Audio and Video Recording Copyright © 2016 The Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research, Inc. Any reproduction or transcription of this material without prior express written permission is prohibited.

Scott Gordon: Royal Skousen is a professor of linguistics and English language at Brigham Young University, and the editor of the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, and Stan Carmack is an independent linguistics scholar with a doctorate in Hispanic languages and literature from the University of California at Santa Barbara. And these two have made a very good team in studying the Book of Mormon. And so with that very short introduction, here is Royal Skousen.

Royal Skousen: So we are going to be talking about finishing up the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project today. And basically what we are going to be dealing with is the last printed volume of The Critical Text, Volume III: The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon.[1]

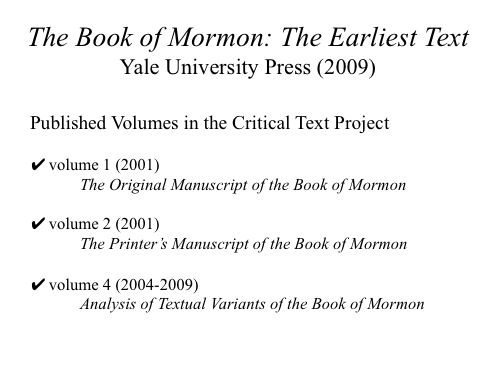

The main publishing event of The Critical Text Project has been the Yale edition of the Book of Mormon, published in 2009.[2] There are three volumes that have been published. Volume I[3] and II[4] are the transcripts of the manuscripts of the Book of Mormon. They will eventually be redone with photographs by The Joseph Smith Papers. In fact, the second one, Volume II, The Printer’s Manuscript, was done last August by The Joseph Smith Papers,[5] the transcript with the photographs, all the pages. Volume IV is Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon[6] and this goes through the whole text, arguing for what it originally read like.

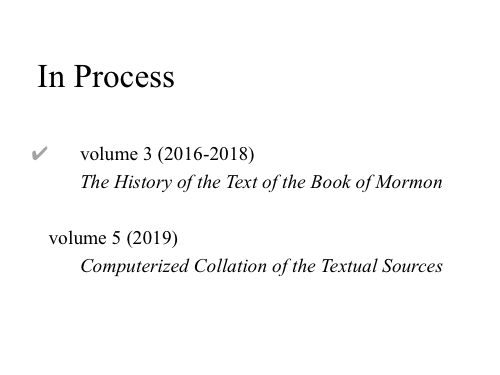

So in process is Volume III, which will be appearing in six parts in the next three years, and it is called The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon.

At the conclusion of the printed volumes we will produce the computerized collation of all the textual sources, and this will be available so people can search for any variant in the text and how it has changed throughout the history.[7]

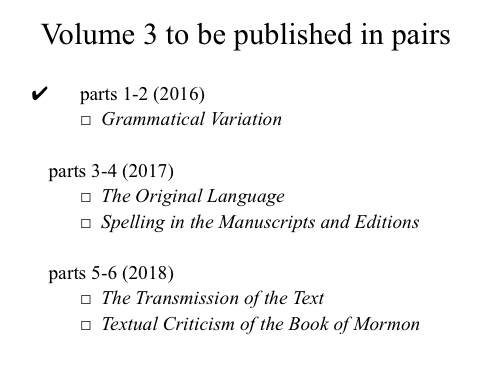

So there are six books that are going to be … six parts in Volume III. The first two parts are called Grammatical Variation and they were published last April. I will show you them here. [Holds up volume.] This is one. There is a second one like it, 1300 pages on the grammar of the Book of Mormon and how it has been edited, and that is the major kind of change that the text has undergone, is grammatical editing.

There will be four other parts, and next year will appear parts 3 and 4. They will appear together. There will be one on the original language of the Book of Mormon, what it was like. And then there will be … one of the parts will deal with the spelling in the manuscripts and in the editions. We’re going to talk a little bit about this today.

And then there will be, in 2018, parts 5 and 6. Five will be basically the transmission of the text—the history from the dictation to the manuscripts, the copying, the first printing, the additional editions, the kinds of changes, how accurate they were, what were the intent of the typesetters, the copyists, the editors, and so forth.

And then there will be a last part on textual criticism of the Book of Mormon, a history of it, as well as this project’s history, and the principles that have been used in trying to do this work.

So Grammatical Variation, the two green books that I showed you there, in fact all of these books, I believe, are here, volumes 1I II, III, this first part of III, and IV, are out here with BYU Studies, and they wanted me to mention that Stan and I would be out there. We can sign copies of any of these, particularly the Grammatical Variation which has just appeared.

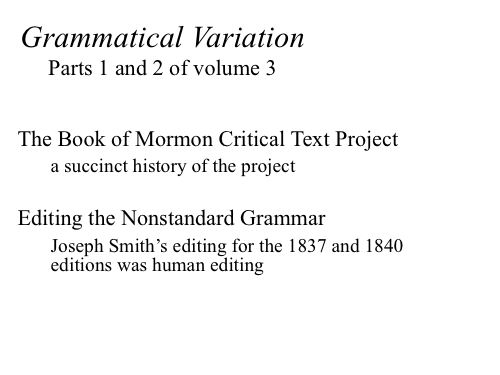

In Grammatical Variation, the first ten pages are devoted to a succinct history of the project, and I think this is important at this stage for people to realize a sort of overall view of what has been happening in the history of this project.

Then there is a chapter which I have written about Joseph Smith’s editing of the bad grammar. And some people have had the view that Joseph Smith received a second revelation when he did the editing for the second edition, that it was a revealed recension, the corrections that he made in the grammar, and it’s very clear that this really can’t be the case. Joseph Smith’s editing is human editing, and he is going through the text and making changes, and changing his mind sometimes, missing things, and so forth. It is very obvious that this is what is going on.

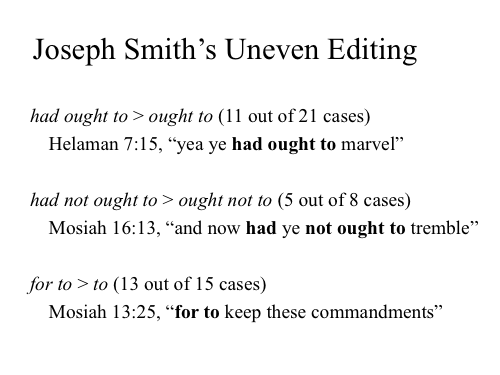

As a couple of examples of his uneven editing, the original text has: “had ought to” and when he was confronted with the text and going through the changes there were 21 of them that he could have changed to “ought to”—get rid of the “had”—but he only did 11 of them, and later editors have removed all of them, so there’s no more examples of “had ought to.”

“had not ought to”—the negative one—he changed to “ought not to” five out of eight cases; the other three were later changed.

The last one I put up here is “for to” as in “for to keep these commandments,” an older form of English. There were 15 of them that confronted him; he removed 13. I think he was trying to get rid of all of them, but he missed two. And what is interesting —these two are still in the standard text. So you get a little bit of colloquialism there. And in fact this one—“for to keep these commandments”—is in the current text.[8]

So it is uneven editing. I think this is important, because some people wish to think that any change, or anything Joseph Smith ever did, is coming directly from the Lord, and there is just no evidence for this, at all, with respect to this issue.

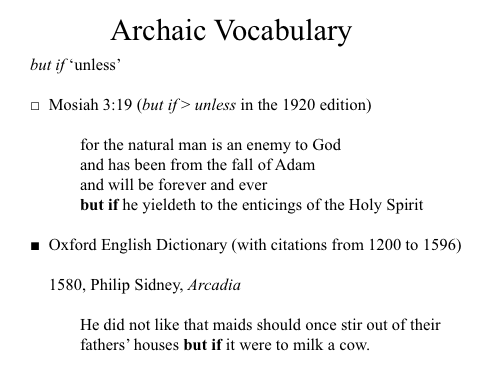

One of the important findings of the, I think, the Critical Text Project is that the original text has vocabulary which is archaic, which dates from Early Modern English. Here are three examples that I will just give and Stan, when he presents, will talk about some others.

“But if” meaning “unless” in the original text for Mosiah 3:19: “for the natural man is an enemy to God and has been from the fall of Adam and will be forever and ever but if he yieldeth to the enticings of the Holy Spirit.” This was changed by Brother Talmage in 1920 to “unless,” which is what it means. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us, though, with citations from 1200 to 1596, that “but if” means “unless.” And there is a quote from Sir Philip Sidney. But no longer in the language, yet it is in the text that Joseph Smith read off to the scribe, and was in the text until 1920.

Another one is “to counsel” meaning “to counsel with,” and this occurs twice in the original text: “counsel the Lord in all thy doings and he will direct thee for good” and “I command you to take it upon you to counsel your elder brothers in your undertakings … and give heed to their [counsel].” It is obvious here “counsel” does not mean that you are supposed to give the counsel to these brethren; you are to counsel with them and they are going to give you counsel. And this is an archaic use. And 1547, actually that is the oldest one cited in the OED. John Hooper has one: “Moses … counseled the Lord and thereupon advised his subjects what was to be done.”

And the final one is “to depart,” meaning—that I’m going to talk about here—“to part, divide, separate.” There is one in Helaman 8:11—it was in the printer’s manuscript; the typesetter just didn’t believe it; he just changed it—talking about “the waters of the Red Sea and they departed hither and thither”—and he knew that they parted—Moses parted them—so he changed it. But in older English, up to about the late 1600s, “depart” has the meaning “to part or to separate.” The Geneva New Testament: “They departed my raiment among them”—changed in the King James—it was becoming archaic by that time and they changed it to “They parted my raiment.” This is one of the things we are going to talk about in considerable depth in part 3, the third book in Volume III that will be coming out next year, all of these kinds of archaic uses in the original text.

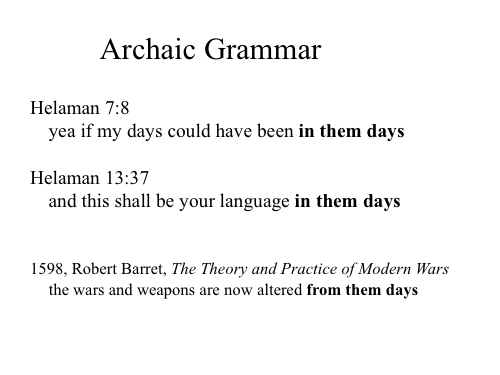

There is also archaic grammar. This is the main point of these two books: grammatical variation—that the grammar in there is non-standard for us and we have always interpreted it as Joseph Smith’s hick language. But it turns out that it is in academic writing, scholarly writing, in Early Modern English. An example: Helaman’s got, “yea if my days could have been in them days.” Most of us choke on this, and think it is dialectal. However, we find about 1600 it is used in academic writing: “the wars and weapons are now altered from them days.” And they don’t have any sense that this is somehow bad English. It ain’t. [laughter]

OK, well Stan Carmack, my collaborator, has done considerable work on this, and he has then… the third part of the grammatical variation is an essay of his,[9] about 50 pages, going through the grammar and showing that the bad grammar that we are going to talk about its editing, is in Early Modern English as non-bad English, it’s just variation in the language.

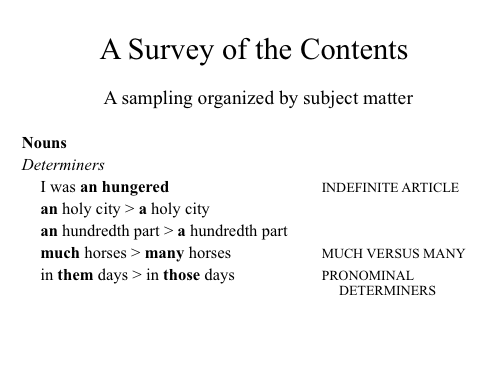

Finally, before you get to the actual going through the various sections and reading in Grammatical Variation, I have a survey of the contents.

And it is not a full index, but if you read through it, it is about 11 pages, you can just find your favorite bad-grammar issue and then it will tell you where you can read about it in the book.

So for instance, the last one—“in them days” —it was changed to “in those days” by Joseph Smith, so if you look under “Pronominal Determiners,” that is what you have got to look under, “Pronominal Determiners,” you will find the write-up dealing with “in them days.”

So when you have these books, I recommend you look through that. I think that is the way to use this. It is a reference guide.

There will be a few of you who want to read it from A to Zed. You know, it will be fun. But the others of you want to find out what Joseph Smith did about “in them days,” and whether he was right or not.

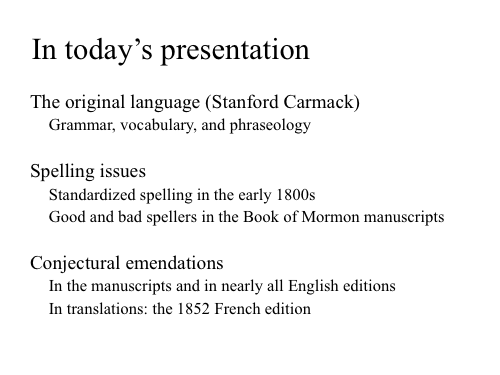

In today’s presentation, Stan will talk about the original language, he’ll talk about the grammar, the vocabulary, and the phraseology, he’ll be covering basically parts 1 and 2 and part 3. Then I will come back and talk about some issues in spelling. This is stuff that has not been published yet, and you will get to hear it for the first time. And that will be in Part 4. And then I will talk about conjectural emendations in the text. This will be in Part 6. There’s something here today which is really new, and rather surprising, I think.

Stan Carmack: I will speak briefly about Book of Mormon language, showing the usage, that there is extensive usage of archaic earlier English in the Book of Mormon. Two items of vocabulary I will talk about. And then the main part will be the systematic usage of archaic syntax. And we will talk a bit about the archaic grammar, bad grammar, and go over some items that B.H. Roberts talked about in a 1907 book,[10] and then two items of close variation that are found in Early Modern English in particular.

The verb “scatter” in the title page appears to be an archaic usage. A close reading will tell you that it is slightly different from how we use it today. Here is the Oxford English Dictionary entry, their definition 2d; the dagger indicates that they consider that to be obsolete. It means “separate.” “…[W]hich is a record of the people of Jared, which were scattered at the time the Lord confounded the language of the people.” We know that the people of Jared were not dispersed; they went in a group. So they were separated together from the main body of the people at the tower.

We can find examples in Early English Books Online, these two from 1577 and 1629, where we have people as well who were scattered, individuals in this case. “The Earl was scattered from his company,”—he was separated from his company. A sermon “when one was scattered from GOD, how to gather him to GOD again.”

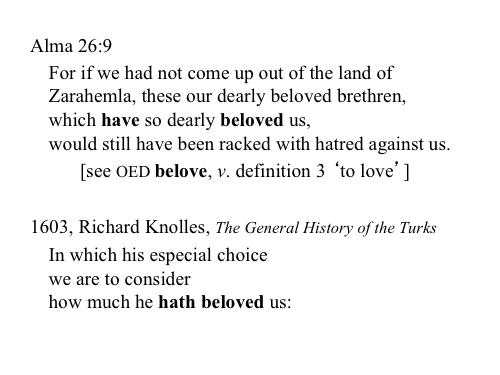

Another one, the last one I will mention here, is the verb “belove,” used to mean simply “love,” in the active voice. If you go to Webster’s 1828 Dictionary you will find that Webster himself says that in American English, the verb “belove” was not used in the active voice in the 1820s. By then it had dropped out of the language. You go to the Oxford English Dictionary under definition 3 it gives you the archaic meaning of love in the active voice, with some examples. There are two prose examples, and one example from poetry, the latest example from the poet Robert Southey.

And here is an example from 1603; we found two of these in Early English Books Online, where “belove” is used in the active voice to mean “love”—“In which his especial choice we are to consider how much he hath beloved us.” So that is very close to what we have in Alma 26:9, we have the present perfect tense there: “Our dearly beloved brethren, which have so dearly beloved us.” And there are two more in Alma.

Now I will talk also briefly, but I will touch on more points here of systematic archaic syntax in the Book of Mormon.

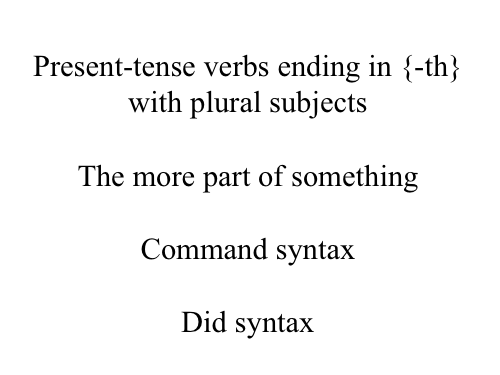

The first one I will talk about is the use of the archaic verbal ending “th” when you have a plural subject. So if you read the earliest text you will encounter many of these. If you read the 1981 text you will only encounter fewer than five, I believe. We will talk about the “more part” usage briefly, verbal complementation after the verb “command,” and the past tense with the auxiliary “did.”

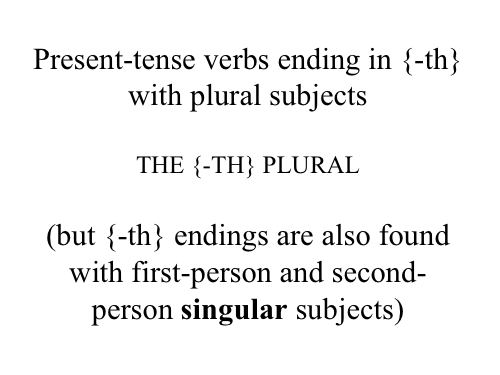

First we will talk about the “th” plural. This is what linguists have called this usage; this is an Early Modern English usage in particular that came out of Late Middle English. And the “‑th” endings are not always associated with the plural. You can also get these with first person singular and even second person singular subjects. And there are some instances in the Book of Mormon with first person singular subjects.

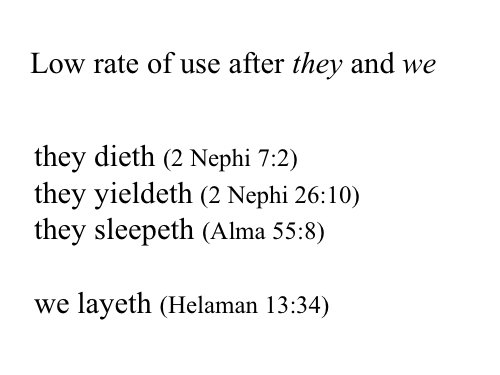

What we find in the Book of Mormon is there is a low rate of use of the “‑th” endings after the pronoun “they.” So when we have present tense examples we only find three of these, and one of these is a modification of an Isaiah passage, the first one you see there. That is not found in Isaiah: “they dieth.” We find that in Early Modern English in the 1500s. “They yieldeth”—we find “both of them yieldeth” in Early Modern English. “They sleepeth”—we have not found that exact one. We have found examples that are similar, such as “they reapeth.” And there is one use of “we layeth” in the Book of Mormon, one use of the “‑th” plural with “we.” So this “‑th” plural is used sparingly with the pronouns, directly after the pronouns.

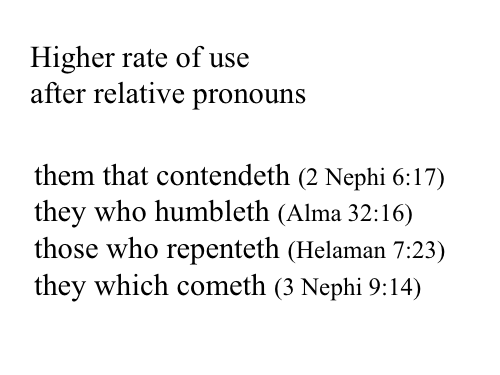

But the interesting thing is that we find it used much more heavily after relative pronouns. So I looked in particular when you have a relative pronoun where the antecedent is a third person plural pronominal, either “them,” “they,” or “those,” as you see in the examples here. In the Book of Mormon the rate is four to five times higher after the relative pronoun—the rate of the usage of the “‑th” ending, after a plural relative pronoun when you have “them,” “they,” or “those” before it, it is four to five times higher than the case where the subject is “they,” as we saw in the previous slide. This differential rate usage is found in Early Modern English; the same thing occurs in Early Modern English, so there is an awareness, somehow, in the text, of this sensibility, of this tendency of Early Modern English. So the usage is not merely an over-use of the “‑th” ending, rather it is a somewhat sophisticated use.

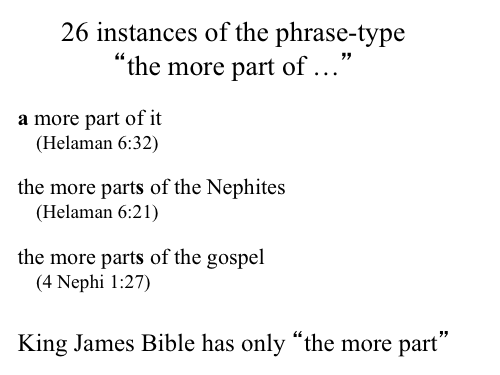

We will talk a bit about “the more part,” how it is used in the Book of Mormon.

We have 26 cases of this in the Book of Mormon. And they all have the preposition “of” after “the more part,” or “a more part,” or “the more parts.” You see those three examples? Those are the exceptional examples, where we have a slight variation. We have an indefinite article in one case, “a more part of it”; and twice we have plural parts: “the more parts of the Nephites” and “of the gospel.” These are rare in Early Modern English, but they are found during that period. We note that the King James Bible has only “the more part,” nothing following it, and it only occurs twice, in the Book of Acts. So the Book of Mormon is always slightly different from the biblical usage.

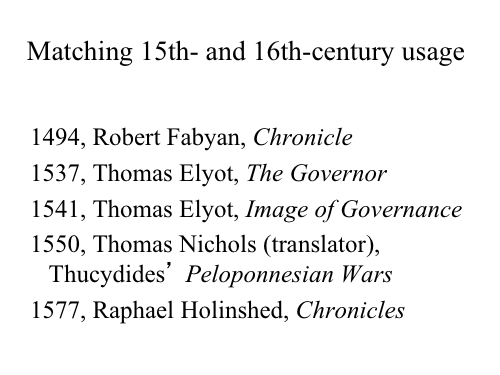

In my investigation of this, looking at many texts from the Early Modern period, I found five, these five texts you see here, that matched the Book of Mormon well.

The first one, Fabyan’s “Chronicle,” has one instance of “a more part of the province.” That again is a rare usage, and we find that in the Book of Mormon. The 1577 “Tudor History,” which has more than two million words. Holinshed’s “Chronicles” has more than one hundred of these, but because it is so long, the rate of usage is actually below the Book of Mormon. The other three have rates that slightly exceed the Book of Mormon’s usage rate. These are the only five that are close to the rate of usage of the Book of Mormon, so we have to go back 250 years before the Book of Mormon, to reach a book that uses “the more part” like the Book of Mormon.

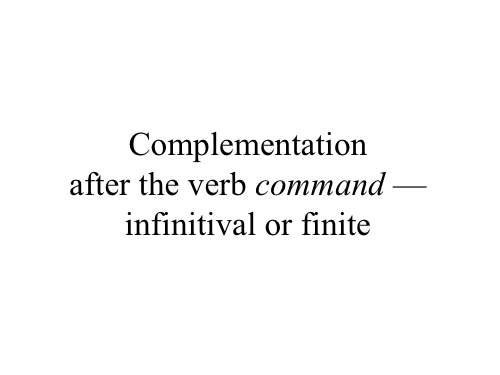

I will talk briefly about the verb “command” when it has a verbal complement. So normally in Modern English we use an infinitive when we have a verbal complement after the verb “command,” and or verbs like it, although we still have verbs where we use finite complementation such as the verb “demand” in Modern English.

An example of what I am talking about here, the finite complementation, is “he doth not command us that we shall subject ourselves to our enemies.” So we can see a “that” clause immediately after the verb “command,” with the finite auxiliary “shall,” so we know that is the finite complement.

The Book of Mormon has this particular structure eighty percent of the time, which is a very high rate. Eighty percent of the time we have a “that” clause, or a finite clause, after the verb “command.” The King James Bible only has this twenty percent of the time. And by Joseph Smith’s time, databases tell us that in finite complementation, “that” clauses were used less than five percent of the time. In looking at the Early Modern English record we found a match in the first printed book in English. There you see it, William Caxton’s translation of a French work. In that book, the complementation is finite eighty percent of the time, just like the Book of Mormon. It is very hard, it is rare, that we find books that have complementation that is finite more than fifty percent of the time. Here is another one, a 1483 translation, by Caxton, out of Latin, “The Golden Legend.” The complementation there is finite sixty percent of the time and it is a fairly good match with the Book of Mormon. The earlier book, the first printed book in English, is the best match in this regard.

Another item that is a good match with this lengthy book, the 1483 book, is that it has 65 cases where you have a doubling of the indirect object, followed by a “that” clause with the indirect object re-expressed in the “that” clause—so some verb form of the verb “command” with an indirect object “X,” and a “that” clause where the subject “X” is the same as the indirect object. And the Book of Mormon has a very high number of these, 74, so basically we have to go back 350 years from the Book of Mormon to reach a book that has the levels of usage of this particular structure.

I will talk about past tense expression now, and also about some present tense expression with the auxiliary “do.”

A Swede, Ellegård, studied this, he studied the historical use of the auxiliary “do” in English, how it changed over time, in 1953, because there was quite a bit of change. And we know that in English, when we express negation, we use the auxiliary “do.” When we ask questions we use it. But in affirmative declarative sentences without emphasis, we do not use it, although there was a time in English, as we see in the Book of Mormon, where that was the case.

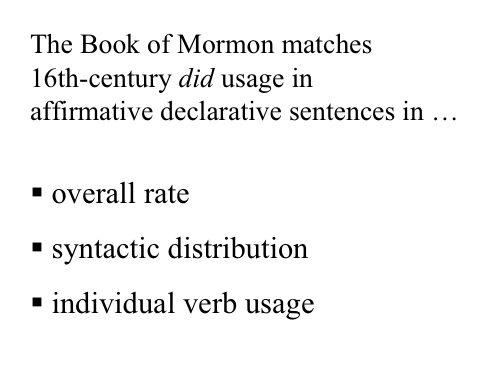

The Book of Mormon matches the 16th-century in its “did” usage in affirmative declarative sentences in at least three ways, so the match with the earlier period is not simple. We have the overall rate, which is only a good match with the 16th century. The distribution of “did” and the infinitive, whether they are close together or whether they are separated, is also a very good match with the period. And individual verb usage—so, some verbs use “did” with the infinitive in Early Modern English quite frequently and the Book of Mormon shows the same tendency. Other verbs did not use it. Again, the Book of Mormon does the same thing. For instance, the verb “die”—you do not get “did die” in Early Modern English very often and we do not have that in the Book of Mormon. It is always the simple past tense, “died.” “Did minister” is frequent in the Early Modern English, and very high rate in the Book of Mormon.

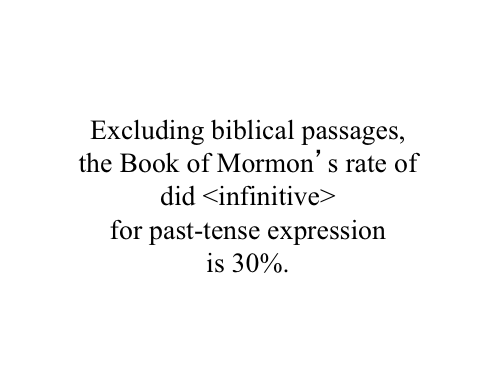

If you exclude biblical passages from the Book of Mormon, the lengthy Biblical passages, you get a rate of approximately thirty percent “did” usage for the past tense. The time we see that is in the second half of the 16th century.

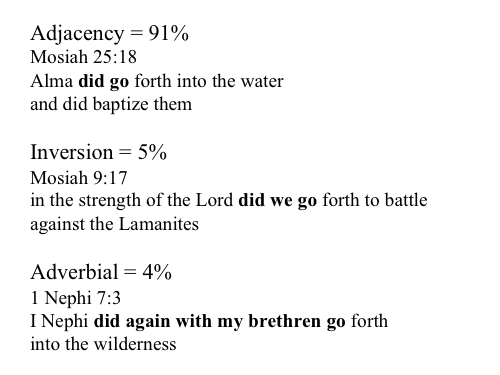

Here is the syntactic distribution—rather simple, only three things we look at here: whether “did” and the infinitive are adjacent—“Alma did go forth into the water and did baptize them.” We have inversion of “did” and the subject—so “did” is separated from the infinitive by the subject—“in the strength of the Lord did we go forth to battle”—that only occurs five percent of the time, and the time when we see that inversion five percent is in the 16th century. There is an intervening adverbial, or an adverbial phrase, or just an adverb, four percent of the time. Those last two increase in frequency in the 17th century, adjacency decreases, and the Book of Mormon is not a good match with the 17th century. And by the 18th century this usage had largely dropped out of the language and, according to linguists, was dead by the middle of the 18th century. We have to go back to the year 1677 or before to find a book that has usage like the Book of Mormon uses “did.”

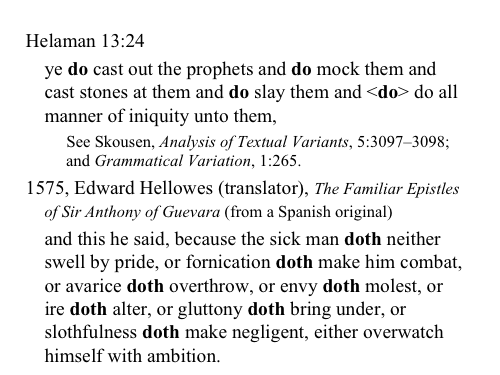

Here is an example of how “do” is used heavily—the present tense auxiliary “do” is used heavily in Helaman 13:24; we see four of these. The last one was deleted. We can find that in Early Modern English; it is not common, but we do find it. 1575 example, we see seven cases of “doth,” present tense “doth” used here with the infinitive, to give you an idea of what can be found during this period in texts. And I’ve shown examples of “did” matching with Early Modern English.

Talk about archaic grammar—in many cases we do not encounter this unless we are reading the Yale edition:

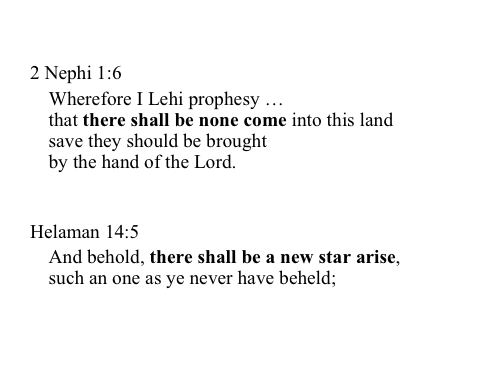

“Wherefore I Lehi prophesy … that there shall be none come into this land save they should be brought by the hand of the Lord.” “[S]ave they should be brought” is also archaic and rare from Early Modern English, but in this case we are focusing on “there shall be none come”—the “be” was deleted. Helaman 14:5: “And behold, there shall be a new star arise”—this is a literate archaic usage of the past, although we have found one Modern English instance of this.

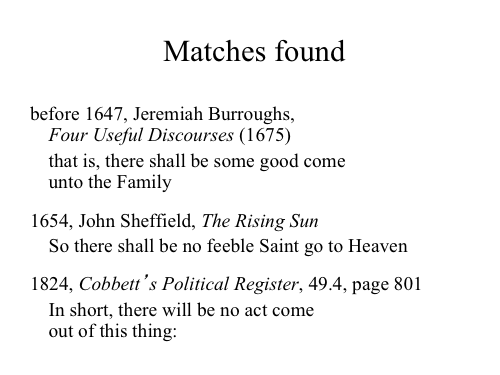

But the best match with “there shall be” is found in these two from the middle of the 1600s— “there shall be some good come unto the Family”; “So there shall be no feeble saint go to Heaven.” And there is the Modern English example, from British English, literate usage of the past.

We have found that the bad grammar is almost always archaic grammar.

B.H. Roberts was one of the few who ever gave specific examples of the bad grammar. I’ll use his book from 1907[11] to show some of the ones he mentioned.

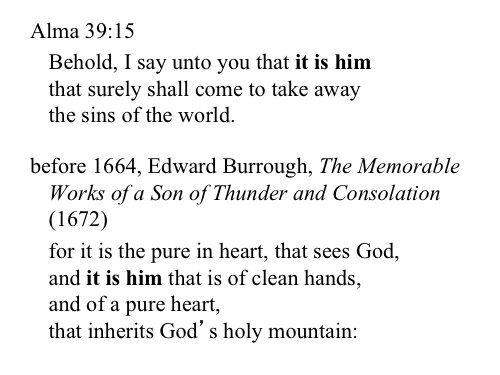

Here we have the subject complement, in this case which takes the objective case. So that one can be classified as bad grammar. Normally in the Book of Mormon we do encounter “he” in this instance—“it is he”—but there is this one instance with it is “him”; and here is a match from the Early Modern period: “for it is the pure in heart, that sees God, and it is him that is of clean hands, and of a pure heart.”

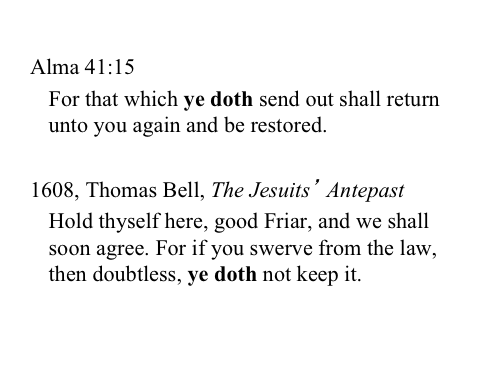

Here is another one that he pointed out: “For that which ye doth send out shall return unto you again and be restored.” So here there were two objections that could be raised. He did not specify but “ye” is used with a singular reference here, Alma speaking to Corianton, and then we have “doth” instead of “do.” Here is a match with that from 1608. And in this case, in addition to the “ye doth,” what we see here is the close variation in the pronominal use—we have a “thou” form, “Hold thyself here, good Friar”; we have a “you” form subject, “[f]or if you swerve from the law”; and then we have a “ye” form; see the fluidity in usage of the past. We see that in the Book of Mormon.

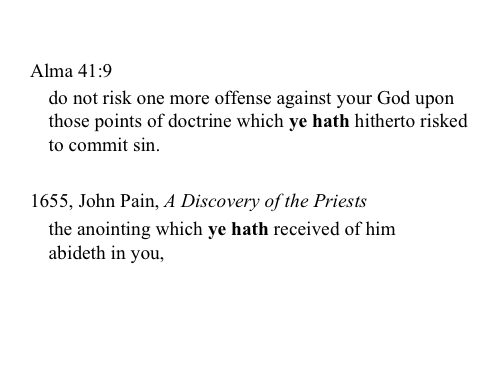

Here is an example of “ye hath” that B.H. Roberts pointed out: “those points of doctrine which ye hath hitherto risked to commit sin.” And here is an example from the middle of the 17th century: “the anointing which ye hath received of him abideth in you.”

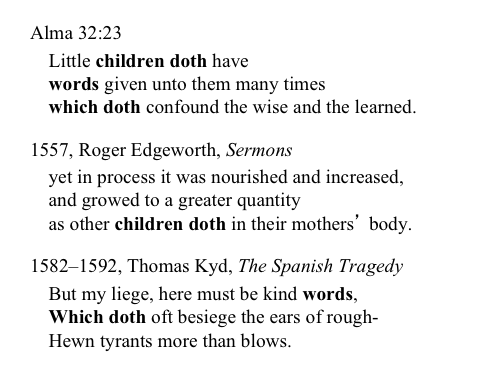

Some more examples of the “th” plural, these are found in the Book of Mormon. They are always the less frequent forms, but we do have quite a large number of them in the Book of Mormon. “Little children doth have words given unto them many times which doth confound the wise and the learned”; so “children doth” and “words which doth.” Here is an example of “children doth” from 1557. We can find “doth” used with other subjects, but this particular one was a precise match with “children.” And “words which doth,” this was the other precise match that we found from the playwright Thomas Kidd, “But, my liege, here must be kind words, Which doth oft besiege the ears of rough-Hewn tyrants more than blows.”

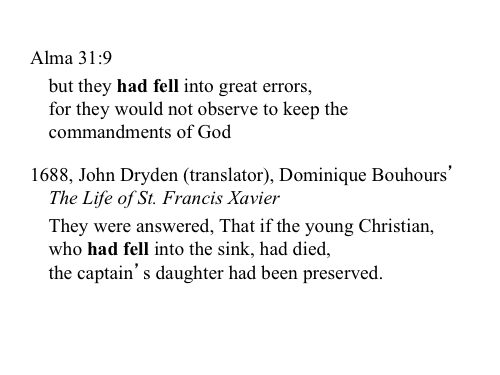

Another one that B.H. Roberts pointed out was “had fell.” Here we have the pluperfect, the past perfect “had fell,” and we have a past tense form “fell” used for the past participle. This was most common in the 17th century in Early Modern English and it was very common or most common with the past perfect and also with modal perfects. And here is an example of that. These are not hard to find if you look in databases such as Early English Books Online. And we have more than one of these in the Book of Mormon. But again, the predominant form in the Book of Mormon is “had fallen.”

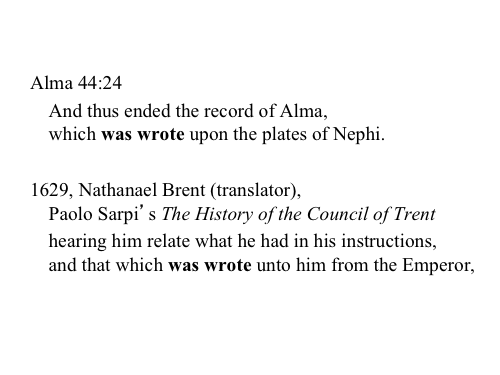

Here is one that is rare, though. This is the only case in the Book of Mormon where you have passive with the past tense past participle: “And thus ended the record of Alma, which was wrote upon the plates of Nephi.” That sounds very bad to our ears. We find this in the Early Modern period, but it is not common. Again, the passive resisted this leveling of the past-participle to the past tense form, but it can be found during that period: “and that which was wrote onto him from the Emperor.”

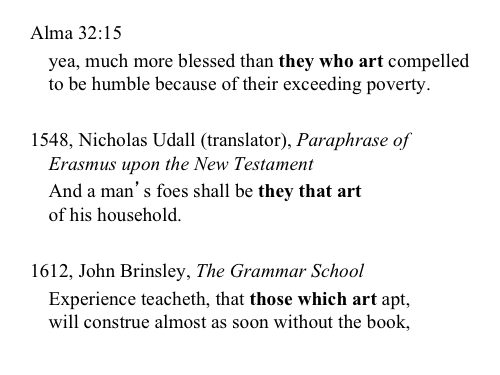

Here is an interesting one that B.H. Roberts pointed out, the use of “art” where the subject is not “thou.” We can find this with plural subjects and often after the relative pronoun. In fact, the Book of Mormon usage is restricted to cases after a relative pronoun or after a conjunction: “much more blessed than they who art compelled to be humble because of their exceeding poverty.” And here are two examples with “they” and a relative pronoun: “they that art” and “those which art.”

Finally, there is close variation in the Book of Mormon which is characteristic of Early Modern English. We will find the best matching during that period; for instance, I have mentioned and shown examples before of “they was” and “they were” used in Alma 9, how that is very close together. And we can find examples of that in Early Modern English with no discernable difference in tone between “they was” and “they were.”

I’ll mention here … we will see two examples.

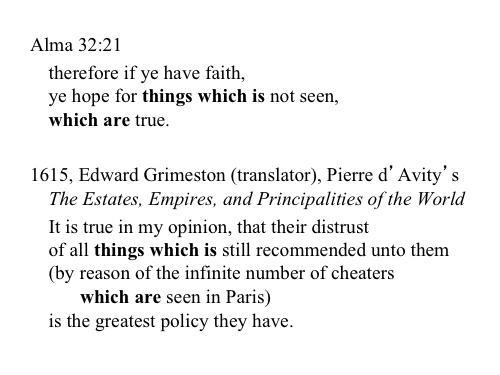

This from the famous scripture, Alma 32:21—“therefore if ye have faith, ye hope for things which is not seen, which are true.” Close variation of “which is,” plural, and “which are,” switching right to “which are” with the same antecedent.

Now when you look at Early Modern English, I have found more than a hundred examples of “things which is” and “things that is,” maybe even more than two hundred. And that is, I believe, in Early English Books Online Phase I, so that’s fewer than half the books that have been digitized so far. So this was not uncommon in Early Modern English, and we see it quite frequently in the Book of Mormon. “Things which is,” you can find it in the Early Modern English Bible as well. And here is Edward Grimeston, the translator from 1615, using “things which is” and then “cheaters which are” very close together.

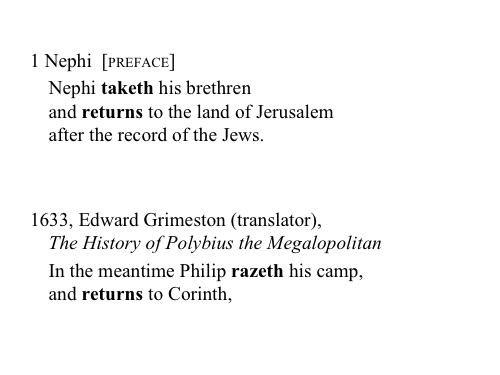

The last one I will mention is also by Grimeston here, where we have a “th” ending, followed immediately by an “s” ending, close variation. “Nephi taketh his brethren and returns to the land of Jerusalem after the record of the Jews.” Grimeston used, “In the meantime Philip razeth his camp, and returns to Corinth.” In fact, this translator, I have found that he has used a few of these, and that is partly because he translated so many lengthy works. Thank you.

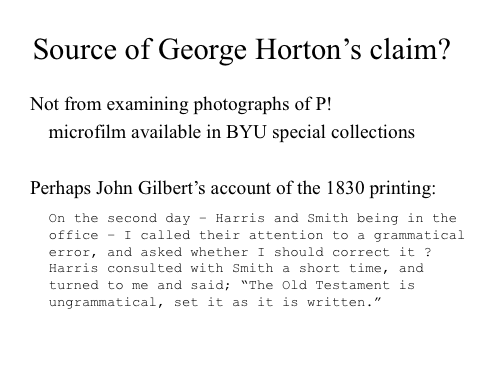

Royal Skousen: So, I want to turn to part 4, which will deal with spelling. Let’s first look at a work by George Horton published in the Ensign of December 1983, “Understanding Textual Changes in the Book of Mormon.” I’m going to talk about every claim he made about spelling—they’re all wrong. “[T]he spelling in the first edition was Oliver Cowdery’s.” The printer’s manuscript, or 85%, was written in Oliver Cowdery’s hand and chiefly the one used by the typesetter. The typesetter was John Gilbert.

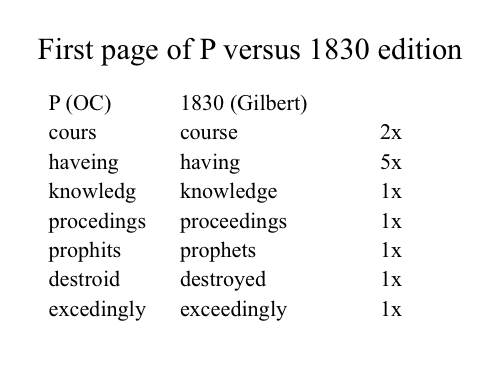

Here’s the first page of the printer’s manuscript in Oliver Cowdery’s hand and compared against how Gilbert set the words. Every misspelling that’s in the manuscript is in standard spelling in the 1830 [edition.] It is not Oliver Cowdery’s spelling.

How did George Horton come up with this idea? Well, it didn’t come from looking at the printer’s manuscript. He didn’t look at it. He could have gone over to the BYU Library and found it in the archives in a microfilm version. But he read instead from Gilbert’s account of the 1830 printing: “On the second day—Harris and Smith being in the office—I called their attention to a grammatical error, and asked whether I should correct it? Harris consulted with Smith a short time, and turned to me and said; ‘The Old Testament is ungrammatical, set it as it is written.’” And apparently George Horton interpreted that to mean that he was instructing the printer to literally set it letter for letter, whatever the printer’s manuscript had, but that isn’t what was intended here. He meant—keep the grammatical errors, but set everything else according to the standard spellings—[that] is what was the real assumption.

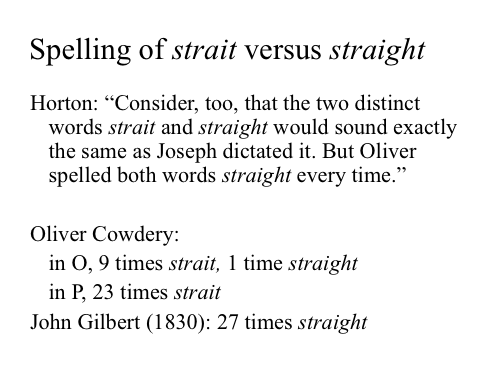

Then Horton says, “Consider, too, that the two distinct words strait and straight would sound exactly the same as Joseph dictated it. But Oliver spelled both words straight [with a ‘gh’] every time.” Well, this is because he has assumed he could look in the 1830 [edition] and see that the 1830 typesetter spelled twenty-seven times “straight” with a “gh.” But if you look at the actual manuscript, you see Oliver Cowdery spells it almost every time, both manuscripts, without the “gh.” It’s just the opposite—there’s one case with “gh”—we’ll give him credit there.

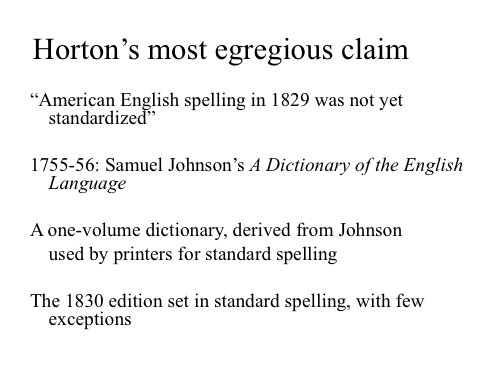

Next his most egregious claim: “American English spelling in 1829 was not yet standardized.” I hear this all the time—people telling me [this] as an explanation of various errors in the text. It is totally false.

In 1755-56 Samuel Johnson published his dictionary of the English language. It had all these wonderful citations of language usage. But people created one-volume versions of Johnson’s dictionary over the next fifty years, took out all the citations, maybe added pronunciations and so forth.

The 1830 edition, the typesetter, if he had a question about spelling, would have opened up his dictionary and would have looked at the spelling. He follows the standard spelling. It is standard in printing—not true in hand-writing, but in printing.

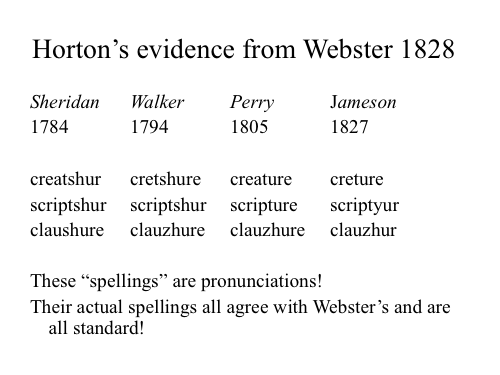

Horton’s claim, he says, “As late as 1828, American lexicographer Noah Webster noted that five dictionaries were available to him. Examples from four of those dictionaries show the variations in spellings commonly accepted at the time Oliver was taking dictation from the Prophet.”

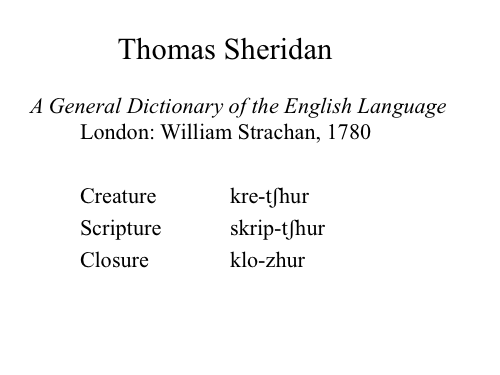

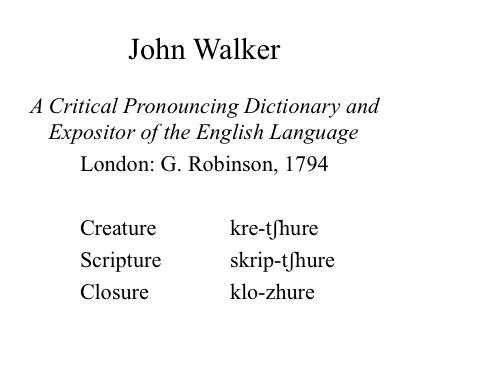

Well, you should go look at Webster’s 1828 on this page. And it’s got a long list of five dictionaries—actually, I’ve got four here—these are the ones that Horton puts. And you’ll notice underneath—Sheridan, Walker, Perry and Jameson—these various spellings. These spellings are not spellings—they are pronunciations—in these dictionaries. Their actual spellings all agree with Webster because they are all following Johnson, and they’re all standard.

Here’s [Thomas Sheridan] —by the way, these are not American dictionaries for the most part; they are London ones—Thomas Sheridan, you look up in his dictionary, I went online and got them: creature, scripture, closure. Those are his spellings; there’s his phonetic representations.

John Walker, same thing, London dictionary.

Jameson, London dictionary, 1828, same spellings. The Book of Mormon will have these same spellings.

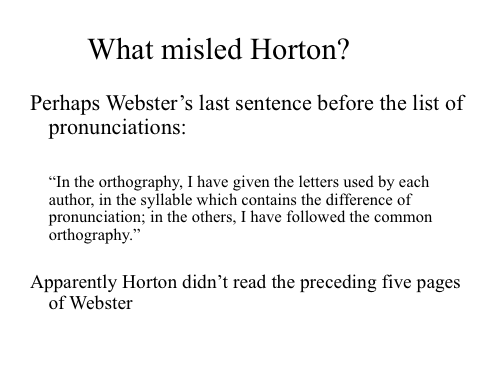

What misled Horton? Well, I think it’s Webster’s last sentence. George liked to look at the last sentence and not look at anything else. This is what Webster wrote before his long list of all these pronunciations—see, Webster is trying to convince you to buy his dictionary because he has the superior pronunciation system—so he’s going to list his opponents and their pronunciations: “In the orthography, I have given the letters used by each author, in the syllable which contains the difference of pronunciation; in the others, I have followed the common orthography.” He’s [Horton] muddled this all up and thinks these lists are the common orthography. Horton didn’t read the preceding five pages in the 1828 dictionary because that’s where Webster goes over what he is talking about—he’s [Webster] talking about pronunciation and how to represent it.

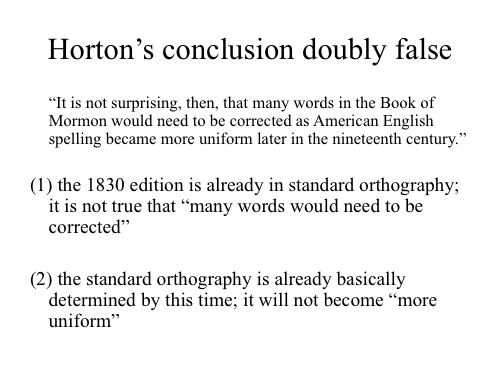

His [Horton] conclusion is doubly false. You make the beginning conclusion false and everything from it is going to be pretty much false.

“It is not surprising, then, that many words in the Book of Mormon would need to be corrected as American English spelling became more uniform later in the nineteenth century.” Well, first of all, the 1830 edition is already in standard orthography. It is not true that “many words … would need to be corrected.” Two, the standard orthography is already basically determined by this time. It will not become “more uniform” in any reasonable sense.

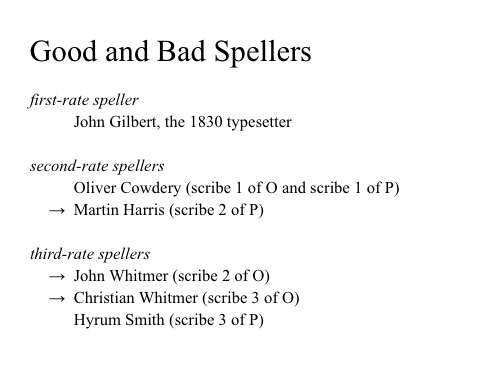

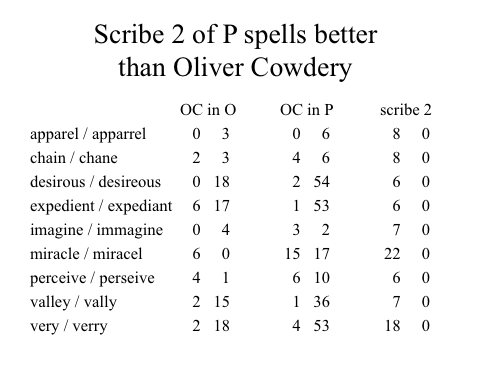

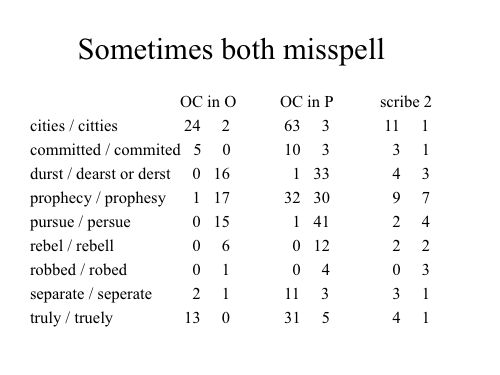

Well, in the manuscript I want to talk about one speller, which is sort of amazing. There is one first-rate speller; it is John Gilbert, the typesetter. There are two second-rate spellers: Oliver Cowdery—he’s pretty good but some words he just can’t spell—and Martin Harris. I think it is Martin Harris that is scribe 2. I’ve got an arrow in front of that, which means I think the evidence points to Martin Harris. In part 5 I will go over all of the evidence to indicate that I think it is Martin Harris as scribe 2 of the printer’s manuscript, the unknown scribe. There are three third-rate spellers, all farm boys—John Whitmer, Christian Whitmer, Hyrum Smith—they are really bad spellers. And I’m not going to go into that here, but it will be in part 4.

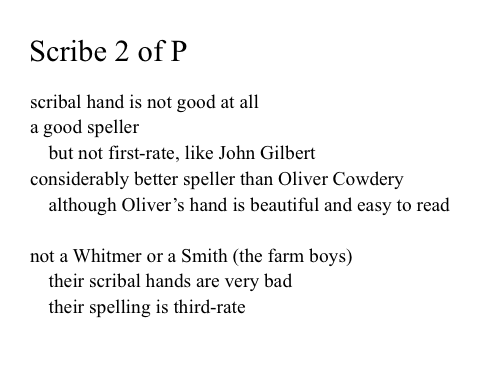

Scribe 2 of “P” [Printer’s manuscript]: I’ve always thought he was a bad scribe. He is a bad scribe. His hand is really hard to read. He causes trouble. He isn’t a great speller, not like the typesetter, but he is good, and he’s much better than Oliver Cowdery. Now some people have suggested that this unknown scribe might be a Whitmer or a Smith. I doubt it very much because the Whitmers and the Smiths don’t know how to spell well at all. So I don’t think it’s a Whitmer or a Smith.

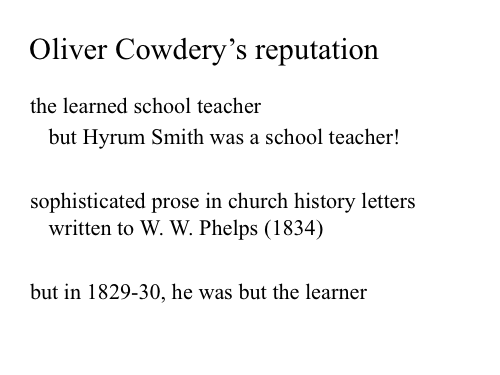

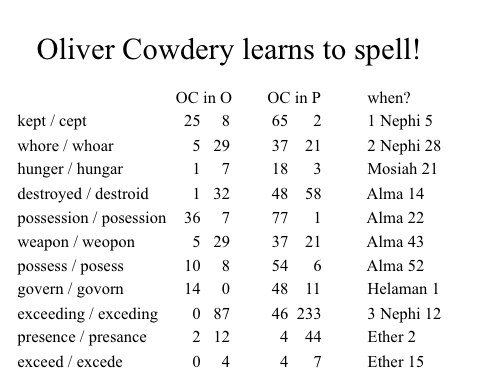

Oliver Cowdery has a reputation as the learned school teacher, but we should note that Hyrum Smith was also a school teacher; didn’t take much to be a school teacher. They were mostly [itinerant] school teachers. Oliver Cowdery has very sophisticated prose that he wrote in Church letters written to W.W. Phelps in 1834. You think he’s pretty erudite, and that’s probably true five years later, but in 1829 he isn’t. In 1829 and ’30 he was but the learner. But we will see he learns how to spell as he is doing the Book of Mormon. He would take in the sheets. He would write them out in the printer’s manuscript, take them to the printer, the printer will set the type in correct spelling, and then he will proof it. And as he’s going through the proofing, he begins to notice, “Hey, wait a minute, I’m misspelling that word.” And he changes his spelling. This shows the typesetter isn’t following Oliver Cowdery; Oliver Cowdery is learning to follow the typesetter.

Well, let’s look at it.

First of all, here is scribe 2—this amazed me. The hand of scribe 2 is so bad you’d think he is a terrible scribe, but here, look at these spellings. I mean, I can’t even spell “apparel.” The first one [apparel] is the correct one; the second one [apparrel] is the incorrect one, in case you are having a problem. Now with “chain,” you know, OK, I think most of us know how to do that one. Oliver sure didn’t, but scribe 2 did. You can go down to “imagine,” “expedient,” all of these. Scribe 2—it was surprising to me—over and over he’d be correct all of the time, which means he knows how to spell it. He’s not just guessing right.

Now, sometimes scribe 2 does make mistakes. I’ve listed some there and there’s Oliver Cowdery, can’t spell them either. It’s very rare when Oliver can spell a word and scribe 2 can’t spell it, very rare.

But this is Oliver Cowdery learning to spell and we know when he learned to spell the word, because when he learns it, all of a sudden he gets it right and it’s right almost all the time to the end of the printer’s manuscript. Even “kept,” he’s misspelling it with a “c” until 1 Nephi 5. He learned that one really early. He must have said, “Oh boy, I’ve been doing that one wrong.” So he learned that one and “whore” he was misspelling up to 2 Nephi 28 and he suddenly realized, “Oh wait, I’ve got to spell this right.” And he learns how to spell it.

You can go down here, it’s sort of interesting, I like “exceeding”—he had only one “e” in it all the way through the original manuscript, through the printer’s [manuscript], he never spelled it with double “e” and all of a sudden, he got to 3 Nephi and we see him spelling it right and he spells it right all the way to the end. He learned how to spell it. Now, I like this about Oliver because when he becomes erudite, he becomes a lawyer, he knows how to learn. This is actually a good sign. He’s a lousy speller—second rate—but he’s improving. Now, we don’t think that scribe 2 really did too much proofing. And there isn’t any evidence that he learned how to spell and he changed his spelling on his errors.

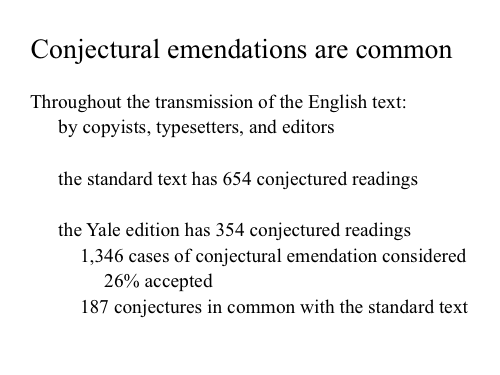

The other thing I want to talk about are conjectural emendations. A lot of people think that you shouldn’t ever make a conjectural emendation. A conjectural emendation is when you look at the text—there’s a reading—you go look at all the other earlier editions or manuscripts and you see other readings and none of them seem to work for you. So you decide, “I’m going to change it. I’m going to come up with a new one.” Now, that situation has occurred throughout the history of the Book of Mormon. Oliver would be copying from the original [manuscript] to the printer’s [manuscript] and he didn’t like what he was reading in the original and he’d say, “Oh, I think that really should be this,” and he’d change it. That is a conjectural emendation. And then the typesetter might be looking at what Oliver wrote and said, “Oh, that can’t be right,” and he would change it to something else. That’s a conjectural emendation. He’s emending it and he’s conjecturing. They are very common. The current LDS text has 654 conjectural emendations—not all done in 1981, but done in the past throughout its history. The Yale edition only has 354, a little more than half as many. It’s interesting that 187 of the conjectures are in both of them. So there is some overlap in accepting some of these.

I will just briefly note Oliver Cowdery made 131 conjectures in copying from the original [manuscript] to the printer’s [manuscript] and 120 are in your current text, but 39 in the Yale. So we reject … 30 percent is pretty good. John Gilbert even is higher. He makes conjectures, trying to figure out what the printer’s manuscript reads—47 percent accepted.

Joseph Smith is low. Joseph Smith felt to change things a lot of the times when there really wasn’t any reason to do it. And so we count these as conjectures because if I made them they would be conjectures. So it’s very low for his, about one out of six.

Orson Pratt [editor for the 1849 edition] did a few, the Richards brothers [editors for the 1852 edition] did a few, Orson Pratt [editor for the 1879 edition], and most of them are in our current text.

German Ellsworth, a mission president, made some conjectures, seven of them in the current text. Even mission presidents can influence the text. James Talmage made a lot of conjectures—he was trying to clean up the text much like Joseph Smith, and one out of six are accepted. The scriptures committee in ’81 made ten—they are much more conservative, and about 40 percent are in the Yale text.

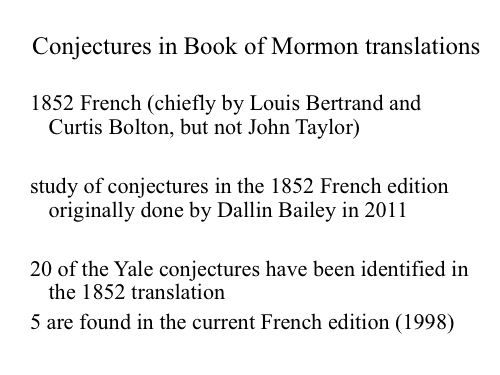

What I want to talk about here at the end are translations. One of the things that I’ve discovered is that we have had conjectures in translation way back. There are two periods of time when translators wanted to make conjectures. The first was in the early translations. And you see, we’re going to talk about the French one, the 1852. It says on the title page that John Taylor is the translator along with his counselor. And he didn’t. He didn’t know French so he isn’t the translator, but the real translator is Louis Bertrand and he … nobody’s really going to stop him, but he’s really interested in trying to make the text make sense and actually, I’ve found, he’s got 20 of the Yale emendations and I’m going to go over five of them. They’re really quite interesting.

This work was first done by Dallin Bailey, a student in my Book of Mormon textual criticism class. Sometimes the students, they learn the language on their missions so they go out and look at this. The other place where you get lots of freedom in the translators is from about 1940 to 1970 or so, where translators were usually one person that joined the Church, native speaker of the language, and nobody is really checking them, but they are acting in good faith. So there are twenty that I’ve found thus far in the French 1852 [edition], really sort of amazing.

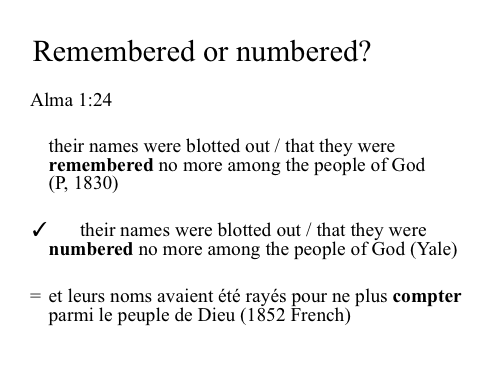

The first one: “their names were blotted out / that they were remembered no more among the people of God.” This is in Alma 1:24. I think it’s “numbered” and there’s lots of internal evidence that people are numbered, they’re not remembered, in this sense, when you are on the Church rolls. We excommunicate people, we sure still remember them, but they’re not “numbered.” In any event, I conjectured that, and we have it in the French 1852 [edition], not in the current French, but now it’s back to being “remembered,” but it is the word “to count,” in the French, you see it there in bold.

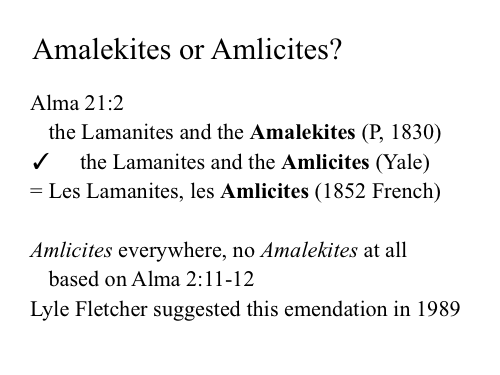

The next one is Amalekites versus Amlicites, and there is considerable internal evidence that there are no Amalekites in the Book of Mormon. This is a biblical overlay by Oliver Cowdery, so they should always be Amlicites. The 1852 [French edition] goes in and changes every “Amalekite” to “Amlicite.” The translator thought it was an error, and it agrees with what the Yale text has.

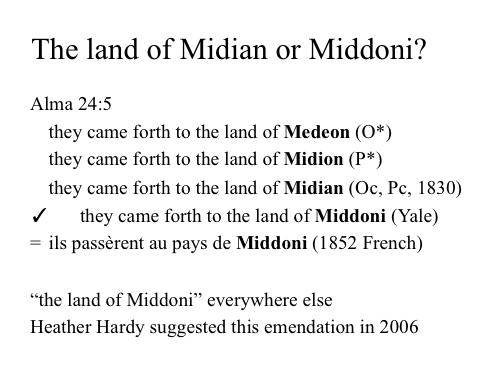

The land of Midian: this is the way the text reads, but it’s the only one, and everywhere else it’s talking about this land of Middoni. And Heather Hardy suggested in 2006 that it was the land of Middoni and I immediately saw that she was probably right. Well, in 1852 the translator came up with this too and the French one has Middoni, as you can see there. It’s quite striking. Who is validating whom here, Heather?

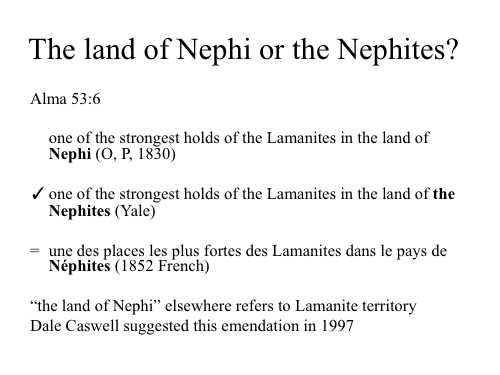

The land of Nephi or the Nephites: “one of the strongest holds of Lamanites in the land of Nephi.” Well, the Lamanites live in the land of Nephi. What is this? Well, it probably should be “the land of the Nephites.” This was an emendation suggested by Dale Caswell in 1997, but this is indeed is how the French one reads in 1852. So these are several of them.

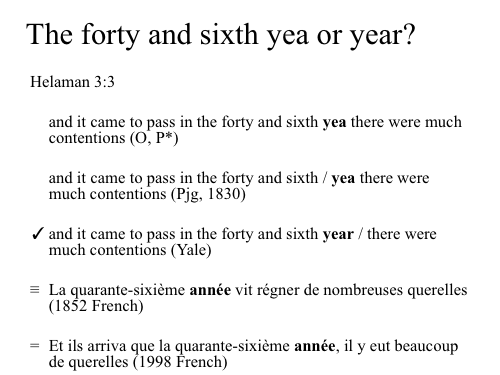

And the last one: “the forty and sixth, yea” is the way the current text reads in Helaman 3:3. “It came to pass in the forty and sixth yea there were much contentions”—well, I think it’s “many” now, or something. But in any event, “yea” is still in there, but it’s an error for “year.” And the 1852 French [edition] has—it doesn’t have the word “oui” meaning “yes” thrown in; it is very un-French—they saw that “yea” should be “year,” which is correct. Interestingly, the 1998 translation, which is highly supervised, has this emendation. The French translators just couldn’t take “yea” being in there. And of the twenty, five of them are in the current French edition.

One of the things which I haven’t done is read through that whole 1852 [French edition] to see if there are other conjectures that they put in—that Louis put in—that maybe I should consider. And maybe there’s a Mandarin one I should read all the way through. And maybe there’s—well, there’s … see, some of you could do this. It’s a wonderful area. Well, these are some of the things that will be in the completed volume III. We touched upon parts 1, 2, and 3. Stan talked about those, and I’ve talked about the spelling of 4 and of 6, the conjectures. There will be probably another 2,600 pages for your Sunday afternoon reading. Thank you.

[Applause]

Q: [Reads question silently]

A: So, we’ll just make a quick comment about the biblical uses in the text. People have really emphasized the large portions from Isaiah and Matthew 5-7 that are coming from the King James Bible text as a base text—there are changes, but they’re in the Book of Mormon—and the problems that arise from this. This will treated in part 3 of the upcoming work, and we make complete comparison of the differences. And a lot of it is in volume IV already.

There is another more interesting part that needs to be considered about the King James Bible. There is all this phraseology in the Book of Mormon text which is sort of taken from different parts in a given passage, just woven together. It isn’t like somebody is taking something, looking at Hebrews and says: “I’m going to do a little Midrash on Hebrews and make a comment here and throw it in the text.” It’s just phraseology that happens to show up in Hebrews and it’s being used in a way that’s different than the way it is in Hebrews. And then there’s something from Exodus in that same passage, a little phrase, and it’s woven. It’s like somebody is translating this, knows that King James text so well, and it can just use it. It isn’t like Joseph Smith spending all night whipping through his Bible, looking for this and that and putting it together. That really isn’t an explanation. Anyway, that was sort of a question here.

Stan Carmack: Q. To your knowledge, do books like The Late War or View of the Hebrews—pseudo-Biblical texts—use any of the grammatical variants from the 15th and 16th century?

A: It is the 16th and 17th century, mainly … Early Modern English does begin at the end of the 15th century. OK, there is usage, but it pales in comparison with what we find in the Book of Mormon. For instance, there is no “the more part” usage, there is no past tense expression that is Early Modern in its orientation. And for another one, that Royal’s looked at, is a genitive of “commanded of the Lord”—very sparse, very infrequent in pseudo-Biblical texts, and quite frequent in the Book of Mormon like the Bible. So the Book of Mormon far outshines these pseudo-Biblical texts in its syntax that is archaic.

Q: Why should we consider the archaic English instead of Joseph’s hick-talk?

A. Well, I gave examples of systematic usage. So, did Joseph Smith know the “did” usage of the Book of Mormon? All independent linguists, who have nothing to say about the Book of Mormon, have said that there was no such usage in any form, in any variety of English in the 1820s: not British English; not American English. So Joseph Smith did not know that past tense expression.

Again, I showed also how with the syntax after verbs like “command”—and I could have extended it to verbs like “cause,” “suffer,” “desire”—Joseph Smith’s usage was far different from what we find in the Book of Mormon, and the Book of Mormon differs substantially from what we find in the King James Bible. But we find the structures again and again in the Early Modern period.

Q: Did I have a thesis going into this text analysis?

A: My thesis was that the Book of Mormon, when I did the first study on complementation after the verb “command,” was that it would be like the Bible. That was my hypothesis. And I found that it was very different.

Royal Skousen: I will just answer this one a lot of people want to know.

Q: Any theories as to why the Lord would inspire Joseph to translate into a form of English he was not familiar with?

A: I don’t know the answer. I don’t know why it is in Early Modern English, or mostly. There are some things we found, some phrases that were getting up in the late 1700s and 18[00s], but we have got these ones in 15[00s] and 16[00s] which it looks like they really died out. Now maybe they are in upstate New York, it is a relic dialect. I would suggest if you believe this, you ought to hunt for them, instead of just saying, “Well, they were there. They had to be there because it is in the Book of Mormon and we know Joseph Smith wrote it.” Well, that is just assuming the answer. See if you can go find it. I only know two people who are trying to find it; we are up here [indicating Stan Carmack and himself]. And we are finding some phrases. “I would call your attention,” which as far as I can tell—I did a lot of searching; I can’t find it in Early English Books Online—It looks like it is early 1800.

And I have also found evidence that it looks like the text was massaged, so there aren’t weird words. If you go get a 1500 or 1600 text and start reading it, every sentence or two you are going to find a word you don’t even know what it means. You have got to go look it up. When you read the biblical part, in Isaiah, in the Book of Mormon all of a sudden you hit “carbuncles” and “wimples” and stuff. I mean, I don’t know what these things are. You have to look them up! What is a besom? They did not even know what it was. Joseph thought it was “the bosom of destruction.” So when it is actually from the Bible it is hard. But the actual Book of Mormon text has no word that the translator, Joseph Smith, and his scribe, would not have recognized, even though they don’t understand what it really means. So that is sort of interesting. It is like it was massaged so that by the time it gets to Joseph Smith they will be able to read it off to a scribe. It is much more complicated. And my feeling is that we can pontificate about how the Lord did this. Some people want there to be a committee. Some people have said I said William Tyndale was on the committee, which I never did. I disavow anything I have ever said about a committee, because I don’t know, and talking about that just gets in the way. What we want to do is study this text, take it seriously, look at every word, every phrase, see what we can discover about it. That is what we are trying to do.

Notes

[1] The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. III: The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University Studies, 2016 (2 parts published, 4 parts to be published)).

[2] The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text, Royal Skousen, ed. (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2009).

[3] The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. I: The Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Extant Text, Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University, 2001).

[4] The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. II: The Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Entire Text in Two Parts, Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University, 2001).

[5] The Joseph Smith Papers: Revelations and Translations, Volume 3: Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon, Royal Skousen & Robin Scott Jensen, authors & eds. (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2015).

[6] The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. IV: Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon (6 parts), Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University, 2004-09).

[7] The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. V: A Complete Electronic Collation of the Book of Mormon, Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University Studies, projected for 2019).

[8] Mosiah 13:25.

[9] Stanford Carmack, “The Nature of the Nonstandard English in the Book of Mormon,” in the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Vol. III, : The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Royal Skousen, author & ed. (Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and Brigham Young University Studies, 2016 (2 parts published, 4 parts to be published)).

[10] B.H. Roberts, Defense of the Faith and the Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: The Deseret News, 1907) (hereinafter cited Defense of the Faith).

[11] B.H. Roberts, Defense of the Faith, supra note 10.