Podcast: Download (29.3MB)

Subscribe: RSS

by Zachary Wright

Introduction

For today’s introduction, I’d like to share a story from my own faith journey with you. In High School, I found myself in a dispute with a classmate who consistently challenged my faith. He didn’t believe in God, and he was very argumentative and combative regarding why he was right. I found myself thrown into a loop…it had been the first time I was forced to really consider my faith. I had deeply spiritual experiences, but those didn’t seem to answer his questions. I felt like I was on the defense, like my head was on fire. Everything I had ever believed in seemed to flip upside-down. I began poring over everything I had learned, trying desperately to find out what I could trust, and clinging to whatever truth I could find. In psychology, this is referred to as “Cognitive Dissonance,” and it’s something that critical thinkers need to be aware of in order to be successful.

Throughout this series, we’ve talked a lot about dealing with information, and processing it in a way that can help us to arrive at correct conclusions. However, lots of the data (especially about people-centered topics such as politics, history, and religion) we have comes from differing worldviews, and is loaded with differing presuppositions about life. This, naturally, will lead to some kind of conflict, because not all ideas are compatible with each other. This is further complicated by the fact that sometimes people can be closed-minded, or otherwise are unwilling/unable to accept the points you bring across. Critical thinkers need to learn how to deal with cognitive dissonance, because if you haven’t experienced cognitive dissonance yet, you will experience it eventually. It’s important to learn how to effectively navigate your ideas being challenged in a way that doesn’t make you feel miserable all the time, but also doesn’t prevent you from continuously learning. To do this, we’ll first explore what cognitive dissonance is. We’ll then look at it from a more faith-based perspective, and then, we’ll discuss how to better resolve cognitive dissonance. With our goals in mind, let’s get into it.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive Dissonance has been described as “the most influential and extensively studied theory in social psychology”(1)- and for good reason. It was termed over 60 years ago (which in terms of modern psychology, is VERY old) by a psychologist named Leon Festinger. He described it as “an antecedent condition which leads to activity oriented toward dissonance reduction just as hunger leads to activity oriented toward hunger reduction” (2). This is important to keep in mind, because unlike the common colloquial usage, cognitive dissonance is not “holding two contradictory ideas at once” (3). Instead, as Festinger indicated, it’s the mental condition that prompts us to want to reconcile conflicts in our minds.

A renowned fable may help illustrate this idea. There was a fox walking through the forest, and he stumbled across some beautiful, delicious-looking grapes. They were high up on a vine though, and so he tried jumping up and down to get them…to no avail. He tried and tried again, eventually stating to himself “They’re probably just sour grapes anyway, I shouldn’t waste my time on this” or something to that effect. He then gave up, having convinced himself to leave. This actually explains this psychological phenomenon rather well. The fox in this story was put into distress-cognitive dissonance-when he found that he was unable to get the grapes. To resolve said dissonance, he convinced himself that the grapes were sour to “justify” himself giving up.

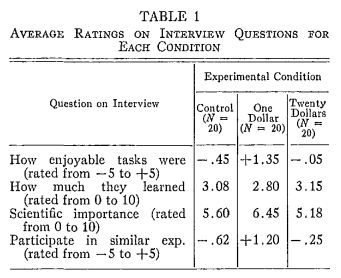

There are also some very interesting, real-world examples of this occurring as well. In a follow-up experiment, Leon Festinger once again took it upon himself to explore the concept of cognitive dissonance. He took 71 psychology students (one at a time), and had them take 12 spools, and place them into a tray using only one hand. Then, using the same hand, the students were to take all of the spools out of the tray, and repeat the process for about 30 minutes. Then, they had to do a similar exercise where they had to turn wooden pegs a quarter turn for another 30 minutes. Basically, it’s designed to be boring. At the end of the experiment, an experimenter would pull them aside, and tell the participants that they needed help convincing others how exciting the experiment was. To one group of students, the experimenters offered $20, to another group, they offered $1, and to another group of students, they offered no compensation. Take a moment to guess which group reported the highest satisfaction with the experiment. If you guessed the group that was offered $20 gave the best report of the boring experiment, I don’t blame you. Interestingly enough, that’s not what happened. Instead, the group that was offered $1 rated the experiment most positively.

So, what happened? Well, in the analysis, they explained the following.

1. If a person is induced to do or say something which is contrary to his private opinion, there will be a tendency for him to change his opinion so as to bring it into correspondence with what he has done or said.

2. The larger the pressure used to elicit the overt behavior (beyond the minimum needed to elicit it) the weaker will be the above mentioned tendency. (4)

Put another way, the conclusion arrived at was that the participants changed how they viewed the experiment and that the participants who were most heavily rewarded were less likely to change their behavior. This makes sense…the students who got rewarded $20 (an amount that was far larger back in the 60s) didn’t need to change their opinion. They were already compensated for their time, and the dissonance has been resolved. However, those who only received one dollar didn’t get that satisfaction, so they had to resolve it a different way. This is the crux of what cognitive dissonance is.

However, this still leaves us with questions like “What do you feel when you experience cognitive dissonance?” or “What specifically can cause cognitive dissonance?” Some writers indicate that a person suffering from cognitive dissonance experiences “anxiety, embarrassment, regret, sadness, shame, and regret” (5). Some causes for cognitive dissonance include being forced to do something you believe is wrong, making decisions based on options that don’t seem appealing, or giving in to addictions (6). Again, all of this goes back to the idea that something prompts us to feel “bad” about something that is happening that goes against what we believe, or challenges the presuppositions that we have.

Dissonance in Faith Contexts

Religious discussion, like many other topics, can prompt cognitive dissonance. The example I used in the introduction is one of many stories wherein cognitive dissonance played a role in my behaviors and actions. One author doing a qualitative study on the feelings behind these “faith crises” in Christianity noted the following:

In the words of Durà-Vilà and Dein (2009), a Christian is susceptible to a period referred to as the, “Dark Night of the Soul,” which is described as a “loneliness and desolation in one’s life associated with a crisis of faith or profound spiritual concerns” (p. 544). This crisis of faith can cause great suffering and emotional distress and can even resemble symptoms of a depressive episode (e.g., feelings of guilt, loss of interest, anxiety). Efforts to participate in spiritual activities such as prayer, attending church, or fellowship with other believers can feel overwhelmingly difficult. Additionally, these spiritual practices can lack the meaning they once held for the believer. These crises of faith can be short-term, or last years, and can potentially become as severe as an individual abandoning his or her faith altogether. (7)

Those feelings sound familiar, don’t they? Basically, the argument being made is that those who are experiencing these feelings are having what many have called a “crisis of faith,” which prompts them to make decisions to resolve the negative feelings. These “Faith Crises” are often described by both members and former members as being among the most difficult parts of their lives. Remember, when someone begins to question the nature of their faith, they’re questioning the very nature of reality as we understand it. The negative feelings that come along with such questions are very real, and should not be ignored.

As we’ve learned though, those feelings are only part of the story, seeing as how cognitive dissonance is manifested not by the feelings alone, but also how people set out to “resolve” those feelings. Many members of the church who experience a “faith crisis” may have questions about whether or not Joseph Smith was a prophet, and so they might peruse the Joseph Smith Papers to help gain insight into who Joseph Smith truly was. Others may have questions about whether or not God exists, and so they turn to the scriptures (as well as other sources), and ponder whether or not God exists. Others may even choose to leave the church, believing that the reasons to believe in the church’s truth claims are unsatisfactory. As you can see, when the dust settled in terms of my faith journey, I did not come to the conclusion that the church was false. Even so, the final option of abandoning organized religion seems to be one that many people (especially in my generation) seem to be embracing. (8)

It’s worth noting from a cultural perspective though that some people have issues calling this a “faith crisis.” Critics of the church might be more prone to blame the church and not their own faith, and members of the church sometimes get self-conscious at the prospect of losing faith. Instead, members of the church want to structure this as more of a “faith remodeling” focused on questions as opposed to some kind of crisis. (9) I can get behind this rhetoric, as I believe that asking questions about our own faith and restructuring it seems like a good practice to me. However, having been acquainted with my own feelings, and the feelings of others, of people navigating these issues, I also have no issue talking about it in terms of the strong emotions involved. Regardless of how you view it, the relationship between cognitive dissonance and the feelings associated with what many people call a “faith crisis” is worth analyzing.

Resolving the Dissonance

With such powerful emotions at play, it almost goes without saying that this topic should be taken seriously. There are a few things that people can do to resolve the dissonance. For example, psychologists suggest that cognitive dissonance is resolved in a few different ways, including:

- Changing our behavior so that it is consistent with what we’ve learned.

- Changing one of the dissonant thoughts in order to restore consistency.

- Adding other (consonant) thoughts that justify or reduce the importance of one thought and therefore diminish the inconsistency.

- Trivializing the inconsistency altogether, making it less important and less relevant. (10)

I think that breaking down the issue in this way is useful. Objectively, we need to do some kind of reorganization of our thoughts, whether by adding to, changing, or ultimately changing the authority of those thoughts. For example, I’ve made it clear that I don’t like raw tomatoes. If I’m forced to eat raw tomatoes, I can resolve the ensuing cognitive dissonance by either:

- Just choose not to eat the tomato

- Try to convince myself that the tomato is actually good

- Adding a thought as to why I’m eating the tomato (perhaps I’m being paid to do it, or I don’t want to hurt the person’s feelings

- Or I just dismiss the thought that I don’t like tomatoes, and choke them down anyways.

Now, addressing cognitive dissonance from that perspective is certainly not a bad approach. However, that still leaves us with the more practical question of “How can I help my friend or loved one”? You can tell them to change how they’re thinking or feeling, but that alone probably won’t do much good. As will soon be shown, a careful application of critical thinking in combination with spiritual direction can allow us to connect to those who are struggling in ways that are meaningful and effective. Specifically, Latter-day Saints should understand and care about this topic so they can empathize with those experiencing a faith crisis, help them identify what the root of their faith crisis is, and eventually help them recognize that the feelings they have are a natural part of a healthy, progressing, and ultimately fulfilling faith.

While a technical psychological definition is still up for debate, empathy is usually characterized by “a complex capability enabling individuals to understand and feel the emotional states of others, resulting in compassionate behavior.” (11) While it does not necessarily mean that you embody the anxiety, anger, or sadness that may arise during these crises, it does mean that you are emotionally present and that you are able to perceive the emotions that others are feeling accurately. (12) Consider the following commentary stated during the Annual Seminary and Institute Training and Institute Broadcast:

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. Genuine empathy brings people together; it sparks connections and helps people feel they are not alone. It is a critical part of creating a sense of belonging. This attribute is a key to responding effectively to a student with a question and to effectively leading a group discussion where many students listen carefully with unspoken questions. (13)

An important aspect of empathy includes asking questions, and genuinely listening to people. We’ve discussed the importance of asking questions in terms of critical thinking, but getting to the root of what a person actually feels requires careful questions, and patient effort. Not only are you able to get to the root of what a person is feeling, but you in turn get to figure out exactly what a person is truly concerned about. Put another way, by figuring out what they are feeling, you figure out what they truly care about. In the last episode, I alluded to the idea that many people leave the church not because of historical issues or doctrinal issues themselves. Rather, they leave because of the feelings that are brought about by these issues. If you can address the feelings, you can figure out more how to help resolve the dissonance.

And that brings us to another very important facet to this conversation: Cognitive dissonance is not necessarily a bad thing. I’ve changed how I view cognitive dissonance (see what I did there?) in such a way that I now look at it as evidence of learning, and an opportunity to grow and develop my ideas. This is true in just about every aspect of life, but it’s especially important to remember when we talk about faith. I find experiences that we refer to as “faith crises” often work in a similar way. We find something that prompts questions and challenges us, and it prompts us to learn more about the gospel of Jesus Christ, or the history of the restored church, and it can provide us an opportunity to cling onto the peace that is found with the Savior. When we embody this pursuit of truth inherent within LDS theology, this aspect of critical thinking comes very naturally, and we should make full use of that advantage. Although it’s difficult to navigate the complexities of cognitive dissonance, connecting with trusted sources, open communication, continual learning, and consistent connection with our Heavenly Father resolves cognitive dissonance far better than anything else I’ve found.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cognitive dissonance is an important and recurring aspect of our journey to become critical thinkers. It has a long history, and pertains to many different contexts of our lives, including our identities as children of God. Even so, there are a few options at our disposal that can help us, and others, navigate the complexities of cognitive dissonance. Whether we are actively regulating our thoughts and opinions in a manner that is conducive to critical thinking, or we’re helping others by being empathetic, or even just becoming more comfortable with the complexities of life, cognitive dissonance does not need to be a stumbling block in our lives. If we’re able to navigate those feelings well, we’re all that much closer to becoming the kinds of thinkers, and believers that God wants us to be.

References:

- Alfnes F., Yue C., Jensen H. H. (2010). Cognitive dissonance as a means of reducing hypothetical bias. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 37, 147–163; Cited in Perlovsky L. (2013). A challenge to human evolution-cognitive dissonance. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00179; This article also references the “Fox and the Sour Grapes” story, which likewise originates from one of Aesop’s Fables.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hive-mind/202002/dissonant-cognitions

- Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive dissonance. J. Abnor. Soc. Psychol, 58, 203-210.

- https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-cognitive-dissonance-2795012

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326738, see also https://health.clevelandclinic.org/cognitive-dissonance/

- https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/7462/WEBB-MASTERSTHESIS-2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://inallthings.org/why-theyre-leaving-and-why-it-matters-gen-zs-mass-exodus-from-church/

- https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/inspiration/questions-of-faith-not-a-crisis-of-faith?lang=eng

- https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-dissonance-theory/

- Riess H. (2017). The Science of Empathy. Journal of patient experience, 4(2), 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373517699267

- Spreng, R. N., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of personality assessment, 91(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381

- https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/broadcasts/auxiliary-training/2021/01/11webb?lang=eng&id=p15#p15

Further Study:

“On Dealing with Uncertainty” by Bruce C. Hafen, link here

“Faith is Not Blind” by Bruce C. and Marie K. Hafen, link here

“Questions of Faith, Not a Crisis of Faith” by Molly Ogden Welch, link here

Zachary Wright was born in American Fork, UT. He served his mission speaking Spanish in North Carolina and the Dominican Republic. He currently attends BYU studying psychology, but loves writing, and studying LDS theology and history. His biggest desire is to help other people bring them closer to each other, and ultimately bring people closer to God.

Zachary Wright was born in American Fork, UT. He served his mission speaking Spanish in North Carolina and the Dominican Republic. He currently attends BYU studying psychology, but loves writing, and studying LDS theology and history. His biggest desire is to help other people bring them closer to each other, and ultimately bring people closer to God.