[Cross posted from Studio et Quoque Fide with slight alterations.]

Last year, Earl Wunderli published study claiming to show that the Book of Mormon was written by Joseph Smith strictly by internal evidence. It has been critically reviewed by Brant Gardner, Robert Rees, and Matt Roper with Paul Fields and Larry Bassist (forthcoming from BYU Studies Quarterly). For Wunderli, one of the curiosities that seems to indicate a 19th century authorship for the Book of Mormon is that, “when Jesus appears, he invites the multitude to thrust their hands into the sword wound in his side and feel the nail holes in his hands and feet. How Nephites would know the significance of the wounds is a question.” (Earl M. Wunderli, An Imperfect Book: What the Book of Mormon Tells Us about Itself [Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2013], 217.)

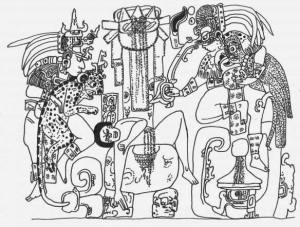

When I first read Wunderli’s comments, I must admit I was a little amused. Why? Last week’s paper from Interpreter is Mark Wright’s presentation “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” from the Temple on Mount Zion Conference in September of 2012. I love Wright’s work because he finds such subtle ways in which the Mesoamerican setting changes the way we understand the Book of Mormon and sheds light on perplexing issues. I remember being at the conference and listening to Wright. In it, he talks about Christ’s visit to the Nephites and Mesoamerican sacrifice. Wright explains:

The typical method of human sacrifice was to stretch the victim across a stone altar and have his hands and feet held down by four men. A priest would then make a large incision directly below the ribcage using a knife made out of razor-sharp flint or obsidian, and while the victim was yet alive the priest would thrust his hand into the cut and reach up under the ribcage and into the chest and rip out the victim’s still-beating heart. (emphasis mine)

Indeed, this is a very different method of sacrifice than crucifixion, and many among the Nephites likely would not have understood the method by which Christ was killed. But, Wright notices something interesting about how Christ invites them to see his wounds.

When Christ appeared to the Nephites, he may have been communicating with them according to their cultural language when he invited them to come and feel for themselves the wounds in his flesh. He bade them first to thrust their hands into his side, and secondarily to feel the prints in his hands and feet (3 Nephi 11:14). This contrasts with his appearance to his apostles in Jerusalem after his resurrection. Among them, he invited them to touch solely his hands and feet (Luke 24:39–40). Why the difference? To a people steeped in Mesoamerican culture, the sign that a person had been ritually sacrificed would have been an incision on their side — suggesting they had had their hearts removed — whereas for the people of Jerusalem in the first century, the wounds that would indicate someone had been sacrificed would have been in the hands and the feet — the marks of crucifixion. (emphasis mine)

Obviously, Christ was not sacrificed in a Mesoamerican way, with his heart ripped-out. But the crucial point for all to understand is not how he was sacrificed, merely that he actually was sacrificed. A mark on the side, below the ribcage, would have communicated that message to Nephites in Mesoamerica quite effectively.

In contrasting Wright’s insightful approach with that of Wunderli’s, there is an important lesson to be learned: perspective and context can change everything. There really is no such thing as a wholly “internal” reading of the text. We all bring perspectives, assumptions, and understandings to the text that are external to it, and drive our interpretations of it. Wunderli does not read the text through a Mesoamerican lens (and would not be capable of so doing, in any case), and so he finds Christ’s showing of his wounds to be a curious feature, bringing in the assumption that the wounds would make no sense to anyone outside of the Roman empire. Meanwhile, Wright shows a careful reading comparing Christ’s showing of wounds in both the Old World and the New, notices the subtle differences, and seeks to understand how a setting within the New World serves to explain those differences. I’ll leave it to readers to decide for themselves which reading is more productive.

I guess you can read into the text whatever you want and Wunderli shows a priori assumptions. How do we know that there was not a more extended dialogue between the masses and the Saviour? Who was in ear shot when the dialogue took place. Maybe the intimal dialogue was passed along, like Chinese whispers and was watered down to what we have today. Maybe a few in the crowd knew the significance of the wounds and told others, therefore avoiding the need of the Saviour to tell each attendee. There could be many explanations, but they wouldn’t suit Wunderli’s argument. He’s a lawyer, not a historian, nor an archaeologist, after all.