FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

No edit summary |

m (→top: Bot replace {{FairMormon}} with {{Main Page}} and remove extra lines around {{Header}}) |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{Main Page}} | ||

<onlyinclude> | |||

= | {{H2 | ||

|L=Book of Mormon/Warfare/Weapons/Cimeters | |||

|H=Cimeters or Scimeters in the Book of Mormon | |||

|S= | |||

|L1=Hoskisson: "the mistaken assumption that scimitars did not exist in the pre-Islamic Old World" | |||

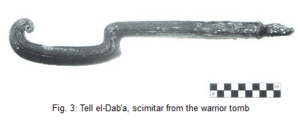

|L2=Egyptian Scimiter from Tell El-Dab'a in the Eastern Nile Delta (circa before 1500 BC) | |||

|L3=Roper: "a strange double-curved weapon held in the left hand of the warrior figure on the Loltún cave relief might be considered a scimitar/cimeter" | |||

|L4=Book of Mormon Central: Why Does the Book of Mormon Mention Cimiters? | |||

}} | |||

</onlyinclude> | |||

{{:Source:Hoskisson:Scimitars, Cimeters:Warfare in the Book of Mormon:the mistaken assumption that scimitars did not exist in the pre-Islamic Old World}} | {{:Source:Hoskisson:Scimitars, Cimeters:Warfare in the Book of Mormon:the mistaken assumption that scimitars did not exist in the pre-Islamic Old World}} | ||

{{:Source: Egyptian Scimiter from Tell El-Dab'a in the Eastern Nile Delta}} | |||

{{:Source:Roper:Swords and "Cimeters" in the Book of Mormon:JBMS 8:1:a strange double-curved weapon held in the left hand of the warrior figure on the Loltún cave relief}} | |||

{{ | {{:Book of Mormon Central: Why Does the Book of Mormon Mention Cimiters?}} | ||

{{FMEBar | |||

{{ | |category=Book_of_Mormon/Weapons/Scimitars | ||

|subject=More on scimitars/cimiters in the Book of Mormon | |||

| | |||

| | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | {{endnotes sources}} | ||

[[ | <!-- PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE --> | ||

[[es:El Libro de Mormón/Arte de guerra/Armas/Cimitarras]] | |||

[[pt:O Livro de Mórmon/Guerra/Armas/Cimitarras]] | |||

Jump to details:

Some critics have termed the presence of scimitars in the text of the Book of Mormon anachronistic. They base their claim on the mistaken assumption that scimitars did not exist in the pre-Islamic Old World and therefore could not have appeared among Book of Mormon peoples who claim an Old World nexus with Iron Age II Palestine.3 This assumption is based no doubt on one or more of the following considerations: (1) the scimitar is not mentioned earlier than the sixteenth century in English texts;4 (2) the Persian word samsir probably provided the etymon for the English word;5 and (3) the mistaken assumption that the period from A.D. 1000 to 1200 saw the "perfection of the Moslem scimitar."6 None of these observations asserts the presence or absence of scimitars in pre-Islamic times. Any arguments to the contrary based on these observations are simply arguments from silence and in this case would result in false conclusions.

There can be no question that scimitars, or sickle swords, were known in the ancient Near East during the Late Bronze Period, that is, about six hundred years prior to Lehi's departure from Jerusalem. There have been several early attempts to demonstrate this,7 but more recently Brent Merrill has convincingly shown that scimitars existed in the Late Bronze Age.8 In addition to the sources Merrill cited, Othmar Keel, on the basis of artifactual and glyptic evidence, dated the use of the scimitar as a weapon in the ancient Near East from 2400 to 1150 B.C., just a little after the traditional 1200 B.C. closing date for the Late Bronze Age.9 Robert Macalister found a late Bronze Age sickle sword at Gezer in Palestine (together with a Mycenaean pot), which Maxwell Hyslop dated to the "14th century B.c."10 Yigael Yadin discussed such swords in the context of warfare in the Near East, including the curved sword in use from Egypt to Assyria during the Late Bronze Age.11. [1] —(Click here to read more)

An Egyptian excavation described a "scimeter," with a picture so labeled:

Matthew Roper: [4]

The possibility has been suggested that a strange double-curved weapon held in the left hand of the warrior figure on the Loltún cave relief might be considered a scimitar/cimeter.[5] Its two blades curve in opposite directions from the ends of a central handle. Grube and Schele consider the object to be a weapon, and it looks something like a special version of the short-sword discussed above. We recall that the date for the figure at Loltún falls within the Book of Mormon period. Moreover, the Izapan art style in which the figure is carved originated in Pacific coastal Guatemala or southern Mexico. That region includes the territory thought by most Latter-day Saint researchers to have been the Nephite and Lamanite heartland. Thus the weapon shown at Loltún has a good chance of being one of the arms that Lamanites and Nephites were using during the central segment of Book of Mormon history. In fact, at Kaminaljuyu, the great ruined city in the valley of Guatemala, which many consider to have been the city of Nephi (or Lehi-Nephi), Stela 11 shows a warrior figure holding a curved object similar to that on the Loltún portrait. It may be even earlier than the one at Loltún, dating to the early Miraflores period (250 to 100 BC). Some Mesoamerican experts consider that the curved object on Stela 11 was the equivalent of the double-bladed weapon at Loltún.[6]

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now