FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|L9=Peterson: "the identification of a crocodile as the idolatrous god of Pharaoh...Unas’ pyramid texts, includes the following: 'The king appears as the crocodile god Sobek'" | |L9=Peterson: "the identification of a crocodile as the idolatrous god of Pharaoh...Unas’ pyramid texts, includes the following: 'The king appears as the crocodile god Sobek'" | ||

|L10=Question: Does Facsimile 1 show a hand, or does it show the wing of a second bird? | |L10=Question: Does Facsimile 1 show a hand, or does it show the wing of a second bird? | ||

|L11=Question: Do the names "Elkenah," "Libnah," "Mahmackrah," and "Korash" in Facsimile 1 have any correlation to known ancient deities? | |||

}} | }} | ||

</onlyinclude> | </onlyinclude> | ||

Summary: It is claimed that facsimile 1 is simply a typical funerary scene and there are many other papyri showing the same basic scene, and that the missing portions of the drawing were incorrectly restored. It is also claimed that Abraham has never been associated with the lion couch vignette such as that portrayed in Facsimile #1 of the Book of Abraham.

Jump to details:

The following claims are made regarding Facsimile 1:

Gospel Topics on LDS.org:

Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles of the book of Abraham contain additional earmarks of the ancient world. Facsimile 1 and Abraham 1꞉17 mention the idolatrous god Elkenah. This deity is not mentioned in the Bible, yet modern scholars have identified it as being among the gods worshipped by ancient Mesopotamians. Joseph Smith represented the four figures in figure 6 of facsimile 2 as “this earth in its four quarters.” A similar interpretation has been argued by scholars who study identical figures in other ancient Egyptian texts. Facsimile 1 contains a crocodile deity swimming in what Joseph Smith called “the firmament over our heads.” This interpretation makes sense in light of scholarship that identifies Egyptian conceptions of heaven with “a heavenly ocean.” [1]

The papyrus with the illustration represented in Facsimile 1 (view) is the only recovered item that has any connection to the text of the Book of Abraham.

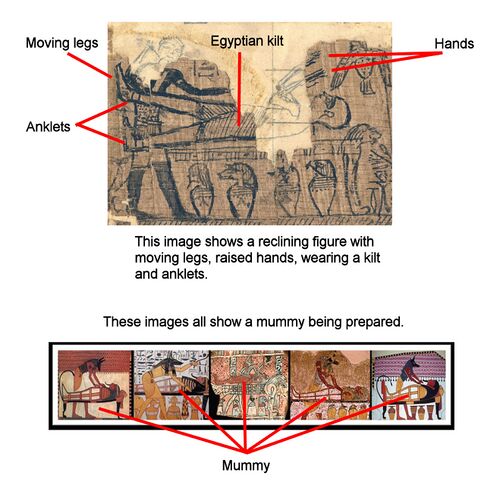

This vignette is called a "lion couch scene" by Egyptologists. It usually represents the embalming of the deceased individual in preparation for burial. However, this particular lion couch scene represents the resurrection of Hor (figure 2), aided by the Egyptian god Anubis (3).[2]

Abraham 1꞉12 and the notes to Facsimile 1 identify it as representing Abraham being sacrificed by the priest of Elkenah in Ur.

Although many similar lion couch scenes exist, this one has quite a few unique features:

Therefore, we do not agree that it is the "same funeral scene." Facsimile 1 actually depicts the resurrection of Osiris. The figure on the couch is alive. The figures to which it is compared all show the preparation of a mummy.

Abraham noted that the attempt to sacrifice him "was done after the manner of the Egyptians" (Abraham 1:11). Egyptologists Kerry Muhlestein and John Gee note that evidence has been uncovered of the practice of human sacrifice in ancient Egypt,

[A]rchaeologists have discovered evidence of human sacrifice. Just outside the Middle Kingdom fortress at Mirgissa, which had been part of the Egyptian empire in Nubia, a deposit was found containing various ritual objects such as melted wax figurines, a flint knife, and the decapitated body of a foreigner slain during rites designed to ward off enemies. Almost universally, this discovery has been accepted as a case of human sacrifice.20 Texts from this and similar rites from the Middle Kingdom specify that the ritual was directed against "every evil speaker, every evil speech, every evil curse, every evil plot, every evil imprecation, every evil attack, every evil rebellion, every evil plan, and every evil thing,"[3] which refers to those who "speak evil" of the king or of his policies.[4] The remains in the deposit are consistent with those of later ritual texts describing the daily execration rite, which was usually a wax figure substituting in effigy for a human sacrifice: "Bind with the sinew of a red cow . . . spit on him four times . . . trample on him with the left foot . . . smite him with a spear . . . decapitate him with a knife . . . place him on the fire . . . spit on him in the fire many times."[5] Again we see that the use of a knife was followed by burning. The fact that the site of Mirgissa is not in Egypt proper but was part of the Egyptian empire in Nubia informs us that the Egyptians extended such practices beyond their borders.

In fact, throughout time we find that ritual violence was often aimed at foreign places and people.[6] Their very foreignness was seen as a threat to Egypt's political and social order. Hence many of the known examples of ritual slaying are aimed at foreigners, such as those at Mirgissa or Tod. All three examples we have shared involve protecting sacred places and things, such as the boundary of a necropolis, a temple, or even Egypt itself.[7]

The Apocalypse of Abraham is a Jewish document composed between about 70–150 AD. The Apocalypse of Abraham describes the idolatry of Abraham's father in detail, and talks of how Abraham came to disbelieve in his father's gods:

VIII. And it came to pass while I spake thus to my father Terah in the court of my house, there cometh down the voice of a Mighty One from heaven in a fiery cloud-burst, saying and crying: “Abraham, Abraham!” And I said: “Here am I.” And He said: “Thou art seeking in the understanding of thine heart the God of Gods and the Creator; I am He: Go out from thy father Terah, and get thee out from the house, that thou also be not slain in the sins of thy father’s house.” And I went out. And it came to pass when I went out, that before I succeeded in getting out in front of the door of the court, there came a sound of a [great] thunder and burnt him and his house, and everything whatsoever in his house, down to the ground, forty cubits.[8]

Jubilees 12:1-8:

1. And it came to pass in the sixth week, in the seventh year thereof, that Abram said to Terah his father, saying, 'Father!' 2. And he said, 'Behold, here am I, my son.' And he said,'What help and profit have we from those idols which thou dost worship, And before which thou dost bow thyself? 3. For there is no spirit in them, For they are dumb forms, and a misleading of the heart. Worship them not: 4. Worship the God of heaven, Who causes the rain and the dew to descend on the earth And does everything upon the earth,And has created everything by His word, And all life is from before His face. 5. Why do ye worship things that have no spirit in them? For they are the work of (men's) hands,And on your shoulders do ye bear them, And ye have no help from them, But they are a great cause of shame to those who make them, And a misleading of the heart to those who worship them: Worship them not.' 6. And his father said unto him, I also know it, my son, but what shall I do with a people who have made me to serve before them? 7. And if I tell them the truth, they will slay me; for their soul cleaves to them to worship them and honour them. 8. Keep silent, my son, lest they slay thee.' And these words he spake to his two brothers, and they were angry with him and he kept silent.

Abraham rejected his father's worship of idols, and may have tried to destroy some of them.[9] A human sacrifice was the penalty for desecrating the sacred house of an Egyptian god.

That the penalty of human sacrifice (including burning) was carried out in some circumstances can be shown from a historical account left by Sesostris13 I (1953–1911 BC).14 Sesostris I recounts finding the temple of Tod in a state of both disrepair and intentional desecration, something he attributed to Asiatic/Semitic interlopers he thus deemed as enemies.15 In response, he submits the purported perpetrators to varying punishments: flaying, impalement, beheading, and burning. He informs us that "[the knife] was applied to the children of the enemy (ms.w ḫrwy), sacrifices among the Asiatics."16 Sesostris intended a sacrificial association to be applied to the executions he had just enacted.17 This point is augmented by the fact that some temple sacrifices were consumed by fire.18 While a lacuna makes it impossible to be certain, some of the victims may even have been stabbed with a knife before being burned. In other eras of Egyptian history, this practice of burning seems to have been carried out when ritually slaying a human.19 Clearly, when the sacred house of a god had been desecrated, the Egyptian king responded by sacrificing those responsible.[10]

Daniel C. Peterson:

One noteworthy element of the religious situation portrayed in the Book of Abraham is the identification of a crocodile as the idolatrous god of Pharaoh, right there underneath the lion couch. That’s a kind of odd thing to come up with if you’re a yokel farm-boy from upstate New York. Is that the first thing that comes to your mind? “Oh, idolatrous god of Pharaoh!”

Although this may have seemed strange in Joseph Smith’s day, discoveries in other ancient texts confirm this representation. Unas or Wenis, for example, was the last king of the fifth dynasty, around 2300 B.C., and his pyramid still stands at Saqqara, south of modern Cairo. Utterance 317, Unas’ pyramid texts, includes the following: “The king appears as the crocodile god Sobek, and Unas has come today from the overflowing flood. Unas is Sobek, green plumed, wakeful, alert….Una arises as Sobek, son of Neith. One scholar observes that “the god Sobek is … viewed as a manifestation of Horus, the god most closely identified with the kingship of Egypt” during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom era (around 2000 B.C., maybe a little later), which includes the time period that tradition indicates is Abraham’s time.

Intriguingly, Middle Kingdom Egypt saw a great deal of activity in the large oasis to the southwest of modern Cairo known as the Faiyum. Crocodiles were common there. You know what the name of the place was to the Greeks? The major town there was called “Crocodileopolis.” [11]

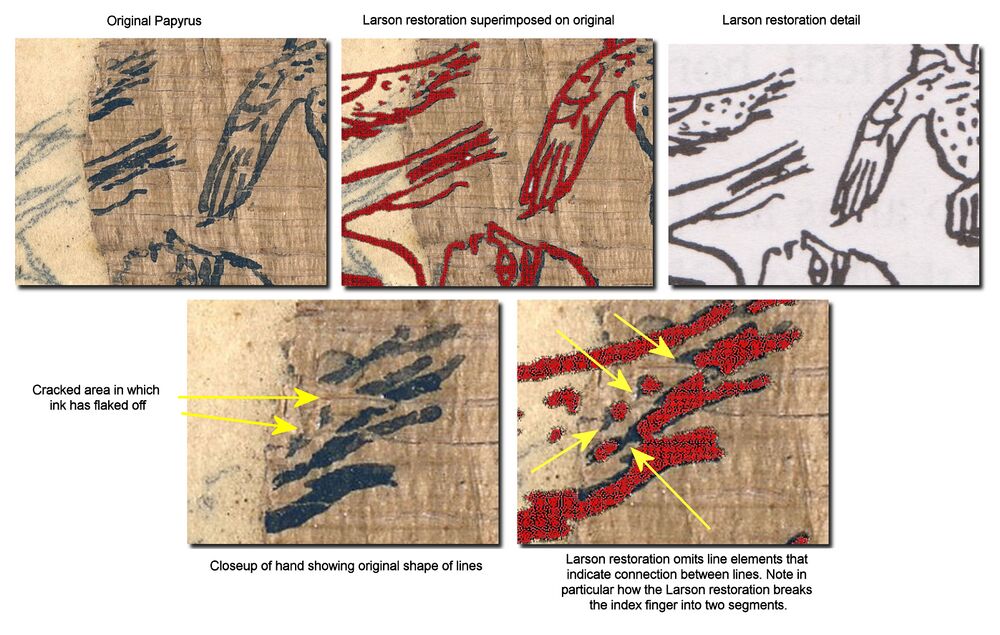

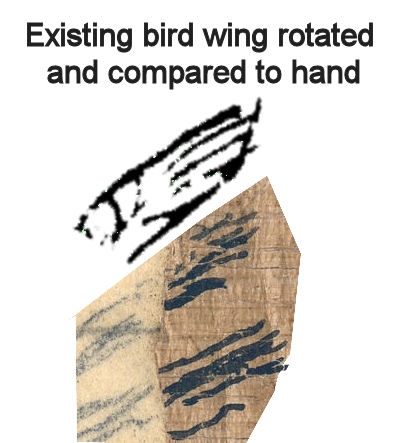

The Larson restoration presumes that the upper hand represented in Facsimile 1 is instead the wing of a bird. There are several elements which disprove this.

Michael Rhodes (2003):

The names of the idolatrous gods mentioned in facsimile 1 provide another example of the validity of the Prophet Joseph’s explanations. If Joseph Smith had simply made up the names, the chances of their corresponding to the names of ancient deities would be astronomically small. The name Elkenah, for example, is clearly related to the Hebrew ttt ‘el q?n?h/ q?neh “God has created / the creator.” Elkenah is found in the Old Testament as the name of several people, including Samuel’s father (see 1 Samuel 1:1). The name is also found as a divine name in Mesopotamian sources as dIl-gi-na / dIl-kí-na / dÉl-ké-na.[21] Libnah may be related to the Hebrew leb?n?h “moon” (see Isaiah 24:23) from the root l?b?n “white.” A city captured by Joshua was called libn?h (see Joshua 10:29). The name Korash is found as a name in Egyptian sources.[22] A connection with K?reš the name of the Persian king Cyrus (Isaiah 44:28), is also possible. [12]

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now