Audio and Video Copyright © 2017 The Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research, Inc. Any reproduction or transcription of this material without prior express written permission is prohibited.

August 2017

A Tale of Two Jerusalems, Part 1: The Amarna Letters, 14th century BC

In 1887, a cache of cuneiform tablets dated to the mid-14th century BC was discovered in Amarna, Egypt. The collection primarily consisted of letters written by Canaanite rulers petitioning the Pharaoh to aide them in their petty squabbles with neighboring cities, including six letters written by the King of Jerusalem.[1] Based on these letters, Jerusalem at the time was a powerful regional capital, ruling over a “land” or even multiple “lands,” controlling subsidiary towns, and was even powerful enough to seize possession of the towns belonging to rival cities.[2]

There is just one problem: there is no archaeological evidence for this Jerusalem. According to Margreet Steiner, “No trace has ever been found of any city that could have been the [Jerusalem] of the Amarna letters.”[3] And yet, the letters are unquestionably authentic, and there is no doubt they mention Jerusalem.

Putting Away Childish Things

From this example, it is clear that genuine historical documents are not always supported by the archaeological record. This exposes the weakness of arguments predicated on the idea that if there is no archaeological evidence for something mentioned in the Book of Mormon, then the book must be false. Such arguments rest on what I would consider a misunderstanding of both archaeology and written history, and how the two relate to each other. Such misunderstandings come naturally, based on intuitive assumptions, but can be overcome by developing what historian and psychologist Sam Wineburg calls mature historical understanding.

The apostle Paul said, “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things” (1 Corinthians 13:12, emphasis added). All of us have experienced the need to “put away childish things” in our lives as we learn, grow, and expand our horizons. How we think, understand, and talk about scripture and how it relates to history and archaeology, is no exception to this.

Mature Historical Understanding

According to Wineburg, mature historical thinking “is neither a natural process nor something that springs automatically from psychological development.” Instead, it “actually goes against the grain of how we ordinarily think.”[4]

Writing in the late 1990s, Wineburg felt, “The odds of achieving mature historical understanding are stacked against us in a world in which Disney and MTV call the shots.”[5] Today, the world of Disney and MTV has given way to the world of Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, and Reddit—platforms which foster shallow thinking and make mature historical thought that much more of an uphill battle.

In conducting several case studies with students and teachers at all levels, Wineburg found that when confronted with difficult, strange, or challenging information about the past, people have a tendency to either take it at “face value” or seek to explain it by “borrow[ing] a context from their contemporary social world.”[6] Both of these approaches contextualize the past by importing the present—a fallacy known as presentism.

Properly contextualizing documents and events from the past is a major part of mature historical thinking, but it is not easy. Contexts are not self-existent—they must be fashioned from raw materials.[7] Wineburg explains, “Contexts are neither ‘found’ nor ‘located,’ and words are not ‘put’ into context. Context, from the Latin contexre, means to weave together, to engage in an active process of connecting things in a pattern.”[8] This is done by piecing together fragments of information from historical sources. When dealing with ancient history and archaeology, it involves an artifact here, a ruin there, and literally hundreds of tiny fragments of pottery—none of which are self-explanatory.

These pieces must then be brought together with the written sources—which are themselves incomplete and subjective representations of the past. As Jewish biblical scholar Oded Lipschits explained:

Reconstructing the history of Israel is a complicated process. Evidence from the Hebrew Bible, from archaeology, and from extrabiblical sources must first be interpreted independently of each other, and only then brought together and reinterpreted, in order to create a more complete and better-grounded picture.[9]

Similarly, a pair of Mayan scholars noted:

History is as much a construction of those writing it as the events it proposes to record, and this is as true of the Maya as of any other civilization. … Given that the public histories the Maya left behind them are not necessarily the truth, we must use archaeology to provide complementary information of all sorts—some confirming the written record, some qualifying it. It is upon the pattern of conjunction and disjunction between these two records that we base our interpretations of history.[10]

In some ways, this process is like putting together a large and complicated puzzle, where you must first understand the individual pieces and then figure out how they fit together within the larger picture. Except when it comes to historical context, you don’t have the complete picture on the box, you are missing most of the pieces, and the pieces you do have are often damaged and don’t usually fit perfectly together.

A Tale of Two Jerusalems, Part 2: 1 Nephi, 7th century BC

When dealing with the Book of Mormon, the same process must be followed—a context for it must be fashioned by bringing together archaeological, historical, and other ancient sources to create a “better-grounded picture” of Book of Mormon history, and all of this must be done with the limitations of our sources firmly in mind.

With that said, I would now like to take us back to Jerusalem, but we are going to fast forward to the 7th century BC. This is the Jerusalem where Lehi grew up and raised his family. Nephi’s account in the Book of Mormon provides a series of direct and indirect clues about Jerusalem during this time, and there is a rich array of archaeological data from this period that allows us to test this process and see how we might create a “better grounded picture” of Lehi and his family’s life and social setting.

As Nephi describes it, Jerusalem was a “great city,” surrounded by walls, and many—including his brothers—believed it could never be destroyed.[11] Lehi and Laban were descendants of the northern tribes that had lived their entire lives in Jerusalem,[12] and were wealthy and powerful members of the city’s social elite. Laban was among the ranks of government or military officials,[13] brandishing a sword of “most precious steel,” and maintaining an archive at his house of both family and official records, kept on metal plates and written with Egyptian.[14]

Meanwhile, Lehi’s family were wealthy Jerusalem residents with some unexpected skill sets. First, we know they can write,[15] an easy skill to overlook today, but usually a specialized skill in the ancient world. Second, they appear have metallurgical knowledge and expertise—also a specialized skill, known only to those who worked metals professionally.[16] But metalworking in antiquity is often seen as lower-class, “blue collar” work,[17] and you typically wouldn’t expect a metalsmith to also know how to read and write, nor a scribe to be able make tools of ore.

This is obviously only a brief summary, but there is enough here now to stop and ask: can a context be fashioned out of the raw materials of archaeology—and its interpretation by professional scholars—for this description of Jerusalem? As a matter of fact, yes—even for the more surprising details.

Margreet Steiner explained that based on current archaeology, by the 7th century BC, “Jerusalem had become what geographers call a primate city, a city very much larger than other settlements, where all economic, political and social power is centralized.” What’s more, it was “fortified by 5–7 m. wide city walls, which had been built at the end of the eighth century [BC].”[18] Jerusalem had, indeed, become “a great city,” and its walls no doubt provided a sense of security from external threats.

Archaeology further indicates that this transformation into “one of the major cities in the known world” was precipitated by “a huge influx of refugees from the north[ern kingdom] into Jerusalem.”[19] An extension of the city was created to accommodate these refugees, and a recent archaeological excavation in that area revealed “an impressively large” Israelite home, with several stamp seals,[20] leading to the conclusion that “members of Judah’s social elite,” and possibly even “of the ruling class in Judah’s capital,”[21] lived there around the 7th century BC. Thus, descendants of northern Israelites were indeed living in the city, and were part of the upper class.

In another dig among 7th century BC homes “belonging to what may be called the elite of Jerusalem,” archaeologists found “a bronze workshop” including “pieces of bronze and iron” along with evidence of imported luxury goods in the home.[22] Evidence from mines out in the desert near the Red Sea likewise confirm that in the early-1st millennium BC, rather than “armies of slaves engaged in back-breaking labour … specialist metalworkers are often accorded high social status.”[23]

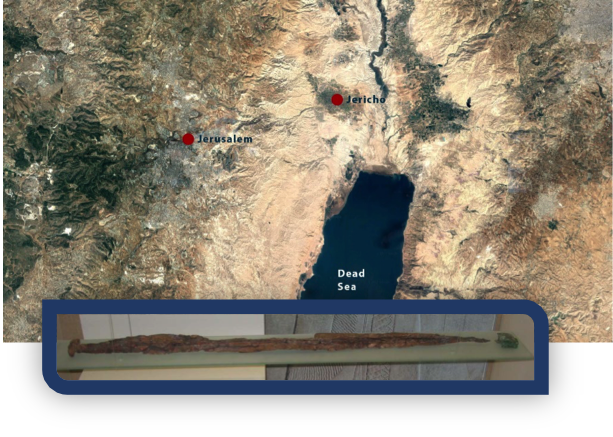

Skilled metalworkers at the time were working both copper and iron, and whether deliberately or not, carburizing iron into steel.[24] Metallurgical analysis of a meter-long sword found near Jericho (about 15 miles from Jerusalem) and dated to the end of the 7th century BC indicated “that the iron was deliberately hardened into steel,” making it comparable to Laban’s sword.[25]

Archaeology also indicates an increasing number of inscriptions and texts at this time, leading many scholars to conclude that literacy was on the rise.[26] Recent scientific analysis on writing samples from a military outpost in Judah concluded “a significant number of literate individuals can be assumed to have lived in Judah ca. 600 BCE,” and that literary awareness was had “by the lowest echelons of society.”[27] While the actual extent of literacy remains a hotly debated subject among scholars, many do agree that at least some high-status craftsmen in Jerusalem at this time could read and write.[28] Craftsmen who worked with materials that could be used as a writing medium—such as stonemasons, potters, and metalworkers—were particularly likely to develop some scribal skills.[29] In fact, some of the earliest evidence for alphabetic writing in the region of Judah comes from journeymen metalsmiths, and “tangibly connects the crafts of scribe and metalworker.”[30]

While excavating 7th century BC homes likely belonging to wealthy artisans and traders, a single home yielded 51 clay impressions of stamp seals used to seal documents, which Steiner interpreted as “the remains of an archive.” Some archaeologists have interpreted it as a “state archive,” but its domestic contexts suggest to others that it was a “private archive.”[31] In addition, letters found at the nearby city of Lachish dating to the early 6th century BC attest to the practice of keeping records in the homes of military officials.[32] Both of these finds should remind us of Laban and his “treasury.”

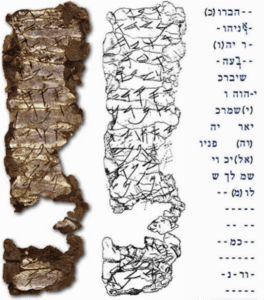

Of course, these records were not kept on metal,[33] but many other records from the ancient Near East were—including the oldest surviving example of a biblical text.[34] Two small silver scrolls, dated to the 6th–7th century BC, were found just outside of Jerusalem, with a version of Numbers 6:24–26 inscribed on them.[35] These short texts are of a very different nature than the brass plates, but do nonetheless demonstrate that metallic epigraphy was practiced in Jerusalem in Lehi’s day.[36]

Egyptian writing is also attested.[37] Over 200 texts utilizing Egyptian hieratic have been found in the regions of Israel and Judah, including several found right in Jerusalem, and many of these are dated to 7th–6th centuries BC.[38] Most of these are short, fragmentary texts where hieratic numerals and measurements are mixed with Hebrew, but after carefully reviewing samples from the late 7th century BC, David Calabro concluded that “the hieratic tradition in Judah lasted in fuller form than only the isolated use of numbers and units of measurement.” Calabro felt that the evidence “indicates a widespread presence of scribes educated in this Judahite variety of Egyptian script.”[39]

Of course, the picture is not perfect, and skeptics will no doubt find the holes and seek to exploit them—but don’t forget what we learned from the Amarna letters: archaeology does not always back up every detail found in historical documents. Whatever pieces might still be missing, there is really no question that Nephi’s Jerusalem fares a whole lot better than Amarna’s, and no one questions the authenticity of those letters. The point is that once the pieces are put together, Nephi’s Jerusalem is surprisingly believable—but we have to be willing to take the time to find the pieces, sort them out, and put them in place to see that (see table 1).

| Table 1: Text and Context for Nephi’s Jerusalem | |

| Book of Mormon | Archaeology |

| “Great city,” with walls, supposedly indestructible | Has become a “primate city,” fortified by large walls |

| Lehi and Laban are descendants of Joseph through Manasseh | Growth due to northern Israelite refugees, ca. 722 BC |

| Both Lehi and Laban are wealthy, and Laban is a powerful Jerusalem official | Descendants of northern refugees are part of Jerusalem’s elites, including government officials |

| Lehi and Nephi can read, write, and work with metals | Metalworkers are among the social elite, and literacy is spreading to non-scribal elites, including craftsmen like metalworkers |

| Official and family records repository kept in Laban’s home | Private archives in the homes of wealthy individuals, and state archives being kept in the homes of military officers |

| Records kept on metal (brass) plates, written in Egyptian. | Writing on metal (silver) scrolls, and 200 samples of Egyptian hieratic writing found throughout the region |

| Laban has a sword made of steel | Steel sword found at Jericho |

Benefits of Mature Historical Understanding

It is my belief that although learning to read the Book of Mormon this way is difficult and takes time, it is worth the effort. I’ve personally found that when I approach the Book of Mormon with mature historical understanding and thought, it:

- Builds Faith

- Accommodates Questions

- Deepens Understanding

Drawing on the work I and others have done over the last 2 years at Book of Mormon Central, I would like to offer just a few examples of what I mean.

1. Builds Faith

When the context from archaeology and the details in the Book of Mormon converge, to use William Dever’s term,[40] it can build faith and confidence that the Book of Mormon is a genuine historical record.

Jerusalem

I’ve actually already provided one example of this by talking about Jerusalem. We don’t usually think about the mention of Jerusalem as “evidence” or something that can be faith building, because its mentioned in the Bible, so it seems like that would be a “given” for Joseph to get right. But as any ancient Near Eastern archaeologist can tell you, things mentioned in the Bible are hardly archaeological “givens.”[41] We’ve already seen that Nephi’s Jerusalem fares better than Amarna’s, but you could argue it does better than David’s and Solomon’s too.[42]

If Joseph Smith’s wife is to be trusted, he didn’t even know Jerusalem had walls around it in Lehi’s day,[43] so the overall accurate picture of Jerusalem ought to count for something—especially since several of the details were once ridiculed by Joseph’s critics.[44] That Laban, Lehi, and the rest of his family can be so well contextualized can build faith that the story is being told by someone who was actually there, in Jerusalem, ca. 600 BC.

Nahom

By now, all or most of you have probably already heard about Nahom, often touted as “the first actual archaeological evidence for the historicity of the Book of Mormon.”[45] Nahom was the place where Lehi’s family buried Ishmael and then turned course “nearly eastward” until arriving in a rich and fertile land they called “Bountiful” (1 Nephi 16:34–17:5). The first indication that we might actually be able to locate Nahom on a map came in the late 1970s, when Ross T. Christensen noticed the mention of Nehhm in Yemen, “about 25 miles north of the capital, Sana” on an old, 18th century German map of Arabia. Located “only a little south of the route” then recently drawn by Lynn and Hope Hilton, Nehhm was in the right general area, but it was uncertain whether it was there in Lehi’s day.[46]

Further research revealed that Nehem, also spelled Naham, Nihm, and various other ways, was the land of the Nihm tribe, which had been there at least since early Islamic times.[47] Then in the late-1990s, S. Kent Brown noticed an altar from a temple site at Mārʾib, dated to the 6th–7th centuries BC, recording the dedication of one Biʾathtar, whose grandfather was a Nihmite.[48] Two other identical inscriptions were subsequently found,[49] and all three were later dated to a slightly earlier time period, close to 685 BC, placing its writing in a phase of construction around the 8th–7th centuries BC.[50]

While this was the first archaeological evidence noticed by LDS scholars, subsequent research has revealed that several other first millennium BC inscriptions mentioning Nihmites in the area west of Mārʾib were already known to scholars of south Arabia.[51] These inscriptions have led scholars to the conclusion that Nihm was in the same general area since BC times.[52]

Hence Alexander Sima said that Biʾathtar the Nihmite “comes from the Nihm region, west of Mārib.”[53] Burkhard Vogt noted that the Nihm tribe was “at the time without doubt north of Jawf, today northeast of Sanʾa.”[54] Peter Stein included NHM on a map providing an “overview of places … as well as other identifiable toponyms” found in a collection of Sabean texts from later BC to early AD times, and identifies it with the modern Nihm region.[55] Thus, scholars consistently locate the place of the Nihm tribe in approximately the same location going back to the 1st millennium BC.[56]

What’s more, is it in the vicinity of Nihm that eastward travel becomes possible,[57] and nearly due east of Nihm is an inlet along the coast which meets all the criteria for Bountiful.[58] When all the pieces are brought together—the name, the location, the antiquity attested in several inscriptions, the “bountiful” inlet and the turn eastward—it creates a compelling context for this portion of Nephi’s account in southern Arabia, which in turn can build faith that the Book of Mormon is an authentic historical document.[59]

Mulek

The next most direct evidence for the Book of Mormon comes from an artifact which may have belonged to Mulek, the son of Zedekiah who, according to the Book of Mormon, escaped the fate of his brothers and made his way with a small group to the Americas.[60] Long thought to be uniquely attested to in the Book of Mormon, it turns out there may be a reference to Mulek in the Bible. During the final years of Zedekiah’s reign, shortly before the Babylonians finally conquered Jerusalem (ca. 588–586 BC), Jeremiah was imprisoned in “the dungeon of Malchiah the son of Hammelech” as it says in the King James Bible (Jeremiah 38:6). More recent translations correct this to “Malchiah, the king’s son” (e.g., NRSV, JSB, NIV).[61] Given the context, this Malchiah (also spelled Malkijah, Malkiah, and Milkiah),[62] or Malkiyahu in Hebrew, was likely “a contemporary son of king Zedekiah,” according to Yohanan Aharoni.[63]

In the 1990s, a stamp seal paleographically dated to “the second half of the seventh or early sixth century [BC],”[64] turned up bearing the inscription “Belonging to Malkiyahu son of the king.”[65] Since the information about Malkiyahu in both the Bible and this inscription is quite limited, an absolute identification remains uncertain, but Lawrence Mykytiuk considered this connection as among those “reasonable enough to invite assumption.”[66] If this is indeed the same Malchiah as that mentioned in Jeremiah, this find may not only be another identification of a biblical person, but it might be the first known artifact belonging to a Book of Mormon person as well.

Both Mulek and Malchiah are based on the same Hebrew root (mlk, “king”), and Mulek may be a short form of Malchiah, just as Mike is to Michael today.[67] Learning of this possibility from LDS colleagues, David Noel Freedman thought, “If Joseph Smith came up with that one, he did pretty good!”[68] Taken together, both the biblical reference and the stamp seal add context to who Mulek was that can build faith in his reality as a real, historical member of the royal family in Lehi’s time.[69]

Cement

This next example is less direct, but more concrete.[70] Mormon described extensive cement working beginning around 50/49 BC,[71] in a place far to the north of the Nephite homeland. The people there built cement homes and even whole cities made from wood and cement, despite the fact that the region suffered from severe deforestation and they had to supplement their small natural timber supply by having lumber shipped from other regions (Helaman 3:3–11).

Notwithstanding early 19th century reports of Peruvian cement from Alexander von Humboldt,[72] currently the only pre-Columbian cement found by archaeologists is in Mesoamerica.[73] In 1839, John Lloyd Stephens observed cement at several of the Maya cities,[74] but little was known about its use, composition, antiquity, and development until the latter half of the 20th century. Now, Mesoamerican use of limestone-based cement from very ancient times is well documented.[75]

Non-structural lime plasters and stuccos were used as early as 1100–600 BC,[76] and “through the Late Preclassic period [ca. 300 BC–AD 250] … the thickness and quality of plasters increased,” and Maya builders made “improvement[s] in mixing techniques.”[77] According to Michael Coe and Stephen Houston, during this time-period the lowland Maya “quickly realized the structural value of a concrete-like fill made from limestone rubble and marl,” contributing to “an explosion of [building] activity around 100 BC” in the Northern Petén.[78]

In the Valley of Mexico, fully developed cement appeared at Teotihuacán from seemingly out of nowhere in the 1st century AD.[79] By the early Classic period (ca. AD 300–600), cement use had declined in the Maya area,[80] but not at Teotihuacán. There, by AD 300, “most inhabitants lived in substantial plaster-and-concrete compounds composed of multiple apartments.”[81] The city is well known for its obsidian industries, but according to John Clark, “these pale beside its cement consumption.”[82]

“Concrete,” says Carlos Margain, “is encountered in all Teotihuacan constructions of every epoch.”[83] It has also been noted by Nigel Davis that, “excessive use of timber in Teotihuacan denuded the hillsides and led to soil erosion.”[84] Large quantities of wood were needed in the production of cement,[85] and wooden beams were used to support roofs, as well as being in the center of columns, pillars, and door lintels.[86] Indeed, Teotihuacán and other cities in the region were certainly cities made of wood and cement.[87]

Overall, Mormon’s report in Helaman 3:3–11 turns out to be a highly realistic account in the context of structural cement spreading through Mesoamerica in the 1st centuries BC/AD, with cities emerging in Northern Mesoamerica made extensively from wood and cement in a region largely deforested by Mormon’s day.[88] This realistic setting can build faith that the Book of Mormon provides authentic information about pre-Columbian America, just as Joseph Smith claimed it did.[89]

2. Accommodates Questions

Sitting with Discomfort

It is important to keep in mind, however, that this process is not about proving the Book of Mormon, or any other historical work, is true. Rather, as quoted earlier, it is about gaining a “better grounded picture,” a process that will sometimes confirm, but other times qualify what our written record says, or at least how we interpret it. To do this, we must be able to acknowledge that our current understanding is deficient—it is hard to improve our understanding when we think we’ve already got it all figured out. We are trying to mature our understanding, and to mature is to change, to develop, to grow—and growing comes with growing pains.

Sometimes information from the past is jarring. Wineburg warns that “mature historical cognition” does not just engage the mind, but is also “an act that engages the heart.”[90] This is all the more so with the Book of Mormon, when not only historical facts but our faith is often on the line. Persistent questions raised by apparent contradictions in the archaeological context can seem devastating.

Wineburg found that mature historical thinkers displayed patience with the unknown. They were able to call attention to apparent contradictions without immediately seeking to resolve them. This was often uncomfortable, but mature historical thinkers “sat with this discomfort” as they continued to review addition sources.[91] As they did this, they exercised what Wineburg called the “specification of ignorance”: a practice of identifying when you do not know enough to understand something.[92] This is then followed by “cultivating puzzlement”: being able “to stand back from first impressions, to question … quick leaps of mind, and to keep track of … questions that together pointed … in the direction of new learning.”[93]

When approached this way, “Inconsistencies become opportunities for exploring our discontinuity with the past.”[94] Or, as Hugh Nibley put it, “every paradox and anomaly is really a broad hint that new knowledge is awaiting us if we will only go after it.”[95]

When it comes to the Book of Mormon, some of the most persistent questions pertain to anachronistic plants, animals, and technology. But these anachronisms may be a product of how we read the Book of Mormon in the first place. Wineburg notes, “Trying to reconstruct a world we cannot completely know may be the difference between a contextualized and an anachronistic reading of the past.”[96]

Rather than letting questions drive us to anachronistic readings and immediate, premature dismissals, the patience of mature historical thought can allow us to use questions to create contexts which accommodate them and lead to greater learning.[97]

Barley and Archaeology

An important first step in this process goes back to the point I made at the beginning of this presentation: not everything mentioned in written sources gets verified by archaeology. Scholars of the ancient world value inscriptions and other written sources precisely because they can speak to us more directly than potshards and crumbled walls ever will. Requiring a written source to conform to what is presently known through archaeology thus strips it of the very thing that gives written sources their value in the first place.[98]

The problem is compounded by the fact that archaeology is a moving target. Archaeologists don’t just dig into the ground once and suddenly know everything about the past. Instead, archaeology is an ongoing process, and much work remains to be done. Just among the Maya, archaeologists estimate that only 1–5 percent of all sites have been excavated, leading the late-George Stuart to conclude: “we don’t know squat.”[99]

The implications of this should be obvious: with 95-plus percent of known Maya sites—to say nothing of the rest of Mesoamerica—unexcavated, there is no telling what may yet be found. All the archaeological data that I’ve already mentioned was, at some point, missing and unavailable, and thus contexts that can now be fashioned couldn’t have been created any earlier than the late-20th century.

In terms of what this means for anachronisms, consider barley.[100] Since at least 1887, barley has been frequently included on lists of anachronistic plants mentioned in the Book of Mormon.[101] In 1983, however, Daniel B. Adams reported that “salvage archaeologists found preserved grains of what looks like domesticated barley” at a Hohokam site near Phoenix, AZ, dated to AD 900.[102] The grain was an indigenous American species known as little barley, and although this was “the first ever found in the New World,”[103] cultivated specimens of little barley have since been identified at several pre-Columbian sites, mostly in the Eastern United States,[104] though “extensive archaeological evidence also points to the cultivation of little barley in the Southwest and parts of Mexico,”[105] and possibly even Cuba.[106]

Little barley’s exact cultivation and domestication history remains debated, but today scholars generally agree that it was among the major cultivated crops in the Eastern United States by 200 BC.[107] Some will protest that it is not “true” (Old World) barley,[108] but nothing in the Book of Mormon requires such a deliberately anachronistic reading.[109]

Discoveries like little barley are exactly why archaeologist John E. Clark warns, “negative items may prove to be positive ones in hiding. ‘Missing’ evidence focuses further research, but it lacks compelling logical force in arguments because it represents the absence of information rather than secure evidence.”[110] Clark documented that the long-term trend in archaeological data has been toward verification of Book of Mormon claims.[111] This long-term trend toward verification, along with the overall limitations of current archaeological knowledge, provides a context in which we can patiently accommodate questions about remaining anachronisms.[112]

When a Horse Isn’t a Horse

While awaiting further information from archaeology, there are other ways to accommodate unconfirmed details through contextual, rather than anachronistic, readings. For instance, there are numerous historic examples of explorers and settlers encountering new plant and animal species, just as Lehi and his family would have as they settled in the New World. Such encounters inevitably create linguistic problems. One of the most common solutions to this problem is called loanshifting, which, according to Lawrence B. Kiddle, means “to give the animal the name of a familiar animal which the receiving speakers believe it resembles.”[113] The most effective way I’ve found to illustrate loanshifting is through a simple question: which one of these animals is a buffalo?

In most (American) audiences, people usually point to the one of the right, but that is technically a bison. The “true” buffalo is on the left. Early French and English explorers and settlers had never seen a bison before, and thus lacked a proper term for it. So they borrowed—or loanshifted—the name of an animal already familiar to them: buffalo. Obviously, the name has stuck, despite the fact that scientists have ruled it taxonomically incorrect.[114] Other examples of loanshifting from European contact with the Americas include robin, which is the original name of an unrelated bird species common to most of Europe, and elk, which still means moose in most of the rest of the world today.[115]

Europeans coming to the New World were not the only ones who struggled to label new animal species. The introduction of Old World animals into the New World, such as horses and cattle, also created labeling problems for Native Americans and terms for widely different species—such as deer, tapirs, and most commonly dogs—were loanshifted to horses by various native cultures throughout the Americas (see table 2).[116]

| Table 2: Native American Loanwords for Horse | ||

| Original Meaning | Frequency | Geographic Region |

| Dog | 47/105 (~45%) | North America (ex. Mexico) |

| Deer | 19/105 (~18%) | North America |

| Elk | 8/105 (~8%) | North America (ex. Mexico) |

| Tapir | 8/105 (~8%) | Central & South America |

| Caribou | 4/105 (~4%) | North America (ex. Mexico) |

| Guanaco | 1/105 (~1%) | South America |

“Among these,” noted linguistic anthropologist Cecil Brown, “horse is most closely related to tapir, … so that this naming association is understandable in terms of the closest analogue model.”[117] Brown was surprised, however, by how frequently Native Americans used dog for horse.

From a commonsense perspective, one might expect that … Amerindians would typically have analyzed dog as being least similar to horse because of its relatively small size. Nonetheless, terms for dog are considerably more commonly extended to horse than are labels for other, more horselike-in-size creatures.[118]

From this, it is clear that the specific associations made in various loanshifts are not always “obvious” or what would appear to outsiders as the most logical.

Once loanshifts are made, they often stick for several generations, as evidenced by the fact that we are still using several ourselves (buffalo, elk, robin) from the early post-Columbian period 400–500 years ago, as are many Native Americans. In fact, many common names for animals, as well plants and even objects, are loanshifts made long ago and now widely accepted without any awareness of what they originally meant. For instance, hippopotamus is a Greek term meaning “horse of the river,” which came into use at least as early as the 5th century BC and continues to be used today,[119] despite the fact that hippos obviously aren’t horses.

Considering Lehi and his family arriving in the New World with this widely attested practice in mind, they could have applied their Old World terms for cow, ox, ass, horse, and goat to indigenous species found in the forests of the promised land (1 Nephi 18:24).[120] Although the idea is frequently mocked online, if Lehi and his family were real people, then we would expect them to act the way real people have historically acted in similar situations. Understanding this common practice thus creates a context that can accommodate questions about horses, as well as other Old World plant and animal names mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

Chariots and Translation

Another important thing to remember is that the Book of Mormon is a translation, and translations sometimes create anachronisms, or at least misconceptions, that were not there in the original text. The King James Bible, for example, frequently mentions candles and candlesticks, yet ancient Jews and Israelites did not use candles, but rather oil lamps, thus more contemporary translations properly use lamps and lampstands instead.[121]

Although not strictly an anachronism in the Biblical world, the use of chariot in the King James rendering of Song of Solomon 3:9 is another example where the translation may create a misunderstanding. The Hebrew word here is afiryon, which actually refers to a litter or palanquin, which is “an enclosed couch carried by bearers.”[122] This interesting bit of trivia may be relevant to references to chariots in the Book of Mormon.[123]

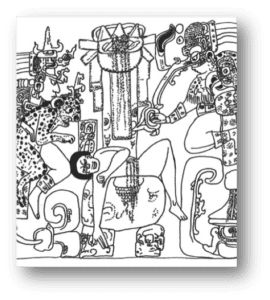

Although late-19th century French archaeologist Désiré Charnay actually reported finding “chariots” in Mexico, these were merely “toys,” or figurines.[124] No chariot-like wheeled vehicles have yet been found in pre-Columbian America, but litters or palanquins like that mentioned in the Song of Solomon were known and widely used for royal visits in Mesoamerica as early as the Late Preclassic period (ca. 300–50 BC).[125]

Although such a “chariot” would not be drawn by horses, it is important to notice that neither are the chariots in the Book of Mormon ever described as being pulled by horses, but rather are simply prepared with horses. In Maya art from the Classic period (ca. AD 300–900), at least, an animal (often a dog) is frequently depicted as traveling near the litter as part of the entourage,[126] thus indicating that both animal and royal litter would need to be made ready for a royal visit.[127]

The chariots of Lamoni are twice made ready for occasions not unlike those in which royal litters would be used to “conduct [the king] forth” (Alma 18:9) in Mesoamerica. Understanding the Book of Mormon in the context of translations, with the difficulties and imprecisions that all translations come with,[128] can thus accommodate the mention of chariots, but it creates a considerably different picture than what we are used to envisioning here.[129]

The Obvious and the Evidence

The mention of horses and chariots together brings the image of horse-drawn chariots so naturally to our minds, it seems obvious that this must be what the text is referring to—even if the horses are never said to be pulling the chariots explicitly. But, to paraphrase Lt. Megan Donner on an episode of CSI: Miami, “The problem with the obvious, … is it can make you overlook the evidence.”

Wineburg noticed this same tendency in some of his case studies. After reviewing primary source accounts describing the Battle of Lexington, for instance, students and historians were shown different artistic depictions of the event and asked to “select the picture that best reflected the written evidence.”[130] One student, who made very astute observations while reading the documents, nonetheless choose the image that most reflected “his own modern notions of battlefield propriety,” and justified that choice based on modern combat rationales, while dismissing the more accurate image as being “ludicrous.”[131] What was obvious and natural to this late-20th century student, however, was actually at odds with 18th century military decorum, yet even direct engagement with the evidence couldn’t overcome his deeply held assumptions about battlefield behavior.

My point here is that obviousness depends on context. The past sometimes is very strange, and what might seem ludicrous to us may very well be obvious to someone living in a different time and place. To us, the idea that horse and chariot might refer to anything besides a horse-drawn, wheeled vehicle might seem absurd, yet to a Nephite living in Mesoamerica in the first century BC, the use of their terms translated as horse and chariot might appear to be a rather obvious reference to a royal litter accompanied by a dog or another animal.[132]

This is a very different picture than what we are used to, and not everyone may be entirely comfortable with it. Yet, like I explained earlier, developing mature historical understanding will sometimes require us to “sit with our discomfort” as we learn to allow the context we fashion to change and expand our understanding.

Clarification and Caveat

To be clear, I am not saying that the horse and chariot of the Book of Mormon absolutely is a dog and royal litter. I am merely seeking to illustrate some of the different ways mature, contextual approaches can accommodate persisting questions about Book of Mormon claims. The principles discussed here can be applied to other currently “missing” plants, animals, and technologies while always keeping in mind the limited nature of archaeology and the possibility of future finds.

Speaking of the Bible, one pair of scholars remarked, “the trend of archaeological discovery is to confirm even points that opinion had rejected as false.”[133] As already discussed, there is a similar trend with the Book of Mormon.[134] Horses and chariots may yet conform to this trend. There is already some ambiguous evidence for pre-Columbian horses,[135] and the presence of wheeled figurines demonstrates, at the very least, that “the principle of using wheels to facilitate horizontal movement was familiar to at least some peoples of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.”[136] While patiently awaiting further discovery, however, it is valuable to consider other contextual approaches and grow more comfortable with different interpretive possibilities.

3. Deepen Understanding

I don’t recommend spending too much time dwelling on what we are missing, however: there is far too much already available from archaeology and other disciplines that not only builds faith, but also enriches and deepens our understanding of the Book of Mormon. Beyond waiting and weighing possible answers to difficult questions, I recommend diving into what we already know to see what new things there are to learn about the Book of Mormon and, consequently, the gospel principles it teaches.

Olives and Allegories

A basic example of this is Jacob 5. This chapter comprises of an extended allegory about olive cultivation, and is the longest chapter in all of the Book of Mormon—a curious little detail, since olives don’t grow in New York, but are ubiquitous to the ancient Near East and Mediterranean region.[137] As an allegory for the last days, it is imperative for us to understand it well, and one way to do that is to dig into botanical science and ancient horticultural practices, going back to the allegory’s ancient roots to gain greater context.

Scholars and scientists have done just that, and their efforts have yielded a rich harvest.[138] One of the more interesting insights comes in relation to grafting wild branches into a domesticated tree. In Jacob 5, after an initial effort to save the decaying tree fails, the master has wild branches grafted into it, seemingly as a last-ditch effort (vv. 7–10). Miraculously, the tree begins to bear fruit again (v. 17), and the servant observes, “because thou didst graft in the branches of the wild olive tree they have nourished the roots, that they are alive and they have not perished” (v. 34).

Botanist Wilford Hess, writing with other scholars, observed, “It would … have been unusual for an olive grower to graft wild branches onto a tame tree.”[139] Hess stressed that “olive growers normally use wild olive grafts only to rejuvenate domesticated or tame trees.”[140] In such circumstances, “Due to the vigor and disease resistance of certain wild species, grafting wild stock onto a tame tree can strengthen and revitalize a distressed plant.”[141]

This is, of course, exactly why the wild grafts are done in Jacob 5, and the results are precisely that of a rejuvenated tree, but what I would like to point out is that this is not something an olive grower would just do on an annual basis: it’s a last resort, a desperate move made when all else has failed. The message seems clear: the Lord will stop at nothing to reclaim to his lost fruit—and don’t forget that fruit is us.

This important context thus deepens our understanding of the great lengths Heavenly Father will go to in order to reclaim his lost children, even resorting to unconventional, desperate, and perhaps even counterintuitive methods, if he has too.[142]

Revelation in Context: From the Old World to the New

This year, to go along with the Gospel Doctrine curriculum, the Church published a manual called Revelations in Context, which includes essays discussing the historical background of the various sections of the Doctrine and Covenants.[143] Revelatory experiences in the Book of Mormon can also be contextualized, and doing so can deepen our appreciation for the doctrines revealed, but can also teach us something about the very nature of revelation itself.

Old World Patterns of Revelation

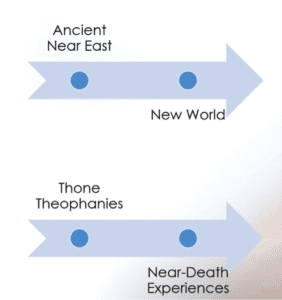

The very first vision in the Book of Mormon is that of Lehi’s, where he sees God on his throne surrounded by angelic hosts (1 Nephi 1:8–14). Several scholars have illustrated that the sequence of events here fits the prophetic call patterns found in biblical and non-biblical texts from the ancient Near East.[144] Nephi’s vision upon a “high mountain” is likewise consistent with ancient Near Eastern patterns (1 Nephi 11–14).[145] Thus, analysis of these revelations predictably benefits from contexts fashioned from the biblical world.[146]

Transitioning Revelation: An Old and New World Ritual Context

King Benjamin’s revelation from an angel, ca. 128/127 BC,[147] shared during a festival occasion where sacrifices mandated by Mosaic law were performed (Mosiah 2:3), naturally becomes more interesting in light of rituals associated with the Israelite festival occasions.[148] Specifically, the sprinkling of bull and goat blood 7 times to purify the sanctuary and the people from sin (Leviticus 16:14–19)[149] on the Day of Atonement creates a vivid context for the angel’s revelation that the “blood of Christ atoneth for … sins” (Mosiah 3:16)—with blood repeated 7 times in the course of Benjamin’s speech.[150]

There were festival occasions in Mesoamerica,[151] as well, and their rituals could be every bit as bloody. In addition to animal and human sacrifices, the king himself, endowed with a divine (or at least semi-divine) status, often performed a bloodletting ritual where “kings voluntarily shed their blood as an offering on behalf of their people.”[152] Typically, a sensitive part of the king’s body was pierced, and then blood would be dripped onto bark paper and burned.[153] The smoke from the fire was then believed to open up a conduit between the natural and supernatural realm, through which divine beings would appear in vision, “communicating sacred knowledge, especially about future events and portents.”[154]

King Benjamin denied having any kind of special or divine status, and by so doing implicitly denied any efficacious power in his own blood (Mosiah 2:10, 26). Yet without bloodletting, he still interacted with a divine being (an angel) who revealed sacred knowledge about the future, telling Benjamin that there will be a future divine king whose blood will have power—and he won’t just bleed from one part of his body, but will bleed “from every pore” (Mosiah 3:7).

Benjamin’s revelation thus invokes both Israelite and Mesoamerican conceptions of blood sacrifice, and would have had quite the impact in its original ritual setting.[155]

New World Patterns of Revelation

Mark Wright noticed that about a generation or so later, a new pattern for revelation emerges. “Unlike Lehi,” Wright pointed out, prophets and others from Alma the Younger’s time, “did not receive their commissions according to [an] ancient Near Eastern pattern; rather, the calls conform to a pattern that can be detected in ancient Mesoamerica.”[156] Specifically, Wright has in mind “the accounts of individuals who are overcome by the Spirit to the point that they fall to the earth as if dead and ultimately recover and through that process become spiritually reborn and subsequently prophesy concerning Jesus Christ.”[157]

Among the contemporary Maya,[158] according to Bruce Love, “Most Maya shamans” report being called “through divine intervention; either through dreams, being miraculously saved, or through near-death experiences.”[159] Ethnographic work by Frank Lipp indicates, “Divine election occurs within a context of some physical or emotional crisis …. During the initiatory dream vision the individual may experience temporary insanity or unconsciousness, and a death experience whereupon he or she is reborn as a person with shamanic power and knowledge.”[160] While the individual is unconscious, healers and holy men may offer prayers and perform other ritual acts “on behalf of the critically ill individuals.”[161]

Wright compares this to the experience of various Book of Mormon prophets,[162] with Alma the Younger as the primary example of this pattern—falling to the earth unconscious for multiple days, while his father and other priests gather together and fast and pray over his body. Alma eventually awakens, “born of God,” and both spiritually and physically healed.[163] From that time forward, Alma frequently displayed prophetic knowledge and power.

This shouldn’t necessarily be taken to suggest that Alma and others participated in all shamanic practices and rituals, but merely to point out how the Lord may have used the expectations of the Nephites’ cultural environment when calling his prophets among them.

Revealing the Risen Lord in the New World

Wright also notes another subtle way Mesoamerican culture may be reflected in divine communication to Book of Mormon peoples.[164] It’s important to realize that while some early Nephite prophets had seen crucifixion in vision (1 Nephi 11:33), generally speaking that is not a form of death or punishment that would have been familiar to Book of Mormon peoples.[165] Nonetheless, “the sacrifice of a human being was the peak of Mesoamerican ritual,”[166] and the Nephites would have been aware of such cultural practices, perhaps even participating in them during periods of apostasy.[167]

While there were a number of different ways such sacrifices would be performed, one of the more common techniques was for a priest to “make a large incision directly below the ribcage using a knife made out of razor-sharp flint or obsidian, and while the victim was yet alive … thrust his hand into the cut and reach up under the ribcage and into the chest and rip out the victim’s still-beating heart.”[168] Wright thus proposes, “To a people steeped in Mesoamerican culture, the sign that a person had been ritually sacrificed would have been an incision on their side—suggesting they had had their hearts removed.”[169]

When Christ appears to Book of Mormon peoples at Bountiful, in contrast to his appearances in the Old World, “He bade them first to thrust their hands into his side, and secondarily to feel the prints in his hands and feet (3 Nephi 11:14).”[170] The difference is subtle, but for his audience, it may have been significant: the wound on his side would have been the most effective way to communicate to Mesoamerican onlookers that he had been sacrificed on their behalf.[171]

While considering each of these instances individually can serve to deepen ones understanding of the Book of Mormon, there is a larger point that can be made here, which is summed up by Nephi: the Lord “speaketh unto men according to their language, unto their understanding” (2 Nephi 31:3; cf. D&C 1:24). Wright correctly argues that language and culture are intrinsically linked, and thus speaking according the understanding of one’s audience requires cultural adaptation as much as it does linguistic accommodation.[172]

By observing how Book of Mormon modes of revelation diverge from biblical patterns and converge with Mesoamerican ones, we gain a deepened understanding of what it really means for the Lord to adapt his message to his peoples understanding, in all times and in all circumstances. This can, in turn, help us better appreciate why the Lord may have communicated with Joseph Smith in ways that seem odd or strange to us today, as well as helping us be more perceptive to how the Lord is speaking to us in the here and now.[173]

Conclusion

Recognizing that the Lord communicates to us within cultural expectations also begins to address why developing a mature, contextualizing approach to the Book of Mormon (and, of course, other scriptural works) is so important: if context matters to the Lord, then it ought to matter to us. In the brief time that I’ve had, I have tried to sketch out what it really means to study the Book of Mormon with mature historical thought, and illustrate the benefits I see in such an approach.

I want to be clear that I am in no way meaning to suggest or imply that everyone who takes a mature historical approach will reach the same conclusions I have, nor that everyone who disbelieves does so for “immature” reasons. All I am saying is that such an approach can build a more sustainable and rewarding faith in the Book of Mormon, one which is less vulnerable to the most common attacks made against it today online and in other venues.

To wrap up, I want to acknowledge that I know all of this can seem a little overwhelming. Believe me, I understand that not everyone can become a historian or dedicate themselves full-time to studying the Book of Mormon. I get that. With that said, let me offer a few words of advice and encouragement:

First, take your time. Scriptural and gospel study is supposed to be a lifetime pursuit, and developing a mature approach to scripture study is less about how much you know and more about having the humility to know when you need to learn more, and then patiently seeking out further information.

Second, maximize the time you do have. You don’t necessarily need to study longer, but you may need to make more of an effort when you do study. Whether you have an hour or just 15 minutes each day, you can maximize that time better by doing more than staring at the words on the page. Even by just taking a few minutes of that time to read up on some background and context can make a difference in how you understand what you are reading.

Lastly, utilize tools like Book of Mormon Central. Our goal is to try to make this easy for you by bringing all the resources on the Book of Mormon into one place, summarizing and synthesizing the best of that material into our KnoWhy articles, and producing multimedia content that makes it easier to understand.[174]

Ultimately, “put[ting] away childish things” will require, as Paul said, learning how to think about, understand, and talk about the Book of Mormon in new ways (cf. 1 Corinthians 13:12). While this may be difficult at times, based on my own experience, I am confident doing so can build faith, accommodate and even eventually resolve questions, and deepen understanding and appreciation for our keystone scripture.

Q&A

Q 1: Why would dog-horses not be translated as dogs?

A 1: That goes into all kinds of stuff on translation theory that I’m not interested in speculating on at this point. Like I said, I’m just trying to promote some possibilities. I’m not saying horses are dogs, I’m just saying, why did Native Americans so persistently associate dogs with horses? I don’t know. You would have to study it and maybe come up with your own answers.

Someone else pointed out, I guess is the point here, that the bison to buffalo shift is also similar to the fact that we call Native Americans “Indians”, which, they obviously aren’t people from India, so good point.

Q 2: What new evidence is found about animals in the Book of Mormon? Is the discovery of the origin of camels in Middle or North America helping?

A 2: I don’t see the Book of Mormon ever mentioning camels unless I’ve missed something, so I’m not sure. But it does maybe help in just the sense that we’re always learning more and more about the history of our world and where animals came from or where they were and when they weren’t there, and so you just, you never, like I said, you gotta just always keep an open mind to what new things could be found. If you’re interested in animals in the Book of Mormon though, there’s a book by Wade Miller on the topic, I’m pretty sure it’s in the bookstore.

Q 3: What evidence leads me to say the brass plates were engraved in Egyptian?

A 3: Mosiah 1:4 basically says they were, so that’s the evidence.

——–

Neal Rappleye is the Research Project Manager at Book of Mormon Central. He has published on the Book of Mormon in Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture and has an essay in Perspectives on Mormon Theology: Apologetics (2017), published by Greg Kofford Books. He has presented at the 2014, 2016, and 2017 Book of Mormon Conferences, formerly sponsored by the Book of Mormon Archaeological Forum (now part of Book of Mormon Central).

Endnotes

[1] For background on the El Amarna letters, see Richard S. Hess, “Amarna Letters,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 50–51; Lester L. Grabbe, Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?, rev. ed. (New York, NY: Bloomsbury/T&T Clark), 44–47. The letters from the king of Jerusalem are EA 285–290.

[2] EA 287: “land of Jerusalem” and “lands of Jerusalem.” EA 290: “a town of the land of Jerusalem, Bit-Lahmi by name.” EA 280: “‘Abdu-Heba [of Jerusalem] had taken the town from my hand.” All translations from W. F. Albright, “The Amarna Letters,” in The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 429–443.

[3] Margreet Steiner, “Jerusalem in the Tenth and Seventh Centuries BCE: From Administrative Town to Commercial City,” in Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan, ed. Amihai Mazer (Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 283.

[4] Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001), 7.

[5] Wineburg, Historical Thinking, 7.

[6] Wineburg, Historical Thinking, 18.

[7] I am paraphrasing Wineburg, Historical Thinking, 18: “rather than fashioning a context from the raw materials provided by these documents …”

[8] Wineburg, Historical Thinking, 21.

[9] Oded Lipschits, “The History of Israel in the Biblical Period,” in The Jewish Study Bible: Torah, Nevi’im, Kethuvim, 2nd edition, ed. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014), 2107.

[10] Linda Schele and David Freidel, A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (New York, NY: William Marrow, 1990), 55.

[11] 1 Nephi 1:4; 2:13; 4:4–5, 24, 27; 10:3; 11:13.

[12] 1 Nephi 1:4; Alma 10:3; 1 Nephi 5:14, 16

[13] 1 Nephi 3:31.

[14] 1 Nephi 3:3–4; 4:9, 20; 5:11–16; Mosiah 1:4 (cf. 1 Nephi 1:2).

[15] Obviously, the very existence of the Book of Mormon is evidence of their scribal training, but see 1 Nephi 1:2. See also Brant A. Gardner, “Nephi as Scribe,” Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 45–55.

[16] 1 Nephi 2:4; 3:16; 1 Nephi 17:9–10. See also John A. Tvedtnes, The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Springville, UT: Horizon, 2003), 78–97; Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “Lehi’s House at Jerusalem and the Land of his Inheritance,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 113–117. Also see Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:78–80.

[17] John L. Sorenson, “The Composition of Lehi’s Family,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, 27 March 1990, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 2:176 rejected the hypothesis that Lehi was a metalworker for this very reason.

[18] Steiner, “Jerusalem in the Tenth and Seventh Centuries BCE,” 284–285.

[19] Jacob Milgrom, in “Jerusalem at the Time of Lehi,” in Journey of Faith: From Jerusalem to the Promised Land, ed. S. Kent Brown and Peter Johnson (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), 37. See also Chadwick, “Lehi’s House,” 87–93; Mordechai Cogan, “Into Exile: From Assyrian Conquest of Israel to the Fall of Babylon,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World, ed. Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998), 325; Israel Finkelstein, “The Settlement History of Jerusalem in the Eighth and Seventh Centuries BC,” Revue Biblique 115, no. 4 (2008): 499–515.

[20] Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, Alexander Onn, Shua Kisilevitz, and Brigitte Ouahnouna, “Layers of Ancient Jerusalem,” Biblical Archaeology Review 38, no. 1 (January/February 2012): 38.

[21] Weksler-Bdolah, et al., “Layers of Ancient Jerusalem,” 41. Interestingly, one of the seals contains an image of a four-winged serpent, which the excavators interpreted as the biblical “fiery serpent” (p. 40). Note that Nephi changes the “fiery serpents” of Numbers 21:6, 8 to “flying fiery serpents” (1 Nephi 17:41). See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Say Serpents Could Fly?” KnoWhy 316 (May 22, 2017), online at https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/why-did-nephi-say-serpents-could-fly (accessed July 18, 2017).

[22] Steiner, “Jerusalem in the Tenth and Seventh Centuries BCE,” 284–285.

[23] Lidar Sapir Hen and Erez Ben Yosef, “The Socioeconomic Status of Iron Age Metalworkers: Animal Economy in the ‘Slaves’ Hill’, Timna, Israel,” Antiquity 88 (2014): 775–790, quote on p. 775. See also Neal Rappleye, “Lehi the Smelter: New Light on Lehi’s Profession,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 14 (2015): 223–225.

[24] See Philip J. King and Lawrence E. Stager, Life in Biblical Israel (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 2001), 164–176; Naama Yahalom-Mack and Adi Elyahu-Behar, “The Transition from Bronze to Iron in Canaan: Chronology, Technology, and Context,” Radiocarbon 57, no. 2 (2015): 285–305.

[25] Avraham Eitan, “Rare Sword of the Israelite Period Found at Vered Jericho,” Israel Museum Journal 12 (1994): 61–62, quote on p. 62. See also Hershel Shanks, “BAR Interviews Avraham Eitan,” Biblical Archaeology Review 12, no. 4 (1986): 33. For comparison to Laban’s sword, see William J. Adams Jr., “Nephi’s Jerusalem and Laban’s Sword,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 11–13; Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “All the Glitters is Not … Steel,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15, no. 1 (2005): 66–67; Matthew Roper, “‘To Inflict Wounds of Death’: Mesoamerican Swords and Cimeters in the Book of Mormon,” presented at the 2016 FairMormon Conference, August 4, 2016, online at https://www.fairmormon.org/conference/august-2016/inflict-wounds-death (accessed July 30, 2017).

[26] King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 310–315; William M. Schniedewind, A Social History of Hebrew: It’s Origins Through the Rabbinic Period (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 99–122.

[27] Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, et al., “Algorithmic Analysis of Judah’s Military Correspondence Sheds Light on Composition of Biblical Texts,” PNAS 113, no. 17 (2016): 4667, 4666.

[28] Aaron Demsky and Meir Bar-Ilan, “Writing in Ancient Israel and Early Judaism,” in Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity, ed. Martin Jan Mulder (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1988), 11, 15; David M. Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005), 173 n.231.

[29] Christopher A. Rollston, Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2010), 49, 72, 132 suggests that some potters and stonemasons may have received scribal training because stone and pottery were common writing mediums. In light of the Ketef Hinnom inscriptions (see below), it makes sense to extend this to metalworkers as well. Rollston also suggests more generally, “Some skilled craftsmen may have also been able to write and read” (p. 133).

[30] Seth L. Sanders, The Invention of Hebrew (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 97–98, 100, 107, quote on p. 107.

[31] Steiner, “Jerusalem in the Tenth and Seventh Centuries BCE,” 284.

[32] See Hugh Nibley, The Prophetic Book of Mormon, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Volume 8 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1989), 395–396.

[33] Though Nibley, Prophetic Book of Mormon, 384–386 makes an interesting argument in this regard for the Lachish archive.

[34] William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

[35] For popularly accessible discussions of these texts, see Clyde E. Fant and Mitchell G. Reddish, Lost Treasures of the Bible: Understanding the Bible through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museums (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2008), 405–407; Gabriel Barkay, “The Riches of Ketef Hinnom,” Biblical Archaeology Review 35, no. 4 (2009): 34–35, 122–126. For some of the more technical discussions of the inscription, its translation, dating, and context, see Ada Yardeni, “Remarks on the Priestly Blessing on Two Ancient Amulets from Jerusalem,” Vetus Testamentum 41, no. 2 (1991): 176–185; P. Kyle McCarter, “The Ketef Hinnom Amulets,” in Context of Scripture, 3 vols., ed. William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr. (Boston, MA: Brill, 2003), 2:221; Gabriel Barkey, Marilyn J. Lunberg, Andrew G. Vaughn, and Bruce Zuckerman, “The Amulets from Ketef Hinnom: A New Edition and Evaluation,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 334 (2004): 41–71. Some have argued for a later dating of the scrolls, most recently Nadav Naʾaman, “A New Appraisal of the Silver Amulets from Ketef Hinnom,” Israel Exploration Journal 61, no. 2 (2011): 184–195. For a response which reaffirms the 6th–7th century BC dating, see Shmuel Ahituv, “A Rejoinder to Nadav Naʾaman’s ‘A New Appraisal of the Silver Amulets from Ketef Hinnom’,” Israel Exploration Journal 62, no. 2 (2012): 223–232. The 7th–6th century BC dating remains the most widely accepted. See Jeremy D. Smoak, The Priestly Blessing in Inscription and Scripture: The Early History of Numbers 6:24–26 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 13–16.

[36] For previous discussions of these inscriptions in relation to the Book of Mormon, see Dana M. Pike, “Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Jeremiah and Lehi,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 213–215; William J. Adams Jr., “Lehi’s Jerusalem and Writing on Silver Plates,” and “More on the Silver Plates from Lehi’s Jerusalem,” both in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 23–26, 27–28.

[37] For more on this, see Book of Mormon Central, “Did Ancient Israelites Write in Egyptian?” KnoWhy 4 (January 5, 2016), online at https://knowhy.bookof mormoncentral.org/content/did-ancient-israelites-write-egyptian (accessed July 30, 2017).

[38] Stefan Wimmer, Palästiniches Hieratisch: Die Zahl- und Sonderzeichen in der althebräishen Schrift (Wiesbaden: Harraossowitz, 2008). See the map on p. 19 for all the sites such texts have been found, and for the total number of texts, see p. 20. For samples from Jerusalem, see pp. 62–65, 133–135, 161, 163, 164, 166, 175, 176, 177, 180, 187 (17 total). Dating of the texts can be seen for the individual entries.

[39] David Calabro, “The Hieratic Scribal Tradition in Preexilic Judah,” in Evolving Egypt: Innovation, Appropriation, and Reinterpretation in Ancient Egypt, ed. Kerry Muhlestein and John Gee (Oxford, UK: Archaeopress, 2012), 82–83. For comparison of this Judahite hieratic to Nephi’s statement about language, see Neal Rappleye, “Learning Nephi’s Language: Creating a Context for 1 Nephi 1:2,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 16 (2015): 151–159.

[40] See William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001), 107–108; William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003), 227–228; William G. Dever, The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: Where Archaeology and the Bible Intersect (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2012), 9. Dever’s methods were brought into LDS discourse on the Book of Mormon by Gardner, Second Witness 1:7–8. See also Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 47–52.

[41] See Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Text (New York, NY: Touchstone, 2001). Though this does not represent my own views on the subject, it is illustrative of how archaeology is often seen as undermining Biblical narratives.

[42] See, for example, Steiner, “Jerusalem in the Tenth and Seventh Centuries BCE,” 281–283; Finkelstein and Silberman, Bible Unearthed, 132–134. Of course, just as with Amarna, this absence of evidence does not prove there was no Jerusalem at this time. See Steven L. McKenzie, King David: A Biography (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000), 18–19; K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003), 150–154; Steven M. Ortiz, “United Monarchy: Archaeology and Literary Sources,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014), 254–255.

[43] See Edmund C. Briggs, “A Visit to Nauvoo in 1856,” Journal of History 9 (October 1916): 454; Nels Madsen, “Visit to Mrs. Emma Smith Bidamon,” 1931. These are each transcribed in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, 2nd edition, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Press, 2017), 141–143 (documents 38 and 40). See also Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jerusalem Have Walls Around It?” KnoWhy 7 (January 8, 2016), online at https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/did-jerusalem-have-walls-around-it (accessed July 19, 2017).

[44] Jews writing in Egyptian, writing on metal plates, Laban’s steel sword, and northern Israelites being in Jerusalem are all points that were criticized in Joseph Smith’s lifetime. On Egyptian, see Gimel, “Book of Mormon,” The Christian Watchman (Boston) 12, no. 40, October 7, 1831; La Roy Sunderland, “Mormonism,” Zion’s Watchman (New York) 3, no. 7, February 17, 1838. On metal plates, see La Roy Sunderland, “Mormonism,” Zion’s Watchman (New York) 3, no. 8, February 24, 1838. On steel swords, see E. D. Howe, Mormonism Unveiled: Or, A Faithful Account of that Singular Imposition and Delusion from its Rise to the Present Time (Plainsville, OH: 1834), 25–26. On northern Israelites, see Origen Bacheler, Mormonism Exposed Internally and Externally (New York, NY: 1838), 11.

[45] Terryl L. Givens, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture that Launched a New World Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 120.

[46] Ross T. Christensen, “The Place Called Nahom,” Ensign, August 1978, 73. Since then, several other old maps have been identified with Nehhm or Nehem on it. See James Gee, “The Nahom Maps,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Restoration Scripture 17, no. 1–2 (2008): 40–57.

[47] Warren Aston and Michaela Knoth Aston, In the Footsteps of Lehi: New Evidence for Lehi’s Journey Across Arabia to Bountiful (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994), 3–25. Another Islamic source which mentions Nihm, unnoticed by Aston, is al-Hamdānī’s al-Jawharatayn al-atiqatayn. See D. M. Dunlop, “Sources of Gold and Silver in Islam According to al-Hamdānī (10th Century AD),” Studia Islamica 8 (1957): 41, 43.

[48] S. Kent Brown, “New Light—‘The Place That Was Called Nahom’: New Light from Ancient Yemen,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8, no. 1 (1999): 66–68. For the dating of the altar to the 6th–7th centuries BC, see Burkhard Vogt, “Les Temples de Maʾrib,” in Yemen au Pays de la Reine de Saba, ed. Christian Robin and Burkhard Vogt (Paris, FR: Flammarion, 1997), 144; K. A. Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2 vols. (Liverpool, UK: 1994–2000), 2:18 (Barʾān DAI 1988-1); Alexander Sima, “Religion,” in Queen of Sheba: Treasures from Ancient Yemen, ed. St John Simpson (London, UK: The British Museum Press, 2002), 166 (DAI Barʾān 1988-1).

[49] Warren P. Aston, “Newly Found Altars from Nahom,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 2 (2001): 56–61.

[50] Norbert Nebes, “Zur Chronologie Der Inschriften Aus Dem Barʾān Temple,” Archaologische Berichte aus dem Yemen 10 (2005): 119 catalogues each of the altars mentioning NHM (DAI Barʾān 1988-2 [DAI Barʾān 1988-1], DAI Barʾān 1994/5-2, and DAI Barʾān 1996-1) as dating to the aSabB period, which is defined as ca. 685 BC on p. 115 n.34 (there is a typo that makes it seem like he is saying aSabB dates to 685 AD, but p. 114 and the overall context makes it clear that BC is the correct date). It’s on p. 115 that Nebes also dates the construction of temple 3 to 8th–7th centuries BC and suggests that a few dedicatory inscriptions date to this phrase (as opposed to the “classical” temple 4 phase from the 5th century BC, which is classified as aSabC on p. 114 n.32). Although Nebes never specifically defines the time range of aSabB, its association with inscriptions dated to ca. 685 BC suggests a late 8th to early 7th century BC dating, ca. 750–650 BC. Hence, the ruler Yadaʾil mentioned toward the end of the inscription could potentially be Yadaʾil Dharih I (ca. 740–720 BC) or Yadaʾil Dharih II (ca. 650–620 BC). See Kitchen, DAA 2:744 for the ruler chronology.

[51] These include Gl. 1637 (ca. 5th/4th centuries BC; Kitchen, DAA 2:208); CIH 673 (ca. 7th/5th century BC; Kitchen, DAA 2:139); and RES 5095 (ca. 8th–4th century BC). Haram 16, 17, and 19 (ca. 660/500 BC; Kitchen, DAA 2:120) may also make reference to Nihmites, though nh[mt]n is a restoration, and it’s been alternatively translated as “stone polishers.” In addition to these 1st millennium BC references, there are also several references to Nihmites in somewhat later inscriptions. See CIH 969 (ca. 3rd century AD; Kitchen, DAA 2:165); Ir 24 (ca. 270 AD; Kitchen, DAA 2:245); BynM 217 (ca. 4th century BC–4th century AD); BynM 401 (ca. 2nd–3rd century AD); YM 11748 (ca. 4th century BC–4th century AD). All of these can be found online in the CSAI database (http://dasi.humnet.unipi.it/), and this is where the dating of the text comes from (except those from Kitchen, DAA). The existence of other NHM inscriptions was first brought to the attention of an LDS audience in Warren P. Aston, “A History of NaHoM,” BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 2 (2012): 90–93. Nonetheless, many of these have been available in publications on southern Arabian archaeology and inscriptions for several decades, including one as early as 1942 (see CSAI database entries of bibliographic info).

[52] According to S. Kent Brown, “New Light from Arabia on Lehi’s Trail,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 113 n.68, Christian Robin indicates that “the tribal name NHM (and others) … has remained basically in the same place since it first appeared in inscriptions in the first millennium BC.” Brown is citing Christian Robin, Les Hautes-Terres du Nord-Yemen avant l’Islam I: Recherches sur la geographie tribale et religieuse de Hawlan Qudaʿa et du pays de Hamdan (Istanbul: Nederlands historisch-archaeologisch Instituut, 1982), 27, 72–74. Andrey Korotayev, Ancient Yemen: Some General Trends of Evolution of the Sabaic Language and Sabaean Culture (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995), 81–83 likewise cites Robin as indicating that the tribes of the Bakīl confederation have been in the same general area since the first millennium BC. According to Paul Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989), 24 (table 1.2), Nihm is part of the Bakīl confederation.

[53] Sima, “Religion,” 166–167.

[54] Vogt, “Les Temples de Maʾrib,” 144: “Le donateur Biʾathtar, originaire de la tribu de Nihm (à l’époque sans doute au nord du Jawf, aujord’hui au nord-est de Sanʾâ) …”. Thanks to Greg Smith for his assistance in translating this source.

[55] Peter Stein, Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München. Band 1: Die Inschriften der mittel- und spätsabäischen Periode (Tübingen and Berlin, GER: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, 2010), 23, fig. 1, quote from p. 22: “Eine Übersicht der genannten Orte sowie weiterer identifizierbarer Toponyme, welche in den bekannten Minuskelinschriften Erwähnung finden, bietet die beigefügte Kartenskizze.” NHM falls under “anderer in den Minuskelinschriften erwähnter Orts–, Stammes– oder, Landschaftsname” (“other place, tribal, or regional names mentioned in the minuscule inscriptions”) in the map key. Its inclusion on the map is based on its appearance in YM 11748 (ca. 4th century BC–4th century AD) as a nisbe (nhmyn), the same form as that used on the altars from Mārʾib (p. 22 n.43).

[56] Some skeptics, of course, will continue to split hairs, and say that this does not prove that there was a place called “Nahom” or NHM. It is important to understand, however, that tribes are frequently described and talked about as locations or places which you can move to and from and that have physical, geographic boarders that can be (and often are) mapped (see Dresch, Tribes, Government, 25, fig. 1.9, cf. 75–83). As Paul Dresch put it, Yemeni “tribes themselves are territorial entities” (p. 75) and “are taken to be geographically fixed” (p. 77). Stein, Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften, 735–736 included names of tribes (stamm) and tribal affiliation (nisbe) in the “toponyms” section of his index. This kind of conflation between tribe and place is evident in pre-Islamic antiquity, where inscriptions speak of going to and from a tribe as if going from place to place. See, for example, M 247 (ca. 4th–1st century BC), which speaks of traveling “on the route between Maʿin and Rgmtm,” where Maʿin is actually a tribal name. There are also several examples of using tribal names in “land of x” constructs. B-L Nashq (early 6th century BC), for example, speaks of going “into the land of Ḥaḍramawt,” with Ḥaḍramawt listed as a tribal name. In the same inscription, Ḏkrm, Lḥyn, and ʾbʾs in “land of Ḏkrm and Lḥyn and ʾbʾs” are potentially tribal names, though scholars are undecided on whether they are tribal or place names (such uncertainty is, itself, illustrative of how place and tribal names are used virtually indistinguishably). The construction “land of [tribe]” is really no different than Nephi’s “place called [tribe].”