Audio and Video Copyright © 2017 The Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research, Inc. Any reproduction or transcription of this material without prior express written permission is prohibited.

August 2017

[Note: Transcript lightly edited for clarity.]

We are going to talk about Book of Mormon internal constraints: what the book has to say about its own setting. But to begin, any discussion on Book of Mormon geography has to be couched in the context of the Church and BYU’s official statement that we don’t push pins into the existing maps today, and so consequently what I’m limited to in my research working with animation students at BYU and a virtual scriptures group that we’ve put together where we do work on the 3-D Jerusalem app—some of you have probably seen that come out. We’ve done Book of Mormon geography, we’ve done a recreation of Mormon’s cave, all of which can be put into a virtual environment to walk through like a videogame, that a lot of the older generation doesn’t see a lot of value in but the younger generation absolutely loves, seems to speak their language. But before I jump into the actual Book of Mormon internal geography, I just have to begin with Joseph Smith. It’s been claimed by many that Joseph Smith made up the book. Others saying that—oh this is my personal favorite—that Joseph Smith was inspired by the devil to write the book. To those people I always say, “Have you read the book, and have you seen what it says about the devil in the book?” Strange things to inspire to be written about you if that hypothesis were to be the case.

The other factor here, brothers and sisters, is a very simple one. If Joseph Smith is going to rise up in the frontier of the 19th century western New York and say, “I want to be a prophet, so I better start producing scripture.” Boy! This farm boy took it to a whole new level!

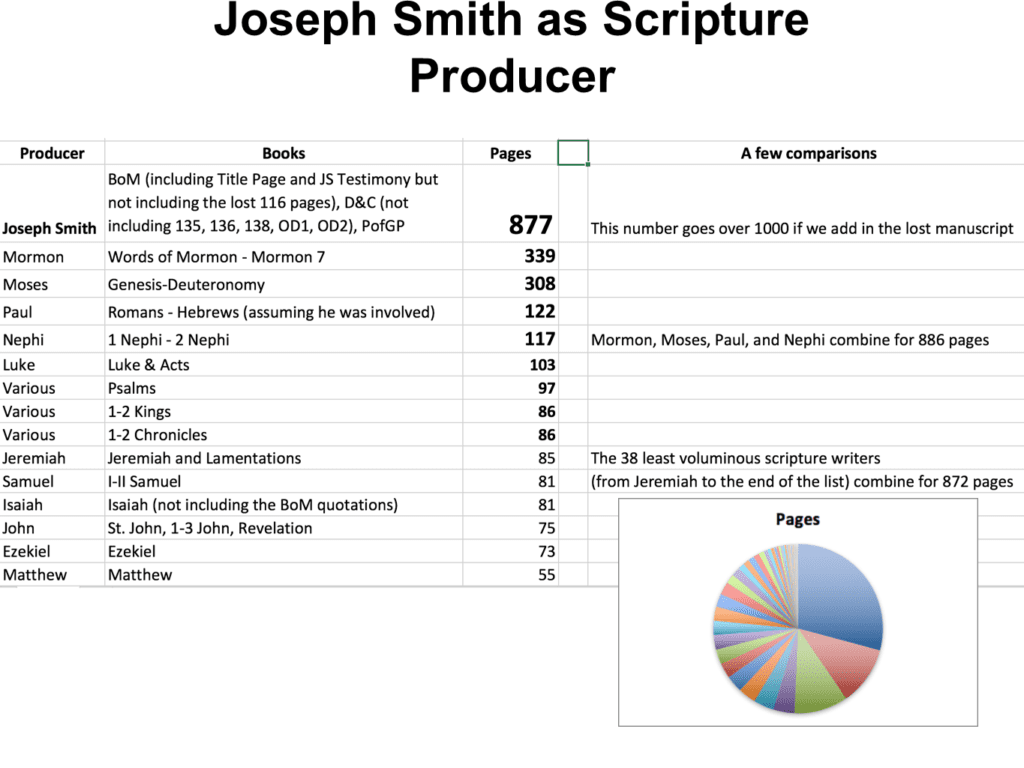

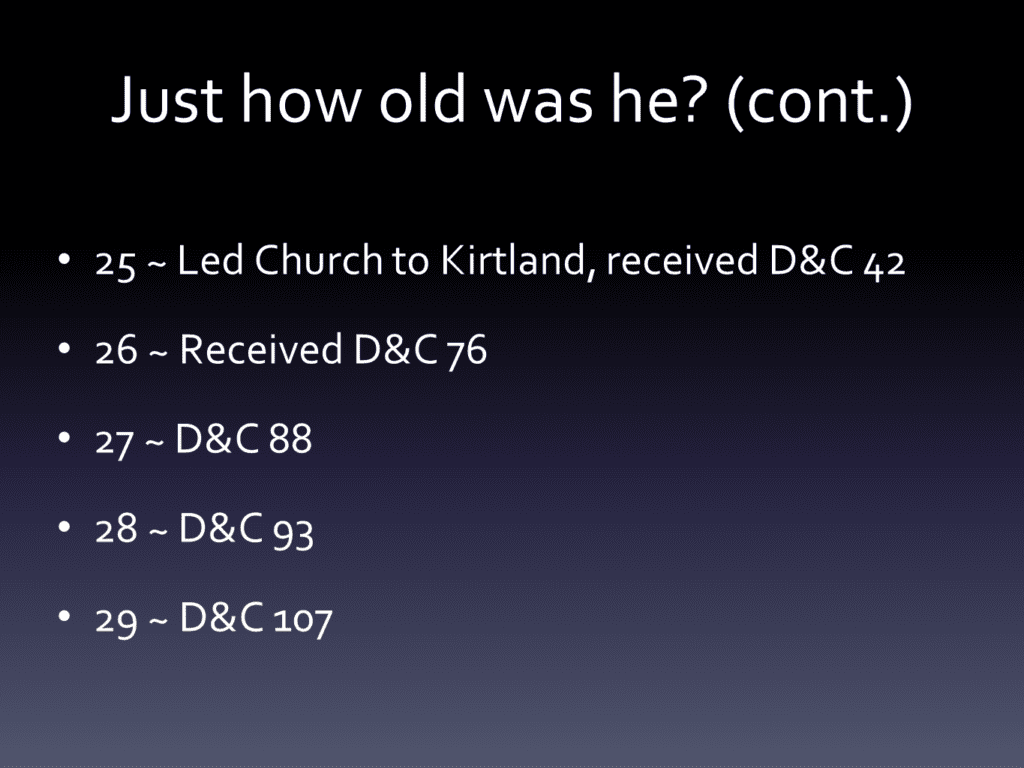

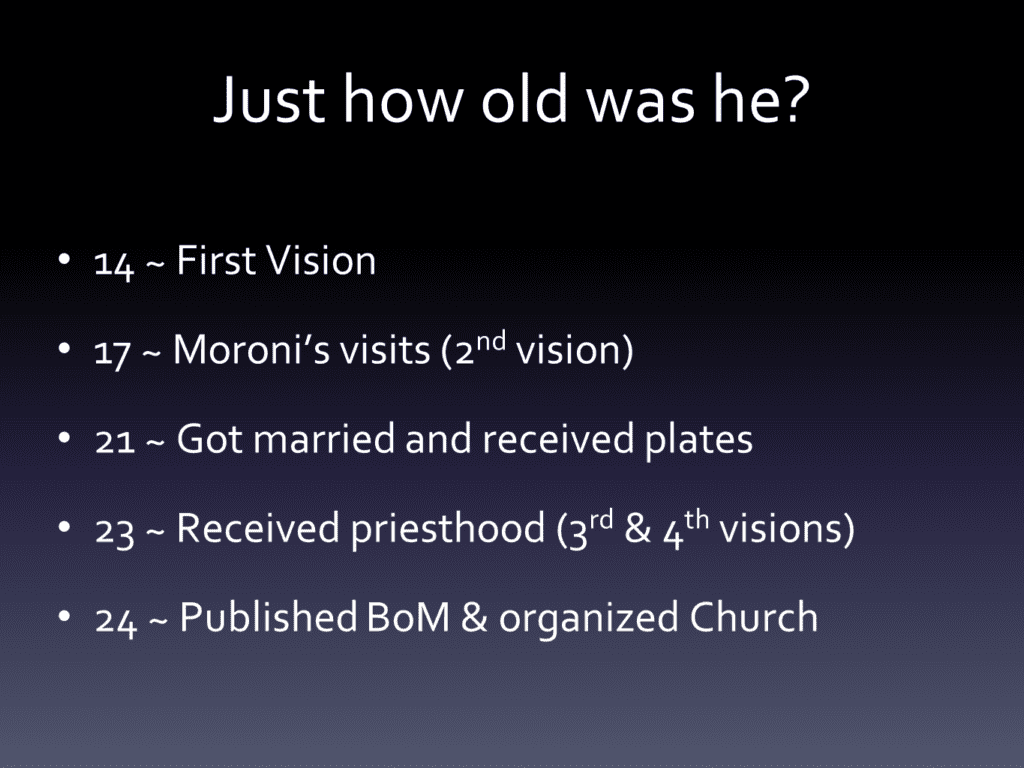

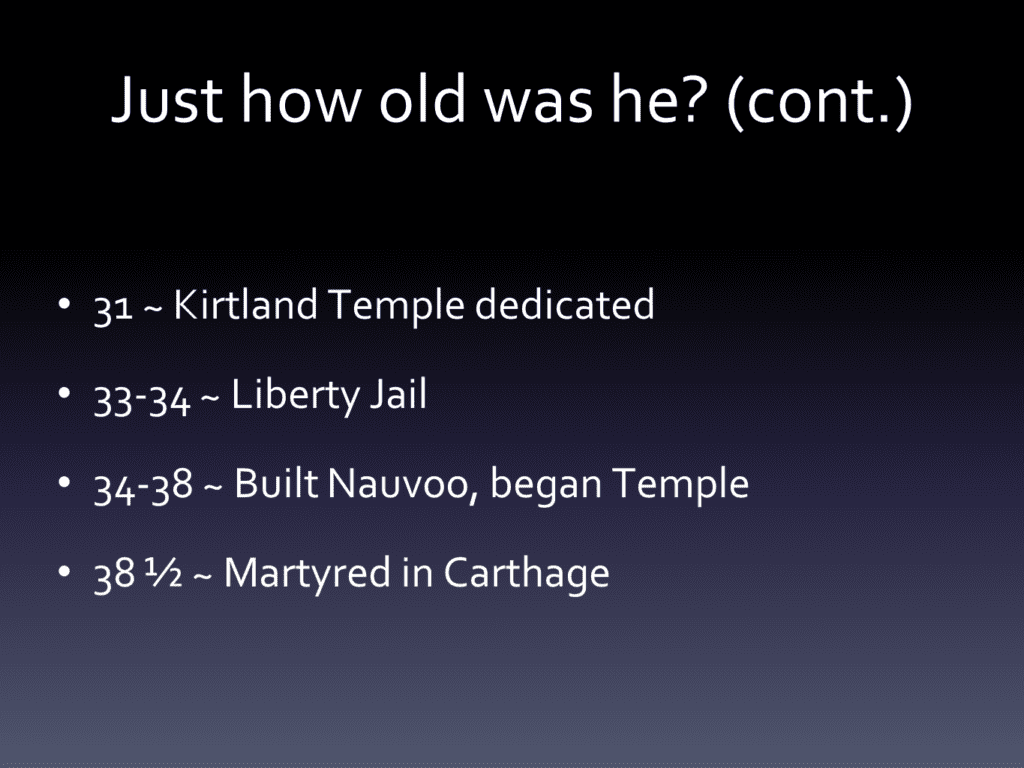

Not counting the 116 lost pages that would translate into approximately 145 of our current sized print pages, Joseph Smith is responsible for producing approximately 877 pages of scripture. The next closest scripture producer is Mormon at 339. After him you get Moses with Genesis through Deuteronomy with 308. You have to combine the first four after Joseph, scripture producers: Mormon, Moses, Paul and Nephi, to come up to 866 pages. Joseph with the 116 lost pages added in there takes his number to over 1,000. Off the charts! The world has never seen anything like this as far as scripture production. And some would say, “Well, he’s just a brilliant mind, brilliant thinker.” Just reflect for a moment on his age, we’re going to go through these very quickly before we dive into the actual geography that’s inside of the Book of Mormon that came through him. Fourteen years old at the first vision, everybody knows that. Seventeen at Moroni’s first visit, we know that. Twenty-one, he got married and that’s when he received the plates. What were you doing when you were 21? He was 23 when he had those 3rd and the 4th visions where he received the Priesthood. Twenty-four when the Book of Mormon was published and when he organized a Church. What had you done by the time you were 24? Twenty-five when the Church is going to Kirtland. He’s 26 years old when Doctrine & Covenants 76 comes through him. Twenty-seven when section 88 was delivered. Twenty-eight when section 93 came. Twenty-nine, you can just follow this. Thirty-one Kirtland temple dedicated. He has his 34th birthday when he’s in the Liberty Jail. Thirty-four to 38 he’s building up Nauvoo and beginning the construction on that temple there, and he’s martyred when he’s 38 and a half.

Brothers and sisters, four years ago when I hit that same age, 38 and a half, I marveled to look at the number of missions, the number of scripture pages produced, the number of incredible, mind-blowing revelations and doctrines that came through this frontier farm boy with, we always say, a three-year formal education. But keep in mind, those were three years of formal education on the frontier, in the 19th century. Basic reading, writing and arithmetic. Most of you are very familiar with this so we’ll just go very quickly. Emma’s reflections way later in life, I get that, it was 1879 when she has this interview with her son and she says, Joseph “could neither write nor dictate a coherent and well-worded letter, let alone dictate a book like the Book of Mormon” [or no doubt the Doctrine and Covenants or Pearl of Great Price]. She then testified, “It is marvelous to me, a marvel and a wonder, as much so as to anyone else” (“Excerpts from Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints Herald, 1 October 1879, 290). She goes on to talk about the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. “I am satisfied that no man could have dictated the writing of the manuscripts unless he was inspired; for, when [I was] acting as his scribe, [Joseph] would dictate to me hour after hour; and when returning after meals, or after interruptions, he could at once begin where he had left off, without either seeing the manuscript or having any portion of it read to him. This was a usual thing for him to do. It would have been improbable that a learned man could do this; and, for one so ignorant and unlearned as he was, it was simply impossible” (“Excerpts from Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints Herald, 1 October 1879, 290).

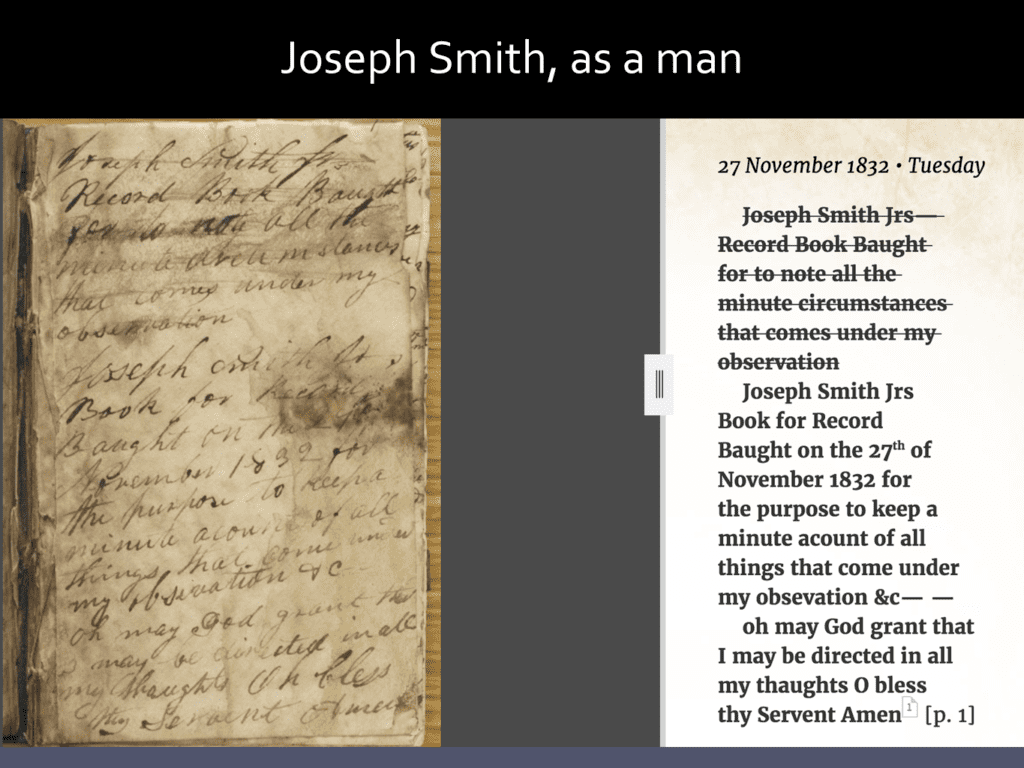

This is also something many of you are familiar with, but just as one more, the final set-the-stage aspect here. Joseph Smith, in November 1832, decided to write a personal journal, begin his personal record. Keep in mind the date November 1832. The Book of Mormon’s been published since spring of 1829. Quite a bit of time passed. Look at page one. “Joseph Smith Jrs—Record Book Baught for to note all the minute circumstances that comes under my observation.”

And you can see that he wrote that in his own hand, didn’t like it apparently because he crossed it out, said, “Let’s try again.” You can picture Joseph the farm boy looking at that and saying, that don’t read good, crossing it off and saying, let me try again. “Joseph Smith Jrs Book for Record Baught on the 27th of November 1832 for the purpose to keep a minute account of all things that come under my observation &c— — oh, may God grant that I may be directed in all my thaughts O bless thy servant Amen.” Little bit better, don’t you think? Second draft was better than the rough draft. One of the interesting things about the Book of Mormon is what went to the printing press. The printer’s manuscript was what? Oliver’s doing his best to copy exactly the rough draft. Now, this doesn’t prove anything to anyone. I’m just saying that as you compare Joseph Smith the man to Joseph Smith the prophet, seer, and revelator, the instrument in the hands of God, there is a total and complete difference. This reads like a farm boy. The Book of Mormon doesn’t read like a farm boy.

One of the amazing things is that, all of the people who talk about the translation process, none of them mention Joseph having any kind of external help beyond the interpreters. No books, no charts, no maps, no notes, no extensive sets of resources to rely on to make sure he’s keeping things straight. Which, by the way, once again I’ll just say, if you’re going to make this up, good grief, don’t create 531 pages of a new scripture! Just do 1 Nephi. That’s good enough! He’s a prophet, look, just give us a few pages. 531? And you get to the end, finally you finish with this convoluted, difficult record with Lamanites and Nephites and Mulekites (and they’ve mentioned this other group, the Jaredites), you finally finish with Mormon chapter 8, be done! And then Moroni finishes it off with chapter 9, be done! No! Let’s open it up and start the history of the Jaredites with Ether and keep going. Peculiar for a farm boy if he’s trying to just be a prophet. The volume that’s produced is remarkable.

Now let’s jump into the geography. You can number the references in the Book of Mormon, the internal references to geography, geographical locations or anything that has to do with geography, depending on how you parse it out, it’s going to come out somewhere between 500 and 550 references to geography. You’ll notice that, on the small plates, most of the geographical references are very simple to interpret because they’re Old World: they’re Jerusalem, they’re Red Sea, they’re across the desert over there. But once Nephi gets us to the land of the first inheritance, his interest in giving us any kind of geographical markers or any kind of north-south or ups or downs, he just doesn’t care about the geography.

So we don’t pick up geography in the New World largely until we get to Mormon’s abridgements. And Mormon, the Nephite chief captain, he cares a great deal about geography and he’s going to go to great lengths in some sections to tell us about the geography, which is very interesting. You’ll notice in a reading of the Book of Mormon, which area do you get the greatest geographical description of? You’ve got choices: the land of Nephi, the land of Zarahemla, or the land of Desolation. The vast majority of our references come to us in the Book of Mormon regarding the land of Zarahemla.

This part, which is predominantly the Nephite lands throughout the history. Mormon knows quite a bit about the land of Desolation and he knows a lot about the land of Zarahemla. Most of what he’s writing about takes place in the land of Zarahemla. Consequently, you’re going to get a lot of detail with north, south, east, west, and up/down kinds of descriptions in the book. Here’s the amazing thing. 500 to 550 references to geography in the book with stories that are often separated by hundreds of pages having to do with the same geographic locations, and somehow it just stays 100% consistent.

Brothers and sisters, I can only find two instances in the book where it looks like Mormon, either I can’t figure out what he’s saying or what it means, or it looks like he might have gotten something messed up a little bit, or he said something a different way than maybe what he intended, which isn’t unusual. We see him do that in his normal narrative flow as well. You’ve all seen those, right? Where Mormon messes up? But I love telling my students, “This book is so good that even when it’s wrong, it’s right.” For instance, you’re probably familiar with the passage in Alma 24 when Mormon tells you, “And thus we see that they buried their weapons of peace.” And then he says, “Or, they buried the weapons of war, for peace.” You unpack that and you say, “What in the world just happened there? What did he say that for?” And you picture him scratching or engraving in the metal plates, and I know everybody in this room has done that, where you’ve been writing along or typing along and your brain gets ahead of your hands, and what happens? You write things out of order. I can picture Mormon looking down the corridor of time at you with your laptops and your word processors and your erasers and him going, “Oh, if only you knew how hard it is when you let your head get ahead of your hands.” So he has to fix it with words.

To me, that might not prove anything to anybody else, but to me, if a farm boy is making the story up, and if he says to his scribe, “Thus we see that they buried their weapons of peace,” what would any farm boy do at that point as he recognizes, “Oh, whoops! Scratch that Oliver, take that out. Make it, ‘Thus we see they buried the weapons of war, for peace.’” But if he’s translating an ancient record, he’s not going to scratch it; he’s going to keep it.

I love the fact that a God on High allowed Mormon’s humanness to come through the work to show us what should we as humans do when we inadvertently mess up as well. You recognize you messed up, you fix it, and then you move on. And he never wallows in the mire; he leaves that for Moroni to do. Moroni’s the one who keeps complaining about what a poor, lame writer he is. How many of you have ever gotten to the writings of Moroni and thought to yourself, “Oh great, here we go, now it’s Moroni. Let’s slog our way through this lame author.” None of you have ever done that because you see Moroni was focused on what he perceived as a weakness, and his weakness as seems to me to be revealed by God was, “Moroni, your weakness isn’t your writing. Your weakness is you’re comparing yourself to the Brother of Jared’s writing. Stop it! My grace is sufficient. Do your best and I’ll make it a strength, it’ll become strong.” And you’ll notice that post-Ether 12:27, never again does Moroni compare himself to anybody else’s writing; he just writes. His weakness became a strength. I love it.

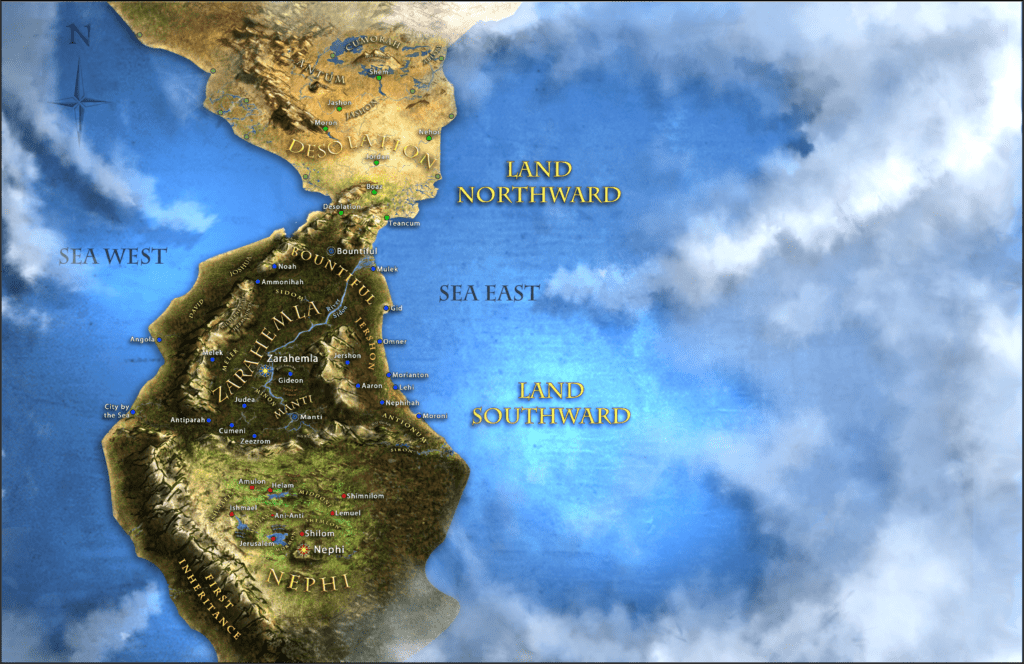

So, with that foundation, let’s dive into this book and look at some of these passages that have to do with geography and show you the complexity of what’s going on internally. Again, I’m going to say very simply that we don’t get involved in the arguments of, “Is it in the heartland? Is it in Mesoamerica? Is it in the Baja?” Or as some of you are probably aware, there are theories… Now you can buy the book on Amazon that believes the Book of Mormon took place in Africa, the book’s available. Sri Lanka, Malaysia—there are theories all over the world—and in South America. So what we’ve done is just tried to do the best we can with the internal references and any time you start making an internal map there are going to be errors. We get that. So you can stretch, squeeze, compress, twist, contort, and turn these internal relational locations to fit whatever external geography you prefer, it’s totally fine. But let me show you a couple of examples.

So the first major reference to geography is going to come, obviously in, the biggest geographical description is going to be Alma 22, verses 27–35. So it’s here where you get Mormon, the Nephite chief captain, who knows the land very well, pausing in his narrative to say, “Let me kind of describe the land.” And in there, he describes the land southward, which is nearly surrounded by water, separated from the land northward by a narrow neck of land, and he describes that there is a narrow strip of wilderness that separates the land of Nephi on the south from the land of Zarahemla on the north in the land southward. And he talks about a wilderness on the west of Zarahemla and on the east of Zarahemla and on the west of Nephi, near the land of the first inheritance. He never once mentions anywhere in the book a wilderness on the east of the land of Nephi. So on our map we didn’t put a wilderness depiction there.

From here, from that basic description, now we dive into a whole bunch of other geographical issues surrounding the Book of Mormon. You ready for this? You’ve got first and foremost migrations. You’ll notice that everything in the book seems to want to press northward. You will find that there’s not a single major migration of people until way later when Mormon himself migrates southward, his dad brings him from the land of Desolation down into the land of Zarahemla. Every other migration in the Book of Mormon goes which direction? North. Every single one. Which is odd for a farm boy, if he’s making this up from western New York. If you’re going to migrate people, which direction are you going to migrate them? West and south. You’re going to go out towards the frontier. Everything’s west. You don’t migrate north in Joseph’s day. And yet every single migration, the big ones, go north! All of them! In Alma 63 verse 4, you take 5,400 men and their women and children from the land of Zarahemla, after the major war chapters have closed, and they’re done; they’re done with the wars. And they migrate and it says they went northward.

Then you turn over to Alma 63:5–9 and you get Hagoth, the man who goes to the west sea near the narrow neck of land in the land Bountiful, somewhere here that separates from Desolation, somewhere here he builds an exceedingly large ship, and it tells us that a whole bunch of people get on that ship and where did they go? They sailed northward. In your external geography preferences wherever you want the book to take place, you’ve got to make sure that your west sea allows for Hagoth to take an “exceedingly large ship” and sail a big group of people northward and then come back, pick up another group, build more ships, and they sail away and you never see them ever again; they’re gone from our story. We have no idea where the Lord took them because the Book of Mormon stays centered in Zarahemla. This opens up all kinds of options for research. Where would you expect to find Lamanite and Nephite artifacts? Oh, and by the way, lots of Lamanites left as well! The descendants of Ammon, the people of Ammon, the Anti-Nephi-Lehites? In Helaman chapter 3, you get major migrations. Helaman 3:3-14 it just describes group after group after group leaving the region that the Book of Mormon’s talking about and going northward and it goes as far as to say that they went exceedingly great distances northward, even until they came to a land covered by many waters and rivers. And then from there it says they spread into all parts of the land that were not inhabited. Where would you expect to find Nephite/Lamanite remains or artifacts or whatever you want to look for—language remnants, if possible? They’re going to be spread and scattered through native populations throughout this time period. But all of them go north. Very odd for a frontier, New York story.

Which, by the way, I just have to throw this in here. If Joseph Smith were simply trying to make a story to show that the Native Americans were Israelite, then he sure did a poor job at describing Indians as Joseph and his contemporaries in the 19th century would have known them. There’s not a single tepee in the Book of Mormon. There’s not a single powwow. There are no squaws, no braves, there’s no headdress with feathers, there’s no tomahawk-throwing. Everything that would just scream “Native American!” to the 19th century New York frontier, Joseph did a really good job of leaving most of that out. You do have mention of tribes. You do have mention chiefs and splitting into the tribes, and warfare. But beyond that, all of the things that traditionally speak “Native American,” he totally left that out of the book.

OK, another thing, in the book, the geography is 100% consistent when it comes to speaking of Nephi and Zarahemla, the two lands. You’ll notice that in the book of Omni, King Mosiah I, the father of King Benjamin, he is commanded by the Lord to take all those who will follow him and they leave Nephi and they go, it says they travelled many days in the wilderness and went down to the land of Zarahemla and discovered this people. It’s approximately a 20-day journey based on Alma and Helam’s group later on, going from Nephi up to Zarahemla. So less than a three-week journey in the wilderness and you’ve got these two populations, the Mulekites and the Nephites, who have been coexisting within three-weeks journey of each other for 350 years and they didn’t know about each other; they had no concept that there was another… They discovered them. Which creates all kind of fun discussions you can have about the political nature of the Book of Mormon in that here you get this group of Nephites that are totally outnumbered by the Mulekites and it’s the Mulekite home-turf that they’ve been on for all these years, centuries. The Nephites show up and the Nephites have the records. The Nephites have a history. The Nephites hold the story. The Nephites control the pen. The Nephites consequently take over the power. The Mulekites don’t retain the throne, it goes to Mosiah I. And you’ll notice how this could possibly create all kinds of issues for the rest of the Book of Mormon regarding Kingship and rights to the throne and king-men and people saying, “We are of noble birth.” Keep in mind who the Mulekites descended from. The son of Zedekiah; they’re of the tribe of Judah, the tribe appointed to reign as Kings and here you get these Manasseh-ites showing up and they’re now kings. Any wonder that Mosiah II says… Let’s go to Judges, let’s shift away from kings and go to judges and stop some of this arguing and fighting. We know there are issues when King Benjamin’s the king, because people come and he wants to give them one name that they can be known by, he wants to unite them. And so you see all of these issues coming to play in this book and it doesn’t matter which lens you want to look at the book through, whether it’s geography or cultural or political or… It doesn’t matter. This book is remarkable for a rough draft from a farm boy in upstate New York with three years of formal education.

Alright, skipping over some of these because we don’t have time for all of these, I want to get to some good ones. OK, let’s go to Mosiah, the migrations in Mosiah. Keep in mind that here you’ve got King Mosiah I, who left, went this distance down to Zarahemla. Zarahemla’s always down, Nephi is always up, every single time, which is really bizarre because he always talks about going northward down to Zarahemla. Any 19th century person, if you’re going northward, you’re going to be going up, but the Nephites don’t have satellites and they don’t have pictures from drones to be able to see elevations and locations. They’re going by what they can see. Land of Nephi’s clearly highland, land of Zarahemla’s clearly lowland. So wherever you want to place the Book of Mormon in external geography, just make sure that if you’re going from one to the other, you’re going downhill, or at least perceive to be going downhill to the person on the ground. So what happens is that then you get Zeniff’s group that came back down, then you get the fun story with Noah, and Alma’s people are going to be getting baptized at the waters of Mormon, which is a day’s journey out and back from wherever your city of Nephi is. Your waters of Mormon need to be within a day’s journey of your city of Nephi, they’re close. Then he’s going to travel eight-days’ journey, Alma, and we assume that it’s in a northward direction. We don’t know because he doesn’t give us a ton of detail with the land of Nephi, so these are pretty arbitrary. But we know it’s probably a northward direction when he stops and builds a city at the place called Helam. This won’t get you into heaven, but it’s just kind of fun to know, on the original manuscript, the word was Helaman but it got changed in the typesetting of John Gilbert, he changed it from Helaman to Helam. So the first guy who gets baptized was Helaman and the city is called Helaman in the original manuscript but it ends up in our Book of Mormon as Helam. That won’t get you into heaven, but it’s an appropriate name because those people had struggled with some things and they were hurting and Alma wanted to Helam, so there you go. My students have to pay tuition for this kind of humor, so count yourself lucky.

Now wherever you want your geography to be, notice that there’s a 24-year period that passes where you get Limhi’s people who are nearly immediately brought into slavery and to bondage in the city of Nephi and Shilom to the Lamanites. So for 24 years you get this incredible story in Mosiah chapters 21 and 22 about them trying to overcome their slavery and their bondage on their own. It doesn’t go so well for them. Three failed attempts and each attempt their slavery and bondage gets worse and worse and worse. Finally, probably facing near extinction, the people say, “OK, what should we do now?” They turn to God. After 24 years they turn to God. “Please deliver us!” Well, it just so happens that in that same time period Ammon comes to the king up here. Ammon’s not even a Nephite! He’s a descendant of Zarahemla; he’s a Mulekite. He’s never been to the land of Nephi before. He says, “Hey, some of our people left like 80 years ago, our ancestors. We’ve never heard anything from them. Can we go see how they’re doing?” And they’re given permission and they wander for 43 days in the wilderness before they finally find the Nephites, the Limhi group, and they eventually get them out of bondage.

Now the funny part of this story is that wherever your geography is placed in the Book of Mormon, you’ve got to make it such that you could have this big group of people leaving here heading northward under Ammon and the 15 strong men’s direction, and after two days, your Lamanite army following this big group of people with all their flocks and their herds, loses track of them in the wilderness, whatever your terrain’s going to look like. And they don’t just lose track of them, they lose track of any direction! They can’t figure out how to get back to where they came from! They’re lost! They’re struggling, they’re wandering. They can’t even get back to the city of Nephi. And so they keep wandering and they find Amulon, the wicked priest, and his other wicked priests, and the stolen Lamanite brides. That story happened over two decades ago, and so now you’ve got this well-established city and they say, “Oh, don’t kill our husbands, it’s all good, we’re all family now.” And they say, “Amulon, how do we get home?” And Amulon says, “I have no idea.” And they start wandering together and they, lo and behold, come across Helam. And Alma knows how to get them home, and he tells them exactly how to get home and they still bring him into bondage.

Now, brothers and sisters, this is an interesting thing that not just geography stuff but the human side. Here you get Alma, who is brought into bondage. Limhi had been in bondage for 24 years and it was miserable. Lots and lots of people died and their slavery was horrible and the taxes were terrible. Alma’s people get brought into bondage because Abinadi had prophesied, “If you don’t repent, you will be brought into bondage.” They didn’t, so they do need to be brought into bondage, but it’s not a hard bondage. And so, in a matter of a few months, less than a year, Alma’s people get delivered from their bondage, and then they make the final journey down into Zarahemla.

There are four major entry points between these two that are mentioned in the text. There could have been others, we just don’t have access to any story that tells them. You have this eastern flank here over by Antionum. The city of Antionum is where the Zoramites live. You’ll remember the dream-team of missionaries: Alma and his sons, and Zeezrom and Amulek, they go on this mission to try to prevent the Zoramites from becoming Lamanites. You can see why they wouldn’t want to lose Antionum. You’ve also got an entrance into the land of Zarahemla through Manti. You’ve got one through Antiparah and then you’ve got one way up through Ammonihah. Interesting that, of those four entrances, Ammonihah is in a place where they feel very, very comfortable, very protected. Fascinating when you get to the book of Alma because Alma goes on a few missionary jaunts here and there. He starts in Zarahemla with Alma 5, then he goes east of the river Sidon to Gideon, then he comes back home, and then it says he went a day’s journey west of Sidon. It could have been down here, it was over bordering on the wilderness wherever it is, and then he tells you that he goes three-days’ journey northward to Ammonihah. And when he tells these people, “If you don’t repent, you’re going to be destroyed in one day,” they laugh him to scorn. Looking at the map you can see why they might laugh him to scorn. We don’t know exactly where it is in existing geography. We know it’s three days’ journey north of Melek, and Melek is west of Sidon near Zarahemla, so we know they’re pretty close to the land Bountiful. So it’s interesting that you now get stories combining… This is where I’m talking about the complexity of this story and these people and the number of pages and the number of situations going on, and it stays consistent.

Remember that while Alma the Younger is doing his 14-year preaching and ministering and chief-judging at the first part up here in Zarahemla, the four sons of Mosiah—his former drinking buddies I guess you’d call them—they go on their mission down to the land of Nephi. After converting people in seven cities, those people converge on, it seems, the land of Ishmael where Ammon had begun. And it’s the last reference to a location, before Alma 24, is in the land of Ishmael so we would assume that’s probably where this is taking place, where they dug the deep pit, threw their swords in, and then they go out and worship God in the very act of being killed. That army that came against them gets so tired of killing people who are thanking them and praising God in the process of dying that they say, “Enough! Let’s go fight Nephites!” Where did they go? They went to Ammonihah. And they wiped out the city Ammonihah in one day, fulfilling Alma’s prophecy. The very guys who had been killing Ammon’s converts are now killing the people who rejected Alma. Interesting that years later… So these Anti-Nephi-Lehites leave, and about five years later, Amalickiah shows up. So all that story of Amalickiah’s rise to power… The poor Lamanite king, he had only had his throne for about five years before he gets killed by Amalickiah, and Amalickiah first desire is, “I’m going to take over the Nephites.” So he sends his army and where does he send them? Ammonihah, because that’s the last place we went where we had great success as Lamanites, perfect! They go up there and what do they find that Captain Moroni had anticipated all this, so we’ve now fortified all the cities and this is the very worst battle in the entire history of the Book of Mormon. Chapter 49, verse 23. Over 1,000 Lamanites die; not a single Nephite died. They come home and Amalickiah is furious with them and he curses God and he says, “I swear I will drink Moroni’s blood.” I don’t mean to make any of you sick, we just ate lunch and all, but it’s interesting that Amalickiah took his army at that point and he entered the land of Zarahemla through Antionum, through Moroni down here in the corner, and in chapter 51, Mormon tells you the cities that he took one after another after another heading northward, and he lists them and he says, “All of which were on the east seashore.” So wherever you want your Book of Mormon to take place, your Moroni has to be lowest on the east seafront, followed by Lehi, Morianton, Omner, Gid, Mulek. That’s just an internal constraint, and he stays consistent throughout the book in the usage of those. And he’s making his way over to Bountiful when Teancum heads him off. So wherever your Bountiful is in the external Book of Mormon model, it needs to be within a region where Teancum can start a battle between Mulek and Bountiful, and Mulek is on your eastern seashore. They have a battle and it’s so bad and it’s so hard that they have to stop the battle for the night and it says that Amalickiah’s men camp on the seashore, on the beach, that night. And Teancum’s men camp in the borders of the land Bountiful that night. So your borders of the land Bountiful seashore have to be close enough that Teancum can wake up (not fall asleep, actually), get his servant, and say, “Let’s go!” And they go down to the beach and they find King Amalickiah sleeping in his tent and throw a javelin through his heart. Once again I don’t want to make you sick, but Amalickiah had sworn with a wrathful oath that he was going to drink Moroni’s blood. Brothers and sisters, the last thing Amalickiah would have done in mortality, laying there in his sleep as a javelin pierces his heart and lung—would have caused blood to pool up, as he’s laying down, in his throat—the very last thing Amalickiah would have done in mortality would have been choke on and drink his own blood.

Little things like this that just keep happening all over this book, it’s just incredible how this story unfolds, that God’s work is going to move forward. There are enemies, there are struggles. So to finish off my discussion here, here we sit, year’s 2017. We’re at a FairMormon conference. This Book of Mormon story is alive and well! The attacks are coming from all different angles! They might change their weaponry, they might change their tactics or their techniques, but the enemy is there! And the very book itself shows us that we don’t need to fear the evil curses or the evil threats, we need to follow Captain Moroni and Lehi and Teancum’s example of… Yes, they lost some ground. But Captain Moroni didn’t throw his hands up in the air and say, “OK, fine. We give up.” The stripling warriors over here in Judea in chapter 56 and 58 and on, they didn’t give up because they had lost Manti, Zeezrom, Cumeni, and Antiparah. They figured out, “How do we retake this ground? How do we redefine this as Nephite soil rather than letting the devil define it as his own?” And that’s what I see as the great work that FairMormon does as an organization, and others—Book of Mormon Central and MHA and so many other organizations—to help fight this battle that is alive and well in this book that came through a farm boy in rural upstate New York in the 19th century.

Let me finish by saying I don’t have a testimony of Joseph Smith the farm boy. He was a farm boy and we’ve seen his works, we’ve seen some of the things he did, some of the things he produced as a farm boy. But every time God picks up that farm boy and uses him as an instrument in His hands, I have an absolute testimony that Joseph Smith is a prophet and seer of the Lord, and I bear that witness in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Q&A

Q1: “Don’t some major geographical details like the evidence of vulcanism in 3 Nephi and a Sidon that flows north immediately rule out geographical models?”

A1: So again, you’ll remember our first presentation today, Ben Spackman, the idea is that you have a black box and everybody has that black box. I have a lot of these same items in my black box. But I’ve talked to people, one-on-one, from a whole bunch of different persuasions, I’ve seen tears in their eyes as they say how much this book means to them as a testimony of God’s love for them and their people in South America. Or, my son is now serving in Guatemala City Central Mission, right in the heart of most of the events that some people would put as the land of Nephi, and he tells of people who just love the fact that this is a story of their land. And others who have done extensive research on Baja and the heartland and so I would just say, leave options open. So what I try to do is look for plausibility in all kinds of places.

Just one little quick example: Baja. The Rosenvalls have done incredible research. Does a lot of the geography work for most people? Maybe not. But wow, they’ve got some amazing things like plant DNA that non-LDS scientists have sequenced for plants in Baja that they say match perfectly with DNA-sequenced plants from Oman. And they can’t figure, the scientists are like, “How did plants from Oman get over to Baja that match their family? How does this work?” Meaning, I would look for plausibility and possibility rather than shutting down options until the Lord tells us exactly where it is. That’s where I go.

Q2: “Where can I get a copy of your map?”

A2: All of the stuff that we’re producing at BYU as a virtual scriptures group, Taylor Halverson and I, with Seth Holladay from the center for animation, we hire all of his students to do all of our pretty stuff, can be found at virtualscriptures.org. And unfortunately the students aren’t here right now because they’re away at school and so a lot of the site is still struggling, so just be patient. The wording’s bad but you can get some of the resources there and we’ll keep updating it and keep making things better as we go.

Q3: “Do you have any geographical evidence that suggests that Nephi/Lehi landed on a western shore or an eastern shore?”

A3: The best evidence simply comes from that line in Alma 22 where it talks about on the west wilderness of the land of Nephi, near the land of the first inheritance. So it would be really unusual for him to say, on the west wilderness, near the land of the first inheritance if the land is on the east. But it’s not impossible. Again, when you’re talking about geography or a lot of scriptural things that aren’t clear, I think it’s important to keep three things in mind. There are absolute truths at the top of the pyramid, there are probable truths and then there are possible truths. If it’s not an absolute truth, and that list is pretty small, then be careful you don’t promote a possible truth into an absolute truth or into a probable truth. Now sometimes there are, this one’s more probable than others, but there are still those other possibilities that could exist as revelation comes.

Thank you.