Podcast: Download (11.6MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Post 1 | Post 2 | Post 3 | Post 4 | Post 5 | Post 6 | Post 7 | Post 8 | Post 9

Post 7 of 9

by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

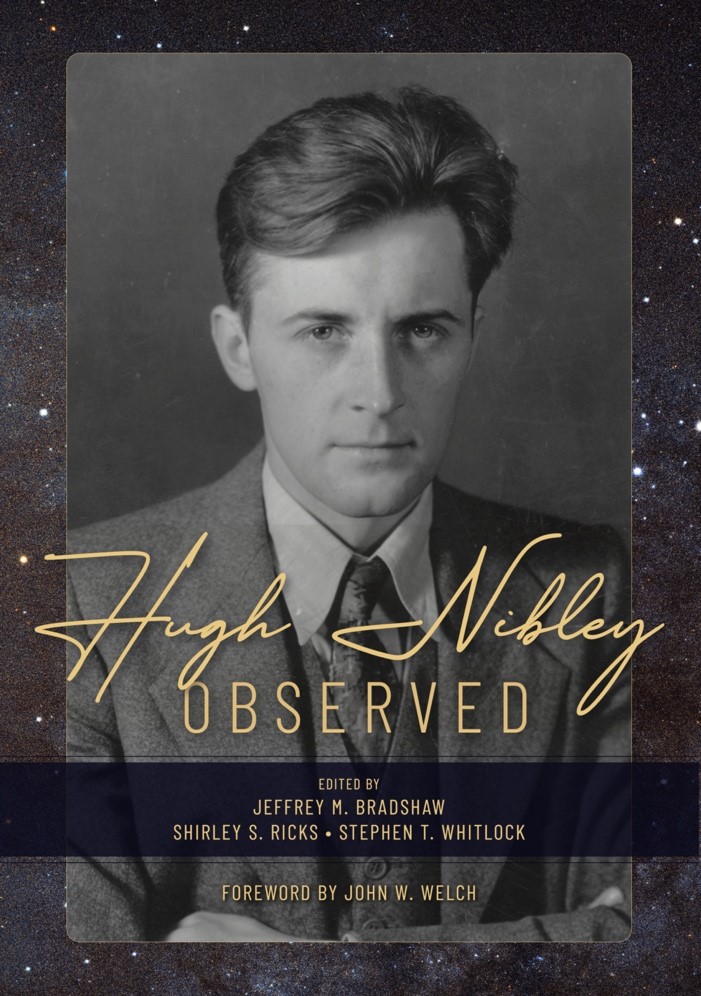

This is the seventh of nine weekly blog posts published in honor of the life and work of Hugh Nibley (1910–2005). The series is in honor of the new, landmark book, Hugh Nibley Observed, available in softcover, hardback, digital, and audio editions. Each week our post is accompanied by interviews and insights in pdf, audio, and video formats. (See the links at the end of this post.)

War

In Alex Nibley’s superb documentary history of his father’s wartime years, he shares Hugh’s account of his departure from Claremont Colleges. Having enjoyed a good relationship as a professor with the university president, Hugh rued the arrival of the new pharaoh[3] after the president died: “He didn’t like Mormons. He said, ‘You know, you are not one of us.’ I could feel the tension growing, so I left. I said, well this certainly justifies me in pursuing a patriotic duty.”[4] Elsewhere Alex continues the story:[5]

He was thirty-two years old, a PhD, a classics scholar who had read most of the books in the Berkeley library, and who had also been through several years of ROTC in high school. And so he did the obvious thing and went out and enlisted as a buck private in the army.

Hugh related:[6]

My first assignment [after basic training[7]]—it was so typically Army you must hear about it: It was the eve of Thanksgiving, and I was scrubbing toilets out with a big brush, with a big scrubbing brush. I was busy scrubbing these latrines out and so forth, and an officer came to me and said, “Come with me and bring the brush.” It was a huge pile of celery; they were preparing it for the officers’ mess the next day. He said, “Clean this celery off.” I said, “But this brush …I just used it for cleaning toilets!” “That doesn’t make any difference, if it looks shiny and clean, that’s the Army; that’s all we want to know.: So there I was cleaning that celery for the officers the next day for their Thanksgiving dinner with a toilet brush. That’s so typically army. I mean it’s marvelous, you know, and it just goes on.

Though Hugh approached his first encounter with army culture in a light-hearted way, most of his recollections stress the waste, the futility, the pain, and, above all, the evils of war. He said:[8]

[I remember General Bradley said, “War is waste!” And that’s what it is, you see. The utter wastefulness of the thing.] But the wrongness of what we were doing was so strong that everybody would cry. People would cry; they would weep. They would … tears would stream down … the wrongness. It was so utterly unspeakably sad! [It was so sad you could hardly stand it.] That people would do such things to each other.

Characteristically, Hugh, though loyal to his duty as a soldier, withdrew emotionally from the frenzy of selfish zeal and ambition that sometimes seemed to surround him on all sides:[9]

Men who had been waiting for twenty and thirty years for a war to get into were just itching for it. That was the happy war. It was the chance to get fast promotions. It was the big time; it was the chance for heroics. … There were men, officers, who just reveled in it because it was their life’s career. I’ll tell you if there was anything that puzzled me all the time I was there—I would say, “What on earth am I doing here? Why was I ever put in this situation?” I felt I was just an observer. “Why am I being shown this awful stuff? I don’t want to see it!”

As I listen to our Elders quorums [ringing] out [with] militant hymns every Sunday morning, slashing their swords above the foe, conquering at every step, scattering the hosts of darkness, reveling in the victory of the right — one question keeps recurring to my mind, “Where is the battle?” … The devil is using diversionary tactics to get us on the wrong battlefield. …

Satan’s masterpiece of counterfeiting is the doctrine that there are only two choices, and he will show us what they are. It is true that there are only two ways, but by pointing us the way he wants us to take and then showing us a fork in that road, he convinces us that we are making the vital choice, when actually we are choosing between branches in his road. Which one we take makes little difference to him, for both lead to destruction. This is the polarization we find in our world today. Thus we have the choice between Shiz and Coriantumr — which all Jaredites were obliged to make. We have the choice between the wicked Lamanites (and they were that) and the equally wicked (Mormon says “more wicked”) Nephites. Or between the fleshpots of Egypt and the stews of Babylon, or between the land pirates and the sea pirates of World War I, or between white supremacy and black supremacy, or between Vietnam and Cambodia, or between Bushwhackers and Jayhawkers, or between China and Russia, or between Catholic and Protestant, or between fundamentalist and atheist, or between right and left — all of which are true rivals, who hate each other. A very clever move of Satan! … It should be apparent that you take no sides [when you are presented with the devil’s dilemma].

Nibley recognized that the very same kind of battle is being waged in every sphere of action. In his well-known talk on “Leaders to Managers: The Fatal Shift,” he chronicled not only the sad leveling of leadership to the low bar of management,[13] but also, more broadly, the reduction of everything of priceless worth to the least common denominator—namely, the clink of cold cash:[14]

What are the things of the world? An easy and infallible test has been given us in the well-known maxim, “You can have anything in this world for money.”[15] If a thing is of this world you can have it for money; if you cannot have it for money, it does not belong to this world. That is what makes the whole thing manageable — money is pure number. By converting all values to numbers, everything can be fed into the computer and handled with ease and efficiency. “How much?” becomes the only question we need to ask. The manager “knows the price of everything and the value of nothing,” because for him the value is the price.

Look around you here [at the BYU graduation ceremony]. Do you see anything that cannot be had for money? Is there anything here you couldn’t have if you were rich enough? Well, for one thing you may think you detect intelligence, integrity, sobriety, zeal, character, and other such noble qualities. Don’t the caps and gowns prove that? But hold on! I have always been taught that those are the very things that managers are looking for—they bring top prices in the marketplace.

Does their value in this world mean, then, that they have no value in the other world? It means exactly that. Such things have no price and command no salary in Zion; you cannot bargain with them because they are as common as the once-pure air around us; they are not negotiable in the kingdom because there everybody possesses all of them in full measure, and it would make as much sense to demand pay for having bones or skin as it would to collect a bonus for honesty or sobriety. It is only in our world that they are valued for their scarcity. “Thy money perish with thee,” said Peter to a gowned quack [Simon Magus], who sought to include “the gift of God” in a business transaction.[16]

Nibley saw Moroni’s closing warning in the Book of Mormon as especially applicable in our day: “Deny not the gifts of God.”[17] To Nibley: “Everything you have is a gift— everything. You have earned nothing.”[18] But, whether one is speaking temporally or spiritually, people don’t seem to want gifts. We deny the gifts because we don’t want them— at least not as gifts:[19]

[We] want to say, “This is mine because I earned it.” … “But surely God expects us to work!” Of course he does, but we keep thinking of one kind of work, and he wants us to think of another.

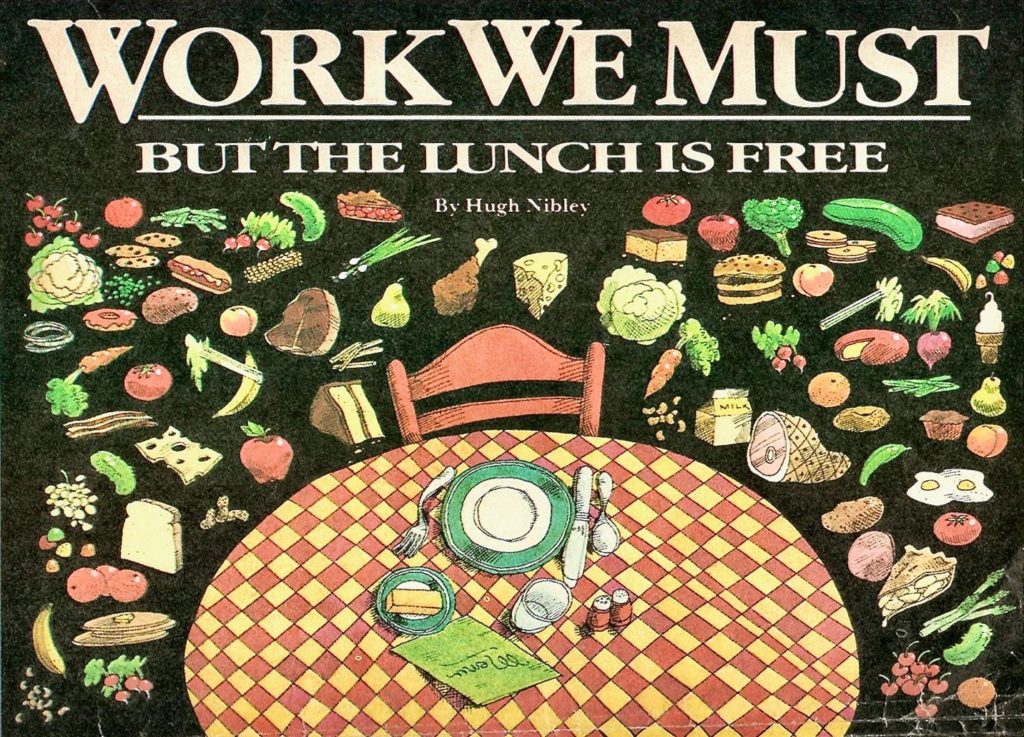

“Work we must,” explained Nibley, “but the lunch is free”:[20]

We have been permitted to come here [to earth] to go to school, to acquire certain knowledge and take a number of tests to prepare us for greater things hereafter. This whole life, in fact, is “a state of probation” (2 Nephi 2:21). While we are at school our generous patron has provided us with all the necessities of living that we will need to carry us through. Imagine, then, that at the end of the first school year your kind benefactor pays the school a visit. He meets you and asks how you are doing. “Oh,” you say, “I am doing very well, thanks to your bounty.” Are you studying a lot?” “Yes, I am making good progress.” “What subjects are you studying?” “Oh, I am studying courses in how to get more lunch.” “You study that? All the time?” “Yes. I thought of studying some other subjects. Indeed I would love to study them — some of them are so fascinating! — but after all it’s the bread-and-butter courses that count. This is the real world, you know. There is no free lunch.” But, my dear boy, I’m providing you with that right now.” Yes, for the time being, and I am grateful — but my purpose in life is to get more and better lunches; I want to go right to the top — the executive suite, the Marriott lunch.” “But that is not the work I wanted you to do here,” says the patron.

But if we leave off our constant preoccupation with acquiring and enjoying more and better lunches, what should we do instead? The basic answer should be obvious, but Nibley’s full response to this question is enlightening. This is something that readers would do well to explore on their own.[21]

In Hugh Nibley Observed, Don Norton related that when he finished editing the foreword to Nibley’s volume, Approaching Zion, “one of his most popular, albeit controversial, volumes” — and, it should be added, one that almost didn’t see the light of day — he phoned Hugh to ask him about the title for the volume:[24]

He muttered a few possibilities, then concluded., “Well, it ought to be titled Zion, but we’re not there as Saints yet. So let’s title it Approaching Zion.”

Here was a battle where Nibley was willing to take sides. Because he recognized that nothing in this life really belonged to him, the law of consecration became an easy yoke. He was all in for Zion. And there was no question in his mind about where on the playing field his efforts — and our own — would bear the best fruit:[25]

On the last night of a play the whole cast and stage crew stay in theater until the small or not-so-small hours of the morning striking the old set. If there is to be a new opening soon, as the economy of the theater requires, it is important that the new set should be in place and ready for the opening night; all the while the old set was finishing its usefulness and then being taken down, the new set was rising in splendor to be ready for the drama that would immediately follow. So it is with this world. It is not our business to tear down the old set — the agencies that do that are already hard at work and very efficient — the set is coming down all around us with spectacular effect. Our business is to see to it that the new set is well on the way for what is to come —and that means a different kind of politics, beyond the scope of the tragedy that is now playing its closing night. We are preparing for the establishment of Zion.

***

We hope you will enjoy the video interview of Jeff Bradshaw embedded here, which you can view in either long or short form. Jeff, one of the editors of Hugh Nibley Observed recounts how the idea for the book germinated, and discusses why Hugh Nibley’s example as a scholar and a disciple is more relevant than ever before.

In addition, a short video entitled ““What Five Things Did Hugh Nibley Teach Us About the Temple?” is embedded below, along with a more complete podcast and pdf transcript that are available for listening or download. The video introduces his lifelong scholarship on the temple — both as a house of learning and an example of selfless service. The law of consecration taught in the temple represented the pinnacle of Nibley’s personal strivings to be a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Insight – “What Five Things Did Hugh Nibley Teach Us About the Temple?” (PDF)

Insight – “What Five Things Did Hugh Nibley Teach Us About the Temple?” (audio)

Insight – “What Five Things Did Hugh Nibley Teach Us About the Temple?” (video)

A Conversation about Hugh Nibley with Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (complete)

A Conversation about Hugh Nibley with Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (short)

References

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Shirley S. Ricks, and Stephen T. Whitlock, eds. Hugh Nibley Observed. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2021.

Campora, Olga Kovárová. Saint Behind Enemy Lines. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1997.

Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh. 1985. “The faith of an observer: Conversations with Hugh Nibley.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 148–76. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008. http://www.bhporter.com/Hugh%20Nibley/The%20Faith%20of%20an%20Observer%20Conversations%20with%20hugh%20Nibley.pdf.

Nibley, Hugh W. “But what kind of work?” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 252-89. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Nibley, Hugh W., and Alex Nibley. Sergeant Nibley PhD: Memories of an Unlikely Screaming Eagle. Salt Lake City, UT: Shadow Mountain, 2006.

Nibley, Hugh W. “Beyond politics.” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon/Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 133-51. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1841&context=msr. (accessed September 20, 2020).

———. “Where is the battle? (from unpublished notes by Michael B. James).” n.d.

———. 1979. “Gifts.” In Approaching Zion, edited by D.E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 85-117. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1982. “Work we must, but the lunch is free.” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 202-51. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1983. “Leaders to managers: The fatal shift.” In Brother Brigham Challenges the Saints, edited by Don E. Norton and Shirley S. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 13, 491-508. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jxjZXAd300. (accessed January 16, 2020).

———. 1984. “We will still weep for Zion.” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 341-77. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Petersen, Boyd Jay. Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2002.

Notes

[1] H. W. Nibley, Weep.

[2] Courtesy of Marguerite Goldschmidt. Published in H. Nibley, Faith of an Observer, p. 164.

[3] Exodus 1:8.

[4] H. W. Nibley et al., Sergeant Nibley, p. 39.

[5] J. M. Bradshaw et al., Hugh Nibley Observed, p. 39.

[6] H. Nibley, Faith of an Observer, p. 163. Some small edits were made for consistency with the original film transcript.

[7] H. W. Nibley et al., Sergeant Nibley, p. 47.

[8] H. Nibley, Faith of an Observer, p. 165. Bracketed material is from B. J. Petersen, Nibley, p. 213.

[9] H. Nibley, Faith of an Observer, p. 165.

[10] Published in Hymns (1985), Hymns (1985).

[11] H. W. Nibley, Where is the battle? (from unpublished notes by Michael B. James); H. W. Nibley, Gifts, pp. 113–114. In her narrative describing her struggle in overcoming previous attitudes as she became a member of the Church in Communist Czechoslovakia, Olga Kovárová Campora wrote (O. K. Campora, Saint, p. 56):

I found that I was against anything that smelled of Communist ideology, but I also suddenly saw that my own life was focused only on fighting against the wall of the current ideology I lived in, and I had not found my own proactive direction. I realized I had forgotten about my private, personal well-being while fighting. I hadn’t made any time and effort except to fight against the dragon. Later I realized that one of Satan’s powerful tools is to surround a person with something so obviously negative that the person spends all of his or her energy only on nonsensical fighting, instead of turning their backs to it and trying find their own pace and direction. How much time did I waste only on pointing to the wrong side of the world, instead. of hiking towards a better future? Somehow this big beast of Communism had become the focus of my personal life, as it had for many of my fellowmen, and meanwhile I experienced a complete emptiness as I considered my human soul and its place in the world and in the universe. I didn’t know who I was, where I came from, or what the purpose of my life was.

[12] Published in BYU Today, November 1987, p. 8. Republished in J. M. Bradshaw et al., Hugh Nibley Observed , p. 754. The article was published in full in H. W. Nibley, Work.

[13] H. W. Nibley, Leaders, pp. 495–498.

[14] Ibid., pp. 503–504.

[15] The Testament of Job affirms the antiquity of the use of variations of this proverb by Satan and his allies: “Pay the price and take what you like” (R. P. Spittler, Testament of Job, 23:3, p. 848).

[16] See Acts 8:9-24.

[17] Moroni 10:8.

[18] H. W. Nibley, Gifts, p. 91.

[19] Ibid., pp. 90, 91, 101–102.

[20] H. W. Nibley, Work, p. 211.

[21] See, e.g., H. W. Nibley, But What Kind.

[22] https://dramaquarterly.com/tell-me-more/.

[23] Hymns (1985), Hymns (1985) , “Ye Elders of Israel,” no. 319.

[24] J. M. Bradshaw et al., Hugh Nibley Observed, p. 706.

[25] H. W. Nibley, Beyond Politics (2011), p. 151.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.