August 4, 2016

[Download PowerPoint presentation (pdf)]

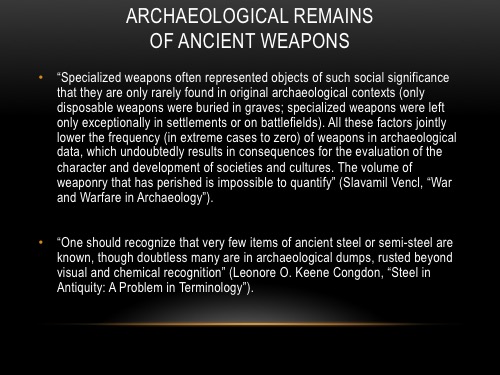

In his account of the opening salvos of a lengthy, bloody, and costly war, the paramount warrior-prophet-historian of the Nephites wrote, “And the work of death commenced on both sides, but it was more dreadful on the part of the Lamanites, for their nakedness was exposed to the heavy blows of the Nephites with their swords and the cimeters, which brought death at almost every stroke” (Alma 43:37). Swords and cimeters were only a part of the arsenal of weaponry used by peoples of the Book of Mormon, but they were a significant one. Today I am going to talk about swords and cimeters in the Book of Mormon in light of what we can learn from Mesoamerican history, art and archaeology. First I will discuss steel swords in the Book of Mormon and the Ancient Near East including the swords of Laban. Second I will discuss Pre-Columbian swords and scimitars (i.e. curved swords) known from ancient Mexico and Central America showing examples from Mesoamerican art. What did they look like? How effective were they? And how do they compare with descriptions of swords in the Book of Mormon? Finally, I will discuss recently discovered evidence for these weapons during Book of Mormon times.

Swords in the ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon

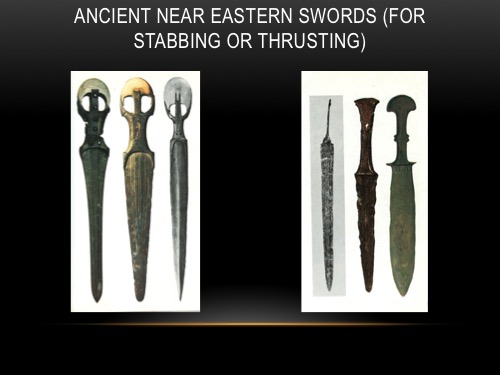

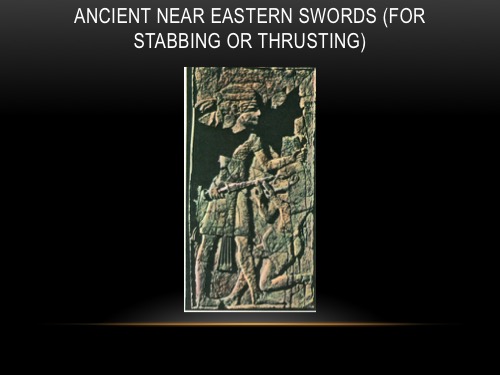

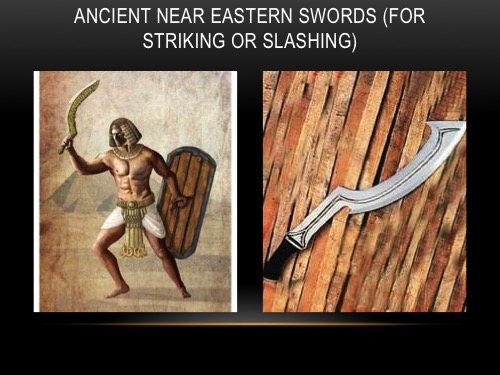

Speaking generally, in the ancient near East, there were at least two kinds of swords, one for stabbing and another for striking or slashing.

Stabbing swords, sometimes called rapiers, were pointed straight blades of various lengths and could usually do both.

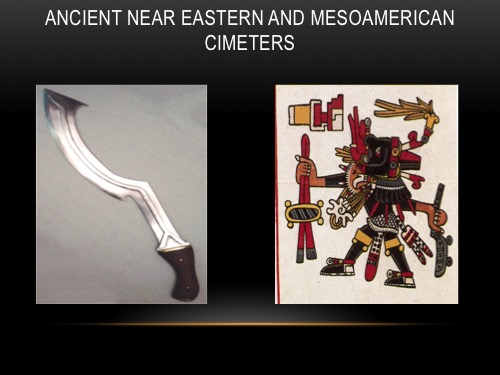

A cimeter (scimitar) is a sword with a curved blade, usually on the convex or outward curving side, although examples of double-edged blades are also known. They were primarily used to cut or slash. Previous to the development of steel technology in the ancient Near East, bronze blades were commonly used, but were not very long. After the tenth Century B.C. steel technology and the ability to make longer, durable blades, there was an eventual shift to steel blades, although surviving examples from the Iron Age are very rare.

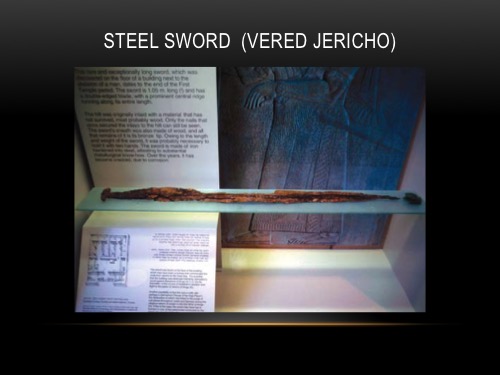

One of the earliest criticisms of the Book of Mormon was that Laban could not have had a steel sword blade, because steel was not invented until much later. The Book of Mormon, however, has since been shown to be correct in this.

About thirty years ago Israeli archaeologists discovered a meter long steel sword near the site of Jericho, dating to the time of King Josiah, Laban’s contemporary which is now on display at a museum in Jerusalem.

Were All Book of Mormon Swords Made of Steel?

What about Pre-Columbian America? Let me state from the outset that no metal sword blades of any kind have been found so far from Pre-Columbian times, including steel ones. So, as one who reads the Book of Mormon and holds that it tells of things that really happened, I want to consider why that might be the case. I want to look at what the Book of Mormon actually says and not what we have sometimes assumed it to say. I will also want to see if historical and archaeological information can help me understand the nature of these things as well.

The earliest references to steel swords in the Book of Mormon are among the Jaredites. Prince Shule who is described as “mighty in judgment . . . . came to the hill Ephraim, and he did molten out of the hill, and made swords out of steel for those whom he had drawn away with him; and after he had armed them with swords he returned to the city Nehor, and gave battle unto his brother Corihor, by which means he obtained the kingdom” (Ether 7:8-9). Note here that Shule appears to be the one with the knowledge and skill to do this. Did he pass this skill on to others? The passage does not say. It is interesting, however, that the next generation is nearly wiped out (Ether 9:12) and then there is no further mention of steel in the Book of Ether. That could be an indication that steel technology among the Jaredites was subsequently lost In periods of social anarchy, rare and valuable possessions would tend to be stolen and lost or destroyed. They couldn’t keep them (Ether 14:1; Helaman 13:34). Another passage which may indirectly refer Jaredite steel swords is where King Limhi’s search party found ruins of buildings and bones of the Jaredites along with the 24 gold plates of Ether. “And also they have brought breastplates, which are large and they are of brass and of copper, and are perfectly sound. And again they have brought swords, the hilts thereof have perished, and the blades thereof were cankered with rust” (Mosiah 8:10-11). Now we are not told if the blades were of rusted steel or some other metal such as bronze which can also corrode. In any case, these things were brought back“for a testimony that the things that they had said are true” (Mosiah 8:9). This could be an indication that by Limhi’s day swords with metal blades were unusual or rare.

After his separation from the Lamanites, Nephi states that he “did take the sword of Laban and after the manner of it did make swords, lest by any means the people who were now called Lamanites should come upon us to destroy us” (2 Nephi 5:15). What does it mean, when he says that he made swords “after the manner of the sword of Laban”? Since Laban had a steel sword that could mean that Nephi made steel bladed swords like Laban’s sword. Another possibility is that he made some swords after the general pattern of Laban’s sword, perhaps a long straight shaft with sharp blades along the edges, rather than a curved sickle sword that was bladed only on one side. Writing years later, Nephi described Laban’s blade as made of “most precious steel” (1 Nephi 4:9), suggesting that there was more than one kind and that some with which he was familiar was less “precious.” There are early Nephite references to “steel.” Nephi broke his bow of “fine steel,” and Laban steel blade was of “most precious steel.” Do these terms reflect different grades of technological skill? It’s possible that Nephi and some early Nephites were able to make other steel swords, but it is also possible that while they were able to work carburized iron (steel) for ornamentation purposes, they were unable to master other steeling techniques, such as tempering, needed to make long effective steel blades.

But lets assume for now that Nephi made some steel swords. How many did he make? Nephi’s people at this early time could not have been numerous. And after the death of Nephi, how many people possessed his steel technology? Did all Nephites know how to work steel or just some? As with many other cultures, relevant metallurgical knowledge may have been restricted to a few individuals or artisans and could have been lost in just one Lamanite raid (Note Omni 1:5-7). The last reference to steel among the Nephite is during the time of Jacob’s grandson Jarom (Jarom 1:8), and is never again mentioned again among the Nephites. When the Zeniffites return to the land of Nephi a few generations after this, they know about iron and other metals, but not steel. This incidentally is also the last reference to Nephite “iron” (Mosiah 11:3, 8). It was apparently an exceptional thing for Nephi or King Benjamin to wield the sword of Laban in the defense of their people (Jacob 1:10; Words of Mormon 1:14). That again, suggests to me that steel swords were the exception not the norm and that among the people of the Book of Mormon metal sword blades were rare elite items, the exception rather than the norm and would tend to be carefully preserved. Other kinds of swords would have been adequate to their needs.

Mesoamerican Wood bladed swords

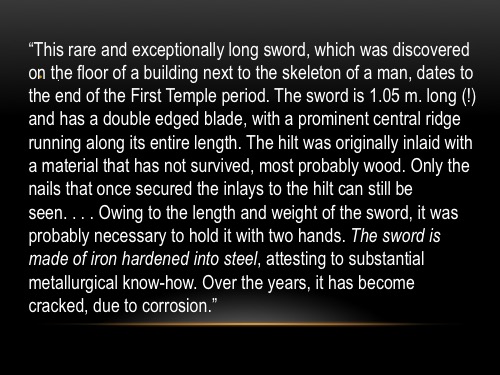

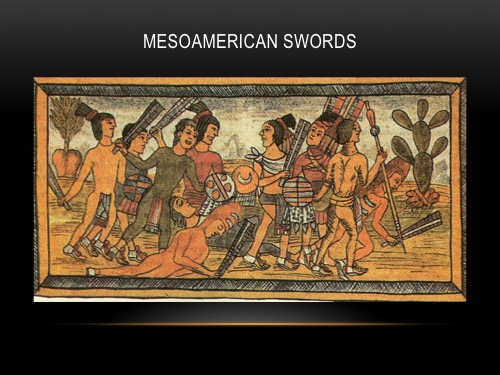

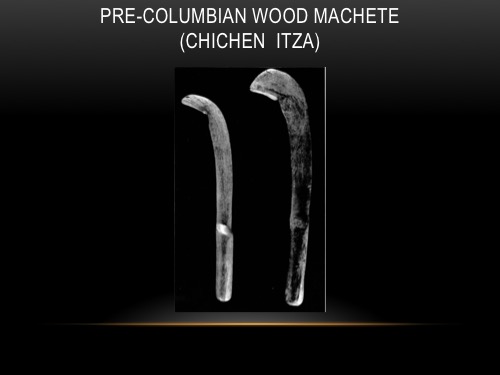

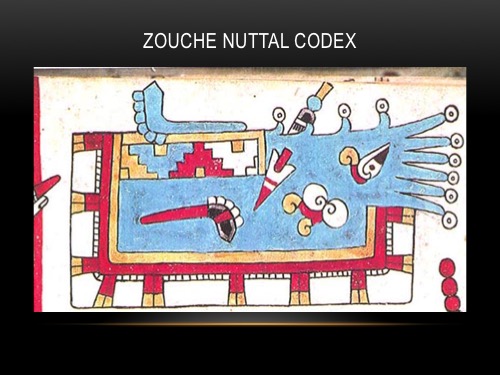

Historical accounts, Mesoamerican art, and anthropological sources show that there were a variety of sword and sword-like weapons in Pre-Columbian times. These include sharp wood-bladed swords of hardwood said to be tough like bone, one and two-handed swords with blades of obsidian, flint, and sometimes even shark teeth, and a cutlass or curved weapon with obsidian or flint blades. Swords with sharp hardwood blades were known throughout North and South America in Pre-Columbian times, including Mesoamerica. In fact, today’s steel-bladed machete is believed by some anthropologists to be the functional equivalent of a certain agricultural tool from pre-Columbian times.

Hayden has suggested that in highland Guatemala, “A sharp-bladed, heavy piece of hardwood may have been employed [anciently] for cutting down or ringing scrub and secondary growth, which is today cleared with a machete. People in that region before World War II, when metal implements were scarce and expensive, used tools called palo machetes (“wooden machetes”) to clear scrub growth from fields. These were made of hardwoods like madron.”

Clemency C. Coggins, a specialist in the Maya civilization, believes the modern machete “to be a direct descendant of the wooden sickle-like tools found [preserved] in the Cenote” or well at Chichen Itza. Hayden observes that “such a tool might also serve for defense against predators, snakes, and strangers while in the field”; consequently, “the agricultural tool and the weapon may have been one item.”

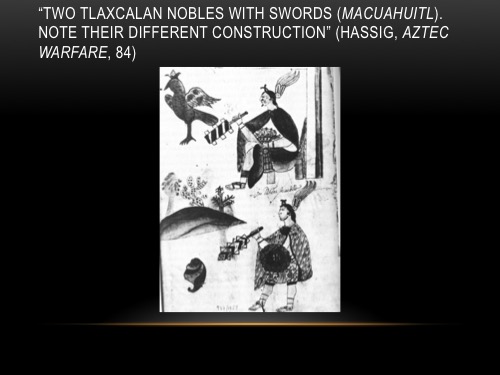

macuahuitl. Brian Hayden suggests that in some cases “obsidian-edged macanas were used predominantly by the elite knights, and the plain wood blades were used by peasant fighters.”

Sometime around 200 BC, Zeniff recorded that his people were attacked by the Lamanites while they were “feeding their flocks, and tilling their lands” (Mosiah 9:14). When the survivors fled to the king, he had to arm them quickly. Thus “I did arm them with bows, and with arrows, with swords, and with cimeters, and with clubs, and with slings, and with all manner of weapons which we could invent” (Mosiah 9:16). Nothing is said of what materials were used to make these arms, but given the emergency situation it is plausible that they used or based them upon tools that they already employed for everyday purposes, such as wooden implements for clearing vegetation and slings and the bow and arrow for hunting. Since the Lamanites were without armor at this time, even such relatively crude weapons could have been effective.

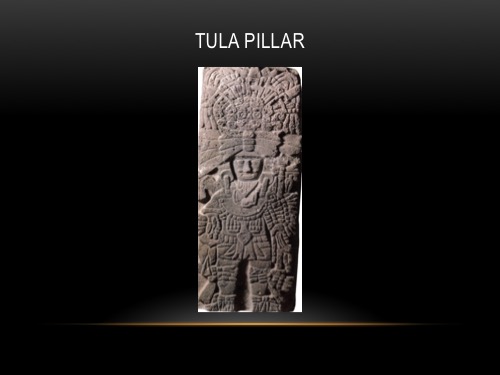

The Macana or Macuahuitl Sword

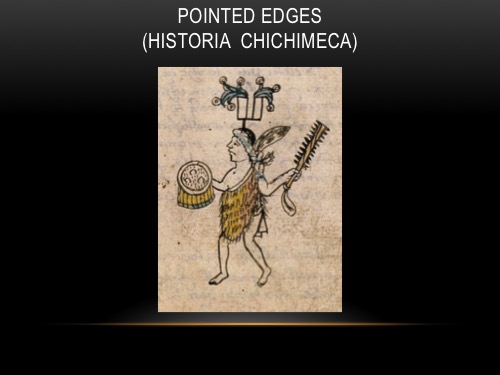

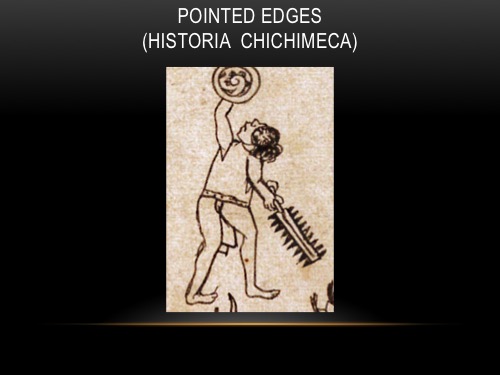

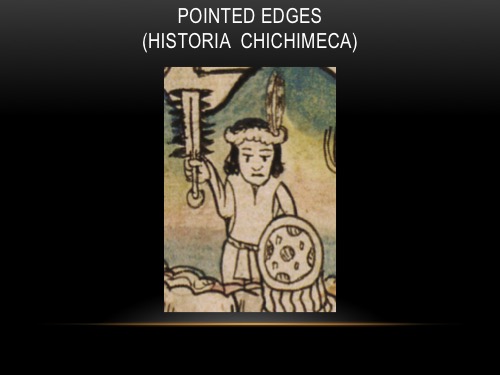

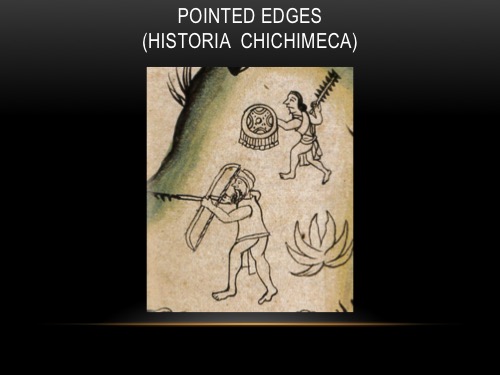

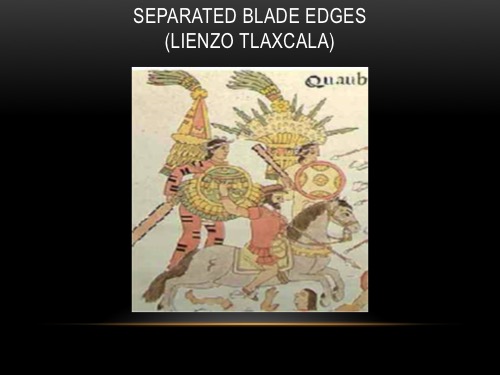

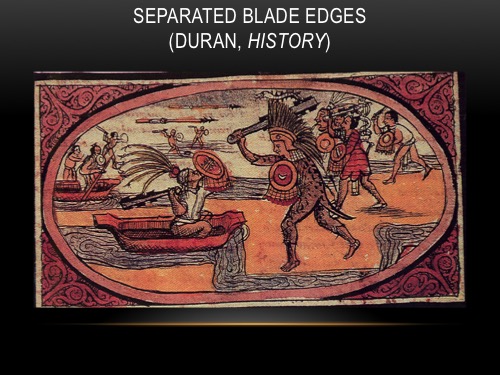

The best known Mesoamerican sword was the deadly weapon called by the Aztec a macuahuitl. This weapon consisted of a long, flat piece of hardwood with grooves along the side into which were set and glued sharp fragments of obsidian or flint. Several inches of the wood-piece were usually left as a handgrip at the bottom, and rest of the instrument having a sharp bladed edges along the sides. Martial art suggest a variety of blade forms, including staggered blades, pointed, and continuous. Sources also indicate that these swords varied in length, anywhere from 50 cm. (19.7 inches long to five feet in length. The longer and heavier weapon had to be wielded both two hands. According to one Spanish source, the Aztec “broadswords” had “their hilts . . . not quite so long” as those of Spanish swords and “three fingers wide.” Hassig notes, “Some swords had thongs through which the user could put his hand to secure the weapon in battle” as he grasped the hilt. Martial art frequently show the hilt of this weapon with a knob at the end which would obviously help keep the heavy weapon from slipping out of the user’s hand during combat.

Many years ago I wrote an article citing historical sources, mostly first-hand sources, describing these Aztec weapons as swords. Those who encountered the deadly effects of this weapon clearly considered it such. Additionally, most historians of Mesoamerican warfare consider it a sword. Some writers have spoken of this weapon as a war club, but the term club is not apt. The weapon spoken of was designed to slash, rather than to crush, as a club would. In fact eyewitness accounts not only describe it as a sword but distinguish it from clubs. The Aztec word applied to this weapon was macuahuitl. Another word sometimes used by historians was a Carribean Taino word macana. The Maya had their own word for this weapon–hadsab “that with which one strikes a blow.” It is interesting to compare this to the Hebrew word for “cut” hsb used in Isaiah 51:9 where the prophet speaks of the Lord cutting the cosmic enemy.* Some historians have occasionally applied terms such as macana and macuahuitl to other obsidian-bladed weapons that would not qualify as swords. This means that one has to be careful not to assume that all references to macuahuitl or macana refer to swords. It is clear, however, that many of them were swords and that they have a long history in Mesoamerican warfare. In most cases, when I identify weapons in art as swords, I will only do so because other scholars have done so.

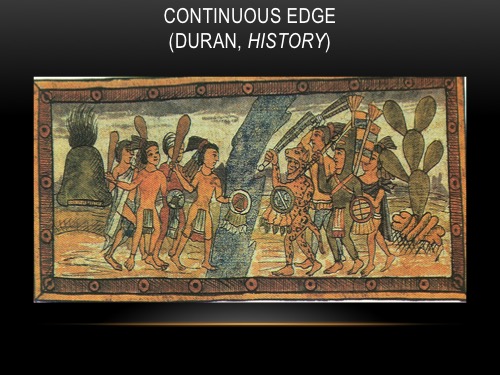

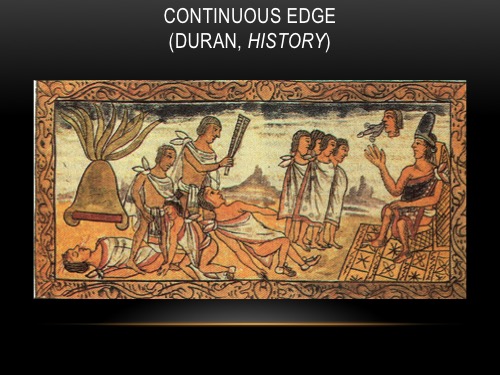

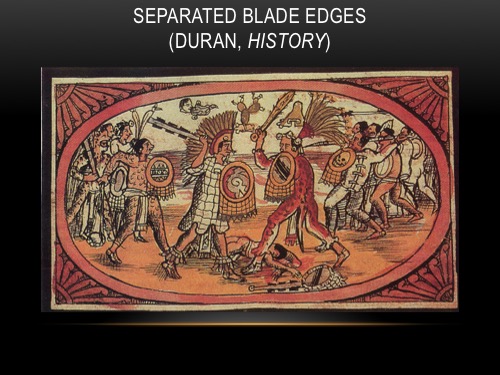

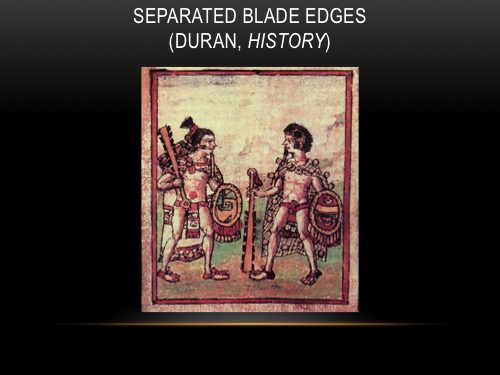

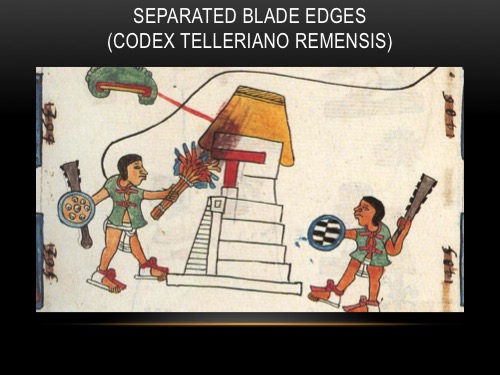

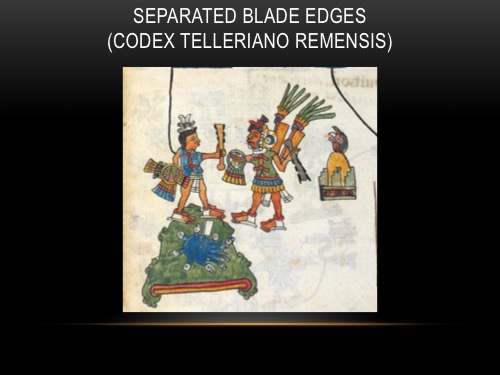

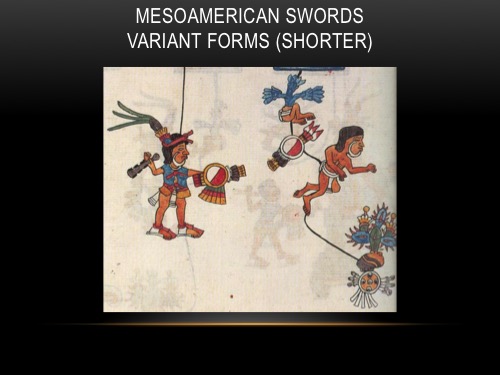

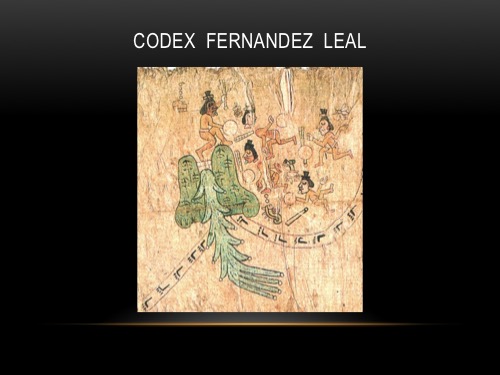

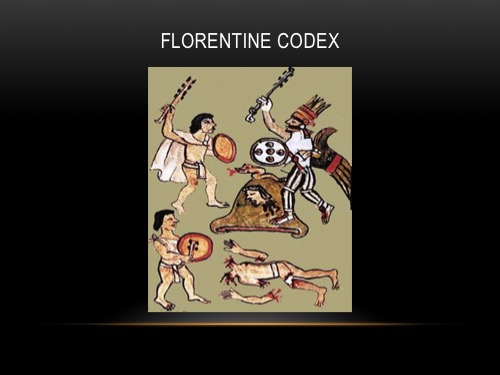

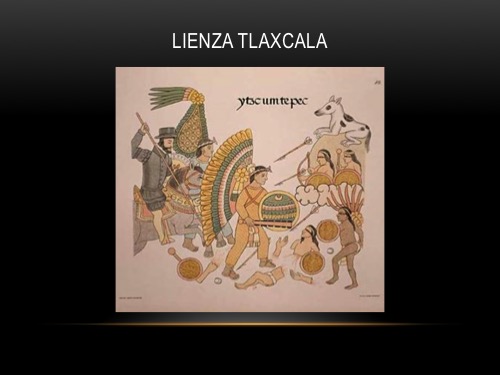

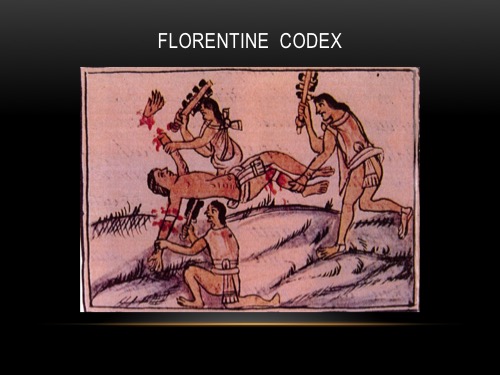

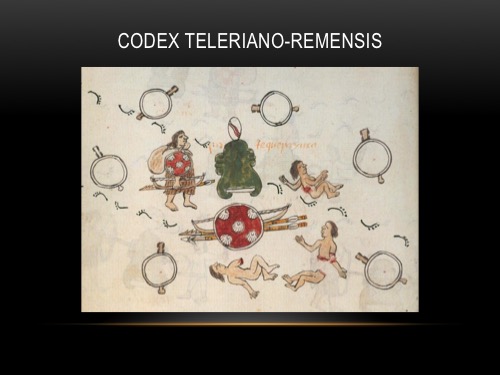

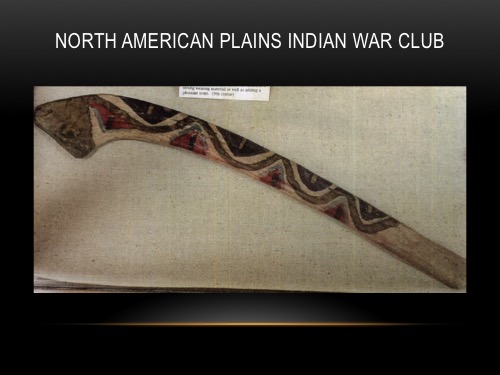

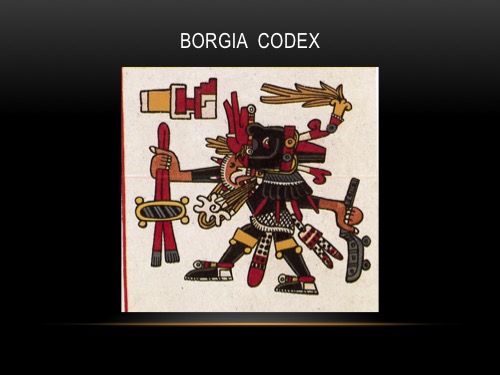

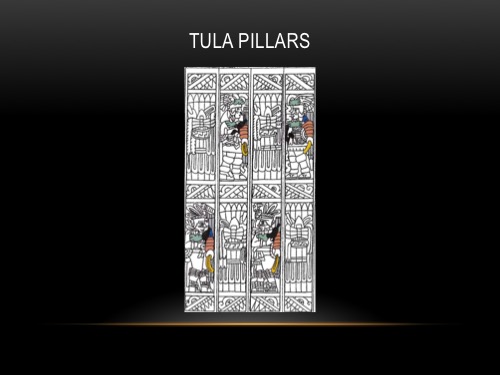

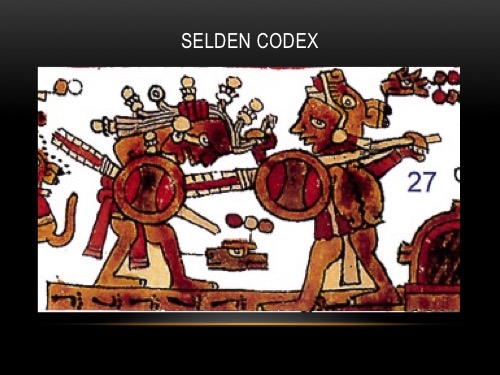

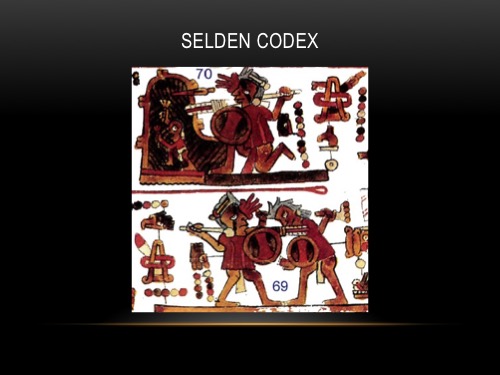

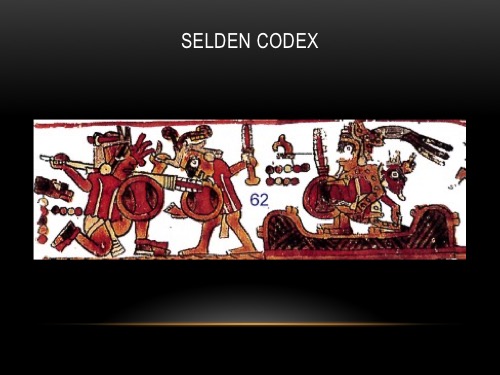

What did Mesoamerican Swords Look Like? Here are some example from Mesoamerican Art.

How Sharp Was the Macuahuitl Sword?

Obsidian blades weapons like the aztec macuahuitl were very sharp. One common claim of Spanish histories is that an Aztec sword could cut off the head of a horse with one blow. Most of these accounts, however, are not from first-hand sources. First hand accounts do relate several times when horses were easily killed with such weapons. Here are a few examples.

As the Spaniards tried to capture one of them to find out where they were from, the Indians with two blows of their swords killed two horses, and also wounded two Spaniards, and so defended themselves that not one of them was taken alive.

Two Indians were waiting for the horsemen on the side of the road. One Indian at a single stroke cut open the whole neck of Cristóóbal de Olid’s horse, killing the horse. The Indian on the other side slashed at the second horseman and the blow cut through the horse’s pastern, whereupon this horse also fell dead.

One Indian I saw in combat with a mounted horseman struck the horse in the chest, cutting through to the inside and killing the horse on the spot. On the same day I saw another Indian give a horse a sword thrust in the neck that laid the horse dead at his feet.

Clearly, Mesoamerican swords could have devastating effect upon the Spanish horses, if their opponents could get close enough to strike, but no extant account actually says that the head of any horse was entirely cut off with one blow. The closest to this comes from Bernal Diaz who actually witnessed one encounter.

While we were at grips with this great army and their dreadful broadswords, many of the most powerful among the enemy seem to have decided to capture a horse. They began with a furious attack, and laid hands on a good mare well trained both for sport and battle. Her rider, Pedro de Moron, was a fine horseman . . . . [they] seized his lance so that he could not use it, and others slashed at him with their broadswords, wounding him severely. Then they slashed at his mare, cutting her head at the neck so that it hung by the skin. The mare fell dead.

The account suggests that Moron’s horse may have been struck with more than one blow. It is also possible that the weapon involved may have been the heavier and much longer two-handed weapon, rather than the shorter sword, and that the blow was probably a heavy downward stroke.

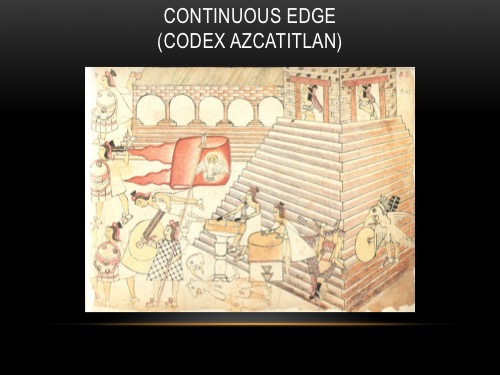

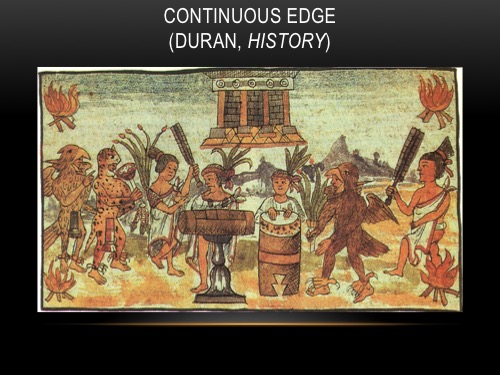

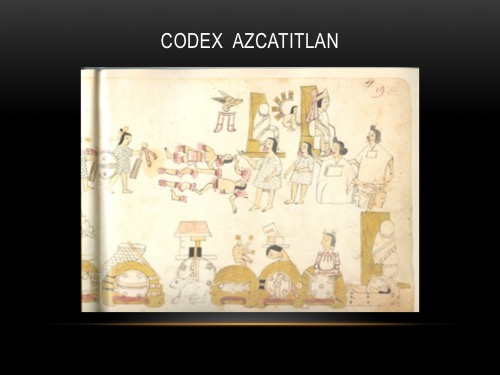

Book of Mormon swords were obviously very sharp. Abundant evidence from Mesoamerican art and historical sources attests to the deadly effectiveness of these swords against human opponents. Pohl observes, “The brutal nature of this weapon made combat bloody and dismemberment common.” Spaniards who faced native Mesoamerican swords in battle were deeply impressed by their deadly cutting power and razor-like sharpness. Following the conquest of the city of Azcapotzalco by the Aztecs, the neighboring ruler of Coyoacan tried to persuade them to rebel again their new overlords. In response, the recently defeated ruler dismissed the idea as extreme folly. “Are we to see the streets of our city again bathed in blood, covered with entrails, with arms and heads and severed legs?” In a subsequent notorious event, an Aztec messenger was killed after delivering a formal declaration of war to the ruler of Tlatlelolco. “While he yet spoke, Teconal appeared, sword in hand, and with one blow cut off Cueyatzin’s head. This head was then carried to the boundaries of Tenochtitlan, where it was thrown. After that the Tlatelolcas set up a great howling, calling out Tlatleloloco! Tlatelolco!” The Codex Azcatitlan portrays the gruesome aftermath of the conflict that subsequently ensued. Here we see the dismembered and decapitated remains of some of the dead. Note the variant forms of swords.

Other codices also portray the deadly nature of macuahuitl sword blades.

One area that has been little explored is the examination of extant human remains from conflict and warfare.

What you see here are some human bones from an Aztec site which one recent scholar believes to have been severed by a cutting instrument, possibly a macuahuitl [slide]. Modern experiments on animal carcasses (none have been done of human remains for obvious legal and ethical reasons), suggest that there would have been considerable chipping of the blades in the course of battle, so we should, “consider the damage that would be done when even one of the blades impacted on a limb and cut through to the bone, embedding micro-flakes of obsidian, prohibiting healing and causing infection.”

While obsidian sword blades were deadly and effective, they could also be fragile, “Consequently,” as Ross Hassig explains, “warriors probably made some effort to avoid direct blows to the blades; they may have used the flat of the weapon to parry and have struck with the bladed edges. But they were more likely to have deflected blows with the shield because parrying damaged their weapon and meant losing the initiative and the opportunity to strike back. Thus, macuahuitl duels are unlikely to have resembled European saber duels in which combatants struck and parried with the same weapon” In the course of battle the blades would chip and break and need to be replaced. “Stone blades shatter when they strike other weapons, but they usually do not when they strike cotton armor, flesh, or shields. Nevertheless, the breakage during combat must have been significant. While weapons with shattered blades can still be used effectively as clubs, their effectiveness is impaired. This the periodic withdrawal of troops during combat served not only to rest the men but also to allow them to trade weapons. Overnight or after battles, blades were probably replaced, and other arms were repaired.”

Historical sources suggests that macuahuitl swords could vary in quality as well as form. One some sources indicate that the Aztec blades would begin to chip and break after only a few blows, eyewitnesses affirm that “the blades were so set that one could neither break them nor pull them out.”

Stained Swords Made “Bright”: A Metaphor of Divine Redemption

The Lamanite king named Anti-Nephi-Lehi admonished his fellow converts.

And I also thank my God, yea my great God, that he hath granted unto us that we might repent of these things, and also that he hath forgiven us of those our many sins and murders which we have committed, and taken away the guilt from our hearts, through the merits of his Son.

And now, behold my brethren, since it has been all we could do (as we were the most lost of mankind) to repent of all our sins . . . And to get God to take them away from our hearts, for it was all we could do to repent sufficiently before God that he would take away our stain.

Now . . . Since God hath taken away our stains, and our swords have become bright, then let us stain our swords no more with the blood of our brethren. . . . Let us retain our swords that they be not stained with the blood of our brethren; for perhaps, if we should stain our swords again they can no more be washed bright through the blood of the Son of our great God, which shall be shed for the atonement of our sins . . .

Oh, how merciful is our God! And now behold, since it has been as much as we could do to get our stains taken away from us, and our swords made bright, let us hide them away that they may be kept bright, as a testimony to our God at the last day, or at the day that we shall be brought to stand before him to be judged, that we have not stained our swords in the blood of our brethren since he imparted his word unto us and has made us clean thereby.

And now, my brethren, if our brethren seek to destroy us, behold we will hide away our swords, yea, even we will bury them deep in the earth, that they may be kept bright, as a testimony that we have never used them, at the last day (Alma 24:10-16).

Now a steel blade can be easily wiped off after battle, but a macuahuitl sword becomes stained as the blood, shed during combat, seeps into the wooden base. Following battle, the soldier warrior would replace the chipped and damaged obsidian blades with new ones, but the hard wooden piece into which they were set, lasts much longer and would be used again and again, each time soaking up blood, unless it became broken and also needed replacement.Now put yourself in ancient America where these things were used. How do you remove blood from a blood-soaked wooden weapon? You can’t. Sword stained with blood mirror human hearts and consciences stained with sin and guilt. So we have a powerful metaphor emphasizing the profound power, and mercy of God in taking away the stains of sin and guilt through his own atoning blood. What about the idea of brightness? Many types of obsidian have a fine luster so that the edges of a macuahuitl swords, when reflected upon by sunlight, might well be described as bright. Having learned of the Gospel of Christ, and having believed it, these converts repented of all their sins and are made clean. Freed from guilt and shame they obtained a hope as bright as the light which once reflected upon their obsidian blades. So, while the metaphor is understandable with steel blades, it would have been especially meaningful and profound, perhaps more so in a cultural context of Mesoamerican warfare and weapons.

Why have so few archaeological examples of Mesoamerican swords survived?

Now sometimes people ask, well why don’t we find any Nephite swords? There were probably (this is a conservative estimate) tens of thousands of these swords just in Aztec time, a very late period in Pre-Columbian history. How may examples of Aztec swords have survived until today? I only know of one published example and it’s a definite “maybe” because only the obsidian remains. Note what several authorities on ancient warfare have to say:

When you consider how many of these weapons once existed in Aztec times, this is really quite remarkable–and that is just a few hundred years ago. When we are taking about the Nephites, Lamanites, and Jaredites we are talking about several thousand years ago. Now there are some reasons for that which those scholars mention. In the case of sword blades, once they chipped and were broken, they were often reused as projectile points, so they would lose their original shape as sword blades.

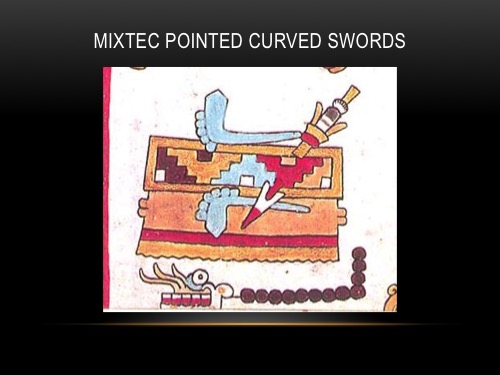

Were there Mesoamerican Scimitars?

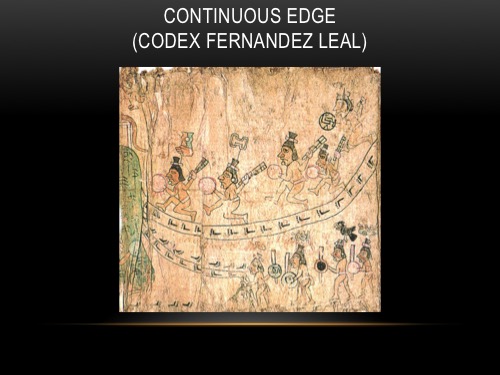

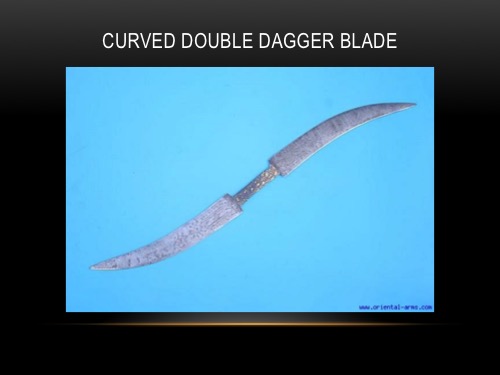

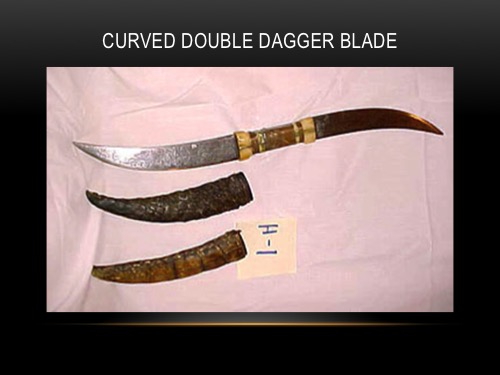

Ross Hassig has identified a curved weapon portrayed in Postclassic Mesoamerican art which he calls a “short sword.” Some recent scholars describe this weapon as a curved macuahuiltl. It was designed for slashing and consisted of a flat hard wooden base approximately 50 cm. (20 inches) long into which were set obsidian blades along both edges. “It was an excellent slasher and yet the forward curve of the sword retained some aspects of a crusher when used curved end forward.” The lightness of the short sword enabled the soldier to carry more than one weapon. “Soldiers could now provide their own covering fire with atlatls while advancing and still engage in hand-to-hand combat with short swords once their closed with the enemy.”

This weapon or something very similar may have been used until shortly before the arrival of the Spanish in some sectors of Mesoamerica. Huastec engravings on shell show “a sort of curved club, apparently of wood and with a cutting edge” which may have been a similar weapon. Hassig reported that short swords are portrayed in the hands of warriors on a Aztec monument from the ceremonial center at Tenochtitlan and took this as evidence that the weapon was either “still in use or at least remembered as a functional weapon” at that time. Reportedly among the weapons used by the ancestors of Guatemalan peoples were “certain cutlasses they say were made of flint.” Another tradition relates that the Pre-Columbian ancestral heroes of certain some Mexican tribes taught their people to make fire and “gave them also machetes or cutlasses of iron.” Interestingly, if credited, this may suggest that pieces of iron may have sometimes been used as sword blades rather than obsidian. In any case, this weapon seems to be a reasonable candidate for the Book of Mormon scimitar.

Why would a warrior have both a cimeter and a sword?

When the Zoramite leader surrenders his weapons to Moroni, he delivers up his bow, his sword and his cimeter (Alma 48:8). Some writers have thought it odd that the dissident would have two different swords. In the biblical account of David’s confrontation with Goliath the Philistine champion is said to be well armored. In addition to his spear he had both a hereb sword with a sheath (1 Samuel 17:51) and a kidon which he carries between his shoulders (1 Samuel 17:6). The term kidon was once a mystery, but texts from the Dead Sea Scrolls suggest that the kidon was some kind of sword and is now widely acknowledged to have been a scimitar. When challenged David responds to his opponent, “You come against me with a sword and spear and scimitar, but I come against you with the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel whom you have defied!” (1 Samuel 17:45). Both weapons need not have been carried or wielded simultaneously. As with Goliath, one or more of the weapons Zerahemnah turns over to Moroni may have been carried into battle by a guard or servant during battle. Hassig notes that the short curved sword was lighter. It may be useful to have a secondary and lighter blade, after the macana sword blades became chipped or worn down during the course of battle.

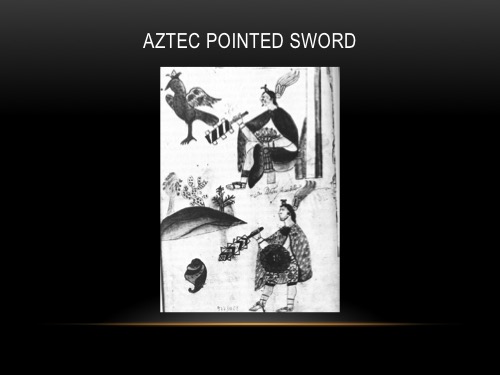

Could could any Mesoamerican swords have been used to “pierce” an enemy?

During one battle, unarmored Lamanites, “were exposed to the sharp swords of the Nephites; yea, behold they were pierced and smitten” (Alma 44:18). One Nephite soldier, “took up the scalp” of one Zarahemnah, “and laid it upon the point of his sword” (Alma 44:13). These passages suggest that some Nephite swords were had the ability to pierce and that some were pointed. Most passages, however, speak of using swords to cut. The dissenter Coriantumr attempts to “cut his way through with the sword” (Helaman 1:23; see also Alma 52:34; Helaman 1:23-24). By far the most common verb is “smite” or its derivatives. Some of these also refer to cutting as when Ammon “smote off” the arms of his enemies “with the edge of his sword” (Alma 17:37), and the Lamanites, during one particularly fierce encounter “did smite off” many of the arms of the Nephites (Alma 43:44). Coriantumer “smote off the head of Shiz” (Ether 15:30-31). Given the frequency of these textual references, we could conclude that, while some Book of Mormon swords were pointed, most may not have been, but were more often used to slash or cut. This, incidentally, agrees with Pre-exilic Israelite experience. Biblical scholar T. R. Hobbs concluded, based upon textual references, that, “the Israelites favored the slashing sword, designed with one or two edges” and that “few rapiers (thrusting swords) have been discovered from the Iron Age in Israel, whereas many more slashing swords (cutlasses) or various kinds have been found.”

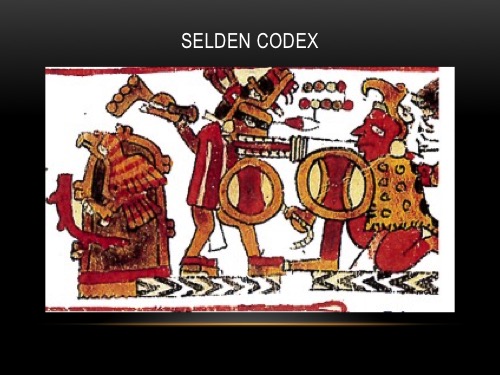

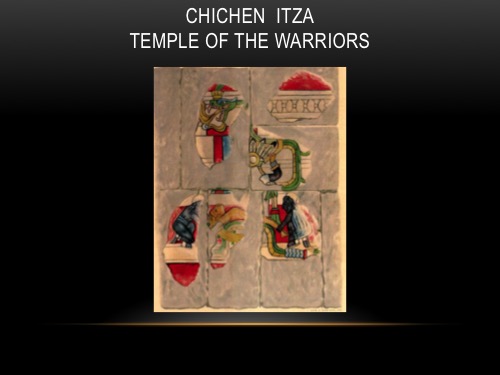

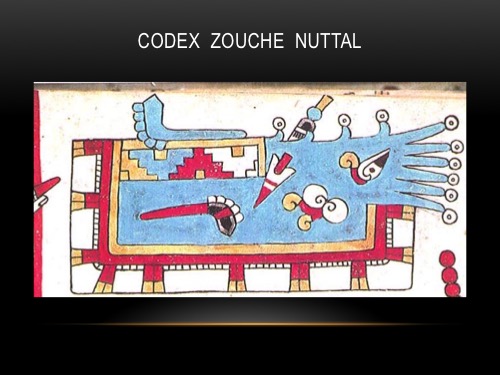

Mixtec codices show two similar obsidian bladed weapons wielded by warriors which scholars consider to have been macanas. One of these has a long pole like handle and resembles a spear or a lance.

Representations show that it was used to stab or pierce, even though it is not shown with a pointed tip. A similar weapon is also shown which has a much shorter handle and is likely a sword.

The bladed portion of the shorter weapon exactly resembles the longer spear which was used to pierce and stab. This suggests that the sword represented could likewise be used to pierce an opponent when needed. Murals from the Temple of the Warriors at Chichen Itza show that these could sometimes be wielded with the sharpened end forward, for example when piercing the chest of the sacrificial victim during human sacrifice.

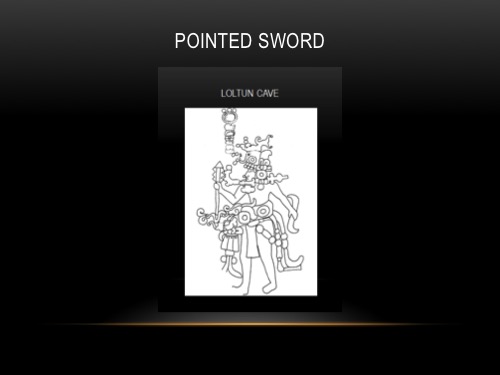

Here is a pointed Aztec weapon which Hassig considered a sword.

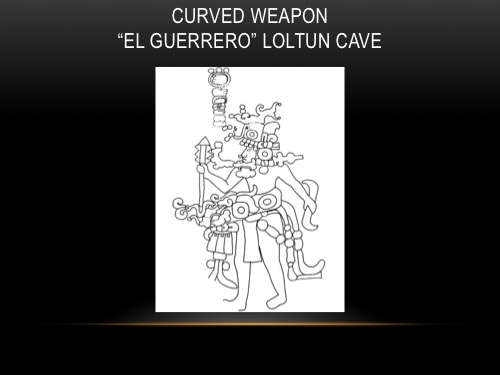

The warrior portrayed in the carving at Loltun Cave holds a similarly pointed weapon inset with obsidian blades which some scholars have identified as a Mesoamerican sword.

Others have suggested that weapon in question was actually a mace or a club. Whether a sword, a mace or a club, it is clear that weapons of this general class could indeed be pointed. Here are a few others.

All of which suggests that while Mesoamerican swords need not have been pointed, some had sharpened wooden tips or were tipped with obsidian or flint.

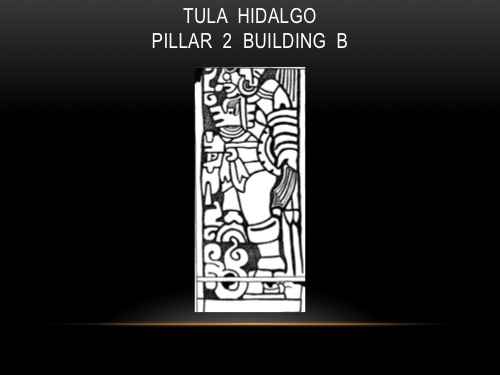

Were there Swords and Cimeters During the Classic Period?

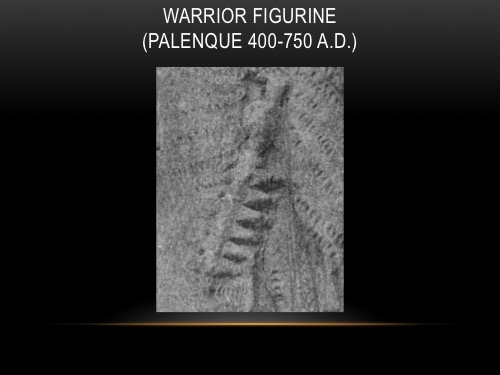

Ross Hassig, an excellent authority on Pre-Columbian warfare suggests that the macuahuitl, which he terms a broadsword, appeared only after the 13th century. Some critics of the Book of Mormon have also questioned whether such a weapon was present in Book of Mormon times, asserting that earlier versions of these weapons were simply barbed clubs. There are good reasons, however, to question that assumption. Mesoamerican art dating to the Classic period show that swords had a much longer history. A figurine from Palenque, Mexico, shows a warrior bearing such a macuahuitl sword.

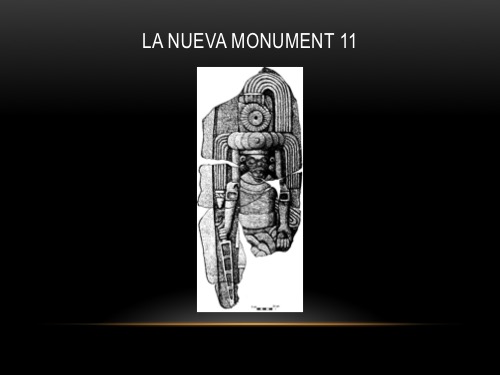

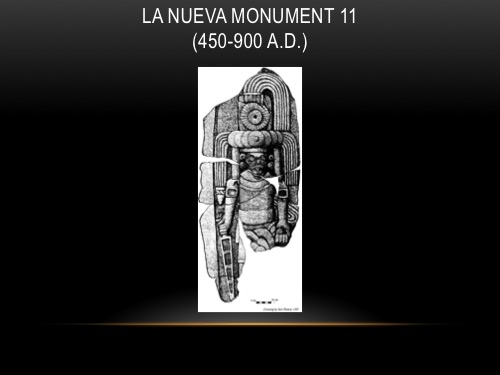

As noted already Monument 11 on the Pacific coast of Guatemala, appears to portray a ruler posing with such a weapon.

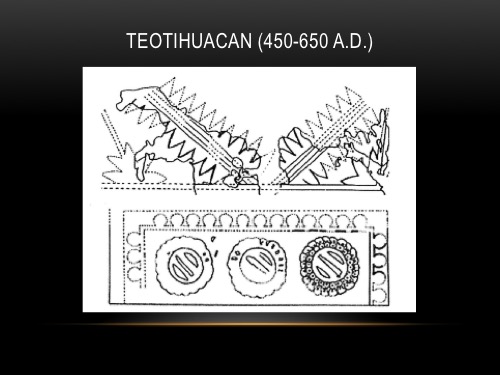

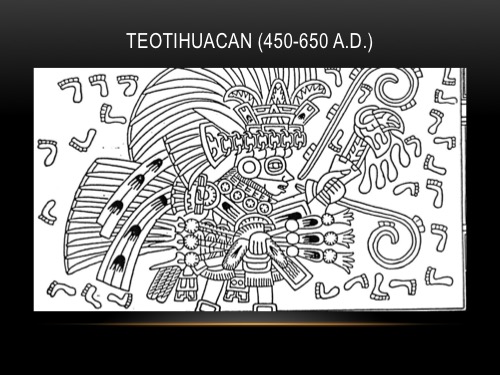

Scholars working at the site of Teotihuacan in Zone 11 (known as El Gran Conjunto) believe they have identified several weapons on the damaged murals at that site. Mural 1 in Portico 3 shows two weapons with sharp saw-like edges of triangular blades, directly above two rounded shields, leading Ruben Cabrera to conclude that “these figures represent two macanas or military weapons.” More recently, another specialist agreed that the object represented “weapons that have cutting blades of wooden swords similar to the macuahuitl,” something that should not really be surprising since the Teotihuacanos were experts in the use of obsidian.

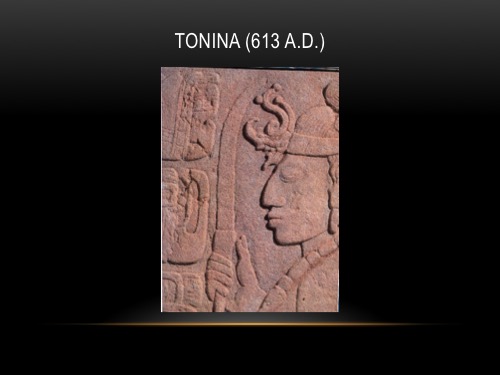

Curved Scimitar-like weapons are also shown in Classic Mesoamerican art. A monument from Tonina, Mexico, which dates to 613 A.D., shows a noble posing with a curved “scimitar-like flint blade.”

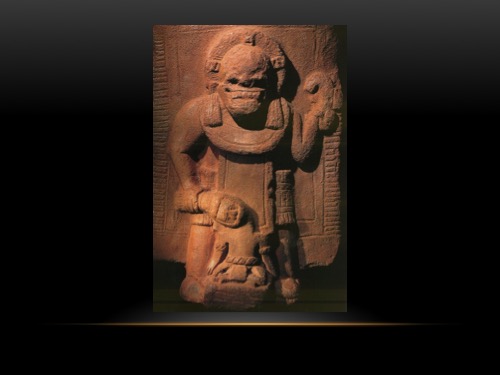

A figurine found today in the Museo Regional de Campeche, which is probably from this same period, portrays a warrior with a death mask who grasps an unhappy captive in his right hand and a curved weapon in his raised left hand with which he is about to decapitate his victim. The weapon in the figure’s left hand has been called an ax by some, but given its curved form could appropriately be called a scimitar.

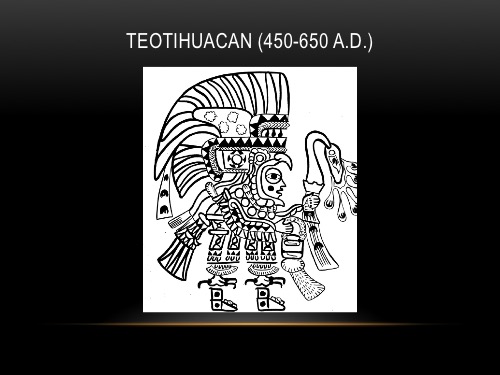

Again at Teotihuacan, murals portray warriors with long curved blades upon which are impaled human hearts. All of these example show that swords and scimitars are various forms were known much earlier than has been generally thought.

But is there earlier evidence that dates to the time of the Book of Mormon?

Here again we see the warrior portrayed at Loltun Cave who holds two weapons.

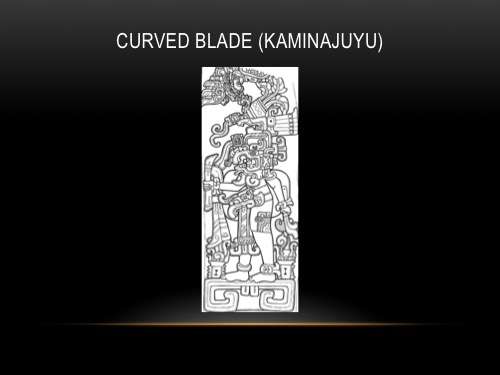

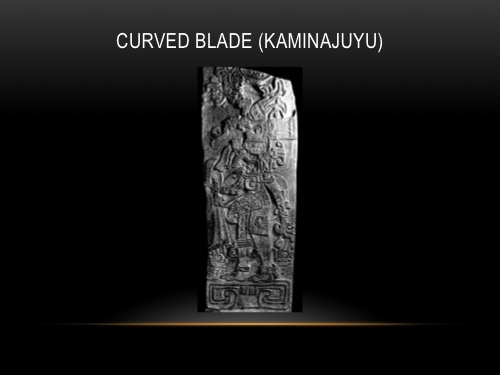

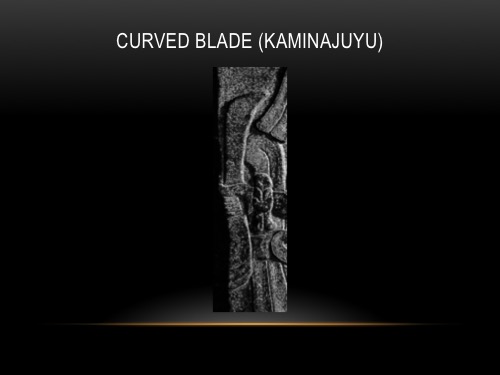

The one in his right hand may be a club, but bears a close resemblance to later representations of a macuahuitl sword. In the left hand is a snake like object which is also thought to be a weapon, which some have compared to the object held in the right hand of the figure shown on Stela 11 at Kaminaljuyu.

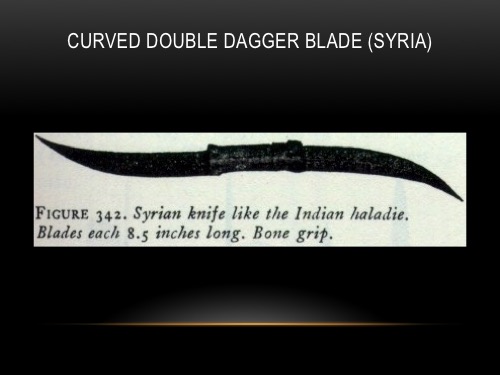

This figure holds what a appears to be a double-curves blade which bears a resemblance to a double-dagger or haladie known from ancient Syria and India.

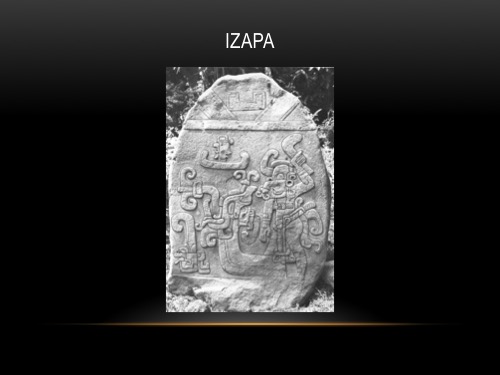

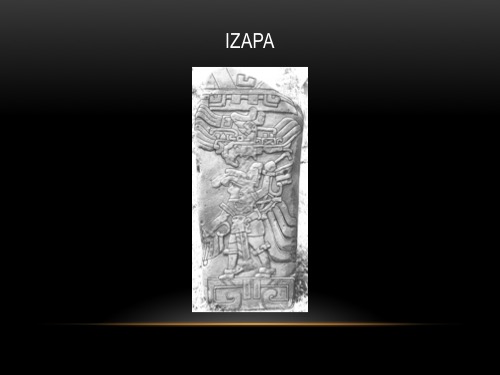

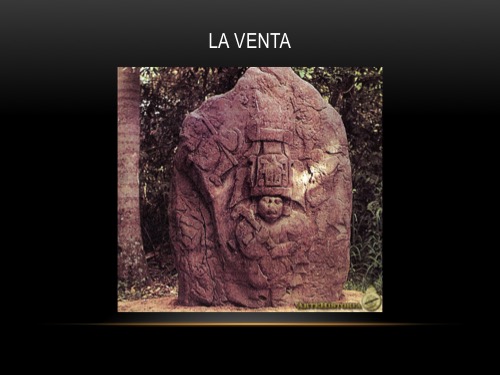

Other curved object objects, thought by some to be curved blades are found on Pre-Classic monuments at Izapa and La Venta. All of these date to the preclassic.

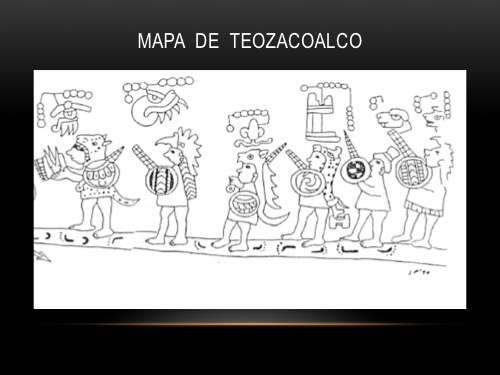

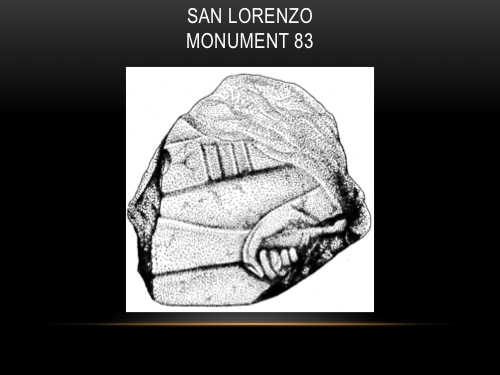

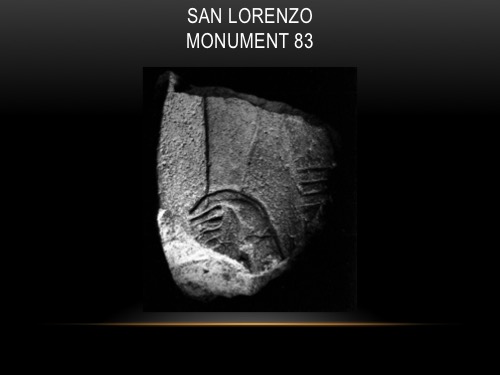

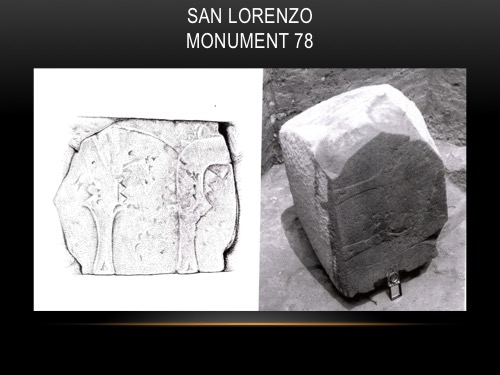

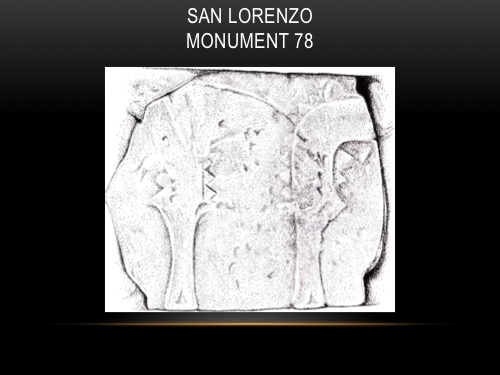

Most recently, examples of Mesoamerican swords have been discovered at the early Pre-Classic Olmec site of San Lorenzo in Southern Veracruz (1500-900 B.C.).

Archaeologist Ann Cyphers, the leading archaeologist at the site, notes that monument 78 shows a “macana” that “has a curved body with eleven triangular element encrusted in the sides.”

On the same monument, another object, which she also identifies as a macana has a handle with a straight base inset with triangular blades on both edges. She notes, “its form is like that from later times particularly the Mexica [Aztec] culture.” San Lorenzo Monument 91 also displays, “an object in the form of a curved macana with 14 triangular points” including one on its tip. By its design, clearly this is the same form of curved weapon found in later postclassic art–Hassig’s curved “short sword.” These example suggest that swords and scimitars were not a late innovation in Mesoamerican arms, but were known from preclassic times, just as the text of the Book of Mormon suggests.