Presentation by Jeffrey Thayne

Transcript

[Jeffrey Thayne]

What Do We Treasure

What do we treasure? The answer to this question changes everything else. Imagine an archaeologist and a treasure hunter who stumble upon the same ancient treasures. The archaeologist sees a site to carefully excavate for knowledge and artifacts that illuminate history. The treasure hunter sees only sparkling gems and gold to quickly loot and profit from. They see something fundamentally different.

What we see Depends on What we Seek

President Oaks explained, “What we see around us depends on what we seek in life.”

At their core, worldviews are value systems. There is no such thing as a view of the world that is not filtered through our values. Our core values—our greatest treasure—change our vantage point.

Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf taught: “For what we love determines what we seek. What we seek determines what we think and do. What we think and do determines who we are—and who we will become.” When we value most what God values most, we are in the best vantage point to see and measure our lives the way God sees and measures our lives.

Four worldviews

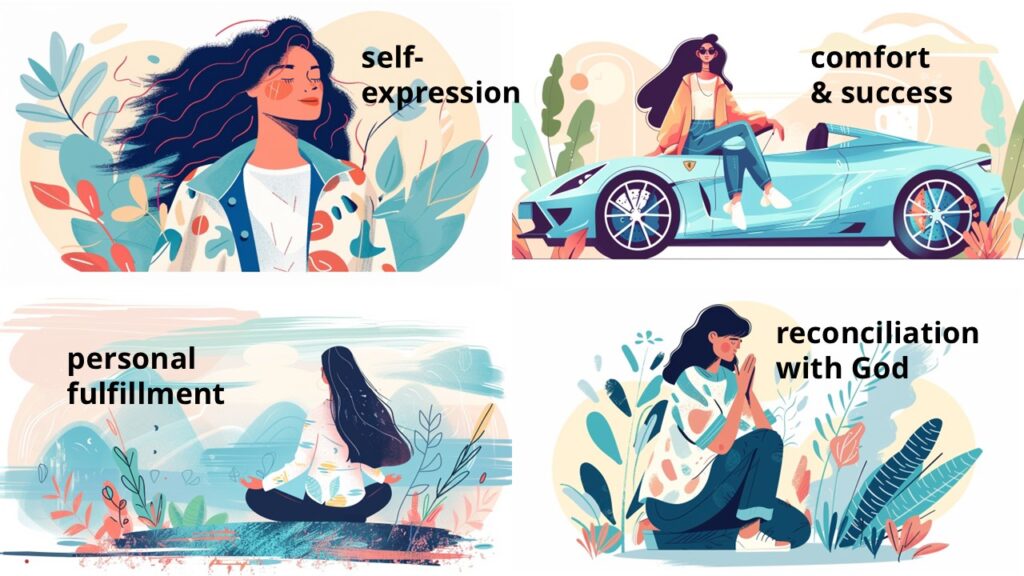

Let’s explore four different worldviews. I am going to describe each of these as a “gospel.” This is because each worldview defines human flourishing or the “good life” a bit differently, and thus what we think of as the end or goal of living the gospel. The term gospel means “good news.” What we desire most determines what constitutes good news to us. What do we treat as good news?

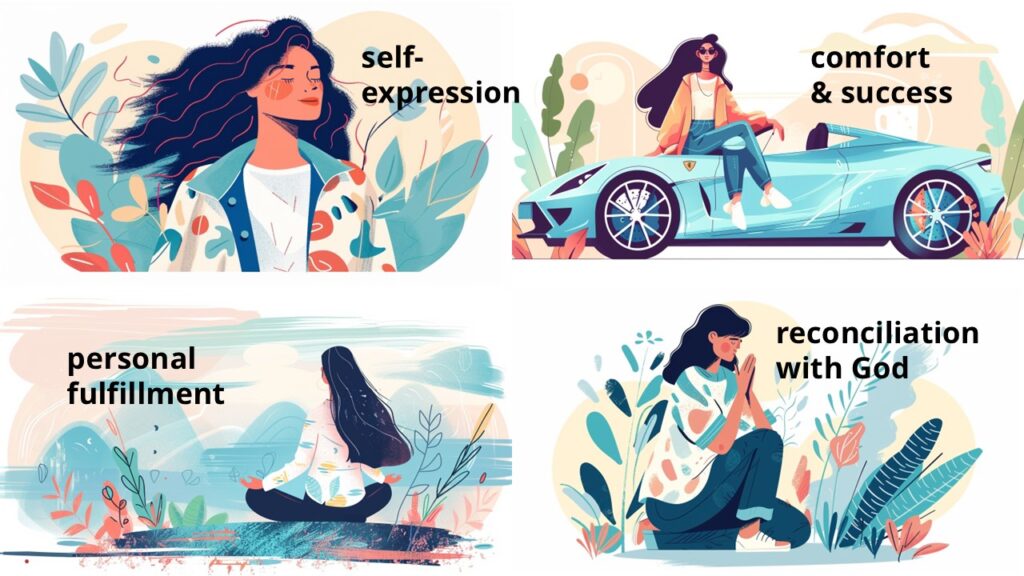

The Expressive Gospel

The expressive gospel treats self-expression and personal authenticity as our core values, the highest prize towards which we strive. When we embrace the expressive gospel, we emphasize the importance of being ourselves rather than being pushed into molds and social templates. We want to be accepted by others for who we are, to be able to live out our unique priorities, desires, and eccentricities. We wrap our self-concept around what makes us different.

Now all other features of a worldview fall into place. What stands in the way? If our chief goal is to “be ourselves,” then any community norm that prescribes a certain life path or set of behaviors becomes a stumbling block. In the expressive gospel, the rebels of the community are often the protagonists, and the villains are those who reinforce community norms. Non-conformity is the key to the good life, which is achieved by becoming your true self, and when the community celebrates you for who you are.

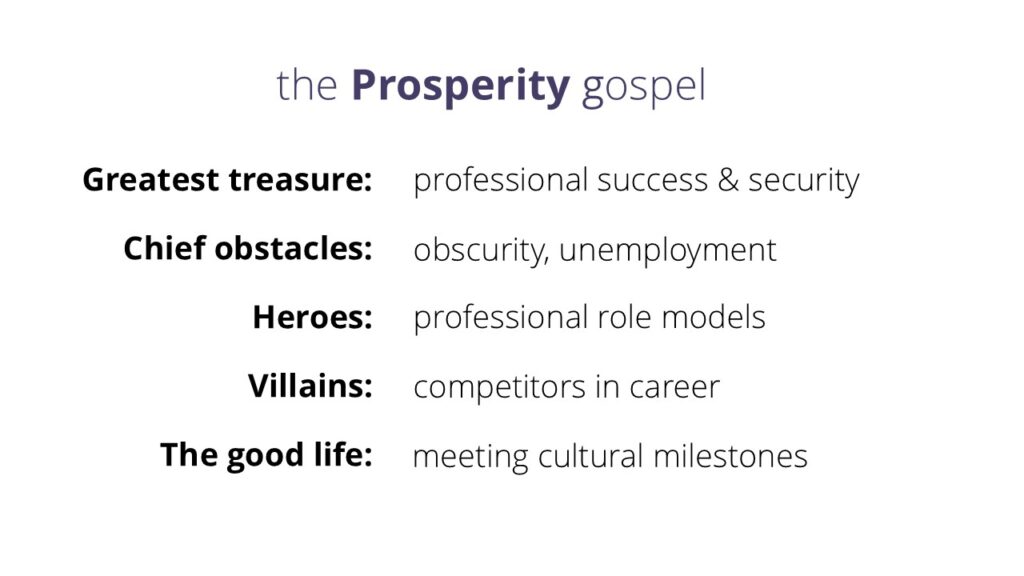

The Prosperity Gospel

The prosperity gospel comes in a variety of flavors. Within this worldview, sometimes the good life is found in comfortable living and material possessions—living a middle class lifestyle (or above), plenty of leisure time, and freedom from unwanted responsibilities. Other times the good life is found in professional success.

The conflict of the story then centers on our struggle to be noticed and the threat of obscurity. As an aspiring musician, will I get noticed by the top record labels? As an aspiring athlete, will I get drafted into the big leagues? As an aspiring writer, will one of my books become a bestseller? Latter-day Saints sometimes put their own spin on the prosperity gospel. We treat life benchmarks and milestones from our religious

tradition—such as serving a mission, getting married, having children, and serving in Church callings of escalating importance—as measures of success in living the Gospel. We might talk about how paying tithing insulates us from financial hardship, or how living the Word of Wisdom grants us health and longevity.

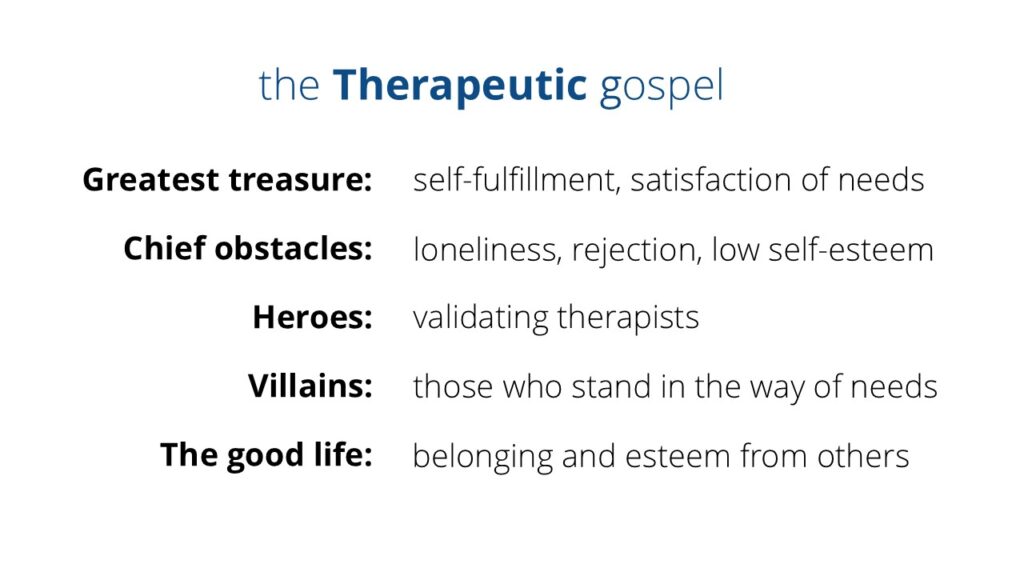

The Therapeutic Gospel

The therapeutic gospel treats personal fulfillment and the satisfaction of personal needs as our greatest treasure. Abraham Maslow believed that human suffering stems largely from unmet personal needs. Maslow believed that our needs could be organized loosely into a hierarchy, with basic needs (such as food and water) at the bottom, safety needs next (such as freedom from physical and social aggression), followed by the needs for love and belonging (this includes a place to call home and intimate companionship), and finally by our need for esteem (which includes the need to feel important in and valued by our community).

The therapeutic gospel offers us a vision of what is wrong with us and the world: we face emotional deficiencies and the traumas of rejection, loneliness, and insecurity. We become emotionally malnourished for lack of emotional safety, esteem, physical intimacy, and community connection. The protagonist of the story seeks personal fulfillment—that is, the fulfillment of personal needs. The term “fulfillment”—used in this way—grew in popularity as Maslow’s ideas filtered into our culture.

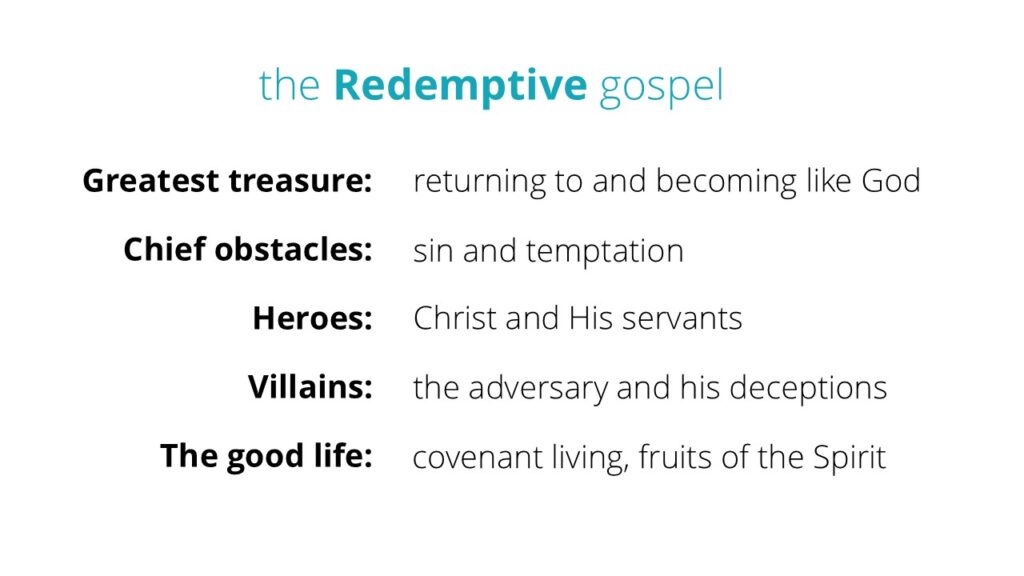

The Redemptive Gospel

And lastly, the redemptive gospel treats reconciling with God as our greatest treasure. In this worldview, our greatest desire is to return to live with God, and to eventually become like Him in character and virtue—to enjoy that divine presence, and to take on those divine characteristics and Christlike virtues. The gift of the Holy Ghost represents God’s presence in our life (reconciliation), and the fruits and gifts of the Spirit represent His redemptive work in our hearts (transformation).

In this story, what stands in the way? We have all been alienated from God through pride, enmity, weakness, or rebellion. The more we aspire to the presence and divine nature of God, the more we recognize the chasm that separates us from Him, which we cannot cross ourselves. And so we seek reconciliation with God through the merits and grace of Christ. We take upon ourselves the name of Christ by making and keeping covenants with God and participating in sacred ordinances.

Plot-driven or Character-driven Stories

We have here four different worldviews. The question is, which of these values do we elevate as our greatest treasure? Which floats to the top of our stack of priorities? In other words, which of these are subplots in our life story, and which are the main plot? Each core value shapes every other aspect of the story — including what we consider to be the obstacles in our way, our greatest disappointments, the heroes and villains of our story, and how we define human flourishing and the good life — that is, the happy ending of our story.

So why is this all important? Let me illustrate with an example. Someone I know has faced a devastating illness that has kept her from serving a mission, graduating from college, marrying, or pursuing a career. All of her various life subplots have been interrupted for two decades now. Some months, her benchmarks for daily success involve getting out of bed, making breakfast, and tidying her room. Many days, even that is difficult. One day, in a moment of depression, she asked me, “Why is the Gospel not working for me?”

Note what the question presumes as the purpose of Gospel living. Let me share another example. A dear friend of mine sacrificed for several years to finish a doctorate degree, while raising several children and serving in the Church. Weeks after he finished his degree, he was diagnosed with colon cancer, and two years later he passed away. Did the Gospel fail him? Well, it depends on what we see as the purpose of the Gospel — which depends on our worldview (or what we see as our greatest treasure).

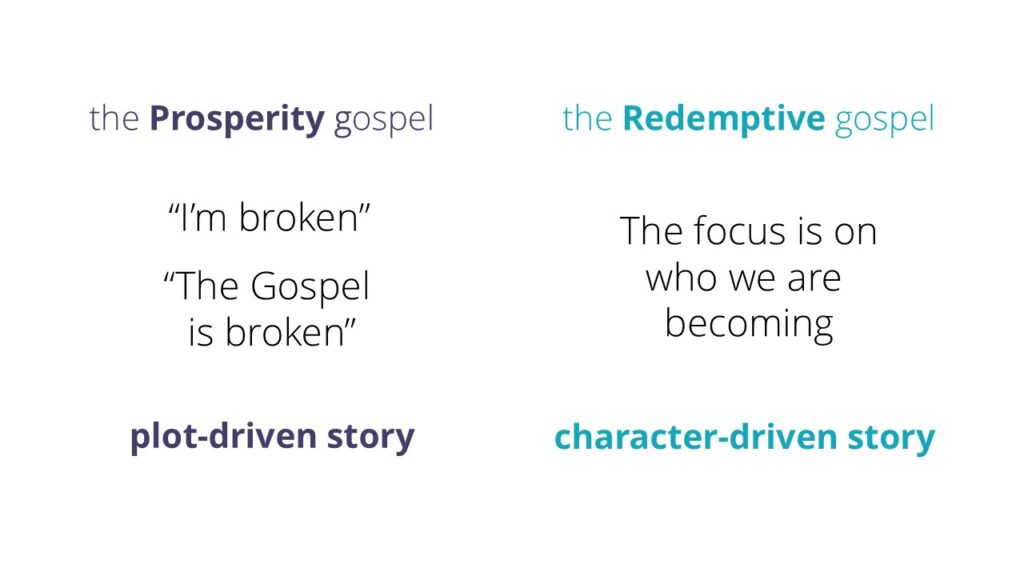

If we embrace the prosperity gospel, when circumstance turns against us, we might conclude that we are broken in some way—that our best efforts at living Gospel just aren’t good enough. Or we might treat it as a failure external to us, and conclude, “The Gospel of Jesus Christ isn’t working for me.” When we wonder if the Gospel has failed us because we have missed milestones such as graduation, mission, employment, marriage, children, or retirement, we might have supplanted the Gospel story with a prosperity-based counterfeit.

In contrast, the redemptive Gospel of Jesus Christ, our greatest priority is reconciling with God—overcoming the fall. This involves moral transformation in the image of Christ, becoming new creatures in Christ. Unlike the plot-driven story of the prosperity Gospel, the redemptive Gospel is a character-driven story. The focus is not on events that happen to us, but on who we become in the process. We succeed in Gospel living as our character changes through repentance, covenant-keeping, and receiving the fruits and gifts of the Spirit.

When my loved one asked, “Why is the Gospel not working for me?”, my response was and still is, “You are more Christ-like because of the way you have endured hardships—faithfully keeping your covenants and seeking the fruits of the Spirit. The Gospel is working for you.” If I could convince her of one thing, it is that her success in life is not contingent on how brightly she shines in her professional pursuits, or even whether she can do anything more than get dressed on any given day (if that is all she can do). It is measured by the kind of person she is becoming.

The Gospel, understood this way, works for everyone. The same-sex attracted. Those with chronic illness. The unemployed. The infertile. Those who are grieving. Those who feel their talents are underutilized. All can enjoy the gifts of the Spirit and become sanctified (holy) as people. When the redemptive worldview is the main plot of our lives, life’s various subplots can be interrupted and the main story can still be reconciliation with God through Christ and feasting on the fruits and gifts of the Spirit. This character-driven story is never derailed by the vicissitudes of life.

When my friend — the one who had just received his doctorate — was sick with colon cancer, I visited him a few times over the next two years. If he had used a prosperity template for the main plot of his life’s story (which he did not), subsequent events would have been like losing the wi-fi halfway through the movie, interrupting the story and leaving a lot of vitally important loose ends. All sorts of circumstances can derail the prosperity gospel, which makes it a fickle master, quick to disappoint us.

But when I visited with him, his countenance radiated light and truth. His story of redemption was not interrupted in the slightest by his illness. This does not minimize or trivialize the disappointments and griefs of a life cut tragically short. All his other stories were interrupted, and that comes with untold grief no matter our core values. But the main plot — the redemptive story — was not interrupted. In his final months, I can say with confidence that he was sanctified through the grace of Christ and transformed in the image of God Himself. None of life’s circumstances can derail the redemptive gospel.

Subtle Gospel Counterfeits

Let’s go back to the four worldviews. When any of these other values — self-expression, material comfort, professional success, cultural milestones, self-fulfillment, and so on — become the main plot of our life story, we can encounter what I sometimes refer to as gospel counterfeits. The term counterfeit carries a strongly negative connotation. We see counterfeiters as malicious lawbreakers. In this context, however, I use the term in a more descriptive way. A counterfeit is simply something that is superficially similar to the real thing—similar enough to be mistaken for it—but crucially different underneath.

In each case, the performances of faith may be superficially similar. For example, those who embrace each of these worldviews might pray and seek God’s involvement in their lives, but for fundamentally different reasons. Do we seek God’s involvement in our lives primarily so that we can be and feel accepted for who we are (the expressive Gospel)?

Or so that we can overcome vice and become transformed in Christ’s image (the redemptive gospel)?

Some have left the faith because they have felt let down by a gospel that was never the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Put in a different way, some never leave the Gospel of Jesus Christ because they were never converted to it in the first place.

Rather, they were converted to a very subtle distortion or counterfeit of it—versions of the prosperity gospel or the therapeutic gospel wearing the garb and speaking the language of the redemptive Gospel. And when these subtle counterfeits disappoint them, as all counterfeits eventually do, they assume they were disappointed by the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Getting this right is about far, far more than merely providing comfort to those whose lives deviate from the cultural template or who miss various milestones in life. Those who follow the template can miss the entire purpose of the Gospel of Jesus Christ when they treat these plot points as the main story.

A stake president once shared with me:

I know plenty of couples who did the “right” things that got them to a temple marriage, but who left the Church (frequently as couples) because they didn’t actually have a connection to Christ and His Gospel that would help them continue to change and evolve to become like God. They viewed temple marriage as the end-all-be-all of what we’re trying to do. But it’s ultimately becoming like Christ that is the purpose.

He continued, “Becoming like Him will lead to desires for Celestial marriage and eventually to it,” but he lamented how many couples he has counseled who saw the event of marriage as the goal, and who thus stopped pursuing transformation through Christ, even as their characters rotted through that spiritual neglect.

Shifts in the Light

Let’s return to what President Oaks said: “What we see around us depends on what we seek in life.” In other words, our worldview—our core values—change how the world looks to us, in ways that can either strengthen or undermine our faith and conviction. Picture how a bend in the lens might shift some wavelengths, such as how some colors show up differently as you look at them through the edge of your eyeglasses. President Oaks further explained, “Each of us has a personal lens through which we view the world. Our lens gives its special tint to all we see. It can suppress some features and emphasize others.”

For example, what does love look like to us? How we feel God’s love — and how we feel the love of others — depends on what we hold as our greatest treasure. If we see personal authenticity and self-expression as our greatest value, then love is going to look a whole lot like celebrating me for who I am. I am going to feel loved when—and only when—I feel that others accept me and my choices. I am going to feel unloved when people evaluate my choices or engage in moral prescriptives. When others invite us to live differently than we do, we might see that as a betrayal of their professed love for us.

If we unwittingly embrace the prosperity gospel, then if we are consistently experiencing poor health, financial struggles, or are struggling to find a spouse, or fail to win the election, or if our book doesn’t get published or doesn’t sell, we might start to feel less loved by God. And if we see personal fulfillment as our greatest treasure, then love is going to be about others meeting our various needs, helping us feel fulfilled (whatever that looks like for us). So, when someone invites us to live chastely (forgoing perceived needs for physical intimacy) we might see that as an unconcern for us, an unloving thing to do.

But when we see reconciliation with God and moral transformation as our greatest value, then love might in fact look a lot like invitations to live our covenants. I might even see evidence of divine favor in my greatest disappointments. God loves me so much that He puts me in situations that force me to clarify my priorities and shed the baggage that separates me from Him. I might find the greatest manifestation of God’s love in the presence and gentle whisperings of the Holy Spirit, which convicts just as much as it reassures, and invites me to sacrifice just as much as it comforts.

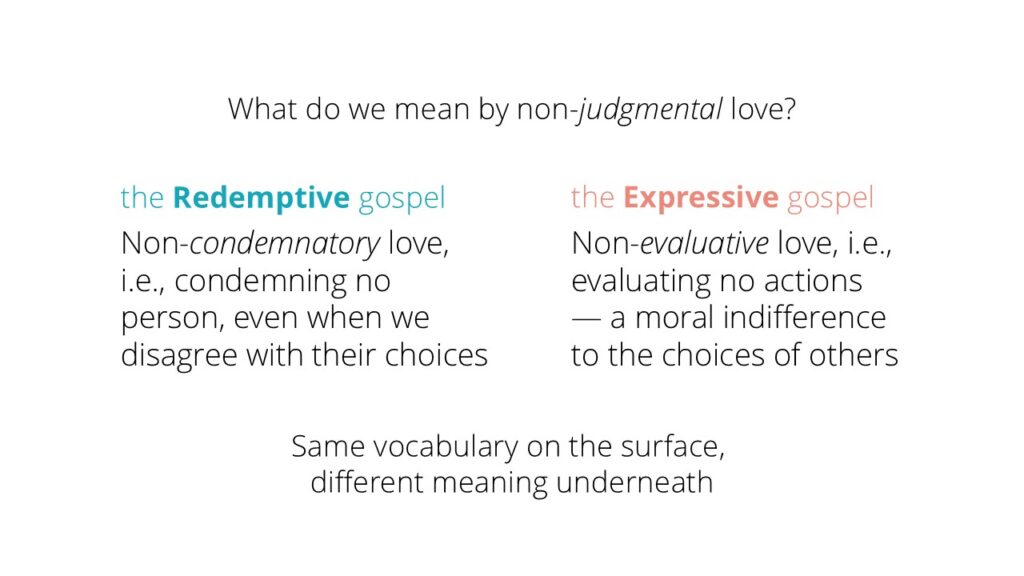

When two cultural tribes use the same words to mean different things, this is a recipe for conflict and confusion. When those who embrace the redemptive gospel view speak of non-judgmental love, they are typically talking about non-condemnatory love—condemning no person. When those who embrace the expressive gospel speak of non-judgmental love, they are often talking about non-evaluative love—evaluating no actions. When some among us declare that they do not feel loved by the community, sometimes this means we have more work to do in our ministering efforts. Other times, this means they have embraced a worldview — a gospel — that makes genuine Christlike love look like something else entirely. The worldview lens refracts the light so that we see strong Gospel norms as rejection.

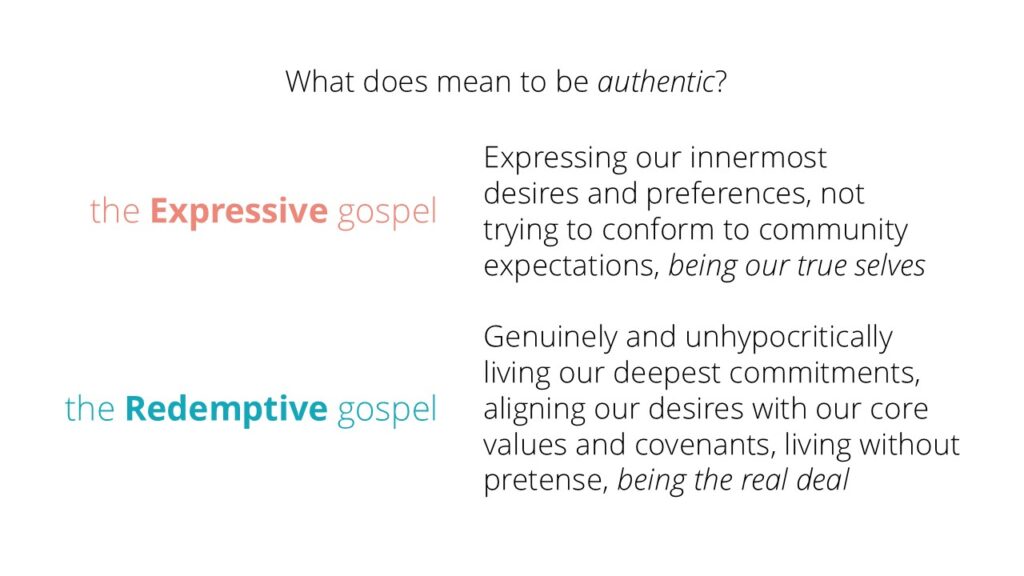

One more example. What does authenticity look like? For the sake of time, I’ll just do two worldviews on this one. In the expressive gospel, to be authentic means to express all my unique desires, preferences, characteristics — even if they are contrary to the norms and expectations of others. It means asserting myself on the world, being myself over and against all the moral prescriptives of faith and community. In contrast, if I embrace the redemptive gospel, authenticity might mean something fundamentally different — it might mean being genuinely good, unhypocritically diligent in my discipleship. It might mean not making a pretense of keeping the commandments or of living Christlike virtues, but being the real deal. And that’s not something we can do ourselves — we need Christ to change our very natures, to make us into new creatures by changing our fundamental values.

Conclusion

The existence of other worldviews is not (by itself) a problem. I think the Gospel is intended to be lived as one worldview among competitors. Mortality is a bubbling cauldron of worldviews so that we can (by contrast) more fully understand the Gospel as we live it. When family and friends embrace self-expression, personal fulfillment, or professional success as their guiding values, I think we can disagree without being disagreeable. We can embrace an ecumenical spirit and seek mutual understanding with those who embrace other worldviews. We can do this while still pursuing redemption and transformation through Christ as our guiding values (and inviting others to do the same).

But why, then, did I refer to these competing worldviews as gospel counterfeits? That is not very “ecumenical,” after all. When embraced on their own terms, other worldviews and values can be alternatives to the Gospel (when pursued as core values) or supplements to the Gospel (when pursued within proper bounds), but not necessarily gospel counterfeits. They become gospel counterfeits when they come to be seen as the Gospel of Jesus Christ—that is, when they are clothed in religious vernacular and treated as the scriptural message. Put in different terms, other worldviews become gospel counterfeits when:

- They shift what we see as the purpose of Gospel living.

- They become the main plot of our lives rather than merely a subplot.

- They redefine or co-opt important Gospel vocabulary.

When this syncretism distorts the purposes of the Gospel and redefines our core Gospel vocabulary, we need to become more culturally vigilant and discerning. The need for respect and kindness remains the same, but the need for clarity becomes more important than ever. Various cultural Influencers can unwittingly speak the familiar language of the Gospel, but—by reordering our values in subtle ways—offer a very subtle and at times pernicious counterfeit of the Gospel. The danger is that, though our vocabulary will remain the same, the core values of our faith will be replaced with the core values of a foreign worldview.

Rather than take offense at the notion that we sometimes embrace gospel counterfeits, we can take heart in the possibility of stepping into new and more sturdy faith. We can rejoice that whatever we thought the Gospel was, it might be so much better and so much more. A Gospel of Jesus Christ that promises us a transformation of character, reconciliation with God, and the gifts and fruits of the Spirit is more beautiful, hopeful, and ennobling than a gospel that promises us a life of comfort without disappointment, sacrifice, or grief, or mere personal fulfillment. And this Gospel has the benefit of also being more real.

coming soon

- Faith Crisis

- Misunderstanding Gospel principles through counterfeit worldviews.

- Disappointment when the Gospel doesn’t meet expectations based on cultural distortions.

- Membership Withdrawal

- Leaving the faith due to dissatisfaction with counterfeit Gospels rather than the true Gospel.

- Doctrinal Understanding

- Clarifying the redemptive purpose of the Gospel.

- Highlighting covenant-keeping, moral transformation, and reconciliation with God.

- Cultural Norms

- Recognizing how cultural influences can distort Gospel teachings.

- Navigating differences in worldview within faith communities.

- book of mormon

- mormonism

- faith crisis

- church

- doctrine

- gospel

- polygamy (for broader context on cultural critiques of Gospel principles)

- ces letter

- evidence

- science

- Faith Crisis

- Redemptive Gospel

- Prosperity Gospel

- Transformational Gospel

- Covenants

- Culture

- Worldviews

- Faith and Cultural Expectations

- Why Mormonism Doesn’t Work for Me

- Mormon Faith Crisis

- Covenant-Keeping in Mormonism

- Christlike Love

- Authenticity in Faith