Post 1 | Post 2 | Post 3 | Post 4 | Post 5 | Post 6 | Post 7 | Post 8 | Post 9

Post 5 of 9

by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

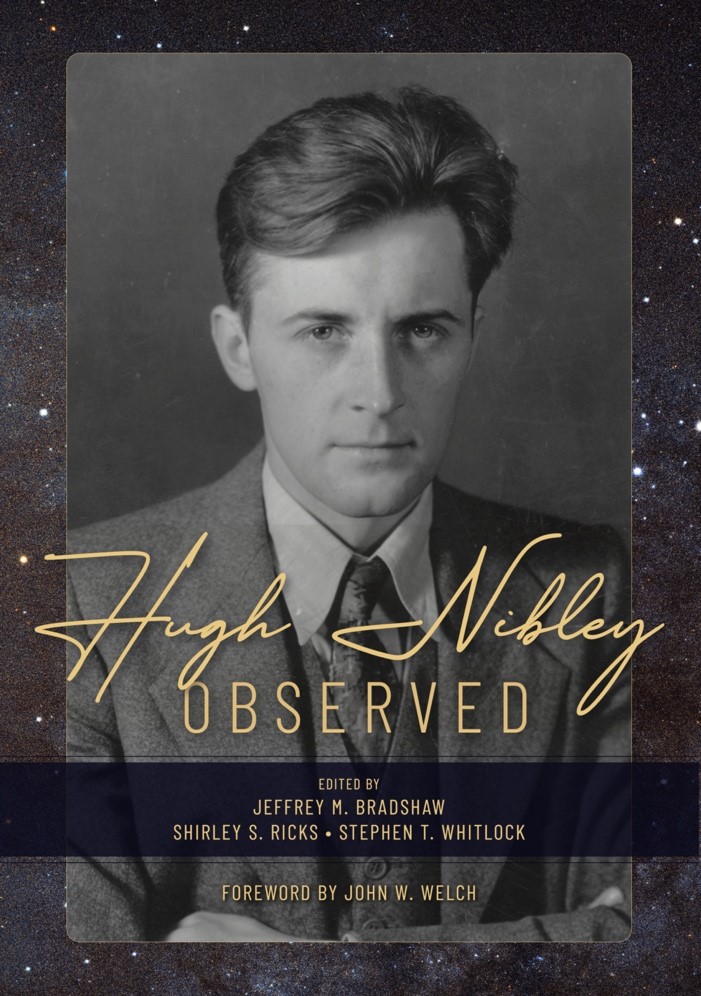

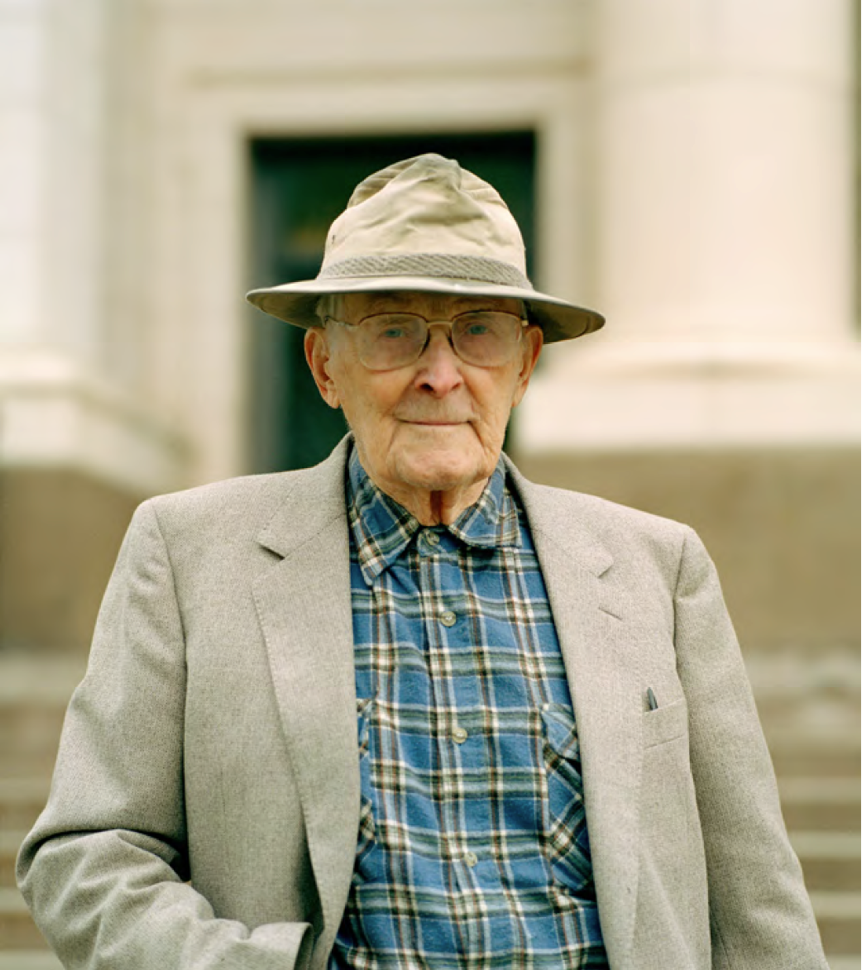

This is the fifth of nineweekly blog posts published in honor of the life and work of Hugh Nibley (1910–2005). The series is in honor of the new, landmark book, Hugh Nibley Observed, available in softcover, hardback, digital, and audio editions. Each week our post is accompanied by interviews and insights in pdf, audio, and video formats. (See the links at the end of this post.)

The premise of this week’s essay is that Hugh Nibley is more important now than ever. Why is this so?

Outlined briefly below is the way in which Nibley embodied four important personal qualities. Rare qualities then and rare qualities today — but absolutely essential elements in the 72-hour spiritual survival kit for Latter-day Saints growing up in the world in which we now live.

1. He knew the difference between the “terrible questions” and the trivial questions. Such questions are terrible not in the sense they are bad questions but in the sense that they may strike terror in the hearts of those who lack answers. They are questions that can only be answered through revelation: “Will there be life after death? What is it like? … Where did I come from? Why am I here?”[1] Nibley contrasts these to the “trivial questions,” like the ones Nibley received from the notorious Mark Hofmann, a fellow prisoner at the Utah State Penitentiary. Writes Nibley:[2]

You’d think the smart Mark Hofmann … would be able to come up with something better than three questions which “absolutely demolish Joseph Smith”: the Kinderhook Plates, no horse bones found in South America, and Adam-God — the old anti-Mormon chestnuts. …

You see how feeble the approaches of these attacks are, how irrelevant. What does any of this have to do with the eternities, with eternal life? What does any of this have to do with anything that interests me at all? There is only one question, the sole question for religion existing at all. Religion alone is supposed to answer it, and if religion can’t, then religion can’t do anything — let us forget religion. I don’t worry about tomorrow’s football scores; I don’t worry about all these questions concerning the nature of God. …

The real question, of course, is, Is this all there is? This is what everybody wants to know, the only question that bothers us.

Because Nibley could distinguish the terrible questions from the trivial questions, his life stayed centered on the things that mattered most.

2. He read old books. In a day when reading old thick books — especially books in lost languages — is increasingly rare, Hugh Nibley was an anomaly. Because Nibley read old books he, of course, knew the past. But, in addition, his reading of old books enabled him to take authoritative bearings on the present — one reason why his commentary on modern life is so incisive. As my beloved BYU English professor Arthur Henry King used to say, “He knows not the Wasatch Front, who only the Wasatch Front knows.” Knowing other times and places — in particular prior to the present loss of “immediate certainty” of the moral and spiritual in Western culture[3] — saves us from the errors of our own time and place. As C. S. Lewis explained:

It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to three new ones.

Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period.[4] …

We need intimate knowledge of the past. Not that the past has any magic about it, but because we cannot study the future, and yet need something to set against the present, to remind us that periods and that much which seems certain to the uneducated is merely temporary fashion.

A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village: the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.[5]

Because Nibley knew the ancient world, in its sacred and profane manifestations, he was both aware of the bright opportunities and wary to the insidious dangers of modern times.

3. He believed in and was a preeminent explorer of an “expanding gospel.” Nibley used this term to refer not only to the phenomenon of an open-ended canon due to continuing revelation but also to the miraculous recovery of fragments of inspired religious teachings in new discoveries of ancient apocrypha and pseudepigrapha from pre-rabbinic Judaism and early Christianity, as well as religious texts from pagan sources. According to most of mainstream Judaism and Christianity these sorry fragments of admittedly mixed, uncertain, and checkered provenance have little of value to teach us, but to Nibley they were, despite their imperfections, valuable witnesses of truths known anciently. By way of analogy he wrote:[6]

If one makes a sketch of a mountain, what is it? A few lines on a piece of paper. But there is a solid reality behind this poor composition; even if the tattered scrip is picked up later in a street in Tokyo or a gutter in Madrid, it still attests to the artist’s experience of the mountain as a reality. If the sketch should be copied by others who have never seen the original mountain, it still bears witness to its reality. So it is with the apocryphal writings: most of them are pretty poor stuff, and all of them are copies of copies. But when we compare them we cannot escape the impression that they have some real model behind them, more faithfully represented in some than in others. All we ever get on this earth, Paul reminds us, is a distorted reflection of things as they really are (1 Corinthians 13:12). Since we are dealing with derivative evidence only, we are not only justified but required to listen to all the witnesses, no matter how shoddy some of them may be.

As Truman G. Madsen expressed it:[7]

If the outcome of hard archeological, historical, and comparative discoveries in the past century is an embarrassment to exclusivistic readings of religion, that, to the [Latter-day Saint], is a kind of confirmation and vindication. His faith assures him not only that Jesus anticipated his great predecessors (who were really successors) but that hardly a teaching or a practice is utterly distinct or peculiar or original in His earthly ministry. Jesus was not a plagiarist, unless that is the proper name for one who repeats Himself. He was the original author. The gospel of Jesus Christ came with Christ in the meridian of time only because the gospel of Jesus Christ came from Christ in prior dispensations. He did not teach merely a new twist on a syncretic-Mediterranean tradition. His earthly ministry enacted what had been planned and anticipated “from before the foundations of the world” (See, e.g., John 17:24; Ephesians 1:4; 1 Peter 1:20; Alma 22:13; D&C 130:20; Moses 5:57; Abraham 1:3), and from Adam down.

Because Nibley believed that new discoveries in ancient digs and ancient texts bore witness that truths and records of historical events restored in our day were also known in former times, he saw them as a “reminder to the Saints that they are still expected to do their homework and may claim no special revelation or convenient handout as long as they ignore the vast treasure-house of materials that God has placed within their reach.”[8]

4. He had a testimony. Though Nibley said he had friends that said, as he put it, “not only that they don’t believe in such absurdity [as the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ], but [also] that they don’t believe for a minute that I believe in it,”[9] he had an unshakable testimony that was the central motivation of his life and work:[10]

I have a testimony of the gospel which I wish to bear. … As Brigham Young says, because I say it’s true doesn’t make it true, does it? But I know it is, and I would recommend you to pursue a way of finding out. And there are ways in which you can come to a knowledge of the truth.

When is a thing proven? When you personally think it’s so, and that’s all you can do. … Then you have your testimony, and all you can do is bear your testimony and point to the evidence. That’s all you can do. But you can’t impose your testimony on another. And you can’t make the other person see the evidence as you do. Things that just thrill me through and through in the Book of Mormon leave another person completely cold.

And the other way around, too. So we can’t use evidence, and we can’t [merely] say, I know this is true, therefore you’d better know it is true [by divine revelation]. But I know it is true, and I pray our Heavenly Father that we may all come to a knowledge of the truth, each in his own way.

***

We hope you will enjoy the video interview of Daniel C. Peterson embedded here, which you can view in either long or short form. Keeping with the theme this week of Nibley’s contributions to Latter-day Saint scripture scholarship, Dan, a BYU professor, an articulate and entertaining writer and lecturer on the faith, and president of the Interpreter Foundation recounts personal stories and descriptions of his experiences with Hugh Nibley over many years.

In addition, this week’s short Insight video asks the question, “Have Latter-day Saints Forgotten Hugh Nibley?” and gives several reasons why his amazing life and work will continue to inspire others for many generations to come.

A Conversation about Hugh Nibley with Daniel C. Peterson (complete)

A Conversation about Hugh Nibley with Daniel C. Peterson (short)

Insight – “Have Latter-day Saints Forgotten Hugh Nibley?”

References

Asad, Talal. “The construction of religion as an anthropological category.” In Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam, edited by Talal Asad, 27-54. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Shirley S. Ricks, and Stephen T. Whitlock, eds. Hugh Nibley Observed. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2021.

Lewis, C. S. “On the reading of old books.” In God in the Dock, edited by Walter Hooper, 200-07. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1970. http://www.pacificaoc.org/wp-content/uploads/On-the-Reading-of-Old-Books.pdf. (accessed August 8, 2017).

———. 1939. “Learning in war-time.” In C. S. Lewis: Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces, edited by Lesley Walmsley, 47-63. London, England: HarperCollins, 2000.

———. 1955. “‘De Descriptione Temporum’.” In Selected Literary Essays, edited by Walter Hooper, 1-14. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Madsen, Truman G. “Introductory essay.” In Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, Papers Delivered at the Religious Studies Center Symposium, Brigham Young University, March 10-11, 1978, edited by Truman G. Madsen. Religious Studies Monograph Series 4, xi-xviii. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978.

Nibley, Hugh W. “A New Look at the Pearl of Great Price.” Improvement Era 1968-1970. Reprint, Provo, UT: FARMS, Brigham Young University, 1990.

———. “The terrible questions.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 336–78. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. 1965. “The expanding gospel.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by D.E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 177-211. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

Petersen, Boyd Jay. Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2002.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

Notes

[1] B. J. Petersen, Nibley, p. 330.

[2] H. W. Nibley, Terrible Questions, pp. 338–339.

[3] C. Taylor, Secular Age, pp. 11ff. has discussed the process and consequences of this loss. See also T. Asad, Construction, pp. 47–52. C. S. Lewis, somewhat like Nibley, saw his extensive reading of “old books” as qualifying him to serve as a specimen of an almost extinct species that existed more commonly prior to the “great divide” (C. S. Lewis, Descriptione, pp. 11–14).

[4] C. S. Lewis, On the Reading, p. 202.

[5] C. S. Lewis, Learning, pp. 58–59.

[6] H. W. Nibley, Expanding 1992, p. 204.

[7] T. G. Madsen, Essay, p. xvii.

[8] From a chapter by Gary Gillum in J. M. Bradshaw et al., Hugh Nibley Observed, p. 735, citing H. W. Nibley, New Look, May 1970, p. 91.

[9] Hugh W. Nibley, chapter entitled “An Intellectual Autobiography,” in J. M. Bradshaw et al., Hugh Nibley Observed, p. 22.

[10] From the chapter of Shirley S. Ricks in ibid., pp. 486–487, citing

Latter-day Saint Scholars Testify, at https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/testimonies/scholars/hugh-nibley.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.