FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Home > Book of Abraham Sandbox > Joseph Smith's "Incorrect" Translation of the Book of Abraham Papyri > The Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham > Approaching the Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham

| This page is still under construction. We welcome any suggestions for improving the content of this FAIR Answers Wiki page. |

Summary: Joseph Smith's explanations of the Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham pose a conundrum for faithful students of the Book of Abraham: scholars of the Book of Abraham have no agreed-upon method for interpreting the explanations. Scholars Stephen O. Smoot, John Gee, Kerry Muhlestein, and John S. Thompson have outlined various approaches in an article for BYU Studies Quarterly, and this page summarizes their work.[1]

This approach suggests that we interpret the explanations by looking at how Egyptians in Abraham’s day, or Abraham himself, would have understood them. This approach is certainly the most straightforward way of approaching the Facsimiles. However, it is severely complicated by the fact that the Joseph Smith Papyri (the papyri that is extant today) dates to the Ptolemaic Period of Egyptian history.

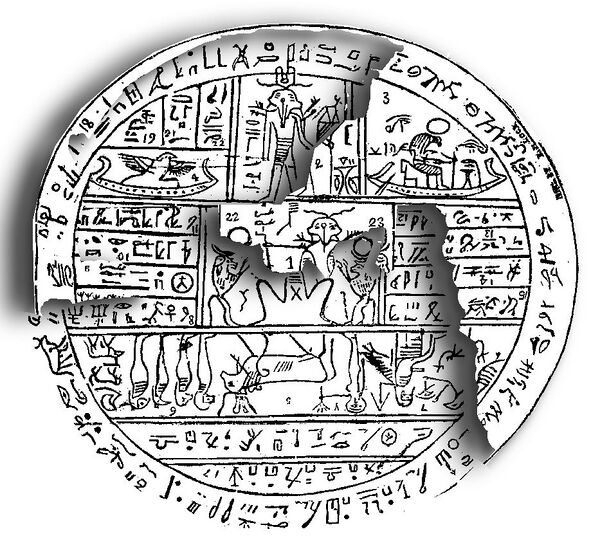

Furthermore, hypocephali (like the one depicted in Facsimile 2) were not in use in Egypt until the Late Period lasting from 664 BC to 332 BC. This is long after Abraham is traditionally thought to have lived.

This approach suggests that the illustrations we have, as preserved in the facsimiles, are much later and altered copies of Abraham’s originals. To interpret them, we should consider the underlying Abrahamic elements and compare them with the Egyptians' understanding of these images.[2] This approach avoids some of the potential pitfalls of the first approach, but is complicated by the search for similar artwork that dates to the time of Abraham that was then altered by a sequence of later, Egyptian redactors.

This is the approach suggested by Dr. John Gee, a Latter-day Saint Egyptologist.[3] This approach can account for some but not all of the evidence that supports Joseph Smith's explanations.

This is the approach taken by Dr. Kerry Muhlestein, another Latter-day Saint Egyptologist.[4] This approach can also account for some but not all of the evidence that supports Joseph Smith's explanations.

This approach is taken by Kevin Barney, a Latter-day Saint scholar and apologist.[5] Barney's approach can likewise support some but not all of the evidence for Joseph Smith's explanations.

We can make sense of Joseph’s interpretations by expanding our understanding of his role as a “translator.” This approach is taken by Terryl L. Givens, a Latter-day Saint theologian, literary scholar, and historian.[6]

This approach is complicated by the fact that Joseph Smith's explanations are, in many instances, consistent with how ancient people would have interpreted the same figures. Also, Joseph Smith seems to be pulling his explanations from the ancients themselves when he says things like "[o]ne day in Kolob is equal to a thousand years according to the measurement of this earth, which is called by the Egyptians Jah-oh-eh" (Fac. 2, Fig. 1). Thus, clearly Joseph Smith is not merely depicting his revealed text with the Facsimiles.

This is the most recently-articulated approach, espoused by Dr. John Thompson: another Latter-day Saint Egyptologist.[7] Thompson's theory is promising, but further investigation is necessary to validate its utility.

This is the approach preferred by our critics. The problem with their theory is that, in many instances, Joseph Smith's explanations have significant resonance or, in other cases, perfect resonance with how the ancients would have understood the same figures. There is simply no way Joseph Smith would have been able to get so many things right about his explanations.

Regardless of the approach one uses, they will eventually encounter problems. With our commentary on the Facsimiles, FAIR has attempted to provide a broad range of considerations about the ancient world that will enable readers to assess the level of resonance Joseph Smith's explanations hold with the ancient world. However, it should be kept in mind that the level of support for Joseph Smith's explanations is, in some cases, dependent on how one interprets the explanation.

Joseph Smith's explanations of the Facsimiles can be interpreted in different ways. Depending on how one interprets the explanations, the support for the explanation can become weaker or stronger.

Facsimile 2 is a particular kind of document. It is a copy of what is known as a hypocephalus.

Before we proceed with our commentary on Joseph Smith's explanations of Facsimile 2, there is a point that should be kept in mind.

The original hypocephalus was missing large portions when Joseph Smith originally received it. This is confirmed by a sketch of the hypocephalus that was likely done by Willard Richards.

The missing parts of the hypocephalus correspond to Figures 1, 3, 12, 13, 14, and 15. Those portions are highlighted portions of Facsimile 2.

Figure 1 may have had its heads restored by comparison to and copying of Figure 2.

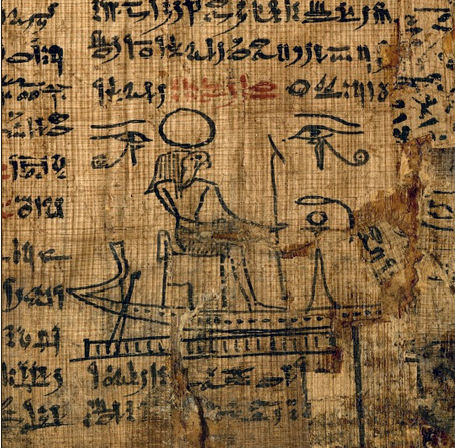

Figure 3 appears to have been taken from Joseph Smith Papyri IV (see the bottom right corner of the papyrus, depicted below).

Figures 12–15 were taken from Joseph Smith Papyri XI. It is because of the removal of characters from JSP XI to the hypocephalus that the translation of these characters renders nonsense in the context of the hypocephalus.

Some question whether it could be a legitimate practice to "replace" several figures of the hypocephalus with figures from other papyri fragments. We'd argue "yes" for two reasons:

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now