getting back to Hyracotherium. This is a picture taken in about 1852, Sir Richard Owen. He was one of the founding fathers of paleontology after Couvier, who came a little bit earlier, and he was a brilliant anatomist. In fact, he identified things sent up from Australia and New Zealand, so people who wanted to know what fossils were would commonly send them to Richard Owen who would identify them, and he identified one from New Zealand as a flightless bird, which is amazing considering when he did that, and what material it had to work with. Now, he was a gifted anatomist as indicated here, but he wasn’t especially well liked. He was kind of cantankerous, [according to] some things I’ve read about him. You look at his face and you think, yeah, that’s possible. Anyway, Hyracotherium is a beast that he named. He was given some material actually not that far from London, from some sediments known as the London Clay, and so he recognized it was something new to science and so he named it Hyracotherium.

He named it Hyracotherium because oddly the thing that was closest to it was a thing called the hyrax, which is from Africa and the Middle East. The thing is not very big. Maybe they got up to about 12-15 pounds, something like that, but it’s not all that much smaller. The teeth and the lower left is part of the upper tooth row of hyrax. The one on the right is a sample that was sent to Sir Richard Owen to identify, and so he could see that the teeth are very, very similar. They were hyrax-like and so he called it Hyracotherium and the name has stuck. It was scientifically and formally named. He gave it as a paper, I think in the last one in 1839, but it was formally published in 1841. The teeth if you look more closely, are kind of like the Greek letter Pi and that’s typical of not only the horse but things like the tapir and the rhinoceros indicating their relationship.

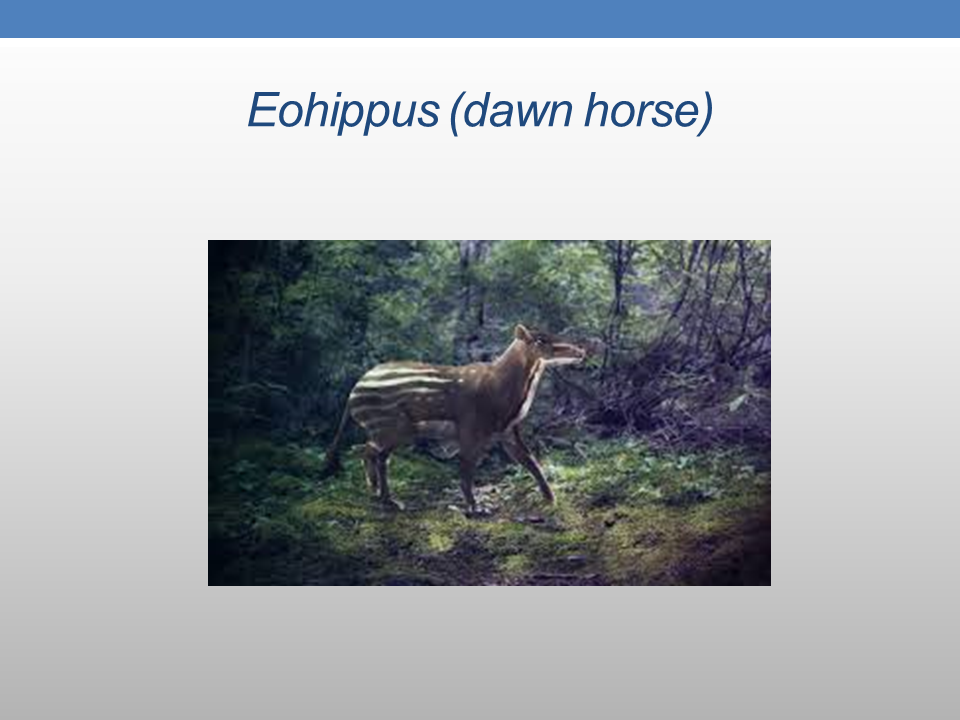

I don’t know how many of you have heard of Copa and Marsha. I’ll go into this because it’s really an interesting story. These guys got in the headlines of newspapers in America for years. They were starting out as friends. This is back in probably the 1870s and then became very bitter rivals and enemies of one another and I could go into a lot of stories. They’re very funny, but there’s no time. Anyway, in the background is showing something else. While the two guys I mentioned, Joseph Lidy, a book was written about him: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. It’s pretty interesting. I mean he was really a great scientist. He studied not only fossil horses but bacteria, and I mean just a wide range of things that he studied, and he did a very good job. He named a lot of different horses, as matter of fact. Well then the ones that came along later after they began their rivalry, he just got out of the business. He says, “I’m going back to bacteria and little organisms like that,” because he didn’t like what was going on. Anyway, so he got Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, that’s showing the portly guy in the corner, but was a great paleontologist, and he was sent material of a very primitive horse and he named it Eohippus.

Maybe I better just say next, a depiction of that Eoscene, very early Aca. Maybe going back even into the latest Paleocene and as Anik, maybe I didn’t indicate. Anyway, I indicate about collecting some of these , with students from BYU, that these things have been found. The earliest ones in Wyoming and surprisingly Baja California, so some of the oldest ones of this Eohippus, which for a long time was considered to be, in fact still is by some, a synonymous with Hyracotherium. So if you can think back that other chart that I showed before and I wanted to go back to it, you can look at this as being the ancestor then of our modern group of horses, starting out in North America.

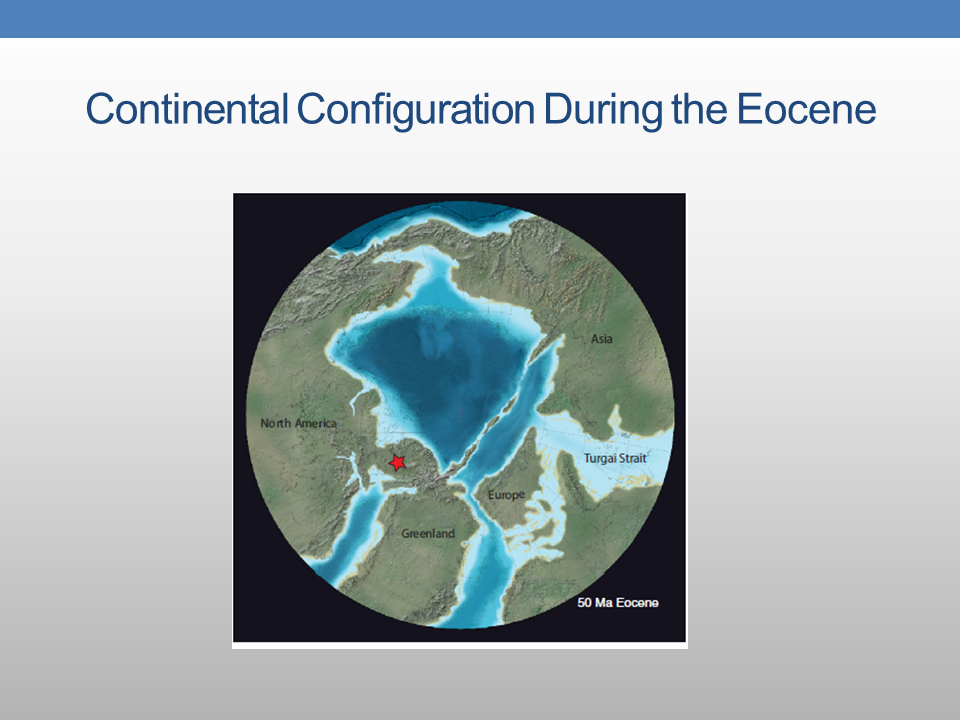

Where horses first appeared on earth (and I might give credit to Eric Scott, the one that did this and a couple of other slides, including the last one. He’s a fellow paleontologist who’s worked a lot with horses and still does.) Horses first appear as indicated there in North America. And from there they spread to the rest of the world. Well, how do they get there if they’re in North America? I mean, that’s a long swim to get over there to Europe and to Britain where Hyracotherium was found. So something was going on in the past. Most of you or at least many of you probably know that the earth is made up of a series of plates and so there’s this part of geology, plate tectonics, so all of the continents and all the ocean basins are resting on a few plates that are making up the surface of the earth and they move independently and this has been well established now for years and so through time these have been moving around and they still are.This can be measured by lasers and satellites and other means to know even how fast they’re moving. They’re moving at different rates. Some of them are moving as fast as your fingernail grows. Not fast, but over millions of years, big distances are involved.

So in the past, if you look at this, it’ll take you a minute I think to focus on it, the star is showing an area where through that area from what’s called North America and Greenland, which is now part of North America, and you get all into Europe. There was a time in which the continents were connected there in the Eoscene. We know this because there are so many similar animals and plants that weren’t similar before, and later on as they changed through time, they weren’t similar after, but during the Eoscene they were very similar and that’s why Hyracotherium and Eohippus have been confused and conceivably still are the same, but as I indicated they, are enough different anyway, so this is indicating how they may get around. This is back on Eoscene and we’re dealing back 57 million years ago and I know geologists throughout, you know, years, billions of years, like they’re nothing. So don’t lend money to a geologist. I mean, a thousand years is nothing, even a million.

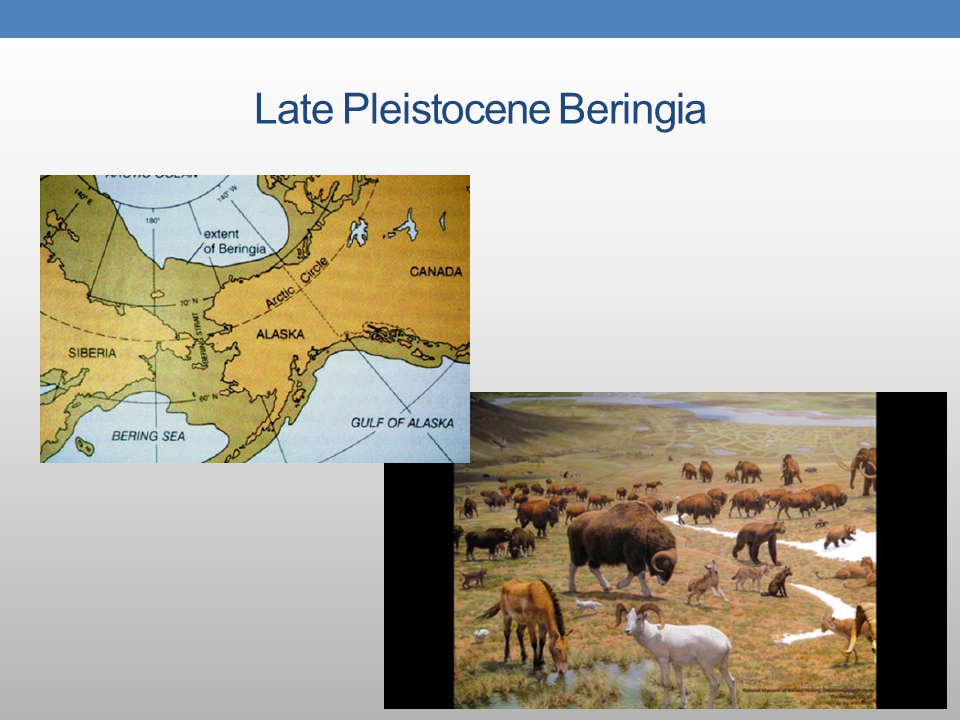

So as we go on in time,now we’re getting up to the Pleistocene. Some things are happening that involves horses, many other animals. If you look there in the upper left hand block, this is showing the continents as they were in the Pleistocene. Well, what happened to the ice? It’s known as the Ice Age. Where did the ice come to form the glaciers? It comes from mainly the oceans’ waters, and so as glaciers were forming on land, sea level was lowering and at the time of this depiction showing here, it was lowered about 500 feet, so that’s much different. This allowed for a lot of different connections that don’t exist now and it’s called Beringia. You probably have heard of the Bering Strait and in fact the name is there if you can read it, called Bering Strait, that narrow strip of water that separates Alaska from Siberia now, but back then the continental shelf was connecting. In fact, it was a broader connection as you can see between Alaska and Siberia than these countries are now So at this point in time there was a lot of dispersal. You may say, well why? If you had glaciation because these animals go back and forth. There were ice free corridors depending on the time, so animals that could live in this area, that is they had a type of habitat that they could adjust to in Siberia and Alaska, easily went back and forth and that’s what the other depiction of these animals being restored with a horse being there in the foreground, so this is when the modern horse got into first Siberia and then from there into Europe and Africa. At that same time the bison came over, which is not a native of North America, and it came across this Beringia, this land connection into North America as did the mammoths, which are elephants, and I’ll point that out later. If you look carefully, you can see the bison and the mammoth, bear and some other things that were dispersing back and forth. Then when the glaciers melted, sea level rose, we have the Bering Strait and you’ve got a separation now.

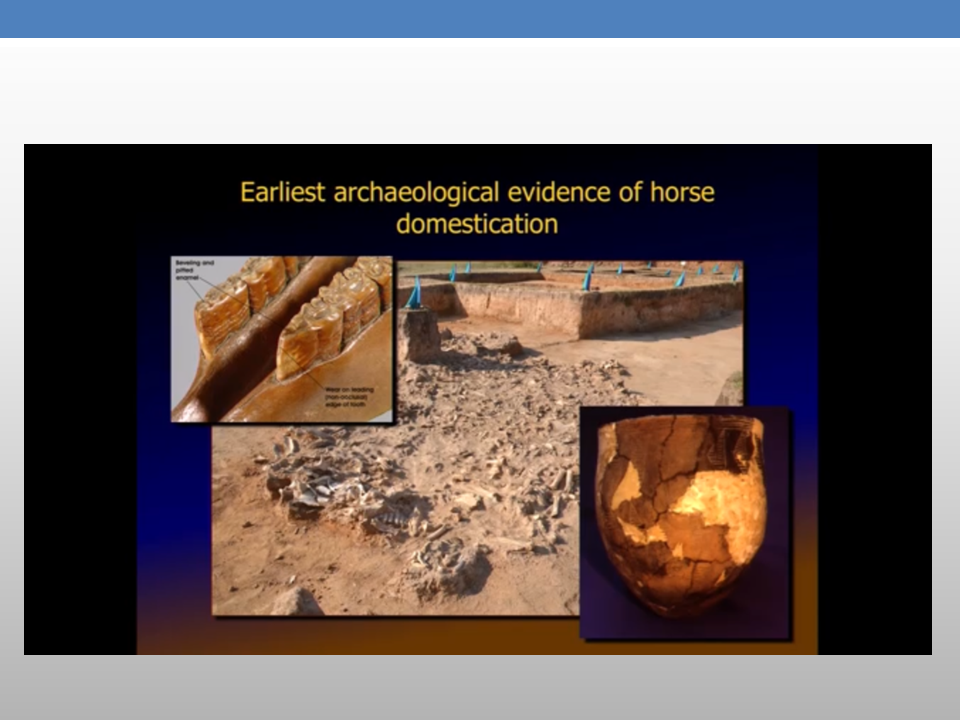

Then when horses then got into the Old World, they were in a time–in fact, I was greatly surprised to see this. As you can read it, the archeological evidence indicates 3,500 BC. That’s a long time ago that horses were thought to have been domesticated, but they’re useful animals. Probably they were used for food and then later somebody got the bright idea, hey, we could use these to do some work and I won’t have to do as much. Botai is thought to be one of the first places, but then almost simultaneously they’ve got evidence for domestication of horses all over as you can see the stars and even more places than this.

Some of the evidence, if you look at the middle part, there’s just a whole collection of bones and teeth of horses there. Probably some other stuff mixed in. There’s actually evidences for a bit in this horse’s mouth and so the wear patterns are very typical of a bit, and they’ve got that for more than just this one specimen that helps indicate domestication. They’re actually riding them. And then the lower right hand one. I don’t know if you can make that out, but it’s kind of a pot, partially reassembled. DNA studies show that that held mare’s milk, the milk of a female horse, and so all of this is led to the belief of a very early domestication of the horse. Certainly in the Old World.

And here is a Mongoli; the Mongols were known as great horseman, he’s got a bridle there if you look closely, but he didn’t have a saddle.

Then we get on more toward modern times (and you can’t read this–it should’ve been different colored title.)

Yes, but at any rate, they were reintroduced and Columbus a second voice in 1493 was when horses came back for the first time. Then shortly after that, Spaniards kept bringing them over, mainly on the eastern side because he had to go all the way around the Cape in South Africa, Cape Horn to be able to get up to the west coast. So it was a long time really, you need to keep this in mind, before horses actually got to the West from where they first were introduced to the East in the Americas.

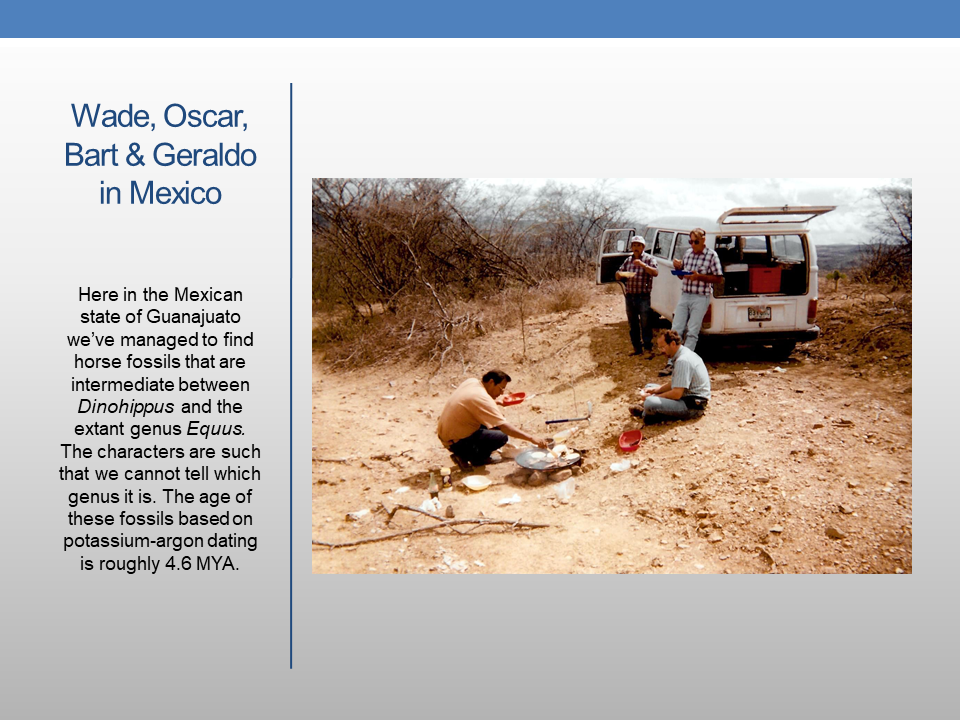

So another chart, again showing a more conventional type of phylogeny of the horse. It shows the earlier ones down there actually showing Hyracotherium in there, probably can’t read it, but what’s depicted in this one is that the early horses were mainly browsers feeding on leaves, but in the Miocene grasslands became established in the world, and temperate areas and horses have lived in that area, began modifying to be able to feed on the ground, feed on the grasses.And so they developed a different tooth. The horse is interesting in that it shows a complete transition all the way from these early browsing forms into the grazing forms to Equus caballus that we have today. If you look at the top where it shows the modern horse here Equus, and if you follow that line, there’s one of you jumped to the left and it’s called Dinohippus. If you follow that out, you see the two of them overlap a little bit that they seem to have coexisted for a little bit. And this is it around four and a half to 5 million years ago. Well, I’ve done a lot of study in Mexico, in this area with this horse called Dinohippus. We’ve got one that we can’t tell if it’s Dinohippus or Equus and so felt not only by us, but other researchers that this was the ancestor, the genus ancestor of Equus, and it seems like this happened in Mexico. That is in North America. At least that’s where we have the first evidence.

My friend and colleague has been for a number of years, Oscar Carranza, who’s standing the furthest [out] with the open door. I’m leaning against the van there eating lunch. We were all eating lunch and then Oscar’s a helper there, leaning over the fires and then the one sitting there, is Dr. Barker Wallace, who’s at BYU, and we worked a lot together down there. Now he’s not a paleontologist, but what he has done as a geologist is specialized somewhat in radioactive dating, radiometric dating and so through fission track dating and potassium argon dating. He’s helped and sending off to the labs that we’ve gotten dating of this horse.

Like I said, this is intermediate between Dinohippus and the modern horse Equus, and this is Equus occidentalis, the western horse. In fact, occidentalis means Western. This is the one that’s a primary one at Rancho La Brea that I want to get to, so that’s just a depiction of what this wild horse was like before we get to Equus caballus.

And I need to give credit [for] at least that diagram and the upper left of that map to my friend Eric Scott. Now, if you look and you probably can’t read it, but all those yellow markings are areas in which Pleistocene horses have been found. That’s in western North America, actually, southern California.

If you look at the very bottom, it’s not quite centered, but the bottom one that’s yellow is called Costeau Pit, the same number that you see on top. Well, that was a new fossil site back when and I was the one that helped develop that [and] had a little bit help with students, in fact natives and the little kids would come around and want to help and so they did. Anyway, so all these down at the bottom and I can’t point out is on there, but it doesn’t show. That map at the bottom is actually from my book, which came from my doctoral dissertation shown on the right and most of those sites show horses and in fact Costeau Pit where I did much in my dissertation work, my research for it, I identified 24 different horses there. I mean same Equus probably equinox, intellus species, but 24 individuals. So there’s a lot of horses there. A lot of horses in southern California.

Then getting back to Mexico who have been doing collecting recently. A lot of different kinds of animals. The most abundant one that we found at various has been the horse. We found seven mammoth tusks there in that trench.

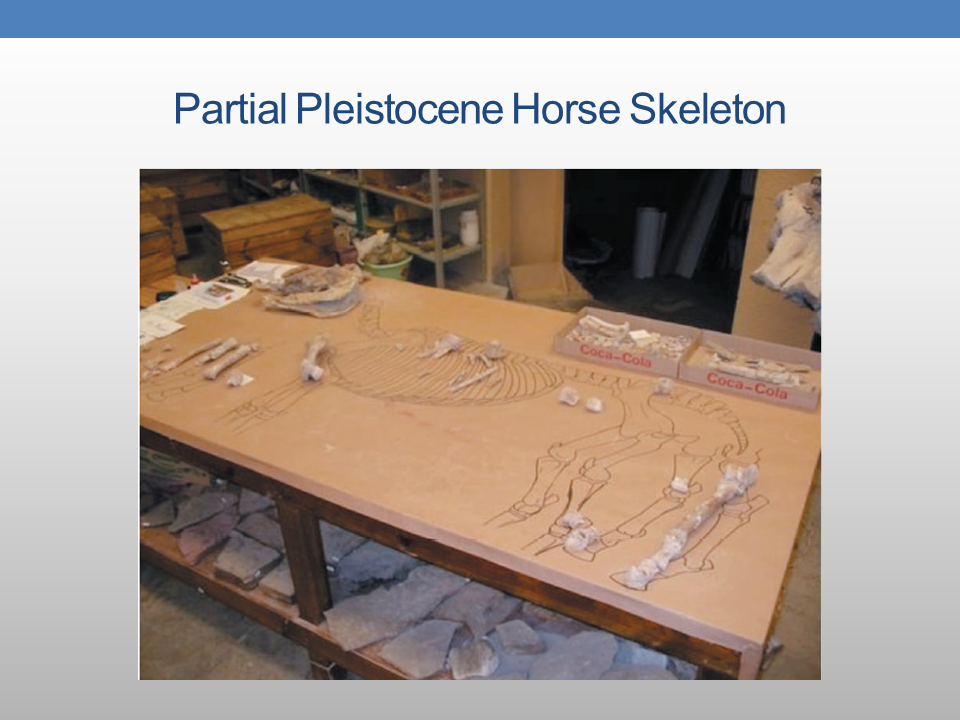

Then another place in Mexico that we worked a few years ago was in the State of Durango. What you see there is a horse jaw, but if you look closely, there are other bones here. In fact it’s like jack straws or interdigitation of a lot of different fossil bones. They collected in a stream at a point bar in a stream where the stream slowed down; bones and things were carried down to settled out there. Then got covered as a stream deposit and more sand. Well time went by and the stream changed its course and then came back to this area and exposed it and we just actually took and made plaster jackets. We trench around and if you know what I mean by a plaster jacket, but you’re familiar with that with you know if you had a broken arm or broken leg or something, so we use the same kind of plaster, but we’d dig a trench all around a bunch of these bones and then put burlap down, soaked in plaster and then as it dried, then we would dig it up and then bring it back to the museum.

This from that site that you just saw, in fact, up in the upper left on the table there is one of the jaws of that same horse and the skull, a number of other bones. Those bones are all from the one horse that you saw on the last slide. Same individual.

Other work in Mexico at the lower left shows the atlas or the first cervical or neck vertebrae of a horse, and again, we found a lot of different kinds of animals there in these badlands here in Mexico, but mostly it’s been horse. Second will be mammoth or elephant.

Just briefly, these are just some of the names that have been given. Most of these are actually places Plioscene, some Pleistocene and that isn’t even all of them. There have been over 50 names, species, of Pleistocene horse and I thought when I was working on my dissertation now that that can’t be right and it’s true. In fact you have to look carefully on there, but you’ll see several different names under one date. Those are just synonyms, horses that are thought to be just the same species. Then I thought, well it probably in reality isn’t more than about seven or eight valid species. The Pleistocene horse now with DNA studies that’s been knocked down to maybe no more than three or four different species of horse. So working with that now.

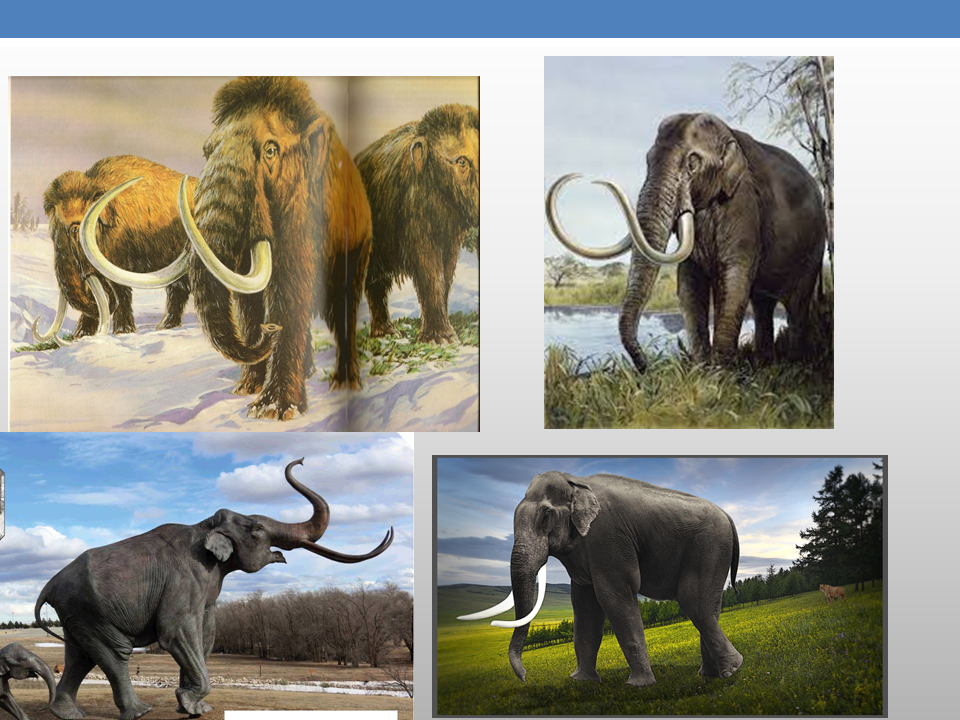

Both the horse and the mammoth. You’ll recall from the book of the Jaredite record that it talks about elephants, and elephants and mammoths are the same and in fact early paleontologist always called what’s now called the mammoth an elephant, and even today a lot of them are called elephants. In fact, there’s a closer relationship to the mammoth here in America and the Indian or Asian elephant than there is between the Asian and the African elephant. Yet we call them both elephants.

Craig Downer is an interesting guy. I don’t really know him personally. I’m pretty sure he’s not LDS. He’s a wildlife biologist who’s made a life study of horses and their close relative the tapir and South America, but mostly horses and. Well, he’s done mainly the modern horse he’s got into the history a little bit too. So, he’s had degrees from accredited universities, including the University of California. And so I think the guy knows what he’s talking about.

Now this comes. I don’t know if you know Daniel Johnson, I don’t know, maybe he’s even here, but he wrote an article in BYU studies as well, and that’s taken from that. So I’ve looked at it and I agree with him. There may have been small pockets of horses that continued to survive here in North America and even South America.

Some other evidences that the horse may have lingered on in North America beyond the Pleistocene or 10,000 years, however it is set up. Not only the Dakota, Lakota peoples, but other Indian peoples or native Americans also have a similar history and then in the verbal or oral history, of their groups that the horses were there even before they were reintroduced.

And then a recovery of mammoth, elephant and horse DNA suggests that they lived on longer, so now getting into more of the scientific work on this, more and more paleontologists are agreeing and yeah, this 10,000 year limit at the end of the ice age for some of these animals like the horse and the mammoth in North America may not be valid. They may truly have continued on longer.

There’s diagrams from the same article that I showed in the last slide. If you look carefully, it shows an outline of a mammoth, which is an elephant and the horse there at about 7,500 years. Well, that’s appreciably past the 10,000 year mark.

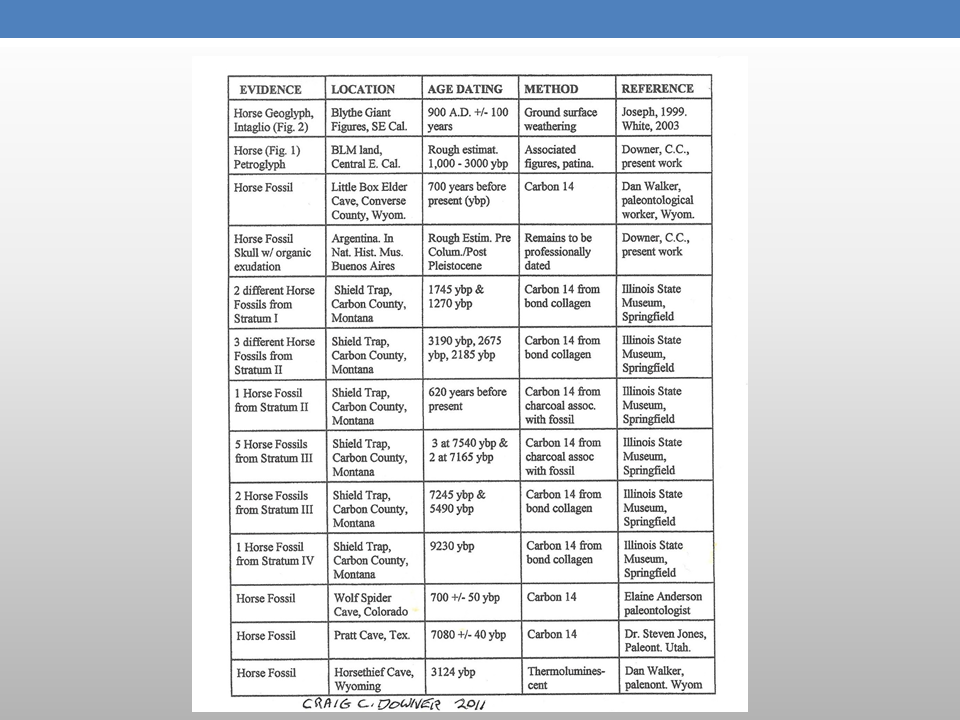

Then this is done by Downer. In fact, these are a bunch of dates here. I don’t have time for you to look at all of them, but some of them are even down to 600 years before the present for evidence for horses. Some of this was actually compiled, I think by Steven Jones who was at BYU that Craig Downer had corresponded with.

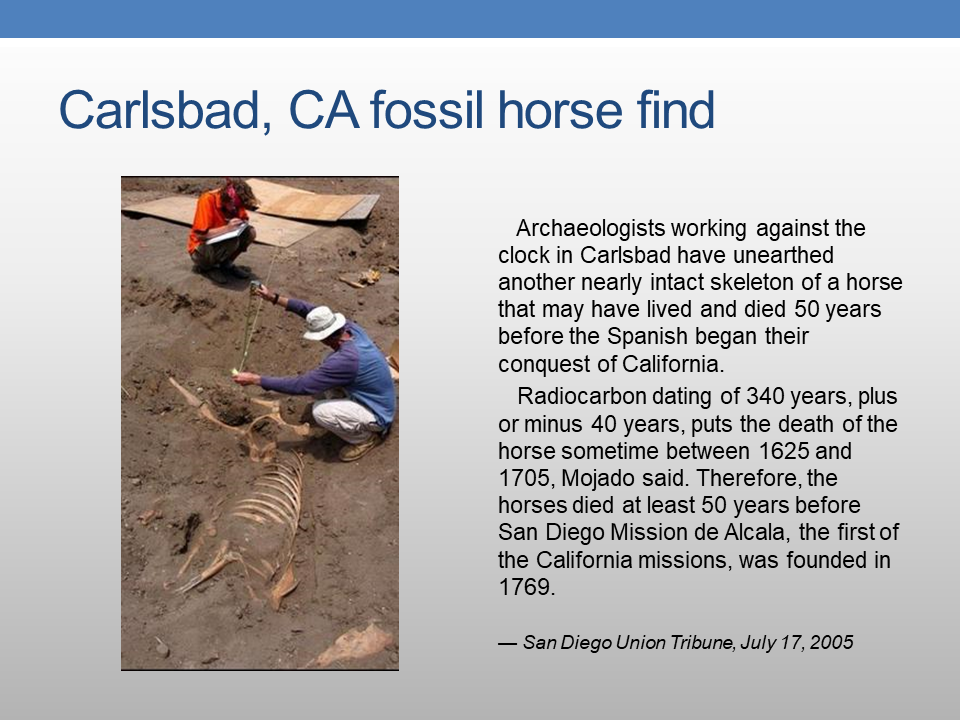

And then another one that’s kind of surprising, Carlsbad, California is indicated here. They found that skeleton of a horse, also most of the skeleton of an ass. The two of them close together there in Carlsbad. And according to the researchers there Mojado, an archeologist, he feels that these animals existed here near Carlsbad, a number of years, 50 years here before they actually got into western North America. The ones reintroduced by the Spanish. So telling you about animals living on past the time they were thought to be extinct.

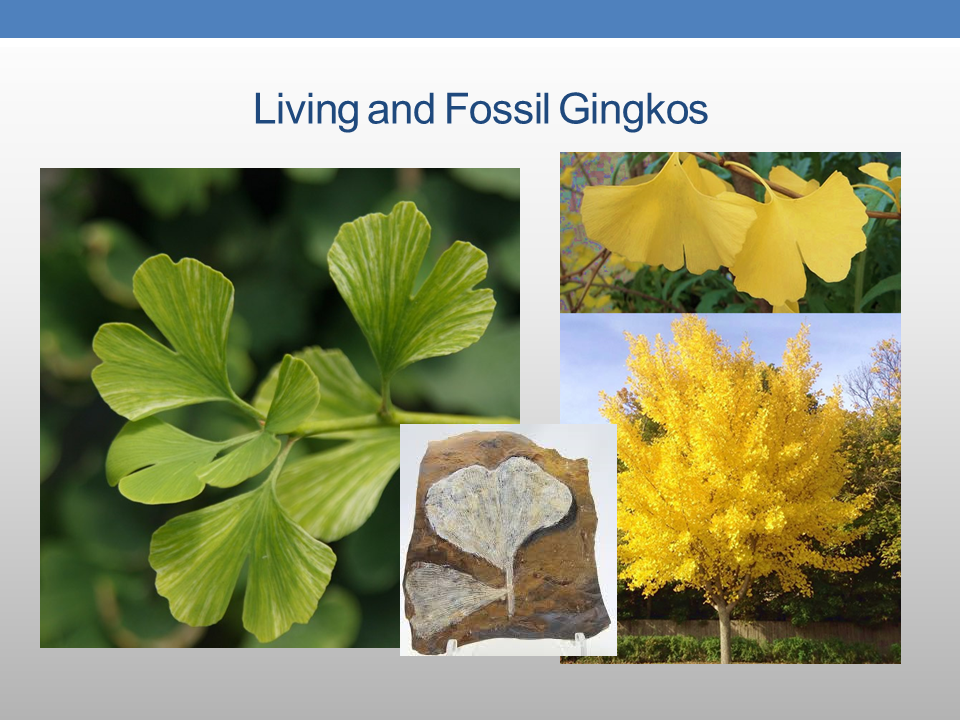

The ginkgo tree here, in fact there’s some other BYU campus and around Provo the leaves that they get going is a deciduous tree that turns color in fall as indicated here, but it shows in the bottom central fossil leaf, a Ginkgo, the Ginkgo tree was thought to be extinct many millions of years ago until they found them is still living in remote areas of China and since then they’ve been reintroduced to America and other places.

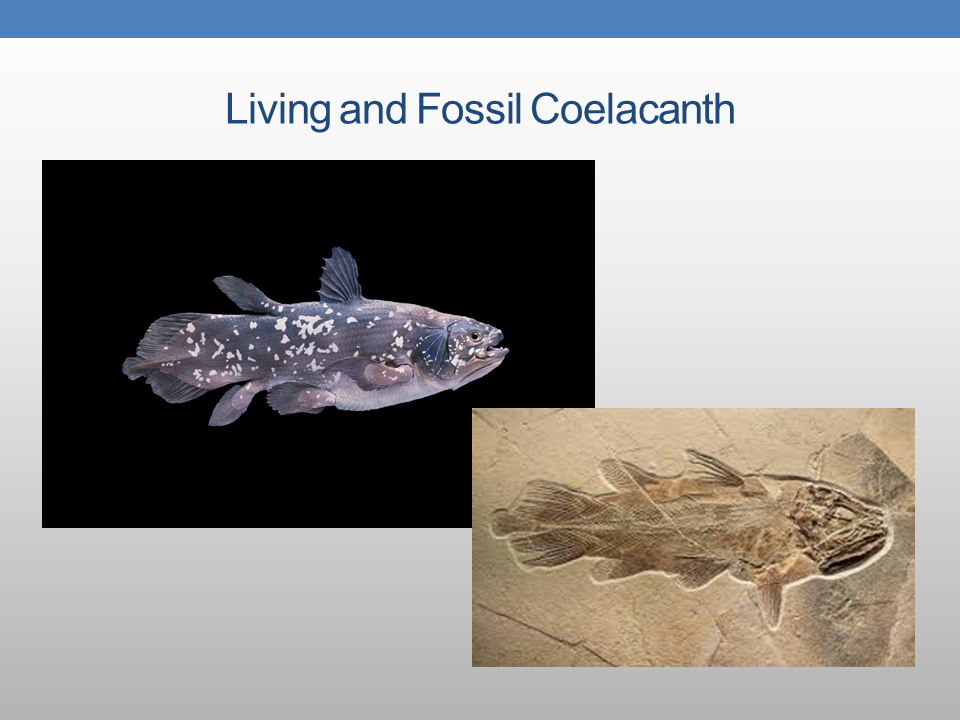

Even more startling, and you may have heard of this, is a coelacanth, the coelacanth fish, that is thought to be a type of lung fish really that’s thought to have been extinct over 65 million years. So think about that. 65 million years. They thought that didn’t exist anymore. Then in 1938, they’d raised one up off the Comoro islands by Madagascar. Found out they’re still living since then, they’ve gone down and taken video. I’ve seen video of these things swimming around. A professor at UCLA, as I recall, it was in Indonesia, and he saw one in a fish market there and lo and behold, they exist in the seas of Indonesia as well. Now this isn’t a little guppy size fish here. This thing could weigh up to 200 pounds, so we’re telling you about, you know, a substantial size and you can see by comparing that is very close to the fossil forms, so they didn’t change much in 65 million years plus.

The Okapi, which is known as a fossil before, was known that was still living, found in the 1800s in the Congo area. Now they don’t have to still be living in an area, but a lot of times the range of fossil animals, went on for hundreds, thousands, even millions of years as shown here and found out they lived on far longer. Maybe became extinct later. In fact most things did. The last few minutes that I have here on a point this out that you probably can’t read it, I’m going to get above the mic.

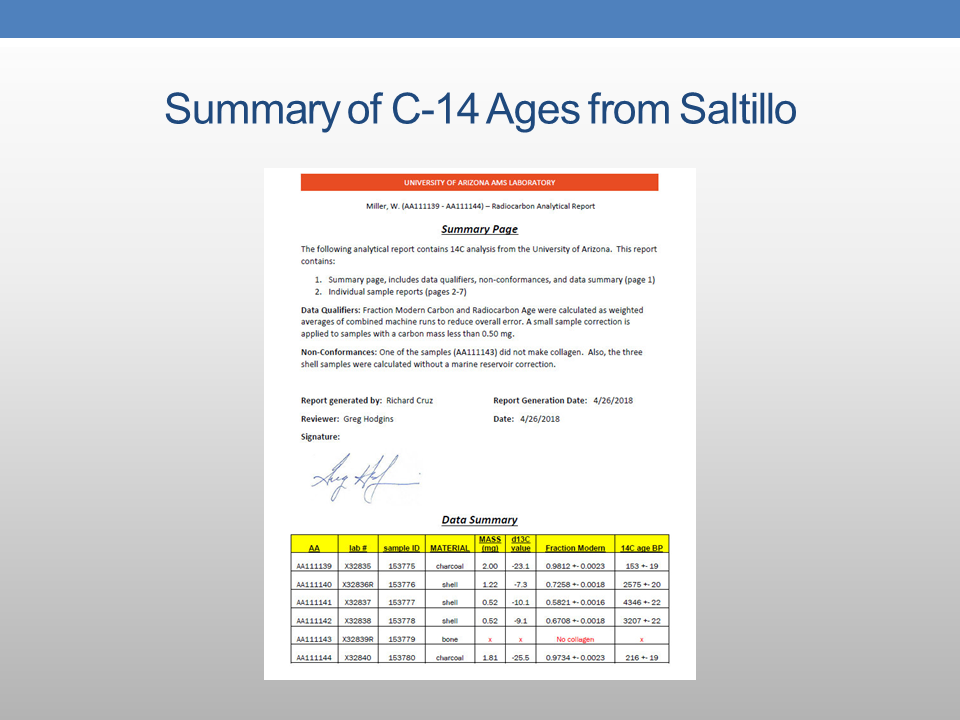

The bottom form is one of the areas that we collected in Mexico, we had a lot of mammoth, had a date sent out to the University of Arizona, AMS carbon 14 lab, and they gave a date there, 49, actually greater than 49,000, years in other words they couldn’t date in need older than that, that that individuals we had there were just simply older, but the thing that surprised even shocked me is the top date of a horse based on a horse. Somebody had turned off and if you can read the date is 2,540 years. That’s in book of Mormon time and I was just totally shocked. Anyhow, as I thought about what we need to go down and do some more substantiating of this and Kurt Magelby of Book of Mormon Central along with Matt Roper [I think they’re both here.] thought, “Well, let’s go down there and look at it” and they helped subsidize another trip for me to take down there.

There’s Kurt standing to the left and Matt and also Daniel Smith who works for Book of Mormon Central and you have the people that I’m working with down below and this is where we found a horse skull that dated, they gave us, 2,540 years and we found a number of other horse bones and as serendipity would have it when Kurt and Matt and Daniel were there, we found another horse skull in the same area where we were digging now, that we excavated when they were there, plus other teeth and some bones of some other animals as well.

So [we] sent that material off to get dated. And again, I just don’t know if you can read it from where you sit but I’ll have to point it out. And this is where problems started arising. The top and the bottom dates are one was I think 183 and 216 or something like that. That was based on carbon 14 dates in that area that was run at the same time it had running done of the dating for the horses. And so there’s such a wide disparity, something’s gotta be wrong. At first I thought, the carbon dates, the carbon fragment dates are probably accurate. The ones based on other material, probably not, but the more I checked into it, the more I’m not sure. So there are more dates that I’m having run now to be substantiated and decided to go to another university, University of Georgia in this case, to have one of those samples run there rather than having more run of the same place. So this is kind of up in the air now, but there’s certainly the possibility shown here. But as you can see before, a lot of indication that horses probably did live on much longer.

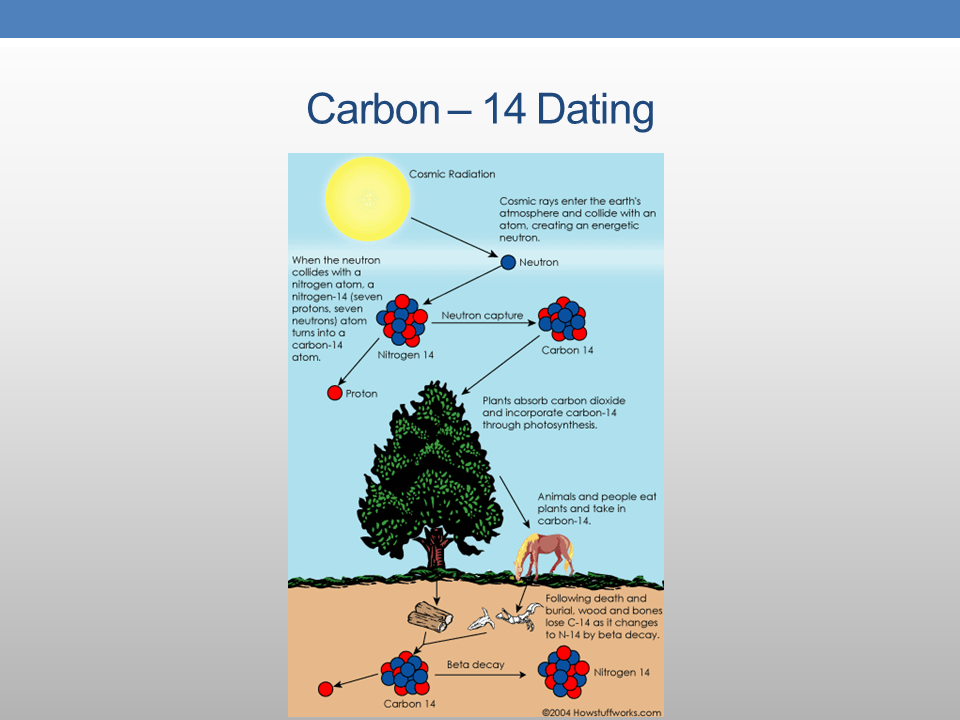

Don’t have time to go into this….The carbon 14 dating has to do with carbon 14 that forms in our atmosphere. It combines with oxygen from CO2 taken in by plants. Animals eat plants. They take in carbon 14 along with stable isotopes of carbon which can be dated by comparing them.

So I just want to briefly mention about the elephants again. Mentioned here in the Book of Ether is showing there mammoths and elephants are the same kind of animal. Go and see them in the neophyte record, but apparently they did actually be going to exchange between the time of the Jaredites and the Nephites.

This is showing the woolly mammoth, the mammoth and woolly mammoth, but actually the one mainly here and the ones we’re finding in Mexico or the Columbia mammoth, which the other ones are the three.

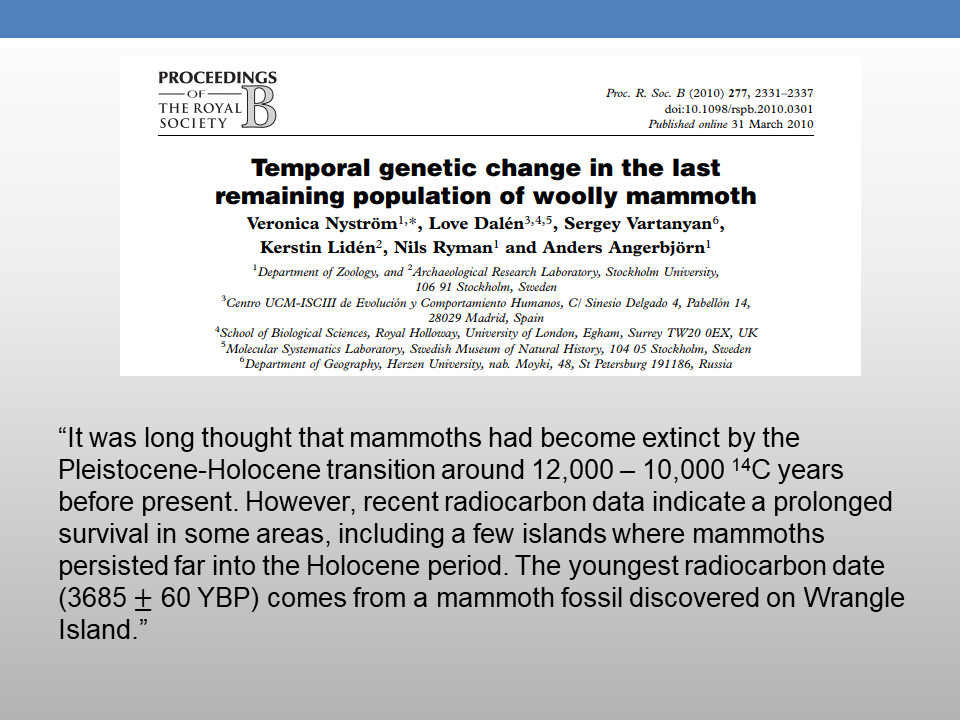

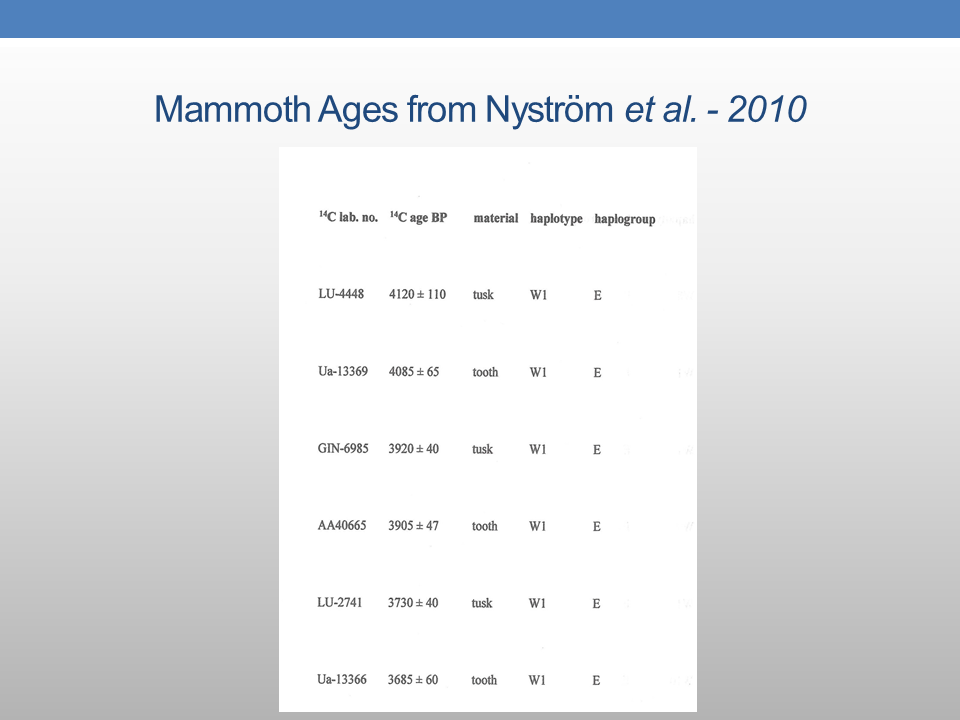

Again, we get into the dating of some of this stuff there. Found out that they lasted a lot longer, a lot of DNA as well as other kinds of studies in carbon 14. I’ll hurry through this show that these things that were living the in carbon-14 date of 35-3,685 years. That’s about 1600 and some years. BC, again, during Jaredites, and scientists pretty much accept this, so they did exist. Now all this is around Alaska, in this area up there. The same thing could be happening. Isolated populations probably lived down further south.

This is just showing some ages here again, showing the mammoth elephant living far past 10,000 years.

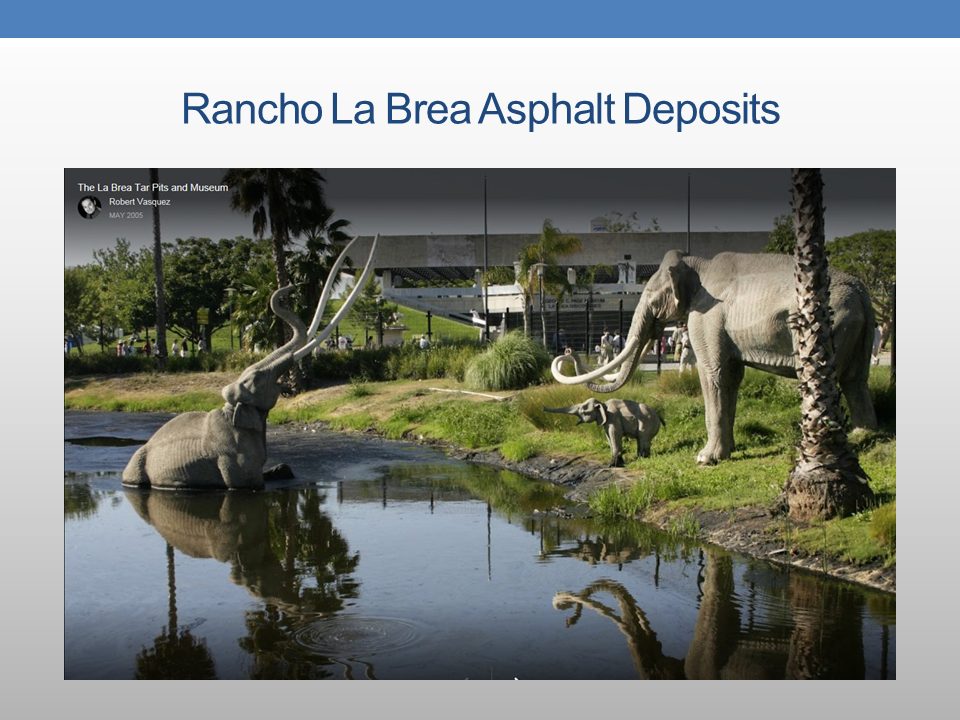

I helped reopen the Rancho La Brea asphalt pits and 1969. And again, one of the more common fossils here, even though it was a mammoth here or the horses. And I worked with a lot of the horses Rancho La Brea.

The work that I’m doing now is being done mainly in Coahuila and the city of cell too, unless they’re a major museum was just a huge muse is really a great modern museum that I’ve been working with. These are the people is the core people that have been working with.

And The lady there in the middle is a Rosario Gomez. She’s hit a paleontology for the state of Khalila. So all of us work together. We’ll be going down there again is September to do some more work now. And closing. One of the things I often ask, I know some of these asset and one of the questions is how do you know where to look for fossils? Well, the next slide should explain that.

Basically it’s in areas like that though, whether or not the rainbow is shining on it.

Thank you.

I’m just going to go out the door there. I will be at a table. I don’t have time to answer it here. I would like to thank Laina Rogers is in the audience. She helped put this PowerPoint presentation together with me, so thank you, Laina.

Thank you.

Q&A

Q 1: In the rockies, the Lewis and Clark expedition came across a tribe of Indians that were expert riders of horses and had very large herds. Has anyone looked if this may have been a pocket or Pre-Columbian horses? What is going on now?

A 1: I think with DNA studies, if they did exist here, like some of these Indian groups believe again if they are in the same species and they could interbreed,I think some DNA studies are being done now to see if something can be done here to determine that. I don’t know to give you an exact answer though.

Q 2: What is your opinion of where the Book of Mormon took place?

A 2: My opinion is, and I put it [like that] in that sentence in the Book of Mormon, that I do think it’s in Mesoamerica. There’s so much evidence. I know there’s arguments for other places and I’d be glad to go into why [I] think [that], which other people have done, excellent people here, so I would say my opinion is along with a lot of others, probably Mesoamerica. That’s too big.

Q 3: What are modern names for cureloms and cumoms?

A 3: Well, I mentioned that in my book because I definitely think that one of the other, the curalom or cumon is probably a type of mastodon or mammoth, probably a mastodon because that’s different than the mammoth, because they did indicate elephants. A cumon, probably in my opinion, where they could be either one, is one of the lamas, which here we call camels, but some of those got to be about seven feet tall at the shoulder. Certainly capable, beasts of burden like their smaller relatives, the llamas and Alpacas and probably could easily be trained, too, if that’s the case.

Q 4: Do you think the sad-faced horse of Mexico and Central America has always been there and this is the remnant of ancient horses?

A 4: You’ll have to ask me when I get at the table because I’m not quite sure on that.

Q 5: What reason do mainstream geologists give for a so called rapid extinction of horse in America?

A 5: That is a good question. I didn’t have time to get into it, but there’s such a thing as C3 and C4 grasses and vegetation and some of the C3 grasses are being replaced by C4 grasses and so in feeding they were getting the bulk but not the nutrition, so that would weaken them. Plus other animals too were feeding on them and that’s thought to be one possibility. Once you get a population down where they don’t have enough variety for breeding, then they fall prey to predators and a lot of things [like] disease.

Thank you.

[Lightly edited for readability.]