Podcast: Download (39.9MB)

Subscribe: RSS

by Zachary Wright

Introduction

In my life, I’ve found that everyone has a specific philosophy that they live by, whether they realize it or not. Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to the philosophical branch of epistemology. Epistemology, while sounding complicated and boring to some, is just the fancy way of saying “the study of knowledge.” Consider the following:

Epistemology is the theory of knowledge. It is concerned with the mind’s relation to reality. What is it for this relation to be one of knowledge? Do we know things? And if we do, how and when do we know things? These questions, and so the field of epistemology, is as old as philosophy itself. (1)

As we can see, this is a pretty deep topic, and I doubt I could cover everything about epistemology in this article. For example, a branch of epistemology touches on whether or not it’s even possible to know anything, and we’re not going to be getting into that. However, we will be going over the branch of epistemology that covers “how do we know what we know,” or in other words, “where do we learn what we know.” Why does this matter? Critical thinkers need to establish an epistemology so that they can develop levels of confidence about the validity of certain information. With that confidence, it becomes easier for us to make decisions in light of the evidence, and solve problems. In this article, we’re going to be explaining some terms, then go over some sources from which we can learn, and then explore how these concepts can relate to LDS theology. Hopefully, that will help explain this complex issue in a useful way.

Knowledge & Certainty

Now, a brief definition of terms is warranted here. Knowledge is a tricky thing to define, and there is a lot of discussion about how every epistemology fails to account for something at some point (2). However, this does not mean that all epistemologies are created equal, and there are good ways to establish confidence about an idea regardless. For this article, when I use the term “knowledge,” I’m going to be borrowing from philosophy professor Michael Huemer’s definition of it as outlined in his book Understanding Knowledge. Michael Huemer suggests that there are four things that we need to have knowledge, which is referred to as the “defeasibility theory of knowledge.” It’s outlined in his book in the following way:

- Belief: You have to believe that it’s true

- Truth: it must agree with reality

- Justification: there has to be a reason for you to believe it

- There can’t be any proposition that, if added, would remove the justification for believing it (3)

This model, as with all models, has some presuppositions. It presupposes that objective truth exists, and that it is indeed knowable through specific processes. (Whether or not it does exist is another discussion; but to be fair, claiming the opposite would in itself be a claim of objective truth, so denying objective truth is a self-defeating proposition, and in my opinion, should be avoided.) In short though, at least for this article, knowledge is an idea/conceptualization of something that meets those four criteria. Otherwise, at least from this perspective, that idea is only classified as a belief, and not necessarily knowledge.

Now, this is where things get tricky because according to this model, knowledge is differentiated from certainty. There are a few kinds of certainty defined by philosophers out there, but I’m mostly going off of the idea of “absolute certainty:” that is, the idea that we can know something without any kind of doubt whatsoever. Absolute certainty, as I see it, implies the idea that we are 100% confident that something is true. However, we can’t be 100% certain about anything, because even if we were to identify a way for us to be 100% certain about something, it would by necessity employ circular reasoning of some kind (4). Consider this illustrative argument:

P1: X Method teaches us how to be 100% certain about something

P2: This argument follows X Method

Conclusion: We can be 100% certain that X Method works

The problem there is apparent: the argument presupposes that X Method is true, and begs the question why it is true. It’s the same thing as saying “We can be 100% certain of X Method because X Method states we can be 100% certain of X Method”, an argument we recognize as fallacious. It’s worth noting too that absolute certainty is often associated with “psychological certainty”, and it can be had about beliefs just as much as it can be had about knowledge. Consider the following:

Psychological certainty, for its part, is generally regarded as being non-factive. For example, John can be psychologically certain that it is raining in Paris even if it is not raining in Paris. In addition, psychological certainty does not require that a subject be in a favorable epistemic position. John can have no reason to believe that it is raining in Paris, and yet, be psychologically certain that it is raining in Paris. (5)

In other words, the confidence we feel about something provides no strength to our ideas. With this in mind, absolute certainty is as worthless as it is impossible to obtain. So, does that mean that we can’t have any confidence about anything? Well, no, it just means that we can’t be 100% certain about anything. This doesn’t mean that we can’t develop confidence in an idea at all. The goal of epistemology is to provide a system of learning that can help us be confident about our ideas, an “epistemic certainty” if you will (6). It is for this reason that I and others have no problem saying statements like “I know the church is true” when we bear our testimonies. We’re not saying that we have absolute certainty that the church is true: rather, we’re saying that we have a high degree of confidence (due to the Spirit) that the church is true and that our testimonies are based on the prerequisites for “knowledge” described above.

The Umbrella Model

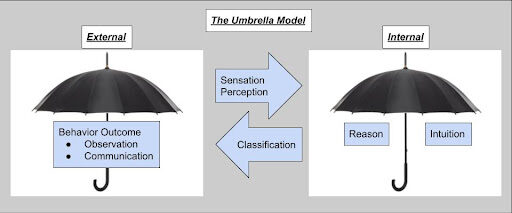

When we “Learn” something, I’m referring to two kinds of processes by which a piece of information ends up in our brain. The first kind of learning comes from a more concrete psychological perspective, where learning is characterized by terms such as Classical Conditioning, Operant Conditioning, and Observational Learning. Using sensations and perceptions, we’re able to receive signals from the outside world and translate them into thoughts (7). Those thoughts are then put into our brains, and we have them at our disposal (though the mechanism by which this occurs is still lost on neuroscientists and psychologists). The second form of learning is more abstract and has to do with consciously or unconsciously processing the information we’ve taken in (8). I mention this because I classify my epistemology as being under these two umbrella categories: internal to the mind, and external to the mind. Consider the following diagram.

This is a diagram of epistemology that I think suits the purposes and needs of all people, including LDS critical thinkers.

Under the external umbrella, I’ve allocated each of the things that I reserve as being primarily focused outside of the self. In other words, this is the umbrella where we have outside information being put into our minds. Behavioral consequences or outcomes, for instance, happen outside of the body, and must be observed (and I have yet to find other things to put under this umbrella, as you’ll soon see). When I use the term “observe” or “observation,” I’m not just referring to using your eyes; rather, I’m referring to the full spectrum of sensation and perception. For example, if I were to take a bite of an apple, that’s an outcome of a behavior that I would observe and internalize through sensation/perception (9). It’s worth noting that the scientific method falls into this sub-category. Some basic examples of this include the following:

- We look in the sky and see a bird flapping its wings. We observe the outcome of that behavior: that bird can fly.

- I reach my hand out and accidentally touch a hot stove. I observe the outcome of that behavior: my hand gets burned.

- We, against our better judgment, bite into a raw tomato. We observe the outcome of that behavior: That tomato tastes terrible.

In the same realm as behavior outcome, we have communication or testimony. Communication is unique among behavior outcomes in the sense that it is the only way for us to understand ideas that other people have in their minds, and the only way for others to understand the ideas in our minds (10). Some basic examples of this include the following:

- My mom tells me she loves me. I observed the outcome of that behavior: I now have the idea communicated to me that my mother loves me

- Someone scrunches up their face, furrows their eyebrows, and is yelling. I observe the outcome of that behavior: I have the idea communicated to me that they’re upset.

- My sister hugs me. I observed the outcome of that behavior: I now have the idea communicated to me that she cares about me.

As you can see, with communication, there is a bit of clarification that needs to happen, and a bit of cultural background and knowledge is required. However, I wouldn’t put it outside of the external umbrella, as it is still very clearly the result of behavior outside of yourself. However, that specific behavior seems to be subject to more complex, internal processes (more on that in a moment).

As for the internal methods of having ideas put into our minds, we turn to both the processes of reasoning and intuition. The internal umbrella is characterized by our brains processing or adding information in our minds, (mostly) independent from their surroundings. This is where I place Reason and Intuition as epistemic sources. Now, I’ve already done two articles that explore logic, logical fallacies, and reasoning, so I won’t go into too much detail here. However, suffice it to say that reason is the process of arriving at specific conclusions based on specific premises, analyzing the strength of ideas to arrive at new ideas. An additional note I will add here is that these premises can be arrived at by any source of information, but reason allows us to arrive at new conclusions/ideas. Intuition though is a bit harder to explain, and it has a kind of slippery definition. Roughly speaking, it’s all the ideas that arrive in our head that don’t come from conscious reasoning (11). Consider the following characterization of intuition, and how it differs from Insight:

Based on these examples, both phenomena – intuition and insight – may be conceived of as non-analytical thought processes that result in certain behavior that is not based on an exclusively deliberate and stepwise search for a solution. Non-analytical thought means a thought process in which no deliberate deduction takes place: individuals are not engaged in the consecutive testing of the obvious and/or typical routes to solutions that define deliberate analysis. Instead, intuitions are characterized by the decision maker feeling out the solution without an available, tangible explanation for it; insights are characterized by the fact that the solution suddenly and unexpectedly pops into the mind of the decision maker or problem solver being instantaneously self-evident. (12)

There is a bit of debate as to where intuition comes from, but its ability to recognize patterns, its overall efficiency, and its impact on morality are all worth noting (13). Some basic examples of intuition include the following:

- A surge of nervousness rushes through you as you enter a dangerous situation. You know that you’re in danger.

- You make a decision quickly, but can’t explain why. It just “felt” right.

- You have a feeling in your ‘gut’ that you should listen to the missionaries and what they have to say.

As you look at the chart, there seems to be some kind of connection between each of the sources of information. Intuition and Reason seem to rely on outside information often to recognize patterns, establish arguments, and arrive at conclusions/ideas. Consequently, we see Intuition and Reason classify certain events a certain way, manipulating the authority they have as being stronger or weaker, thus affecting how we learn from external sources. I can cite an example of this concerning a historical figure in the church.

Those familiar with LDS history are familiar with the figure John C. Bennett. Bennett was a friend to Joseph Smith and the mayor of Nauvoo for a brief period. However, Bennett was cut off when Joseph found out that, among other things, Bennett was using his position (as well as rumors of plural marriage in Nauvoo) to trick women into sleeping with him (14). From that point on, Bennett became a bitter, hostile critic of the church, making all kinds of claims against Joseph Smith and the saints (with varying degrees of veracity). Here’s how one author described Bennett’s allegations against Joseph.

Bennett was touring the nation with a lurid, book-length exposé, charging Mormon leaders with “infidelity, deism, atheism; lying deception, blasphemy; debauchery, lasciviousness, bestiality; madness, fraud, plunder; larceny, burglary, robbery, perjury; fornication, adultery, rape, incest; arson, treason, and murder.” He said Smith and his followers “out-heroded Herod, and out-deviled the devil, slandered God Almighty, Jesus Christ, and the holy angels, and even the devil himself.”(15)

That’s quite the list of allegations, and the critical thinker will rightfully begin to question whether or not those claims are legitimate. Some people think so, others not (myself included), but that debate in and of itself isn’t the issue. The point I’m trying to make is that when we as critical thinkers read things like that, we are aware that our internal reasoning, or our intuition about Joseph Smith, affects how we view John C. Bennett. Perhaps intuition suggests that Bennett may be acting out of rage, or perhaps we reason that there’s more going on in the story. Whatever the case may be, our internal processes affect how we interpret external sources. More on that in a moment.

This explores another important facet of epistemology: that is, that epistemology shifts somewhat depending on the topic. I’m not saying that it changes without any standard; rather, I’m saying that outcomes of behaviors (both communication and otherwise), intuition, and reason all play different roles in different scenarios, and that what we give priority to needs to shift to be effective. Why is that? Because we only have so much information to work with for a given topic! For example, as in math, reason may be more helpful than communication in some scenarios. There are only so many people who talk about math, and the conceptualization of math is a purely internal, reason-based process done in our minds. For historical analysis, while reason may be useful, communication is often more important when it comes to arriving at conclusions. Communication provides more (hopefully accurate) details about past events, and the thought processes of the people who lived through them than reason does. As critical thinkers, we need to apply the right sources of information for the right kind of job…and this is especially true when it comes to religious belief.

Epistemic Regress and the Spirit

This is where things get tricky though, because we begin running into a problem. While the external umbrella sources are vital, most of the brunt work done in epistemology is done under the internal umbrella sources. It doesn’t matter how many testimonies or behavior outcomes exist around somebody, if the internal sources are in charge of processing the information, they ultimately have epistemic superiority over the sources in the external umbrella. But let’s say that we’re analyzing a complex topic such as “morality”…which one is better: Reason or Intuition? One may initially suppose that “reason” is the ultimate source. However, we run into a problem there because reason requires an infinite number of premises to be acknowledged valid. Consider the following:

Arguments are our model for how these reasons go–we offer some premises and show how they support a conclusion. Of course, arbitrary premises won’t do, so you’ve got to have some reason for holding them as opposed to some others. Every premise, then, is a conclusion in need of an argument, and for arguments to be acceptable, we’ve got to do due diligence on the premises. This, however, leads to a disturbing pattern–for every premise we turn into a conclusion, we end up with at least one other premise in need of another argument. Pretty soon, even the simplest arguments are going to get very, very complicated. (16)

This dilemma is referred to by philosophers as the epistemic regress problem. However, before we can more fully explore the implications of epistemic regress, we have to explore some of the ways people have tried to solve it.

There are a few philosophical systems out there that attempt to resolve the problem (epistemic foundationalism, coherentism, infinitism, etc.). While there are notable differences between them, there is good evidence to support that they all derive their strength from a singular principle: metaphysical grounding (17). Metaphysical grounding tackles the question of “what grounds what,” or “what is the foundation or basis of something” (18). Consider the following:

Metaphysical ground is supposed to be a distinctive metaphysical kind of determination. It is or underwrites constitutive explanations. These explanations answer questions asking in virtue of what something is so. For example, suppose that an act is pious just in case it is loved by the gods. Following Socrates, one might still ask whether an act is pious because the gods love it or whether it is loved by the gods because it is pious. This may be interpreted as a question of ground. (19)

In other words, epistemologists seem to converge on the idea that the true basis of something is grounded on a fundamental principle (either that or they just embrace skepticism). After all, how can we expect to learn about topics like morality if we can’t identify the sources by which things like morality are learned from? However, that leads us back to our question: What is the ultimate source of knowledge about something like morality? What’s the foundation of morality? This is where I think Christianity, and specifically the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, really begins to shine.

As members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we believe that the foundation of everything good comes from God (20). We also believe that every person is given the ability to discern what is right and wrong through the Light of Christ, which is described as being “in all things” (21). This is where I believe that our moral intuitions come from (at least in part), though as we mentioned earlier, intuitions are affected by other aspects of our surroundings all the time. I see the Light of Christ and the Holy Ghost interacting with the above-outlined epistemology in a few different ways:

- It suggests that the light of Christ is interwoven within every one of the sources of epistemology (though it’s arguably manifested most through intuition), helping us classify things as being morally “right” and “wrong”

- The Holy Ghost uses these sources together to testify of Jesus Christ and to help us believe that he is the Savior and Redeemer of the world.

- By enhancing our understanding of these sources, it becomes easier for us to recognize the Light of Christ and the Holy Ghost in the natural world.

This has all kinds of fascinating implications for what we find above. If this is how the Light of Christ/Holy Ghost works, what does that imply for our souls? Do they interact with intuition in a similar way to help us choose? Or is there more than meets the eye? As it stands, it’s impossible to say, but this umbrella model of understanding epistemology accommodates LDS theology rather well.

Now, there is one more thing that I’ll mention here, and it has to do with the grounding example found above. Many people wonder whether something (let’s call it X) is good because God does X; or whether God does X because it is good. Other people phrase the question in terms of “is God subject to laws, or does God make the laws?” I find such discussions somewhat pointless (being a rather practical person), and a part of me thinks it’s a distinction without a difference. There is room in LDS theology for people to disagree on this issue. Regardless of your opinion, the point remains: by grounding our moral epistemologies on God, we claim that we can learn about an objective moral standard and that through a relationship with him, we will continue to learn more about that standard. Either way, God helps you gain access to that information. A belief in God also helps add insight to a centuries-old philosophical problem, which is always a plus.

Conclusion

In conclusion, epistemology is an important topic with a complex history. I hope that by discussing this topic, critical thinkers can be more equipped to answer questions and recognize where they’re getting their information from. By doing so, critical thinkers can arrive at better conclusions more often. LDS critical thinkers can also benefit from these ideas by being able to answer questions like “Do I know the church is true?” or “What are the sources of truth I can rely on?” We all have a lot to gain from studying epistemology, and I hope that by educating people about it, we can make a positive difference in the world.

References:

- https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/philosophy/research/themes/epistemology

- Huemer, M. (2022). Understanding Knowledge. M Huemer.

- Ibid

- With this statement, I’m referring to a certainty that isn’t the philosophical concept of “objective certainty” or “propositional certainty”. Objective certainty states that something MUST be true given the premises (this relates to deductive reasoning, which I’ve discussed here). However, I’m referring to ideas outside of this realm of certainty…the realm that deals with history, theology, and the vast majority of human experience.

- https://iep.utm.edu/certainty/

- Reed, Baron, “Certainty”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/certainty/>.

- Myers, D. G., & DeWall, C. N. (2020). Psychology (13th ed.). Worth Publishers. It’s worth noting that this is where many psychologists arrive at the realm of determinism. If all behavior is just X action + Y Environment → Sensation/Perception → Z result, then it becomes easy to believe in determinism. For a deeper dive into how this psychological view contrasts with LDS Theology, I recommend this article here (noting a more negative view of Determinism from a psychological perspective). For a more favorable view of (soft-)determinism concerning LDS theology, I recommend Tarik D. LaCour’s content here.

- https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/public-education/brain-basics/brain-basics-know-your-brain; The National Institute of Health does an excellent job in outlining the consensus of what psychologists and neuroscientists have determined is associated with brain function (they associate “reason” with the electrical signals fired in the Frontal Lobe). However, and you’ll find this universally, very few if any of the medical and psychological studies on the brain can explain why human brains “reason”. Determinism is the closest thing I’ve been able to find to an explanation, but as you can imagine, this prompts the question as to whether or not concepts such as “reason” or “moral responsibility” are possible to begin with.

- https://opened.cuny.edu/courseware/lesson/34/overview

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/some-assembly-required/201702/the-4-primary-principles-communication; This explores some principles behind communication as a way to transfer ideas/information.

- https://dictionary.apa.org/intuition, note though that a growing body of literature is starting to reject the dichotomy between intuition and reason, such as this resource here

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5020639/

- https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august-2022-fair-conference/moral-intuitions-and-persuasion; https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/201912/8-truths-about-intuition; Note how both of these sources talk about how our moral intuitions shift over time according to our experiences, upbringing, etc.

- Hales, S. A., Goldberg, J., Larson, M. L., Maki, E. P., Harper, S. C., & Farnes, S. (2018). Saints: The story of the church of jesus christ in the latter days. (L. S. Edgington & N. N. Waite, Eds.) (Vol. 1). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.; see also Bushman, R. L., & Woodworth, J. (2007). Joseph Smith: Rough stone rolling. Vintage Books.

- Ulrich, L. T. (2017). A house full of females: Family and faith in 19th-century Mormon Diaries (First). Alfred A. Knopf.

- Aikin, S. F. (2010). Epistemology and the regress problem. Routledge.

- Siscoe, R.W. Grounding and the Epistemic Regress Problem. Erkenn (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-022-00561-7

- Bliss, Ricki and Kelly Trogdon, “Metaphysical Grounding”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/grounding/>.

- https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780195396577/obo-9780195396577-0389.xml

- Moroni 7:12

- D&C 88:13

Further Study:

- https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august-2023; Steve Densley discusses how we can understand “knowledge”, and explores how we can “prove that the church is true. It’s the very last talk of the very last session of the Fair Conference, and you can find it for free at this link (you’ll need to create an account first though)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=23yprWj_yAI; Jeffrey Thayne is an LDS psychologist who does an excellent job outlining how our moral intuitions are affected by our surroundings, and what the implications are for this are for LDS theology and practice. I cited him above, but I recommend him here too.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5wCVhhzmSlU; Another video you can use to study up on some of the issues found in epistemology. Very neutral philosophy channel in general.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vo484enDccA; This is another introduction to epistemology, and Huemer’s book. It’s pretty good, and I appreciated how it was explained here (this guy is an atheist, but tends to be pretty fair)

Zachary Wright was born in American Fork, UT. He served his mission speaking Spanish in North Carolina and the Dominican Republic. He currently attends BYU studying psychology, but loves writing, and studying LDS theology and history. His biggest desire is to help other people bring them closer to each other, and ultimately bring people closer to God.

Zachary Wright was born in American Fork, UT. He served his mission speaking Spanish in North Carolina and the Dominican Republic. He currently attends BYU studying psychology, but loves writing, and studying LDS theology and history. His biggest desire is to help other people bring them closer to each other, and ultimately bring people closer to God.