August 2017

Scott Gordon: So I’m really happy to have Ben Spackman as our speaker today. I’ve asked him before and he has turned me down before, so I’m happy to have him this year. Ben received a B.A. from BYU in Near Eastern Studies and an M.A. in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago. He studied General Science at City College of New York and is currently a PhD student in History of Christianity at Claremont Graduate University. He has taught volunteer Institute and seminary, and Biblical Hebrew, Book of Mormon, and New Testament at BYU. Ben has published with BYU Studies, Religious Educator, the Maxwell Institute, Interpreter, Journal of Mormon Scripture, and Religion & Politics, and blogs occasionally at Times&Seasons and Benjamin the Scribe. He has lectured at the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, the Mormon History Association, the Maxwell Institute Seminar on Mormon Culture, [and] the upcoming Sperry Symposium. He is currently writing a book on Genesis 1 for an LDS audience. With that, we’d like to welcome Ben Spackman.

Ben Spackman: Good morning. I’m glad to be here. I first got involved with FAIR in 2003 when I sent in an irate email taking issue with something they had written online. I’ll let them judge if things have improved since then.

Now, note that the title of my presentation is precursors to reading Genesis. If you’ve come expecting some kind of detailed exegesis, that’s not what I’m doing today. My current book manuscript just on Genesis chapter 1 is at 215 pages, so the detail is forthcoming.

Today I want to talk about some presuppositions we bring to reading scripture, as background to the issues of the interpretation of Genesis, opposition to evolution and young-earth creationism. The intellectual history of creationism, evolution, and the “modern synthesis” which married Mendelian genetics with Darwinian mechanisms right before the discovery of DNA is fascinating in its own right.[1] But if we look carefully at opposition to evolution on the one hand and young-earth creationism[2] on the other, we see that these are not really scientific issues. Responding to young-earth creationism as a scientific matter mistakes the symptom for the cause. Let me illustrate.

This is Kurt Wise, who has undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and Harvard in geology and paleontology.[3] Wise is a young-earth creationist, and it’s not because he is ignorant of science or the scientific method.[4] Why is he a young-earth creationist? Well, fortunately he has been very clear about this. Wise says, “Although there are scientific reasons for accepting a young earth, I am a young age creationist because that is my understanding of the Scripture….if all the evidence in the universe turns against creationism… I would still be a creationist because that is what the Word of God seems to indicate.” [5] So his being a young-earth creationist is because that is his “understanding of scripture,” and “that is what the word of God seems to indicate.”

This is Kurt Wise, who has undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and Harvard in geology and paleontology.[3] Wise is a young-earth creationist, and it’s not because he is ignorant of science or the scientific method.[4] Why is he a young-earth creationist? Well, fortunately he has been very clear about this. Wise says, “Although there are scientific reasons for accepting a young earth, I am a young age creationist because that is my understanding of the Scripture….if all the evidence in the universe turns against creationism… I would still be a creationist because that is what the Word of God seems to indicate.” [5] So his being a young-earth creationist is because that is his “understanding of scripture,” and “that is what the word of God seems to indicate.”

Wise shows that the root of young-earth creationism is not scientific evidence or reasoning. Rather, the central crux is our perception of what scripture says and what scripture means, that is, the interpretation of scripture. Talking about issues in Genesis, President Hugh B. Brown quoted Elder Anthony W. Ivins, “It is our misinterpretation of the word of the Lord that [leads] us into trouble.”[6]

So interpretation is important, and misinterpretation is a real possibility. And to set up the rest of my presentation, let’s do a little bit of LDS history. You may know that Joseph Fielding Smith was a very strong young-earth creationist. In his view, the earth was only a few thousand years old, and humans had coexisted with dinosaurs. Out of curiosity, how many of you were aware of this, by show of hands? How many of you were not aware of this, by show of hands? OK, so maybe 2/3 aware – 1/3 not. Joseph Fielding Smith argued for decades with other General Authorities who strongly disagreed with him, like James E. Talmage, John Widtsoe, B.H. Roberts,[7] Joseph Merrill, Reuben Clark, David O. McKay (see here and here), as well as prominent LDS scientists like Henry Eyring, Sr.[8] Two things have become clear to me as I read these arguments and do my other studies.

First, each of us has in our head, a black box full of presuppositions, cultural assumptions, and worldview. Into this black box goes the text of scripture, where it interacts with these unconscious things in our head, and out comes “what scripture says.” The contents of that black box vary from person to person, so people with different presuppositions and worldviews will read the exact same text, and come away with very different understandings of what the text means. For my purposes today, I’m focusing on three related topics about which we have presuppositions. That is 1) The nature of revelation 2) which comes to prophets with a small p[9] 3) which sometimes becomes scripture. I call this a black box because it’s opaque; we’re not aware we have it; we can’t see into it automatically. We tend to inherit these presuppositions without being aware of them. My goal today is to make that black box a little more transparent, so we can evaluate those presuppositions and see how they influence what we think scripture says.

Evangelical scholar John Walton says,

When we approach a text, we must be able to set our presuppositions off to the side as much as possible so that we do not impose them onto the text. It is not wrong to have presuppositions, but it is important to have a realistic grasp of what our presuppositions are so that we can assess their impact on our interpretation. Some of the traditions we carry as baggage are blind presuppositions…. We don’t even realize that they are imported into the text, and we must evaluate their relevance and truth rather than assume them to be accurate.[10]

So once we become aware that we have this black box, we can kind of open it up and unpack it and say, what are these assumptions? Are these assumptions reasonable? Do I maybe need to calibrate some of these?

Going back to our LDS history, rarely if ever did Joseph Fielding Smith or any of his interlocutors make their presuppositions explicit in these arguments back and forth over the decades. With hindsight, we can identify some of them (and that’s where the conflict really originated), but they didn’t ever do so. And so, as far as I can tell, they weren’t ever really able to pin down why exactly they disagreed. They knew what they disagreed on, but couldn’t quite figure out why. And so these arguments ended with, in essence, “well this is my reading,” “well, this is MY reading.” And it was kind of an impasse until Joseph Fielding Smith outlived everyone else.[11] These were readings, by the way. To my knowledge, no one in these discussions ever claimed revelation for their views, it was simply how they read scripture, and they read scripture differently. So that’s the first thing that stands out in reading that history.

The second thing is that the act of interpretation can and often should be a careful and conscious process, which involves things like checking the textual history to see if it has changed over time,[12] examining various kinds of context,[13] looking at the original languages or multiple translations, and so on. However, because of Mormonism’s kind of unique structure, and by this I mean we have Catholic structures (a central hierarchy that decides what the doctrine is and what scripture officially says), but we have Protestant sensibilities ( in the sense that we have a real emphasis on reading scripture, doctrine comes from scripture, scripture is the root of all these things.) The Catholic structure aspect kind of won out, and Mormons never developed the need to engage in really close reading of scripture, we never developed methods of interpretation; we never developed rules of interpretation. And so when Smith and Widtsoe were putting their interpretations up against each other, not only were they not making their presuppositions explicit, but after they each kind of put their interpretation out there, they didn’t have any way to go through and evaluate what made one interpretation stronger than another interpretation, more reasonable than another interpretation, because we simply don’t have those methods in the Church.

So although Mormons speak frequently about revelation, prophets, and scripture, we’ve never worked out any systematic approach to interpretation nor have we spent much time hammering out the various presuppositions we bring to it, collectively or individually. But there’s no reading without interpretation. From the lowest three-year-old up to Thomas Monson, there is no reading scripture without interpretation. Policy, guidance, personal decisions made after reading scripture, all are built upon interpretation, and understanding what scripture says and what it means. Once we open the black box and realize what our assumptions are about these things, we should ask, where did we get these? Are they justifiable?

So, let’s look at one.

LDS scripture includes several statements such as Jacob 4:13, “the Spirit speaketh the truth and lieth not,” and D&C 93:24, “truth is knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come.” Moreover, Joseph Smith is reported to have said, “I never told you I was perfect; but there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.”[14] With the binary rhetoric of truth vs. error, these seem to presuppose a kind of absolutist conception of revelation, wherein what the Spirit speaks and what scripture records is factually accurate and ultimately correct. This further entails what we would call a concordist and almost inerrantist approach to scripture. However, this conception of revelation that seems to be put forth by these statements is in tension or even contradiction with a number of other equally authoritative scriptures and statements. The gear of harmonious factual truth grinds loudly against the gear of recorded scripture, and our wheels are going nowhere. How, then, does “the Spirit speak truth”? In what sense should we understand Scripture inspired by the medium of God’s spirit to be truthful? And how do we make these gears mesh?

I’m going to start by demonstrating that this gear grinding, this tension is real, and that it is not merely a modern concern. And that although LDS scripture is involved, it is not uniquely an LDS issue in the sense that Christians, Jews, and even Muslims have wrestled with similar problems for hundreds or thousands of years. Why, then, does it need an LDS discussion? And so I’m going to go back and look at Jacob and D&C 93 a little bit. But most importantly, I’m going to look at two principles that together, I think, serve as a kind of automatic clutch, they allow the gears to turn without grinding.

So, the abstract principle that revelation is truthful and lacking in error runs into problems when we begin reading recorded and canonized revelation, that is, scripture. We can identify several challenges or kinds of tension to the spirit speaking only truth, without errors. And I should say at the outset, the litany of things I’m about to recite is not insurmountable, but the tools to deal with them have often been underdeveloped in an LDS context. They require us to rethink our assumptions and start talking about some of this stuff.

So, first, the Bible records an entire narrative where a divine spirit lies and misleads. 1 Kings 22 details how the kings of Israel and Judah inquire of the Lord before going to war, and the prophets give them divine assurance of victory. One last prophet is consulted, Micaiah, who assures the royals that he can only speak what the Lord tells him. He confirms victory, but upon being pressed, admits that they will actually lose badly. Micaiah describes a divine council scene in which God seeks to destroy the king, Ahab, by deceiving him into battle. The key here is v. 23, which asserts that God sent a lying spirit which deceives the prophets. Now, this story is also told in Chronicles 18, where Joseph Smith made changes to the text. This is important because it shows that Joseph Smith was aware of the passage and what it was asserting. So this is the 2 Chronicles 18 version and I have put in red the changes that Joseph Smith made.

And the Lord said, Who shall entice Ahab king of Israel, that he may go up and fall at Ramoth-gilead? And one spake saying after this manner, and another saying after that manner. Then there came out a lying spirit, and stood before the Lord, and said, I will entice him. And the Lord said unto him, Wherewith? And he said, I will go out, and be a lying spirit in the mouth of all his prophets. And the Lord said, Thou shalt entice him, and thou shalt also prevail: go out, and do even so; for all these have sinned against me. Now therefore, behold, the Lord hath put found a lying spirit in the mouth of these thy prophets, and the Lord hath spoken evil against thee.

Note that God still sends a spirit to “entice” Ahab to be destroyed, (and the Hebrew here means to “deceive, to make a fool out of someone”). God then approves of the spirit’s deception, because the people have sinned against God. The JST changes in no way support the idea that spiritual messages from God speak nothing but truth, understood in an absolute fashion. God’s purpose and will is carried out through a deceiving spirit.

A similar case might made for the binding of Isaac in Genesis 22. One could reasonably assume from God’s command to sacrifice Isaac that God desired the logical outcome of Isaac being sacrificed, namely, Isaac’s death. Readers know this is not the case. God’s intent was not at all apparent from God’s command.

Both of these Hebrew narratives suggest at best that the spirit speaks to accomplish God’s will, but does not necessarily represent it to humans transparently, in a straightforward and ultimately correct way. (And in LDS history, I think I would put both Zion’s camp and the Joseph Smith Translation into this category: Zion’s camp in the sense that they were given this command, and they thought they understood what that would mean, in the telos, in the end result of that, which was not the case. And my views on the JST are in print.[15] I’ll come back to that.)

Second, ultimate truth must be consistent with itself, but we have scripture that is internally inconsistent throughout our standard works. Exodus, for example, says to fire-roast the Passover sacrifice and not boil it, but Deuteronomy specifies that the Passover sacrifice must be boiled. Chronicles does not know what to make of this, so it combines them and it says you have to boil it in fire. Who knows how, but… Samuel attributes David’s inspiration to take a census to God, but Chronicles attributes it to Satan. The four Gospels disagree on what day Jesus was crucified, and whether the temple was cleansed at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry or the end. Paul and James both cite Genesis 15 to make points 180 degrees apart.

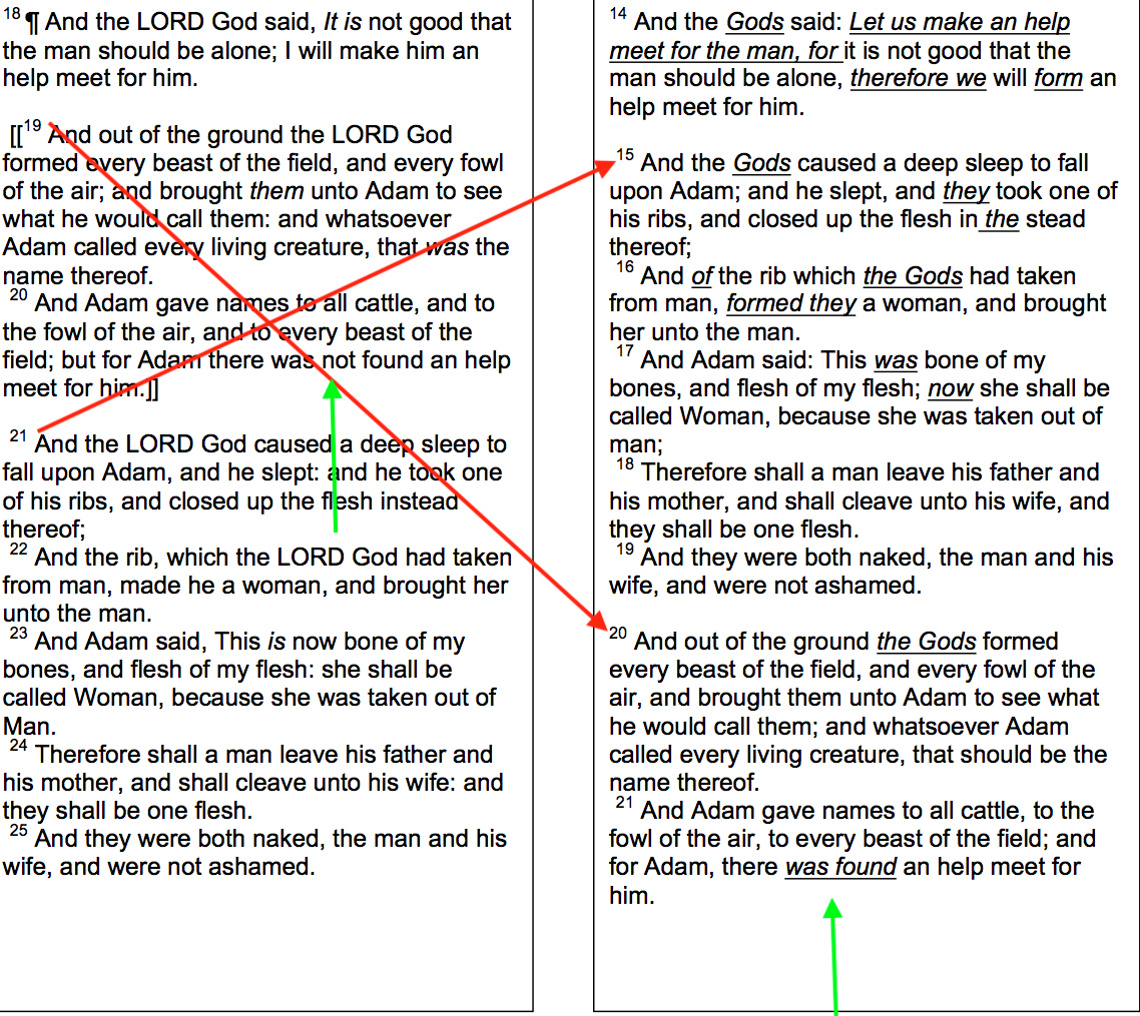

In uniquely LDS scripture, there are numerous inconsistencies between the parallel creation chapters in the books of Moses and Abraham, and many more when we compare them to Genesis, on the one hand, and the temple ritual on the other. To pick one of these, in the Genesis 2-3 section, in Genesis and Moses, there is a creation sequence where Adam comes first, followed by animals, followed by Eve as a help “meet for him.” When none of the animals has proven to be so, Eve is created, and Adam expresses some joy, that “finally, this is the right thing!” The Book of Abraham has restructured this [and you can see with the red arrows that this entire section has been rearranged] so that Eve is created with Adam, followed by all the animals. And whereas Genesis portrays Adam explicitly as not finding a “help meet for him,” which necessitates the creation of Eve, in Abraham [and this is the green arrow in the Abraham part] there is indeed found a help meet for Adam. But this is not consistent with the order in Genesis and Moses, nor with the temple.

In all of these examples, if we approach scripture with an absolute paradigm of truth vs. error and the assumption that scripture is primarily recounting history, we quickly run into problematic questions. Which Gospel is correct, which Gospel is incorrect? Which of the creation accounts is correct, which is incorrect? Does incorrect mean “not inspired”?

Third, we have scripture that is demonstrably and factually untrue. It is not true that the earth is flat and covered by a solid dome, with cosmic waters below the earth and above the dome. This is the cosmology clearly envisioned by the entirety of the Hebrew Bible, and particularly Genesis 1.

This cosmology is generally carried over into Joseph Smith’s inspired revisions in the Book of Moses and Abraham, so we cannot simply write it off as being “translated incorrectly.” This also means that young-earth creationists who claim to be putting forth a “literal” view of Genesis are, in fact, imposing a modern cosmology upon it.

Fourth, we have scripture that sets forth the idea that revelation can be extended or superseded, and there are multiple LDS examples of this happening in the D&C (which I omit here for time’s sake, but the argument is in my book). If the spirit speaks the truth, is later scripture more true? If so, what does that imply about earlier scripture? At best, it leaves earlier scripture incomplete.

I hope I have not belabored this point, but it appears that the closer one reads scripture, the more obstacles one discovers to the proposition that revelation, even modern revelation, is entirely factual, accurate, and harmonious.

Now, of the two scriptures I cited earlier, Jacob 4:13 and D&C 93, Jacob 4:13 appears to allude to Numbers 23:19, which says, “God is not a man that he should lie,” which, again, seems fairly absolute. However, the full passage appears to be more about God’s reliability in fulfilling what he has promised, not a statement about divine communication constituting unfiltered divine propositional truth.

“Truth,” by the way, in Hebrew, if you know anyone named Emmet, that is the word “truth” in Hebrew. “Truth” in Hebrew is less about propositional accuracy, and more about reliability and trustworthiness.

With D&C 93:24 “truth is knowledge of things as they are, as they were, and as they are to come.” How well does this apply to propositions and events?

Is it possible to understand this passage as knowledge of things as they were understood, as they are understood, and most importantly, as they will ultimately be understood? Perhaps like Paul, we see now through a mirror darkly.

Moses 4:32 says that God’s words are true, “even as I will.” Shouldn’t God simply say they are true, period? What is the force of that final phrase? Does it mean that God’s words are as true as he wants them to be? I think there are several ways to understand Moses, but that is the one that is plausible to me.

That’s all I really want to say along those lines. The point being, we have to wrestle with the nature of revelation, as recorded with scripture, as it comes to prophets, modern and ancient, and this isn’t something we’ve done very much.

The examples I chose were both in the Bible and LDS scripture. And so this issue is neither new nor particular to Mormonism. If we share this problem with our Judeo-Christian cousins, we can also draw from their solutions. And so here I focus on two different ideas that may help, one theological and one a bit more philosophical. I consider myself more of a historian than either a philosopher or theologian, so I enter into both of these with appropriate fear and trembling.

First, is the idea of accommodation, also sometimes called condescension. Accommodation is the general principle that “divine revelation is adjusted to the disparate intellectual and spiritual level of humanity at different times in history.”[16] Since, per Isaiah 55:8-9, God’s thoughts are higher than our thoughts, God must “condescend” or come down to our level, and accommodate human weakness and understanding in order to communicate effectively. He adopts and adapts his audience’s language and cultural assumptions to do so. John Calvin expressed the corollary, that “if God would speak his own language, no one would understand Him,”[17] and this refers both to content as well as actual tongue. Put otherwise, in its most expansive form,

Accommodation is God’s adoption… of the human audience’s finite and fallen perspective. Its underlying conceptual assumption is that in many cases God does not correct our mistaken human viewpoints but merely assumes them in order to communicate with us.[18]

Accommodation functions both as 1) a theological statement about the nature of revelation and inspired communication—that it must be adapted to the human recipient’s state of understanding and is therefore partial, incomplete, and mediated as well as 2) an interpretive strategy, used to understand and reconcile passages or theologies of scripture in conflict with each other inside the Bible or in conflict with extra-biblical knowledge.

Briefly, this principle found extensive usage among Christians such as John Chrysostom (c. 349-407), who was nicknamed “the Father of Accommodation,” because he used it so much, Augustine (354-430), Erasmus (1466-1536), John Calvin (1509-1564), Galileo (1564-1642), Isaac Newton (1642-1726), and John Wesley (1703-1791). It’s a laundry list of who’s who in Christianity, as well as Judaism: Maimonides (1135-1204), all the way back as far back as Philo (25 BCE-50 CE). And also people you might be more familiar with, like Jesus, Paul, and Ezekiel. It is found explicitly three times in the Talmud, “The Torah speaks according to human language.”[19] And Thomas Aquinas phrased it as “scripture speaks according to the notions of the people.”[20]

This applied both to concepts as well as commandments. So Ezekiel speaks generically of God giving the Israelites “laws which were not good,” (Ezekiel 20:25) and perhaps an example of this is Deuteronomy 24, which lays out divorce regulations, and as is known in the Gospels; they come to Jesus and they say, what do you think about divorce? And this is actually where the Gospels differ: two of them say no divorce at all, and Matthew says divorce is tolerated but only if it’s in the case of adultery. But if you look at Matthew 19:8, Jesus explicitly makes use of this accommodationist principle: “It was because you were so hard-hearted that Moses allowed you to divorce your wives.” In other words, what Jesus is saying is, even though it’s Torah, even though it’s from God’s mouth, that doesn’t mean it reflects an ideal, eternal, ultimate perspective. God had to adapt even his laws down to your hard hearts, and that’s why divorce is allowed. So Jews such as Maimonides and others understood “human language” broadly, that the divine Torah reflected not just the human tongue, but the Torah also reflected human cultural, scientific, and moral understandings, which God adopted in order to give them the Torah.

What is significant about accommodation is that it implies a kind of revelation that is not binary truth versus error, but progressive, building upon previous revelations successively to move humanity forward as capacity increases. There is a natural affinity between accommodation and LDS ideas such as “line upon line” from Nephi’s interpretation of Isaiah, and other familiar passages such as D&C 1:24 (“Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding”) and 2 Nephi 31:3 (“For the Lord God giveth light unto the understanding; for he speaketh unto men according to their language, unto their understanding.”)

Accommodation as such is very at home in Mormonism even though you never find it by that name. Many LDS authorities such as Joseph Smith and Brigham Young have expressed accommodationist ideas or made implicit use of it in interpreting scripture. Compare John Calvin’s accommodationist metaphor about God speaking to us as children with D&C 50:40 and Joseph Smith’s statement about how Jesus would speak.

“For who even of slight intelligence does not understand that, as nurses commonly do with infants, God is wont in measure to ‘lisp’ in speaking to us?… To do this he must descend far beneath his loftiness”[21]

“Ye are little children and ye cannot bear all things now; ye must grow in grace and in the knowledge of the truth.” (D&C 50:40)

“If [Jesus] comes to a little child, he will adapt himself to the language and capacity of a little child.”[22]

Brigham Young spoke of accommodation in terms of both communication from the divine to us, but also in terms of missionary work. Talking to some missionaries, he said,

you are under the necessity of condescending to their low estate, so far as communication is concerned, in order to exalt them. You have to use the words they use, and address them in a manner to meet their capacities, in order to give them the knowledge you have to bestow. If an angel should come into this congregation, or visit any individual in it, and use the language he uses in heaven, what would we be benefited? Not any, because we could not understand a word he said. When angels come to visit mortals, they have to condescend to and assume, more or less, the condition of mortals, they have to descend to our capacities in order to communicate with us.[23]

When we get to the Book of Mormon, we find this with Ammon and King Lamoni in this famous passage that every missionary knows (Alma 18:24-28): “Ammon began to speak unto [Lamoni] with boldness, and said unto him: Believest thou that there is a God?” And Lamoni answered, and said: I don’t get it. And so Ammon’s response is: What about the Great Spirit? And he says, Oh yeah, OK, OK. And Ammon says: OK, that’s God. And then Ammon goes on and teaches him the basics of the Gospel. But what he does not do is, he does not say, “OK, now I know you’ve got this idea of the ‘great spirit,’ and there’s all this wrong stuff attached to it, and we need to get rid of that because none of that is actually right.” Ammon uses the king’s words, he leaves the baggage there, in order to do what is essential. And the other stuff comes later. He doesn’t correct Lamoni, he doesn’t clear anything up. He just moves on.

To drive home the point of accommodation one other way, trying to speak to you in multiple ways: Emily Dickinson captures in poetry what I have tried to explain in prose, how accommodation works in scripture. I don’t think she had this in mind, but it fits.

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

Accommodation is a well-established aspect of revelation, both in scripture, in Jewish and Christian history, and among LDS authorities. It should temper simplistic notions of revelation, whether “direct” or otherwise, whether modern or ancient, as absolute, complete, accurate in every point, and consisting purely of divine unmediated knowledge, as if it were a page out of God’s divine encyclopedia. Accommodation means that we should not expect Genesis to reflect modern cosmology or current knowledge about physical origins and the nature of the universe. God took the Israelites’ beliefs and used it to teach them certain things. Their pressing questions that needed divine answers are not ours, but we tend to impose our pressing questions on Genesis, because we’re unaware of what theirs were. And this is something I go into in my book, at great length. We know that the Israelites’ cosmology was shared among their neighbors. That’s one way we’ve come to understand certain puzzling passages in the Hebrew Bible, by looking at Akkadian and Ugaritic and other things.

Accommodation is one theological idea for tempering absolutist presuppositions of revelation and scripture. It helps us understand, on the divine end of things, why revelation may not be as absolute, as factual or “truthful,” if you like, as we think it should be.

I think some philosophical bits about the nature of perception, models, and communication can help us on the human interpretive side. And I’m going to use a series of images and examples to illustrate what I mean by this. We’re going to look at tools, we’re going to look at language, and we’re going to look at maps.

And we’re going to start with C.S. Lewis.

The first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship from a corkscrew to a cathedral is to know what it is – what it was intended to do and how it is meant to be used.[24]

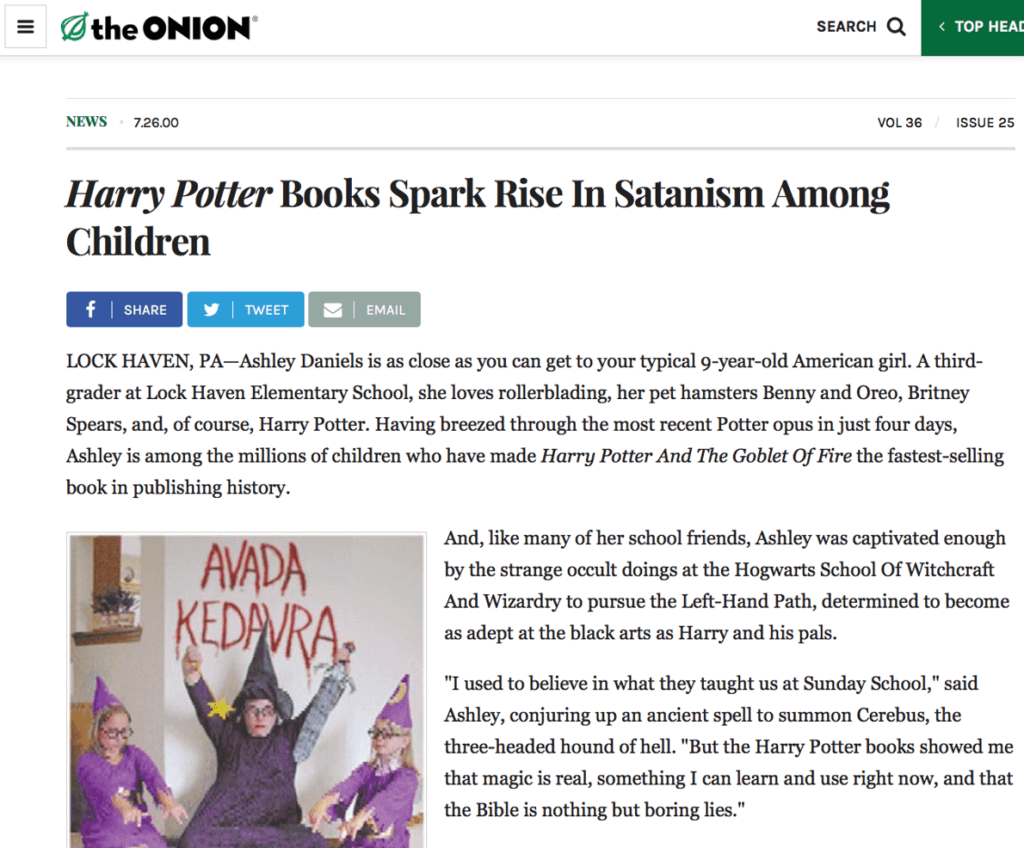

Human objects have a purpose, they are designed with intent. Sometimes we recognize that an object’s purpose is not obvious to us. Cook’s Illustrated regularly runs a column devoted to a picture of some older tool discovered in a barn or attic, and sent in by a reader trying to figure out just what the heck this is and what grandma did with it.

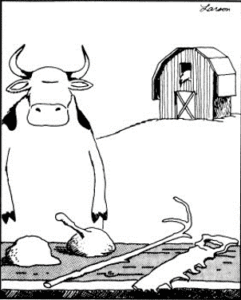

This is a jar opener, by the way. This kind of thing was exploited by Gary Larson in a famous panel that generated hundreds of letters to newspapers, trying to figure out what these “cow tools” did.

This is a jar opener, by the way. This kind of thing was exploited by Gary Larson in a famous panel that generated hundreds of letters to newspapers, trying to figure out what these “cow tools” did.

Larson’s response was “I have no idea; they’re cow tools.”[25] But in such cases, we know that we don’t know. We pick up one of these things, and we go, well, clearly this was used for something, but I have no idea what for; I can’t imagine.

Larson’s response was “I have no idea; they’re cow tools.”[25] But in such cases, we know that we don’t know. We pick up one of these things, and we go, well, clearly this was used for something, but I have no idea what for; I can’t imagine.

What happens when we think we know what something is for, a corkscrew for opening cans or a cathedral for entertaining tourists? If we misperceive purpose, we misuse and we misjudge the object.

I think this relates to scripture in two ways.

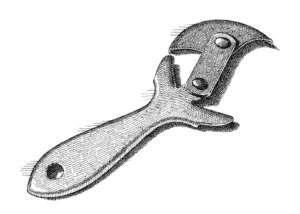

First, scripture includes a number of different types and genres: poetry, prose, parable, epistle, biography, legal text, ancient history, ancient historical fiction, narrative/epic, and so on. And if you’re interested in this, I have about a 45-minute podcast that just came out two weeks ago from LDS Perspectives, just on genre and the Old Testament. Just as misreading The Onion as actual news causes problems, so too does misreading genre. And this actually happened in the early 2000s, when Harry Potter was becoming popular and Evangelicals were very concerned about Harry Potter leading children into Satanism. And The Onion, which is a satirical magazine, maybe the original modern satirical magazine, ran this article and a lot of Evangelicals pointed to it as proof that Harry Potter was really leading children into Satanism.

They misunderstood the genre; they didn’t realize it was satire. As Walter Moberly says, “You cannot put good questions and expect fruitful answers from a text apart from a grasp of the kind of material it is in the first place; misjudge the genre, and you may skew many of the things you try to do with the text.”[26] On what basis do we legitimately expect that the genre of Genesis is meant as scientific recitation or historical narrative?

Second, and more generally, evaluating the truthfulness or reliability of a passage of scripture requires knowing what it was meant to do. That is, if your hammer is unsuccessful at screwing in a screw or measuring the length of your desk, should you discard the hammer as untrustworthy or unreliable? You might angrily throw it to the ground, but you’re also not using the hammer for what it was designed to do. If, for example, we approach scripture thinking that its purpose is to provide clear and consistent doctrinal propositions or ideal behavioral models to emulate, then when we encounter patriarchs acting badly in Genesis, we’re going to be really confused and frustrated. We may try to wrest scripture to make it say and do what we think it should. If we assume the purpose of the Genesis creation chapters was primarily to provide truths of a scientific and historical nature, we will badly misunderstand it. Our interpretation of scripture, our perception of its truthfulness or reliability, is skewed when we misperceive what it is trying to do. On what basis, again, do we assume that the primary purpose of Genesis was to explain physical origins?

Let me come at this from a different direction, using both language and maps.

Linguists sometimes talk about locution or what is said, and illocution or illocutionary force or what is intended and conveyed, what you actually mean. For example, at the dinner table, you may ask “Do we have any salt?” The locution is an inquiry about the possession of seasoning. And yet everyone here understands that if you responded “yes” and kept eating, you would have misunderstood. The illocutionary force of “do we have any salt” is “pass me the salt.” If scripture asks “do we have any salt” and our response is “yes,” then we are missing scripture’s illocutionary force.

Reading and judging scripture properly requires an accurate perception of what it is communicating, which means paying close attention to various kinds of context which the original hearers would have known. This means, in my view, that it is extremely difficult to understand what Genesis meant in a single English translation, without any kind of notes about how it was interacting with the ancient world. We are like someone in French 101, gone to France, who might understand the dictionary definition of words, but not how they all work together in particular French context.

To take a different example, if you’re in college and your roommate comes home and says, “you know, I just had a date with the hot girl in the other dorm.” And your roommate says, “Karen?” And he says, “yeah, Karen.” And you respond, “shut up!” “Get out!” You are neither asking him to stop talking nor to leave. And that is understood because of the context. There is nothing you can look up in the dictionary that will tell you that “shut up” sometimes means “please tell me the story” or that “get out” means “please have a seat and tell me the whole thing.” This is a contextual, idiomatic kind of thing. So when it comes to understanding the context of Genesis as the ancient Israelites might have understood it, we have to understand that, unlike the Book of Mormon which was written or edited for our day, most ancient scripture was written for its contemporaries. And so there was a lot that went “without being said” because they didn’t feel the need to include it; their contemporaries understood. Context went without being said.[27]

Rephrased with maps instead of languages, we have the famous idea expressed in the aphorism, “map is not territory.” That is, a map is a representation, a model of reality, but it does not and cannot correspond to reality perfectly. A map that perfectly corresponded to reality would simply be a physical copy. To properly read a map or model requires understanding which aspects pertain to reality and which aspects are incidental. For example, this is the London Tube map.

The London Tube map normally doesn’t move like a Harry Potter picture. What this is transitioning between is the Tube map as it appears, and the stations and routes of the Tube map mapped onto the actual geography. And so you can see that the Tube map distorts the actual geography of London. It corresponds to reality in the sense that it will accurately get you from stop to stop, but it is not accurate geographically or physically! You cannot navigate London streets with it. You can’t get around above ground with it. All maps and models distort, if only in their incompleteness. Now when we look at this, we recognize the genre of “Tube map” or “subway map”, and we compensate, we correct, we recognize the genre and we use it accordingly. We don’t try to go hiking with a map that doesn’t show elevations because we realize that for our purposes, we need a kind of map that corresponds the right way. Is the London map reliable, is it true? Yes, provided you understand what it’s meant to do, and how it functions. It is not reliable when you try to use it for something it wasn’t designed for.

To take another example, if I were to make a model of the solar system with a basketball as the sun, and planets as ping-pong balls, or ping-pong balls as planets, it would be misreading the model to say, “Ah, the sun is a large orange rubber thing created by the God Spalding.” You would be focusing in on those aspects of the model that were incidental and missing the ones that we’re trying to correspond with reality. And the farther we get into a culture that is not our own (like ancient Israelite Genesis), the easier it is to misread those models, those maps, because we don’t understand the conventions of them.

To take another example, if I were to make a model of the solar system with a basketball as the sun, and planets as ping-pong balls, or ping-pong balls as planets, it would be misreading the model to say, “Ah, the sun is a large orange rubber thing created by the God Spalding.” You would be focusing in on those aspects of the model that were incidental and missing the ones that we’re trying to correspond with reality. And the farther we get into a culture that is not our own (like ancient Israelite Genesis), the easier it is to misread those models, those maps, because we don’t understand the conventions of them.

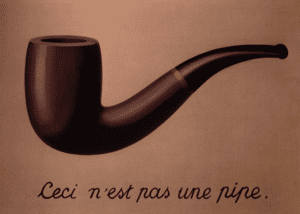

René Magritte played on this with his famous 1929 painting, The Treachery of Images “This is not a pipe.” It’s a painting of a pipe, it does not have the qualities of a pipe. Well, I suppose you could roll up the painting and smoke it, but it’s a picture of a pipe; it’s not a pipe itself. Map is not territory.

René Magritte played on this with his famous 1929 painting, The Treachery of Images “This is not a pipe.” It’s a painting of a pipe, it does not have the qualities of a pipe. Well, I suppose you could roll up the painting and smoke it, but it’s a picture of a pipe; it’s not a pipe itself. Map is not territory.

No map, model, or representation can accurately or fully capture reality, so it is imperative that we are able to properly distinguish at which points a given model is intended to correspond and how, that we distinguish how a map falls short or distorts the reality it is trying to represent. Look at this clip from the West Wing.

“Dr. John Fallow: The German cartographer, Mercator, originally designed this map in 1569 as a navigational tool for European sailors.

Professor Donald Huke: The map enlarges areas at the poles to create straight lines of constant bearing or geographic direction.

Cynthia Sayles: So, it makes it easier to cross an ocean.

Fallow: But…

C.J.: Yes?

Fallow: It distorts the relative size of nations and continents.

C.J.: Are you saying the map is wrong?”

“Are you saying the map is wrong?” And what they’re saying is, well, the map was designed to do certain things, and that means it distorts in these other ways. Well, is it wrong?

When I tell people what Genesis is really doing (which we do not have time for today; I have lectured about this; I T.A.’d a class last semester where I got to lecture about this, and we went three hours and covered two chalkboards), when I tell people what Genesis is really doing, briefly, they say, “you mean Genesis is wrong?” To which I reply, Genesis relates to reality in a way other than you expect with your modern presuppositions. It’s like the London tube map. Yes, it inherently has some distortion, but it works well for its purpose. But we moderns tend not to know what that purpose is, which is the whole point of my book. Our perception of how a given passage is meant to correspond to reality, its illocutionary force, its central truth is often obscured by lack of context, cultural change, reading in translation, and so on, and therefore we misunderstand it and we misjudge it. In my view, both young-earth creationists and those who read scripture to be clearly against evolution are misreading the model, misjudging the purpose of Genesis. These are interpretive questions. Can we recognize what Genesis was for, that is, what kind of tool it was designed to be? Do we speak the language and idiom of Genesis and understand its context, not just the dictionary meaning of the words? Are we rightly perceiving how the model Genesis puts forth is intended to relate to reality or are we unwittingly worshipping the orange God Spalding?

To conclude.

We all carry around a worldview and a set of assumptions about the nature of revelation, prophets, and scripture, and we’re usually unaware of what those are. Interrogating our own assumptions about these things will lead to a more solid understanding of scripture. Accommodation is one example that affects all three, that is, revelation, prophets, and scripture, and I think I’ve demonstrated that it has a fairly firm basis. Because we don’t really have formal or informal structures or guidelines on methods of interpretation, Mormons tend to rely on our presuppositions for face-value interpretations.

Is scripture truthful? Yes, provided that 1) we are able to accurately perceive what truth is intended by it and 2) that we recognize that divine truth is accommodative and progressive, not absolute and static. When we look at Genesis through the lens of accommodation, we should not expect it to reflect modern cosmology, physics, or geology. When viewed through the lens of language, object, and maps, which are modern things that I’ve tried to use to illustrate, I hope that becomes even clearer.

So, in the words of the late 20th century philosopher/poet Axl Rose, “Where do we go? Where do we go now?” In some sense I have created a problem and not told you how to solve it, and that’s a limitation of the time I have today. And so, let me make some suggestions:

First, there is a lot of very good non-LDS scholarship, Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish, on these topics. I have asked FairMormon to stock a couple of books that are out there: John Walton, Kenton Sparks,[28] Peter Enns, they are sold outside. If you wait about 15 minutes, I will have a post up on my blog, and you just google Benjamin the Scribe, that has a list of books and resources that you can go to for more on this. (Book post 1, book post 2)

More basically, get yourself a study Bible.[29] Study Bibles are modern translations with extensive notes and introductions to each book. If you’re uncomfortable with that, I would point out that General Authorities cite non-King James translations in General Conference.[30] When I taught New Testament at BYU, I was allowed to require students to read out of a second translation. And this will be on the blog, but I have an article from Religious Educator which comes out of BYU and goes to Seminary and Institute people, called “Why Bible Translations Differ” and at the back of that I have suggestions for personal study that talk about different study Bibles.[31] And they published that without any issues.

So look for good non-LDS scholarship. There is some good LDS scholarship, which I assume you are more familiar with. Get a study Bible. And check out my blog Benjamin the Scribe. Thank you.

Questions & Answers

(First Q&A card)… I’ve studied Arabic, but I don’t always do well with cursive.

Question: Who Wrote the Bible? by Richard Friedman?

Answer: This is a good book about the first five books of the Hebrew Bible that complicates ideas of authorship. The theory that he does … the way he presents it is a bit outdated, but it’s a very useful introduction. (It’s something I talk about in my book. David Bokovoy covers it in his book on the Old Testament, I can’t remember the title.) But that is a good book .

Q: Translation of the word in Genesis for “day”—does it mean a day? Does it mean a time period?

A: I spend a good bit of time on this in my book and so maybe I’m being unwise here, because it usually requires unpacking. In my book I argue fairly strongly that regarding “day” in Genesis 1, they are all 24-hour days, they are all literal days, but that does not mean that they are real days. If that’s confusing, let me put it this way: The Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland is a literal cat. That does not mean that it is a real cat, a historical cat. We know very clearly why the author of Genesis 1 put Genesis into a seven-day structure and it was not about dating the origins of the earth. I simply don’t have time to get into that too much. But I think it’s pretty clear that “day” is 24 hours.[32]

Q: How do we allow for accommodation when teaching or participating in Sunday lessons without becoming heretical?

A: Calling a spade a spade there, I guess. (Laughter) Accommodation is very much … so as I said, it’s two things: it’s both a principle about the nature of revelation, but it’s also a method of interpretation, and some of the examples I used, like Maimonides, they were actually trying to say, well, the Hebrew Bible clearly has God who is anthropomorphic, that is, human. How do we deal with that? And they said, well, accommodation. He had to appear to them like a human because that’s what they expected. Obviously, given our understanding of the nature of God, we would disagree with that application of it. And so it’s the application of accommodation that is always going to be tricky; it’s not a clear thing. In the medieval period, with Galileo, when Galileo was dealing with … was proposing heliocentrism and the Catholic Church scientists came back and said, “well, that’s contrary to what scripture says, that’s wrong,” we sometimes lose sight of the fact that the Catholic priests were right. Heliocentrism is contrary to scripture. And so Galileo and others kind of had to say, well, if this is wrong, and the science pretty clearly shows it is, and I don’t think anyone in here would dispute heliocentrism, I hope, then how do we make sense of the fact that the Bible doesn’t know that? And so he invoked accommodation to say, well, the Israelites wouldn’t have known that. We’ve just barely figured this out ourselves. Why would God tell them that? What purpose would it serve? So using it in Sunday School, I think you would have to have a lot of social capital. I think you would have to be very careful. And I think you would either have to be bold or stupid. It very much depends upon your local leadership.

Q: Do you believe that accommodation could at least in part explain the church’s changing politics in the past on race and priesthood?

A: Actually, I gave a paper at another conference yesterday at BYU, where I kind of addressed that directly, and accommodation was built into my answer, but I didn’t get into it nearly as much as today. I think the fact that culture is built into all prophetic statements and all scripture is not a bug, but a feature. That is, God is aware of it, God builds on it, and as revelation keeps coming, we progress and we iteratively grow closer to the ideal. That means that there is change, and sometimes uncomfortable change. And that does mean that the cultural standpoint of the prophet in some way affects the message that comes through him. That paper will be posted on the Maxwell Institute website within a couple of weeks. It’s part of the Summer Seminar.

Q: What parts of Joseph Smith’s black box of biblical interpretation should we consider valid, and are the lines drawn inescapably arbitrary?

A: I would say they aren’t arbitrary. The lines that we draw today are kind of based on our cultural understanding, and ditto Joseph Smith. A lot of the ways that he interpreted … Actually, let me go back a bit. When Jesus interprets scripture in the New Testament, his method of interpretation is virtually identical to the method of interpretation we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls and in the rabbis. Jesus interpreted scripture like a Second Century Jew. Paul interpreted scripture like a Second Century Jew. Neither of them, in that sense at least, transcended their culture in their public teaching, as recorded. I should caveat that way. If that’s the case even for the Son of God, (and I get into this in my book, whether he was deliberately doing this or whether this was part of his condescension in becoming human, it’s clear that Jesus taught and spoke like a Second Century Jew), if that applies even to the Son of God, then we shouldn’t expect it to not apply to Joseph Smith, a modern prophet, who also interpreted or approached scripture more or less like other people in the Nineteenth Century, in terms of method. That means that in some ways we do have to wrestle with his words. Let me relate this to something … well, if you’re in a hole, stop digging … because not everyone accepts the example I was about to use. I think what the church is doing right now, the church has arrived at a mature place where we can look at our tradition and we can see how much of our tradition actually comes through revelation and how much of it was more of a cultural influence. And I think we’re seeing that in the Gospel Topics Essays, and I think we will continue to see that as the church takes a critical look at the tradition we’ve inherited, because not everything that we’ve inherited is out of revelation. I think the Gospel Topics Essay on the priesthood and temple ban is the clearest example of that, where it contextualizes Brigham Young in terms of Nineteenth Century understandings of race, scripture, and the curse of Cain, which was an idea that Mormons inherited from their environment, and didn’t look at critically. It was baptized secretly and nobody knew. And that’s kind of the topic of the paper I gave yesterday.

Thank you.

[1] E.g. Bowler, Evolution: the History of an Idea (University of California Press, 2009)

[2] Young-earth creationism draws heavily on a particular reading of Genesis to argue that the earth is less than twenty-thousand years old, thus ruling out any evolution of humans or animals.

[3] Undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago, MA/PhD from Harvard https://truett.edu/directory/kurt-wise/

[4] The “deficit model” assumes that people reject evolution because they lack knowledge about it. For a popular overview, see http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2017/04/explaining_science_won_t_fix_information_illiteracy.html

[5] See http://creation.com/kurt-p-wise-geology-in-six-days

[6] Hugh B. Brown, quoting Anthony W. Ivins, “What Is Man and What May He Become?” in The Instructor, June 1958, p. 174.

[7] See e.g. the historical essays in The Search for Harmony: Essays on Science and Mormonism.

[8] See my post here.

[9] By this, I refer generically to anyone who receives revelation, not limited to those sustained as Prophets, Seers, and Revelators.

[10] John H. Walton, The NIV Application Commentary: Genesis, (Zondervan, 2001): 318.

[11] Smith outlived fellow apostles who had scientific training, after which he published his young-earth creationist Man, His Origin and Destiny (1954). After the deaths of Talmage, Widtsoe, etc., while internal debate continued, argument from those with scientific training would come to Smith from outside the quorum.

[12] In a Mormon context, see the Book of Mormon Critical Text project. For an introduction to Biblical text criticism, see e.g. Wegner, A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods, and Results (IVP, 2006)

[13] See my 2017 Sperry Symposium paper, “Reading the Old Testament in Context,” to be posted on my blog, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/benjaminthescribe/

[14] Joseph Smith manual, chapter 45, citing History of the Church, 6:366; from a discourse given by Joseph Smith on May 12, 1844, in Nauvoo, Illinois; reported by Thomas Bullock.)

[15] See my “Why Bible Translations Differ: A Guide for the Perplexed” Religious Educator, 15:1 (2004)

[16] Benin, The Footprints of God: Divine Accommodation in Jewish and Christian Thoughts, xiv.

[17] John Calvin, Serm. Gen. 1:20-25 (SupCal 11.1:101).

[18] Kenton Sparks, God’s Word in Human Words, 230-31.

[19] Berakhot 31b, Ketubot 67b, Yebamot 71a.

[20] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I-II q.98 a.3.

[21] Institutes, Book 1, Chapter 13, Section 1

[22] Ehat &Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 12.

[23] Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses 2:314.

[24] C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost.

[25] See the background in Larson’s, The PreHistory of the Far Side: A 10th Anniversary Exhibit.

[26] Walter Moberly, “How Should One Read the Early Chapters of Genesis” in Reading Genesis after Darwin (Oxford Press, 2009), 5.

[27] This idea is explored in depth in Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible (IVP, 2012).

[28] Particularly, God’s Word in Human Words, and Sacred Word, Broken Word.

[29] I recommend the Jewish Study Bible, Harper-Collins Study Bible, or NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible. The latter has excellent notes, but the NIV translation itself is highly biased and should be ignored.

[30] See examples in my “Why Bible Translations Differ” article, below.

[31] https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/re-15-no-1-2014/why-bible-translations-differ-guide-perplexed

[32] For more on interpretations of day and early Mormon attempts to reconcile Genesis with science, see the rough text of my Mormon History Association Paper, posted here.