FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

m (RogerNicholson moved page Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Index/Preface to Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Preface) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{FairMormon}} | {{FairMormon}} | ||

{{H1 | {{H1 | ||

|L=Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy | |L=Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Preface | ||

|H=Response to claims made in "Preface" | |H=Response to claims made in "Preface" | ||

|T=[[../../|Nauvoo Polygamy: "... but we called it celestial marriage"]] | |T=[[../../|Nauvoo Polygamy: "... but we called it celestial marriage"]] | ||

|A=George D. Smith | |A=George D. Smith | ||

| Line 10: | Line 8: | ||

|>=[[../Chapter 1|Chapter 1]] | |>=[[../Chapter 1|Chapter 1]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

<onlyinclude> | |||

{{H2 | |||

|L=Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Preface | |||

|H=Response to claims made in Nauvoo Polygamy, "Preface" | |||

|S= | |||

|L1= | |||

}} | |||

</onlyinclude> | |||

==Quick Navigation== | ==Quick Navigation== | ||

*[[Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Index/Preface#Response to claim: flyleaf - The book claims that Bishop Edwin Woolley married a plural wife without having her first divorce her legal husband|Response to claim: flyleaf - The book claims that Bishop Edwin Woolley married a plural wife without having her first divorce her legal husband]] | *[[Criticism of Mormonism/Books/Nauvoo Polygamy/Index/Preface#Response to claim: flyleaf - The book claims that Bishop Edwin Woolley married a plural wife without having her first divorce her legal husband|Response to claim: flyleaf - The book claims that Bishop Edwin Woolley married a plural wife without having her first divorce her legal husband]] | ||

A FAIR Analysis of: Nauvoo Polygamy: "... but we called it celestial marriage", a work by author: George D. Smith

|

Chapter 1 |

The book claims that Bishop Edwin Woolley married a plural wife without having her first divorce her legal husband.

Author's sources:

- No source provided

Gregory L. Smith, A review of Nauvoo Polygamy:...but we called it celestial marriage by George D. Smith. FARMS Review, Vol. 20, Issue 2. (Detailed book review)

"Plural Marriage and Families in Early Utah," Gospel Topics on LDS.org:

Church leaders recognized that plural marriages could be particularly difficult for women. Divorce was therefore available to women who were unhappy in their marriages; remarriage was also readily available.[1]

Some members of the Church remarried without obtaining a formal legal divorce. Was this adultery? Remarriage without a formal, legal divorce was the norm for the period, especially on the frontier and among the poor. These were the legal realities faced by nineteenth century Americans.

"Presentism" is an analytical fallacy in which past behavior is evaluated by modern standards or mores. Even worse than a historian's presentism is a historian exploiting the presentism of his readers. Critics do this repeatedly when they speak about legal issues. "Presentism," observed American Historical Association president Lynn Hunt, "at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior. . . . Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards." [2]

Louisa Rising married Edwin Woolley "without first divorcing her legal husband," the dust jacket of George D. Smith's Nauvoo Polygamy teases. We are reminded later that "though she was not divorced from her legal husband, she agreed to marry" (p. 345). Eleanor McLean also married Parley Pratt without divorcing her first husband. It appears that G. D. Smith hopes to capitalize on ignorance about nineteenth-century laws and practices regarding marriage and divorce. "From the standpoint of the legal historian," wrote one expert who is not a Latter-day Saint, "it is perhaps surprising that anyone prosecuted bigamy at all. Given the confusion over conflicting state laws on marriage, there were many ways to escape notice, if not conviction." [3] To remarry without a formal divorce was not an unusual thing in antebellum America.

Bigamy or, rather, serial monogamy (without divorce or death) was a common social experience in early America. Much of the time, serial monogamists were poor and transient people, for whom the property rights that came with a recognized marriage would not have been much of a concern, people whose lives only rarely intersected with the law of marriage. [4]

The Saints were often poor and spent most of their time on the frontier, where the legal apparatus of the state was particularly feeble. Women who had joined the church and traveled to Zion without their husbands were particularly likely to be poor, and also unlikely to be worried about property rights. Nor, not incidentally, were their husbands available for a formal divorce.

Does this mean that marriage in America was a free-for-all? Hardly, notes Nancy Cott:

When couples married informally, or reversed the order of divorce and remarriage, they were not simply acting privately, taking the law into their own hands. . . . A couple about to join or leave an intimate relationship looked for communal sanction. The surrounding local community provided the public oversight necessary. Without resort to the state apparatus, local informal policing by the community affirmed that marriage was a well-defined public institution as well as a contract made by consent. Carrying out the standard obligations of the marriage bargain—cohabitation, husband's support, wife's service—seems to have been much more central to the approbation of local communities at this time than how or when the marriage took place, and whether one of the partners had been married elsewhere before. [5]

It also should be remembered that because Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Latter-day Saint leaders exercised exclusive jurisdiction over celestial or plural marriages, marriages conducted under their supervision had as much (or more) formal oversight as many traditional marriages in America during the first half of the nineteenth century. Critics of the Church offer us none of this information or perspective—with the result that some readers might be horrified by the "loose" marriage practices of the Saints.

Some critics of Mormonism like to emphasize that some LDS members did not receive civil divorces before remarrying—either monogamously or polygamously. They either state or imply that this shows the Saints' cavalier attitude toward the law.

The Saints were often poor and spent most of their time on the frontier, where the legal apparatus of the state was particularly feeble. Women who had joined the church and traveled to Zion without their husbands were particularly likely to be poor, and also unlikely to be worried about property rights. Critics usually tell us nothing of all this—with the result that some credulous readers might be horrified by the "loose" marriage practices of the Saints. It also should be remembered that because Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Latter-day Saint leaders exercised exclusive jurisdiction over celestial or plural marriages, marriages conducted under their supervision had as much (or more) formal oversight as many traditional marriages in America during the first half of the nineteenth century.

"From the standpoint of the legal historian," wrote one expert who is not a Latter-day Saint, "it is perhaps surprising that anyone prosecuted bigamy at all. Given the confusion over conflicting state laws on marriage, there were many ways to escape notice, if not conviction." [6]

Bigamy or, rather, serial monogamy (without divorce or death) was a common social experience in early America. Much of the time, serial monogamists were poor and transient people, for whom the property rights that came with a recognized marriage would not have been much of a concern, people whose lives only rarely intersected with the law of marriage. [7]

Nor, not incidentally, were their husbands available for a formal divorce.

Does this mean that marriage in America was a free-for-all? Hardly, notes Nancy Cott:

When couples married informally, or reversed the order of divorce and remarriage, they were not simply acting privately, taking the law into their own hands. . . . A couple about to join or leave an intimate relationship looked for communal sanction. The surrounding local community provided the public oversight necessary. Without resort to the state apparatus, local informal policing by the community affirmed that marriage was a well-defined public institution as well as a contract made by consent. Carrying out the standard obligations of the marriage bargain—cohabitation, husband’s support, wife’s service—seems to have been much more central to the approbation of local communities at this time than how or when the marriage took place, and whether one of the partners had been married elsewhere before. [8]

Critical sources |

|

"Plural Marriage and Families in Early Utah," Gospel Topics on LDS.org:

Church leaders recognized that plural marriages could be particularly difficult for women. Divorce was therefore available to women who were unhappy in their marriages; remarriage was also readily available.[1]

Some members of the Church remarried without obtaining a formal legal divorce. Was this adultery? Remarriage without a formal, legal divorce was the norm for the period, especially on the frontier and among the poor. These were the legal realities faced by nineteenth century Americans.

"Presentism" is an analytical fallacy in which past behavior is evaluated by modern standards or mores. Even worse than a historian's presentism is a historian exploiting the presentism of his readers. Critics do this repeatedly when they speak about legal issues. "Presentism," observed American Historical Association president Lynn Hunt, "at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior. . . . Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards." [2]

Louisa Rising married Edwin Woolley "without first divorcing her legal husband," the dust jacket of George D. Smith's Nauvoo Polygamy teases. We are reminded later that "though she was not divorced from her legal husband, she agreed to marry" (p. 345). Eleanor McLean also married Parley Pratt without divorcing her first husband. It appears that G. D. Smith hopes to capitalize on ignorance about nineteenth-century laws and practices regarding marriage and divorce. "From the standpoint of the legal historian," wrote one expert who is not a Latter-day Saint, "it is perhaps surprising that anyone prosecuted bigamy at all. Given the confusion over conflicting state laws on marriage, there were many ways to escape notice, if not conviction." [3] To remarry without a formal divorce was not an unusual thing in antebellum America.

Bigamy or, rather, serial monogamy (without divorce or death) was a common social experience in early America. Much of the time, serial monogamists were poor and transient people, for whom the property rights that came with a recognized marriage would not have been much of a concern, people whose lives only rarely intersected with the law of marriage. [4]

The Saints were often poor and spent most of their time on the frontier, where the legal apparatus of the state was particularly feeble. Women who had joined the church and traveled to Zion without their husbands were particularly likely to be poor, and also unlikely to be worried about property rights. Nor, not incidentally, were their husbands available for a formal divorce.

Does this mean that marriage in America was a free-for-all? Hardly, notes Nancy Cott:

When couples married informally, or reversed the order of divorce and remarriage, they were not simply acting privately, taking the law into their own hands. . . . A couple about to join or leave an intimate relationship looked for communal sanction. The surrounding local community provided the public oversight necessary. Without resort to the state apparatus, local informal policing by the community affirmed that marriage was a well-defined public institution as well as a contract made by consent. Carrying out the standard obligations of the marriage bargain—cohabitation, husband's support, wife's service—seems to have been much more central to the approbation of local communities at this time than how or when the marriage took place, and whether one of the partners had been married elsewhere before. [5]

It also should be remembered that because Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Latter-day Saint leaders exercised exclusive jurisdiction over celestial or plural marriages, marriages conducted under their supervision had as much (or more) formal oversight as many traditional marriages in America during the first half of the nineteenth century. Critics of the Church offer us none of this information or perspective—with the result that some readers might be horrified by the "loose" marriage practices of the Saints.

Some critics of Mormonism like to emphasize that some LDS members did not receive civil divorces before remarrying—either monogamously or polygamously. They either state or imply that this shows the Saints' cavalier attitude toward the law.

The Saints were often poor and spent most of their time on the frontier, where the legal apparatus of the state was particularly feeble. Women who had joined the church and traveled to Zion without their husbands were particularly likely to be poor, and also unlikely to be worried about property rights. Critics usually tell us nothing of all this—with the result that some credulous readers might be horrified by the "loose" marriage practices of the Saints. It also should be remembered that because Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Latter-day Saint leaders exercised exclusive jurisdiction over celestial or plural marriages, marriages conducted under their supervision had as much (or more) formal oversight as many traditional marriages in America during the first half of the nineteenth century.

"From the standpoint of the legal historian," wrote one expert who is not a Latter-day Saint, "it is perhaps surprising that anyone prosecuted bigamy at all. Given the confusion over conflicting state laws on marriage, there were many ways to escape notice, if not conviction." [6]

Bigamy or, rather, serial monogamy (without divorce or death) was a common social experience in early America. Much of the time, serial monogamists were poor and transient people, for whom the property rights that came with a recognized marriage would not have been much of a concern, people whose lives only rarely intersected with the law of marriage. [7]

Nor, not incidentally, were their husbands available for a formal divorce.

Does this mean that marriage in America was a free-for-all? Hardly, notes Nancy Cott:

When couples married informally, or reversed the order of divorce and remarriage, they were not simply acting privately, taking the law into their own hands. . . . A couple about to join or leave an intimate relationship looked for communal sanction. The surrounding local community provided the public oversight necessary. Without resort to the state apparatus, local informal policing by the community affirmed that marriage was a well-defined public institution as well as a contract made by consent. Carrying out the standard obligations of the marriage bargain—cohabitation, husband’s support, wife’s service—seems to have been much more central to the approbation of local communities at this time than how or when the marriage took place, and whether one of the partners had been married elsewhere before. [8]

Critical sources |

|

Did Joseph propose a "tryst" with his plural wife Sarah Ann Whitney?

Author's sources:

- Joseph Smith to "Brother and Sister, [Newel K.] Whitney, and &c. [Sarah Ann,] Nauvoo, Illinois, August 18, 1842, Joseph Smith Collections, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), Salt Lake City, Utah

- Full text of the letter may be viewed at Letter from Joseph Smith to the Whitneys (18 August 1842) (Wikisource)

Whitney "love letter" (edit)

Gregory L. Smith, A review of Nauvoo Polygamy:...but we called it celestial marriage by George D. Smith. FARMS Review, Vol. 20, Issue 2. (Detailed book review)

Critics of the Church would have us believe that this is a private, secret "love letter" from Joseph to Sarah Ann, however, Joseph wrote this letter to the Whitney's, addressing it to Sarah's parents. The "matter" to which he refers is likely the administration of ordinances rather than the arrangement of some sort of private tryst with one of his plural wives. Why would one invite your bride's parents to such an encounter? Joseph doesn't want Emma gone because he wants to be alone with Sarah Ann—a feat that would be difficult to accomplish with her parents there—he wants Emma gone either because she is opposed to plural marriage (the contention that would result from an encounter between Emma and the Whitney's just a few weeks after Joseph's sealing to Sarah Ann would hardly be conducive to having the spirit present in order to "git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads"), or because she may have been followed or spied upon by Joseph's enemies, putting either Joseph or the Whitneys in danger.

On the 16th of August, 1842, while Joseph was in hiding at the Sayer's, Emma expressed concern for Joseph's safety. She sent a letter to Joseph in which she noted,

There are more ways than one to take care of you, and I believe that you can still direct in your business concerns if we are all of us prudent in the matter. If it was pleasant weather I should contrive to see you this evening, but I dare not run too much of a risk, on account of so many going to see you. (History of the Church, Vol.5, Ch.6, p.109)

Joseph wrote the next day in his journal,

Several rumors were afloat in the city, intimating that my retreat had been discovered, and that it was no longer safe for me to remain at Brother Sayers'; consequently Emma came to see me at night, and informed me of the report. It was considered wisdom that I should remove immediately, and accordingly I departed in company with Emma and Brother Derby, and went to Carlos Granger's, who lived in the north-east part of the city. Here we were kindly received and well treated." (History of the Church, Vol.5, Ch.6, pp. 117-118)

The letter is addressed to "Brother and Sister Whitney, and &c." Scholars agree that the third person referred to was the Whitney's daughter Sarah Ann, to whom Joseph had been sealed in a plural marriage, without Emma's knowledge, three weeks prior. The full letter, with photographs of the original document, was published by Michael Marquardt in 1973,[1] and again in 1984 by Dean C. Jessee in The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith.[2] The complete text of the letter reads as follows (original spelling has been retained):

Nauvoo August 18th 1842

Dear, and Beloved, Brother and Sister, Whitney, and &c.—

I take this oppertunity to communi[c]ate, some of my feelings, privetely at this time, which I want you three Eternaly to keep in your own bosams; for my feelings are so strong for you since what has pased lately between us, that the time of my abscence from you seems so long, and dreary, that it seems, as if I could not live long in this way: and <if you> three would come and see me in this my lonely retreat, it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am alied, do love me; now is the time to afford me succour, in the days of exile, for you know I foretold you of these things. I am now at Carlos Graingers, Just back of Brother Hyrams farm, it is only one mile from town, the nights are very pleasant indeed, all three of you come <can> come and See me in the fore part of the night, let Brother Whitney come a little a head, and nock at the south East corner of the house at <the> window; it is next to the cornfield, I have a room inti=rely by myself, the whole matter can be attended to with most perfect safty, I <know> it is the will of God that you should comfort <me> now in this time of affliction, or not at[ta]l now is the time or never, but I hav[e] no kneed of saying any such thing, to you, for I know the goodness of your hearts, and that you will do the will of the Lord, when it is made known to you; the only thing to be careful of; is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty: only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible, I know it is a heroick undertakeing; but so much the greater frendship, and the more Joy, when I see you I <will> tell you all my plans, I cannot write them on paper, burn this letter as soon as you read it; keep all locked up in your breasts, my life depends upon it. one thing I want to see you for is <to> git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads, &c. you wi will pardon me for my earnest=ness on <this subject> when you consider how lonesome I must be, your good feelings know how to <make> every allowance for me, I close my letter, I think Emma wont come tonight if she dont dont fail to come to night. I subscribe myself your most obedient, <and> affectionate, companion, and friend.

Joseph Smith

Some critics point to this letter as evidence the Joseph wrote a private and secret "love letter" to Sarah Ann, requesting that she visit him while he was in seclusion. Others believe that the letter was a request to Sarah Ann's parents to bring their daughter to him so that he could obtain "comfort," with the implication that "comfort" involved intimate relations.

Did Joseph Smith write a private and secret "love letter" to Sarah Ann Whitney? Was this letter a request to Sarah Ann's parents to bring her to Joseph? Was Joseph trying to keep Sarah Ann and Emma from encountering one another? Certain sentences extracted from the letter might lead one to believe one or all of these things. Critics use this to their advantage by extracting only the portions of the letter which support the conclusions above. We present here four examples of how the text of the letter has been employed by critics in order to support their position that Joseph was asking the Whitney's to bring Sarah Ann over for an intimate encounter. The text of the full letter is then examined again in light of these treatments.

Consider the following excerpt from a website that is critical of the Church. Portions of the Whitney letter are extracted and presented in the following manner:

... the only thing to be careful of; is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty. ... Only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible, I know it is a heroick undertakeing; but so much the greater friendship, and the more Joy, when I see you I will tell you all my plans, I cannot write them on paper, burn this letter as soon as you read it; keep all locked up in your breasts, my life depends upon it. ... I close my letter, I think Emma wont come tonight if she dont, dont fail to come to night, I subscribe myself your most obedient, and affectionate, companion, and friend. Joseph Smith.

—’’Rethinking Mormonism’’, "Did Joseph Smith have sex with his wives?" (Web page)

This certainly has all of the elements of a secret "love letter:" The statement that it would not be safe if Emma were there, the request to "burn this letter as soon as you read it," and the stealthy instructions for approaching the house. The question is, who was this letter addressed to? The critics on their web site clearly want you to believe that this was a private letter to Sarah Ann.

Here is the way that Van Wagoner presents selected excerpts of the same letter. In this case, at least, he acknowledges that the letter was addressed to "the Whitney’s," rather than Sarah, but adds his own opinion that it "detailed [Joseph’s] problems in getting to see Sarah Ann without Emma's knowledge:"

My feelings are so strong for you since what has pased lately between us ... if you three would come and see me in this my lonely retreat, it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am alied, do love me, now is the time to Afford me succor ... the only thing to be careful is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safety.

—Richard S. Van Wagoner, Mormon Polygamy: A History, 48.

This version, presented by George D. Smith, presents excerpts from the letter which makes it sound like Joseph was absolutely lusting for the company of Sarah Ann. Smith even makes Napoleon Bonaparte a Joseph Smith doppelgänger by quoting a letter from the future Emperor to Josephine of their first night together:

"I have awakened full of you. The memory of last night has given my senses no rest. . . . What an effect you have on my heart! I send you thousands of kisses—but don’t kiss me. Your kisses sear my blood" (p. xi). George Smith then claims that a "young man of ambition and vision penned his own letter of affection to a young woman. It was the summer of 1842 when thirty-six-year-old Joseph Smith, hiding from the law down by the Mississippi River in Illinois, confessed:"

Smith then compares the excerpts from Napoleon's letter above to portions of the Whitney letter:

My feelings are so strong for you . . . come and see me in this my lonely retreat . . . now is the time to afford me succour . . . I have a room intirely by myself, the whole matter can be attended to with most perfect saf[e]ty, I know it is the will of God that you should comfort me.

—George D. Smith, "Nauvoo Polygamy: We Called It Celestial Marriage," Free Inquiry [Council for Secular Humanism] 28/3 (April–May 2008): 44–46.

Finally, we have a version which acknowledges the full contents of the letter...but only after presenting it in the manner described above numerous times. The author eventually provides the full text of this letter (150 pages after its comparison with Napoleon). Since there are no extant "love letters" from Joseph Smith to any of his plural wives, the mileage that the author of Nauvoo Polygamy..."but we called it celestial marriage" extracts from the single letter to the Whitney's is simply astounding:

- "[i]t was eleven years after the Smiths roomed with the Whitneys that Joseph expressed a romantic interest in their daughter, as well." (p. 31)

- "recommended his friend, whose seventeen-year-old daughter he had just married, should 'come a little a head, and nock…at the window.'" (p. 53)

- "Emma Hale, Joseph's wife of fifteen years, had left his side just twenty-four hours earlier. Now Joseph declared that he was "lonesome," and he pleaded with Sarah Ann to visit him under cover of darkness. After all, they had been married just three weeks earlier. (p. 53)

- "As will be seen, conjugal visits appear furtive and constantly shadowed by the threat of disclosure." (p. 63)

- "when Joseph requested that Sarah Ann Whitney visit him and ‘nock at the window,’ he reassured his new young wife that Emma would not be there, telegraphing his fear of discovery if Emma happened upon his trysts." (p. 65)

- "Three weeks after the wedding, Joseph took steps to spend some time with his newest bride." (p. 138)

- "It was the ninth night of Joseph's concealment, and Emma had visited him three times, written him several letters, and penned at least one letter on his behalf…For his part, Joseph's private note about his love for Emma was so endearing it found its way into the official church history. In it, he vowed to be hers 'forevermore.' Yet within this context of reassurance and intimacy, a few hours later the same day, even while Joseph was still in grave danger and when secrecy was of the utmost urgency, he made complicated arrangements for a visit from his fifteenth plural wife, Sarah Ann Whitney." (p. 142)

- "Smith urged his seventeen-year-old bride to 'come to night' and 'comfort' him—but only if Emma had not returned….Joseph judiciously addressed the letter to 'Brother, and Sister, Whitney, and &c." (p. 142-143)

- "Invites Whitneys to visit, Sarah Ann to 'comfort me' if Emma not there. Invitation accepted." (p.. 147)

- "As if Sarah Ann Whitney's liaison were not enough…another marriage took place…." (p. 155)

- "summer 1842 call for an intimate visit from Sarah Ann Whitney…substantiate[s] the intimate relationships he was involved in during those two years." (p. 185)

- "his warning to Sarah Ann to proceed carefully in order to make sure Emma would not find them in their hiding place." (p. 236)

- "Just as Joseph sought comfort from Sarah Ann the day Emma departed from his hideout…." (p. 236)

- "Elizabeth [Whitney] was arranging conjugal visits between her daughter, Sarah Ann, and [Joseph]…." (p. 366)

One must assume that this is the closest thing that the author could find to a love letter, because the "real" love letters from Joseph to his plural wives do not exist. The author had to make do with this one, despite the fact that it did not precisely fit the bill. With judicious pruning, however, it can be made to sound sufficiently salacious to suit the purpose at hand: to "prove" that Joseph lusted after women.

In contrast to the sources above, Compton actually provides the complete text of the letter up front, and concludes that "[t]he Mormon leader is putting the Whitney's in the difficult position of having to learn about Emma's movements, avoid her, then meet secretly with him" and that the "cloak-and-dagger atmosphere in this letter is typical of Nauvoo polygamy." [3]

As always, it is helpful to view the entire set of statements in content. Let's revisit the entire letter, this time with the selections extracted by the critics highlighted:

Nauvoo August 18th 1842

Dear, and Beloved, Brother and Sister, Whitney, and &c.—

I take this oppertunity to communi[c]ate, some of my feelings, privetely at this time, which I want you three Eternaly to keep in your own bosams; for my feelings are so strong for you since what has pased lately between us, that the time of my abscence from you seems so long, and dreary, that it seems, as if I could not live long in this way: and <if you> three would come and see me in this my lonely retreat, it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am alied, do love me; now is the time to afford me succour, in the days of exile, for you know I foretold you of these things. I am now at Carlos Graingers, Just back of Brother Hyrams farm, it is only one mile from town, the nights are very pleasant indeed, all three of you come <can> come and See me in the fore part of the night, let Brother Whitney come a little a head, and nock at the south East corner of the house at <the> window; it is next to the cornfield, I have a room inti=rely by myself, the whole matter can be attended to with most perfect safty, I <know> it is the will of God that you should comfort <me> now in this time of affliction, or not at[ta]l now is the time or never, but I hav[e] no kneed of saying any such thing, to you, for I know the goodness of your hearts, and that you will do the will of the Lord, when it is made known to you; the only thing to be careful of; is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty: only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible, I know it is a heroick undertakeing; but so much the greater frendship, and the more Joy, when I see you I <will> tell you all my plans, I cannot write them on paper, burn this letter as soon as you read it; keep all locked up in your breasts, my life depends upon it. one thing I want to see you for is <to> git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads, &c. you wi will pardon me for my earnest=ness on <this subject> when you consider how lonesome I must be, your good feelings know how to <make> every allowance for me, I close my letter, I think Emma wont come tonight if she dont dont fail to come to night. I subscribe myself your most obedient, <and> affectionate, companion, and friend.

Joseph Smith

So, let’s take a look at the portions of the letter that are not highlighted.

Dear, and Beloved, Brother and Sister, Whitney, and &c.—

The letter is addressed to "Brother and Sister Whitney." Sarah Ann is not mentioned by name, but is included as "&c.," which is the equivalent of saying "and so on," or "etc." This hardly implies that what follows is a private "love letter" to Sarah Ann herself.

Could this have been an appeal to Sarah's parents to bring her to Joseph? In Todd Compton's opinion, Joseph "cautiously avoids writing Sarah's name." [4] However, Joseph stated in the letter who he wanted to talk to:

I take this oppertunity to communi[c]ate, some of my feelings, privetely at this time, which I want you three Eternaly to keep in your own bosams;

Joseph wants to talk to "you three," meaning Newel, Elizabeth and Sarah Ann.

Interestingly enough, the one portion of the letter in which Joseph actually gives a reason for this meeting is often excluded by critics:

..one thing I want to see you for is <to> git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads, &c. you wi will pardon me for my earnest=ness on <this subject> when you consider how lonesome I must be, your good feelings know how to <make> every allowance for me...

According to Richard L. Bushman, this may have been "a reference perhaps to the sealing of Newel and Elizabeth in eternal marriage three days later." [5] Compton adds, "This was not just a meeting of husband and plural wife, it was a meeting with Sarah's family, with a religious aspect.[6]

In addition to the stated purpose of the meeting, Joseph "may have been a lonely man who needed people around him every moment." [7] Consider this phrase (included in Van Wagoner's treatment, but excluded by the others):

...it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am al[l]ied, do love me, now is the time to afford me succour, in the days of exile. (emphasis added)

These are not the words of a man asking his secret lover to meet him for a private tryst—they are the words of a man who wants the company of friends.

So, what about Emma? The letter certainly contains dire warnings about having the Whitney's avoid an encounter with Emma. We examine several possible reasons for the warning about Emma. Keep in mind Emma's stated concern just two days prior,

If it was pleasant weather I should contrive to see you this evening, but I dare not run too much of a risk, on account of so many going to see you. (History of the Church, Vol.5, Ch.6, p.109)

Joseph had been sealed to Sarah Ann three weeks before without Emma's knowledge.[8] Joseph may have wished to offer a sealing blessing to Newel and Elizabeth Whitney at this time. Given Joseph's indication to the Whitneys that he wished to "git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads," and the fact that Emma herself was not sealed until she consented to the doctrine of plural marriage nine months later, Joseph may have felt that Emma’s presence would create an uncomfortable situation for all involved—particularly if she became aware of his sealing to Sarah Ann.

If Joseph was in hiding, he had good reason to avoid being found (hence the request to burn the letter that disclosed his location). He would also not want his friends present in case he were to be found. Anyone that was searching for Joseph knew that Emma could lead them to him if they simply observed and followed her. If this were the case, the most dangerous time for the Whitney's to visit Joseph may have been when Emma was there—not necessarily because Emma would have been angered by finding Sarah Ann (after all, Emma did not know about the sealing, and she would have found all three Whitney's there—not just Sarah Ann), but because hostile men might have found the Whitney's with Joseph. Note that Joseph's letter states that "when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty: only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible." Joseph wanted the Whitneys to avoid observation by anyone, and not just by Emma.

Critical sources |

|

The point is made that Joseph was age 36, versus Sarah Ann Whitney at age 17.

Author's sources:

- No source provided

Ages of wives (edit)

Summary: Helen was nearly fifteen when her father urged her to be sealed to Joseph Smith

Some points regarding the circumstances surrounding the sealing of Helen Mar Kimball to Joseph Smith[2]:

During the winter of 1843, there were plenty of parties and balls. … Some of the young gentlemen got up a series of dancing parties, to be held at the Mansion once a week. … I had to stay home, as my father had been warned by the Prophet to keep his daughter away from there, because of the blacklegs and certain ones of questionable character who attended there. … I felt quite sore over it, and thought it a very unkind act in father to allow [my brother] to go and enjoy the dance unrestrained with others of my companions, and fetter me down, for no girl loved dancing better than I did, and I really felt that it was too much to bear. It made the dull school still more dull, and like a wild bird I longer for the freedom that was denied me; and thought myself a much abused child, and that it was pardonable if I did murmur.[8]

Brian Hales observes:

In 1892, the RLDS Church led by Joseph Smith III sued the Church of Christ (Temple Lot),[9] disputing its claim to own the temple lot in Independence, Missouri. The Church of Christ (Temple Lot) held physical possession, and the RLDS Church took the official position that since it was the true successor of the church originally founded by Joseph Smith, it owned the property outright.[10]

Although the LDS Church was not a party to the suit, it provided support to the Church of Christ (Temple Lot). The issue was parsed this way: If the Church of Christ (Temple Lot) could prove that plural marriage was part of the original Church, then the RLDS Church was obviously not the true successor since it failed to practice such a key doctrine.[11]During the proceedings, three plural wives of Joseph Smith (Lucy Walker, Emily Partridge, and Malissa Lott) were deposed.[12]

Why was Helen Kimball Whitney not also called to testify in the Temple Lot trial regarding her marriage relations with Joseph Smith? She lived in Salt Lake City, geographically much closer than two of the three witnesses: Malissa Lott live thirty miles south in Lehi, and Lucy Walker lived eighty-two miles north in Logan.

A likely reason is that Helen could not provide the needed testimony. All three of Joseph Smith’s wives who did testify affirmed that sexual relations were part of their plural marriages to the Prophet.[13] Testifying of either an unconsummated time-and-eternity sealing or an eternity-only marriage would have hurt the Temple Lot case. Such marriages would have been easily dismissed as unimportant.

If Helen’s plural union did not include conjugality, her testimony would not have been helpful. If it did, the reason for not inviting her to testify is not obvious. Not only was Helen passed over, but Mary Elizabeth Lightner, Zina Huntington, and Patty Sessions, who were sealed to Joseph in eternity-only marriages, were similarly not deposed.

The lack of evidence does not prove the lack of sexual relations, but these observations are consistent with an unconsummated union.

I am thankful that He [Heavenly Father] has brought me through the furnace of affliction and that He has condescended to show me that the promises made to me the morning that I was sealed to the Prophet of God will not fail and I would not have the chain broken for I have had a view of the principle of eternal salvation and the perfect union which this sealing power will bring to the human family and with the help of our Heavenly Father I am determined to so live that I can claim those promises.[14]

Later in life, Helen wrote a poem entitled "Reminiscences." It is often cited for the critics' claims:

The first portion of the poem expresses the youthful Helen's attitude. She is distressed mostly because of the loss of socialization and youthful ideas about romance. But, as Helen was later to explain more clearly in prose, she would soon realize that her youthful pout was uncalled for—she saw that her plural marriage had, in fact, protected her. "I have long since learned to leave all with Him, who knoweth better than ourselves what will make us happy," she noted after the poem.[16]

Thus, she would later write of her youthful disappointment in not being permitted to attend a party or dance:

During the winter of 1843, there were plenty of parties and balls. … Some of the young gentlemen got up a series of dancing parties, to be held at the Mansion once a week. … I had to stay home, as my father had been warned by the Prophet to keep his daughter away from there, because of the blacklegs and certain ones of questionable character who attended there. … I felt quite sore over it, and thought it a very unkind act in father to allow [my brother] to go and enjoy the dance unrestrained with others of my companions, and fetter me down, for no girl loved dancing better than I did, and I really felt that it was too much to bear. It made the dull school still more dull, and like a wild bird I longed for the freedom that was denied me; and thought myself a much abused child, and that it was pardonable if I did murmur.

I imagined that my happiness was all over and brooded over the sad memories of sweet departed joys and all manner of future woes, which (by the by) were of short duration, my bump of hope being too large to admit of my remaining long under the clouds. Besides my father was very kind and indulgent in other ways, and always took me with him when mother could not go, and it was not a very long time before I became satisfied that I was blessed in being under the control of so good and wise a parent who had taken counsel and thus saved me from evils, which some others in their youth and inexperience were exposed to though they thought no evil. Yet the busy tongue of scandal did not spare them. A moral may be drawn from this truthful story. "Children obey thy parents," etc. And also, "Have regard to thy name, for that shall continue with you above a thousand great treasures of gold." "A good life hath but few days; but a good name endureth forever.[17]

So, despite her youthful reaction, Helen uses this as an illustration of how she was being a bit immature and upset, and how she ought to have trusted her parents, and that she was actually protected from problems that arose from the parties she missed.

Critics of the Church provide a supposed "confession" from Helen, in which she reportedly said:

I would never have been sealed to Joseph had I known it was anything more than ceremony. I was young, and they deceived me, by saying the salvation of our whole family depended on it.[18]

Author Todd Compton properly characterizes this source, noting that it is an anti-Mormon work, and calls its extreme language "suspect."[19]

Author George D. Smith tells his readers only that this is Helen "confiding," while doing nothing to reveal the statement's provenance from a hostile source.[20] Newell and Avery tell us nothing of the nature of this source and call it only a "statement" in the Stanley Ivins Collection;[21] Van Wagoner mirrors G. D. Smith by disingenuously writing that "Helen confided [this information] to a close Nauvoo friend," without revealing its anti-Mormon origins.[22]

To credit this story at face value, one must also admit that Helen told others in Nauvoo about the marriage (something she repeatedly emphasized she was not to do) and that she told a story at variance with all the others from her pen during a lifetime of staunch defense of plural marriage.[23]

As Brian Hales writes:

It is clear that Helen’s sealing to Joseph Smith prevented her from socializing as an unmarried lady. The primary document referring to the relationship is an 1881 poem penned by Helen that has been interpreted in different ways ...

After leaving the church, dissenter Catherine Lewis reported Helen saying: "I would never have been sealed to Joseph had I known it was anything more than a ceremony."

Assuming this statement was accurate, which is not certain, the question arises regarding her meaning of "more than a ceremony"? While sexuality is a possibility, a more likely interpretation is that the ceremony prevented her from associating with her friends as an unmarried teenager, causing her dramatic distress after the sealing.[24]

Critics generally do not reveal that their sources have concluded that Helen's marriage to Joseph Smith was unconsummated, preferring instead to point out that mere fact of the marriage of a 14-year-old girl to a 37-year-old man ought to be evidence enough to imply sexual relations and "pedophilia." For example, George D. Smith quotes Compton without disclosing his view,[25] cites Compton, but ignores that Compton argues that " there is absolutely no evidence that there was any sexuality in the marriage, and I suggest that, following later practice in Utah, there may have been no sexuality. All the evidence points to this marriage as a primarily dynastic marriage." [26] and Stanley Kimball without disclosing that he believed the marriage to be "unconsummated." [27]

Critical sources |

|

Helen made clear what she disliked about plural marriage in Nauvoo, and it was not physical relations with an older man:

I had, in hours of temptation, when seeing the trials of my mother, felt to rebel. I hated polygamy in my heart, I had loved my baby more than my God, and mourned for it unreasonably….[28]

Helen is describing a period during the westward migration when (married monogamously) her first child died. Helen was upset by polygamy only because she saw the difficulties it placed on her mother. She is not complaining about her own experience with it.

Helen Mar Kimball:

All my sins and shortcomings were magnified before my eyes till I believed I had sinned beyond redemption. Some may call it the fruits of a diseased brain. There is nothing without a cause, be that as it may, it was a keen reality to me. During that season I lost my speech, forgot the names of everybody and everything, and was living in another sphere, learning lessons that would serve me in future times to keep me in the narrow way. I was left a poor wreck of what I had been, but the Devil with all his cunning, little thought that he was fitting and preparing my heart to fulfill its destiny….

[A]fter spending one of the happiest days of my life I was moved upon to talk to my mother. I knew her heart was weighed down in sorrow and I was full of the holy Ghost. I talked as I never did before, I was too weak to talk with such a voice (of my own strength), beside, I never before spoke with such eloquence, and she knew that it was not myself. She was so affected that she sobbed till I ceased. I assured her that father loved her, but he had a work to do, she must rise above her feelings and seek for the Holy Comforter, and though it rent her heart she must uphold him, for he in taking other wives had done it only in obedience to a holy principle. Much more I said, and when I ceased, she wiped her eyes and told me to rest. I had not felt tired till she said this, but commenced then to feel myself sinking away. I silently prayed to be renewed, when my strength returned that instant…

I have encouraged and sustained my husband in the celestial order of marriage because I knew it was right. At various times I have been healed by the washing and annointing, administered by the mothers in Israel. I am still spared to testify to the truth and Godliness of this work; and though my happiness once consisted in laboring for those I love, the Lord has seen fit to deprive me of bodily strength, and taught me to 'cast my bread upon the waters' and after many days my longing spirit was cheered with the knowledge that He had a work for me to do, and with Him, I know that all things are possible…[29]

Imagine a school-child who asks why French knights didn't resist the English during the Battle of Agincourt (in 1415) using Sherman battle tanks. We might gently reply that there were no such tanks available. The child, a precocious sort, retorts that the French generals must have been incompetent, because everyone knows that tanks are necessary. The child has fallen into the trap of presentism—he has presumed that situations and circumstances in the past are always the same as the present. Clearly, there were no Sherman tanks available in 1415; we cannot in fairness criticize the French for not using something which was unavailable and unimagined.

Spotting such anachronistic examples of presentism is relatively simple. The more difficult problems involve issues of culture, behavior, and attitude. For example, it seems perfectly obvious to most twenty-first century North Americans that discrimination on the basis of race is wrong. We might judge a modern, racist politician quite harshly. We risk presentism, however, if we presume that all past politicians and citizens should have recognized racism, and fought it. In fact, for the vast majority of history, racism has almost always been present. Virtually all historical figures are, by modern standards, racists. To identify George Washington or Thomas Jefferson as racists, and to judge them as moral failures, is to be guilty of presentism.

A caution against presentism is not to claim that no moral judgments are possible about historical events, or that it does not matter whether we are racists or not. Washington and Jefferson were born into a culture where society, law, and practice had institutionalized racism. For them even to perceive racism as a problem would have required that they lift themselves out of their historical time and place. Like fish surrounded by water, racism was so prevalent and pervasive that to even imagine a world without it would have been extraordinarily difficult. We will not properly understand Washington and Jefferson, and their choices, if we simply condemn them for violating modern standards of which no one in their era was aware.

Condemning Joseph Smith for "statutory rape" is a textbook example of presentist history. "Rape," of course, is a crime in which the victim is forced into sexual behavior against her (or his) will. Such behavior has been widely condemned in ancient and modern societies. Like murder or theft, it arguably violates the moral conscience of any normal individual. It was certainly a crime in Joseph Smith's day, and if Joseph was guilty of forced sexual intercourse, it would be appropriate to condemn him.

(Despite what some claim, not all marriages or sealings were consummated, as in Helen's case discussed above.)

"Statutory rape," however, is a completely different matter. Statutory rape is sexual intercourse with a victim that is deemed too young to provide legal consent--it is rape under the "statute," or criminal laws of the nation. Thus, a twenty-year-old woman who chooses to have sex has not been raped. Our society has concluded, however, that a ten-year-old child does not have the physical, sexual, or emotional maturity to truly understand the decision to become sexually active. Even if a ten-year-old agrees to sexual intercourse with a twenty-year-old male, the male is guilty of "statutory rape." The child's consent does not excuse the adult's behavior, because the adult should have known that sex with a minor child is illegal.

Even in the modern United States, statutory rape laws vary by state. A twenty-year-old who has consensual sex with a sixteen-year-old in Alabama would have nothing to fear; moving to California would make him guilty of statutory rape even if his partner was seventeen.

By analogy, Joseph Smith likely owned a firearm for which he did not have a license--this is hardly surprising, since no law required guns to be registered on the frontier in 1840. It would be ridiculous for Hitchens to complain that Joseph "carried an unregistered firearm." While it is certainly true that Joseph's gun was unregistered, this tells us very little about whether Joseph was a good or bad man. The key question, then, is not "Would Joseph Smith's actions be illegal today?" Only a bigot would condemn someone for violating a law that had not been made.

Rather, the question should be, "Did Joseph violate the laws of the society in which he lived?" If Joseph did not break the law, then we might go on to ask, "Did his behavior, despite not being illegal, violate the common norms of conscience or humanity?" For example, even if murder was not illegal in Illinois, if Joseph repeatedly murdered, we might well question his morality.

"Pedophilia" applies to children; Helen was regarded as a mature young woman

Helen specifically mentioned that she was regarded as mature.[30] 'Pedophilia' is an inflammatory charge that refers to a sexual attraction to pre-pubertal children. It simply does not apply in the present case, even if the relationship had been consummated.

Critics of Mormonism claim that Helen Mar Kimball was prepubescent at the time that she was sealed to Joseph Smith, and that this is therefore evidence that Joseph was a pedophile. Pedophila describes a sexual attraction to prepubescent children. However, there is no evidence that Helen ever cohabited with or had sexual relations with Joseph. In fact, she continued to live with her parents after the sealing.

The use of the term "pedophilia" by critics in this situation is intended to generate a negative emotional response in the reader. Pedophiles don't advertise their obsession and they certainly don't discuss marriages with the parents of their intended victims. It was Heber C. Kimball that requested that this sealing be performed, not Joseph. There is no evidence that Joseph was a pedophile.

European data indicates a long term linear drop, while US data is much more sparse. Using post-1910 data, Wyshak (1983) determined that the average age at menarche was dropping linearly at 3.2 month/decade with a value of 13.1 in 1920. This trend projects to 15.2 in 1840 and 16.3 in 1800. The onset of menarche follows a normal distribution that had a larger spread in the 19th century (σ≈1.7 to 2.0) in Brown (1966) and Laslett (1977).[31]

Helen Mar Kimball was likely married near the end of the month of May in 1843 and was thus approximately 14.8 years old when she was sealed to Joseph Smith. With only the statistics cited above we can conclude that 40% of the young women her age would have already matured and thus in their society be considered marriage eligible. If 40% is taken as an a priori probability, additional information puts maturity at her first marriage beyond a reasonable doubt using Bayesian methodology.

Helen remembered transitioning from childhood to adulthood over a year before her first marriage as she attended social functions with older teens. Here is quote on the abruptness of this transition in the past from a graduate course's textbook on child development:

In industrial societies, as we have mentioned, the concept of adolescence as a period of development is quite recent. Until the early twentieth century, young people were considered children until they left school (often well before age 13), married or got a job, and entered the adult world. By the 1920s, with the establishment of comprehensive high schools to meet the needs of a growing economy and with more families able to support extended formal education for their children, the teenage years had become a distinct period of development (Keller, 1999). In some preindustrial societies, the concept of adolescence still does not exist. The Chippewa, for example, have only two periods of childhood: from birth until the child walks, and from walking to puberty. What we call adolescence is, for them, part of adulthood (Broude, 1995), as was true in societies before industrialization.[32]

Helen recalls that by March 1842, she "had grown up very fast and my father often took me out with him and for this reason was taken to be older than I was." At these social gatherings, she developed a crush on her future husband Horace Whitney. She later married him after Joseph Smith's martyrdom and her 16th birthday and had 12 children with him.

According to Helen:

Sarah Ann's brother, Horace, who was twenty months her senior, made one of the party but had never dreamed of such a thing as matrimony with me, whom he only remembered in the earliest school days in Kirtland as occupying one of the lowest seats. He becoming enough advanced, soon left the one taught in the red schoolhouse on the flat and attended a higher one on the hill, and through our moving to Missouri and Illinois we lost sight of each other. After the party was over I stopped the rest of the night with Sarah, and as her room and his were adjoining, being only separated by a partition, our talk seemed to disturb him, and he was impolite enough to tell us of it, and request us to stop and let him go to sleep, which was proof enough that he had never thought of me only as the green school girl that I was, or he would certainly have submitted gracefully (as lovers always should) to be made a martyr of.[33]

Scholars that study fertility often divide large samples into cohorts which are 5 years wide based on birth year or marriage age . In contrast to what some critics claim, the marriage cohort of 15-19 year olds has been shown at times to be more fertile than the 20-24 cohort. The authors of one study found that "Unlike most other reported natural-fertility populations, period fertility rates for married Mormon women aged 15-19 are higher between 1870 and 1894 than those for married women in their 20s. Women aged 15-19 in 1870-74 would have been born in the 1850s when 55.8 percent were married before their 20th birthday; thus, this cannot be treated as an insignificant group." And also "In addition, the median interval between marriage and birth of the first child is consistently about one year for all age-at-marriage groups."[34] Another study disproved that younger marital age (15-19) resulted in a higher infant mortality rate due to the mother not being fully mature (termed the "biological-insufficiency hypothesis.").[35]

Helen continued to live with her parents after the sealing. After Joseph's death, Helen was married and had children.

Unlike today, it was acceptable to be sealed to one person for eternity while being married for time to another person. It is not known if this was the case with Helen, however.

We must, then, address four questions:

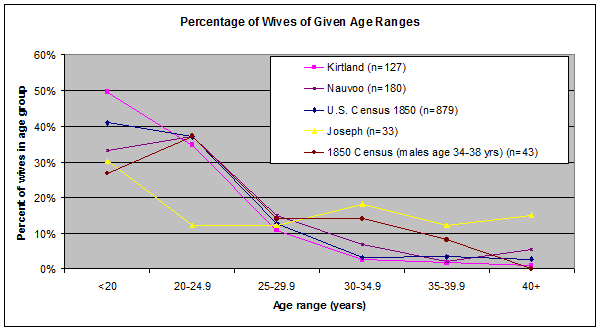

Even LDS authors are not immune from presentist fallacies: Todd Compton, convinced that plural marriage was a tragic mistake, "strongly disapprove[s] of polygamous marriages involving teenage women." [36] This would include, presumably, those marriages which Joseph insisted were commanded by God. Compton notes, with some disapproval, that a third of Joseph's wives were under twenty years of age. The modern reader may be shocked. We must beware, however, of presentism—is it that unusual that a third of Joseph's wives would have been teenagers?

When we study others in Joseph's environment, we find that it was not. A sample of 201 Nauvoo-era civil marriages found that 33.3% were under twenty, with one bride as young as twelve. [37] Another sample of 127 Kirtland marriages found that nearly half (49.6%) were under twenty. [38] And, a computer-aided study of LDS marriages found that from 1835–1845, 42.3% of women were married before age twenty. [39] The only surprising thing about Joseph's one third is that more of his marriage partners were not younger.

Furthermore, this pattern does not seem to be confined to the Mormons (see Chart 12 1). A 1% sample from the 1850 U.S. census found 989 men and 962 who had been married in the last year. Teens made up 36.0% of married women, and only 2.3% of men; the average age of marriage was 22.5 for women and 27.8 for men. [40] Even when the men in Joseph's age range (34–38 years) in the U.S. Census are extracted, Joseph still has a lower percentage of younger wives and more older wives than non-members half a decade later. [41]

I suspect that Compton goes out of his way to inflate the number of young wives, since he lumps everyone between "14 to 20 years old" together. [42] It is not clear why this age range should be chosen—women eighteen or older are adults even by modern standards.

A more useful breakdown by age is found in Table 12-1. Rather than lumping all wives younger than twenty-one together (a third of all the wives), our analysis shows that only a fifth of the wives would be under eighteen. These are the only women at risk of statutory rape issues even in the modern era.

| Age range | Percent (n=33) |

|---|---|

| 14-17 | 21.2% |

| 18-19 | 9.1% |

| 20-29 | 27.3% |

| 30-39 | 27.3% |

| 40-49 | 3.0% |

| 50-59 | 12.1% |

As shown elsewhere, the data for sexual relations in Joseph's plural marriages are quite scant (see Chapter 10—not online). For the purposes of evaluating "statutory rape" charges, only a few relationships are relevant.

The most prominent is, of course, Helen Mar Kimball, who was the prophet's youngest wife, married three months prior to her 15th birthday. [44] As we have seen, Todd Compton's treatment is somewhat confused, but he clarifies his stance and writes that "[a]ll the evidence points to this marriage as a primarily dynastic marriage." [45] Other historians have also concluded that Helen's marriage to Joseph was unconsummated. [46]

Nancy M. Winchester was married at age fourteen or fifteen, but we know nothing else of her relationship with Joseph. [47]

Flora Ann Woodruff was also sixteen at her marriage, and "[a]n important motivation" seems to have been "the creation of a bond between" Flora's family and Joseph. [48] We know nothing of the presence or absence of marital intimacy.

Fanny Alger would have been sixteen if Compton's date for the marriage is accepted. Given that I favor a later date for her marriage, this would make her eighteen. In either case, we have already seen how little reliable information is available for this marriage (see Chapter 4—not online), though on balance it was probably consummated.

Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Sarah Lawrence were each seventeen at the time of their marriage. Here at last we have reliable evidence of intimacy, since Lucy Walker suggested that the Lawrence sisters had consummated their marriage with Joseph. Intimacy in Joseph's marriages may have been more rare than many have assumed—Walker's testimony suggested marital relations with the Partridge and Lawrence sisters, but said nothing about intimacy in her own marriage (see Chapter 10—not online).

Sarah Ann Whitney's marriage had heavy dynastic overtones, binding Joseph to faithful Bishop Orson F. Whitney. We know nothing of a sexual dimension, though Compton presumes that one is implied by references to the couple's "posterity" and "rights" of marriage in the sealing ceremony. [49] This is certainly plausible, though the doctrine of adoption and Joseph's possible desire to establish a pattern for all marriages/sealings might caution us against assuming too much.

Of Joseph's seven under-eighteen wives, then, only one (Lawrence) has even second-hand evidence of intimacy. Fanny Alger has third-hand hostile accounts of intimacy, and we know nothing about most of the others. Lucy Walker and Helen Mar Kimball seem unlikely candidates for consummation.

The evidence simply does not support Christopher Hitchens' wild claim, since there is scant evidence for sexuality in the majority of Joseph's marriages. Many presume that Joseph practiced polygamy to satisfy sexual longings, and with a leer suggest that of course Joseph would have consummated these relationships, since that was the whole point. Such reasoning is circular, and condemns Joseph's motives and actions before the evidence is heard.

Even were we to conclude that Joseph consummated each of his marriages—a claim nowhere sustained by the evidence—this would not prove that he acted improperly, or was guilty of "statutory rape." This requires an examination into the legal climate of his era.

The very concept of a fifteen- or seventeen-year-old suffering statutory rape in the 1840s is flagrant presentism. The age of consent under English common law was ten. American law did not raise the age of consent until the late nineteenth century, and in Joseph Smith's day only a few states had raised it to twelve. Delaware, meanwhile, lowered the age of consent to seven. [50]

In our time, legal minors can often be married before the age of consent with parental approval. Joseph certainly sought and received the approval of parents or male guardians for his marriages to Fanny Alger, Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Helen Kimball. [51] His habit of approaching male relatives on this issue might suggest that permission was gained for other marriages about which we know less.

Clearly, then, Hitchens' attack is hopelessly presentist. None of Joseph's brides was near ten or twelve. And even if his wives' ages had presented legal risks, he often had parental sanction for the match.

There can be no doubt that the practice of polygamy was deeply offensive to monogamous, Victorian America. As everything from the Nauvoo Expositor to the latest anti-Mormon tract shows, the Saints were continually attacked for their plural marriages.

If we set aside the issue of plurality, however, the only issue which remains is whether it would have been considered bizarre, improper, or scandalous for a man in his mid-thirties to marry a woman in her mid- to late-teens. Clearly, Joseph's marriage to teen-age women was entirely normal for Mormons of his era. The sole remaining question is, were all these teen-age women marrying men their own age, or was marriage to older husbands also considered proper?

To my knowledge, the issue of age disparity was not a charge raised by critics in Joseph's day. It is difficult to prove a negative, but the absence of much comment on this point is probably best explained by the fact that plural marriage was scandalous, but marriages with teenage women were, if not the norm, at least not uncommon enough to occasion comment. For example, to disguise the practice of plural marriage, Joseph had eighteen-year-old Sarah Whitney pretend to marry Joseph Kingsbury, who was days away from thirty-one. [52] If this age gap would have occasioned comment, Joseph Smith would not have used Kingsbury as a decoy.

One hundred and eighty Nauvoo-era civil marriages have husbands and wives with known ages and marriage dates. [53] Chart 12 2 demonstrates that these marriages follow the general pattern of wives being younger than husbands.

When the age of husband is plotted against the age of each wife, it becomes clear that almost all brides younger than twenty married men between five and twenty years older (see Chart 12-3).

This same pattern appears in 879 marriages from the 1850 U.S. Census (see Chart 12 4). Non-Mormon age differences easily exceeded Joseph's except for age fourteen. We should not make too much of this, since the sample size is very small (one or two cases for Joseph; three for the census) and dynastic motives likely played a large role in Joseph's choice, as discussed above.

In short, Mormon civil marriage patterns likely mimicked those of their gentile neighbors. Neither Mormons or their critics would have found broad age differences to be an impediment to conjugal marriage. In fact, the age difference between wives and their husbands was greatest in the teen years, and decreased steadily until around Joseph's age, between 30–40 years, when the spread between spouses' ages was narrowest (note the bright pink bars in Chart 12-5).

As Thomas Hine, a non-LDS scholar of adolescence noted:

Why did pre-modern peoples see nothing wrong with teen marriages? Part of the explanation likely lies in the fact that life-expectancy was greatly reduced compared to our time (see Table 12 2).

| Group | Life Expect in 1850 (years) [55] | Life Expect in 1901 (years) [56] | Life Expect in 2004 (years) [57] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males at birth | 38.3 | 47.9 | 75.7 |

| Males at age 20 | 60.1 | 62.0 | 76.6 |

| Females at birth | 40.5 | 50.7 | 80.8 |

| Females at age 20 | 60.2 | 63.6 | 81.5 |

The modern era has also seen the "extension" of childhood, as many more years are spent in schooling and preparation for adult work. In the 1840s, these issues simply weren't in play for women—men needed to be able to provide for their future family, and often had the duties of apprenticeship which prevented early marriage. Virtually everything a woman needed to know about housekeeping and childrearing, however, was taught in the home. It is not surprising, then, that parents in the 1840s considered their teens capable of functioning as married adults, while parents in 2007 know that marriages for young teens will usually founder on issues of immaturity, under-employment, and lack of education.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

Online |

|

Navigators |

The book presents Joseph's letter to Sarah Whitney's parents as analogous to Napoleon's passionate love letter to Josephine.

- Gregory L. Smith, A review of Nauvoo Polygamy:...but we called it celestial marriage by George D. Smith. FARMS Review, Vol. 20, Issue 2. (Detailed book review)

Author's sources:

- Author's opinion.

Whitney "love letter" (edit)

Womanizing & romance (edit)

Critics of the Church would have us believe that this is a private, secret "love letter" from Joseph to Sarah Ann, however, Joseph wrote this letter to the Whitney's, addressing it to Sarah's parents. The "matter" to which he refers is likely the administration of ordinances rather than the arrangement of some sort of private tryst with one of his plural wives. Why would one invite your bride's parents to such an encounter? Joseph doesn't want Emma gone because he wants to be alone with Sarah Ann—a feat that would be difficult to accomplish with her parents there—he wants Emma gone either because she is opposed to plural marriage (the contention that would result from an encounter between Emma and the Whitney's just a few weeks after Joseph's sealing to Sarah Ann would hardly be conducive to having the spirit present in order to "git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads"), or because she may have been followed or spied upon by Joseph's enemies, putting either Joseph or the Whitneys in danger.

On the 16th of August, 1842, while Joseph was in hiding at the Sayer's, Emma expressed concern for Joseph's safety. She sent a letter to Joseph in which she noted,

There are more ways than one to take care of you, and I believe that you can still direct in your business concerns if we are all of us prudent in the matter. If it was pleasant weather I should contrive to see you this evening, but I dare not run too much of a risk, on account of so many going to see you. (History of the Church, Vol.5, Ch.6, p.109)

Joseph wrote the next day in his journal,

Several rumors were afloat in the city, intimating that my retreat had been discovered, and that it was no longer safe for me to remain at Brother Sayers'; consequently Emma came to see me at night, and informed me of the report. It was considered wisdom that I should remove immediately, and accordingly I departed in company with Emma and Brother Derby, and went to Carlos Granger's, who lived in the north-east part of the city. Here we were kindly received and well treated." (History of the Church, Vol.5, Ch.6, pp. 117-118)

The letter is addressed to "Brother and Sister Whitney, and &c." Scholars agree that the third person referred to was the Whitney's daughter Sarah Ann, to whom Joseph had been sealed in a plural marriage, without Emma's knowledge, three weeks prior. The full letter, with photographs of the original document, was published by Michael Marquardt in 1973,[1] and again in 1984 by Dean C. Jessee in The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith.[2] The complete text of the letter reads as follows (original spelling has been retained):

Nauvoo August 18th 1842

Dear, and Beloved, Brother and Sister, Whitney, and &c.—

I take this oppertunity to communi[c]ate, some of my feelings, privetely at this time, which I want you three Eternaly to keep in your own bosams; for my feelings are so strong for you since what has pased lately between us, that the time of my abscence from you seems so long, and dreary, that it seems, as if I could not live long in this way: and <if you> three would come and see me in this my lonely retreat, it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am alied, do love me; now is the time to afford me succour, in the days of exile, for you know I foretold you of these things. I am now at Carlos Graingers, Just back of Brother Hyrams farm, it is only one mile from town, the nights are very pleasant indeed, all three of you come <can> come and See me in the fore part of the night, let Brother Whitney come a little a head, and nock at the south East corner of the house at <the> window; it is next to the cornfield, I have a room inti=rely by myself, the whole matter can be attended to with most perfect safty, I <know> it is the will of God that you should comfort <me> now in this time of affliction, or not at[ta]l now is the time or never, but I hav[e] no kneed of saying any such thing, to you, for I know the goodness of your hearts, and that you will do the will of the Lord, when it is made known to you; the only thing to be careful of; is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty: only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible, I know it is a heroick undertakeing; but so much the greater frendship, and the more Joy, when I see you I <will> tell you all my plans, I cannot write them on paper, burn this letter as soon as you read it; keep all locked up in your breasts, my life depends upon it. one thing I want to see you for is <to> git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads, &c. you wi will pardon me for my earnest=ness on <this subject> when you consider how lonesome I must be, your good feelings know how to <make> every allowance for me, I close my letter, I think Emma wont come tonight if she dont dont fail to come to night. I subscribe myself your most obedient, <and> affectionate, companion, and friend.

Joseph Smith

Some critics point to this letter as evidence the Joseph wrote a private and secret "love letter" to Sarah Ann, requesting that she visit him while he was in seclusion. Others believe that the letter was a request to Sarah Ann's parents to bring their daughter to him so that he could obtain "comfort," with the implication that "comfort" involved intimate relations.

Did Joseph Smith write a private and secret "love letter" to Sarah Ann Whitney? Was this letter a request to Sarah Ann's parents to bring her to Joseph? Was Joseph trying to keep Sarah Ann and Emma from encountering one another? Certain sentences extracted from the letter might lead one to believe one or all of these things. Critics use this to their advantage by extracting only the portions of the letter which support the conclusions above. We present here four examples of how the text of the letter has been employed by critics in order to support their position that Joseph was asking the Whitney's to bring Sarah Ann over for an intimate encounter. The text of the full letter is then examined again in light of these treatments.

Consider the following excerpt from a website that is critical of the Church. Portions of the Whitney letter are extracted and presented in the following manner:

... the only thing to be careful of; is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safty. ... Only be careful to escape observation, as much as possible, I know it is a heroick undertakeing; but so much the greater friendship, and the more Joy, when I see you I will tell you all my plans, I cannot write them on paper, burn this letter as soon as you read it; keep all locked up in your breasts, my life depends upon it. ... I close my letter, I think Emma wont come tonight if she dont, dont fail to come to night, I subscribe myself your most obedient, and affectionate, companion, and friend. Joseph Smith.

—’’Rethinking Mormonism’’, "Did Joseph Smith have sex with his wives?" (Web page)

This certainly has all of the elements of a secret "love letter:" The statement that it would not be safe if Emma were there, the request to "burn this letter as soon as you read it," and the stealthy instructions for approaching the house. The question is, who was this letter addressed to? The critics on their web site clearly want you to believe that this was a private letter to Sarah Ann.

Here is the way that Van Wagoner presents selected excerpts of the same letter. In this case, at least, he acknowledges that the letter was addressed to "the Whitney’s," rather than Sarah, but adds his own opinion that it "detailed [Joseph’s] problems in getting to see Sarah Ann without Emma's knowledge:"

My feelings are so strong for you since what has pased lately between us ... if you three would come and see me in this my lonely retreat, it would afford me great relief, of mind, if those with whom I am alied, do love me, now is the time to Afford me succor ... the only thing to be careful is to find out when Emma comes then you cannot be safe, but when she is not here, there is the most perfect safety.

—Richard S. Van Wagoner, Mormon Polygamy: A History, 48.