August 2017

Many years ago, I received an angry note from a young returned missionary, husband, and father, a graduate student in a distant state, denouncing the Church for lying about its history and denouncing me for my alleged role in defending those lies.

An exchange ensued. I tried to persuade him that he was wrong. He remained hostile, and it was easy to see that he was deeply troubled.

Abruptly, his messages stopped.

After a while, oddly uneasy about the silence and following several unanswered notes inquiring whether he was alright, I called the Institute director at the school where he’d been studying.

My worries were confirmed in the worst possible way. The young man, I was told, had killed himself with a shotgun a month or two before, just about the time our correspondence had ended.

Obviously, I was horrified. I wondered what, if anything, I might have done to help. I read and reread our correspondence, looking for signs that I should have picked up.

Now, I don’t know exactly what went into this young man’s decision to end his life, and to do it in such a horrible way. There may have been—there probably were—many factors involved. But I’m reasonably confident that his loss of faith and his bitter alienation from the Church contributed.

Obviously, most who leave Mormonism don’t take their own lives. Some glide painlessly out. I understand them. A pay increase, an extra day each week, and no meetings! The attractions are obvious.

Others, however, go through periods—whether brief or lifelong—of resentful anger. Important relationships with neighbors, children, parents, spouses, and extended family sometimes rupture in the wake of what we believers call “apostasy.” Often, they suffer from depression. A world charged with eternal meaning, and relationships suffused with cosmic significance, can become an abyss of sheer pointlessness, culminating in oblivion.

These things matter.

I recently received a note from a psychiatrist in Georgia, in my judgment himself a victim of his loss of faith, begging me to persuade Church leaders to stop their “lying.” He claims—and I have no reason to doubt him—that he deals with the consequences of those alleged lies in his own practice, when fellow disaffected Latter-day Saints seek him out for help.

I’m not a professional counselor—though, as I’ve gained experience over my uncountable decades, I’ve come to recognize more and more the help that such counselors can provide. But I believe that there’s an even more fundamental cure for the emotional and psychological turmoil caused by disillusionment and loss of faith.

That cure is a return to faith and trust.

“Unyielding Despair”

I don’t wonder at the havoc that complete loss of faith can induce in sensitive souls.

Listen to what the outspokenly atheistic philosopher Bertrand Russell says in his 1903 essay “A Free Man’s Worship”:

That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the débris of a universe in ruins — all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

Somehow, “unyielding despair” doesn’t seem a very promising basis for a happy life.

The French philosopher and writer Albert Camus published a famous 1942 collection of essays titled The Myth of Sisyphus in which he grappled with the view that we’re just a pointless combination of chemicals, with what he labeled the “absurdity” of the human situation:

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem,” he wrote, “and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.”

A robust faith, like the loss of one, makes a difference.

Health

For one thing, it apparently makes people healthier.

“Neither in my private life nor in my writings,” Sigmund Freud wrote in a 1938 letter to Charles Singer, “have I ever made a secret of being an out-and-out unbeliever.” Indeed, he wrote to Marie Bonaparte, “I regard myself as one of the most dangerous enemies of religion.”

And, in fact, he was plainly obsessed with religion, treating it repeatedly in such books as Totem and Taboo (1913), The Future of an Illusion (1927), Civilization and Its Discontents, (1930) and Moses and Monotheism (1938), comparing the “wishful illusions” of religion to “blissful hallucinatory confusion,” religious teachings to “neurotic relics,” and religion itself to “a universal obsessive compulsive neurosis” and “a childhood neurosis.”

And this theme of religious faith as psychological defect, a sickness of the mind, remains popular among modern atheists, too. “Faith,” declares Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (1976), “seems to me to qualify as a kind of mental illness.” “It is difficult to imagine a set of beliefs more suggestive of mental illness,” agrees Sam Harris in his 2004 bestseller The End of Faith, “than those that lie at the heart of many of our religious traditions.”

So, are religious people by definition “sick”? Mentally ill? Is atheism healthier than faith?

For several decades, Armand Nicholi, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School as well as the editor and co-author of the Harvard Guide to Psychiatry, has taught an honors course for Harvard College and Harvard Medical School that’s focused on Freud and the great Christian writer C.S. Lewis. Although the two never actually met, Nicholi puts them in dialogue and comparison with each other. (This isn’t as arbitrary as it might seem: Lewis, an atheist for half his life, was well aware of Freud’s writings.)

In 2002, based upon that course, Nicholi published The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex and the Meaning of Life. It’s a fascinating study, and one could easily argue from it that Lewis led a healthier and happier life than did Freud.

Via such publications as Is Religion Good for Your Health: The Effects of Religion on Physical and Mental Health (1997), his Handbook of Religion and Mental Health (1998), and his editorship of the Oxford Handbook of Religion and Health (2012), Harold Koenig, a psychiatrist on the faculty of Duke University, has established himself as a premier authority in this area. He and his collaborators argue that religious involvement is correlated with better mental health in the areas of depression, substance abuse and suicide, and, somewhat less certainly, with better results in the treatment of stress-related disorders and dementia.

Moreover, according to Tyler VanderWeele, professor of epidemiology at Harvard University, recent research published by himself and his colleagues in various top-tier medical journals confirms the links that previous scientific investigation had identified between attendance at religious services and enhanced health. Regular attendance is associated, for example, with “a roughly 30 percent reduction in mortality over 16 years of follow-up; a five-fold reduction in the likelihood of suicide; and a 30 percent reduction in the incidence of depression,” VanderWeele writes.[1]

But the apparent blessings don’t end there: Regular participation in communal religious worship appears to be associated with “greater likelihood of healthy social relationships and stable marriages; an increased sense of meaning in life; higher life satisfaction; an expansion of one’s social network; and more charitable giving, volunteering, and civic engagement,” says VanderWeele.

One might perhaps conclude that it’s the social support afforded by religious participation that confers such benefits. VanderWeele, however, says that social support accounts for only about 20-30 percent of the measured results. The self-discipline encouraged by religious faith and the optimistic worldview that it supports also appear to be important contributing factors to physical health and longevity.

Of course, none of this proves religious claims are true. But it does strongly suggest that faith isn’t an illness, and that, on that point at least, Freud and his followers are wrong.

Persisting in the Freudian tradition, however, one standard British psychiatric textbook from the mid-20th century declares that religion is for “the hesitant, the guilt-ridden, the excessively timid, those lacking clear convictions with which to face life.”

In his 2009 book Is Faith Delusion? Why Religion is Good for Your Health, Dr. Andrew Sims, former president of the United Kingdom’s Royal College of Psychiatrists and professor of psychiatry at the University of Leeds, contends, on the basis of his own psychiatric practice as well as a large number of scientific studies, that “people with religious belief, rather than being timid and lacking clear convictions, have a greater sense of direction and feeling of independence from control.” Indeed, one of the major themes of his book is that “religious belief tends to be associated with better health, both physical and mental.”

“The advantageous effect of religious belief and spirituality on mental and physical health is one of the best-kept secrets in psychiatry, and medicine generally,” he writes. “If the findings of the huge volume of research on this topic had gone in the opposite direction and it had been found that religion damages your mental health, it would have been front-page news in every newspaper in the land!”

Moreover, Sims contends, “churches are almost the only element in society to have offered considerate, caring, long-lasting and self-sacrificing support to the mentally ill,” which is one of the reasons why “religious involvement results in a better outcome from a range of illnesses, both mental and physical.”

In the majority of scientific studies, Sims summarizes, religious involvement correlates with enhanced well-being, happiness and life-satisfaction; greater hope and optimism, even when facing serious diseases, such as breast cancer; a stronger sense of purpose and meaning in life; higher self-esteem; better responses to bereavement; greater social support; less loneliness; lower rates of depression and faster recovery from depression; reduced rates of suicide; decreased anxiety; better coping with stress; less psychosis and fewer psychotic tendencies; lower rates of alcohol and drug abuse; less delinquency and criminal activity; and greater marital stability and satisfaction. A strong faith and the positive relationships and thinking associated with church membership fortify the immune system, “thus reducing the risk of cancer, improving general health and protecting the cardiovascular system.”

“When looking at the overall effects of religious belief and practice on whole populations,” he writes, “there is substantial evidence that religion is highly beneficial for all areas of health, and especially mental health.”

Indeed, correlations between religious faith and improved well-being “typically equal or exceed correlations between well-being and other psychosocial variables, such as social support.” And, he adds, this substantial assertion is “comprehensively attested to by a large amount of evidence.”

“In one well-conducted study,” Sims reports, “almost 3,000 women who regularly attended church services were assessed for health status, social support and habits. When they were followed up 28 years later, their mortality over that period was found to be more than a third less than the general population.”

Furthermore, “An inverse relationship has been found between religious involvement and suicidal behaviour in 84 per cent of 68 studies. That is, those with religious belief and practice are less likely to kill themselves. This association is also found for attempted suicide; believers are less likely to take overdose or use other methods of self-harm.”

“The nagging question we are left with is, why is this important information” — “epidemiological medicine’s best-kept secret,” he calls it — “not better known?”

If it were anything other than religious belief or spirituality resulting in such beneficial outcomes for health, the media would trumpet it and governments and health care organizations would be rushing to implement its practice.

One of the most interesting and provocative social analysts in America today is Arthur Brooks, currently president of the American Enterprise Institute. In 2004, Dr. Brooks published Who Really Cares, in which he notes that scores of studies have demonstrated that believers live longer, healthier lives. People who never attend religious services are at the highest risk of early death, while those who attend more than once each week have the lowest such risk. At age 20, this translates into a seven-year difference in average life expectancy. Religious people heal more quickly from serious diseases and surgeries. Remarkably, too, in victims of HIV four years after diagnosis, those who’ve become religious show noticeably lower rates of disease progression than do their unbelieving fellow-sufferers.

In addition, as many studies have shown, religious people tend to be much happier and more satisfied than the irreligious. They cope better with crises. They recover faster from divorce, bereavement and being fired. They enjoy higher rates of marital stability and marital satisfaction. They’re less likely to be depressed, to become alcoholics or drug addicts, to commit suicide or to commit crimes. Elderly religious people are much less likely to be depressed, but if they are, they’re less so than their unbelieving counterparts.

In 2008, Brooks published a book titled Gross National Happiness. In it, drawing on the relevant sociological literature, he presents his case for what makes us happy and what doesn’t.

Religious people of all faiths are, on average, markedly happier than secularists, and this is true even when wealth, age and education are taken into account. In one major survey, 23 percent of secularists reported being “very happy” with their lives, versus 43 percent of religious respondents. Believers are a third more likely to express optimism about the future. Unbelievers are almost twice as likely as the religious to say, “I’m inclined to feel I’m a failure.”

In 2004, 36 percent of those who prayed every day said they were “very happy,” while only 21 percent of those who never prayed said so.

Data from 1998 reveal that people who were certain that God exists were a third more likely to describe themselves as “very happy” than those who denied his existence. Curiously, agnostics were more gloomy than atheists; only 12 percent of agnostics surveyed claimed to be very happy. People who asserted that there was “little truth in any religion” were roughly half as likely to assert a high degree of happiness as those who believed that religion contains significant truth.

Believers in life after death are about a third more likely than nonbelievers to call themselves “very happy.” By contrast, people who say that we don’t survive death are three-quarters more likely to say that they aren’t very happy.

Correcting for other cultural factors and comparing apples with apples, people who live in religious communities also fare better financially than do those who live in relatively secular communities. Brooks cites an economist who investigated the effect on one’s income when others in one’s community are religiously active. For instance, he measured how the church attendance of Italian-American Catholics affected the incomes of African-American Protestants in the same neighborhood. His conclusion? The more your neighbors go to church, the more you will tend to prosper. This is probably because of the cultural benefits that accrue to a community as a whole when a significant proportion of the community follows typical religious standards: There’s likely, for example, to be less divorce and drug abuse—both of which cause economic woes. And such influence in a community attracts like-minded people into a neighborhood, thus improving it further.

An advocate of greater secularism might concede that religious fantasies provide a helpful crutch for stupid, ignorant and/or irrational people, whereas better educated and more honest unbelievers face reality without such comfort.

A 2004 study, however, showed that religious adults were a third less likely than secular adults to lack a high school diploma, and a third more likely to have at least one college degree. Given two people, one of whom has a college degree and one of whom doesn’t, but who earn the same salary and are identical in age, gender, race and political views, the college graduate will be 7 percent more likely to be a churchgoer.

Secularizing writers often like to imagine how much better the world would be without religion. They should pray that they don’t get their wish.

How Shall We Live?

Several years ago, I read some heartfelt online advice from an atheist.

“Life is a one-time roller coaster ride,” he said.

Revel in it. Feel the warm sun on your skin and the cool wind in your hair. Feel the climb up, and take in the rides to the bottom. Don’t spend the entire experience preparing and fretting for what others in the line told you about the exit and what they think comes after, otherwise you will miss the entire experience.

I have little doubt that his advice was sincere. But it’s also misdirected.

There’s no reason to suppose that typical religious believers feel the warm sun and the cool air less than unbelievers do. They’re not exempt from the climbs up and the sometimes terrifying rides down.

And, no matter how devout they may be, there’s no evidence that most believers devote so much time preparing for the next life, and so much energy fretting about it, that they miss “the entire experience” of this one.

In view of the evidence I’ve cited from Arthur Brooks, that online atheist would serve his readers better if he sought to build their faith rather than encouraging them to abandon it. Although mortal life is indeed a roller coaster ride, he shouldn’t be urging them to ignore the fact that when it ends, they’ll all need to pass through the exit.

Religious believers are convinced that there is an unfathomably vast world out there beyond the exit gate for this particular ride. To continue the poster’s metaphor, those who have come to the amusement park with tickets for other attractions, money to buy food when it’s lunchtime and jackets to wear in the evening will be able to enjoy much more than just the one feature.

They’re going to have a better time than those who were focused so intently on enjoying their “one time roller coaster ride” that, at its end, they lack the resources or ability to enjoy anything else.

There is no evidence that those who think of the future miss out altogether on the present. In fact, evidence suggests the contrary: Religious believers, if they’re correct, get a better future. In any case, they apparently get a better today.

“I’m an atheist,” the late actress Katherine Hepburn once told an interviewer, “and that’s it. I believe there’s nothing we can know except that we should be kind to each other and do what we can for each other.”

Plainly, atheists can be, and often are, good people. It’s wonderful that Katherine Hepburn knew those things. I believe that she did know them; I hope that she acted accordingly. But how did she know them? It’s one thing to believe in moral principles; it’s quite another to be able to justify them, to give an account of their source. And this seems to me a particular problem for atheists.

“Morality,” writes the evolutionary atheist philosopher Michael Ruse,

or more strictly our belief in morality, is merely an adaptation put in place to further our reproductive ends. Hence the basis of ethics does not lie in God’s will — or in the metaphysical roots of evolution or any other part of the framework of the Universe. In an important sense, ethics as we understand it is an illusion fobbed off on us by our genes to get us to cooperate. It is without external grounding. Ethics is produced by evolution but is not justified by it.

Once I’ve recognized that morality is an illusion, though, why should I feel bound by it — especially when I can safely ignore it?

“We are survival machines,” says the British biologist and vocal “New Atheist” Richard Dawkins, nothing more than “robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes.”

“What natural selection favors,” writes Dawkins,

is rules of thumb, which work in practice to promote the genes that built them. Rules of thumb, by their nature, sometimes misfire. In a bird’s brain, the rule ‘Look after small squawking things in your nest, and drop food into their red gapes,’ typically has the effect of preserving the genes that built the rule, because the squawking, gaping objects in an adult bird’s nest are normally its own offspring. The rule misfires if another baby bird somehow gets into the nest, a circumstance that is positively engineered by cuckoos. Could it be that our Good Samaritan urges are misfiring, analogous to the misfiring of a reed warbler’s parental instincts when it works itself to the bone for a young cuckoo? An even closer analogy is the human urge to adopt a child.

But does adoption—or contributing to relief for unrelated poor people in distant countries, or risking one’s life to save a stranger—really represent mere evolutionary error?

To his credit, Dawkins himself recoils from the idea. He calls such acts “precious mistakes.” But why are they “precious”? What does that mean beyond the mere fact that he likes them, as he might like broccoli or the Beach Boys?

“The universe that we observe,” he’s also written, “has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.”

On what objective grounds, if any, can someone holding this view say that failure to help a child or fight Third World hunger is “wrong”? On what basis, even, can such a person condemn murder, rape or child abuse? If somebody else endorses them, on what basis can a Dawkins disagree? The Nazis regarded killing Jews and Gypsies and enslaving Slavs as good things. Are these only matters of opinion?

Thirty years after first seeing it, I still vividly remember the chilling scene in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1986 film version of Verdi’s opera Otello in which Iago sings his very Darwinian creed:

I believe in a cruel God

who created me in his image

and who in fury I name.

From the very vileness of a germ

or an atom, vile was I born.

I am a wretch because I am a man,

and I feel within me the primeval slime.

Yes! This is my creed!

I believe with a heart as steadfast

as that of the widow in church,

that the evil I think

and that which I perform

I think and do by destiny’s decree.

I believe the just man to be a mocking actor

in face and heart;

that all his being is a lie,

tear, kiss, glance,

sacrifice and honour.

And I believe man the sport of evil fate

from the germ of the cradle

to the worm of the grave.

After all this mockery then comes Death.

And then?… And then?

Death is nothingness,

heaven an old wives’ tale.

On what rational grounds can a follower of Richard Dawkins demonstrate Iago’s lethal amorality to be “wrong”?

Faith or non-faith. We cannot escape the decision. Not to decide is to decide. It will deeply mark how we live our lives. To live as an agnostic is, practically speaking, typically to live as an atheist.

Benefits to Society

By just about any measure, Western society has grown much more secular in recent decades. This is likely to have consequences. It makes a difference.

For as long as I can remember, nonreligious people have assured me that, while I’m supposedly focused on some sort of illusory “pie in the sky when I die” and on “saving” others from mythical sufferings in a fairy-tale afterlife, they’re devoted to making life in this world, on this planet, tangibly better for everybody.

In my particular case, of course, the critics may be right. They’re very likely far better people than I am—more charitable, kinder, more concerned for their fellow humans. However, unless they actually supply evidence to demonstrate it, Arthur Brooks’s 2006 volume, Who Really Cares, has made it much, much harder for secularists to preen themselves, as a class, on their superior compassion.

Brooks has studied patterns in charitable giving and service for many years and is widely recognized as perhaps the pre-eminent authority on the subject. Still, he even he reports that he’s been surprised by what he’s found.

Religious people, it turns out, give more to charity than do nonreligious people. They donate more money—and not merely to their churches, synagogues, temples and mosques.

They’re more likely to give money to family and friends, and, when they do, to give larger amounts. They’re far more likely to give food or money to the homeless and to donate blood, and even to return money from a cashier’s mistake or to express empathy for the less fortunate. It’s 15 percent more likely that churchgoing Europeans will volunteer for nonreligious charities than their secular compatriots. Even non-churchgoers, if they were raised in religious households, are more likely to donate to charity than those who were not.

Not surprisingly, private charity in ever-more-secular Europe has plummeted—to the point, in some areas, almost of extinction. Brooks, who also argues that charitable giving is essential to a strong economy, points to polling data suggesting that Europeans are, according to their own reports, less happy with their lives than Americans are, and suggests that their unhappiness may be connected with their low rates of charity and volunteerism. Humans feel better when they give.

91 percent of American religious conservatives give to charitable causes, compared to only 67 percent of those who identify themselves as secular liberals. Those who pray daily are 30 percent more likely to give to charity than people who never pray. In Europe, too, churchgoers volunteer 30 percent more often, overall, than non-churchgoers. Even controlling for other factors, 83 percent of religious Americans will volunteer in any given year, while, among secular French people, only 27 percent will.

As befits a premier social scientist, Brooks employs multiple streams of contemporary statistical data to form his judgments. However, the historical record also seems to support the general conclusions of his very important book:

The respected and prolific sociologist Rodney Stark, in an insightful study of The Rise of Christianity (Princeton, 1996), has shown that the superior charity of the ancient Christians was a vital factor in the rapid growth of the early Christian movement. And, as an examination of the surviving sources demonstrates, even the pagans recognized that. “The impious Galileans support not only their poor, but ours as well,” lamented the fourth-century pagan Roman Emperor Julian. “Everyone can see that our people lack aid from us.”

“Religion is the opiate of the people,” Karl Marx famously complained. Elsewhere, he remarked that, while “philosophers have said that the purpose of philosophy is to understand the world, the purpose is to change it.” Religion, in his view, was a distraction from the real business of making this world a better place. Unfortunately for Marx’s thesis, though (and, even more so, for those who had to live through the 20th century), the millennium that just closed was heavily influenced at its end by Marxism and by a related ideology that went under the names of fascism and “National Socialism” or Nazism. We now have quite graphic evidence of exactly how such theories tend to “change the world.”

“We must rid ourselves once and for all,” wrote the Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky in his 1930 book The Russian Revolution, “of the Quaker-Papist babble about the sanctity of human life.” And they did. Scholarly estimates of atheistic communism’s murders over the past century range from roughly 40.5 million to nearly 260 million.

But Marxism merely followed a path blazed for it by the French Revolution’s anti-Catholic and anti-Christian “Reign of Terror.” Citizen Robespierre and his associates, determined to establish a “Cult of Reason,” killed many thousands of innocent people — sometimes cleanly, via the guillotine, but often through disgusting and obscene torture.

In 1983, the great 1970 Nobel Literature laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (d. 2008), fearless chronicler of the crimes of Soviet communism, delivered a lecture sometimes titled “Godlessness: The First Step to the Gulag.”[2] The opening lines of that address deserve full quotation:

More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

What is more, the events of the Russian Revolution can only be understood now, at the end of the century, against the background of what has since occurred in the rest of the world. What emerges here is a process of universal significance. And if I were called upon to identify briefly the principal trait of the entire 20th century, here too, I would be unable to find anything more precise and pithy than to repeat once again: Men have forgotten God.

Even when contrasted with the soft secularism that’s come to dominate Europe, perhaps Canada, and certain portions of the American elite, and even though religious people can undoubtedly do much more and much better than they’re doing now, believers fare pretty well.

In America’s Blessings: How Religion Benefits Everyone, Including Atheists, Rodney Stark draws a number of striking conclusions after surveying the relevant data. Some of this will repeat what I’ve already said. Which is fine. I want it to be remembered.

Regardless of their age, Stark says, religious people are much less likely to commit crimes. Accordingly, the higher a city’s church membership rate, the lower its rates of burglary, larceny, robbery, assault, rape, sexually transmitted disease and homicide. In a cleverly designed test at Pepperdine University, a disappointing 45 percent of weekly church attenders turned out to be honest, but that was still more than three times the 13 percent rating of non-attenders.

Curiously, however, although nearly 250 studies conducted between 1944 and 2010 showed clear evidence that religion helps to reduce delinquency, deviation and crime, virtually no standard textbooks on criminology so much as mention “religion” in their indexes. But the fact remains, says Stark, that “All Americans are safer and their property more secure because this is such a religious nation.”

Religious people are the primary source of charitable funds not only for religious causes but for secular philanthropies that benefit all victims of distress and misfortune. They are far more likely to volunteer their time for programs that benefit society and to be active in civic matters.

As I’ve already noted, fashionable schools of psychology have long taught that religion either contributes to mental illness or is itself a dangerous species of psychopathology. But the evidence, says Professor Stark, “shows overwhelmingly that religion protects against mental illness.” For example, persons with strong, conservative religious beliefs are less depressed than those with weak and loose religious beliefs. “They are happier, less neurotic, and far less likely to commit suicide.”

Religious people are more likely to marry and to stay married than their irreligious counterparts, and, on the whole, they express greater satisfaction with their marriages and their spouses. They are far less likely to have extramarital affairs. In addition, “Religious husbands are substantially less likely to abuse their wives or children.” Mother-child relationships are stronger for frequent church attenders than for those who rarely if ever go to church, and for mothers and children who regard religion as very important, they’re stronger than for those church-attenders who don’t value religion so highly. Precisely the same thing holds for the level of satisfaction of teenagers with their families. Greater religiosity means higher satisfaction.

Strongly religious persons seem, all other things being equal, to enjoy reduced risks of heart disease, strokes and high blood pressure or hypertension than those who are less religious, and seem to recover better from coronary artery bypass surgery. The average life expectancy of religious Americans is more than seven years longer than that of the irreligious. Moreover, “a very substantial difference remains” even when the effects of “clean living” have been factored out.

Religious students tend to get better grades than do their non-religious counterparts, as well as to score higher on all standardized achievement tests. They are less likely to be expelled or suspended or to drop out of school, and are more likely to do their homework.

Religious Americans are also, on average, more successful in their careers than are the irreligious. They obtain better jobs and are less likely to find themselves unemployed or on welfare.

Committed religious believers are less likely to patronize astrologers or to believe in the occult and the paranormal than are nonbelievers. On the other hand, though they’re often caricatured as ignorant, churchgoers are more likely to read, to patronize the arts and to enjoy classical music than are non-churchgoers.

“Translated into comparisons with Western European nations,” writes Professor Stark, addressing an American audience, “we enjoy far lower crime rates, much higher levels of charitable giving, better health, stronger marriages, and less suicide, to note only a few of our benefits from being an unusually religious nation.”

None of these facts proves religious claims true, of course. But they certainly undermine the old accusation that religion is unhealthy and antisocial.

As Harvard’s Robert Putnam expresses it in his famous book Bowling Alone, believing churchgoers are “much more likely than other persons to visit friends, to entertain at home, to attend club meetings, and to belong to sports groups; professional and academic societies; school service groups; youth groups; service clubs; hobby or garden clubs; literary, art, discussion, and study groups; school fraternities and sororities; farm organizations; political clubs; nationality groups; and other miscellaneous groups.”

“So,” asks Mary Eberstadt in her book How the West Really Lost God, “is it in society’s interest to encourage Christian practice?” She then provides her own response. “The answer is: only so far as it is in society’s interest to encourage quality of life, enhanced health, happiness, coping, less crime, less depression, and other such benefits associated with religious involvement.”

Meaning

On one understanding, life arose, simply and exclusively—but, to current scientific understanding, still quite mysteriously—from chance events in a warm little pond or, perhaps, near a volcanic vent deep in an early sea. We humans emerged billions of years thereafter via cellular mutations in the line of apelike organisms who are our ancestors.

One way of looking at this evolutionary history—that of Sam Harris, for example—concludes that it leaves no room for purpose or even freedom of the human will. All is the result of natural processes that we call random only because we don’t know all the factors involved; if we knew them all and possessed enough calculating power, we would be able to see that it was entirely inevitable. And, of course, there’s no room for the soul’s survival after death because there’s no soul. We’re, essentially, temporary cell colonies, doomed to annihilation.

But this viewpoint seems to entail some potentially disquieting things: If, for instance, our thoughts are merely neurochemical brain events set in motion by a deterministic process that goes all the way back to the Big Bang (perhaps with some quantum uncertainty tossed in to make it a bit less rigid but no less pointless), what can it possibly mean to say that our thoughts are “about” something? Other bodily functions—digestion, respiration or blood circulation, for example—aren’t “about” anything. They simply “are.” And what reason do we have to trust such “thoughts” regarding the nature and meaning of the universe? If our brains evolved to help us survive and reproduce—which is what the Darwinian principle of survival of the fittest strongly suggests—how can we be sure that they’re reliable beyond those limited functions?

If “meaning” of any sort is to survive, it’s not clear that atheistic naturalism can deliver it. These things make a difference.

Trials and Death

During my mission in Switzerland, we showed the German version of Man’s Search for Happiness so often that I think I still have the German script memorized. “Die grösste Prüfung deines Lebens,” it says at one point, “hast du am Grabe eines deiner Lieben zu bestehen.” “The greatest test of your life will be at the grave of one of your loved ones.”

As a young man, I knew this in theory. I can now bear witness to it from personal experience.

According to an early story, a despairing mother whose little boy had died once came to the Buddha, begging him to restore her son to life. The Buddha told her to go about the town collecting mustard seeds. But she was to do so only from houses in which nobody had ever died.

Hopeful, she set about her task. But she found only disappointment, because each house had experienced death. Finally, she returned to the Buddha without a single mustard seed. Now she understood that death was universal and inescapable. And, though still sorrowful, she had come to accept it.

The simple, unavoidable fact is that we all will die. And all those whom we love, and every thing that we love, will also die. All earthly relationships end in death, if not before.

When you hear the funeral bells ring, the English poet John Donne said, “send not to know for whom the bell tolls: It tolls for thee.” And, he might have added, for thy family and friends.

Nevertheless, many of us energetically (and fairly successfully) try to avoid reflecting on our mortality. “I’m not afraid to die,” Woody Allen said. “I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

But Mr. Allen has no choice. He’ll be there, like it or not.

Every day, each of us draws nearer to the end. In the words of the unexpected Nobel laureate Bob Dylan, “He not busy being born is busy dying.”

Is this life all there is? Are all the love, hopes, attainments and talents of an individual nothing more than a random, transient and ultimately meaningless collection of neurochemical impulses?

There are, essentially, only two possible answers to this question. One is eloquently summarized by Shakespeare’s Macbeth, for whom the close of mortal life was the absolute and irrevocable end. Upon hearing of his wife’s suicide, Macbeth exclaims:

All our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.[3]

Others respond with less anger: “Apatheism” is the witty term coined for the complete indifference to great issues of faith and religion that’s fashionable in some circles.

“If there were a God,” a supremely complacent atheist once told me online, “I think (s)he’d enjoy hanging out with me — perhaps sipping on a fine Merlot under the night sky while devising a grand unified theory.”

“If you live in this very moment,” another atheist wrote to me a year later, “you’ll find happiness. You realize that life isn’t about getting to the shore. It’s about enjoying the feel of the water glide against your skin, feeling the power in your arms as you systematically push water behind you, deeply breathing the fresh salty air, feeling a moment of awe as you turn your head and see the sunset, and feeling the love that you share with your fellow swimmers. This life is a precious thing in and of itself. There may be something beyond it, there may not. But this life is wonderful enough.”

I understand his attitude; things can be very good indeed for those who win life’s lottery. But it hasn’t been so good for many, and there’s nobody for whom it’s always grand.

Most of us don’t die suddenly, for example, passing painlessly from robust health into oblivion while accompanied by a first-rate string quartet. We commonly endure physical deterioration and mental decline.

What’s the difference between a good long life and a fine meal? Fine meals end with dessert.

And for too many, this follows lives of frustration, hunger, humiliation, pain, injustice and oppression.

Life “in this moment” can be hellish.

Perhaps 40 percent of the population of classical Athens were slaves. In ancient wars, husbands and fathers were often put to the sword; their women and children were enslaved without rights. But urban slaves were the lucky ones. Others went to the Athenian silver mines, where, rarely seeing the sun, they were harshly beaten, starved and worked to death.

Nearby Sparta depended upon a population of “helots,” fellow Greeks—seven for every citizen—who farmed the city’s lands under continual military occupation. Sparta’s teenagers honed their military skills by roaming in gangs through the helots’ settlements, terrorizing them and destroying their hovels. And every year, somewhat in the spirit of The Hunger Games, Sparta’s rulers declared ritual war on the helots, murdering anybody who showed signs of leadership.

Such was life for many in classical Greece, at the fountainhead of Western civilization. And conditions surely weren’t better under the ancient Assyrians or Babylonians, or the medieval Huns and Mongols.

While comfortable people often observe that money doesn’t bring happiness, poverty and hunger make happiness very elusive. According to the United Nations World Food Programme, one person in nine is chronically undernourished, therefore lacking the energy and mental acuity needed for a full life. One quarter of those in sub-Saharan Africa suffer from malnutrition. More than 3 million children under the age of 5 die from malnourishment each year. And I’ve said nothing about the cruelty of oppressive armies and murderous tyrants.

In his 1870 Grammar of Assent, John Henry Newman quotes the words of a dying factory girl from a then-popular story:

I think if this should be the end of all, and if all I have been born for is just to work my heart and life away, and to sicken in this (dreary) place, with those millstones in my ears for ever, until I could scream out for them to stop and let me have a little piece of quiet, and with the fluff filling my lungs, until I thirst to death for one long deep breath of the clear air, and my mother gone, and I never able to tell her again how I loved her, and of all my troubles, — I think, if this life is the end, and there is no God to wipe away all tears from all eyes, I could go mad!

Historically, most of the human race has lived like the dying factory girl, not “sipping a fine Merlot under the night sky.” Beyond a relatively small number of privileged places, her story typifies much human experience even today.

For many, life isn’t wonderful. And, for virtually all, it’s punctuated (and often ended) by moments of terrible pain and acute sorrow. If there’s no redemptive life after death, viruses, child murderers, gross physical deformities and random accidents—not to mention history’s Hitlers and Stalins—have had the last word in billions of lives, and will continue to have it.

None of these sad realities proves the existence of God, of course, or of life after death or ultimate justice. In fact, quite understandably, many see in them a powerful argument against God. Surely, though, they illustrate why the hope for eternal joy and compensation is so deeply important.

“In light of heaven,” said Mother Teresa, who was well aware of poverty and human agony, “the worst suffering on Earth, a life full of the most atrocious tortures on Earth, will be seen to be no more serious than one night in an inconvenient hotel.”

If she’s right, that’s fabulous news for everybody who has ever lived.

Even successful lives are often marred by terrible pain. Consider, for example, the cases of three eminent scientists:

The obvious one, I suppose, is Stephen Hawking, widely considered one of the foremost theoretical physicists since Einstein. His brilliant mind is trapped in a body twisted and ruined by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. He communicates now via a speech device activated by a single muscle in his cheek.

Another is Charles Darwin, surely among the most important scientists who have ever lived. His was an extraordinarily accomplished and influential life, and his fame is imperishable. But two of the Darwins’ children died in infancy, and he worried deeply every time any of the others was sick. Then his beloved oldest daughter, Annie, became ill. When she died just after turning ten, Darwin, already probably an agnostic, was so overcome with grief that he couldn’t attend her burial.

Finally, there is Max Planck, originator of quantum theory, winner of the 1918 Nobel Prize for Physics. The elite German scientific institution known as the Max Planck Society is named for him, as are its 83 prestigious Max Planck Institutes. In physics, Planck time is the unit of time required for light to travel a distance of one Planck length in a vacuum, expressed in a system of natural units known as Planck units. Planck’s constant is a central concept in quantum mechanics.

Max Planck died in Göttingen in 1947, nearly ninety years old, laden with honors.

But what happened along the way? In 1909, Planck’s wife Marie died suddenly after twenty-two years of happy marriage. In 1914, during World War One, his son Erwin was taken prisoner by the French and his son Karl was killed in action. In 1917, his daughter Grete died while giving birth to her first child. In 1919, his daughter Emma died in childbirth. In 1944, his house was completely destroyed by fire following an Allied bombing raid. In January 1945, Erwin, to whom Planck had been particularly close, was sentenced to death by the Nazis for his participation in the July 1944 assassination plot against Hitler. Erwin was executed on 23 January 1945, just three months before the end of World War Two.

Another issue: Human potential is never fully realized in mortality. Too often, in fact, it’s scarcely realized at all.

Consider Ludwig van Beethoven, certainly among the foremost composers of all time, perhaps indeed the very greatest.

A prodigy born in 1770 to a commonplace court musician and a chambermaid who died of tuberculosis when he was 16, he began to perform professionally at the age of 10. Thereafter, he received no further education except in music.

His health was terrible almost from the start. Although some have suspected that he brought his illnesses on himself through alcoholism and immorality, this seems to be false. He already suffered from chronic colic and diarrhea, and from frequent fevers and septic abscesses, by his 21st birthday.

When he was only 27, he began to go deaf. Experts now think that he suffered from otosclerosis, an abnormal sponge-like bone growth in the middle ear whose cause is unknown (though it may be genetically transmitted). This growth prevents the ear—and usually both ears—from vibrating in response to sound waves, which is essential to being able to hear. Even today, the disease is progressive and incurable.

Well before his 30th birthday, Beethoven suffered from incessant ringing and whistling in his ears, and, especially in winter, from terrible earaches and headaches. By 1805, when he was in his mid-30s, he could scarcely hear wind instruments. Yet noises caused him pain; he often stuffed his ears with cotton wool, and, in 1809, he covered his head with cushions in an attempt to escape the horrific roar of Napoleon’s cannons bombarding Vienna.

By 1812, his visitors had to shout to be understood. He destroyed piano after piano, pounding upon the keys out of his desperation to hear. Five years later—when he was still only about 47—he was completely deaf and could no longer hear music at all.

His great Ninth Symphony premiered on May 7, 1824, in Vienna. He was there, standing near the conductor, but he never heard it. (You may have, but he never did. Think about that.) Reportedly, several in the orchestra wept as they played. Afterward, the contralto soloist turned him around to see the passionate applause of the audience who, seized by emotion, applauded all the louder and more visibly.

Beethoven died less than three years later, at 57, apparently from complications of jaundice, which he had contracted roughly seven years before. The autopsy revealed a ravaged, worn-out liver, and modern scholars suspect that he may have suffered for many years from an immunopathic disease called systemic lupus erythematosus, which begins in early adulthood—at about the same time, in other words, that his otosclerosis began to manifest itself—and, though it may come and go for a while, eventually becomes chronic. Its symptoms include not only liver disease but rashes, redness in the face, rheumatism, and emotional instability.

And Beethoven certainly had emotional issues. Ravaged by constant stomach pain, frustrated by his uniquely tragic combination of musical genius and deafness, he was quarrelsome, suspicious, rude, commonly in a state of rage. And, thus, he was desperately lonely. His living quarters were disorderly and often filthy. He was perpetually in debt—partly, perhaps, because he lacked basic skills in arithmetic. He never married; he couldn’t even keep servants. “Oh, God,” he begged in his journal, “may I find her at last, the woman who may strengthen me in virtue, who is permitted to be mine.” But he never did.

It’s impossible not to wonder what this musical titan might have accomplished had he been healthy, had he lived longer and had he been able to hear. It’s impossible to believe that he achieved his full potential as either a composer or, even, a human being.

Beethoven’s heart-rending biography—and many millions like his, or worse—is no argument for a future life. Perhaps, a skeptic might say, there’s no purpose to the cosmos. That’s just the way it is. We live briefly, we die meaninglessly and then our little candle is extinguished—as all light and life ultimately will be extinguished in the vast heat-death of the universe.

But it should certainly cause us to hope for a future in which wounds are healed, deep yearnings satisfied and human potential fully realized.

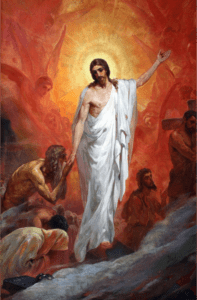

Fortunately, in the Resurrection of Christ and the Restoration of the gospel there’s a firm foundation for that hope.

Fortunately, in the Resurrection of Christ and the Restoration of the gospel there’s a firm foundation for that hope.

Be still, my soul: the hour is hast’ning on

When we shall be forever with the Lord.

When disappointment, grief, and fear are gone,

Sorrow forgot, love’s purest joys restored.

Be still, my soul: when change and tears are past

All safe and blessed we shall meet at last.

Jesus didn’t only teach theoretically about life after death. He demonstrated it. His physical resurrection and his empty tomb lift the concept of a life beyond the grave from the realm of airy speculation to that of specific, concrete history.

Jesus didn’t only teach theoretically about life after death. He demonstrated it. His physical resurrection and his empty tomb lift the concept of a life beyond the grave from the realm of airy speculation to that of specific, concrete history.

“All your losses will be made up to you in the resurrection,” testified the Prophet Joseph Smith, “provided you continue faithful. By the vision of the Almighty I have seen it.”

“Weeping may endure for a night,” says the Psalmist (30:5), “but joy cometh in the morning.”

“O death,” wrote the apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:55, “where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?”

The glorious message of Easter is that Death doesn’t win. It doesn’t have the final say.

“And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes,” testified John the Revelator, “and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away” (Revelation 21:4).

What difference does this make? It changes everything.

Endnotes

[1] See “Does Religious Participation Contribute to Human Flourishing?” at bigquestionsonline.com.

[2] www.pravoslavie.ru/47643.html

[3] Macbeth, V.5.