August 2019

August 2019

Jack: Welcome, and thank you all for coming this morning. Jeannie and I are honored by the privilege of addressing you, and we are grateful for our continuing, ongoing, and expanding collaboration with so many of you. Kudos especially to Scott Gordon and John Lynch, and all of their leadership that brings this conference together, year after year. Jeannie and I look forward to your questions today very much.

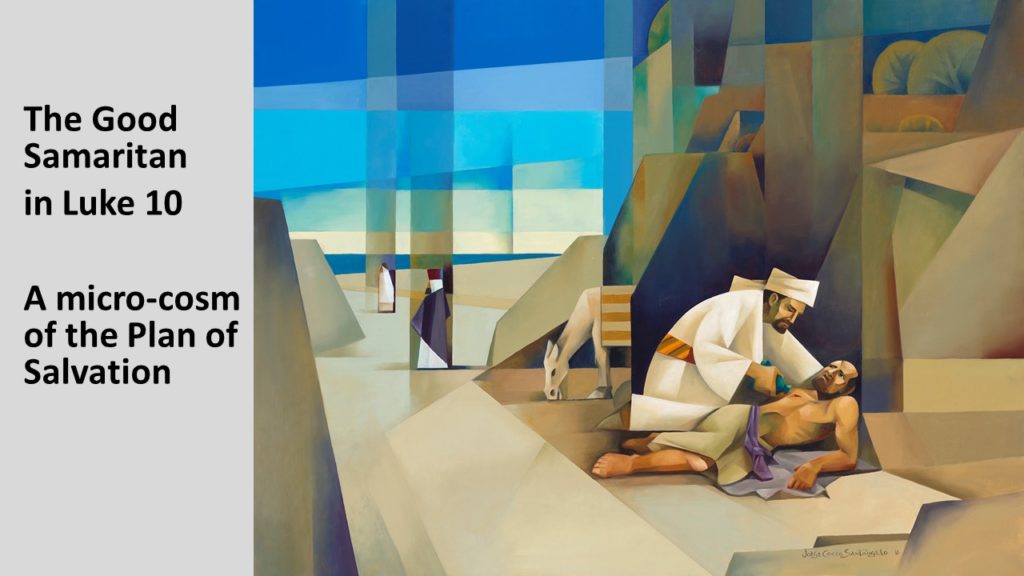

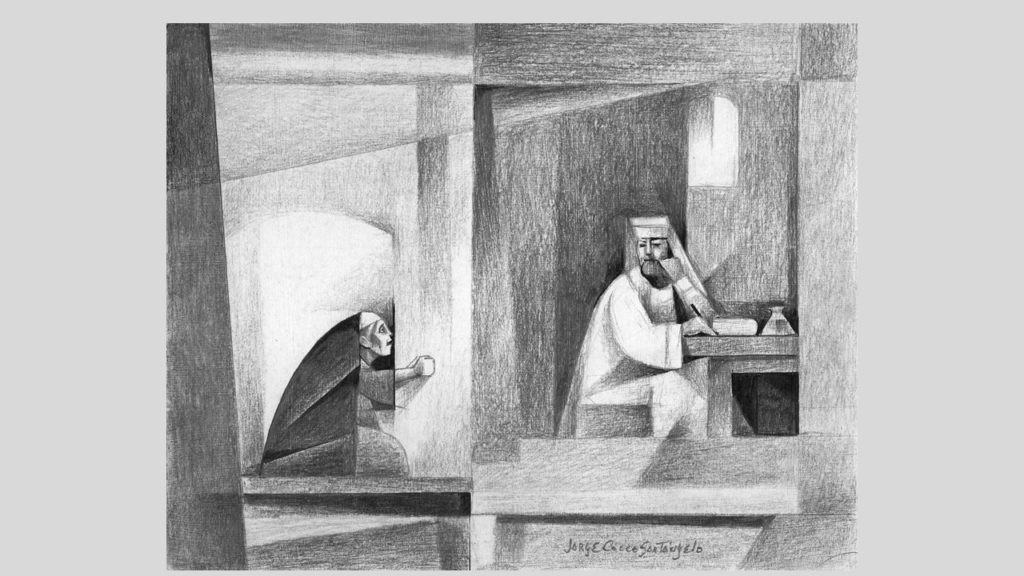

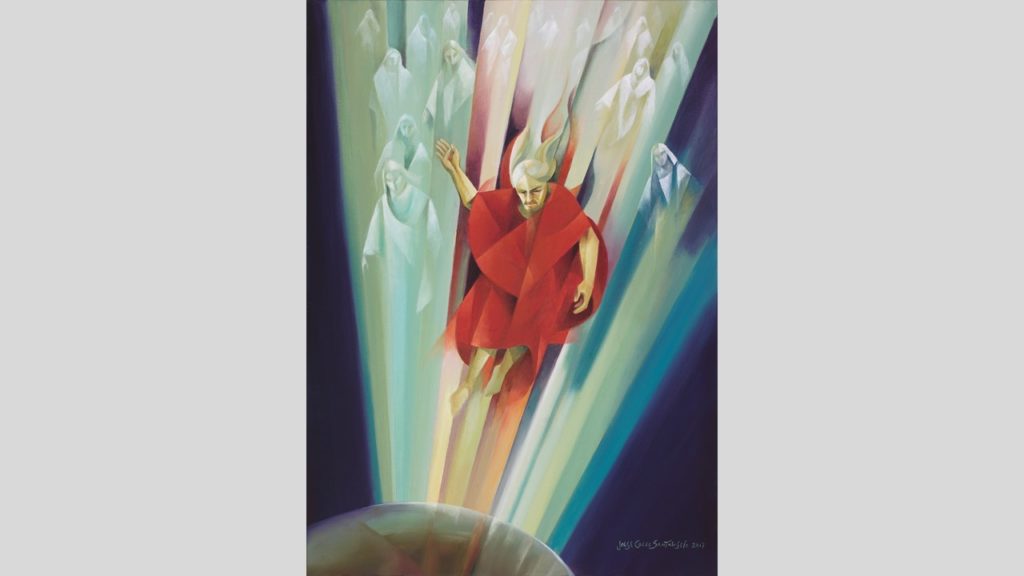

We wish to share with you our deep and tender testimonies of our enthusiasm for the truth and goodness of the parables of Jesus. We loved putting this book together, and love seeing the parables of Jesus in the light of the Plan of Salvation, as revealed by the restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ, especially in the Book of Mormon. This art and scripture study book [The Parables of Jesus Revealing the Plan of Salvation] has been a joy for us to produce as a couple. It includes a series of twenty-eight paintings we commissioned by the newly recognized and extraordinarily talented LDS artist Jorge Cocco, along with art commentary by Herman Du Toit about Coco’s ingenious sacro-cubist composition of each of these paintings.

Jeannie: As many of you know, Jack and I have been fascinated for many years by the parables of Jesus and their artistic renditions.

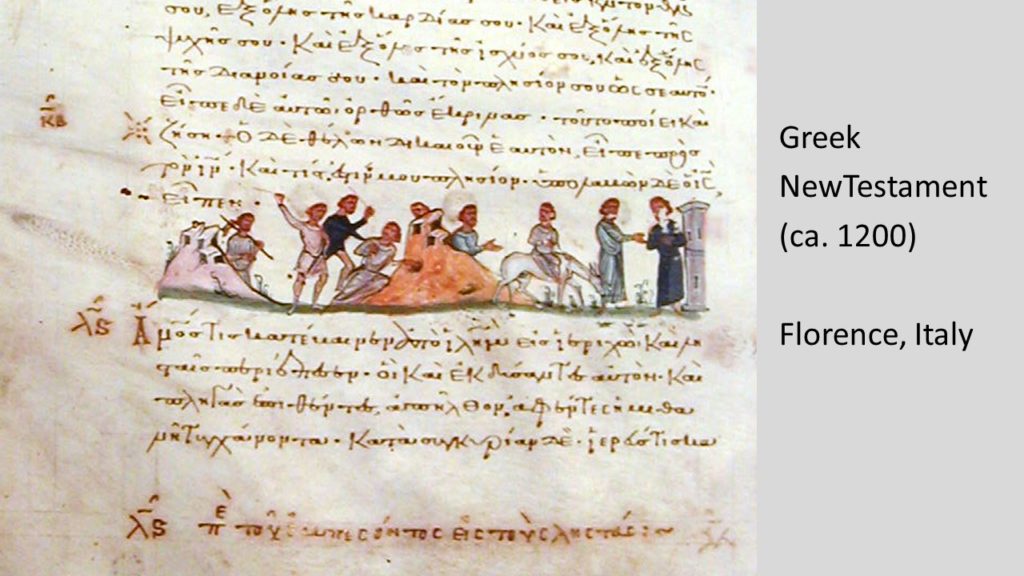

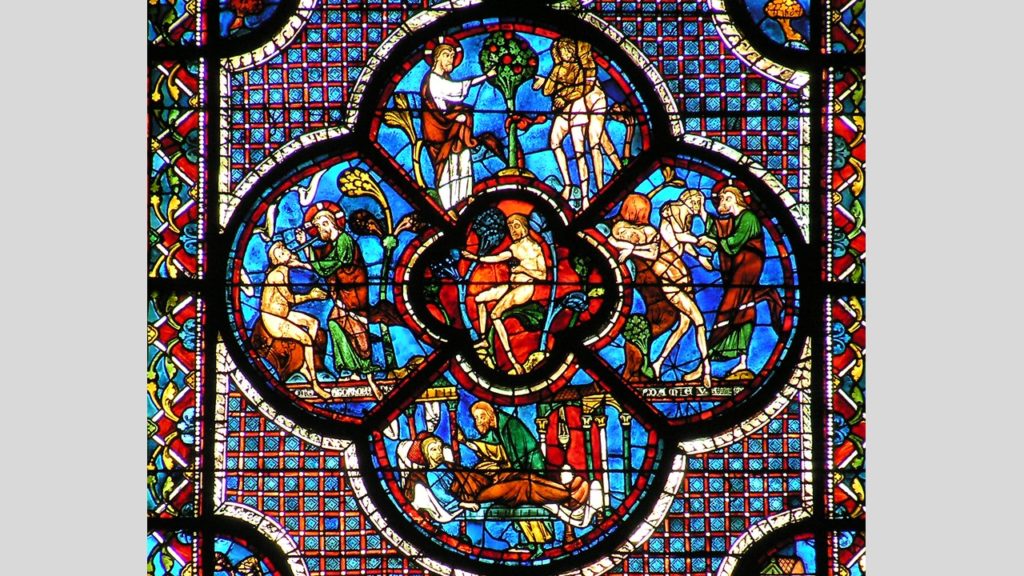

The Good Samaritan has been especially beautifully and meaningfully portrayed by artists over the centuries: in early New Testament manuscripts; in the stained glass windows of three French cathedrals, seen here in Chartres Cathedral;

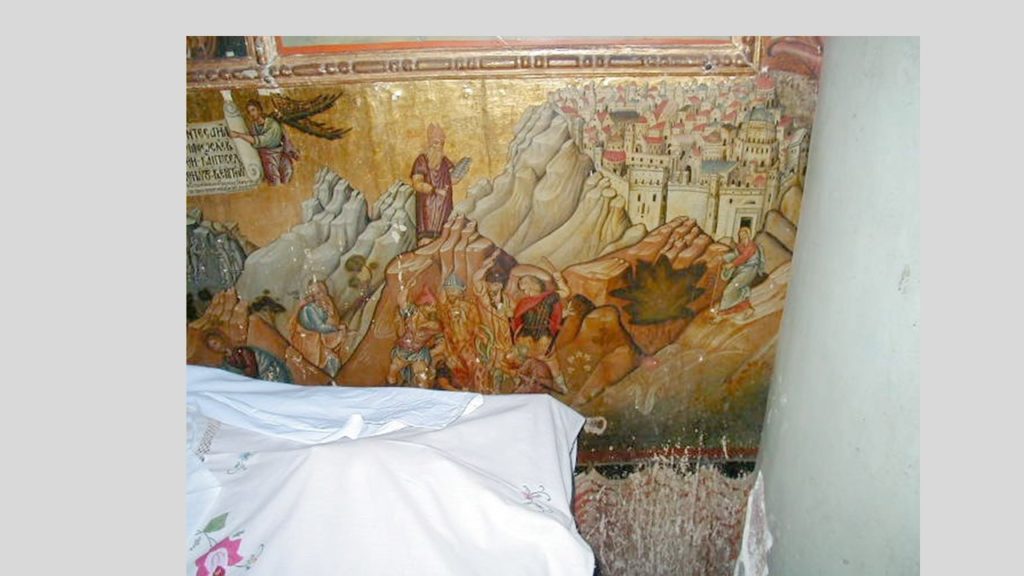

on the walls of Greek Orthodox chapels, seen here at St Catherine’s monastery, here in the Sinai – that was quite a trip, I assure you! –

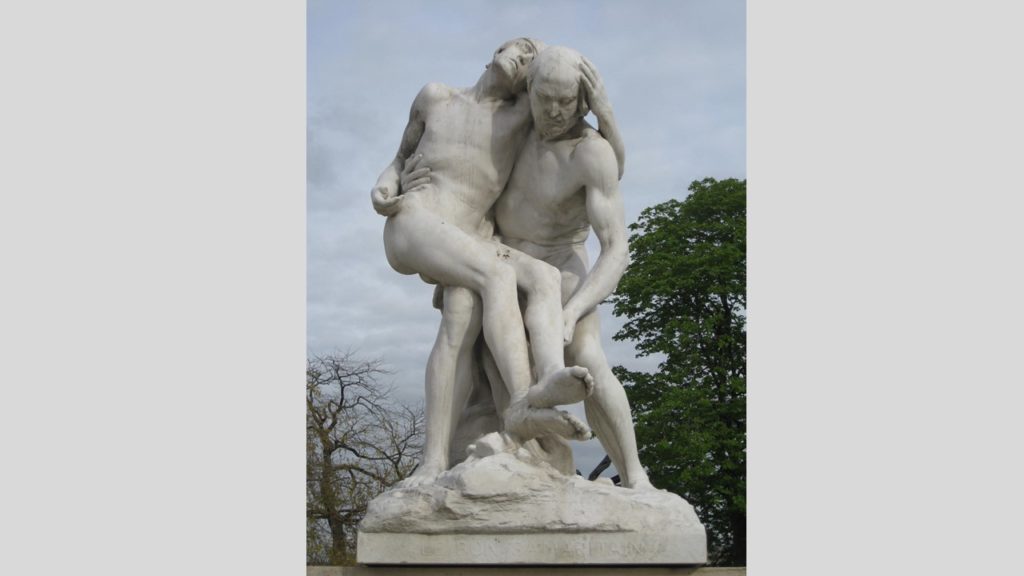

in statues, such as the one in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris;

and in paintings such as this little-known Cry for Help in a self-portrait by Van Gogh.

Jack: A self-portrait of Vincent Van Gogh, showing himself as the one who needed to be rescued.

We became particularly interested in the way in which the Good Samaritan was almost universally understood in early Christianity: as a detailed allegory of the Plan of Salvation. Here, for example, and quite amazingly, is how Origen, in the second century AD, had received and understood the classic parable. “The man who was going down was Adam; Jerusalem is Paradise, and Jericho is the world. The Priest is the Law; the Levite is the prophets; and the Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience; the beast is the Lord’s body; the pandocheion – that is, the stable – which accepts all (the Greek word pan) who wish to enter is the Church; and, further, the two denarii – the two coins – mean the Father and the Son. The manager of the stable is the head of the Church, to whom its care has been entrusted. And the fact that the Samaritan promises he will return represents the Saviour’s Second Coming.” -Origen

It was this interesting interpretation of the Good Samaritan that led Jeannie and me to wonder how many other parables – either alone, or as a group – might relate to what we call the Plan of Salvation. We also wondered why more of the parables had not been painted or portrayed artistically. What might be done about that? Enter: Jorge Cocco.

Jeannie: Jack and I first connected with Cocco when Cocco spoke to the BYU Studies Academy in 2016, just three years ago. His presentation there, along with an exhibit of the paintings of the life of Christ in the Church Museum of History and Art, led to Herman Du Toit’s essay about Cocco’s life and work in the BYU Studies Quarterly. All of this helped catapult this eighty-year-old Spanish-speaking Argentinian artist into immediate popularity in the Church. I am sure, as you look at his style, many of you will recognize many pictures that were used in this year’s Come, Follow Me manual – and he has become, so quickly, much beloved in our Church. More about him, and his style, can be found in chapter one of our book, and also on his website – and, once you get started, you’ll see his paintings everywhere. We were both just immediately drawn – as are many people – to his paintings; and we could see great possibilities for working together.

To our great delight, he responded enthusiastically to the idea of a collaborative effort – and, then, we commissioned him to produce the twenty-eight paintings and sketches of the parables that are seen in our book. Our collaboration with him was invigorating and inspiring. We presented to him our vision of organizing the parables according to their roles in the Plan of Salvation. And then Cocco’s genius went to work on how to portray the parables with this understanding in mind. We found that it was a collaborative effort, as he worked, and we looked, and answered, and responded (he changed sometimes); it was just a great, wonderful work of the three of us working together. We had found that the Plan of Salvation was like seeing the picture on the box as you try to gather the various “parable pieces” and put them together into one great, coherent whole. As Latter-Day-Saint interpreters, we all have a distinct advantage in the great foundation that the understanding of the Plan of Salvation gives us. This helps us believe and follow the teachings of Jesus more meaningfully – and more completely – and we hope the same experience will be for our readers.

Jack: So each chapter in the book covers several points: the sequential place of each parable in the Plan of Salvation is explained; we ask, and discuss, “Where is Jesus to be found in this parable?” The setting of each parable is described in the context of the ministry of Jesus; the text and translation of each parable is elucidated; explanatory commentary is given using the Greek and scholarly exegesis, along with insights afforded by the Plan of Salvation as taught in the Book of Mormon. And, finally, textual details are connected with Cocco’s portrayals in these new paintings.

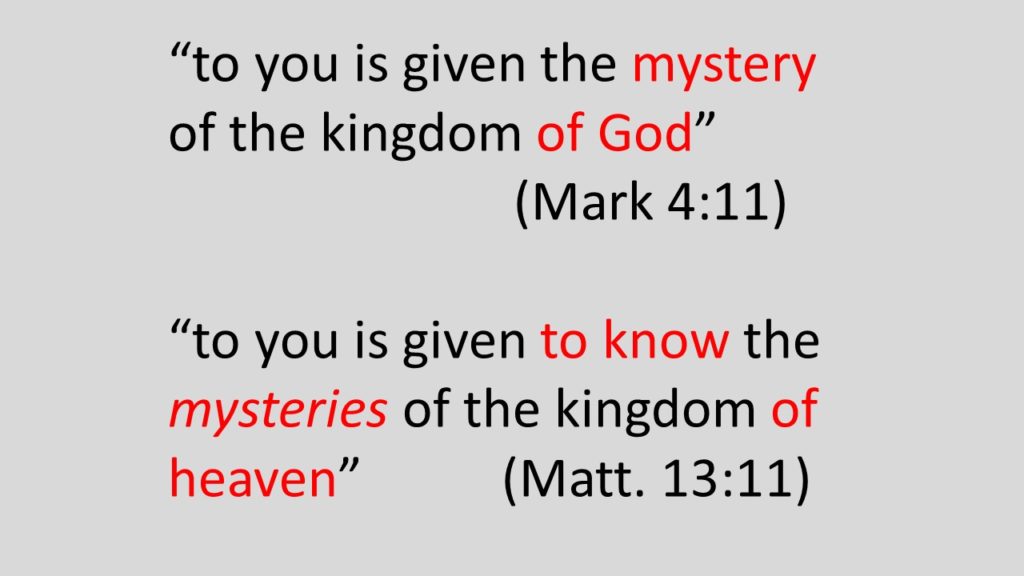

The point of departure in the book is the question the twelve apostles asked Jesus on one occasion, namely: “Why do you speak in parables”? As you’ll recall, Jesus answered, in essence: “People generally will understand some of what I’m saying, but other people, such as

you, will really get it – because to you”, he said, “is given the mystery of the Kingdom of God” in Mark 4; or, as Matthew 13 reads: “To you it is given to know the mysteries of the Kingdom of Heaven.”

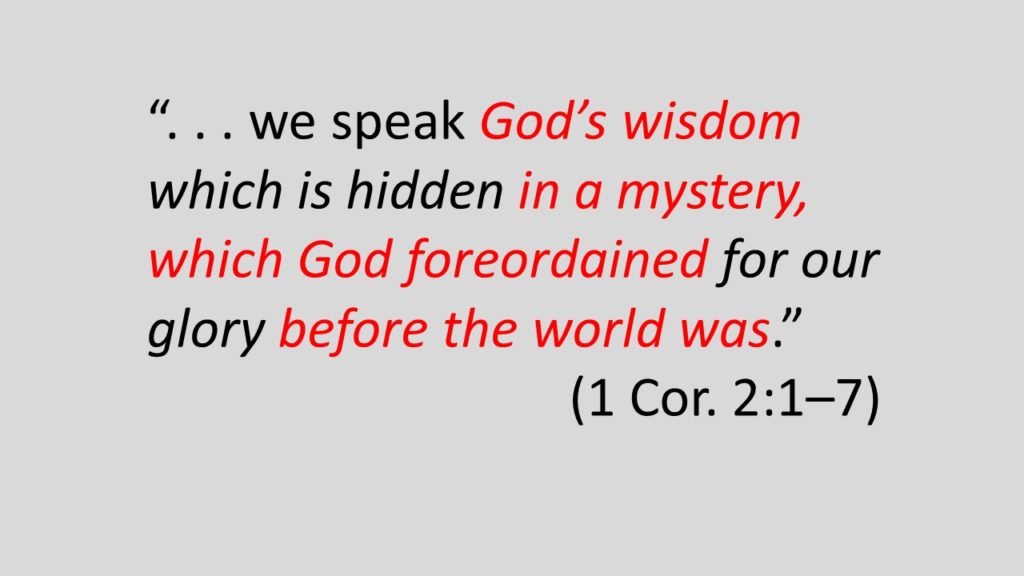

We learn from this that the disciples knew something that acted as a key to understanding Jesus’s parables. The apostle Paul makes it clear in 1 Corinthians, chapter 2 – as Michael Rhodes has recently (and very helpfully) explained – that the “mystery” is what we would call the Plan of Salvation: the Plan that God foreordained from the foundation of the world, before the world was. Indeed, in explaining one of the parables, Joseph Smith said: “The Great Plan of Salvation is a theme that ought to occupy our strict attention.”

Joseph sees this as a grand key that will unlock the most sacred message of each of Jesus’s parables. Seeing each parable as teaching an essential part of the Plan of Salvation, that Great Plan became the organizing principle behind our Table of Contents.

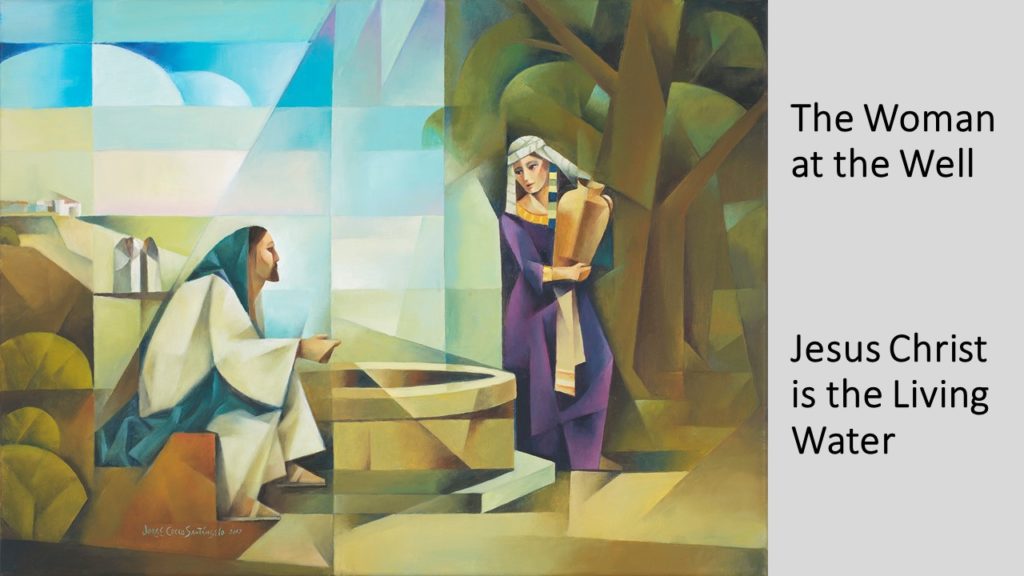

Jeannie: Because the overriding principle in the Plan of Salvation is faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, it’s easy to see that Jesus often painted Himself into His parables. He can readily be seen as the Samaritan, the Sower, the Gardener, the Rock, the Good Shepherd, the Forgiving Lord, and, obviously, the Son of the Lord of the Vineyard, killed by the wicked tenants; and, as well, the returning Bridegroom. In other parables the symbolism is less obvious; but if you read, seeking and asking “where is Jesus in this parable?”, you will find Him in almost every parable. Indeed, the greatest assurance that was given to all of us in the premortal Council was that all will have, eventually, the opportunity to find Jesus, and to recognize Him as our Savior; and everyone – even a marginalized Samaritan woman – could receive His gospel and obtain its living water.

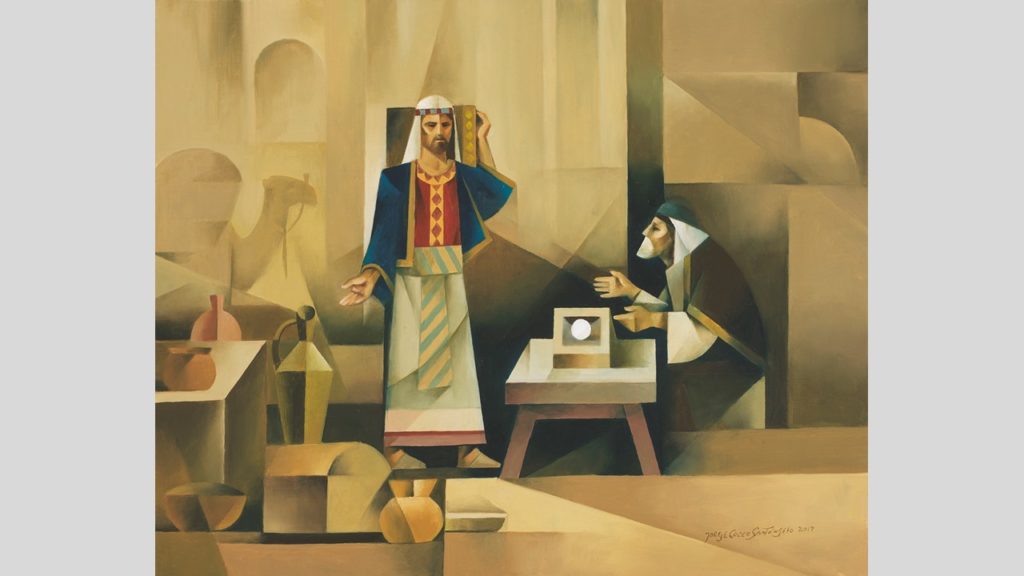

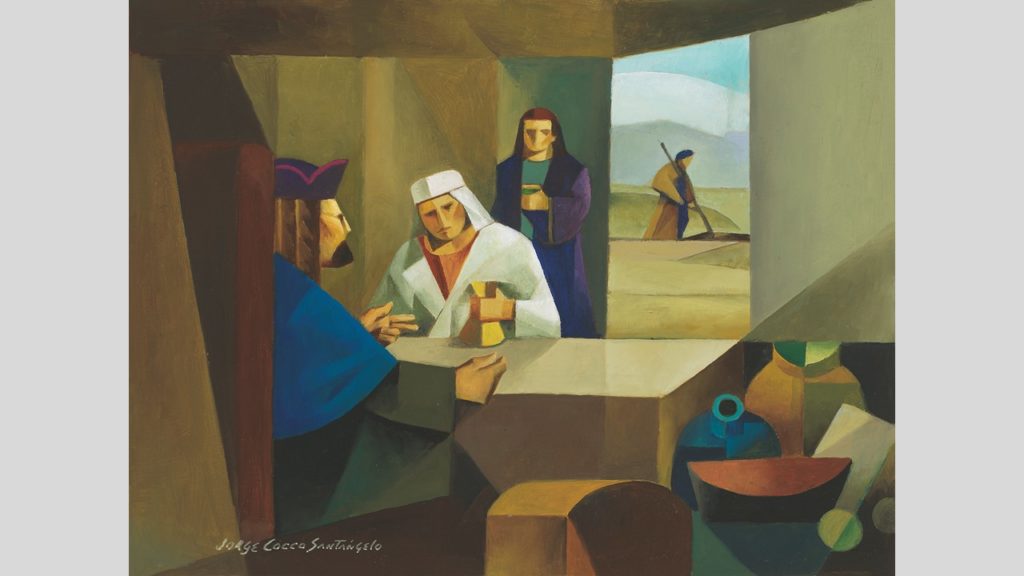

In this gorgeous painting, Cocco captures many wonderful details in the encounter when the woman of the well recognizes Jesus as He presented Himself to her, in a symbolic way, as one who has come into this world to give to us the living water of eternal life. Look at the painting, and notice how Cocco powerfully depicts the action of the Savior reaching out to her, penetrating the boundary between His celestial world and her mortal world, to invite her to listen to His message. Think – for just a minute – that, just previously, Jesus had spoken, at night, to Nicodemus – a man of great means and privilege – who came, curious, to Him – and yet, Nicodemus’ reaction was to immediately turn away and receive nothing. I love that the artist has painted the woman in royal purple, showing her true nobility of spirit as one who was so eager and ready to receive and believe His message that she became the first person to hear His announcement: “I, that speak unto thee, am He (meaning the Messiah).” John 4:26

Jack: As already mentioned above, Jesus’s most single overview of the Plan is found in the parable of the Good Samaritan, which stands as a microcosm of the Plan. Understood symbolically, it represents our coming down from a premortal, holy place, falling among evil forces, and being left exactly half-dead, having suffered one death, but not yet the second death, so to speak. But we are saved, washed, and anointed, with wounds bound up, taken to a house of healing, awaiting the promised return of that Savior. The entire Plan, so memorably portrayed here, with all of its many details, from start to finish, makes this parable one of the most read and quoted of all the parables.

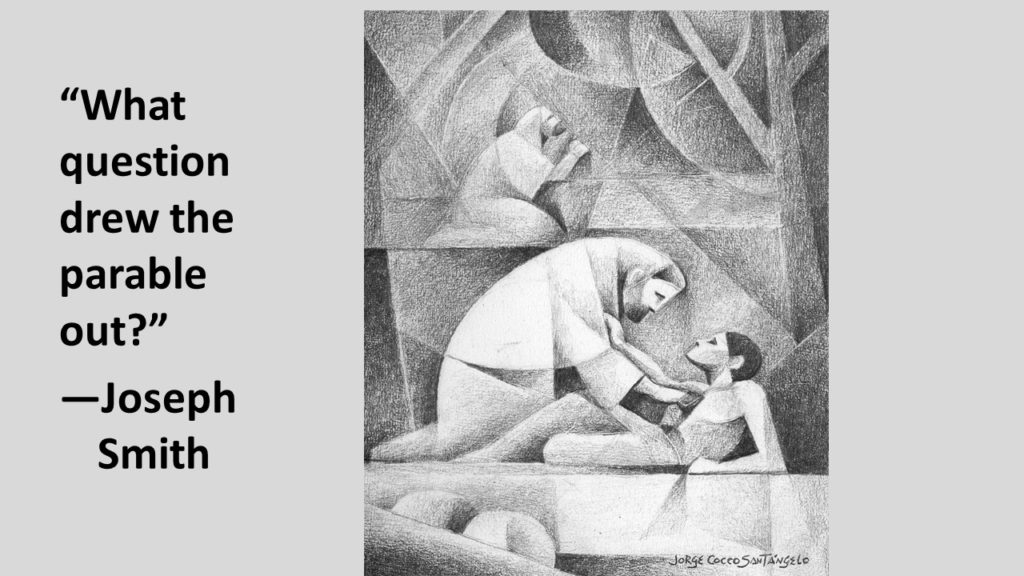

Jeannie: Joseph Smith gave us another very useful interpretive key in understanding the parables. He said: “If you want to understand the parable, ask yourself: ‘What question drew the parable out?’” Now, most people, in thinking of the Good Samaritan, would quickly say “Who is my neighbour?”; but actually, the lawyer asked a question earlier: “What must I do to [obtain] eternal life?” Luke 10:25 – or, in other words, “Tell me the Plan of Salvation.” And thus, in this drawing by Cocco, he has correctly placed Christ’s Atonement in the garden of Gethsemane directly in the victim’s line of vision, above and behind the life-saving work of the Samaritan.

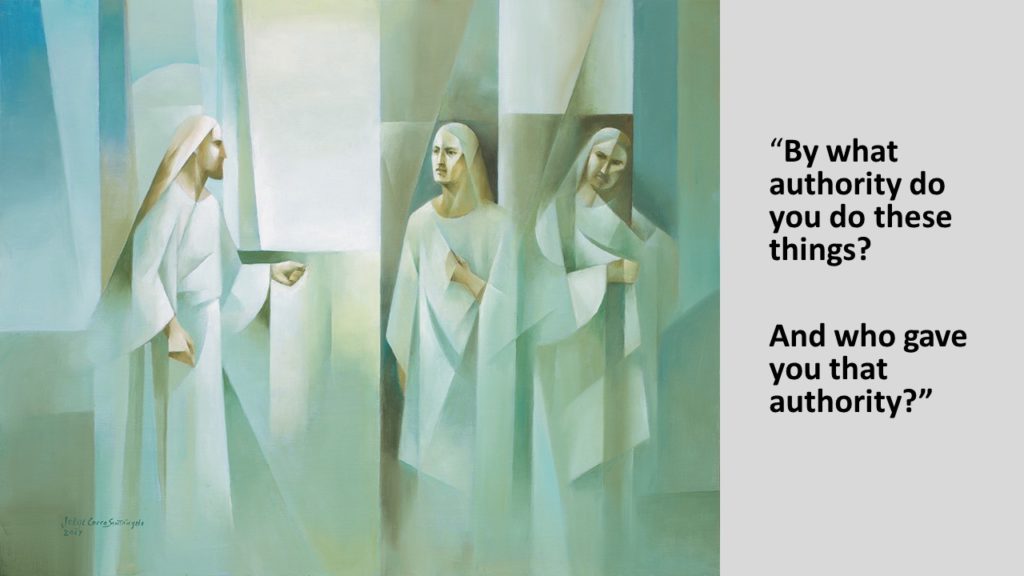

Jack: Taking us back to the premortal Councils is the little-used parable of the willing and unwilling two sons. Using Joseph’s key here opens the meaning of this parable of the certain man who had two sons.

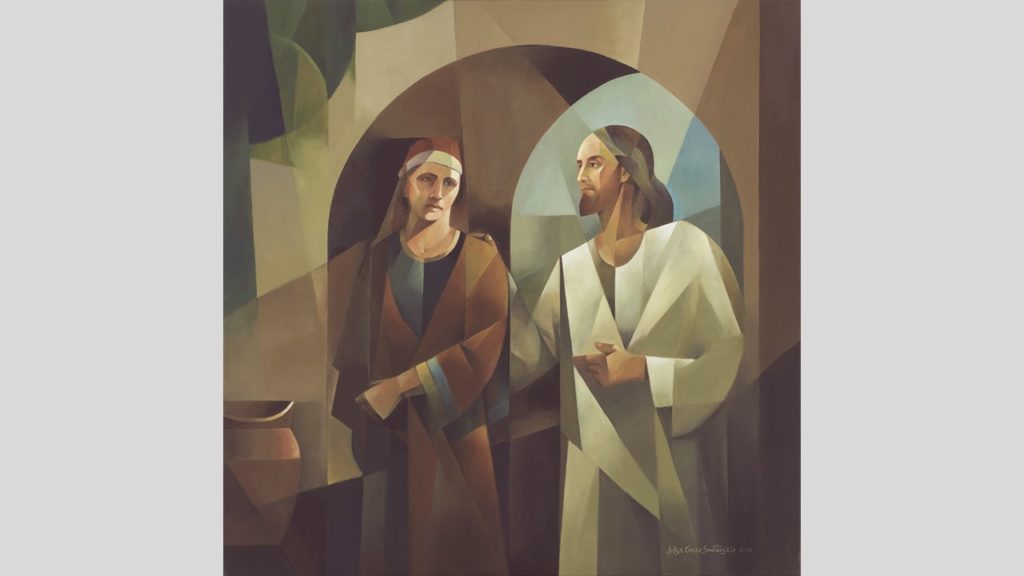

It was given by Jesus in response to the chief priests’ two questions as Jesus entered the temple – the day after His triumphal entry. Worried by what Jesus was doing, they asked: “By what authority are you doing these things? And who gave you that authority?” After a little discussion with them, Jesus gives His answer to these questions by telling this parable: how a father had asked his two sons to go down and labor in the vineyard that day. The original Greek of this passage makes it clear that the first son did not say “I will not go,” but: “I will it not; it is not my will”; but he reconciled Himself to the will of the Father, and he went forth with power and authority. The other son, of course, did not. Cocco’s depiction focuses on the decisive moment when the Father extended His assuring and determined hand to His first son. Well, that son – Jesus – places his hand submissively over his heart. Meanwhile, the other son – Lucifer – is exiting into the margins.

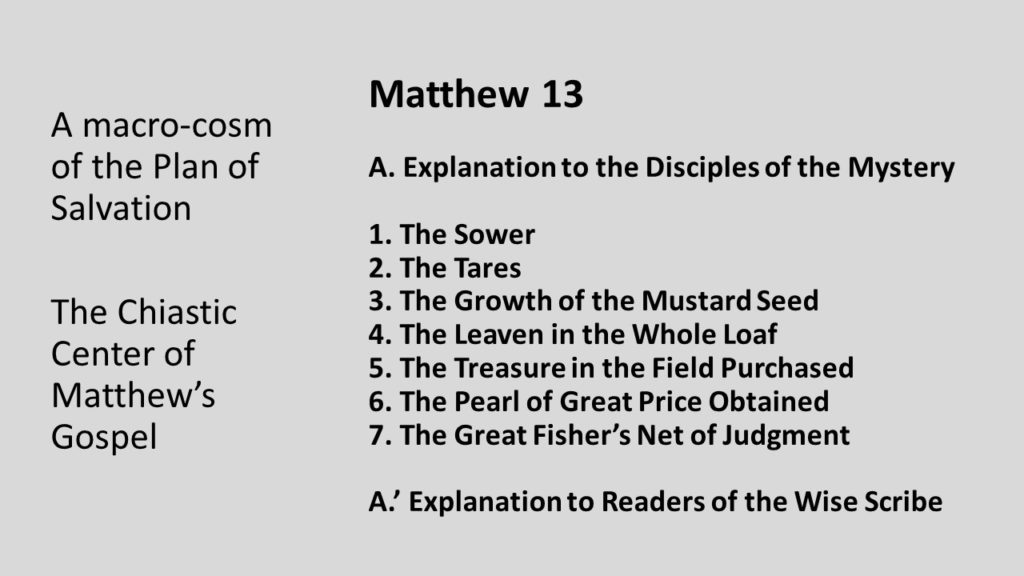

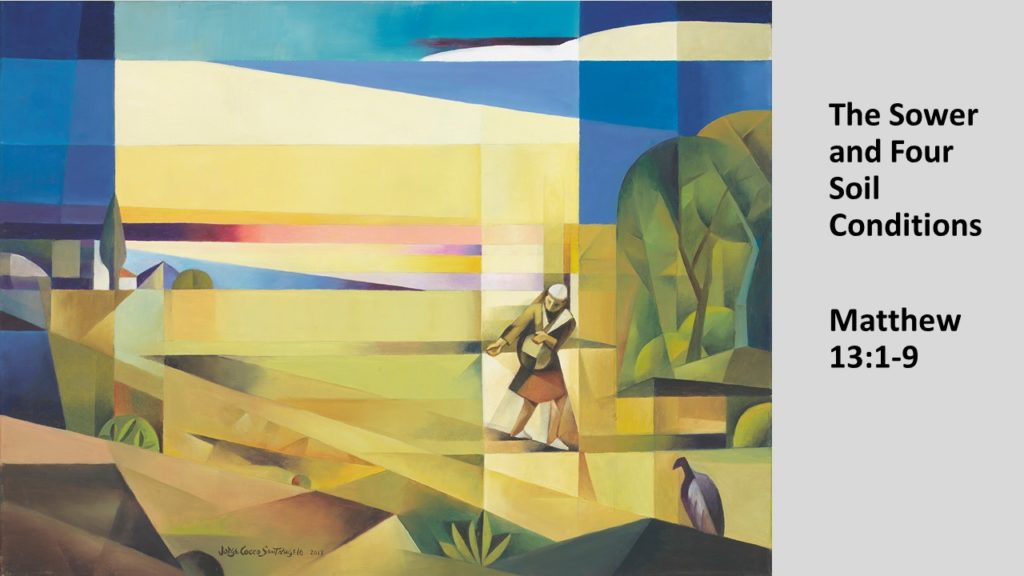

Jeannie: With this understanding in place, we then turn to Matthew 13. Matthew 13 gives a whole series of parables, and is often called Jesus’ “parable sermon.” It has been shown to be the chiastic center of all of Matthew’s gospel – and, in seven parables, it offers an overview – or macrocosm – of the Plan, from the sower to the tares, and ending with the great net of Judgement.

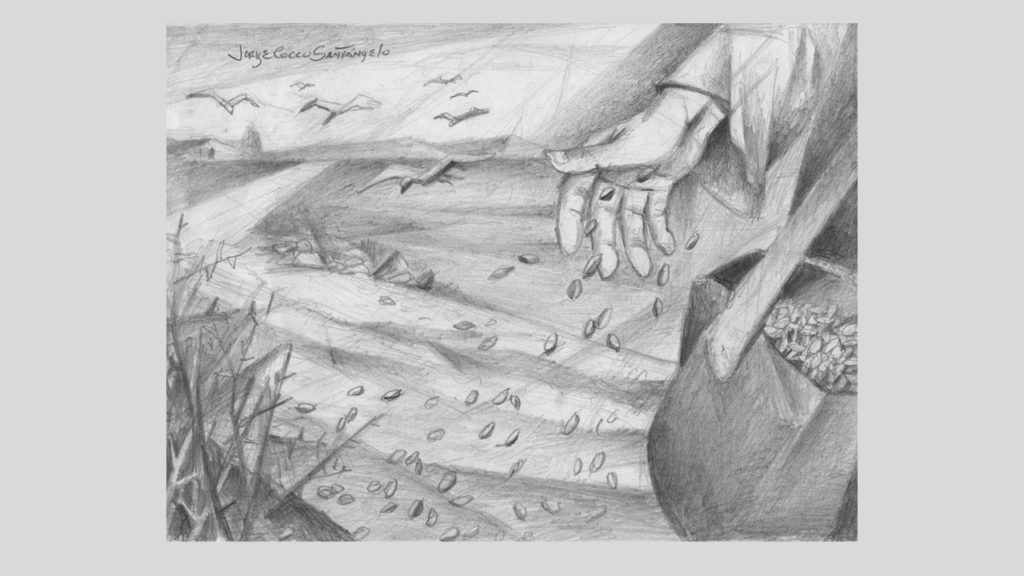

The first parable of Matthew 13 has been called by many names – the parable of the sower, or of the seeds, or of the soils. In the Plan of Salvation, life-bearing spirits come down on this earth, and these spirits are represented here by seeds.

As was understood in the Plan of Salvation, they will find themselves in various circumstances: some conducive of growth; others hampering growth by adverse conditions as the word of God is presented to them.

It is really important for us to note that the existence of these differences is not an unexpected aberration, but it is an integral part of the Plan. While the parable of the sower mentions the challenges of heat, weeds and birds as mortal enemies of the seeds, Cocco’s final portrayal optimistically minimizes the long-lasting effects of these forces – and looks forward, instead – as does the Father’s Plan – to the Lord’s ultimate promise of an abundant, bounteous harvest: thirty-, sixty-, and even one-hundred-fold.

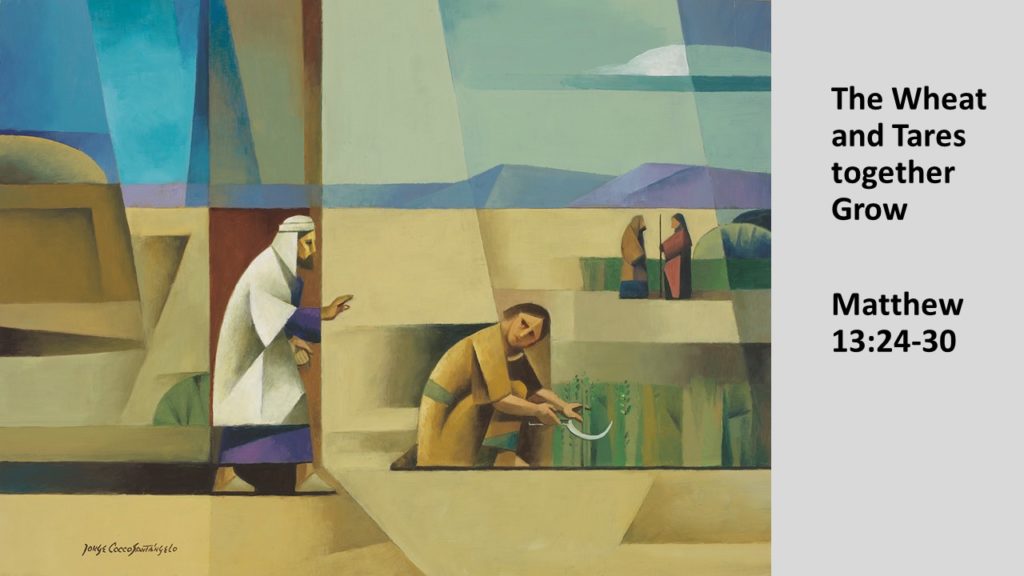

Jack: And the parable of the Sower directly gives rise to the next question: why must there be opposition in this world? That question is answered by the next parable of the wheat and tares.

Focusing not on the point that an enemy had sown the tares while men slept, as other artists have tended to do, Cocco shows the Lord directing His servant here to let the two grow together, for a season – because uprooting the tares will damage the wheat. This parable thus teaches about the great apostasy: how there will be good and wheat out there amidst the tares – and how it will eventually be, according to Doctrine and Covenants 86, the lawful heirs of the priesthood who will be able to distinguish between what is living wheat, ready for harvest, and what is empty tare.

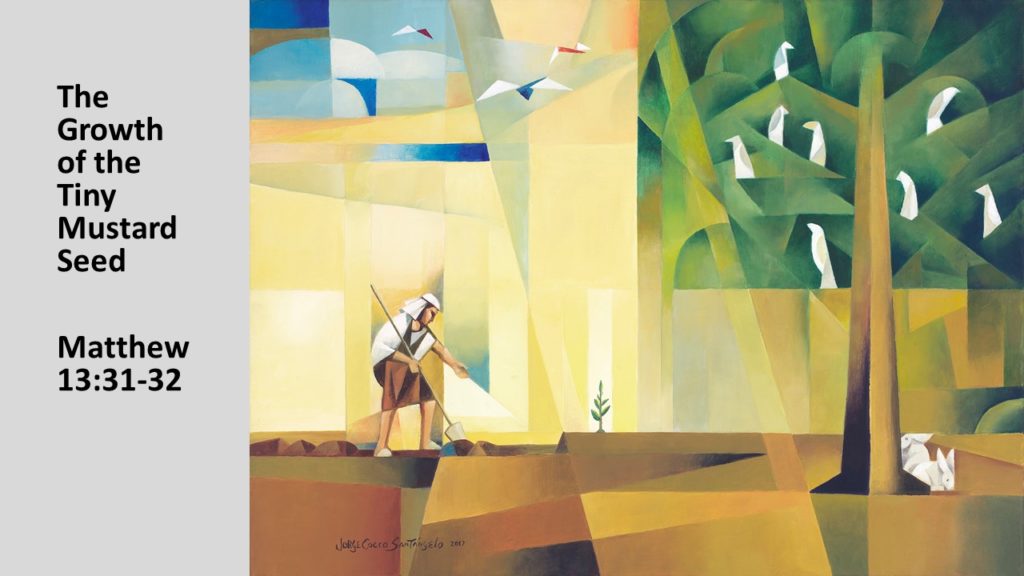

Jeannie: Next, in Matthew 13, comes the parable of the mustard seed, which teaches the principle of growth and progression.

As this painting sequentially illustrates, in three stages from left to right, a tiny seed – carefully planted and tended – will grow to a large mustard plant (which Cocco has taken the liberty to present as a real tree), where it will become home to the purified birds of heaven. Joseph Smith saw in this parable an antidote to the apostasy, with the Book of Mormon being that seed that will come up out of the ground, and to give rise to the restored church that will safely harbor the birds that chose to build their nests – or, in the Greek, literally to “tabernacle” – in its branches. Isn’t that a wonderful concept – to build their tabernacle there, in its safe branches!

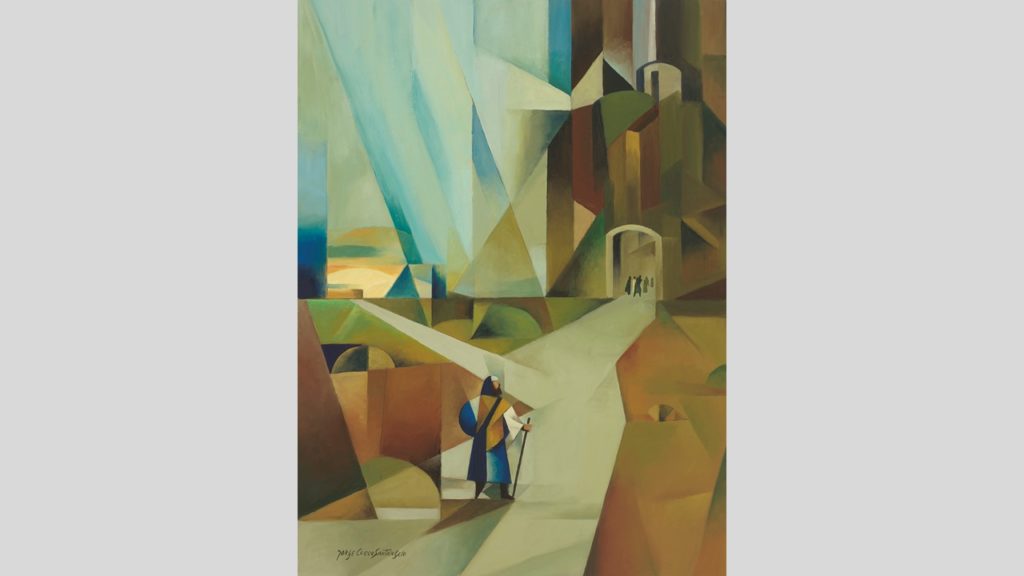

Jack: And so it is that the Plan requires each individual to choose; meaningful individual choice, coupled with consequences and accountability, is the enabling power that makes life in this mortal existence eternally valuable. Thus, there will be two ways, two gates, two foundations; for there must needs be an opposition in all things. Cocco’s geometric design always makes the crux of the parable the commanding focal point of the composition.

Here, the absolute center of this painting is this parting of the two ways – and, as you see, our traveler’s head is positioned precisely at that critical point of departure.

The Plan of Salvation next makes it clear that consequences and accountability will follow our wise – or short-sighted – choices. Cocco studiously infuses specific textural details into his images, as the artistic comments accompanying each parable in our book make clear.

In this case, Cocco’s painting exaggerates the strength of the templed house built upon the perfectly flat and solid rock; while, in counterpoint, he emphasizes the force of the storm and the magnitude of the collapse of the house built upon the unstable foundation.

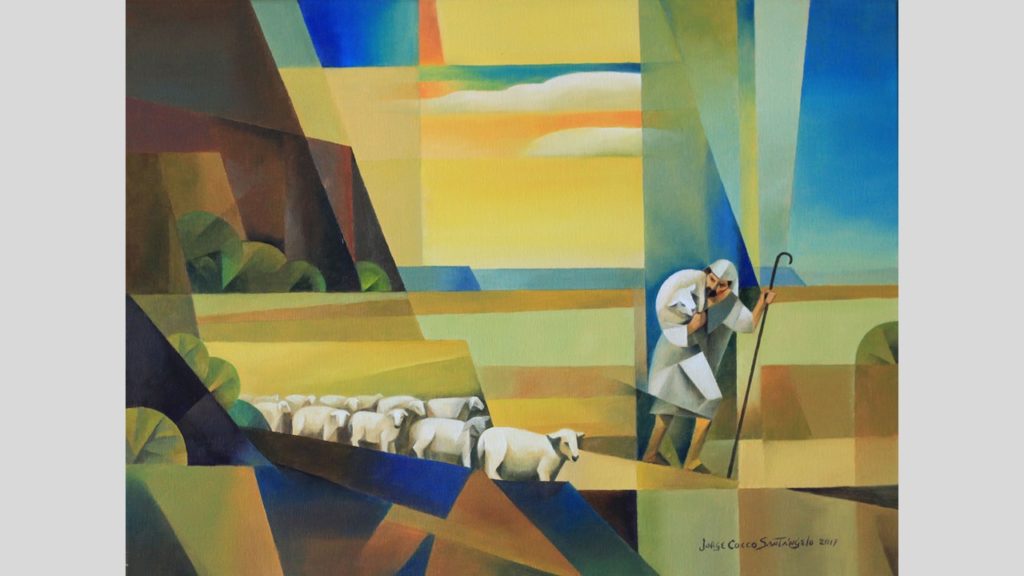

Jeannie: The several “shepherd” parables vividly illustrate the concept that those who choose the covenant path can trust in the protection of the Lord, who presents Himself as the Good Shepherd who calls to His sheep, who cares for them, and who goes after those who go astray.

In these parables, he emphasizes His role as one who protects, who carries, who leads the sheep of His fold. Most of all, we see vividly how He sincerely loves His sheep. The symbol of sheep is powerful for a reader who understands that sheep are among the earth’s most vulnerable animals: they have virtually no means of self-protection. They need a shepherd’s care, and they also need one another. The only security they have comes from being close to the shepherd, and being a member of a flock. As was promised in the premortal Council, our Shepherd, Jesus Christ, will eventually give His life to enable all to remain in His fold, and to rescue all who heed His call and follow Him.

The shepherd parables also dramatically portray for us the unimaginably great joy that takes place in heaven when each one who is lost is brought back to the fold.

That joy is shared among family and friends; for the song of redeeming love, according to Joseph Smith, is not a solo; heaven is other people! Heaven is blessed with celestial sociality; that is the essence of eternal life with Christ and our vast, heavenly family.

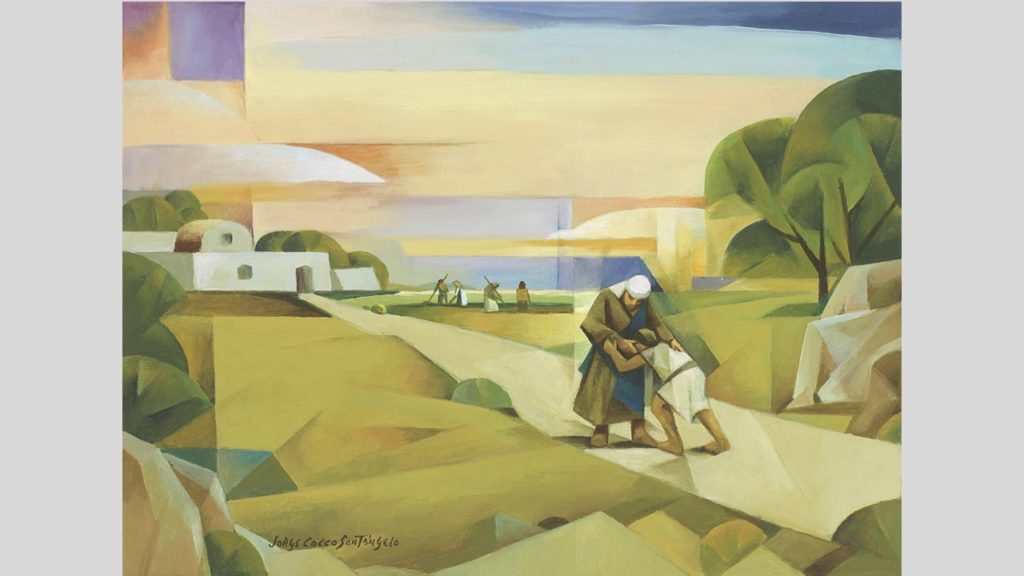

Jack: But, unlike the lost coin and the lost sheep – who do nothing to become found – humans who have wandered off must come to their senses, repent, and return of their own free will, while the Father watches for their return, and celebrates their homecoming.

Cocco’s portrayal beautifully captures the essence of the many steps in this process: of repentance, forgiveness, celebrating, and picking up and starting over – as taught by the parable of the prodigal son.

But, once we have been forgiven much, the Plan requires that we too, in turn, must forgive, consecrate, and endure to the end. The Lord’s prayer pleads: “Forgive us our trespasses, as [that is, to the same extent that] we have forgiven others who trespass against us. And here we have the next parable – that of the unforgiving servant – who was forgiven a huge obligation, but goes right out and turns around and refuses to forgive one who owed him a significant, but comparatively very small, amount.

Notice how deftly Cocco reverses the image of the forgiven man on the left, who in turn goes out, does a “180,” and refuses to forgive – giving us an unforgettable image of the terrible offence to God we must strive to avoid.

Jeannie: Other parables then teach that we must endure to the end by persisting in imploring the Lord to answer our prayers and petitions, as Jesus taught in the parable of the importuning widow.

Cocco’s style – which he calls “sacro-cubism,” with its moderate geometric abstraction – portrays only the most obviously recognizable elements of the story; and this pairs really well with the literary style of the parables, which offers a complete story but told only with the most essential details. This universalist approach allows all readers everywhere, at any time, to understand the narrative as seen in their own particular contexts. Thus, Cocco’s renditions are both timeless and without geographic specificity, as are our Savior’s enduring parables.

The next parable we discuss comes with a warning: we must be prepared to strive to pay a heavy price.

In the parable of the pearl of great price, Jesus situates us just like a merchant, who finds a pearl of great price for sale, and willingly sells all that he or she has to buy and treasure it. In Matthew 13, the need for consecration is the next-to-last step in this series before the final parable of judgement.

Jack: In no case does Jesus write himself more unmistakably into his parables than in the case of the parable of the wicked tenants, which teaches most plainly the mystery of the death of Jesus. The wicked tenants beat and abused the absentee landlord’s servants, and, in the end, will even kill his son. Even the chief priests were smart enough to understand the point of this one: that Jesus spoke of them, and of Himself.

Of this drawing in the book, we said: the dying, or dead, householder’s son is not shown racked with pain and suffering as is often the case with artistic portrayals of the agony and passion of Jesus. Here He is, stretched out, with both arms extended above His head: His final, forsaken gesture. His face is in the dust, returning, as it were, and atoning for the fall of Adam, who was of the dust. The stylized thorn bush, faintly looming in the right forehand corner, is a portent of the crown that will be placed upon his head by the mockers prior to His crucifixion. His Atonement is a free gift to all of His children. When I asked Cocco if he planned to paint this sketch in oil, he said “No, I can’t do any more with this one; it’s too painful.”

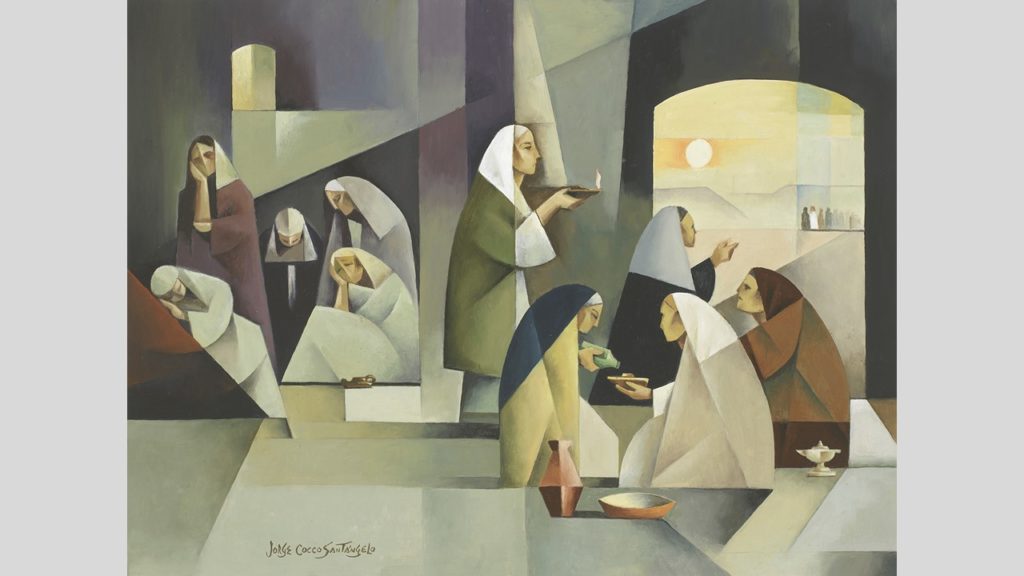

Jeannie: And that gives you just a little measure of the immense sensitivity of this dear, dear man. Of course, just as there are just as many ways to appreciate art, there are many ways, or levels, to read the parables: some offer multiple levels of meaning – cultural, ethical, or symbolic – as seen, for example, in the parable of the ten bridesmaids.

Reading it culturally, it helps the reader to understand the details of the Jewish wedding customs at the time of Jesus. For example, the Bridegroom was delayed because he was negotiating the terms of the marriage with the bride’s father. If you think of this ethically, it helps to see more clearly that each bridesmaid needed to come prepared with the oil that her own lamp would require. As President Kimball explained to us: “Those who brought extra oil were not able to share their light of faith – or the cumulative effect of a life of righteousness” [Faith Precedes the Miracle]. Symbolically, this reminds us that certain things, like personal testimonies cannot be shared. We cannot live on borrowed light – or borrowed oil. Seen Christologically, this parable unforgettably illustrates the Plan of Salvation’s promise – that the Lord Jesus Christ will eventually return for His marriage and Messianic reign.

Jack: Just as the day of Judgement will follow the Millennial reign, several parables next describe various phases of God’s Judgement – which will separate, purge, select, preserve, honor covenantal promises, and reward. For example, the first stage of separation and purging is depicted by the time of harvest in the parable of the wheat and the tares.

Second, a process of selection and preservation is taught in the parable of the great net of the fisher.

Just as these parables speak and apply to all people, Cocco’s art is universally accessible, and applicable as well. We find that our grandchildren – to whom this book is dedicated – are particularly drawn into these portrayals.

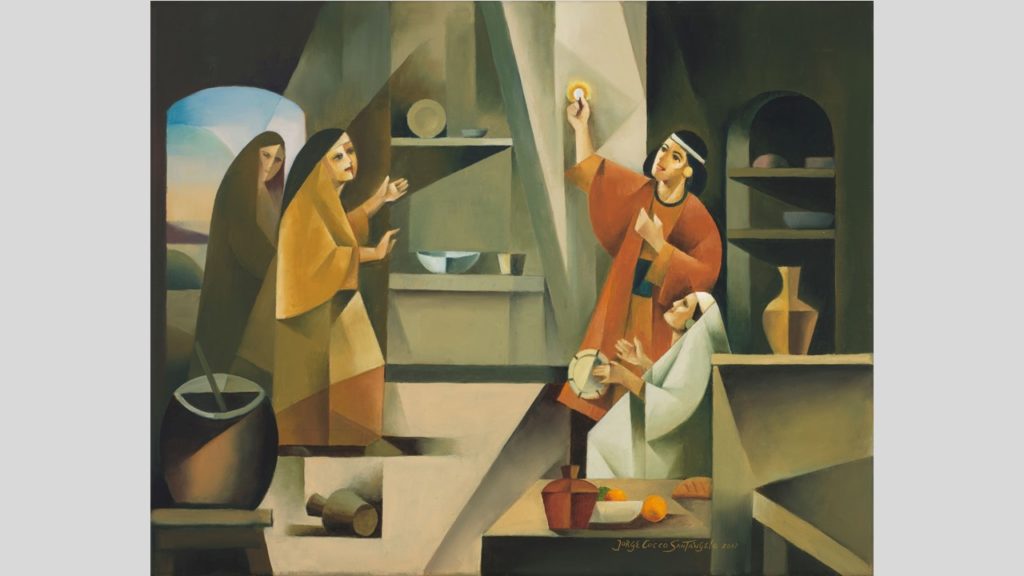

Jeannie: And the final judgement parable – that of the talents – we have the story of certain investment managers who are entrusted with large sums of silver, or gold, to manage for their masters.

Here, especially – but in all of Jesus’ parables – we are invited to ask “Who am I in this parable – am I the one neglecting my possibilities? Or am I more like the ones who are working to develop the vast resources that belong to the Lord, but which are entrusted to His stewards? Significantly, the reward given in the parable of the talents is not to keep the profits generated, but the servant is instead allowed to hear “Well done, thou good and faithful servant; enter thou into the joy of the Lord, who will make you ruler over many things.”

Jack: As all parables aim to inspire and demand action, Cocco’s portrayals likewise typically show action, movement, growth, development – helping us to progress in becoming true disciples of Jesus Christ. And thus we see how Jesus teaches the Plan of Salvation in His parables. Due to the plain and precious truths restored by the Book of Mormon, Latter-Day-Saint readers and commentators have so much the advantage in unveiling the mystery of the kingdom of heaven that Jesus taught to those who were ready to receive.

These canvases act as a guide, drawing us in and helping us direct our personal introspection and development. The parables of Jesus help us ask “What lack I yet? Lord, what would you have me do?” Jesus said, to the rich young ruler: “Put the Lord first, and come follow me, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven”; and, as the Father has said, “This is my work and my glory: to bring to pass [step by step] the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:39).

While His parables were presented in no particular order – but, instead, as circumstances and questions arose – in the end, they all together teach the way of the life of righteousness as a full and coherent whole.

Jeannie: People also may wonder: why did Jesus tell so many parables? The answer may be precisely because there are so many doctrines in the Father’s great Plan. All of these doctrines are needed, and all of them need each other. As Elder Maxwell has said:

If focused upon singly and exclusively, the doctrines of Christ are so powerful, we can spin off, and go wild. Orthodoxy, therefore, rather than being repressive, is a grand adventure in handling powerful doctrines that bring great happiness when fitly framed and woven together, but which can bring misery if we spin them off separately.

The doctrines of the church need each other as much as the people of the church need each other. We dare not break the doctrines apart or specialize within them, because we need them all to achieve spiritual symmetry – an outcome that requires connections and corrections. (Whom the Lord Loveth, 159-60)

It is our hope that Cocco’s paintings, and our writings, will fitly frame all the sacred principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ jointly, collectively, and covenantally – that we may all, as members of the body of Christ, achieve together our eternal goals, in our divinely appointed and talented roles. Of these things we bear testimony, in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Q&A

Jeannie: Where, besides Chartres, are significant collections of stained-glass parable imagery? Well, there are parables in many of the cathedrals in France – of course, we’ve been to France many times for me, the French teacher, so we’ve looked at a lot of them. The three that have the vivid Good Samaritan parables that portray this understanding of Christ being the Samaritan can be found at Chartres, Bourges, and Sens. Many of the cathedrals have the prodigal son, and other parables, but we have focused and taken pictures of just these three cathedrals for the Good Samaritan – although there are many other parables portrayed in a variety of cathedrals, of which there are many in France.

Jack: Yes, and in the Chartres cathedral there is also a wonderful, but rarely seen, long series of the parable of the prodigal son. It’s right at the crux of the cathedral, and it’s up high – and the light is such that it is often very difficult to notice that it’s there. We were there when the light was perfect, the last time, and they had just cleaned it – but it’s another sequence; it has about twenty-four scenes in the parable of the prodigal son. That window is looking at the high altar, and the son, who of course is repenting and returning, is hoping for forgiveness. And the son who stays out in the field complains that there has never been a fatted calf for him. Well, the word for “fatted calf” there is the same word that is used for the “scapegoat,” or the sacrificial animal. The one in the field realizes, if he represents Jesus, there will be no sacrifice for him, and he will therefore be a part of this forgiveness that will be possible to the son that has come back. But that window is looking up at the high altar where the position, I think, is not accidental. Nothing in these cathedrals was simply accidentally put where they are.

One question that was just asked is: “Is the parable of the prodigal son an example of the ancient teaching of the doctrine of the “two ways”?”; and the answer is: sure! – just as the other parable of the two sons (the willing and unwilling two sons) shows the two ways, and who actually stands at the root of each of those two ways. The parable of the prodigal son has been interpreted in many ways, and in our book we go through a range of possibilities. Coming out soon, in a [?], I have a very long article about interpreting the parable of the prodigal son. It is wonderful how rich the parable is, with all kinds of possible meanings. We see it in Luke, chapter 15, as a part of the three parables that Luke puts together: the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son. All are dealing with this stage of repentance: that if we are going to be able to really make full use of the atonement of Jesus Christ, we must repent – and I think Jesus taught that principle over and over again.

I don’t like to get hung up with whether the older son is a pharisee, or the younger son; who are these people? Who is Jesus actually thinking of when He tells these parables? Joseph Smith encouraged people not to try to read this parable that way. I think the eternal doctrine is more powerful than the cultural moment that might have been involved in what Jesus said. But, more than that, Jesus is giving this parable during His ministry. It is before His death; He knows what will happen to Him, and the price that He will pay; and remember that that parable of the prodigal son ends with the Father saying: “Everything that I have is yours; you have been with me always.” So there is a heavy Christological image in the son, who is the older son who stays home there as well. These parables are multivalent; you can use them in many ways, and that is one of the reasons we enjoyed working so much with Cocco’s geometric interpretation. What he has given us here are timeless; they are not culturally situated; they fit with all people, and I think that’s how Jesus would like them to be understood.

Jeannie: And they are also not grounded in too much materiality. You can truly see the spiritual essence of what the Savior is trying to convey. He is using material things to convey spiritual ideas. And I think Cocco is able, somehow, to transcend, to present those very ideas – to take us out of the material and into the spiritual, and that’s why we love them.

They ask if we have a parable of our own; we won’t share it, but yes, in our family we have many silly parables that have guided our lives throughout.

Jack: I want to know what you think. What’s your answer to that question? I didn’t know.

Jeannie: I would say there are two major ones; I once said, in my dating days, to a person who I was speaking with; we were drinking Kool-Aid that had been made up in the Welch’s grape juice jar, and I said: “no, this relationship doesn’t work; it looks purple; it is sweet, but it’s not the real thing. I’m looking for the real Welch’s grape juice in my life.” And I found him, did I not?

___________

[Lightly edited for clarity and readability]