[Note: Be sure to check out the follow-up blog and podcast by clicking here.]

August 8, 2014

INTRODUCTION

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. It’s my pleasure to be here with you today and I look forward to discussing with you a rather sensitive topic in Latter-day Saint history. Yesterday, Brother Perkins gave an excellent discussion on blacks in the scriptures. Today I look forward to building upon that conversation as well as hoping to open up a few new lines of inquiries as well.

I’ve entitled this presentation, “Shouldering the Cross” and there is a reason for that that we are going to get into later on. But suffice it to say, there is a fairly long tradition of discussing the origins of the priesthood ban within the context of personal sacrifice; of a willingness to give up one’s dearest principles for what people tend to believe was doctrine or a fundamental part of the Church.[1] The subtitle is, “How to Condemn Racism While Still Calling Brigham Young a Prophet.” Obviously, we are going to be discussing both what racism is and is not and what it means to be a prophet and perhaps how we can, or perhaps should, redefine that term.

A foundational aspect of this topic is understanding what it means to enjoy White Privilege. Now, that is not something that Caucasians are typically used to thinking about, especially in Utah. The fact that a Caucasian would enjoy a level of privilege, if only because of the African- American population is so small. So, it is easy to convince ourselves that it’s a non-issue. But here is what it really ends up looking like.

Caucasians feel entitled to define what is and is not racist. We like to think, “OK this is what racism is supposed to look like. My grandfather, yeah, he was a nice guy and yea, he said some things, but he wasn’t racist because I love my grandfather.” Now one thing you need to understand about the Stevenson family is that we love ourselves. Stevensons are enamored with their past, their present, and their future. I’m fully convinced that if Stevensons were offered the opportunity to found a country of their own, they would jump at the chance and we have a national anthem ready to go. So I grew up in a culture in which we were more than proud to invite people to our family reunions because we were just that good. Right: “Come along and be a part of the Stevenson empire.”

But, there was something of a dark underbelly to the Stevenson experience and many of you may have had this similar experience in that we had a relative who entertained certain racial insensitivities. It was no secret. We all knew exactly what he believed about minority races, in particular, African-Americans. On one occasion, a good man in our family, a man who was of high stature–we all respected him–he made some comments about this relative who entertained these racial insensitivities. Now, let me it clear: we all held this relative in the highest regard. He was a well-respected man; his children turned out fantastically; he worked his fingers to the bone trying to provide for his family. He was the sort of person that we would often say tributes about in testimony meetings and family gatherings. But, one time during one of our great family reunions, I heard the comment made by the relative that I mentioned, that this racism was indefensible. It was inexcusable. There was no way to explain it away; there was no reason to sympathize with it; there was no reason to excuse it; there is no reason to try to negotiate it or engage in apologia. It was indefensible. And the man who was saying this, he was no heretic. He was no left-wing radical who was trying to fundamentally change the structure of the Church. He would never have called himself an activist; in fact, he was probably the best connected to the Church hierarchy out of everyone in our family and he had held several high level positions within the Church. So when I heard him say that about such a good man within our family, I asked myself a hard question: How could a man who is so good, so respected, so loved, be so wrong about something so important? This was a question that loomed over all of us. We all had to grapple with this relative’s racism from an early day.

It is noteworthy too, that at one point, he was taking a trip to Missouri (and, as you will see, Missouri is symbolically significant in the history of race and Mormonism). On his way to Missouri a relative said, “So would you ever want your descendants to entertain the views that you now entertain? Would want them to pass that on?” He said, “No, I would not. This ends with me.” So the idea that a person—or, I might even add, an institution—could have tremendous potential, but even at the same time have an Achilles’ heel, have a deep and abiding weakness, that wasn’t new to me. Ultimately that’s what propelled me down this path of research to understand the Latter-day Saints’ tortured and difficult history with those of African descent.

This presentation will be divided into three parts. First, We are going to talk about the history; we’re going to get into the documents. We are not going to be talking about theories. We aren’t going to talk about hypotheses. We are going to be talking about what the documents actually say. Secondly, we are going to be talking about the theology of it. How can we understand prophet-hood? How can we understand a covenant people? How can we understand racism within the context of what the gospel teaches us? And finally, we will close with praxis – what does this mean? How can we apply this knowledge in our everyday interactions with, not only those of the African-American race, but also fellow white members of the Church?

1. HISTORY

First, history. We, of course, have to first start with Joseph Smith among the Saints. It’s worth noting (and this is a scripture that you all know) that the earliest revelation on how we should treat those of other ethnicities was in 1830 in none other than the Book of Mormon: All are alike under God, both black and white, bond and free.[2] How did this teaching manifest itself within the Latter-day Saint community?

When Joseph Smith founded the Church, as we will learn, there was, and I quote, “no special rule” as it pertains to those of African descent within the Church. But, the same year that Joseph Smith founded the LDS Church is the same year that a famous abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, founded his newspaper in Boston committed to the abolition of slavery in the United States. That should tell you how hot of a topic slavery and race was in America at that time. It’s tempting and easy for us, as 21st century Americans, to conflate abolitionism with being anti-slavery. That distinction is important if you want to understand the early days of Mormonism and slavery because they are very different strains of thought. It’s one thing to be anti-slavery but it’s quite another to be an abolitionist.

When Joseph Smith released the Book of Mormon and it was clear that there was to be no exclusionary rule as pertains to those of African descent—at least among those Latter-day Saints— it was met with some ambivalence. There were some Southerners amongst the Latter-day Saint community and they had a certain amount of unease when it came to their interactions with African-Americans, but one thing that they accepted was that the Book of Mormon was in fact the word of God so they were willing to go with it. They were willing to respect what Joseph Smith had revealed to them. But there was a problem: you see, even though it was one thing to be anti-slavery and it was another to be an abolitionist, that distinction wasn’t always easily discerned amongst those who considered themselves to be pro-slavery. If you were against slavery then you wanted to end the slave trade immediately; that’s what it meant to be an abolitionist. You didn’t just want to end it gradually. You just didn’t want it to fade away or hope that God would intervene at some point. Being an abolitionist meant that you ended it today, now, no compromises. You don’t negotiate with evil; you don’t negotiate with the evil slave empire. You end it today. That was the equivalent of being what we would see astoday as an Islamic fundamentalist terrorist. That was the kind of radical thought that people tended to project onto abolitionists. Abolitionists were often associated with slave uprisings – they were the kinds of people that would supposedly sneak into slave communities and whisper words into the slaves’ ears and before you would know it you have a number of African-Americans riding the streets and killing white people. This was the kind of discourse that surrounded abolitionists.

In 1830-1831, the Saints moved to Missouri which, as many of us know, was at the time a slave state. There not being any “special rule” as pertains to the African-Americans, the Latter-day Saints were at least somewhat open to the idea of African-Americans joining the Saints in western Missouri, but local forces didn’t see it that way. When they caught wind that the local Latter-day Saints were as at least open to African-Americans as they claimed, it became the pretext for mob action. When the Saints were ousted from Jackson County in 1833 that was on the short list of the causes. There were other issues as well (the Latter-day Saints were saying some really overly-kind things in the eyes of the Missourians about the Native Americans, how they are a promised people and how Missouri is the promised land and that sort of thing) but when it came to African-Americans, they said, before you know it, these Mormons are going to be bringing African-Americans into the area, and they’re going to be marrying them, and they are going to be having offspring, and is this really the kind of society that we want to have amongst our people? The Saints were kicked out of Jackson County.

This issue of race would be a specter, a ghost, that would haunt the Latter-day Saints for several years to come and Joseph Smith knew it. He knew that, at all costs, he needed to distance himself from the label of ‘abolitionist.’ He couldn’t be seen as somebody who wanted to end slavery immediately. He couldn’t be seen as somebody who might be winking at interracial marriage; so, say whatever it takes, because the costs could be mob action if he failed to do so. In 1836, April to be exact and that month is significant, Joseph Smith releases a statement in the Messenger and Advocate. In it he endorses slavery as something that is divinely inspired and, in fact, it was a great protective agent for the Caucasian community. “After all,” he said, “do we want these degraded people coming into our society and associating with our women? No, we don’t.” Again, this was all in an effort to deflect what was happening in Missouri. He could not run the risk of being called an abolitionist. In fact, Governor Daniel Dunklin, then the Missouri governor, sent a letter to W. W. Phelps, and said, Mr. Phelps, your problems in Missouri are your problems. But, just so you know, the job to prove that you are innocent of the charge of abolitionism, that’s yours. You have a responsibility to deflect it. I can’t do anything for you because, in this republic (as he said), “vox populi, vox dei” (the voice of the people is the voice of God). So if you get called an abolitionist, Mr. Phelps, that’s your problem, not mine. Good luck.

For several years, and by several years up until 1970 or so, progressive (or at least self-styled progressive) Latter-day Saints embraced an idea that was called “The Missouri Thesis.” That is that the priesthood restriction could be dated to the Latter-day Saints persecution in Missouri. They are dealing with being called abolitionists, they needed to distance themselves from the African-American community, and, therefore, they offered to exclude African-Americans from the priesthood and from the Church. This [theory] is based in some truth. This isn’t fabricated out of whole cloth. Not long after the expulsion from Jackson County, W.W. Phelps, the editor of the Evening and Morning Star (which was the Latter-day Saint newspaper there), he said, OK, so I once told you that there was no ‘special rule’ as pertains to the African-American community, well, I was just kidding. What I meant was we won’t allow any African-Americans into our midst. We will exclude them entirely. We will essentially be a white church. (As a side note, I use the terms ‘white’ and ‘black’ because they were contemporary to the time. I fully respect and acknowledge Brother Perkins’s fantastic work on this.) Phelps, he sought to do this as a sort of boxing maneuver. This played into the thinking of many historians saying, OK, this is where we got the idea that blacks should be excluded from the Latter-day Saint community.

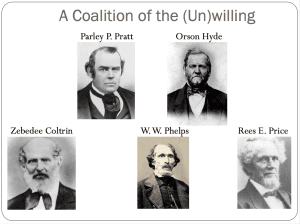

But there is a problem in that thesis. And that is that Latter-day Saint leadership came from a large coalition of thinkers. There were a variety of views when it came to issues regarding race. Let’s just go one-by-one, just to give you a sense of how different Latter-day Saints viewed those of the African-American community.

Parley P. Pratt, for example, wrote a history of the persecutions of the Latter-day Saints in Missouri in 1839 and 1840. He went out of his way to emphasize to all readers that the Latter-day Saints had such a miniscule number of African-Americans amongst their membership that it was virtually negligible. You can dismiss it entirely. We are a white church. He wanted people to understand that.

Orson Hyde made it clear to Joseph Smith that he was not comfortable with African-Americans being emancipated from slavery and being allowed into the Church as they had been.

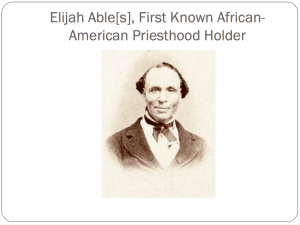

Zebedee Coltrin, he made clear his discomfort when he became acquainted with the first African-American priesthood holder, Elijah Ables.

W.W. Phelps, he had started out as something of an abolitionist, but then in 1834, he pulled a 180 and said, “Actually we want nothing to do with the African-American community,” and while in Utah, he, in fact, defended slavery.

Rees E. Price, he is the radical of the bunch; I have a certain fondness for him. He joined the faith in Cincinnati in 1842 and he was a committed, ardent, and die-hard abolitionist. In 1850 when the census was enumerated, he identified himself, as far has his profession goes, as a theocrat. I am a professional theocrat.

Then we have Elijah Ables. Who is this man? He is certainly one of the most important figures in understanding the history of the priesthood restriction though, not the only important figure. He was baptized in Cincinnati in 1832; ordained to the priesthood in 1836. We have his priesthood certificate – this is not up for debate. He served a mission to Ontario, Canada in 1838 and ordained a man to the priesthood while there and also had to dodge a tar and feather mob in the process. He returned to the main body of the Latter-day Saints, was ordained a Seventy in 1841 and then moved back to Cincinnati the following year where he served in the top level leadership of the Cincinnati branch and personally organized disciplinary hearings of white Latter-day Saints and he was listened to as well as respected. There were some issues where he was asked to primarily preach to the African-American population but that comes as no surprise to us primarily because, as we know from accounts of Joseph Smith, he often said, “Let’s send an Arab to Arabia.” Or, “Let’s send a French man to France.” He often believed that you should preach to your own ethnic group.

So the fact that Elijah Ables was ordained to the priesthood, that problematizes the Missouri thesis somewhat, because he was ordained to the priesthood within a week of Joseph Smith releasing his statement calling Blacks such horrible things and endorsing slavery. So you have Joseph Smith authorizing Elijah Ables’s ordination one week and then endorsing slavery and calling for the exclusion of Blacks entirely from their community the next.

Then we have the story of William McCary. If Elijah Ables problematizes the narrative, William McCary throws a wrench into the narrative like most of us have never seen. Who was William McCary? He was a runaway slave, also a brilliant musician, very persuasive, very charismatic, he knew how to pull in an audience, and he eventually found his way into the Latter-day Saint communities. He had a certain fondness or the Latter-day Saint communities and he often syphoned people from within the membership and created factions of his own.

He arrives in Winter’s Quarters in spring of 1847 and he promptly marries a Caucasian girl by the name of Lucy Stanton who was the daughter of a former stake president. Now, for those of you who know anything about interracial marriage and sexuality in the 19th century, this was a great example of playing with fire. William McCary, by being so willing to walk around with his white spouse, was asking for criticism at the very least. In several instances it was not was not at all uncommon for an African-American man to lose his life over such an indiscretion.

McCary makes a comment upon arriving in the Winter Quarters community and marrying his white wife. He says, of the Latter-day Saints, “Some say there go the old n—– [N-word] and his white wife” with clear disdain. People remembered Joseph Smith and they remembered that he had authorized the ordination of Elijah Ables; further, they knew that Joseph Smith had a deep and abiding affection for Elijah Ables. This was the type of friendship that endured for generations. They talked about it even long after Elijah’s death – how good of a friend Elijah was to Joseph Smith and vice versa. The Latter-day Saints remembered this and they said, “Well, Joseph Smith was OK. He’s passed on now, but we are really, really uneasy with this situation.” I provide this image for you [of the McCary quote] because that is an original image of the meeting minutes that record him saying this.

Of course, he’s immediately ostracized. The text says, “Today some of the sis[ters] said “that is the man that Bro[ther] Brigham tells his family to treat with disrespect.” So, certain members were saying, “Well, Brother McCary, yes, you found your way into our community but, just so you know, you are not welcome here.”

McCary approaches Brigham Young. He wants to see if the rumors are true. What does Brigham Young say? “It’s nothing to do with blood for of one blood [quoting Acts 17:26] has God made all flesh, we have to repent and regain what we have lost—we have one of the best Elders an African in Lowell—a barber.” He drops a few names there and comments that do call for some unpacking, but the most important aspect of this quote is he specifically endorses African-Americans holding the priesthood. Later on in the meeting, he would say, “The color of your skin doesn’t matter to us, Brother McCary. Isn’t that right, gentlemen?” Then all the other gentlemen (this is a large number of other leaders, including people such as Heber C Kimball, George Grant, other respected members of the community) they all say, “Aye, that’s true. Color doesn’t matter to us.” (March of 1847, and there is the image from which I drew that transcription:)

Mid-April, Brigham Young leaves Winter’s Quarters for the Great Basin leaving William McCary and his white wife, basically to their own devices. William McCary, in fairness, he did nothing to help the situation, because immediately (after Brigham Young leaves) he begins to marry a series of other white women, practicing his own form of interracial polygamy. You are already married to a white woman. You are already winning the disfavor of white Latter-day Saints, why not just marry a few more and see what it takes to push them over the edge. Well, he succeeded, and a white mob congregated and essentially chased McCary, as one man recalled, “to Missouri on a fast trot.” His wife Lucy followed close behind. (That [image in the corresponding slide] is not a depiction of the particular mob action; I’ve drawn this from another mob action that would have resembled what it looked like.)

How do the Latter-day Saints respond once McCary and his wife have left? Well, we know something about Parley P. Pratt’s views based on his earlier history of the persecution of the Latter-day Saints. It is Parley P. Pratt who gives us the very first evidence of the existence of a priesthood restriction. He gives it to us when Brigham Young is hundreds of miles away in the Great Basin. Latter-day Saints are pressuring Parley P. Pratt and Orson Hyde saying, “How dare you? What business do you have allowing a character like William McCary into our community? He is clearly a sexual predator. He is exactly what we would expect an African-American to be like. Here you are entertaining them. How dare you?” Parley P. Pratt says, “Well, of course that’s going to happen: he has the blood of Ham in him and those who are descended from the blood of Ham cannot hold the priesthood.” Notice what he said there: “The blood of Ham.” He didn’t say “the curse of Cain.” This is point upon which Parley P. Pratt and Brigham Young differed quite significantly. Brigham Young was insistent in later years that it was the curse of Cain. Parley P. Pratt believed it was the curse of Ham. Which is it? Already we are seeing that the foundations of the priesthood restriction are, as Sterling McMurrin said, “shot through with ambiguity.”

Brigham Young returns to Winter’s Quarters in December of 1847. He said, “This is the place,” he’s had the great experience of starting up the Mormon experiment in the West and he is coming to see how matters are. One of the first things he hears about is the William McCary incident. When Brigham Young was telling William McCary that he supported McCary’s involvement in the community (in fact he even supported McCary holding the priesthood – which he did – he had been ordained by Orson Hyde himself), Brigham Young, though, he had a line. He believed that as much as it was acceptable for McCary to be a member of the community and even as acceptable as it was for him to have a white wife, he didn’t believe that there should ever be interracial offspring. It’s one thing if two people want to get married but once you start having children, then that is something that has an impact on the human family and ultimately eternity, not to mention the priesthood.

Here is what he said. Now you’ll notice I have identified different phrases by different colors and there is a reason for that. We’ll read through the whole thing entirely:

If they were far away from the Gentiles they w[oul]d all [h]av[e]. to be killed—when they mingle it is death to all.

The first line, Brigham Young is saying that an interracial couple is worthy of death which is obviously quite violent rhetoric. It’s the kind of thing that people actually did in some communities; they made good on that rhetoric when African-Americans and Caucasians intermarried. But then he follows it up by saying,

If a black man & a white woman come to you & demand baptism, can you deny them?

So he goes from threatening death to expressing uncertainty. But then he says,

The law is their seed shall not be amalgamated [Amalgamated was a long word for basically interracial marriage – interracial sexuality]. Mulattoes [a]r[e] like mules they can[‘]t have children,

Now, this sounds like ridiculous thought in the 21st century eye, or the 21st century ear, but in the 19th century this was the thinking of some of the country’s leading scientists. One named Josiah Nott was immensely influential in helping to write up the 1850 census. He made it clear, once whites (Caucasians) and African-Americans intermarry, then you might as well just say farewell to the human race. So, Brigham Young was echoing thought that was pretty common for the time but then he followed it up with saying,

but if they will be eunuchs for the Kingdom of God’s Heaven’s sake they may have a place in the Temple.

I’ve entitled this slide “A conflicted Brigham Young” because he is a man of two minds. This incident has clearly caused him to ask some very hard questions of his own racial assumptions. He couldn’t understand exactly what to do with this. He believed in the African-Americans holding the priesthood but he simply could not abide interracial sexuality. But even at this point, he has not gone so far as to say that African-Americans should not have the priesthood; he’s still conflicted; in fact, he says, “…if they will be eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven’s sake [not have children] they may have a place in the Temple.”

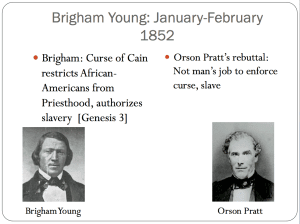

So between December of 1847 and January/February 1852, Brigham Young hardens his views on race. He gives two speeches in front the Utah Territorial Legislature and says, not only are African-Americans suffering from the curse of Cain but they are also fit for manual servitude and I therefore endorse slavery in this territory. To quote him exactly, “I am a firm believer in slavery.” He did believe that slavery should be a little bit different in Utah than it was in the South; slavery in the South was barbaric, it was exploitive. Slavery in Utah ought to be benevolent; it ought to be focused on the uplift[ing] of the African-American race but never forget that there is a racial order, he said. There are those who are superior and then there are those who are inferior. For the rest of his life, he continued to iterate these views. You never see again the comments that he made either in March of 1847 or some of the comments he made in December of 1847. He did continue to repeat his ideas that those who participated in interracial sexuality or marriage were, in fact, worthy of death. It is noteworthy that when The Act in Relation to Service (which was the slave law in Utah [Territory]), when that was passed, there was a code that that was included in it, a proviso, saying there could be no sexuality between Caucasians and Africans.

It’s worth noting that in the midst of these discussions, Brigham did not go unopposed. There was a voice who said, “Actually Brigham, I think you are wrong.” By this point, to stand up to Brigham and say, “You’re wrong,” it took somebody with a little bit of spine, a little bit of confidence and that was none other than Orson Pratt. In January of 1852, in response to Brigham Young’s first slavery speech (delivered on January 23rd), Orson Pratt said, One: it is not our job to enforce the curse that is upon African-Americans. Yes, they are cursed, we all know that; but, that’s not our business, not our problem. Two: There was no revelation on this, Brother Brigham. We’ve never heard the voice of the Lord telling us that we should endorse slavery – why are you doing it now? Brigham Young promptly follows it up by saying, Well, now that you mention this, the Lord has revealed it to me. You can find a full text of the February 1852 speech, the one in which Brigham Young says that the Lord has revealed it to me, in the second half of my book[3], including a transcription of the original Pitman shorthand and that’s actually where we get the comments from Orson Pratt. That [transcription] is thanks to the tremendous work of LaJean Carruth who is our Pitman shorthand specialist over at the Church History Library. Until she did research very recently, we had no idea that Orson Pratt had said these things.

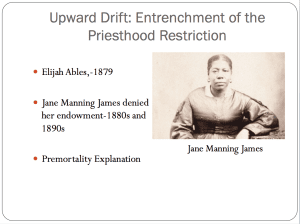

What happens from 1852 over the course of the next generation? We see that this priesthood restriction that began all the way with Parley P. Pratt, seeped into the Mormon consciousness, into Mormon society, and eventually became entrenched in the latter part of the 1870s, as well as 1880s, and 1890s. In 1879, Elijah Ables approaches the Brethren and says, “I would like to receive my endowment. I am to be a welding link between the White race and the Black race. I need my endowment.” They turned him down out-of-hand after a little bit of discussion. As far as they were concerned, they didn’t even refer to him as Elijah Ables in the minutes; they referred to him as “a man named Able” as though he was some kind of stranger, though he was no stranger. Jane Manning James, she was denied her endowment in the 1880s and 1890s.

It was around this time that the idea of a premortal explanation of the priesthood restriction came into vogue. As early as 1845, Orson Hyde had said, Yes, African-Americans were, in fact, not as valiant in the premortal life–they kind of had sympathies for the devil–but he never went so far as to say that it led to the priesthood restriction. But by now, that old line of thought was being applied to explain a priesthood restriction. So we have theology that is morphing over time. We actually see that Brigham Young, he forcefully pushed back against this thesis. He said, “Those of you that say it has something to do with premortality – it has nothing to do with premortality, nothing. It’s the curse of Cain and anyone who says otherwise is just wrong.” He was even willing to say this to his brother, Lorenzo. We are seeing that the explanations for the priesthood restriction are still fraught with ambiguity. Even amongst top Church leaders, they can’t quite decide: Is it the premortal life? Is it the curse of Cain? Is it the curse of Ham? They never went so far as to say, “We don’t really know.” but you can see this clearly in a variety of records.

2. THEOLOGY

The second part of this presentation focuses on the theology of it. What does this mean for Latter-day Saint theology?

An important aspect of the story that gets overlooked is the relationship between the prophet and the people within the covenant community. When we talk about race and the priesthood and race and Mormonism, we fixate on what Church leaders say. We look at all of the comments that they have made. We keep a catalogue and we have lists of everything that Brigham Young’s said that is offensive and racist and we rightfully get upset about it. But that’s but a small slice of the story at hand.

Prophethood is, as I argue, is bounded. The ability of a prophet to be a prophet is not without some kind of constraint. We look in [the book within the Book of Mormon called] Mormon chapter 3, verse 16: “I stand as an idle witness,” Mormon said. I can no longer preach to them righteousness.[4]

“Let not God speak with us,” the children of Israel said.[5] We only want to speak with you, Moses, and as a result they ended up receiving a lower law. And as Joseph Smith said, “The Saints… will fly to pieces like glass as soon as anything comes that is contrary to their traditions.”

There are many great and wonderful things, we would all admit, that God would love to reveal to us if we were willing to let Him. It is for this reason that I argue (let me go back to that) for a thesis of “collective responsibility.”

As we discussed earlier, the origins of the priesthood restriction were not even to be found with Brigham Young or any of the top leadership. They were at the most from Parley P. Pratt and then and only then, after he was heckled by a mob of white Latter-day Saints. As it happens, there were a number of voices who argued for a kind of collective responsibility.

We have Sterling M. McMurrin who referred to the collective conscience of guilt that a Latter-day Saint suffered for failing to uphold civil rights legislation. He called the priesthood restriction a “quirk of things past” that has endured because of Latter-day Saint complicity.

John L. Sorenson said that Church leaders had become followers of the masses; that they had experienced so much push-back from their attempts at carrying out initiatives that they realized we cannot force Latter-day Saints to be anything that they do not want to be.

Lowell L. Bennion, he said, “It might be that you and I (and all of us in the Church) because of our sins or because of our lack of thinking upon the great fundamentals that Christ taught, because of not having the Spirit of Christ, may sometimes be at fault for our limitations.”

Armand Mauss: “Perhaps the chief deterrent to a divine mandate for change is not to be found in any inadequacy among the Negroes [as he called them] but rather in the un-readiness of the Mormon Whites with our heritage of racial folklore.”

And of course, Eugene England, said, “The Lord wishes a change could be made” and that “we all bear responsibility for the fact that it hasn’t been made yet.”

The vast majority of these Latter-day Saints would not be seen as terribly conservative Latter-day Saints. They all saw themselves to be progressives and they felt it was the Latter-day Saint community that shouldered the burden.

As Edwin Woolley once said to Brigham Young (Edwin Woolley was another of those men who was willing to stand up to Brigham Young), he said, “This is my church as much as it is yours.” We use this as an anthem of empowerment but we also need to use this as an anthem of responsibility.

3. PRAXIS

Finally, what does this look in practice?

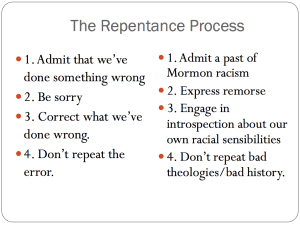

We need to repent and we all know the steps of the repentance process: admit that we’ve done something wrong; be sorry; correct what we’ve done wrong; and don’t repeat the error.

But what does this look like in terms of race?

- Admit a past of Mormon racism. That’s the first step: acknowledge that it is there and don’t pretend like it never happened because, as Brother Perkins says, we tend to be the last to recognize that.

- We need to express remorse. That’s not to say that we need to engage in a kind of self-flagellation. This doesn’t mean we need to go on the talk show circuit and constantly say, “We’re sorry. We’re sorry. We’re sorry.” Rather, acknowledge our own racial assumptions and ask what have we inherited from the pre-1978 era?

- Engage in introspection about our own racial sensibilities

- And most of all, never, ever repeat bad theologies or bad history.

That’s all; thank you.

Question and Answer Session

Q. I understand that Elijah Ables’ son and grandson were also ordained to the priesthood in the 20th century but I have never seen information on them besides their names and dates of ordination. Do we know anything else about them and their experiences?

A. I do know some things about them. Elijah’s son did have some trouble with the law. He was a bit of a teenage troublemaker. He ended up facing some charges on occasion and he had to pay a fine now and again. I have seen a picture of one of his descendants, Enoch, and he looks a bit like Mark Twain, which is noteworthy because Elijah’s family, they were kind of enshrouded in a sort of exceptionalism within Mormon society. As I found out from a descendent, when this descendent was an infant and his grandfather was holding him in arms, his grandfather said, “Ah, good, we finally got the black out of the Ables.”

—–

Q. Did Orson Hyde or Orson Pratt ordain William McCary?

A. Orson Hyde did.

—–

Q. You said that Joseph Smith endorsed slavery in 1836 but you didn’t mention that Joseph Smith campaigned for presidency on a platform to abolish slavery by selling public lands and purchasing all of the slaves.

A. That is correct. Later on during his presidential campaign he did support the ending of slavery. He was what we would call a moderate abolitionist. He wasn’t quite on board with William Lloyd Garrison but, yes, he did do that later on.

—–

Q. In your view, how does Blacks and the priesthood issue differ from the homosexuality issue of today with similar accompanying push-back?

A. I am in general reticent to mix-and-match Mormon narratives; that is my general response to that. You can find some similarities but you can also find substantial differences. The primary one being that we do, in fact, have a precedent for an African-American man holding the priesthood. We do not have a precedent for an openly homosexual, practicing man of holding the priesthood. In fact, we do have evidence for the fact that Joseph Smith strongly condemned homosexuality in no uncertain terms.

—–

Q. So it sounds like you are saying that there is no revelation on the ban but rather some experience convinced them that African-Americans should not have the priesthood, is that accurate?

A. We do not have a single document that articulates a revelation for the priesthood restriction – that is correct.

—–

Q. Brigham Young’s 1852 speech is often referred to as the original declaration on the priesthood ban. Do his thoughts tend to be presented in a political setting or are there instances where he discusses in any detail the topic in general church meetings?

A. In 1849, he mentioned it in a casual conversation with Lorenzo Snow so he was certainly articulating it before 1852 in which he gave his thoughts before the territorial legislature.

—–

Q. This question is asking about Indians who were dark skinned as Africans and they were discriminated against.

A. That is correct because we were not as focused on lineage in the 19th century Church as we are today. If you were Black it was just assumed to be that you had African blood.

—–

Q. Slavery prevalent in the North, 20,000 slaves on Long Island in 1860s, slaves treated as property…

A. I don’t understand what the question is here so I’m sorry; I’m going to have to pass over it.

—–

Q. How influential were the beliefs regarding Blacks and the seed of Cain of other Protestant groups upon the Saints as they converted to Mormonism?

A. The curse of Cain doctrine that belonged primarily to Brigham Young – he was a little bit unusual in that regard; most people accepted it being as the curse of Ham.

—–

Q. In Winter’s Quarters in 1847, when Hyde and Pratt answer that William McCary had the blood of Ham, was there any Pearl of Great Price connection to a priesthood ban?

A. They do not cite the Pearl of Great Price in their explanations, I can tell you that.

Notes

[1] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; hereafter referred to in this presentation as “the Church.”

[2] 2 Nephi 26:33

[3] For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830-2013 by Russell Stevenson see < http://gregkofford.com/products/history-of-blackmormons>

[4] Mormon 3:16

[5] Exodus 20:19