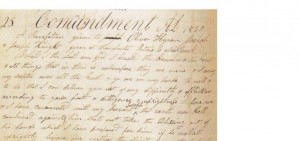

A Revelation given to Joseph Oliver [Cowdery] Hyram [Hiram Page] Josiah [Stowell]

& Joseph Knight given at Manchester Ontario C[ounty] New York

Behold I the Lord am God I Created the Heavens & the Earth

& all things that in them is wherefore they are mine & I sway

my scepter over all the Earth & ye are in my hands to will &

to do that I can deliver you o{◊\ut} of evry difficulty & affliction

according to your faith & dilligence & uprightness Before me

Joseph

& I have cov{◊\enanted} with my Servent^ that earth nor Hell

combined againsts him shall not take the Blessing out of

his hands which I have prepared for him if he walketh

uprightly before me neither the spiritual nor the temporal

Blessing & Behold I also covenanted with those who have assisted

him in my work that I will do unto them even the same

Because they have done that which is pleasing in my sight

(yea even all save ◊◊tin only it be one o{l\nly}) Wherefore be

dilligent in Securing the Copy right of my Servent work

upon all the face of the Earth of which is known by you

unto unto my Servent Joseph & unto him whom he willeth

accordinng as I shall command him that the faithful & the

righteous may retain the temperal Blessing as well as the

Spirit[u]al & also that my work be not destroyed by the workers

of iniquity to the{r\ir} own distruction & damnation when they

are fully ripe & now Behold I say unto you that I have coven=

=anted & it Pleaseth me that Oliver Cowderey Joseph Knight Hyram

Pagee & Josiah Stowel shall do my work in this thing yea

Copy

even in securing the ^ right & they shall do it with an eye single

to my Glory that it may be the means of bringing souls

unto me Salvation through mine only Be{t\gotten} Behold I am

God I have spoken it & it is expedient in me Wherefor I say

unto you that ye shall go to Kingston seeking me continually

through mine only Be{t\gotten} & if ye do this ye shall have my

spirit to go with you & ye shall have an addition of all things

amen

which is expedient in me^. & I grant unto my servent a privelige

a copyright

that he may sell ^ through you speaking after the manner of

men for the four Provinces if the People harden not their hearts

against the enticeings of my spirit & my word for Behold it

lieth in themselves to their condemnation &{◊\or} th{er\eir} salvation

Behold my way is before you & the means I will prepare

& the Blessing I hold in mine own hand & if ye are faithful

I will pour out upon you even as much as ye are able to

Bear & thus it shall be Behold I am the father & it is through

mine o{◊\nly} begotten which is Jesus Christ your Redeemer amen

Today the new volume from the Joseph Smith papers project came out. I went and looked at this revelation at the BYU bookstore and decided to wait until they have a 25% off sale next Monday.

The FAIR wiki’s entry will have to be updated. http://en.fairlatterdaysaints.org/Did_Joseph_Smith_attempt_to_sell_the_Book_of_Mormon_copyright%3F

That is just one many things I hope commenters will discuss.

“…he [Whitmer] did not correctly identify all of the participants (he identified Hiram Page and Oliver Cowdery, while Page noted Joseph Knight and Josiah Stowell).”

http://en.fairlatterdaysaints.org/Did_Joseph_Smith_attempt_to_sell_the_Book_of_Mormon_copyright%3F

“…it Pleaseth me that Oliver Cowderey Joseph Knight Hyram

Pagee & Josiah Stowel shall do my work in this thing…”

Some background on the copyright revelation was posted here.

http://www.examiner.com/examiner/x-19393-Salt-Lake-City-Mormon-History-Examiner~y2009m9d22-Joseph-Smiths-Copyright-Revelation

Yes, the revelation resolves one mystery of who the participants are. I am inclined to believe David Whitmer’s report of the subsequent revelation than the wiki is although it didn’t get recorded. It also seems like there was a thought of preparing the revelation for publication based on all the editing and corrections. So David Whitmer is the only one who thought it was a false revelation. Hyrum Page and the text of the revelation show it was a conditional revelation.

Page certainly understood the revelation to be conditional, but he also notes that there was no way to secure the copyright at Kingston, as they had been sent to do. The real issue with the revelation was not that the sale did not occur but that it (reportedly) wasn’t even possible to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it. Further research needs to be done to assess whether what Page, et al. were told was accurate. Could copyrights be secured in Kingston? Or did one have to do this in Toronto? What was the law of the time?

Kingston is closer to Ottawa, which became the capitol. Canada was still a dominion of Britain at the time. Kingston was a major city in Joseph Smith’s time.

Are there transcriptions of other revelations not published in D&C?

In his discussion of the 1830 revelation regarding the proposed sale of the copyright to the Book of Mormon in Kingston, Don Bradley states that there is a question “of whether the copyright could have been secured in Kingston.” He states that question “remains open.”

His contention is this:

“Those sent to Kingston were given the understanding that they could not copyright the book there.” Of course, the revelation speaks nothing about the securing of a copyright (or hte copyrighting of the book) in Kingston (or anywhere in Upper Canada); rather, it speaks only of the sale of the copyright. The copyright is intangible personal property, owned by the Prophet and the Church at the time. It could be sold much like other intangible personal property.

Mr. Bradley states that the editor of the Book of Commandments and Revelations “removed elements [of the revelation] promising that a copyright could be secured and sold in Kingston.” Yet, there are no elements regarding securing the copyright in Kingston, only elements of sale of the copyright there. Sale of intangible personal property could of course have occured in Upper Canada.

Mr. Bradley states that “legal research is needed to determine whether it a copyright [sic] could have been secured in Kingston.” No such research is needed, for the securing (or obtaining) of a copyright in Kingston was not at all contemplated by the revelation.

Mr. Bradley asserts that if the copyright could not have been secured (obtained) in Kingston, “then the revelation would appear to have promised the impossible . . .”

To respond to Mr. Bradley’s request for legal research, allow me to supply the following discussion.

RELEVANCE OF KINGSTON AS A PLACE

The revelation was received in 1830 in Manchester, near Palmyra, and Kingston was not only the Canadian population center nearest to Manchester (187 miles, 300 kilometers distant; see http://snipurl.com/sjt3t), until the 1840s it was the largest population center in Upper Canada (http://snipurl.com/sjt35). Indeed, Kingston (previously known as Kings Town) was of such early importance that it was chosen as the first capital of the united Canadas, serving in that role from 1841 to 1844; in 1830, however, Canada was not united and there was no one capital. But Kingston was the major population center of Upper Canada at the time. And it was the closest to Manchester.

LEGAL RESEARCH ON COPYRIGHT LAW IN PRE-1841 ONTARIO

British statutory copyright law goes back to 1710, but it was not until 1832, with the enactment of the Provincial Statutes of Lower-Canada (http://snipurl.com/sjtaj), that provision was there first made for authors and composers (and their executors, administrators, and legal assigns) to enjoy the sole right to print, reprint, publish, and sell their works (for a term of 28 years). And it was not until 1841 that this statute was extended to Upper Canada.

So, again, what we are dealing with here is not the ability to obtain a copyright in Kingston or to sell the Book of Mormon in Canada pursuant to any statute in existence and applicable in Upper Canada at the time that would give the Prophet the sole right under a Canadian statute to print, reprint, publish, or sell the Book of Mormon (for no such statute then existed). Rather, what we are dealing with in copyright law (if we should be dealing with copyright law at all) is the ability to protect the Prophet’s and the Church’s interest in the exclusive rights to publishing the Book of Mormon within the area of Upper Canada. (I say, “if at all” because actually we should be dealing only with, as the revelation itself states, the ability to sell the copyright in Kingston, not the obtaining of a copyright there.)

So what, if any, law applied to the sale (or obtaining, if you will) of copyrighted materials in pre-1841 Upper Canada? “The copyright protection provided by the Statute of Anne and the U. S. Copyright Act did not protect authors from foreign publishers who printed and sold the author’s work in that foreign country. The problem first came up when Irish publishers, to whom the Statute of Anne did not apply, began to print, sell and export cheap reprints of works by English and Scottish authors.

“In the 1800s the author Charles Dickens drew attention to the problem of cheap foreign editions when he objected to his works being published without his permission both in the United States and in British colonies. Later it was an American author, Mark Twain, who objected to his works being published in Canada without his permission. Countries began to deal with problems of this sort by entering into bilateral treaties. These treaties required each country to give the citizens of the other country the same copyright protection their own citizens enjoyed.” (Julien Hofman, “Introducing Copyright,” (Commonwealth of Learning: Vancouver, 2009) p. 8.)

But it was not until the second half of the 1830s when the need for agreements on international copyright protection came to be recognized in the U.K. It was only then, after 1830, when an international copyright bill was first presented to Parliament by Charles Poulett Thomson (1799-1841), enacted at the end of July 1838. (See Akiko Sonoda, “Historical Overview of Formation of International Copyright Agreements in the Process of Development of Internatioal Copyright Law from the 1830s to 1960s” (IIP Bulletin, 2007), p. 2.)

Prior to then, copyright protection of works by American authors would have been provided by provincial laws. But no such laws existed at the time that would extend protection to works by American authors (just the same as in America, the U. S. Copyright Act did not extend protection to foreign authors). It would not be until 1885, with the enactment of the Berne Convention, that a uniform international system of copyright would become law. And it would not be until the Anglo-American copyright of 1891 that the end of piracy would come; prior to that, Canadian publishers were not obliged to pay royalties to American authors; instead, they merely pirated the works and sold them (both in Canada and as cheap versions in America). Hence, the way the Prophet sought to protect his and the Church’s interest in the rights to publishing the Book of Mormon was essentially the only way: sell the copyright to a publisher in Canada. Obviously this meant the rights to priting the book in Upper Canada, not the rights to printing the book everywhere.

(The above is a mere preliminary discourse into the topic; detailed research into the local laws that may have existed in Ontario in the 1820s and early 1830s was not attempted.)

My guess would be Stephen Ehat is an attorney. To take a basic historical event and turn it into gobbledygook is something only an attorney could accomplish.

As for your distances and population numbers I found a few differences. Toronto is actually closer to Manchester than Kingston using your link to the google map. I don’t know if this was true in 1830, but it is in 2009. Even if Toronto was a few miles further on 1830 roads, so what!

As for population numbers. I can find none for 1830 Kingston. All I can find is statements that it was the largest population center in the 1840s so that is why it was chosen to be the capital. I can find hard numbers for Toronto. In 1834 Toronto had 9,000 population, 1840 it had 16,000 and in 1851 Toronto had 30,775 and Kingston had 11,585.

But none of this addresses Don Bradley’s original comment.

From my research only British subjects could hold copyright in Canada. No matter how faithful Joseph Smith, Hyrum Page or Oliver Cowdery were, they neither were British subjects nor would the miraculously become one on this trip. Why would a British subject be interested in paying for an American work or copyright when he or she was free to publish the work at will with out any worry of legal recourse?

I agree with you, Mr. Geisner, but I think your insightful post supports the point I am making. While the revelation expressly refers three times to the copyright — the first two references being about “securing” the copyright in all the world (the first of those references using the phrase “upon all the face of the Earth”) — the third reference mentions nothing about securing the copyright; rather it speaks in terms of selling the copyright.

Responding to Mr. Bradley’s suggestion that “legal research” is needed (it is he, not I, who suggested it; and probably appropriately so, in one sense, for after all, copyright is legal in nature, not “historical event”), I agree with you that it would make no sense to seek to sell the copyright for the four provinces of Canada if the copyright had no value. But did it?

While America notoriously provided no protection within its borders for works sought to be sold there written by foreign authors, the same might not be the situation in Canada for works sought to be sold there written by foreign (American) authors. Mr. Bradley invites legal inquiry into “whether it a copyright [sic] could have been secured in Kingston.” Of course, the revelation does not speak of securing it in Canada, only of selling it there. But, to be fair, his request for “legal research” does invite an approach to his basic question: Was it even possible for the Prophet to obtain protection of the Book of Mormon in Canada?

Putting aside the point about the difference between obtaining the copyright in Canada and selling it there, when one looks for the reason why the Prophet would look to sell his American copyright in Canada, one must wonder if it indeed had any value there; in other words, the question ought to be whether the Prophet’s and the Church’s American copyright could be recognized (i.e., have value) in Canada. You and Mr. Bradley would say “no”; I would say “yes.”

Though neither I nor you have actually substantiated the point with citation to a statute or law, it is possibly correct that pre-1841 copyright law internal to Ontario or internal to the United Kingdom and applicable in Ontario protected only works by British subjects. But I do not know that actually was the case. You use the phrase “only British subjects could hold copyright in Canada”; that gets almost the same point across (there’s a slight difference, I suppose, between holding a copyright in Canada and having Canada recognize an American copyright). But the thrust of your point is well taken and raises the core point: could only a British subject enjoy copyright protection within Canada (whether by means of “holding a copyright in Canada” or otherwise).

At the time, “American authors visited Canada in order to satisfy the more lenient British regulations which permitted copyright protection for books whose authors were within the borders of Britain or its colonies at the time of publication.” See Chapter 9, “American Copyright Piracy,” in B. Zorina Khan, “The Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790-1920” (Cambridge University Press, 2004), at pg. 9.14.) This protection possibly could have been obtained during Oliver Cowdery’s visit there in connection with his attempt, with others, to sell the copyright there.

While the “legal research” invited by Mr. Bradley into the question of “whether it a copyright [sic] could have been secured in Kingston” is, in my mind, beside the point and not the appropriate inquiry invited by the text of the revelation (which, at that point, speaks of the sale of the American copyright, not the obtaining of a Canadian copyright), the real issue — “Did the American copyright have value in Canada?” — can indeed probably be discerned by recourse to legal research (which, I repeat, I have not done). It may be that no international treaties then existed providing for reciprocity and it may be that no internal laws of Ontario or of the U.K. applicable to Ontario provided direct protection for foreign authors; but perhaps some other regulations provided some sort of protection (e.g., value in the American copyright), making the trip to Kingston entirely worth pursuing.

Your main inquiry is a valid one: “Why would a British subject be interested in paying for an American work or copyright when he or she was free to publish the work at will without any worry of legal recourse?” Probably because an American, at the time, could indeed go to Canada and publish his work and indeed be protected by Canada’s law (without being a citizen) and thus, by selling his American copyright to one publisher in Canada, he would allow that one Canadian publisher thereby to be entitled to exclude other Canadian publishers from profiting from publishing the work.

(The above is a mere preliminary discourse into the topic; detailed research into the local laws that may have existed in Ontario in the 1820s and early 1830s was not attempted.)

Here are the results of some preliminary literary and legal research regarding the question of “obtaining” a copyright in Upper Canada for the Book of Mormon. On this blog (above), Mr. Bradley states that Hiram Page “notes that there was no way to secure the copyright at Kingston, as they had been sent to do” and Mr. Bradley adds that “the real issue with the revelation was not that the sale did not occur but that it (reportedly) wasn’t even possible to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it.” Mr. Bradley states (above) that “further reserch needs to be done.” Elsewhere (http://www.mrm.org/attempt-to-sell-copyright), Mr. Bradley similarly states that “Legal research is needed to determine whether it a copyright [sic] could have been secured in Kingston.” Above he asks, (1) “Could copyrights be secured in Kingston?”; (2) “Did one have to do this in Toronto?”; and (3) “What was the law of the time?”

As I’ve noted in some preliminary musings above, these questions seem to be, technically, the wrong questions because the revelation speaks generally of securing the copyright “upon all the face of the Earth” but as to Kingston specifically the revelation speaks only of “sell[ing]” a copyright. Nevertheless, putting aside that difference, which may or may not be of some relevance, some preliminary literary and legal research clearly indicates that a copyright could indeed be both obtained (secured) and sold in Kingston.

LITERARY ANALYSIS

Prior to 1830 (and since 1814), it appears that at least five publishers—Stephen Miles, Hugh C. Thompson, James McFarlane [also Macfarlane], the Gazette Office, and the Herald Office—had both printed and published at least thirty books and pamphlets in Kingston, Upper Canada. See “Books and Pamphlets Published in Canada, Up To the Year Eighteen Hundred and Thirty-Seven, Copies of Which Are in the Public Refernece Library, Toronto, Canada” (Toronto: Public Library, 1916), pp. 15-39; see also William Kingsford, “The Early Bibliography of the Province of Ontario, Dominion of Canada, With Other Information” (Toronto: Roswell & Hutchison, 1892, and Montreal: Eben Picken, 1892), pp. 27-29, 31-33, 35.

Given here in abbreviated form, the titles of the thirty publications identified in the above two bibliographical references are: (1) [1814]. “A Form of Prayer and Thanksgiving to Almighty God to be used on Friday, the Third Day of June, 1814″ (pamphlet, 14 pages); (2) [1815] “A short account of the life and dying speech of Joseph Bevir, who was executed at Kingston (Upper Canada) on Monday the 4th day of September, 1815″ (pamphlet, 32 pages); (3) [1818] “Address to the Jury at Kingston Assizes, in the Case of the King v. Robert Gourlay, for libel, with a report of the trial”; (4) [1818] “Essay on Modern Reformers addressed to the people of Upper Canada, to which is added a letter to Mr. Robert Gourlay” (pamphlet, 19 pages); (5) [1821] “The Prompter A Series of Essays on Civil and Social Duties” (phamplet, 56 pages); (6) [1822] “An Address to the liege men of every British Colony and province in the world by a friend to his species” (pamphlet, 13 pages); (7) [1823] “Constitution of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons” (book, about 140 pages); (8) [1823] “Examination of a Pamphlet entitled ‘A Statement of facts relating to the failure of the Bank of Upper Canada at Kingston” (pamphlet, 23 pages); (9) [1824] “A warning to the Canadian Land Company in a letter addressed to that body by an English resident in Canada” (pamphlet, 32 pages); (10) [1824] “Letter to C. A. Hagerman, by Thomas Dalton”; (11) [1824] “St. Ursula’s Convent ; or, the Nun of Canada containing scenes from real life” (fiction, two volumes, 237 pages); (12) [1825] “First Annual Report of the Canada Conference Missionary Society, Auxiliary to the Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church”; (13) [1826] “A letter to the Right Honourable the Earl of Liverpool, K.G., relative to the rights of the Church of Scotland in North America”; (14) [1826] “An Apology for the Church of England in the Canadas, in answer to a letter to the Earl of Liverpool, relative to the rights of the Church of Scotland”; (15) [1826] “Reports of the Commissioners of Internal Navigation appointed by His Excellency, Sir Peregrine Maitland, K.C.B.”; (16) [1826] “The exclusive right of the Church to the Clergy Reserves, defended in a letter to the Right Honorable the Earl of Liverpool”; (17) [1827] “A sermon preached at Kingston, Upper Canada, on Sunday, the 25th Day of November, 1827″; (18) [1827] “A series of reflections on the management of Civic Rule in the town of Kingston”; (19) [1827] “Statement of the affairs of the late Pretended Bank of Upper Canada at Kingston” (pamphlet, 48 pages); (20) [1828] “Letter from the Reverend Egerton Byerson to the Hon. and Reverend doctor Strachan”; (21) [1828] “Manual of Parliamentary Practice with an Appendix Contaning the rules of the Legislative Council, and House of Assembly of Upper Canada” (pamphlet, 92 pages); (22) [1828] “Religious Discourses, by the author of Waverley”; (23) [1828] “Claims of the Churchmen and Dissenters of Upper Canada brought to the test”; (24) [1828] “The Charter of the University of King’s College at York, in Upper Canada” (pamphlet, about 23 pages); (25) [1828] “The Address to Protestant Dissenters, suited to the present times” (phamplet, 52 pages); (26) [1828] “Religious discourses. By the Author of Waverley (Sir Walter Scott)”; (27) [1828] “The Charter of the University of the King’s College at York in Upper Canada”; (28) [1828] “Second Report of the Midland District Committee of the Society for promoting Christian Knowledge”; (29) [1829] “The Lower Canada Watchman, Pro Patria” (book, 491 pages); and (30) [1829] “A letter from the Honourable and Venerable Dr. Strachan, Archdeacon of York, U.C., to Dr. Lee, D.D., Convener of a Committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.”

That there purportedly “was no way to secure the copyright at Kingston,” in support of which notion Mr. Bradley cites Hiram Page, seems difficult to credit, what with at least five publishers having published at least 30 publications in Kingston the years prior to 1830. Indeed, the publication by Hugh C. Thomson of Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart’s 1824 piece of fiction, “St. Ursula’s Convent” (fiction, two volumes, 237 pages) and by James Macfarlane of David Chisholme’s “The Lower Canada Watchman” (political book 491 pages) seems adequate evidence of the availability of at least two publishers or printers in Kingston who had the wherewithal to register copyrights, not to mention publish a book the length of the Book of Mormon; clearly those publishers (and most likely all the others) had registered copyrights previous to 1830.

So to answer Mr. Bradley’s first question (“Could copyrights be secured in Kingston?”), it seems clearly that the answer is “yes,” at least to the extent that question is interpreted to ask whether there were the necessary helps in that town to facilitate accomplishment of the task. (This answer happily acquiesces to the questioner’s use of the colloquial, and not incorrect, word “secured”; that is a word commonly used (even in the text of the revelation under discussion) even though, perhaps to make too fine a point, a copyright exists upon publication and is merely registered, not “secured.”) And to answer Mr. Bradley’s related question (“Did one have to do this in Toronto?”), it seems that the answer to that question, too, is “no.” While York (as Toronto was known at the time—from 1793 to 1834) also was replete with publishers, Kingston was not bereft of them.

LEGAL ANALYSIS

Mr. Bradley’s assertion that “it wasn’t even possible to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it” and his related (third) question (“What was the law of the time?”) invite inquiry into whether it indeed was legally permissible for these agents of the Prophet Joseph Smith to succeed in Kingston either in selling “a copyright” there (as the revelation expressly states) or in “securing” a copyright there (as Mr. Bradley reads the revelation to mean). The answer to that question (however understood) seems clearly to be “yes.”

First, of course, copyrights had value and could be sold. In 1774, the House of Lords decided the case of Donaldson v. Beckett. The issue in that case was whether copyright existed at Common law undisturbed by the Statute of Anne. (8 Anne, c. 19.) Prior to the Statute of Anne, neither statute expressly created nor judicial decision expressly recognized copyright. Nonetheless, authors and printers recognized literary property rights and when statutes and court decisions began to address the question, they indirectly recognized the existence of literary property, both before and after publication, as part of the common law.

Section 1 of the Statute of Anne provided that “From the 10th of April, 1710, the author of any book already printed, who shall not have transferred the right, shall have the sole right and liberty of printing such book for the term of twenty-one years to commence from the said 10th day of April and no longer . . . .” Hence, though a book may already be published, an author retains a valuable property right therein for a period of time. In 1769 the Court of Common Law decided the celebrated case of Millar v. Taylor (4 Burr. 2319). The poet Thomson had published his poem, “The Seasons,” in the years 1726-1730; statutory copyright therefore expired in 1758. Thomson sold the copyright to Millar and in 1763 Taylor pirated the work. In 1766 Millar brought an action against Taylor, which action was heard before Lord Mansfield, O.J., Willes, Yates, and Aston, JJ., and decided in 1769. The judges held by three against one that the copy of a book or literary composition belongs to the author by the common law, and that this common law right of authors to the copies of their own works is not taken away by the Statute of Anne. Thus the first discussion of the matter in Courts of Law resulted in the affirmation of a copyright at common law undisturbed by the statute.

Thereafter, in 1774, a court in Scotland denied the existence of literary property rights at common law and an appeal was taken to the House of Lords. The case was Donaldson v. Beckett (4 Burr. 2408). The facts were the same as in Millar v. Taylor, except that Millar’s executors had sold the “copy” to Beckett, who prosecuted Donaldson for piracy. The Scottish court’s Lord Chancellor granted a perpetual injunction against Donaldson and Donaldson appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords called in the judges to give their respective opinions on five questions. (1) Over one dissenting judge, ten judges (and Lord Mansfield) were of opinion that at common law an author of any book or literary composition, before publication, had the sole right of first printing and publishing the same for sale, and might bring an action against any person who printed, published, and sold the same without his consent. (2) Over three dissenters, eight judges (and Lord Mansfield) opined that if the author had such a right originally, the common law did not take it away upon his printing or publishing such book and a person afterwards was not entitled to reprint and sell for his own benefit such books against the will of the author, the large majority thus holding that publication did not at common law divest copyright. (3) However, over five dissenters (including Lord Mansfield), six judges said that if such an action would have lain at common law, it is taken away by the Statute of Anne; and an author is precluded from every remedy, except on the foundation of the statute or on the terms and conditions prescribed therein. (4) Over four dissenters, seven judges (and Lord Mansfield) ruled that the author of a book, and his assigns, had the sole right of printing and publishing the same in perpetuity by the common law. (5) The fifth question practically repeated the third: “Whether this common law right is in any way impeached, restrained, or taken away by the Statnte of Anne?” On this, after discussion of the wording and circumstances of the statute, six judges answered “Yes”; five (and Lord Mansfield) “No.”

On these answers of the judges, Lord Camden moved the House of Lords to give judgment for the appellant, Donaldson, and against the existence of the common law right. The House of Lords agreed and denied the existence of a perpetual common law copyright, holding that copyright was purely a creation of statute and could be limited in its duration.

Booksellers, who stood to gain the most by the existence of a common law right in perpetuity, immediately went to Parliament for relief. They lost. The next ensuing copyright legislation was not enacted until 1837.

So this was the state of the law, in general terms, in 1830, the time of the revelation. And insofar as concerns the question posed by Mr. Bradley here in this blog, the two salient, important features of copyright law in existence in the realm in 1830 were these: (1) copyright and its duration in England (and in its Dominions, including Upper Canada) was governed by the Statute of Anne, and (2) though a book may already have been published, an author retains a valuable property right therein (in its copyright) for a period of time.

On this latter point it is noteworthy that when on February 28, 1774, the booksellers presented their petition, they complained that in reliance on what they had always understood to be their common law right—confirmed by the case of Millar v. Taylor—they had invested several thousand pounds in the purchase of copyrights. These pepetual-term copyrights were now left unprotected by the Statute of Anne (for they were older than the statutory period allowed for by that act). But in support of their otherwise unsuccessful petition, the booksellers produced as their chief witness a bookseller who testified to the value of copyrights, asserting that in the previous twenty years nearly £66,000 had been paid for copyrights by publishers. Clearly, copyrights had value and could be sold or assigned by sale, gift, bequest, by operation of law, or otherwise. That much was undeniable, regardless whether perpetual copyright protection existed under the common law or whether a limited term copyright protection existed solely under the Statute of Anne.

Hence, the remaining question inspired by Messrs. Bradley and Geisner is whether a copyright to a book could be sold in Upper Canada in the circumstance where the seller of a copyright of the book was a foreigner and the book had already been published in the United States. On this question, the opinion of the Court of King’s Bench in the case of Clementi v. Walker (2 B. & C. 861) is relevant. In the Clementi case, a French author had purported to assign orally [note that: “orally”] to an English subject the exclusive right of printing and publishing a musical composition in England. The court held that the purported assignees did not acquire the exclusive right to publish in England because the purported assignment was oral only and not in writing. The facts were these: Clementi and others were the proprietors of the copyright for a book of musical composition called “Vive Henri Quatrea,” a celebrated French national air. Mr. F. Kalkbrenner composed the music in France in the summer of 1814. Before he came to England, which he did in June of that year, he agreed orally with Mr. Pleyel, a publisher of music in Paris, that Mr. Pleyel should have the right of publishing the music in France only, reserving to himself the right to publication in England. Before it was published in France, Mr. Kalkbrenner left France and went to England. Shortly after Mr. Kalkbrenner arrived in England, on July 12, 1814, he sold the work by an oral agreement. The plaintiffs, purchasers of the work in England, published it there between September 3 and 10, 1814. Meanwhile, the work was not published in France until 1815.

On the 24th of January 1822, Kalkbrenner, being in England, executed an assignment in writing [note: “in writing”] of his copyright in the musical composition in question to the plaintiff agreeably to the terms of sale made by him to them in 1814. The defendant sold a copy of the work in question to Mr. Lindsey on the 20th of February, l822, at his shop in London, for two shillings. Each copy was on English paper and from an English engraving. The Son of the defendant, in 1818, parchased a copy of the composition published by Pleyel at a shop in France, with a number of others by the same author, which the defendant caused to be engraved and published in England, in December, 1818. The defendant’s edition was a facsimile of the copy so purchased by his son, and there was no difference between that edition and the edition published and sold by the plaintiffs in England. There is a register kept at Paris, and by the law of France all musical publications must be registered, and a copy of the said composition was duly registered and deposited there on the 17th of June, 1814. The defendant’s son never heard or saw the composition until he saw it at the shop in Paris in 1818.

The plaintiffs insisted that they, as the proprietors of the copyright, were entitled to recover. They argued that the statute (8 Anne, c. 19) gave the sole right of printing any book to the author or his assignee for fourteen years, “to commence from the day of his first publishing the same.” Argued the plaintiffs, the right vested in the author in 1814 (when the book was first published in England and continued in the author until he executed a valid assignment of it to the plaintiff in 1822; and there being a sale of a copy of the work after that period by the defendant, a good right of action thereby accrued to the plaintiff.

The defendant contended that there having been, by the assent of the author, a previous publication of the work in a foreign country (France), he could not afterwards claim the exclusive right of publishing it in England. By the statute of Anne, argued the defendant, the exclusive right is given to the author for a term to commence from the time of his first publishing the same; all the statutes upon this subject contemplate a work published for the first time in England. “The author in this case, by once publishing his work in France, dedicated it to the public, and cannot afterwards claim an exclusive copyright in this country.” Indeed, “[t]he plaintiffs acquired no right until 1822. The defendant had before that time published the work here . . . . Having once published, it was not competent to the author after such lapse of time to claim the exlusive right of publishing in this country.”

The court agreed with the defendants. But note the court’s reasoning: “The first question in this case is, whether the publishing of the work, in September 1814, gave to the plaintiffs [the purported assignees] the privileges conferred upon authors by the legislature, and we are of opinion that it did not, because there was not any assignment or consent in writing given by the author previously to that publication. The case of Power v. Walker is an authority to shew that a parol [oral] assignment is not sufficient to give to the assignee the privileges conferred by the legislature upon the author.”

Clearly, therefore, the reason the plaintiffs could not sue was only because they did not have a valid assignment granting unto them “the privileges conferred upon authors by the legislature.” Note otherwise that the court does, indeed, recognize that in this inter-country fact situation, the legislature (by the Statute of Anne) was—but for the faulty assignmentvviewed as having conferred copyright privileges on the author. And, to be clear, in this case the author had composed the music in France and then had gone to England to cause it to be published in England (albeit by others to whom he had attempted to make what ultimately was a mistakenly invalid oral assignment).

A second question addressed by the court in the Clementi case was whether the protection and exclusive privilege “extends to cases where he [the author] is the first who publishes abroad, and afterwards is publisher here [in England], but not until after a reasonable time for his publishing here has elapsed.” Stated differently, the court framed the issue thus: “[W]hether an author who first publishes abroad, and instead of using due diligence to publish here, forbears to publish until some other person, fairly without blame, publishes here, can insist upon his privilege, and, at a distance of time, stop a publication, which, in the interim, has taken place here, and treat the continuance of that publication as a piracy, and we are of opinion that he cannot.”

So in Clementi v. Walker, the plaintiffs were those who purportedly received an assignment in 1814 and sought in 1822 to enforce a copyright under which the author had delayed publication. That clearly was not the situation with the Prophet Joseph Smith. First, there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever that any assignment (in his case, assignment by sale) of a copyright was to be oral instead of in writing. To argue otherwise is to argue from silence; such a fact was, at the time of the recordation of the revelation, a yet-future conditional event. And second, the Book of Mormon had first been announced for publication on March 26, 1830; the revelation under consideration was received in early 1830. Absent a faulty assignment (sale) in the Prophet’s situation and absent delay in seeking publication in Upper Canada, what the court in Clementi otherwise would have ruled would be the same rule applicable here: an author who published abroad (be it France or America) can publish in England (or one of its Dominions) and obtain copyright protection under the Statute of Anne.

Mr. Geisner recently states (see his October 16, 2009 posting) that from his “research only British subjects could hold copyright in Canada.” Not so. In Tonson v. Collins, 1 Wm. Blackstone 301, 96 Eng. Rep. 169 (1761), the question of copyright was carefully considered, and even Mr. Thurlow, in arguiug against it, admitted that “it is of no consequence whether the author is a natural-born subject, because this right of property, if any, is personal, and may be acquired by aliens.” And on this point, it should be remembered that it was property (“a copyright”) that the emissaries of the Prophet were sent to sell. And further, discussing Clementi v. Walker (a case that predates the 1842 Copyright Act), the House of Lords had the following to say about Clementi in the case of Jefferys v. Boosey (4 H.L.C. 815) (a case that postdates the 1842 Copyright Act), where the Jeffreys case justices stated that the decision arrived at in Clementi “could not have occurred if the fact of the author being a foreigner had been an answer to the claim.” In other words, if it were as simple as saying in the Clementi case that the French author should lose the case merely because he was foreign, then the court would have been hard pressed to come up with the more elaborate ruling that it did come up with to the effect that the faulty attempted oral assignment and the delay in publication were the reasons the plaintiffs failed.

Elaborating on this very point, Mr. Justice Crompton remarked more extensively in the Jefferys case:

“It was held in Clementi v. Walker, on perfectly satisfactory grounds, as is plainly to be collected from the statute, that by the first publication is meant a publication in this kingdom,—and the main question in the present case is, whether the right to acquire the monopoly by a bond fide first publication here, is confined to persons who are British subjects either by birth or Act of Parliament, or as owing temporary allegiance here by virtue of their residence in this country. In Clementi v. Walker no such restriction as is now contended for appears to have at all entered into the contemplation of either the Bar or the Court. Such a doctrine would have been at once decisive of the cause, and would have rendered it unnecessary for the Judges to consider the question on which they decided. In deciding that a prior publication abroad by a foreign author, not followed up by a publication here in a reasonable time, destroyed any right in the foreign author, and in doubting what would be the effect of such prior publication abroad, if followed up by a publication here within a reasonable time, the Court of King’s Bench seems rather to have recognised the general right of a foreign author to become the first publisher here within the statutes, than to have supposed such right to be confined to British authors publishing here.”

Mr. Justice Crompton also stated:

“I do not find any thing which is sufficiently clear to satisfy me that the Legislature has expressed any intention to restrict the protection given, further than as decided in the case of Clementi v. Walker, that the statute must be considered as legislating upon what is really a British publication; and I think that, provided the publication is really and bond fide British, the copyright may be acquired, although the author is foreign, although he resides abroad, and although he does not personally come to England to publish. I come to this opinion on the words of the statute, vesting the right in the authors or their assigns from the first publication; and from not finding any thing in the Acts to exclude friendly foreigners from its advantage.”

As pointed out by Mr. Justice Williams, in 1835 the law was changed (in the case of D’Almaine v. Boosey (4 Younge & C. Exch. 424)), such that copyright could not be gained by a foreign author who was resident abroad at the time of the publication. See 4 H.L.C. at 859-860. (The Jefferys case was decided under the Copyright Act of 1842 and under that act made clear that non-resident foreigners obtained no copyright within the realm. Earlier it had not been so.) Therefore, Mr. Geisner’s statement that in 1830 “only British subjects could hold copyright in Canada” must yield to the very clear dictates of English law, which hold the opposite. And that law did not change with the adoption of the Copyright Act of 1842, for in the 1854 case of Routledge v. Low (4 H. L. C. 815), the court held that a foreign author who was resident even for a few days in Canada, having gone there expressly for the purpose of acquiring copyright while her book was published in London, nevertheless was an author within the Act, whose literary work could qualify for copyright protection, a proposition which had not been disputed in Jefferys v. Boosey.

CONCLUSION

It appears quite clear that the revelation’s command “ye shall go to Kingston” and the revelation’s announcement of a grant unto the Prophet of “a privelige that he may sell a copyright” through Oliver Cowdery, Joseph Knight, Hiram Page and Josiah Stowell “for the four Provinces” are a command and announcment wholly consistent with the historical and legal context: the literary resources were available in Kingston, the legal context justified the mission, and the historical context is consistent with the revelation. To the extent that any legal research is needed to ascertain whether it was or “wasn’t even possible to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it” (Mr. Bradley’s words), whether “copyrights could be secured in Kingston” (Mr. Bradley’s words), and whether “only British subjects could hold copyright in Canada” (Mr. Geisner’s words), it would seem that the answers are clear: a copyright could be secured in Kingston (and, of course, it could be sold there, as the revelation gave the Prophet a “privelige” to do), and this all could be accomplished notwithstanding the Prophet was not a British citizen and perhaps also notwithstanding he personally was not there at the time of sale (he could have made plans to be there at the time of printing or publication or both, later). In short, the revelation is entirely consistent with history, law, and religious principles (meaning the conditional nature of the revelation—“if ye do this”; “if the People harden not their hearts”; “if ye are faithful”).

Well done Mr. Ehat! I hope you will publish your findings.

Stephen, unlike a few others, I found that your comments were not “gobbledygook” at all, they were very interesting and directly relevant to the conversation. Well done.

I’d like to address Mr. Ehat’s argument that it was possible for Joseph Smith to obtain a copyright for Canada in 1830. Mr. Ehat asserts that in 1830 the Statute of Anne was the legislation that governed “England (and in its Dominions, including Upper Canada),” writing:

“And insofar as concerns the question posed by Mr. Bradley here in this blog, the two salient, important features of copyright law in existence in the realm in 1830 were these: (1) copyright and its duration in England (and in its Dominions, including Upper Canada) was governed by the Statute of Anne…”

And yet, I discover that:

“The original Copyright Act (the 8 Anne, c. 19) protected copyright throughout Great Britain. The 43 Geo. 3, c.107 (1843), extended this protection over the whole of the United Kingdom and the British dominions in Europe. The 54 Geo. 3, c. 156 (1854), extended the protection still further over the whole of the British dominion.”

ref: The Canada Law Journal, Volume 4, 1868 p231

http://tinyurl.com/yja8mq2

So, contrary to Mr. Ehat’s assertion, British copyright laws did *not* apply in Canada in 1830. And there was no Canadian copyright law enacted until 1832.

I will note correlating evidence gleaned from several histories:

===

“There were territorial loopholes in the 1710 Act. It did not extend to all British territories, but only covered England, Scotland and Wales.

…

Many reprints of British copyright works were consequently issued both in Ireland and in North American colonies, without any license from the copyright holder required.

…

The Irish also made a flourishing business of shipping reprints to North America in the 18th century. Ireland’s ability to reprint freely ended in 1801 when Ireland’s Parliament merged with Great Britain, and the Irish became subject to British copyright laws.”

===

In light of this, what copyright could have been obtained in Canada in 1830 that could have been sold to anyone that would have granted them exclusive rights to publish and sell the Book of Mormon in Canada?

The link supplied by Mr. RetroProphet, given to provide the reader of this blog with a source for his first quotation, is a link that leads the reader to page 238 of the September 1868 issue of “The Canada Law Journal” (Vol. 4, N. S.). That month the Journal printed the 1868 opinion of the House of Lords in the case of Routledge v. Low. That case was decided under the Copyright Act of 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c. 45). Mr. RetroProphet’s quotation is not found on the page to which he links the reader (page 238), even though that page is the one he expressly cites to in the text of his blog contribution. Rather, when one reads the entire report — including the statement of facts on pages 229-230, the arguments of counsel for the appellants on page 230, the arguments of counsel for the respondents on page 230, and the opinion of the Lord Chancellor on pages 230-232, the opinion of Lord Cranworth on pages 232-233, the opinion of Lord Chemlsford on pages 233-234, the opinion of Lord Westbury on pages 234-235, and the opinion of Lord Colonsay on page 235) — one finds Mr. RetroProphet’s quotation to be a quotation taken from page 231 (part of the opinion of the Lord Chancellor), not from page 238 (part of the opinion of Lord Chelmsford).

Mr. RetroProphet’s quotation is as follows: “The original Copyright Act (the 8 Anne, c. 19) protected copyright throughout Great Britain. The 43 Geo. 3, c.107 (1843), extended this protection over the whole of the United Kingdom and the British dominions in Europe. The 54 Geo. 3, c. 156 (1854), extended the protection still further over the whole of the British dominion[s].”

I note, however, that there is one difference from the text as originally penned by the Lord Chancellor and as “quoted” by Mr. RetroProphet. That difference is the parenthetical “(1854)”. That parenthetical is not in the original. It has been supplied by Mr. RetroProphet. And, it so happens, it is wrong. If there is to be any parenthetical attached to a citation to “54 Geo. 3, c. 156” it should be “1814,” not “1854.” “54 Geo. 3, c. 156” is a citation for the amendment of the Statute of Anne that was enacted in 1814, not in 1854. See, e.g., Justin Hughes, “Copyright and Incomplete Historiographies: Of Piracy, Propertization, and Thomas Jefferson” (Southern California Law Review, vo. 79, pp. 993 et seq., 2006), Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper No. 166. If Mr. RetroProphet had read, for example, the Clementi v. Walker opinion (issued in 1824) (cited above, in this blog) he might have noticed that that 1824 opinion cites to “54 Geo. 3, c. 156,” enacted in 1814, and not in 1854, thirty years after Clementi.

And, specifically, what does 54 Geo. 3, c. 156 provide? Section 4 of the “British Act to Amend the several Acts for the Encouragement of Learning” (1814) 54 Geo. 3 c. 156, clarified that copyright was infringed where “any bookseller or printer, or other person whatsoever, in any part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in the Isles of Man, Jersey or Guernsey, or in any other part of the British dominions, shall ‘print, reprint or import’ any such book or books.”

And just by way of cautionary note, in case Mr. RetroProphet wants to glean legal information from periods other than 1830, it should be noted that when one is researching what the law was in 1830, one must not be influenced by what the law was in 1842 and later. For example, in Graves v. Gorrie, 3 Ont. L. 697, 699 [dism app 1 Ont. L. 309 (dism app 32 ont. 266, and app dism [1903] A. C. 496, the following is explained (contradicting Mr. RetroProphet’s assertion):

“The original copyright Act, 8 Anne ch. 19, protected the copyright in books granted by that Act throughout Great Britain only. The Act, 41 Geo. III, ch. 107 (Imp.), extended the area of protection throughout the whole of the United Kingdom and the British dominions in Europe; and the Act, 54 Geo. III, ch. 156 (Imp.), extended the area of protection over the whole of the British dominions. These Acts were repealed by the Act 5 & 6 Vict. ch. 45 (Imp.), which by sec. 29 provided that it should extend to Great Britain and Ireland, and to every part of the British dominions.”

I happily join ranks with those who have a penchant to add parentheticals, and here add my own, so as to make the above quotation meaningful:

41 Geo. III, ch. 107 (1801)

54 Geo. III, ch. 156 (1814)

5 & 6 Vict. ch. 45 (1842)

Mr. RetroProphet, perhaps, has a conclusion in mind and wants his “quotation” to support that conclusion. That is the only impetus I can perceive in his having chosen to add a parenthetical to the quotation and to have chosen to use the year “1854” inside his parenthetical.

Mr. RetroProphet’s second quotation (“There were territorial loopholes in the 1710 Act. It did not extend to all British territories, but only covered England, Scotland and Wales”) comes from George Johnson, “A Brief History of Copyright Law,” in “The Active Author’s Copyright Compendium,” Vol. 1 (ResearchCopyright.com, n.d.), page 10. Anyone who reads Mr. Johnson’s “Brief Hisotry” will note not only that he covers the history of copyright from the 1300s to the 1880s in a mere three pages (!), but also that he jumps (necessarily) directly from 1801 to 1886, blowing right past 1814, without mention of 54 Geo. III, ch. 156. Mr. Johnson is neither a historian nor an attorney. Mr. Johnson’s “Brief History,” indeed, is quite brief (and when used as a source to discuss what copyright law was in Canada in 1830, his write up is simply and wholly inadequate).

Mr. RetroProphet’s third quotation (“Many reprints of British copyright works were consequently issued both in Ireland and in North American colonies, without any license from the copyright holder required”) comes from that same page in that same source. The quotation pertains to the 1700s and deals with the well-known practice of reprints. The quotation is inapposite and beside the point.

Mr. RetroProphet’s fourth quotation (“The Irish also made a flourishing business of shipping reprints to North America in the 18th century. Ireland’s ability to reprint freely ended in 1801 when Ireland’s Parliament merged with Great Britain, and the Irish became subject to British copyright laws”) also comes from that sames source, page 11. That quotation, too, is inapposite and beside the point.

Mr. RetroProphet, no doubt, will look for other items to prove his point (or perhaps some other point). We await.

Well, that was a rookie error, wasn’t it? I apologize to Mr. Ehat and thank him for his tutorial.

Mr. Geisner and Mr. RetroProphet have raised helpful questions that help refine the dialogue on the issues raised. Mr. RetroProphet remarkably apologizes for what he calls “a rookie error.” Well, “rookie” or not, that’s the sign of a mature person to make a public acknowledgement of error. To the extent that I can accept the apology on behalf of other readers, apology accepted; no offense taken.

Indeed, to round out the discussion and correct some misstatements I myself made above, misstatements that divert from a refined view of 1830 copyright law applicable to Canada, allow me to enumerate the following, to amend what is said above and to make the discussion complete:

1. In my October 16, 2009 post, I could have stated my point more accurately as follows: “We should be dealing only with, as the revelation itself states, the ability to sell a copyright in Kingston, not the obtaining of a copyright in that specific place.” My prior use of the word “the” could be confused as a reference to a sale of the American copyright, which was not my intention nor the direction of the conversation. I thought it would be good to clarify that here. (I repeat the error a few more times (see below)), so I attempt below also to identify and correct those here, too.)

All my other musings in that October 16, 2009 post are pretty much useless musings except for the bottom-line point (which, again, should be worded as follows, changing the “the” to an “a” to make it read “sell a copyright”): “The way the Prophet sought to protect his and the Church’s interest in the rights to publishing the Book of Mormon was essentially the only way: sell a copyright to a publisher in Canada.” That would entail obtaining a copyright anywhere in Upper Canada and attempting to sell it in Kingston.

2. Joe Geisner referred to my first post as “gobbledygook.” He’s right. I’m an attorney. I can’t help myself.

3. In my October 17, 2009 post, I misspoke as follows: “Putting aside the point about the difference between obtaining the copyright in Canada and selling it there, when one looks for the reason why the Prophet would look to sell his American copyright [sic] in Canada, one must wonder if it indeed had any value there; in other words, the question ought to be whether the Prophet’s and the Church’s American copyright [sic] could be recognized (i.e., have value) in Canada. You and Mr. Bradley would say ‘no’; I would say ‘yes.'” I can’t believe I said that; the discussion was not yet about reciprocity (recognition in Canada of an American copyright, so I should not have broached that subject). My statment should have been written as follows: “Putting aside the point about the difference between obtaining a copyright in Canada and selling it there, when one looks for the reason why the Prophet would look to sell in Kingston a newly-obtained Canadian copyright to his book being contemporaneously copyrighted in America, one must wonder if it (a Canadian copyright) indeed would have any value there; in other words, the question ought to be whether the Prophet’s and the Church’s American copyrighted book could be recognized with a copyright obtained in Canada that could have value in Canada. You and Mr. Bradley would say ‘no’; I would say ‘yes.'” That is a more refined statement of the legal issue posed by Messrs. Bradley, Geisner and RetroProphet, for it raises the issue (answered by the statutes and cases) of whether in 1830 an American who publishes a book in America can simultaneously obtain a copyright under the laws applicable in Canada in order to publish the book in a protected way in the four provinces. That answer, of course, is “yes.”

I was also similarly imprecise later in that same posting: the text of the revelation speaks of the sale of a copyright (meaning a Canadian copyright, not the American copyright), and the obtaining of a copyright everywhere, presumably including also a copyright in Canada and the attempt to sell in Kingston such a copyright. The real issue was not, as I stated, “Did the American copyright have value in Canada?” (we were not talking about reciprocity) but, rather, did the Prophet’s emissaries have the ability, under the law applicable at the time, to obtain in Upper Canada (or anywhere in one of the four provinces) a copyright enforceable in the four provinces even though the book already was about to be published in America pursuant to the registration of a copyright in America?

The conclusion made in my October 17 post, nonetheless, remains valid: An American, at the time (early 1830), could indeed go to Canada (anywhere) and publish his work there (anywhere) and indeed be protected by the copyright laws applicable in Canada (without being a citizen or even a resident) and thus, by selling a copyright to one publisher in Canada (e.g., in Kingston or, for that matter, anywhere in Canada), he would allow that one Canadian publisher thereby to be entitled to exclude other Canadian publishers from profiting from publishing the work. On this point one must remember that the statement in Hiram Page’s letter, to the effect that the copyright could not be sold in Kingston, apparently results from his misunderstanding; the sale could take place anywhere (for a copyright is intangible personal property). If someone in Kingston actually did tell Page that no one in Kingston was “authorized” to buy a copyright that would protect the book in the four provinces, that someone was wrong. No one needs to be “authorized” to buy a copyright; the purchaser can purchase a copyright and then do whatever is necessary to publish the book. It may, in fact, be that the people in Kingston showed an air of respect for the emmisaries and told them they could not buy a copyright there but that may have been a polite way of saying “get lost, we want nothing to do with your Book of Mormon.”

4. In my October 20, 2009 post, I present for the first time the first results of any actual legal research on the question posed (even though not accurately stated in the prior posts). In that post, I quote Mr. Bradley, who states both that Hiram Page “notes that there was no way to secure the copyright at Kingston, as they had been sent to do” [the revelation speaks of selling it there, not securing it there] and that “the real issue with the revelation was not that the sale did not occur but that it (reportedly) wasn’t even possible to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it” [same]. From that point forward, the discussion deals with legal questions (as framed by Mr. Bradley): “Was it even possible (legally) to secure a copyright at the place they’d been sent to do it?” and “What was the law of the time?” The balance of that post presents legal research to support the conclusion that indeed in 1830 a copyright could, indeed, be obtained in Upper Canada for a work published in America. And of course intangible personal property could be sold in Kingston as well as in any other place and no “authorization” was necessary for a buyer to complete such a transaction.

5. Mr. RetroProphet’s October 23, 2009 post attempted to quote (albeit inaccurately but nonetheless, for our purposes, helpfully) from a case I had cited in my October 20, 2009 post (Mr. RetroProphet misquoting it as follows: “The original Copyright Act (the 8 Anne, c. 19) protected copyright throughout Great Britain. The 43 Geo. 3, c.107 (1843), extended this protection over the whole of the United Kingdom and the British dominions in Europe. The 54 Geo. 3, c. 156 (1854), extended the protection still further over the whole of the British dominion.”) The anture of the misquotation is the addition of two, not one, parentheticals after two, not one, citations. I probably could have also pointed out that the citation to “43 Geo. 3, c. 107” should not have had a parenthetical added (“(1843)”) and, to boot, I probably should have clarified that the citation itself (that Mr. RetroProphet otherwise correctely quoted from the printed source material (“43 Geo. 3, c.107”) was erroneous in the original and all subsequent reports of the Lord Chancellor’s opinion. That citation actually should be “41 Geo. 3, c. 107” (and, of course, if there was to be any parenthetical after that citation, it would be “(1801),” as otherwise was clear from the balance of my discussion). That’s a small point, but when citing cases, it’s important for discussion to be accurate.

So I actually should have said the following, to be complete and accurate: “I note, however, that there are two differences from the text as originally penned by the Lord Chancellor and as ‘quoted’ by Mr. RetroProphet. Those differences are the parentheticals ‘(1843)’ and ‘(1854)’. Those parentheticals are not in the original. They have been supplied by Mr. RetroProphet. And, it so happens, the both are wrong. If there are to be any parentheticals attached to the citations to ’43 Geo. 3, c. 107′ and ’54 Geo. 3, c. 156′ they should be, respectively, ‘(1801)’ and ‘(1814),’ not ‘(1843)’ and ‘(1854).’ ’43 Geo. 3, c. 107′ is actually a typographical error that appears both in the original case report and in all subsequent reprints of that case report (including in the Canada Law Journal from which Mr. RetroProphet quotes; it should have read ’41 Geo. 3, c. 107′ and if there were to be any parenthetical appended to it, it would be ‘(1801).’ And ’54 Geo. 3, c. 156′ is a citation for the amendment of the Statute of Anne that was enacted in 1814, not in 1854. See, e.g., Justin Hughes, ‘Copyright and Incomplete Historiographies: Of Piracy, Propertization, and Thomas Jefferson’ (Southern California Law Review, vol. 79, pp. 993 et seq., 2006), Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper No. 166. If Mr. RetroProphet had read, for example, the Clementi v. Walker opinion (issued in 1824) (cited above, in this blog) he might have noticed that that 1824 opinion cites to ’54 Geo. 3, c. 156,’ enacted in 1814 (not in 1854, thirty years after Clementi).”

My suspicion is that when Hiram Page stated in his 1848 letter to McLellin that “there was no purchaser” in Kingston, he was right (at least to the extent that he meant there was no willing purchaser). Clearly, there were publishers in Kingston (see my October 20 post). And my suspicion also is that when Hiram Page stated in that letter that no one was “authorized at Kingston to buy rights for the province” and that “little York was the place where such business had to be done,” he probably was merely reporting the thanks-but-no-thanks reception the emmisaries received, not an accurate reflection of what the law allowed.

“emissaries” (twice misspelled).

Stephen Ehat,

I apologize for my tardiness in responding to the discussion.

Thank you very much for the thoughtful and informative comments. You have advanced the discussion further than I believed possible and I would like to thank you for this. The research you have provided should help in our understanding of copyright in Canada. Again thank you for this work and the time you have spent researching this subject.

Personally I have a bit different take on the court rulings, but it appears nothing is as clear cut as one would hope.

Again, thank you for taking the time to present the information in the Clementi v. Walker case. I hope we can continue the discussion as further information becomes available.

Regarding Hiram Page’s 1848 account of the trip to Canada, I wonder why he drew a distinction between the fact that “there was no purchaser” and *also* (note his “neither”) that among those they spoke to, no one was “authorized at Kingston to buy rights for the Provence.”

If both statements referred identically to a deal whereby a Canadian publisher would buy rights to publish an edition for Canada, “there was no purchaser” appears to be redundant with “buy(ing) rights for the Provence” — perhaps the latter statement in actuality was the response to a question other than merely “Would you like to purchase the rights to publish this book?”

Perhaps after Smith’s men received an expression of no interest on the part of a Kingston publisher, they asked, “Well, would you be able to arrange for us to register a copyright for the Provence?” After all, they had been told to secure the copyright, and perhaps had in mind registering a copyright for the provinces absent a sale, and in advance of publication, precisely as Smith had done previously in the United States.

I’d like to suggest the possibility that “neither were they authorized at Kingston to buy rights for the Provence; but little York was the place where such business had to be done.” referred to the question of how a copyright needed to be registered. Considering that York was the seat of government for Upper Canada, perhaps anybody who wished to file the necessary paperwork, whether it was a Canadian publisher or an American, needed to do so at government offices in York.

Submitted for consideration, with all due humility, of course.

Has anyone considered the broader question of why an all-powerful God, presumably capable of protecting his own work by his own power, would even need to secure a copyright in the first place? It seems uncharacteristic of God rely upon man-made laws governing possession for his own protection. I can think of no reason why God would need a copyright, but I can think of many reasons why men would want it. I don’t fault any man for wanting to secure a copyright for the work; what I question is why a revelation was even needed for this action.

Scott, God isn’t ruling on the earth right now, otherwise a lot of bad things that have happened and are happening would not have happened or be happening. We have to live under man’s laws.

Stephen,

I just became aware of your responses to my questions and wanted to make a few comments.

First, thank you for providing some legal context. Although I find it odd that you state that such context is not necessary as you provide it, I appreciate the effort you took to provide it.

Second, please cite my comments as being from the Mormon Apologetics and Discussion Board on which I posted them, rather than the Mormon Research Ministry site that has appropriated them from that board.

Third, in light of MRM’s use of *part* of my MAD posting, I’d like to point out that my comments on the board end by giving my view of how the Canadian copyright revelation can be viewed as divine in origin *even if* legal research *were* to show that the copyright business legally could not be done in Kingston–i.e., I don’t see Joseph Smith’s prophethood being at stake over the issue.

Fourth, I think you have offered research that suggests the scenario I had in mind–that of needing to secure a legal copyright before selling rights of publication–may simply be wrong, which would change the issues at hand considerably. However, given the admittedly provisional nature of your research, I believe the legal questions surrounding the revelation remain open and will continue to unless or until someone (perhaps you) does a detailed study on the matter.

Fifth, I think the records left to us suggest that the participants in this event did believe there was a legal requirement to transact copyright business in Toronto. When Page says that the “business” of “buying rights for the province” “had to be done” at Little York, I can’t help seeing this as referring to a legal issue and not simply failure to sell. It would not follow from the mere absence of buyers in Kingston that the sale “had to be done” in Little York, or in any other *particular* place. In that case, buyers might be found anywhere, and not in Little York only. Thus, so far as I can see, Page is referring to something other than an absence of buyers: he *believes* there is a law requiring the business to be transacted in Little York. The editors of the revelation appear to similarly believe something was amiss with the revelation sending them to Kingston, or so the pattern of their edits would suggest–as I laid out on MAD.

Perhaps there was no legal requirement to transact the business at Toronto, but persons in Kingston told the sellers that there was. These persons could have purposely misled them, in which case they would indeed have been “hardening their hearts.”

However, I would incline away from such a conclusion unless I were quite certain about the applicable law. The officials and printers with whom I must assume Page, Cowdery, Knight, and Stowell spoke should have understood copyright law in their province. And it seems to me highly unlikely that disparate individuals colluded to mislead these strangers who came to them to sell rights to a book.

So, unless or until I see legal scholarship nailing down the applicable law of that place and time, I would incline toward believing the stated opinion of those with whom Page, et al. spoke–that the business he and the others sought to transact could only be done at Little York.

Perhaps an adequate legal study will be done on the issue. Perhaps not. But whichever way the legal evidence comes out–if it ever gets adequately sorted out, I’m satisfied that Joseph Smith’s prophethood does not stand or fall on this issue.

Don

http://preview.tinyurl.com/yg6kj4z