This presentation by Craig L. Foster, a seasoned historian and author of numerous works on LDS history, crime, and the culture of violence, examines the portrayal of a Mormon culture of violence in comparison to broader patterns of 19th-century religious violence in America. Using examples from Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Catholics, Foster refutes claims that Mormonism was uniquely violent and highlights Utah’s significantly lower levels of vigilante justice and extralegal violence compared to other western territories, while addressing modern media misrepresentations such as those in America Primeval and Under the Banner of Heaven.

This talk was given at the 2024 FAIR Virtual Conference, “Understanding and Defending the History of the Church”, in American Fork, Utah on October 12, 2024.

Craig L. Foster is a historian specializing in LDS history, polygamy, crime, and the culture of violence, with numerous publications and seven co-authored or co-edited books.

Transcript

Craig L. Foster

Accusations of a Mormon Culture of Violence

From the time of Joseph Smith to the present, there have been those who have accused the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, its leaders, and members of violence. Indeed, they have declared the Church of Jesus Christ to be a violent faith.

A character in the Hulu series Under the Banner of Heaven dramatically proclaimed, “This faith, our faith, breeds dangerous men.”¹ And Jon Krakauer referred to Mormonism as a violent faith.²

American novelist Wallace Stegner wrote:

To pretend that there were no holy murders in Utah and along the trails to California, that there was no saving of the souls of sinners by the shedding of their blood during the blood atonement revival of 1856, that there were no mysterious disappearances of apostates and offensive Gentiles, is simply bad history.”³

The late Will Bagley stated that Utah’s violence was unique, even in the West, because “it occurred in a settled, well-organized community whose leaders, a growing body of recent scholarship reveals, publicly directed and sanctioned acts of violence.”⁴

The Culture of Violence in Early Mormonism

In his voluminous Sunstone article, “The Culture of Violence in Joseph Smith’s Mormonism”, the late D. Michael Quinn argued that despite accusations of Brigham Young’s violent nature,

Brigham Young did not originate Mormonism’s culture of violence. It had been nurtured by Joseph Smith’s revelations, theocracy, and personal behavior before June 1844.”

He elaborated,

Joseph Smith’s personality and his theocratic teachings were the joint basis for early Mormonism’s norms for violent behavior. This resulted in a violent religious subculture within a violent national culture.”⁵

Criticism of Mormonism’s Unique Culture of Violence

While suggesting that Mormonism’s so-called culture of violence was out of character with other religious denominations of the time, John Dehlin wrote,

Other isolationist sects in the region, such as the Mennonites and Shakers, managed to live peacefully within their communities. The Mormons experienced this combative culture with their neighbors largely due to their propensity to vote in nearly unanimous blocks and raise well-armed militias.”

Dehlin also stated,

The strong theocratic (government ruled by religion) philosophies of Joseph and Brigham furthered violent Mormon culture. Mormons violated territorial boundaries and peace agreements, championed Zionist ideals in fiery speeches, threatened non-Mormons, and boasted of their regional political power.”⁶

Defending ‘Violence Against Evil’

Quinn wrote,

Violence against ‘evil’ became a defensible rationale for both the Smith family and for most early Church members.”⁷

And of those early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who did not partake in violence, Quinn asserted,

The fact that many Utah Mormon men did not act upon the norms for violence that Brigham Young and other general authorities promoted is beside the point. Those violent norms were officially approved and published by the LDS Church in pioneer Utah.”⁸

Addressing the Question of Violence

Such pronouncements and accusations demand an answer to the question: Were the early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints really a violent religious subculture within a violent national culture, and were they more violent than their religious counterparts?

This paper will attempt to answer this important question, looking specifically at indications of a culture of violence among other religious denominations of nineteenth-century United States.

American Christianity and the Culture of Violence

A number of historians have written about a culture of violence that permeated nineteenth-century American society and was particularly manifested in certain cultural regions such as the South and the West. While it is expected that violence was more common among men, there were examples of women also sanctioning and even participating in acts of retributive violence.⁹

It was within this milieu that The Church of Jesus Christ and other Christian denominations existed. Religion and morals espoused by most of the churches at the time were generally supported,

but that morality incorporated violence. Men of God did not hesitate to use violence, and society followed their lead.”¹⁰

Religion and Violence Intertwined

Thus, in certain American regions and among some religious classes,

Religion and violence were closely intertwined … They symbolized the struggle between good and evil in individuals and in society.”

For example, among the Black Patch people of western Kentucky and Tennessee,

they took such teachings as ‘an eye for an eye’ literally and used them to justify brawling and even vengeance.”¹²

Such attitudes also reflected

emotional Southern religion and the contemporary frontier culture.”¹³

The “eye for an eye” approach to religion and society, expressed by many in different regions of the United States, especially on the frontier, continued the culture of violence. Despite attempts to reform such habits, they appeared to have remained throughout the nineteenth century and even into the twentieth century:

The Great Awakening’s attempt to reform the violent habits of men was significant, but throughout the South eye-gougings and nose-bitings continued to be a part of everyday life.”

Without constant effort and reminders, people backslid into old habits. Despite efforts to change old habits,

the manly ways of the backcountry survived the Great Awakening.”¹⁴

Violence as a Tool of Moral Enforcement

Such violent habits were expressed against institutions and individuals “who violated [the community’s] notions of moral behavior.”

An example was the Hardin, Missouri preacher who thrashed a newspaperman with whom he had a problem. He justified his act by quoting Psalms 144:1, “Blessed be the LORD, my strength, Who teacheth my hands to war, And my fingers to fight.”¹⁵

Religious Leaders and Vigilantism

These religious leaders were not alone in their extralegal punishment of real and perceived miscreants. An 1857 eastern Iowa vigilance movement was presided over by a Rev. Ewald Cooly, with Rev. A. McDonald serving as the treasurer. Additionally, two ministers were among Socorro, New Mexico’s vigilantes.¹⁷

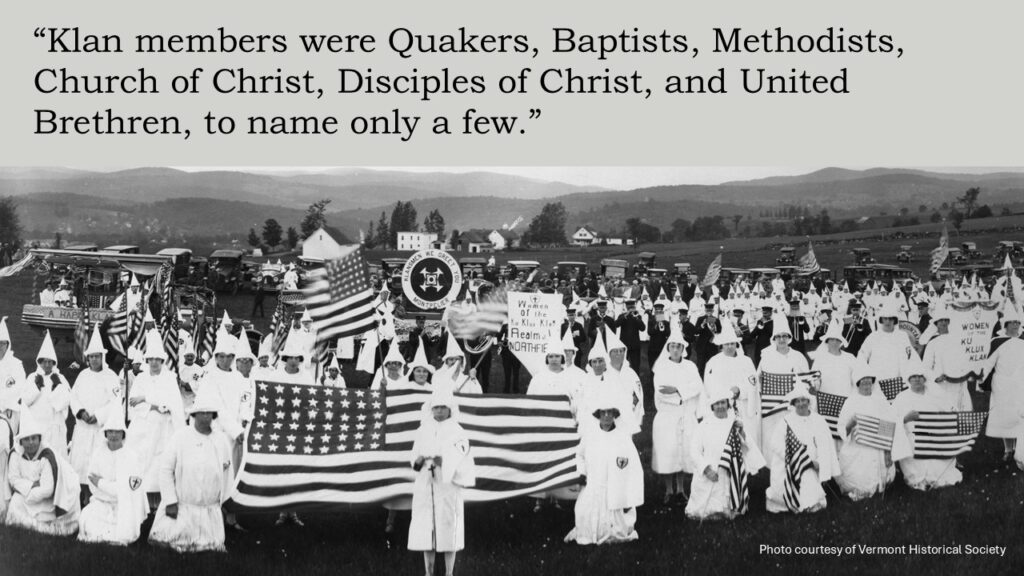

During the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many Southern ministers either condoned or turned a blind eye to the Klan’s violent activities.¹⁸

The Ku Klux Klan had a broader appeal to white Protestants, particularly evangelicals. Due to various fears, white evangelicals readily accepted the Klan and its racial violence.¹⁹

Like their nineteenth-century counterparts, Klan members of the 19teens and 1920s, “embraced Protestant Christianity and a crusade to save America from domestic as well as foreign threats.” Twentieth-century “Klan members were Quakers, Baptists, Methodists, Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ, and United Brethren, to name only a few.”²⁰

Baptists

Baptists, particularly Southern Baptists, incorporated a culture of violence that continued throughout the nineteenth-century and continued well into the twentieth century. The First Great Awakening came to the South, and evangelical religion tried to stamp out fighting and violent rituals so common among the backcountry plain folk. Evangelical culture [Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, among others] preached against violence. And “many converted plain folks abjured the violence of their region and embraced an evangelical ideology that stressed self-control and self-denial over boldness and indulgence.”

Peaceful interaction was taught and encouraged by preachers.

“Baptist churches [continued to encourage] men to reject the honor-bound, violence-driven values of old in favor of a self-controlled evangelical manhood.”²¹

Despite efforts to pacify and transform portions of the Baptist population, it was difficult to do so. This wasn’t helped when the preachers were at times the problem. For example, James N. Pace was robbed while on a steamboat. Angered at being robbed, he led a mob with the intent to hang all involved. One man was shot several times, tried to escape by jumping overboard where he drowned.²²

In Nebraska, a Baptist preacher named Byerd was tarred and feathered by a mob that included members of his congregation because he had beaten his daughter when she informed her mother of the preacher’s adulterous relations with other women.²³ In Gratz, Kentucky, the wife of a prominent Baptist preacher whipped a Methodist preacher for circulating slanderous stories about her.²⁴

Infighting Among Preachers

It doesn’t end there. In 1883, in Hartford, Connecticut, the Reverend Everts and Reverend Dr. Parker began fighting. The two preachers beat each other, tore out hair, and fell into the font and tried to drown each other.²⁵ That same year, the annual camp meeting of Bethel Church in North Carolina was broken up when a large fight broke out between Reverend Edwards and his supporters and Reverend Jones and his supporters.²⁶

Ku Klux Klan Involvement and Vigilante Activity

The less than saintly behavior of some Baptist leaders didn’t stop there. As already mentioned, there was a significant Baptist representation among members of the Ku Klux Klan and other vigilante-type groups.²⁷ Klan membership included Baptist clergy. For example, John S. Ezell, a prominent Baptist minister in Spartan County, South Carolina, joined the Klan “because nearly everybody else in the county belonged to it, and he thought it a good thing.”²⁸

Ezell was arrested for his Klan activities, and during the trial, he admitted that most of his congregation were Klan members. He also replied to a question about other clergy being members. He said he didn’t know of any. When asked about the Reverend Mr. Carpenter running away to avoid arrest, Ezell answered, “Oh, yes, but he is a Methodist. I am a Baptist minister.“²⁹

During the Black Patch Tobacco War of western Kentucky, the Night Riders were violent vigilantes made up of tobacco farmers. In one incident, a family was attacked. The wife was injured while trying to protect her baby, and the husband,

bent to the lashes on his bare back, which streamed blood. A ‘highly respected member of the community, a pillar of the Baptist church, applied the stripes. A woman member of the band exclaimed, this is sweet revenge to me.’”³⁰

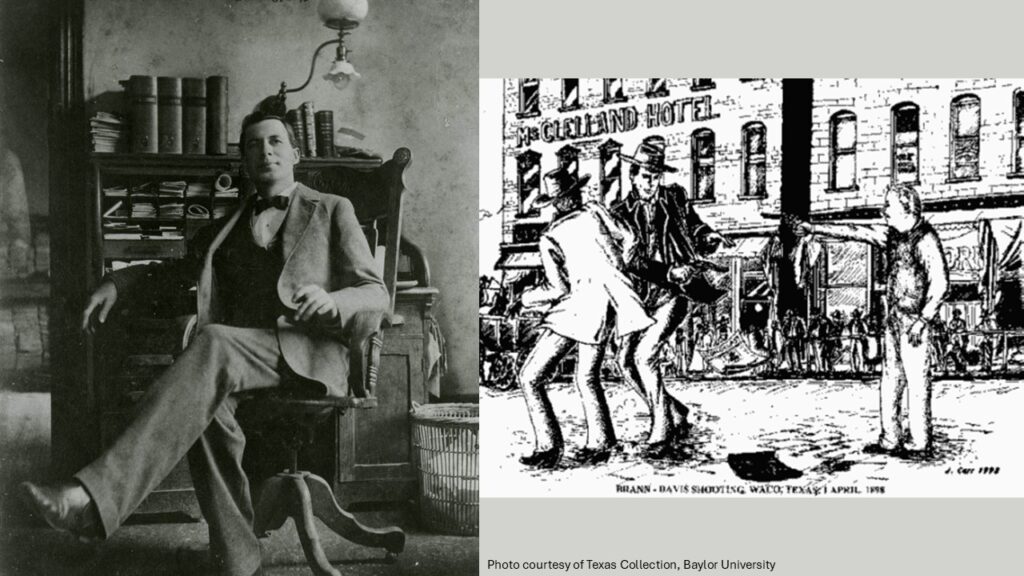

Baylor University Scandal

One more example dealing with Baptist violence involves a rape scandal at Baylor University, a Baptist-owned and run institution in Waco, Texas, in the late 1890s. In 1895, journalist William Cowper Brann moved to Waco to restart his Iconoclast magazine. Among his favorite targets were Baptists, especially the Baptists at Baylor University. He once wrote, “I have nothing against the Baptists, I just believe they were not held under long enough.”

So regular were Brann’s attacks against what he viewed as Baptist hypocrisy, for “Bran despised hypocrisy, which he found in abundance in Waco,” that a prominent Baptist called Brann “the Apostle of the Devil.” Brann wore the moniker with pride.³¹

Waco, a city of 24,000, had 14 Baptist churches and 3 Baptist magazines. In June 1895, a Waco newspaper published a story about Brazilian native Antonia Teixeira (age 13-14) being pregnant. She had been living in the household of Dr. Rufus Burleson, president of Baylor University. She claimed she had been raped several times by H. Steen Morris, Burleson’s son-in-law’s brother. Brann picked up the story and wrote a series of articles about the developing scandal. He claimed that Teixeira “was not the first young girl to be sent from Baylor in disgrace” nor

“the first to complain of assault within its sanctified walls.”

He called the university a manufacturer of “ministers and Magdalenes” (i.e., fallen women). Baylor and Baptist officials attacked the girl’s reputation, with one calling her a “foul prostitute” and “child harlot” despite the evidence against Morris. A Waco jury failed to convict Morris, and Antonia Teixeira was bought off and moved back to Brazil.³²

Escalation of the Baylor University Controversy

After Teixeira left, Brann predicted Baylor would “carefully lock the closet in which it keeps its interesting collection of skeletons.”

The scandal resulted in Burleson being forced to resign as Baylor president. However, it didn’t stop there. On October 2, 1897, William Brann was kidnapped from his office by four Baylor students, tied up, and taken to campus. A mob of at least 200 students awaited, and Brann was beaten, spat on, threatened with a gun and a hangman’s noose, and forced to sign an apology and promise to leave town. Many believe that, had two Baylor faculty members not intervened, Brann would have “dangled from a campus oak tree.“³³

Just four days later, Brann took another thrashing, this time at the hands of Baylor trustee Judge John Scarborough and his son, George. The Scarboroughs were enraged at Brann’s “Magdalenes” remark, as the elder Scarborough’s daughter was then a Baylor alumna and English instructor. While the son held Brann at gunpoint, the father laid into him with a cane. One of the student ringleaders of the previous incident happened by right then and joined in the fun, lashing Brann with his horsewhip, shouting, “So you wouldn’t leave town, eh?“³⁴

A Violent Climax

The controversy continued. Brann ally Judge George “Big Sandy” Gerald got into a scuffle with Waco Times-Herald editor James Harris. Harris “crowed about the tussle.” Gerald called Harris “a liar, a coward and a cur” and challenged him to a duel. A few days later, Gerald saw Harris and advanced on him. Both Harris and his brother, Bill, who was standing across the street, started shooting at him and wounded him in the left arm. George kept advancing and killed Harris with a single shot.

The bleeding Gerald then staggered across the street and shot Bill through the head.”

Witnesses all agreed that the Harrises fired first, and Gerald was acquitted of their murders and re-elected in 1900 as a district court judge.

The final act in this unfolding melodrama took place on April 1, 1898. Brann and his business manager were walking to the train station. Real estate developer and Baylor supporter Tom Davis stepped out of his office and shot Brann in the back. The business manager scuffled with Davis while Brann shot Davis several times. Both Brann and Davis died of their wounds.³⁵

Congregational Church Incident

In 1892, in Jennings, Louisiana, the Reverend E. A. Bridger was whipped while preaching from the pulpit. He was whipped by a prominent citizen and member of his congregation because he had repeatedly publicly stated that “the women of the place were unchaste and the whole town was a cesspool of iniquity.“³⁶

Dutch Reformed Church

The church on Forsyth Street, New York City, was the scene of one of “the most disgraceful riots, rows, and fisticuffs, on Sunday, that ever graced a groggery.”

The congregation was divided over the minister—whether the preaching should be in Dutch or a combination of Dutch and English. It came to fighting, and there were “bloody noses, ragged coats, split pantaloons, smashed bonnets, torn frocks, and black eyes…“³⁷

German Protestant Church

The German church in the fourth district of New Orleans divided, with a minority supporting the minister and the majority bitterly opposing him and forbidding him to officiate. He went into the church, and the women descended upon him like an avalanche, with cowhides, pepper, salt, flour, and gypsum, “lathering him mercilessly with the former articles, and powdering him all over with the latter.”³⁸

Lutherans

During the 1740s, Lutheran conflict with and violence against Moravians “raged from Virginia to New York, but it was most intense in the German and Swedish communities of Pennsylvania and New Jersey.“³⁹

Indeed, the Delaware Valley was a particular hot spot of violence.

The Lutheran anti-Moravian conflict became particularly violent in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in late 1745 and early 1746 when about seventy Lutheran families, stirred up by their ministers, “attacked [and] fought with about eighty pro-Moravian families in a riot that turned into a violent altercation.”

From that point, both sides resorted to carrying weapons to church services, and similar violent altercations spread to a number of communities. “After years of sometimes violent controversy, the Moravians and Lutherans eventually developed as separate denominations.“⁴⁰

While inter- and intra-denominational conflict involving Lutherans decreased significantly after that volatile eighteenth-century decade, divisions and discord still occurred.

In 1837, a riot took place at a Lutheran church in New York City over theological issues and ritual. The conflict was between Lutherans and Calvinists, and a melee occurred around the pulpit, with congregants “thrashing each other like loafers at the Five Points” in reference to the infamous Five Points gangs.⁴²

In 1851, another riot took place between two factions of the Chillicothe, Ohio Lutheran church, who resorted to fisticuffs. Among those injured was the wife of the pastor, and a man was arrested for assaulting her.⁴³

Famous frontier Methodist preacher and one of the first two Methodist bishops in America, Francis Asbury, once said,

It is true that Methodists are not a fighting people, but they are not all sanctified—they may be provoked to retaliate, and they are very numerous on this ground.”⁴⁵

Historically, there appears to have been a number of Methodists provoked in one way or another.

Violence Among Methodist Clergy

One of the more colorful examples was Eli Farmer, an antebellum Methodist clergyman who not only preached violence but also practiced it. In the mid-1830s, he confronted an antagonistic neighbor and “thrashed” him.

The man continued to verbally abuse Farmer, who finally “caught him by the throat and running him against a fence choked him til his tongue protruded and he began to beg.”

Farmer and other nineteenth-century

circuit-riding Methodist clergymen from Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio included many similar boastful and at times gory accounts of their willingness and ability to dish out physical beatings to various antagonists.“⁴⁶

A Methodist Sunday School superintendent in the Ohio Valley organized a posse to track down a tramp who had stolen a knapsack full of Bibles and then insisted the man be punished immediately rather than going to the trouble of binding him over for a trial. The thief received thirty-nine lashes.⁴⁷

Methodist clergyman Peter Cartwright could be combative, even violent, in the course of his circuit-riding duties because

the reminiscences of his early career in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio are seemingly little more than a succession of battles with evangelical rivals, of whom Baptists are the principal foe.“⁴⁸

Cartwright one time told about how some Latter-day Saints had disrupted a camp meeting over which he presided. He ordered them out, yelling, ‘Don’t show your face here again, nor one of the Mormons. If you do, you will get Lynch’s law.’

In short, the preacher threatened to kill any Saints who dared to show their faces at a Methodist meeting.⁴⁹

Intra-Denominational Violence Among Methodists

Like other religious denominations, Methodists also fought amongst themselves. In Fannin County, Texas, in 1859, members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, North were ordered to leave the conference by about fifty members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. They were threatened to have “lynch law applied to them” if they did not leave.⁵⁰

Along the lines of mobbing and disruption, Methodist Episcopal Church revivalist preacher Samuel Porter Jones encouraged the mobbing of a theatrical group in 1884 Newnan, Georgia, while a Methodist preacher caused a riot between Methodists and Catholics in Axtel, Kansas, in 1889.⁵¹ A Reverend Frazell was cowhided (whipped) in Elmwood, Illinois, by an incensed member of the congregation because he had insulted her during a temperance meeting.⁵²

Escalation to Deadly Violence

For some Methodists, including religious leaders, acts of violence extended beyond simple fighting, whipping, and even rioting. In Virginia, a Methodist preacher named R. S. Bigham was assaulted by three men he had ejected from a previous church meeting. He pulled a pistol and shot one man. The other two escaped.⁵³

A year later, in Greene County, Missouri, Reverend John Calvan shot and killed William Herdick, a deacon in his congregation, and shot and wounded Herdick’s brother-in-law. Herdick suspected the minister of committing adultery with his wife. Herdick attacked his minister with a knife, and Calvan responded by firing his pistol.⁵⁴

In another deadly incident, the Rev. B. Jenkins, of Mansfield, Louisiana, having, it is said, reason to believe that the Rev. J. Dane Bowden, President of Mansfield College, had seduced a young lady friend of his, shot Bowden ‘on sight,’ putting six bullets in his body. Both were ministers of the Methodist Episcopal Church.⁵⁵

In late 1763, the Scotch-Irish Presbyterian Paxton Boys, as they called themselves, massacred a group of Christian Susquehannock Indians near Lancaster. Nearly two dozen were killed in the attack.

A larger group of Paxton Boys Scotch-Irish marched on Philadelphia in early 1764 with the aim of killing the Moravian Lenape and Mohican Indians, who had been moved to Philadelphia for their protection.

Benjamin Franklin rallied a militia that stopped the Paxton Boys outside the city, but the incident sparked much political tumult, especially between Quakers and Presbyterians who were labeled ‘Piss-brute-tarians (a bigoted, cruel and revengeful sect).’”⁵⁶

Furthermore, the Paxton Boys and their Presbyterian supporters were accused of targeting not only Native Americans, but also whites, English Quakers, and German Moravians believed by Scotch-Irish settlers to threaten the safety of the backcountry.⁵⁷ While the incident was resolved, animosity between Presbyterians in Pennsylvania against Quakers and Anglicans continued for some time.

In Reconstruction South Carolina,

Leaders of the Bethesda Presbyterian Church in York County, an area of heavy Klan violence, voiced exasperation [not at the Ku Klux Klan and violence, but] over federal intervention and mass arrests.”⁵⁸

In New Orleans, a Presbyterian minister, like some of his Methodist counterparts, used a gun to solve his problems. Cumberland Presbyterian minister Reverend J. J. Wilson was having an argument with James Howell. Wilson grabbed a shotgun and fired at Howell but missed him. Howell returned fire and killed Reverend Wilson.⁵⁹

Violence Among Other Denominations

There are other examples of varying degrees of culture of violence among denominations and congregants. Indeed, even the well-known pacifist Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, had their incidences of unpleasantness. This was particularly the case during the Hicksite schism over theological issues dealing with the Bible and Jesus Christ.⁶⁰

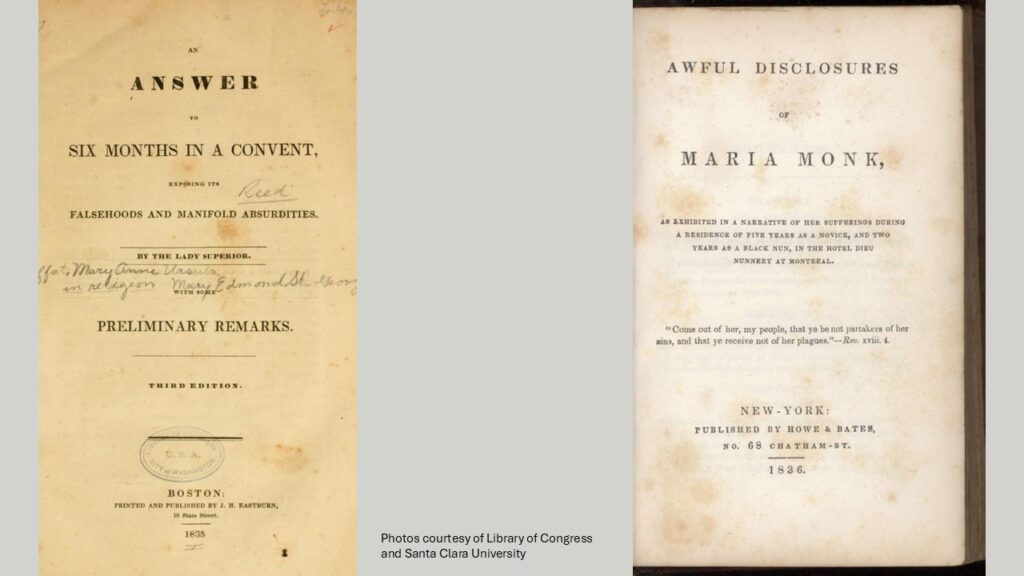

This took place before the publication of two popular anti-Catholic works published in 1835: Rebecca Reed’s Six Months in a Convent and Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu.

The burning of the convent actually encouraged the publication of such escape exposés as the two mentioned works.⁶³

Anti-Catholic Riots

Among the antebellum anti-Catholic riots engaged by Protestants were the 1841 New York City riots, caused by anger that the governor was going to give some school fund money to support Catholic schools. One newspaper warned the governor’s actions would “open up all the religious violence of the darkest Popish ages of Roman religious tyranny, [and] may create riots and bloodshed,” which it ultimately did.⁶⁴

Among other anti-Catholic riots were two in Philadelphia (1844) and one in Boston (1834), and anti-Catholic feeling was behind Cincinnati’s Bedini riot of 1853.⁶⁵ The Philadelphia riots of 1844 were caused by Catholic demands for religious free exercise and the right to education. They became known as the Bible riots:

As Catholics publicly demanded rights to freedom of conscience, and rights to decide the form of education in public schools, the Protestant majority pushed back by violently asserting traditional boundaries around who could act as citizens.“⁶⁶

These anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic riots of 1844 caused violence against Irish residents and resulted in two burnt Catholic churches in the neighborhoods of Southwark and Kensington in Philadelphia.⁶⁷

Impact of Anti-Catholic Propaganda

Not only did tell-all exposés like Six Months in a Convent and Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu impact Protestant perception of Catholics, but lectures by former Catholics, especially those claiming to be former priests or nuns, were also used to stir up Protestant fear and anger.

For example, in Bath, Maine, in 1854, a person going by the name of the “Angel Gabriel” gave an impassioned lecture. Following the lecture, a mob of men and boys proceeded to the Old South Church, used by Catholics as a place of worship, and burned it to the ground. The mob then paraded through the streets, yelling and hooting.⁶⁸

Catholic Riots and Mobbing

Despite this history of persecution, Catholics appear to have been able to give as well as they received. The 1842 Lombard Street Riot happened when

more than 1,000 members of the black Young Men’s Vigilant Association took part in a temperance parade to commemorate the eighth anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the West Indies”

and were attacked by an Irish Catholic mob.⁶⁹ The riot, caused in part by social and economic competition of the growing black population, caused serious damage, including the burning of the African Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia.⁷⁰

In 1852, a Catholic mob broke up the Baltimore lecture of the Reverend Mr. Leahy, who claimed to be an ex-monk. The following evening, the Catholic mob again tried to break up the lecture but were thwarted in their efforts. The Washington D.C. newspaper reporting the mobbing proclaimed,

The Pope may reestablish the Inquisition in Spain, and make bonfires of Protestant books in Italy, and suppress Protestant worship in Rome, but his friends in this country must be admonished that we live in a different dispensation.“⁷¹

Threats and Violence Against Protestants

More Catholic mobbing was threatened in 1871 Newark, New Jersey, when a Baptist minister baptized a Catholic girl.⁷² In 1894 Québec City, Canada, a mob of approximately 500 people attacked the French Baptist Mission headquarters, causing serious damage to the building. They then attacked the headquarters of the French Anglican Mission and also attacked the Salvation Army Barracks.⁷³

The Slattery Anti-Catholic Lectures

In the mid-1890s, a husband and wife named Joseph and Mary Elizabeth Slattery, claiming to be a former priest and nun, gave a series of anti-Catholic lectures. In October 1893, in St. Louis, Missouri, they were accosted by a mob of Catholics who were yelling, “Lynch him!” and “Teach him a lesson!”

Police had to be called to protect the couple.⁷⁴ In San Francisco, a mob of 10,000 people gathered where the couple was lecturing. They were crying, “Lynch him!” “Hang him!” “Kill him!” but the couple were protected by members of the American Protective Association.⁷⁵

Probably the most violent protest of the Slatterys took place in February 1895, in Savannah, Georgia, where they were lecturing. The Ancient Order of Hibernians had petitioned the mayor to not allow the couple to lecture in the city, but their appeal was rejected. The morning of the lecture, four three-story buildings were blown up and destroyed.

That night, the mob of three to five thousand, most of them Catholics, surrounded the lecture hall and began making threats while throwing bricks, rocks, and other projectiles. Those attending the lecture were unable to exit the building for fear of being attacked. Eventually, eleven military companies had to be called out to disperse the mob.⁷⁶

Normative Violence in Early America

Thus, the various Christian denominations in America reflected what D. Michael Quinn described as

pervasive, often normative, in early America. Much of this normative violence reflected the national society, while regions (such as the South and the West) had their own traditions of sanctioned violence in daily life.“⁷⁷

How Violent Were Mormons and Was Mormon Utah?

While there are certainly examples of violence among Christian denominations, the question still must be asked:

“Was there a strain of violence within nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint culture as violent as and perhaps more so than that of most Americans around them?”

Critics of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints point to a few well-known acts of extralegal violence as evidence of a culture of violence that permeated the early Church.⁷⁸

Critics and naysayers point to certain points and events to push their argument of “a violent religious subculture within a violent national culture.“⁷⁹

Naturally, the Mountain Meadows Massacre is usually the first mentioned, followed by accusations of blood atonement and extralegal justice as examples of a Mormon penchant for violence. The Mountain Meadows Massacre was an unbelievably horrible tragedy that took place in extraordinary circumstances and was generally an anomaly in Mormon history.⁸⁰

Blood Atonement and Vigilante Violence

But what of accusations of blood atonement, as well as known acts of vigilante extralegal violence that included lynchings, shootings, and even a couple of cases of castration? Where did such incidents place within the greater historical and social context of the time?

As stated above, “the fact of American violence is that, time and again, it has been the instrument not merely of the criminal and disorderly but of the most upright and honorable.”

This is because traditionally, “Americans have never been loath to employ the most unremitting violence in the interest of any cause deemed a good one.“⁸¹

Such was the case not only for various religious denominations, but for the United States as well. The states and territories surrounding Utah experienced differing levels of vigilantism and extralegal violence. For example, when it came to vigilante justice, “the states and territories of the plains and mountain West showed comparable patterns of vigilante justice.“⁸²

Communities allowed the violent nature of these groups and supported them because of the need to curtail the high level of criminality in western settlements. All levels of society were involved in these groups.

Vigilante groups were comprised of merchants, bankers, saloon owners as well as women who would be the eyes of the town.“⁸³

Comparing Utah to Other Territories

Vigilantism was rampant in Nevada mining towns from Virginia City to Pioche.⁸⁴ Montana was a significant vigilante state. The 1884 vigilante movement in northern and eastern Montana against horse and cattle thieves “claimed thirty-five victims and was the bloodiest in all American vigilante movements.”

Texas had fifty-two vigilante movements—more than any other state.

There were dozens and dozens of vigilante movements in most of the other western states; only Oregon and Utah did not have significant vigilante activity.“⁸⁵

Even Brigham Young biographer John Turner, while discussing aspects of Mormon violence, acknowledged the fact that

“Utah was remarkable for its lack of organized vigilante activity.“⁸⁶

Another historian noted,

Violence in America has long manifested this uneven quality [of levels of violence]. Some regions, such as the South and the frontier and urban ghettos, have experienced very high levels of violence and disorder, while others, such as rural New England or Mormon Utah, have been far more tranquil places.“⁸⁷

The lack of extralegal violence in Utah compared to other territories is impressive, as such incidents

were very rare compared to elsewhere in the West, where no concerted effort to undermine a popularly supported government was going on as in Utah [by the federal government versus the Mormons].“⁸⁸

Violence in Utah: Context and Criticism

Nevertheless, we do need to affirm that “Utah was far from devoid of violence, both legal and extralegal.“⁸⁹

But most of Utah’s violence took place on the fringe of frontier society.

Lawless violence on the frontiers of the Mormon kingdom was predictable as strangers and outlaws converged in the unordered periphery of civilization. Unlike the territorial frontiers, the heart of the Utah Territory was a society founded and established on law, with communities full of individuals that interacted on a daily basis.“⁹⁰

Utah: An Oasis of Civilization

Utah was considered an oasis of civilization in a very large stretch of desert and mountains. And, despite the charges that non-Mormons were not safe anywhere in Utah Territory,

The majority of Utah citizens were tolerant of migrants, visitors, and settlers who were of different religious persuasions. One early observer noted that the Mormons were ‘not an intolerant people;’ rather, they were deeply misunderstood.“⁹¹

Brigham Young’s Teachings on Blood Atonement

Still, both critics and members of The Church of Jesus Christ have pointed to Brigham Young’s teachings about blood atonement as an example of Mormon violence. Brigham Young and other leaders preached about how some sins, like murder and adultery, were so grievous that they could only be atoned for by the spilling of blood. In one speech, Young said,

Any of you who understand the principles of eternity, if you have sinned a sin requiring the shedding of blood, except the sin unto death, would not be satisfied nor rest until your blood should be spilled.“⁹²

While this language appears shocking to twenty-first century ears, the nineteenth-century style of preaching was known for being fiery and often filled with violent rhetoric. Paul H. Peterson referred to Brigham Young’s blood atonement teachings as rhetorical devices, and Ronald W. Walker argued that Brigham Young and other early church leaders used harsh language that was

like having ‘it raining pitchforks, tines downwards’ and the sermons akin to ‘peals of thunder,’ but more as rhetorical devices to encourage Saints to repent, rather than as a carte blanche to commit blood atonement or other forms of holy violence.“⁹³

Understanding Blood Atonement in Context

In terms of blood atonement and holy violence, historians have found that “there was little bite accompanying Young’s celebrated bark.“⁹⁴

For, “Herein was the true nature of blood atonement—to allow men to realize the gravity of their sinful ways and rechart a course towards salvation through good works.“⁹⁵

Thus, Brigham Young repeatedly told penitent sinners, including adulterers and others who had committed grievous sins,

“to not seek to have their blood shed but to simply repent and do better.“⁹⁶

Despite Young’s and others’ forgiving approach to penitent sinners, as well as the fact that actual blood atonement killings were extremely rare and even harder to substantiate, stories abounded of blood atonement killings throughout Utah. Many people spoke in generalities but were unable to actually provide evidence of blood atonement murders.⁹⁷ Lack of evidence notwithstanding, warnings of holy murders and people not being safe in Utah continued.⁹⁸

Violence in Utah: A Misunderstood Narrative

The reality is most

extralegal violence in Utah did not revolve around, nor was it dependent upon, the idea of blood atonement. The evidence clearly indicates that the majority of these incidents were the direct result of vigilante-style justice. It has been claimed that it ‘would be bad history to pretend that there were no holy murders in Utah.’ It is equally deficient to allow an extremely misunderstood doctrine to distort the past of an entire people and region.“⁹⁹

And it has already been shown that vigilante extralegal violence in Utah was at a much lower rate than surrounding places. As Thomas G. Alexander explained,

The available evidence shows, however, that beyond a few well-publicized murders, we have every right to believe that compared with surrounding territories, Utah was a relatively murder- and violence-free community. … In fact, barring further evidence to the contrary, the best evidence we have at this point is that Utah was one of the least violent jurisdictions in the western United States.“¹⁰⁰

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper has not been to cast aspersions upon the named denominations nor their members. Nor is it to justify incidents of violence among and by early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The purpose of this paper is to answer the question of whether or not the LDS Church and its members really were a violent religious subculture within a violent national culture and were even more violent than their religious counterparts.

When looking at the larger picture, the answer to the question is that it’s obvious The Church of Jesus Christ and its members were not more violent than their religious counterparts. For that matter, in most cases, it appears they were less violent than some members of other religious denominations, as demonstrated with the examples given.

The reality is, as historian Patrick Q. Mason explains,

all religious traditions have within them multiple and often conflicting resources such as scripture, rituals, leadership structures, and cosmologies that lead ‘some religious actors [to] choose the path of violence while others seek justice through nonviolent means and work for reconciliation among combatants.’”¹⁰¹

Furthermore, when dealing with humans and humanity, inevitably there will be a mix of everything in terms of action and reaction. Because of human nature, we need to

“recognize the tragic elements within every religious community’s past.“¹⁰²

Despite moments of difficulty and even certain levels of anti-social behavior or violence, it’s difficult and even a bit ridiculous to judge and condemn a whole religious movement for the actions of a few individuals or even small groups within that organization or denomination.

Thank you.

Q&A Transcript with Craig Foster

Scott Gordon: So that was really interesting. I think it’s interesting that the Church tends to be portrayed as violent, or it’s always tied to violence. Why? Why do you think that is? What do you think—what’s the motivation for those ties to that particular thing?

Craig Foster: Well, I think, I think one of the motivations is to—if they are able to portray the Church, especially the early Church, as being these religious, you know, crazed radicals, then it calls into question the veracity of the gospel message. And if they’re able to portray Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and some of the other leaders as being violent, then it doubly calls into question the veracity of the gospel message.

Scott Gordon: Makes it so…we try to turn—can’t talk here—makes it, puts us in a non-Christian category. Right?

Craig Foster: Exactly. We become one of the “others.”

Scott Gordon: Got it. Well, here’s a question we have. Would you likely attribute the violence cited as not necessarily endemic to the sects noted in your remarks? I think what they’re saying is you listed a number of violent acts by various other denominations, but you would agree that the same thing for us holds true with them as well?

Craig Foster: Absolutely, absolutely. I wanted to give examples from other denominations to show that we need to put it within the greater historical and social context. And so that wasn’t to make the other denominations look bad. The reality is, humans are going to be humans, and we have a very violent culture today, but we have a culture that doesn’t accept violence as much as the earlier culture did.

In other words, we have a violent culture—we have it on TV, we have it in movies everywhere—but we still are able, for the most part, to say, That’s bad, that’s wrong. Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was almost expected. In fact, I’ve argued in other articles dealing with the culture of violence that, in many ways, it was not only accepted, it was expected that should someone feel insulted or wronged, they would attack physically, violently. Hopefully, nowadays, we don’t have that attitude as much.

Scott Gordon: I think also, we had a society back then in the 1800s where we did not have—and we always see the sheriff in town and things—but a lot of communities didn’t really have that. And so people used extralegal methods to maintain peace, as they put it.

Craig Foster: Exactly. And I have, in the fuller article, mentioned the fact that vigilante groups included everyone. Basically, you would have shop owners, bank owners—you name it. There’s a phrase that I’m going to slaughter here, but it’s a famous phrase about justice by the hands of upstanding individuals.

In other words, when these vigilante acts took place, it was some of the finest people in the community who did the vigilante acts or encouraged them. So that was their way of trying to have a type of law and order if they felt that the actual law was not doing the job or wasn’t present.

Scott Gordon: And I know that you’ve spoken out before about this subject many times, including—you spoke out quite strongly when the Under the Banner of Heaven series came out.

Craig Foster: Yeah. Yes. Because, once again, both Krakauer and then especially the series—I thought Krakauer was bad, but my heavens, the series—they tried to drum up every imaginable thing. And if you pull something out of historical and social context, you can paint a person or a group of people any way that you want. And both Krakauer and the Under the Banner of Heaven series did that.

Scott Gordon: Okay. Thank you so much for your time.

Craig Foster: You’re welcome.

End Notes

1 Under the Banner of Heaven, season 1, episode 1, “When God Was Love,” directed by David Mackenzie, written by Duston Lance Black, aired April 28, 2022, on Hulu, as quoted in Craig L. Foster, “What Under the Banner of Heaven Gets Wrong,” 2022 FAIR Conference, August 2022, https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august 2022-fair-conference/what-under-the-banner-of-heaven-gets-wrong#_edn25, accessed July 4, 2024.

2Jon Krakauer, Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith (New York: Doubleday, 2003).

3 Wallace Stegner, Mormon Country (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1942, 2003), 96.

4 Will Bagley, “’The Servants of God Will Come Forth to Slay the Wicked’: Apples and Oranges—What Was Different about Violence in the Mormon West?” 2009 CESNUR International Conference,

https://www.cesnur.org/2009/slc_bagley.htm#_ftn7.

5 D. Michael Quinn, “The Culture of Violence in Joseph Smith’s Mormonism,”

Sunstone, 19 October 2011, https://sunstone.org/the-culture-of-violence-in-joseph-smiths-mormonism-part iii/#_edn40.

6 John Dehlin, “Violence in Mormonism,” 17 October 2023, https://www.mormonstories.org/truth claims/mormon-culture/violence-in-mormonism/.

7 Melvin T. Smith, as quoted in D. Michael Quinn, “The Culture of Violence in Joseph Smith’s Mormonism.”

8 Quinn, “The Culture of Violence in Joseph Smith’s Mormonism.”

9 There are numerous scholarly works that address aspects of this early American culture of violence such as Richard Maxwell Brown’s pathbreaking Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975). For examples of women and violence, see Craig L. Foster, “The Wrath of a Wronged Woman: Ways Nineteenth Century Women Punished Wrongdoers,” Wild West History Association Journal 14:4 (December 2021): 44-60.

10 Suzanne Marshall, Violence in the Black Patch of Kentucky and Tennessee (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994), 43.

11 John D. Carlson and Jonathan H. Ebel, “Introduction, John Brown, Jeremiad, and Jihad: Reflections on Religion, Violence, and America,” in John D. Carlson and Jonathan H. Ebel, Eds., From Jeremiad to Jihad: Reflections on Religion, Violence, and America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 8.

12 Marshall, 43 and 41. Marshall also notes on page 42 regarding actions toward real and perceived sinners, “Harsh penalties, modeled on punishments of an angry God, were meted to violators of community standards. Elite and middle-class whites saw no contradiction in enforcing morals with violence.”

13 Charles Wellborn, “Brann vs the Baptist: Violence in Southern Religion,” Christian Ethics Today, issue 33, December 2010, https://christianethicstoday.com/wp/brann-vs-the-baptist-violence-in-southern-religion/, accessed June 18, 2024.

14 Michael Simoncelli, “Ruffians and Revivalists: Manliness, Violence, and Religion in the Backcountry South, 1790- 1840,” (1999), Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects, William and Mary, 36.

15 Morgan County Democrat (Versailles, Missouri), December 18, 1903, 4.

16 Matthew J. Hernando, Faces Like Devils: The Bald Knobber Vigilantes in the Ozarks (Columbus, Missouri: The University of Missouri Press, 2015), As quoted in Craig L. Foster, “Was the ‘Mormon Culture of Violence’ Really the Only Top-Down Violence in 19th Century America?” [Unpublished presentation from John Whitmer Historical Association 2015 conference, Independence, Missouri].

17 Michael J. Pfeifer, “Law, Society, and Violence in the Antebellum Midwest: the 1857 Eastern Iowa Vigilante Movement,” The Annals of Iowa 64:2 (Spring 2005), 157 and Barbara Marriott, Outlaw Tales of New Mexico: True Stories of New Mexico’s Most Famous Robbers, Rustlers and Bandits (Guilford, CT: TwoDot, 2007), 69.

18 Kimberly R. Kellison, “Parameters of Promiscuity: Sexuality, violence, and religion in Upcountry South Carolina,” in Edward J. Blum and W. Scott Poole, eds., Vale of Tears: New Essays on Religion and Reconstruction (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 2005), 24.

19 Kelly J. Baker, Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2011), 10 and Kellison, “Parameters of Promiscuity,” 22. Baker notes on page 9 of Gospel According to the Klan, “Klansmen were more evangelical than fundamentalist.”

20 Ibid., 11 and 9.

21 Simoncelli, 30 and 36.

22 “Preacher Leads the Mob,” Emproria Gazette, March 4, 1898, 1.

23 “Crimes and Casualties: A Pleasant Preacher,” The San Francisco Examiner, May 31 1883, 1. 24 “A Minister Whipped,” The Buffalo News, July 16, 1888, 4.

25“Disgraceful Proceedings Among Northern Preachers,” Charlotte Home and Democrat, July 6, 1883), 2.

26 “Rival Preachers,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 25, 1883, 7.

27 Walter L. Buegner, “Making Sense of Texas and its History,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 121:1 (July 2017), 7. According to Paul Harvey, Redeeming the South: Religious Cultures and Racial Identities among Southern Baptists (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 42, “During Reconstruction, white southern Baptists prepared for a cultural and political war to defend white supremacy. If violence was necessary to this end, they were prepared to use it.” Another example of Baptist violence actually involves violence between fellow Baptists. In 1898, Franklin College, a Baptist college in Franklin, Indiana witnessed a large fight turn into a bloody riot between Seniors and Sophomores on one side and Juniors and Freshman on the other side. Over one hundred students were involved and “Heads were broken, faces cut and blood flowed freely.” “Baptist Students Fight,” Boston Daily Advertiser, January 19, 1898, 2.

28“A Clerical Ku Klux,” Harrisburg Telegraph, January 2, 1873.

29 Ibid.

30 Marshall, 136.

31 John Nova Lomax, “The Apostle of the Devil,” Texas Monthly, June 3, 2016, https://www.texasmonthly.com/the daily-post/the-apostle-of-the-devil/, accessed 17 June 2024.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid and “Rough on Brann,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), October 3, 1897, 2 and “Students Mob an Editor,” New York Tribune, October 4, 1897, 1.

34 Lomax, “The Apostle of the Devil.”

35 Ibid.

36 “Cowhided in His Pulpit,” Martinsburg Herald, September 24, 1892, 1 and Baxter Springs News (Kansas), October 1, 1892, 1.

37 “Pitch Fight at the Dutch Church in Forsyth Street,” The New York Herald (6 SEP 1842), 2. 38“Row in a Church—A Rich Scene,” The Weekly Hawk-Eye (Burlington, Iowa), January 11, 1859, 1. 39 Aaron Spencer Fogleman – Jesus Is Female: Moravians and Radical Religion in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 215 and 205.

40 Stephen H. Cutcliffe and Karen Z. Huetter, “Religious Conflict and Violence in German Communities during the Great Awakening,” in Jean R. Soderlund and Catherine S. Parzynski, eds., Backcountry crucibles : the Lehigh Valley from settlement to steel (Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Lehigh University Press, 2008), 191. 41 Craig D. Atwood, “’The Hallensians are Pietists; aren’t you a Hallensian?’ Mühlenberg’s Conflict with the Moravians in America,” Journal of Moravian History 12 (2012), 47.

42“True Religion,” Morning Herald (New York City), August 3, 1837, 2.

43“Riot in Chillicothe,” The Portsmouth Inquirer, January 13, 1851, 2 and The Portsmouth Inquirer, January 20, 1851, 2.

44 Richard Carwardine, “Methodists, Politics, and the Coming of the American Civil War,” Church History 69:3 (September 2000), 593, 604-05.

45 Dickson D, Bruce, Jr., Violence and Culture in the Antebellum South (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979), 113.

46 Douglas Montagna, “’Choked Him Til His Tongue Protruded’: Violence, the Code of Honor, and Methodist Clergy in the Antebellum Ohio Valley,” Ohio Valley History 7, no. 4 (Winter 2007): 16.

47 Ibid., 27-28.

48 Richard Carwardine, “Methodists, Politics, and the Coming of the American Civil War,” Church History 69, no. 3 (September 2000): 593.

49 Montagna, 28-29.

50 “Mob Law in Texas—A Methodist Conference Broken Up and Dispersed,” Providence Evening Press, April 26, 1859, 2.

51 . “Where Actors Are Not Wanted,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer (26 September 1884), 1 and Buffalo Courier Express, November 1, 1889, 1.

52 “Cowhiding a Bigot,” The Corinne Daily Reporter, May 6, 1873, 2.

53 “A Shooting Preacher,” Alexandria Gazette, November 21, 1891, 2.

54 “A Shooting Preacher,” Joplin Weekly Herald, March 6, 1892, 4.

55 Grey River Argus (Greymouth, New Zealand), July 28, 1883, 2.

56“Presbyterians and the American Revolution: Before: Religious and Political Conflict in the 1760s,” Presbyterian Historical Society, https://www.history.pcusa.org/history-online/exhibits/religious-and-political-conflict-1760s page-3, accessed July 12, 2024 and John Smolenski, “Murder on the Margins: The Paxton Massacre and the Remaking of Sovereignty in Colonial Pennsylvania,” Journal of Early Modern History 19 (2015), 513.

57 Paul Scott Gordon, “The Paxton Boys and the Moravians: Terror and Faith in the Pennsylvania Backcountry,” Journal of Moravian History 14 (2014), 119.

58 Kellison in Vale of Tears, 23.

59“Killed a Shooting Preacher,” The Sun (New York City), June 27 1895, 1.

60 Janet Moore Lindman, “’Deluded Women’ and ‘Violent Men:’ Women, Gender and Language in the Hicksite Schism,” Quaker History 109:1 (Spring 2020) and Harry Kyriakodis, “Rowdy Meetinghouse On Green Street Divides Quakers,” Hidden City: Exploring Philadelphia’s Urban Landscape, May 8, 2015,

https://hiddencityphila.org/2015/05/rowdy-meetinghouse-on-green-street-divides-quakers/, accessed July 17, 2024.

61 Kenneth C. Barnes, Anti-Catholicism in Arkansas: How Politicians, the Press, the Klan, and Religious Leaders Imagined an Enemy, 1910-1960 (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2016), 4.

62 Richard Maxwell Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 28 and David Grimstead, American Mobbing, 1828-1861: Toward Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 233.

63 Kara M. French, “Prejudice for Profit: Escaped Nun Stories and American Catholic Print Culture,” Journal of the Early Republic 39 (Fall 2019), 504.

64“Highly Important from N. York,” State Indiana Sentinel (Indianapolis), November 9, 1841, 3 and “Riots and Bloodshed,” State Indiana Sentinel (Indianapolis), November 9, 1841, 3.

65 Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 336, fn 125.

66 Amanda Beyer-Purvis, “The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844: Contest Over the Rights of Citizens,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic History 83:3 (Summer 2016), 366.

67 “City of Brotherly Love: Violence in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia,” Exploring Diversity in Pennsylvania History, www.hsporg, accessed June 18, 2024.

68“An ‘Angel Gabriel’ Mob—Riot and Outrage—A Catholic Church Burned, etc.” Richmond Daily Wig, July 10, 1854, 3.

69 Cary Hutto, “In August 1842, riots broke out in Philadelphia and threatened the home of Robert Purvis. What were they called?” Historical Society of Pennsylvania, July 29, 2014, https://hsp.org/blogs/question-of-the-week/in august-1842-riots-broke-out-in-philadelphia-and-threatened-the-home-of-robert-purvis-what-were-th, accessed July 17, 2024. Much like their Baptist and other Protestant counterparts, Catholics could also fight among themselves. According to “Warring Religious Factions,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, October 23, 1889, a fight broke out between two Catholic congregations for the possession of a church in Plymouth, Pennsylvania. The fight was so fierce that people, including police, were injured.

70“Damages for Mob Violence,” Burlington Free Press (Burlington, Vermont), April 7, 1843, 2.

71“The Mob Spirit—Religious Intolerance,” National Era, Washington DC, March 11, 1852, 42.

72 The True Northerner (Paw Paw, Michigan), March 31, 1871, 5.

73“Riots in Quebec,” Boston Journal, August 8, 1894, 3 and “Disgraceful Riot,” Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), August 8, 1894, 1.

74“Ex-Priest Slattery,” The Wichita Daily Eagle, October 28, 1893, 1. According to Jonathan Smyth, “The Slatterys: An ex-priest and a ‘bogus’ nun,” The Anglo-Celt, September 12, 2021, https://www.anglocelt.ie/2021/09/12/the slatterys-an-ex-priest-and-a-bogus-nun/, accessed July 17, 2024, Joseph Slattery appears to have studied to be a

Catholic priest before becoming a Protestant. Mary Elizabeth, however, was never a nun nor did she appear to have been from Cootehill, Cavan, Ireland as she claimed. Their story and claims were a fabrication.

75“An Angry Mob,” The Herald (Los Angeles, California), April 5, 1894, 3 and “Wanted to Lynch Him,” The Indianapolis Journal, April 6, 1894, 1.

76“Religious Rioters,” Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, February 27, 1895, 1; “Religious Riots,” The Plain Dealer, February 27, 1895, 1; “Wild religious Riot,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 27, 1895, 1; and “Ex-Priest Slattery Again,” The Herald (Los Angeles), February 26, 1895, 1. Based on newspaper stories, the couple continued their lecture tour for some time after that night.

77 D. Michael Quinn, “National Culture, Personality, and Theocracy in the Early Mormon Culture of Violence,” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 2002 Nauvoo Conference Special Edition (2002), 159. Quinn correctly notes the how American culture very early on redefined the duty to avoid violence as had been defined in English common law. This duty to avoid violence had been referred to as the “duty to retreat.” In America on the other hand, there was “no duty to retreat.” Quoting Richard Maxwell Brown, No Duty to Retreat: Violence and Values in American History and Society (New York City: Oxford University Press, 1991), 4-5, that in Britain’s centuries-old “society of civility, for obedience to the duty to retreat—really a duty to flee from the scene altogether or, failing that, to retreat to the wall at one’s back—meant that in the vast majority of disputes no fatal outcome would occur.” In early Republic United States courts and culture, however, “the nation as a whole repudiated the English common-law tradition in favor of the American theme of no duty to retreat: that one was legally justified in standing one’s ground to kill in self-defense.” The American tradition of no duty to retreat, also known as stand your ground, is still in law books of a number of U.S. states.

78 Craig L. Foster, “Death to Seducers! Examples of Latter-day Saint-led Extralegal Justice in Historical Context,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020), 281.

79 Quinn, “The Culture of Violence in Joseph Smith’s Mormonism.”

80 For excellent information and understanding regarding the Mountain Meadows Massacre, see Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Glen M. Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows (New York City: Oxford University Press, 2011) and Richard E. Turley and Barbara Jones Brown, Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath (New York City: Oxford University Press, 2023).

81 Brown, Strain of Violence, 4 and 7.

82 Kathy Alexander, “The Real Virginia City & Vigilante History (Unfiltered),” Virginia City Silent Riders, https://silentriders.org/history, accessed July 18, 2024.

83 Ibid.

84 Elmer D. McInnes with Lauretta Ritchie-McInnes, Nevada Gunsmoke: Frontier Fighters of the Boom Years, 1850- 1890 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2022), 195 and 129.

85 Brown, Strain of Violence, 101.

86 John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 262. The number of violent incidents in Utah appears to have been less than in most surrounding states and territories. For example, cases of lynching between 1882 and 1903 are as follows: Arizona had 28, California 41, Colorado 64, Idaho 19, Montana an incredibly high 85, New Mexico 34, Oregon 19, Washington 26, and Wyoming 37. Of the states and territories surrounding Utah, only Nevada, with 5, had less than Utah’s 7 recorded cases of lynching. These numbers and information are from Walter White, Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch (New York: Knopf, 1929; repr. New York: Arno, 1969), 254–59 and Frank Shay, Judge Lynch: His First Hundred Years (New York: Biblo and Tannen, 1969), 141, 144–47, 150, as quoted in Craig L. Foster, “Myth vs. Reality in the Burt Murder and Harvey Lynching,” Journal of the West 43/4 (Fall 2004): 54.

87 David T. Cartwright, Violent Land: Single Men and Social Disorder from the Frontier to the Inner City (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), 1.

88 Eric A. Eliason, “Review of: Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847– 1896,” FARMS Review of Books 12/1 (2000): 95–112, as quoted in “Did Utah foster a culture of violence in the 19th century?” FAIR Latter-day Saints,

https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/answers/Utah/Crime_and_violence/Culture#cite_note-1, accessed June 18, 2024.

89 Thomas K Scott, “Violence across the Land: Vigilantism and Extralegal Justice in Utah Territory” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 2010), 117. For examples of extralegal justice in Utah see Kenneth L. Cannon II, “‘Mountain Common Law’: The Extralegal Punishment of Seducers in Early Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 51 (Fall 1983), 308–27; Craig L. Foster, “The Butler Murder of April 1869: A Look at Extralegal Punishment in Utah,” Mormon Historical Studies 2 no.2 (Fall 2001), 105–14; and Craig L Foster, “Death to Seducers! Examples of Latter-day Saint-led Extralegal Justice in Historical Context,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 281-306.

90 Ibid., 56.

91 William Chandless, A Visit to Salt Lake; Being a Journey Across the Plains and a Residence in the Mormon Settlements at Utah (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1857), 181, as quoted and discussed in Thomas K Scott, “Violence across the Land,” 56. William Chandless also wrote that the constant “’fear of being attacked with violence, or outnumbered by settlers,’ impelled early Utah Mormons to a disloyalty rooted in ‘fear’ rather than genuine ‘dislike or savage temper.’ They could be loyal, if given the space and chance.” Chandless, A Visit to Salt Lake, 183.

92 Brigham Young, February 8, 1857, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: 1862), 4:219-220.

93 Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation of 1856-1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality,” Journal of Mormon History 15, no. 1 (1989), 84 n. 69 and Ronald W. Walker, “Raining Pitchforks: Brigham Young as Preacher,” Sunstone 8 (May/June 1983), 7. Walker’s article, page 5-9 of that issue of Sunstone is excellent for better understanding Brigham Young’s style and purpose of preaching and helps put the Mormon Reformation and teachings of blood atonement in historical context.

94 Ronald W. Walker and Ronald K. Esplin, “Brigham Himself: An Autobiographical Recollection,” Journal of Mormon History, 4 (1977): 27-28.

95 Scott, “Violence across the Land,” 110.

96 Isaac Haight, “Isaac C. Haight letter,” October 29, 1856, CR 1234 1, Church History Library; Brigham Young, letter to Isaac C. Haight, March 5, 1857, in Brigham Young office files transcriptions, 1974-1978; Letterbooks; Letterbook Volume 3, 1857 February 19-April 1, 461-2; Church History Library as cited in “Blood Atonement and Capital Punishment,” Mormonr,

https://mormonr.org/qnas/0vsOHr/blood_atonement_and_capital_punishment/research#re-5znjCc-svNVeb, accessed July 19, 2-24.

97 Scott, “Violence Across the Land,” 112 and 105.

98 Ibid., 105.

99 Ibid, 118. In this quote, Scott is referring to the quote from Wallace Stegner, Mormon Country (1942; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1970), 96.

100 Thomas G. Alexander, “Review of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows,” Brigham Young University Studies 31:1 (January 2003), 167 as quoted in “Did Utah foster a culture of violence in the 19th century?” Fairlatterdaysaints.org,

https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/answers/Utah/Crime_and_violence/Culture, accessed 14 June 2024.

101 Patrick Q. Mason, “’The Wars and the Perplexities of the Nations’: Reflections on Early Mormonism, Violence, and the State,” Journal of Mormon History 38 (Summer 2012), 74. Mason quotes R. Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 19.

102 Mason, “The Wars and the Perplexities,” 74. Mason also asserts that “believers from all traditions, including Mormonism, have all too often committed mass violence and atrocities and have sanctioned other forms of deeply embedded structural and cultural violence…”(74).

coming soon…

- Date Presented: October 12, 2024

- Duration: 43 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Virtual Conference, “Understanding and Defending the History of the Church”

- Topics Covered: Mormon culture of violence, Mormon history, Latter-day Saint violence, Mountain Meadows Massacre, blood atonement, extralegal justice, vigilante justice in Utah, 19th-century American violence, early American religious violence, Brigham Young teachings, Joseph Smith controversies, anti-Mormon violence, religious persecution in America, Christian denominations and violence, Baptist violence, Methodist violence, Presbyterian violence, Catholic violence, vigilante groups in the West, American frontier violence, American Primeval Netflix, American Primeval historical accuracy, portrayal of Mormons in media, Under the Banner of Heaven critique, LDS Church and violence, Mormonism and society, 1800s vigilante movements, American West lawlessness, Craig Foster FAIR presentation, Mormon theology misconceptions, Krakauer and Mormonism, anti-Catholic riots, Protestant violence, historical religious conflict, American Primeval Mormon portrayal, Mormon myths, misunderstood Mormon doctrines, FAIR Mormon apologetics.

Was Mormon Utah uniquely violent compared to other territories?

The presentation demonstrates that violence in Utah was significantly lower than in surrounding territories, and vigilante justice was far less prevalent in Utah than in other western states like Montana and Texas.

Did Brigham Young and early Church leaders promote violence through blood atonement?

While Brigham Young used fiery rhetoric about blood atonement, historians agree that it was largely a rhetorical device meant to encourage repentance, and actual instances of blood atonement killings are extremely rare and difficult to substantiate.

How does Mormon violence compare to violence in other Christian denominations?

By citing numerous examples of violence among Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Catholics, and others, the presentation places Mormon violence in the broader context of 19th-century American religious violence, showing that such behavior was not unique to Latter-day Saints.

Why is Mormonism often portrayed as violent in media, such as in Under the Banner of Heaven and America Primeval?

The presentation suggests that portraying early Mormon leaders as violent radicals undermines the credibility of their religious message. Media depictions often take events out of historical and social context to create sensational narratives.

Were non-Mormons unsafe in Utah during the 19th century?

Contrary to common claims, historical evidence shows that Utah was generally tolerant toward non-Mormons, and most visitors and settlers experienced little to no violence.

Did vigilante justice in Utah reflect Mormon teachings?

Vigilante justice in Utah was not driven by Mormon theology but was instead a reflection of broader frontier culture, where communities often resorted to extralegal methods due to the absence of formal law enforcement.

Is violence an inherent part of religious groups, including Latter-day Saints?

The presentation underscores that all religious traditions have conflicting elements that can lead some adherents toward violence while others seek peaceful solutions. This pattern is seen across various denominations, not just among Mormons.

Does the Mountain Meadows Massacre indicate a broader pattern of Mormon violence?

The massacre was a tragic and complex event influenced by extraordinary circumstances, but it remains an anomaly in Mormon history rather than evidence of a pervasive culture of violence.

Were early American societies generally violent?

The presentation emphasizes that 18th and 19th-century America was broadly characterized by a culture of violence, where physical confrontations and extralegal justice were often expected responses to conflict.

*See the Fact check on American Primeval, which draws on this talk in part.

The primary apologetic focus of Craig Foster’s paper is to contextualize violence attributed to early Latter-day Saints within the broader historical, cultural, and religious landscape of 19th-century America. By doing so, it defends the LDS Church against claims that it was uniquely violent or exceptionally prone to extralegal justice. Here’s a breakdown of the key apologetic foci:

1. Contextualizing Mormon Violence within 19th-Century Religious Norms

- Criticism Addressed:

Critics often portray early Mormons as unusually violent or prone to radical behavior, using events like the Mountain Meadows Massacre and blood atonement rhetoric to support their claims. - Apologetic Response:

Foster demonstrates that violence was not unique to Mormonism but was widespread among various Christian denominations, including Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Catholics. This broader perspective shows that Mormon violence was part of a larger cultural pattern, not a distinctive characteristic of the LDS Church.

2. Clarifying the Nature of Blood Atonement

- Criticism Addressed:

The concept of blood atonement is frequently misunderstood and used by critics to portray early Mormon leaders, especially Brigham Young, as advocating for religiously sanctioned killings. - Apologetic Response:

Foster highlights that blood atonement rhetoric was a figurative, rhetorical device intended to emphasize the seriousness of sin and encourage repentance. He cites historians who assert that actual instances of blood atonement killings were extremely rare and often anecdotal or unsubstantiated.

3. Addressing Media Misrepresentations of Mormon History

- Criticism Addressed:

Modern media, such as Under the Banner of Heaven and America Primeval, often sensationalize Mormon history, portraying early Latter-day Saints as religious fanatics prone to violence. - Apologetic Response:

Foster critiques these portrayals, arguing that they remove events from their historical and social context to fit a biased narrative. He emphasizes that such depictions mislead audiences by focusing on isolated incidents while ignoring the overall peaceful nature of early Mormon communities.

4. Defending the Reputation of Early Mormon Leaders

- Criticism Addressed:

Critics frequently attack the personal character of early Mormon leaders like Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, depicting them as violent or authoritarian figures. - Apologetic Response:

Foster defends these leaders by providing historical context, showing that their actions and rhetoric were in line with the norms of their time. He points out that while their rhetoric could be harsh, it was typical of 19th-century preaching styles and should not be judged by modern standards.

5. Debunking the Myth of a Uniquely Violent Mormon Utah

- Criticism Addressed:

Critics claim that Utah under Mormon leadership was exceptionally violent or lawless. - Apologetic Response:

Foster presents evidence showing that, compared to surrounding territories like Montana and Texas, Utah had significantly less vigilante activity and extralegal violence. He cites scholars who note that Utah was one of the least violent jurisdictions in the western United States during the 19th century.

Conclusion: A Balanced Historical Perspective

The apologetic focus of this paper is to provide a balanced, evidence-based historical perspective that refutes exaggerated claims about Mormon violence. By placing Latter-day Saint history alongside that of other religious groups and western communities, Foster shows that early Mormon violence was neither exceptional nor indicative of the faith’s core teachings. Instead, it reflects the common challenges faced by all frontier societies during that era.

Share this article