Title: Letters to a Young Mormon

Author: Adam S. Miller

Publisher: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship

Genre: Religion – Faith

Year Published: 2014

Number of Pages: 78 pages

Binding: Paperback

ISBN-10: 0842528563

ISBN-13: 978-0842528566

Price: $9.95

Reviewed by Trevor Holyoak

This is the first book in a new “Living Faith” series from the Maxwell Institute. While reading it, I struggled to determine just who the “young Mormon” is that the book is aimed at. Is it for teenagers, or perhaps for 20-somethings? I think I actually understand it much better as a 40 year old father than I would have at a younger age, mostly due to the knowledge and experience I have since gained. Then I discovered, thanks to Amazon, that there has been a whole crop recently of books entitled “Letters to a Young XXXXX” (for example, Letters to a Young Contrarian by the late atheist Christopher Hitchens). Briefly looking at some of them, it appears that this book may have been loosely modeled after them. However I still question exactly who the intended audience is.

The book covers a wide range of topics of interest to Mormons, including agency, work, sin, faith, scripture, prayer, history, science, hunger, sex, temples, and eternal life. While I did find some new insights in some of these letters, much of what is contained is vague enough that any parent who shares the book with their teenage child may want to read it themselves so they can discuss it together. The chapter on sex, in particular, warrants this, as the only thing really clear in it is an admonition to avoid pornography, and then only for some of what I consider to be the right reasons.

I asked my two teenage daughters to read a couple chapters each. My 17 year old chose the chapters on history and hunger and thought they were too vague and wished the author had connected the dots. She is probably more familiar with some of the things mentioned (but not explained) in the history letter – such as “Joseph Smith’s clandestine practice of polygamy, Brigham Young’s strong-armed experiments in theocracy, or George Albert Smith’s mental illness” (page 48) – than many young LDS people her age because I have tried to teach her about some of the more difficult topics, yet she had questions about the usage of the word “clandestine” and about George Albert Smith. In fact, with that kind of loaded wording, someone picking it up off the shelf and glancing casually at the page might get the initial impression that it is anti-Mormon material. This chapter may provide an opportunity for a parent to teach their child how to find trustworthy answers for any questions that are raised.

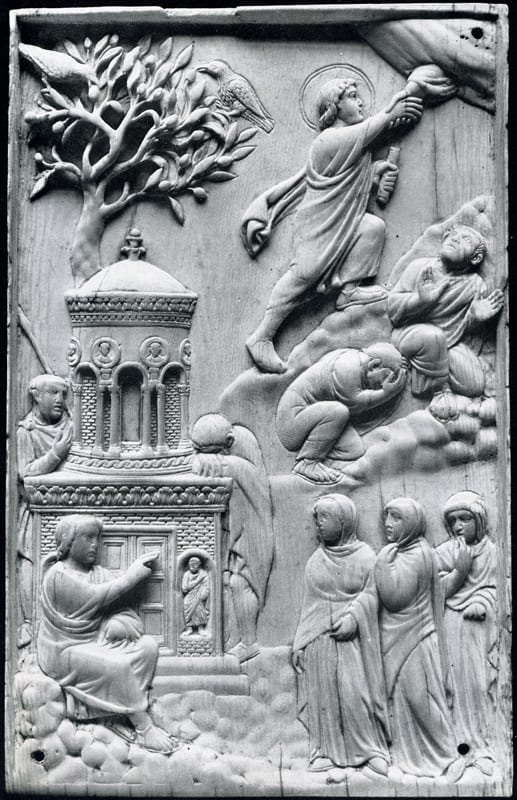

On the other hand, my 16 year old (who doesn’t like to read and appreciated the shortness of the sections) read the prayer and the temple sections, and found she could actually relate to some of it. I think the temple chapter is one of the better ones in the book, and it was particularly timely for her because the material in it complemented what I told her in a discussion we recently had after she stumbled upon a critical video on YouTube.

There are a few other places in the book where I feel good answers are given to common issues. One example is an explanation for the seemingly unscientific account of the creation found in Genesis. The author begins by explaining that the Hebrews “thought the world was basically a giant snow globe. When God wanted to reveal his hand in the creation of their world, he borrowed and repurposed the commonsense cosmology they already had. He wasn’t worried about its inaccuracies, he was worried about showing his hand at work in shaping their world as they knew it” (page 53). Miller continues through the creation sequence as the Hebrews would have understood it, and then follows up by relating his experience in changing his point of view from a literal one that he retained beyond his mission to one that allows more for the scientific explanations of today.

In regard to some of the struggles we might have when learning about church history, he points out that “it’s a false dilemma to claim that either God works through practically flawless people or God doesn’t work at all…. To demand that church leaders, past and present, show us only a mask of angelic pseudo-perfection is to deny the gospel’s most basic claim: that God’s grace works through our weakness. We need prophets, not idols” (page 47).

Where Miller is clear on things, he excels by providing much food for thought and discussion. And in spite of its weaknesses, the bright spots in this book make it a worthwhile read for people who will not be troubled by its overwhelming vagueness, although I do believe a parental advisory may be in order.