“The Lord Was with Joseph”: A Scriptural Case Study in Why the Lord Allows Bad Things to Happen to Good People

by Matthew L. Bowen

Bad things happen to good people, of course. What’s more, sometimes terrible things happen to the best people even when they are striving with the utmost diligence to do what is right. The entire book of Job is “the paradigmatic literary case of the innocent sufferer, afflicted by the Deity through no fault of his own, and forever kept in the dark concerning the actual cause of his misery.”[1]

Nobody ever suffered more for doing so much good for so many than Jesus Christ himself, who never once committed sin.[2] Like Job, Joseph in Egypt represents an antetype or foreshadowing of the Savior with respect to unmerited suffering. As with Jesus and his atoning sacrifice, what happens to Joseph ultimately sets up the divine means of saving the house of Israel alive. This short study will explore the typology of Joseph as the life-saving sufferer (as opposed to a hapless victim of suffering) and the far-reaching impact of the divine deliverance accomplished through him.

“They Hated Him Yet the More for His Dreams”: Fraternal Resentment over Joseph’s Spiritual Gifts and His Favored Status

For Rachel, the birth of Joseph marked the reversal of longstanding infertility. She reflects the emotions of this reversal—“immense relief … and her hope of another child to come”[3]—in the naming of Joseph: “And she conceived, and bare a son [Hebrew bēn]; and said, God hath taken away [ʾāsap] my reproach: and she called his name Joseph [yôsēp]; and said, The Lord shall add [yōsēp] to me another son [bēn]” (Genesis 30:23-24).

As a Semitic/Hebrew name, Joseph means “May he [i.e., God] add.”[4] Rachel ties Joseph’s naming to the relief she felt at the Lord “taking away” (or “gathering up”) the “reproach” or stigma of her childlessness, but also to her hope of being “added” another son. Her express wish for another bēn anticipates the birth of Ben-Oni (“son of my strength” or “son of my sorrow”), renamed Benjamin (“son of the right hand”), the son whose birth ironically would cost Rachel her mortal life (see Genesis 35:18).

Jacob loved and Favored Joseph

Genesis 37–50 narrates Joseph’s life and the vicissitudes of his personal fortunes. From the beginning, the narrative makes clear that Jacob-Israel loved and favored Joseph over his other children: “Now Israel loved Joseph more than all his children, because he was the son of his old age” (Genesis 37:3). The narrator emphasizes that Joseph’s brothers fiercely resented and even hated Joseph not only because they witnessed their father’s preferential love for him (Genesis 37:4), but also because of his spiritual gifts. In particular, they “envied”[5] that the divine revelation received through these gifts pointed to a future in which Joseph occupied an elevated status above the whole family: “And Joseph [yôsēp] dreamed a dream, and he told it his brethren: and they hated him yet the more [wayyôsipû ʿôd]” (Genesis 37:5).

The narrator’s use of the phrase “yet the more” (wayyôsipû ʿôd) ties Joseph’s name (yôsēp) to the intensification of his brothers’ hatred in an ironic way: they added to hate. Joseph’s dreams specifically pointed to his brothers bowing down to him: “behold, your sheaves stood round about, and made obeisance [wattištaḥăwênā[6]] to my sheaf” (Genesis 37:7). The imagery of sheaf-binding as a symbol of lifesaving food—the significance of which only becomes apparent later in the story—is quickly overshadowed by the act of hištaḥăwâ—the Hebrew verb frequently translated into English as “worship.” It would be difficult to overstate the ritual and cultural significance of this term.

Hištaḥăwâ (perhaps originally from the idea of “causing oneself to live [through worship]”[7] in the presence of a divine being) is what ancient Israelites and Judahites came to the temple to do (see Psalm 5:7 [MT 8]; 95:6). It was this gesture, also sometimes called proskynesis, with which Jesus was reverenced during and after his mortal ministry[8] and which the Lamanites and Nephites received Jesus at the temple in Bountiful (see especially 3 Nephi 11:17-19; 17:10).[9] In both of the reported dreams in Genesis 37, this verb points to Joseph’s future royal—even divine—status. The imagery of ritually prostrating sheaves enrages Joseph’s brothers, who understand the full cultural implications of hištaḥăwâ: “And his brethren said to him, Shalt thou indeed reign over us? or shalt thou indeed have dominion over us? And they hated him yet the more [wayyôsipû ʿôd] for his dreams, and for his words” (Genesis 37:8).

The Similarities between Joseph and Nephi

The Latter-day Saint reader may be reminded here of Nephi’s autobiographical description of his similarly inimical relationship with his older brothers. Nephi described their anger and hatred for him in words deliberately drawn from the Genesis narrative, including an echo of the Joseph-wordplay in Genesis 37:5, 8. Nephi records: “But behold, their anger did increase [Heb. yāsap = add, increase] against me, insomuch that they did seek to take away my life. Yea, they did murmur against me, saying: Our younger brother thinks to rule over us; and we have had much trial because of him; wherefore, now let us slay him, that we may not be afflicted more because of his words. For behold, we will not have him to be our ruler; for it belongs unto us, who are the elder brethren, to rule over this people” (2 Nephi 5:2-3).[10]

Astral Imagery of Joseph’s Second Dream

Joseph had a subsequent dream that pointed in the same direction as the sheaves dream: “And he dreamed yet another dream, and told it his brethren, and said, Behold, I have dreamed a dream more; and, behold, the sun and the moon and the eleven stars made obeisance to me” (Genesis 37:9). Joseph’s brothers were already angry and envious, but this dream report even elicits a rebuking question from Jacob his father: “Shall I and thy mother and thy brethren indeed come to bow down ourselves [lĕhištaḥăwōt] to thee to the earth?”

Although Joseph offers no interpretation of the dream, Jacob clearly interprets the astral imagery—sun, moon, and stars—as symbolizing his family. Jacob apparently identifies the sun with himself and the moon with Joseph’s mother, Rachel (“thy mother,” Genesis 37:10). Robert Alter writes: “The second dream shifts the setting upward to the heavens and in this way is an apt adumbration of the brilliant sphere of the Egyptian imperial court over which Joseph will one day preside.”[11]

Alter further notes that “[t]his particular episode seems to assume, in flat contradiction of the preceding narrative, that Rachel is still alive, though Benjamin has already been born” (cf. Genesis 35:17-19).[12] Rather than constituting a clumsy narratological or editorial oversight, however, this detail and the heavenly setting of the dream may actually suggest that the timeframe for the complete fulfillment of Joseph’s dream extends well beyond the mortal lives of Jacob, Rachel, Joseph, and their family.

An Early Glimpse of the Eternal Nature of Families

In other words, Joseph’s dream portended that Rachel would live again in the postmortal sphere as would the entire family. Indeed, the story that follows shows how the evils imposed upon Joseph—by members of his own immediate family, no less—ultimately set up the divine means of saving the entire family alive, enabling the family’s perpetuation in fulfillment of the Abrahamic Covenant, the promises of which included the Messiah coming into the world through the lineage of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[13] The heavenly setting of Joseph’s dream constitutes an early glimpse of the eternal nature of the family as a fundamental aspect of the Abrahamic covenant.

The representation of Jacob-Israel’s sons as stars corresponds to the Lord’s comparison of Abraham’s seed to stars (see Genesis 15:5; Abraham 3:12-15) and the scriptural comparison of God’s children to stars (see, e.g., Job 38:7; Abraham 3:3-10, 16-25). Just as the temporal horizons for ultimate fulfillment of the Abrahamic Covenant stretch far beyond this mortal world, the temporal horizons for the complete fulfillment of Joseph’s dream of the sun, moon, and stars also extend into the eternities. Patriarchal blessings, some aspects of which seem to go unfulfilled in mortality for some individuals, have similar horizons of fulfillment.

“The Lord Was with Joseph”: The Typology of Unjust Suffering for the Saving of Life

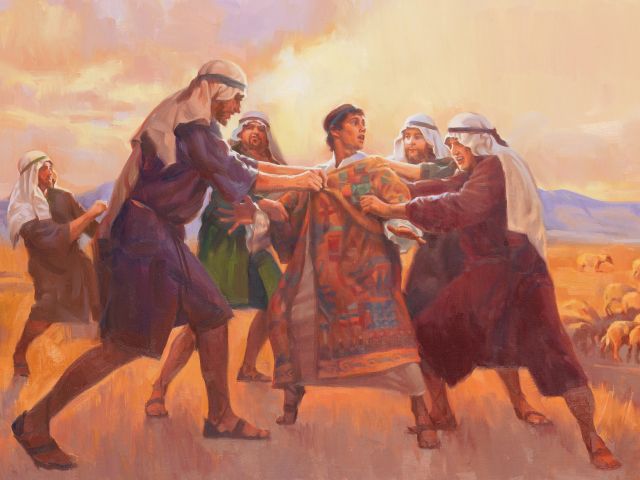

The remainder of chapter 37 details how Joseph’s hateful, jealous brothers stripped him of his coat and cast him into a pit, deliberately reducing his status, actions which eventuated in Joseph being sold by Ishmaelites as a slave into Egypt. After a narrative aside involving Judah in Genesis 38, Chapter 39 resumes the story, and ends with two similarly-worded statements, a framing device sometimes called inclusio, which emphasizes that the Lord continued to be “with Joseph,” in all his trials and troubles.

The opening frame marks a seeming improvement in Joseph’s circumstances and status: “And the Lord was with Joseph, and he was a prosperous man; and he was in the house of his master the Egyptian. And his master saw that the Lord was with him, and that the Lord made all that he did to prosper in his hand” (Genesis 39:2-3).

Living Righteously, Yet Everything Goes Wrong

Quickly, however, Joseph’s circumstances and status go from bad to worse as he is falsely accused of attempted rape by the wife of Potiphar (Genesis 39:7-20), and Joseph finds himself as a slave in prison—rock bottom in terms of status in the ancient world. Joseph was living righteously and yet everything seemed to be going wrong. At best, Joseph must have felt “perplexed, but not in despair” as Paul puts it (2 Corinthians 4:8), or at worst utterly abandoned as Jesus felt on the cross (see Mark 15:34; Matthew 27:46; cf. Psalms 22:1). Perhaps Joseph felt like his descendant Joseph Smith, who was doing his best to do God’s will when he was imprisoned in Liberty Jail (“O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?” D&C 121:1).

The closing frame of the inclusio reemphasizes that the Lord was still “with Joseph” in his changing circumstances, even as those circumstances only slowly improved at first: “But the LORD was with Joseph, and shewed him mercy, and gave him favour in the sight of the keeper of the prison. … The keeper of the prison looked not to any thing that was under his hand; because the Lord was with him, and that which he did, the Lord made it to prosper” (Genesis 39:21, 23). In chapter 40, Joseph uses his spiritual gifts to interpret the inspired, symbolic dreams of Pharaoh’s “butler”—mašqê, really “cupbearer”[14]—and baker who are imprisoned with him. Nevertheless, by the end of Genesis 40, the cupbearer, who had been freed and elevated to his former position as Joseph foretold, forgets Joseph and he seems hardly better off than when Potiphar cast him into prison.

The Lord’s Timing

But everything changes in the Lord’s timing. The same God who sent inspired dreams to Joseph, the cupbearer, and the baker, now sends one to Pharaoh (Genesis 41:1-7), as he begins to orchestrate Joseph’s deliverance and elevation to royal status. When the Egyptian ritual specialists fail to interpret Joseph’s dream (Genesis 41:8), the cupbearer finally remembers Joseph (Genesis 41:9). Notably, the maddeningly unjust delay caused by the cupbearer’s forgetfulness prepares the way for Joseph to be lifted up out of his rock-bottom situation to an even higher station than would have ever otherwise been possible, thus enabling Joseph to save his family.

In orchestrating Joseph’s ascension to “governor” or vice-regent of Egypt (Genesis 42:6; 45:26), the Lord saves the lives of many Egyptians and others, including the whole family of Jacob-Israel. The narrator emphasizes that it was in the high station that Joseph’s brothers first came to “bow down” to him in fulfillment of his dream: “And Joseph was the governor over the land, and he it was that sold to all the people of the land: and Joseph’s brethren came, and bowed down themselves [wayyištaḥăwû] before him with their faces to the earth” (Genesis 42:6).

The narrator takes the additional step of showing how the brothers’ observance of hištaḥăwâ—“caus[ing] oneself to live”—interplays with the preservation of Jacob’s life: “And when Joseph came home, they brought him the present which was in their hand into the house, and bowed themselves [wayyištaḥăwû] to him to the earth. And he asked them of their welfare, and said, Is your father well, the old man of whom ye spake? Is he yet alive [ḥāy]? And they answered, Thy servant our father is in good health, he is yet alive [ḥāy]. And they bowed down their heads, and made obeisance [wayyištaḥăwû]” (Genesis 43:26-28). These are not the final instances of their hierarchal prostration in his presence.

Typology of Life-saving in the story of Joseph

For his part, Joseph orchestrates to have his father’s whole family brought down into Egypt in the ensuing chapters (Genesis 42–46). Moreover, it is worth noting the typology of life-saving in the Joseph story and how Moroni links it to Joseph’s name and to the “remnant” of Joseph’s posterity in Ether 13:

And he spake also concerning the house of Israel, and the Jerusalem from whence Lehi should come—after it should be destroyed it should be built up again [yôsîp], a holy city unto the Lord; wherefore, it could not be a new Jerusalem for it had been in a time of old; but it should be built up again [yôsîp], and become a holy city of the Lord; and it should be built unto the house of Israel—and that a New Jerusalem should be built up upon this land, unto the remnant [cf. Heb. šĕʾērît] of the seed of Joseph [yôsēp], for which things there has been a type. For as Joseph [yôsēp] brought his father down into the land of Egypt, even so he died there; wherefore, the Lord brought a remnant [šĕʾērît] of the seed of Joseph out of the land of Jerusalem, that he might be merciful unto the seed of Joseph that they should perish not, even as he was merciful unto the father of Joseph that he should perish not. Wherefore, the remnant [šĕʾērît] of the house of Joseph shall be built upon this land; and it shall be a land of their inheritance; and they shall build up a holy city unto the Lord, like unto the Jerusalem of old; and they shall no more [wĕlōʾ yôsîpû] be confounded, until the end come when the earth shall pass away.

Moroni’s Word-play

Moroni seems to be engaging in a Hebraistic wordplay on the name Joseph (“may He [God] add,” “may He do again”) that emphasizes the connection between Joseph, his descendants, and iterative divine, restorative action.[15] Moroni uses another Joseph-wordplay in terms of “gather” (cf. Hebrew ʾāsap) to describe the Lord’s latter-day fulfillment of the Abrahamic covenant in gathering the family of Israel: “and they are they who were scattered and gathered in from the four quarters of the earth, and from the north countries, and are partakers of the fulfilling of the covenant which God made with their father, Abraham” (Ether 13:11). This wordplay recalls Joseph’s initial “gathering” of his brothers in Egypt: “And he [Joseph] put them all together [wayyeʾĕsōp, and he gathered them] into ward three days” (Genesis 40:3).[16]

Regarding the link between the Joseph story and Ether 13, John Tvedtnes once observed[17] that the use of the “remnant” (šĕʾērît) idiom used repeatedly here in Ether 13:7 recalls the very function of this idiom in Genesis 45:7: “And God sent me before you to preserve you a posterity [šĕʾērît, literally, ‘a remnant’] in the earth, and to save your lives [ûlĕhaḥăyôt] by a great deliverance.”

Tvedtnes further noted that “[t]he Genesis passage is particularly interesting because of its subtle yet telling contextual affinity to the way the Book of Mormon typically uses the expression ‘remnant of Joseph.’ In both cases the expression appears in contexts that imply or directly convey the idea of being sent to another land in order to be preserved.”[18] Early church members in this dispensation knew something about “being sent to another land in order to be preserved,” as do many of the world’s refugees today, which still include Latter-day Saints. This remains an issue of enormous contemporary relevance.

“God Meant It unto Good”: Evil Intentions Subsumed into God’s Good Intentions

Reunited with his son Joseph near the end of his life, Jacob acknowledged the fulfillment of Joseph’s prophetic dreams in “saving” his whole house (family) from death and his whole house “bow[ing] down” to Joseph. JST Genesis 48:7-11 preserves this acknowledgement and accompanying prophecy:

And Jacob said unto Joseph, When the God of my fathers appeared unto me in Luz, in the land of Canaan; he sware unto me, that he would give unto me, and unto my seed, the land for an everlasting possession. Therefore, O my son, he hath blessed me in raising thee up to be a servant unto me, in saving my house from death; in delivering my people, thy brethren, from famine which was sore in the land; wherefore the God of thy fathers shall bless thee, and the fruit of thy loins, that they shall be blessed above thy brethren, and above thy father’s house; for thou hast prevailed, and thy father’s house hath bowed down unto thee, even as it was shown unto thee, before thou wast sold into Egypt by the hands of thy brethren; wherefore thy brethren shall bow down unto thee, from generation to generation, unto the fruit of thy loins forever; for thou shalt be a light unto my people, to deliver them in the days of their captivity, from bondage; and to bring salvation unto them, when they are altogether bowed down under sin. (JST Genesis 48:7-11)

Joseph prevailed as had Jacob

Joseph prevailed, as when Jacob wrestled with the divine “man” at Peniel and had “prevailed” with God. Jacob’s prophecies that Joseph’s “brethren” would continue to “bow down” unto him “from generation to generation, unto the fruit of thy loins forever” indicates that the horizon for the fulfillment of Joseph’s dream would continue through out time and into eternity.

Joseph’s brothers had “bowed down” to him, so too his father Jacob if one can count the instance in Genesis 47:31, but Joseph’s deceased mother had not. Joseph’s descendants would continue to play a life-saving role as a “light” that would help deliver the house of Israel in a future age when Israel would be in the “captivity” of sin, “bring[ing] salvation unto them, when they altogether bowed down under sin.”

Joseph’s brothers fear revenge

After Jacob’s death Joseph’s brothers still feared retribution at his hand in Egypt. Joseph’s brothers again bow down before him in proskynesis:

And they sent a messenger unto Joseph, saying, Thy father did command before he died, saying, so shall ye say unto Joseph, Forgive, I pray thee now, the trespass of thy brethren, and their sin; for they did unto thee evil: and now, we pray thee, forgive the trespass of the servants of the God of thy father. And Joseph wept when they spake unto him. And his brethren also went and fell down before his face; and they said, Behold, we be thy servants. And Joseph said unto them, Fear not: for am I in the place of God? But as for you, ye thought evil against me [ḥăšabtem ʿālay rāʿâ, intended evil]; but God meant it unto good [Heb. ḥăšābāh lĕtōbâ, intended it for good or planned it for good], to bring to pass, as it is this day, to save much people alive [lĕhaḥăyōt]. Now therefore fear ye not: I will nourish you, and your little ones. And he comforted them, and spake kindly unto them. (Genesis 50:16-21)

God’s Plan for Good

Joseph is untinctured by even a hint of desire for revenge. His response to his brothers clearly reflects mature perspective on what he has suffered and how it fit into God’s plan to bring about a greater long-term good in time and even in eternity. The repetition of the verb ḥāšab is obscured in the King James translation: the evil Joseph’s brothers intended against him, God intended for his good, the brothers’ good, the good of the family, and ultimately the good of the whole human family.

Joseph’s story thus teaches the powerful lesson that God’s intentions for good can subsume the very bad things that happen to us, even things others intend or devise for our hurt in the misuse of their moral agency. He does so not only for our benefit but for the benefit of others. Commenting on the phrase “willing to submit to all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon him” at the end of Mosiah 3:19, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland stated the following:

I think the only commentary needed for this verse might be regarding the line suggesting God “inflicts” trials and burdens upon us. In English, the word inflict, which comes from the Latin infligere, has at least two meanings. One is “to strike or dash against” and another is “to beat down,” but those definitions are not applicable to God or His angels. No, the proper definition of the word as King Benjamin used it is to allow “something that must be borne or suffered.” Now allowing something is a different matter! God can and will do that if it is ultimately for our good. I am going to say it again: God does not now nor will He ever do to you a destructive, malicious, unfair thing—ever.[19]

All these things shall give thee experience

The Lord certainly allowed Joseph in Egypt to experience all that he experienced. He knew, as he would later tell Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail regarding the latter’s afflictions: “all these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good” (D&C 122:7). Elder Holland further avers, “By definition and in fact, God is perfectly and thoroughly, always and forever good, and everything He does is for our good. I promise you that God does not lie awake nights trying to figure out ways to disappoint us or harm us or crush our dreams or our faith.”[20]

Lastly, Joseph’s use of the expression “to save alive” (lĕhaḥăyōt)—literally, “to cause to live”—in Genesis 50:20 recalls his use of the expression “to save your lives” in Genesis 45:7 (ûlĕhaḥăyôt). His repetition of this expression together with the narrator’s statement “and he comforted them” recalls the story of Noah and the Ark. Joseph saved life, like the Ark in its function (the same form, lĕhaḥăyōt is used in Genesis 6:19-20). And, like Noah (see Genesis 5:26; Moses 8:9; cf. Moses 7:44), he was the son that “comforted” his family (compare yĕnaḥămēnû to waynaḥēm ʾôtām).[21] In doing so, he typified Christ’s salvific and comforting roles, and was worthy of the gesture of hištaḥăwâ.

Conclusion

The Lord did not cause evil to befall Joseph but he decidedly allowed it. He honors moral agency as sacrosanct even when human beings callously take the lives of their fellow humans (cf. Alma 14:8-11). Nevertheless, he can turn the bad things that happen to us and even the bad things that people do to us into a life-saving blessing for us and many others. He can do this because of his atoning sacrifice, the ultimate instance of turning evil actions and injustice into life-saving good. He can thus “consecrate” all our “afflictions for [our] gain” (2 Nephi 2:2).

“The Lord was with Joseph” in Egypt throughout all his trials, just as he was “with” Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail and forever after (D&C 122:9). He was “with Joseph” just as he “stood by” Paul in prison, for whom the Lord also had a special mission to “bear witness” of him at Rome (see Acts 23:17). Joseph’s story is yet more evidence that the Lord “doeth not anything save it be for the benefit of the world” and always “doeth that which is good among the children of men” (2 Nephi 26:24, 33).

View footnotes and read more about Matt Bowen here.