August 2018

I am very grateful for the opportunity to talk about my very favorite subject. Although I’ve studied Mormonism in India extensively, I approach the opportunity to speak about Indian Latter-Day Saint women with some trepidation. I’m not of Indian descent, and I can’t even claim to have served a mission in India. Furthermore I acknowledge I speak from a place of privilege. I’ve had the opportunity to visit India several times and personally interview and observe numerous Indian members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. However my goal today is not to speak for Mormon women in India or for Mormon women that are Indian in the Diaspora. My objective rather is to model how we can better listen to and understand Mormon women from contexts very different than our own, and more importantly to model how listening to and understanding Mormon women of the global Church helps us to more clearly see the Savior as He is.

I have been drawn to Mormon’s profound sermon found in Moroni Chapter 7 in preparation for this, and although Mormon’s sermon on faith, hope and charity isn’t addressing Mormon women in India, I find it’s an important resource for understanding and navigating cultural difference as disciples of Christ. Mormon’s admonition, “Do not judge that which is evil to be of God, or that which is good and of God to be of the devil,” can be read as an anecdote to the evils of cultural imperialism. We think our culture is the only way, and judge the other to be of the devil. Additionally, charity which is bestowed upon true followers of Jesus Christ according to Mormon, and which he encourages us to pray for with all energy of heart, allows us not only to become the sons and daughters of God, but to become like Christ.

Seeing things as they really are, most specifically seeing Christ as he is, has relevance to the way we see each other in an increasingly globalised faith. In other words, if we are becoming like Christ, and thus can see Christ as he is, then it makes sense that we could see each other as we really are. This must also work reciprocally; if we can see Christ and see each other as we truly are, then it will help us to become like Christ. In the midst of national and cultural boundaries that divide us, and we might add, increasing political difference among people within our own national boundaries, it’s crucial to learn how to see each other as we are, and as how Christ sees us and be able to be wise judges as we traverse the straight and narrow path in the midst of cultural darknesses. A key to deepening discipleship is to learn to see more clearly. Learning from others in the global Church allows us to see the way Christ is manifest in their lives, and how others are able to hold to the iron rod in their own unique cultural context.

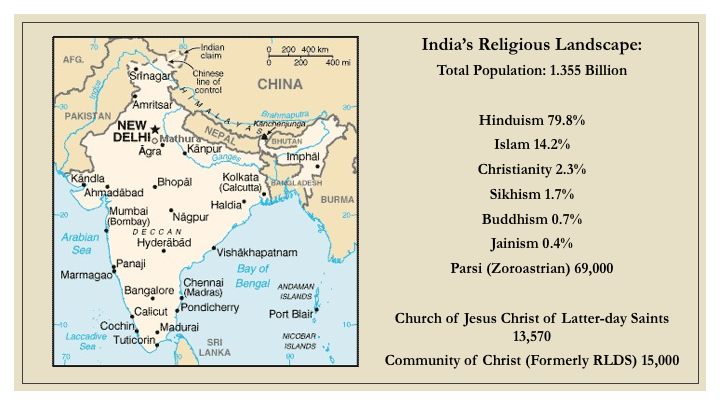

My research in India has brought me into contact with some of the most Christ-like people I have ever met, and not all of them have been LDS. Many of my Hindu, Sikh, and friends from other Christian Churches in India, embody the pure love of Christ and have motivated me to seek understanding of the religions of India and the ways these traditions have shaped Indian culture. Here are some numbers for those of you who like numbers. This is just a glimpse at the 1.355 billion people in India and that’s growing. You can Google this and see this growing; it’s going to beat China soon as the most populous nation on the earth. You can see the divisions of the different religious traditions that were born in India and how strong they are, including the numbers of Latter day Saints there, that now number 13,570 according to the most recent numbers. The Community of Christ (formerly RLDS) actually exceeds the numbers, which is fascinating. There they have just grown in very interesting ways. You’ll have to read the book.

One of my favorite courses that I’ve taught at BYU is world religions. I particularly love to help students appreciate the positive elements in the religious traditions of India. Christians are quick to cry ‘idol worship’ when they look at these traditions, but I think we dismiss thousands of years of God trying to communicate with people he loves when we do that. I think it’s more helpful to look at how leaders and things were inspired; particularly the Bhagavad Gita has a moment in it that is so like the Book of Moses, it’s stunning. And I think we need to be careful, especially because we have members who come from Hindu backgrounds who are bringing spiritual talents that can be appreciated and learned from. Bhakti which is the word for devotion in Hinduism is rampant among Latter-Day Saints in India. They are devoted if nothing else – and there’s much else.

So I would just encourage you to think about, as you’re looking at the other, whether it’s a tradition, a culture, that you remember this part of Moroni 7 where he says, “Behold, that which is of God inviteth and enticeth to [do] good continually.” if it’s inviting and enticing to do good it’s brought forth by the power of God. I think too often we’re really good at being the Church Lady. Anyway we could probably look for the good more often and judge and learn and see Christ more often than we do.

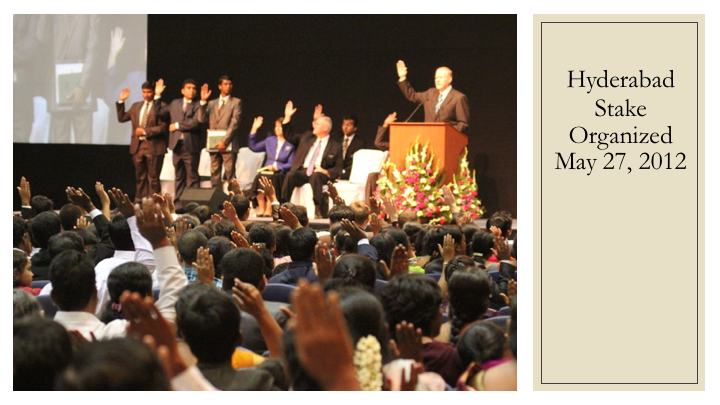

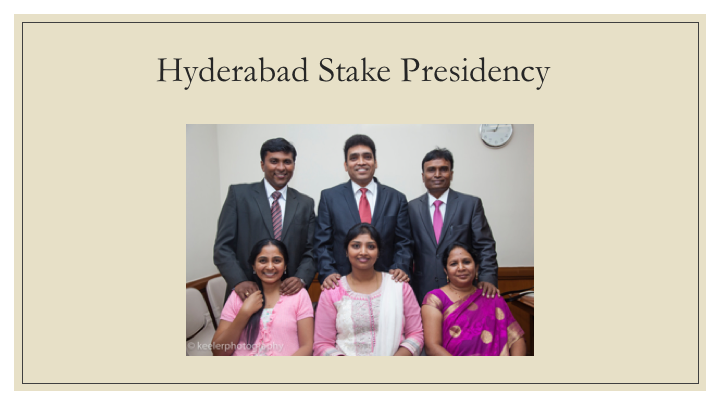

My doctoral dissertation, as well as my current book project, seeks to understand the globalization of Mormonism through the case study of the first LDS stake organized on the Indian subcontinent in Hyderabad, India. That was May 27, 2012, so very recently. Since I started my work, there have been three more stakes added, and President Nelson just announced a temple in Bengaluru, which is very exciting for the growth of the Church there.

I’ve studied both LDS men and women, and that has broadened my understanding of how to live the gospel of Jesus Christ. But as this picture of the choir singing on that day that the stake was organized shows, it’s the women that are special and distinctive in many ways in Indian culture. These women are rocking the sari. Look at how beautiful that is. It’s a beautiful cultural marker, traditional clothing for Indian women. It’s what says India in this picture. I’ve interviewed and observed some amazing men in the Church, but often it’s the narratives of women that I say, “Oh, this was worth the trip just to hear your story, Sister.” I’m excited to share these narratives with you today, and I hope that as I do you can come with me in trying to improve your sight, your vision and seeing Christ in these narratives. I’m reminded by my friend Veena Chinterim who’s here and who I’ll talk about later, that in Asian cultures women are really responsible for the spiritual aspects. They are the keepers of culture and perpetuators of culture. So this is very important to talk about women and to pull in culture as well.

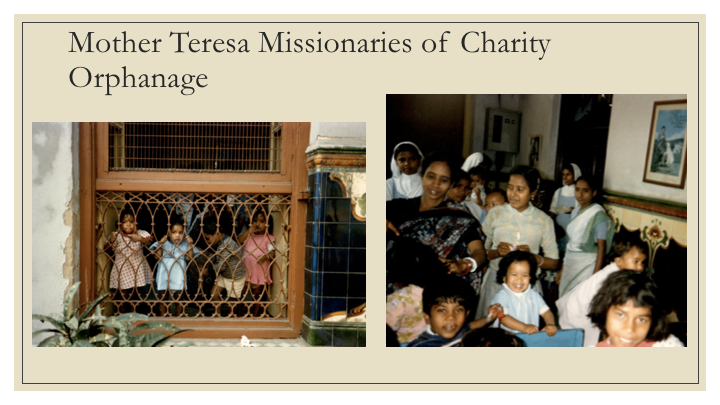

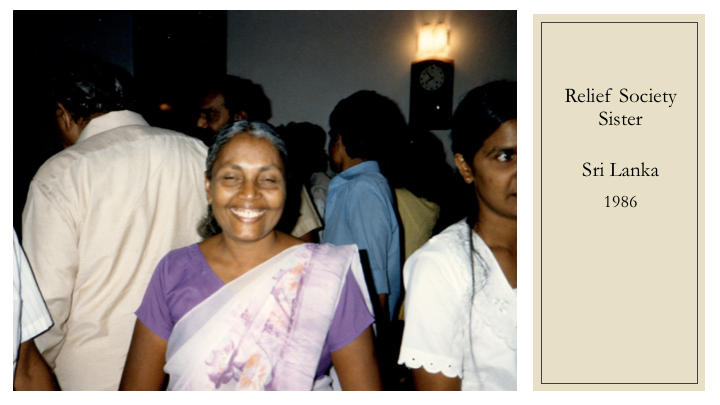

My interest and love for the people of India began when I traveled with the Young Ambassadors to India, Nepal and Sri Lanka in 1986. It was during this trip that I met a woman in Calcutta who was one of the most powerful examples of the pure love of Christ.

Our group spent a day with Mother Teresa and witnessed the way she saw and ministered to the poorest of the poor in the slums of Calcutta. As we accompanied her to her orphanages and homes for the dying, I watched her reach out to everyone she met with the same respect and love regardless of social standing.

I watched her minister that day, and then stood in her private sanctuary in front of her statue of Christ and sang “I Am a Child of God” with the group. I was changed forever. I wanted to see the people of India as she did and serve others as she did, particularly because I’ve been blessed with the restored gospel, and the truth encapsulated in that song. This was actually one of the first times that I’d stepped outside of my Utah shell and understood that Mormons didn’t actually have a monopoly on goodness. That first trip to India planted in my mind the desire to understand how God was at work in the lives of these great people who He so clearly loved and loves, and who love Him so much.

During that same trip I met the first sari-wearing Mormon women. This is the picture of a woman in Sri Lanka. They were serving us a meal. And I remember how exciting it was to see Relief Society women doing Relief Society things, but in saris and without Jello. It was really fun, and very exciting.

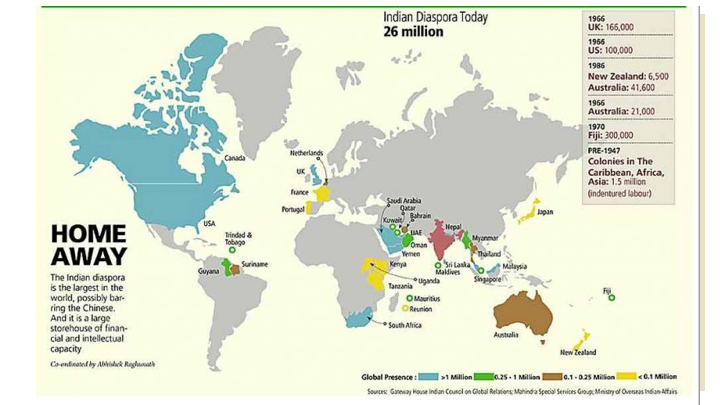

As I talk about Indian LDS women, it’s probably more precise to talk about Mormon women of South Asian descent. I’m just going to give you a little map here.

Many of the cultural characteristics and experience I’ll describe are true of women in countries surrounding India, for instance Sri Lanka, Nepal, Pakistan, as well as women of Indian origin in various countries of the Diaspora, as you can see starting in the British era and as colonial dispersion happened, and it continues today.

Many of us probably have a neighbor or especially with the Silicon Slopes happening, that is of an Indian origin. And so a lot of this will apply to their experience as well. What these women have in common is a cultural heritage that is a source of pride, and a rich tradition that is not easily diluted and from which there is much to learn. I have learned much from the people of India.

I learned a lot about stake building. My dissertation’s focus was looking at, “What does Mormonism look like in the birthplace of the world’s great religions? Is it a world religion? What’s going on?” And I decided to look at the organization of the first stake in Hyderabad, because that’s the first indigenized unit. In other words, we hand over the Church to local leaders, which in a broader Christian tradition would be called indigenization, and it is then a place in the stakes for what’s called inculturation or contextualization, where the people themselves take the gospel and then make it their own in many ways. Correlation and a centralized Church is making a different result, but we’re still seeing that, if any of you have lived in a stake outside, that indigenization and inculturation happens, and you see some difference that’s important and I think that we should look for and appreciate.

This is a picture of the first members of the Hyderabad branch that were baptized all together in 1978. There was a family who moved to Samoa and discovered the Gospel [and]asked President Kimball if the Church could send missionaries to Hyderabad to their family, and they were told that they would be the missionaries, and they were sent and they baptized these members. At the very bottom there is a little boy in a tie there, and I’m going to tell you a story about his wife.

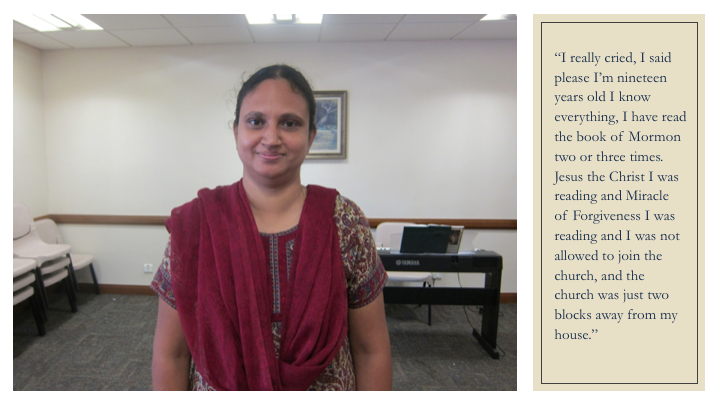

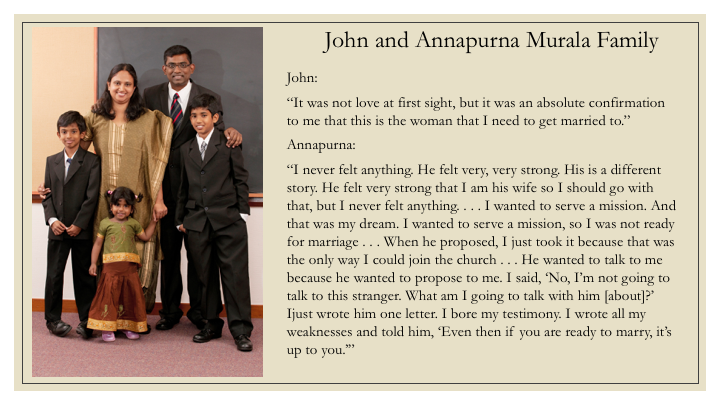

His wife is Annapurna Murala. She was an avid voracious reader. Her brother joined the Church from a Hindu background but she was not allowed to join the Church, to even go to the Church or talk to missionaries. Anything that she did was behind closed doors. But her brother would bring her reading material and she would eat it up. And by the time she had been reading for about seven years she’d probably read more than most of us read in a lifetime. She was so converted to the gospel, and she said that she went to the mission president when she was finally 19 and said, “I can get baptized now”, and the mission president said “It’s not safe for you. I can’t give you permission. You need to have faith that something will happen and it will be fine.” In India the issue of caste is still alive and well. It’s definitely being pushed against in central cities, but in villages and especially when it comes to marriage, you need to marry within your caste, which is called caste endogamy. That’s very important. And so Hindu women, especially in Annapurna’s time, were very limited. If you became a Christian, your chances for marriage were out the door. So she was very watched over. At one point John Murala who we just saw in the picture came to the mission president and said, “I need a wife, but there are no Mormons in India and I really want a member of the Church. What do I do?” And he said, “Well, there’s a woman who can’t join the Church,” and anyway long story short, John meets Annapurna, just a quick meeting at a member’s home and falls deeply in love with her. No, actually, he said, “It was not love at first sight, but it was an absolute confirmation to me that this is the woman that I needed to get married to.” So in that 15 minutes that happened. This is not uncommon in India because arranged marriages are alive and well. There is a sense that you just find a good match and you fall in love and you make it work. It’s a beautiful concept in many ways.

Annapurna, on the other hand said at this short meeting, “I didn’t feel anything. He felt very, very strongly. His is a different story. He felt that I’m his wife, so I should go with that. But I never felt anything – I wanted to serve a mission and that was my dream; I wanted to serve a mission. So I wasn’t ready for marriage. When he proposed I just took it because that was the only way I could join the Church. He wanted to talk to me because he wanted to propose to me. I said, ‘No, I’m not going to talk to this stranger. What am I going to talk with him about?’ I just wrote him one letter. I bore my testimony. I wrote all my weaknesses and told him, ‘Even if you are ready to marry, it’s up to you.’” And basically what happened was Annapurna’s parents caught wind of things and arranged a marriage for her to a Hindu man. And so they felt under pressure enough that they ran away together. So Annapurna runs to northern India and is married, and then eventually joins the Church. But it was a terrible ordeal for her, very difficult for her. John was in medical school, so suddenly she’s married to a stranger in a northern city where she can’t even go to Church. She’s one of my heroes. She’s just powerful. She’s living now in Texas. He’s a world renowned heart surgeon and they just are really strong wonderful members. Here’s a picture of them being sealed in the temple with their first child.

She explained to me that it was a terrible thing that she did to run away. And she loved her parents and she didn’t want to do that. She said, “I was heartbroken, but whatever is said and done, for everybody’s salvation I had to take that step, for my posterity and also for my parents’ posterity, for their ancestors to do their temple work I had to take that step. If not in this life, in the next life they will know why I have done that.” And there were other women that I interviewed, two others who also had a similar story, came from a Hindu background, ran away and were married and they all said the same thing. It was because of their posterity they had to be sealed. They weren’t thinking about themselves. Eventually cute grandkids have allowed families to reconnect, and people have seen positive aspects of the Church. So there are happier stories, but these are examples of how important caste endogamy is.

Because of the value placed on arranged marriage and endogamous marriage, there is also a robust resistance to the LDS custom of dating in the wider Indian culture. The concept of dating is controversial for members of the Church, and their opinions and understanding vary widely. Members explained to me that there is a misunderstanding among Indian Church members of the term ‘date’ because in its Western connotation it infers loose moral standards like those exhibited in American pop culture. Several Church leaders have expressed the importance of dating by emphasizing and teaching the proper way to date based on Gospel culture. According to an official Church pamphlet, For the Strength of Youth, dating expectations for Church members differ quite well from these norms. The section that talks about dating does have a caveat: “in cultures where dating is appropriate”, but there’s more to it than that in India.

One of the biggest surprises for me was how much cultural adaptation of dating and marriage customs I witnessed among members in India. Arranged marriages and strict limits on dating persist in the LDS Church, particularly in more rural areas and among first and second generation members. For the Strength of Youth encourages dating in groups and waiting to start dating to the age of 16, but according to several Church leaders that I interviewed, the age recommendation has been adapted to 19 for Church members in India. This higher age policy for dating in India seems to be agreed upon by members across the subcontinent, without really any central Church direction. Because youth programs at the Church often combine young men and young women in activities that resemble the language from For the Strength of Youth–and here I’m quoting from For the Strength of Youth–it says, “A planned activity that allows a young man and a young woman to get to know each other better is a date, and helps them to learn and practice social skills, develop friendships, have wholesome fun and eventually find an eternal companion.” These programs can seem threatening to some parents who value endogamy. “We don’t associate with members of the opposite sex normally at that age. We prevent that as much as we can.” One 14 year old woman that I interviewed told me that she had been dating for two years, referring to her attendance at Mutual and seminary activities. Many of the married members I interviewed told me that they found their spouses at the Youth Conference or activity. The truth is that these activities do lead to what’s called ‘love marriages’ or ‘love-cum-arranged marriages’, because eventually they’ll get parents on board and it will be arranged. But they often result in unions outside of one’s caste. And this has caused people to leave the Church. The Church has been nicknamed by some outsiders “the lovers’ Church”. Western marriages and dating practices, which tend to be conflated with gospel dating and marriage culture by North American missionaries and leaders, are clearly at odds with notions of caste and culture in India. Several Indian members also refer to the Church’s guidelines on dating and marriage as wise and as an important part of gospel culture.

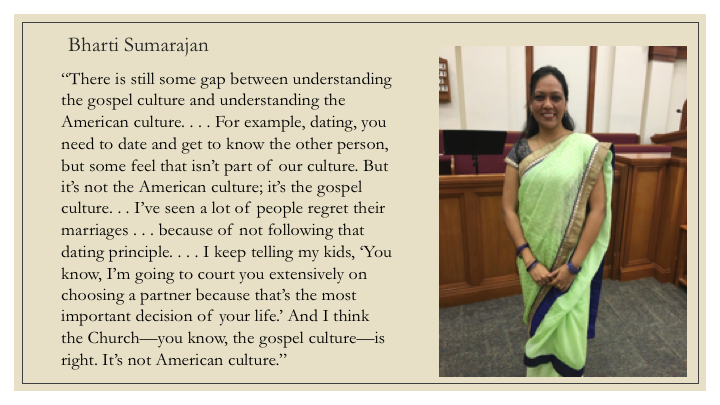

Bharri Sumarajan articulated the differences between various cultural negotiations. Speaking to the question of dating being an American culture versus an Indian culture, she argued, “There is still some gap between understanding the gospel culture and understanding the American culture…. For example, dating, you need to date and get to know the other person. But some feel that isn’t part of our culture. But it’s not the American culture; it’s the gospel culture…. I have seen a lot of people regret their marriages…because of not following that dating principle.”

So a lot of people see this as a principle. I want to just pose that to you: is dating a gospel principle?

She says to her kids, “I’m going to court [counsel] you extensively on choosing a partner because it’s the most important [decision] of your life.” I think even with her determination to let her children decide, she clearly plans to be very involved in defining dating and in helping with the selection of a marriage partner.

A way around this caste versus Church predicament is for LDS parents to arrange marriages, and that actually happens. I interviewed a family whose daughter had just returned from a mission to a Western country and seemed very liberal to me. Afterwards her mother came to me and said, “Shh, it’s a secret. We’ve arranged a marriage for our daughter.” I was like, “Oh, believe me, this girl is not going to go for that.” Well, I returned a year later, and sure enough she was married and had this very happy arranged marriage within the Church. P.S.: arranged marriage is in the Bible.

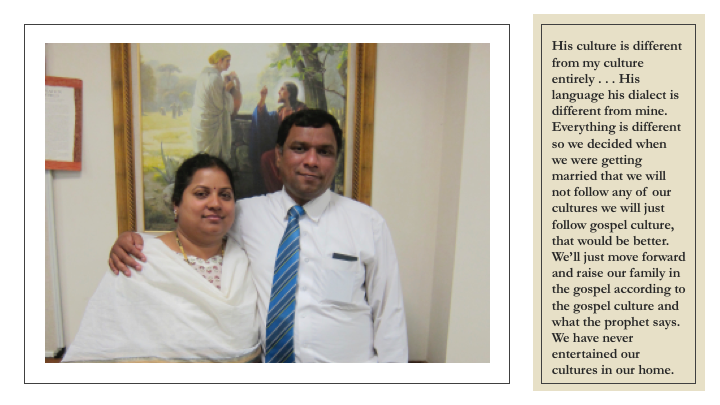

I also wanted to talk about some marriages in the Church between castes. This man said that his in-laws treat him like a bug. He’s like just dirt still to this day, because he’s from a lower caste and she’s from a Hindu background. But it was interesting how they used the term “gospel culture” as a resource. I think sometimes we give gospel culture a bad rap, but there was definitely an attempt by these couples. She said, “His culture is different from my culture entirely – his language, his dialect is different from mine. Everything is different, so we decided when we were getting married that we would not follow any of our cultures. We will just follow gospel culture; that would be better. We’ll just move forward and raise our family in the gospel according to the gospel culture and what the prophet says. We have never entertained culture in our home.”

So the conflict with Mormon culture and caste endogamy, arranged marriage, resistance to dating is complicated by the idea of individualism versus communalism. We take for granted, after the Enlightenment, that we are supposed to be individuals and free, and yet in many of these Asian cultures it is the community that is important. It’s the family that’s important, and joint families are very common, where the parents say, “Why would I need to save or have any worry about that? My children are my savings account. I’m giving them everything and I’m going to live with them and they’re going to take care of me.” So we take for granted some things that are very much a Western mindset that look very different than in other cultures. I saw different preferences for that and different manifestations, different encouragement from various Church leaders and different ways that it was interpreted.

The William family is an example of a really common way that things happen. As I said, because arranged marriage is such, there’s a tendency to rely on a higher power, someone above us to make those decisions for us, to choose a partner. Elder Robert William is a member of the Quorum of the Seventy. He and his wife were living in a city in South India and his wife, Anne, was one of the first sister missionaries in India. When he came home from his mission, he happened to be in the same ward, and she came seeking one day a blessing from the branch president, and the branch president happened to be associating with Robert at the time and he told Robert, “I don’t feel up for this today. Robert, would you give Anne this blessing?”

Now Robert had been praying and fasting that he would know who to marry. He’d never in a thousand years thought of Anne, but he says as he put his hands on her head, he knew that instant that this was his wife. And later he thought, “I can’t do this; I can’t tell her.” But then the feeling persisted, and he finally pulled her aside and said, “This is how I feel. What do you think? Would you be interested in being married to me?” It literally happens; proposals happen this way because of the lack of dating.

So Anne basically started to cry. She was like, “What did I do? Oh no!” She said that she was overwhelmed and eventually she went home, took a while and decided that he was the one and so they were married. But I often see this Spirit-arranged marriage going on, and I think it’s fascinating. Not always, because there is the back and forth between “Is there the dating way or not?”

By now you’ve seen lots of beautiful women’s clothing. All these colorful things in these pictures. Let’s talk for just a minute about women’s apparel in India because this is all part of the women’s experience.

The bindi dot. This is actually one of my favorite Hollywood stars with the bindi dot. [She] is not a member of the Church. Don’t start the rumor that she’s taking the discussions. The bindi is obviously tied to Hindu ritual. When you go to a Hindu temple and pray, you’ll put turmeric paste on your forehead. It’s very much considered a Hindu thing. By the same token it’s also considered by many to be just a beautiful thing to wear; it’s like fingernail polish. So it’s interesting to watch in the Church those who come from a Christian background will usually say, “Oh, don’t wear the bindi. That’s not OK.” Those who come from a Hindu background are like, “I’m just rocking the bindi. It’s just part of my attire.” I heard one member say, “They’ve convinced the leaders that it’s OK, and it’s not.” Well I just applaud the leaders there. They have been very good at allowing agency and allowing cultural adaptation. The other thing is the sari; these are other ways to dress besides the sari, basically a tunic with pants. It’s very common for women who’ve been to the temple because the sari, the way it covers a woman, there’s a bare midriff often.

Well for us, we think, especially in this culture, don’t show your tummy, [and] freak out about your daughter showing her tummy [indistinct]. But for Indian women that’s not the same thing. So a lot of times there’s adjustments at the sari, extending the sari to make all kinds of things. And negotiations with the sari, where people will go to this more comfortable option. I think it’s fascinating in terms of the cultural negotiation that has to go on because of being a member of the Church.

Caste complexities, all these kinds of things cross lines of class, gender, race in India and complicate things even further. A lot of my study looked at gender in the Indian context among Mormons. Feminist scholars have noted the inequality between men and women and said that it’s one of the most crucial disparities in many societies. And this is particularly so in India.

These are sister missionaries. There are many of them in India and they wear Western attire.

Some of them, at least a couple of years ago when I was following the sisters, on P-day they could wear the sari or the kurta. And I just loved that. There’s really a negotiation between Western culture and the sari because you show more of your skin with Western culture.

Anyway here’s some Primary sisters in the background. I will let you look at them while I talk feminism.

These women say that there’s an inequality between men and women and it’s one of the most crucial disparities in many societies, and this is especially true in India with disparity in female literacy, low ratio of females to males at birth, in other words female infanticide. If you don’t have a boy there is disposing of the child and not caring as much for the female child, although in centers of strength in the cities where the Church is concentrated, this is less so. There’s more of a resistance to this.

Feminism in India has happened in three waves, initially with the British. The British were looking critically at sati, which is widow-burning on the funeral pyre, and all of those kinds of things. So there was a push to reform Hinduism and its response to women. At that point in the 70s there was a second wave of feminism and there were greater legal reforms. They created reserved seats for women in politics. So you’ll see a lot of women engaged in politics. And then third and finally, today there’s much interest in the rights and protection of women.

It was evident as I interviewed both men and women in the Hyderabad stake that they were very familiar with the language from the women’s movement in India. The majority of the LDS members that I interviewed in India used the word “patriarchy” in a pejorative, very negative manner to talk about something they were overcoming. Studies have shown that in India the majority of violence committed against women occurs in the home. According to those I interviewed, violence in the home can occur when anyone, male or female, transgresses against patriarchal authority. The patriarch in a joint family might include an uncle or whoever is responsible to maintain the family honor. Thus both men and women in my LDS sample were attuned to the potential abuse of patriarchy and they saw a distinct difference between the culture of the Church and the surrounding culture in Hyderabad. Even though the all-male priesthood structure the Church could be seen as a patriarchal structure, it was seen as enlightened and based on principles that would overcome problems inherent in the patriarchal system. Patriarchy was never used to refer to leaders of the Church, and priesthood was usually the opposite of patriarchy.

A sister serving as a Relief Society President in one of the Hyderabad wards told me about the verbal, psychological and physical abuse that some sisters face in their own homes, even Church members. She said however that she had observed a strong correlation between Temple and improved conditions for women in the LDS Church. She says that women who have been sealed to their husbands in the temple have happier home lives and seem to be more valued in the family. And you hear a rhetoric of men talking about, “We need women to be saved,” particularly after they have taken Temple endowments.

Several of my interview questions came directly from questions used in the Claremont Mormon women’s oral history project, and many of those questions [were] like “How do you perceive the role of women in the Church?” The majority of women interviewed in the Claremont study were North Americans, usually California/Utah. They almost always had some sort of a strong political response to the question. These U.S. Mormon women either expressed frustration and pain at their second class status because of male-only priesthood in the Church, or they felt the need to speak against claims that they were oppressed. The majority of those I interviewed in India however, saw the Church, even with the all-male priesthood, as empowering women in general. The usual defensiveness against perceived oppression of Mormon women that I noticed in the Claremont interviews was absent in Indian interviews. There was usually a sense of pride in the status of women in the Church, and in the ways women’s lives improved with Church membership.

Although the concept of women serving in leadership positions has not always been a natural fit in Indian culture, Annapurna Gutty (this is a different Annapurna) introduced her narrative when I interviewed her by saying, “I was born into a Brahmin family. Brahmins are very orthodox,” she said. “And if you say Brahmins, they’re like the very top layer of the caste system.” I’m telling you this to emphasize the intersection here of her caste, her gender, in this narrative. She was another who went against her parents’ wishes and actually married, although she didn’t feel compelled to run away. She confronted her father and stood up to his patriarchal authority. And you can see this pattern.

For instance when she was a district Relief Society President she was called and she said the district president came to her and said, “All you have to do is talk in the conference. That’s your job,” she said. “I felt like there was certainly more to this calling than that. And when I took out my handbook and started reading, there was a lot more to it.” So she used this handbook to kind of go above his head and make sure that she was able to work with her calling. She explained that things have changed since then, because they had been trained on how to hold proper councils, have an agenda, read the handbook.

The women come out and speak and their opinions matter. According to Annapurna, it took many, many strong women who have stood their ground and said, “This is in the handbook.” She also qualified that these leaders are good people, but they are just so used to doing it the patriarchal way. Breaking that pattern was difficult. Their ego; they’re not used to listening to women. They’re not used to taking ideas from them. “From there it is change,” she added. She’s also started to be a little more patient with them. But her assertiveness is rather unique. I think we can credit her caste and social status. But what’s not unique is her using the handbook as a tool to invoke power against what is often seen as patriarchal control. So the handbook is a tool of liberation. There were numerous times when LDS women in India spoke about how they use the handbook.

In describing the status of women in the Church, I’m not inferring that all members at all times are completely equal, and that gender is all taken care of there. I just want to emphasize the contrast to the surrounding culture, compared to the perceived higher status of women in the Church and the restraint on patriarchy that both members and non-members identified in the Hyderabad stake. And I see really important parallels between another scholar Elizabeth Brusco who studies Pentecostalism in Colombia, and she says that Pentecostalism is more powerful than feminism, because it actually will empower women. It will help men. It will train and control men to not go out and drink, gamble the money away. She sees more effective measures towards women’s equality with those who turn, and I think we would definitely see the same thing in the LDS Church.

Annapurna is a great example of a concept called contextualization or inculturation, which are real buzzwords for people in mission and Christian missions and Christian Church building all over the world. There are different, new to us. We don’t think about them, but the concept is that the Gospel needs to be contextualized or inculturated in the inner parts of this culture. And they need to take with it and do what they will. We do the same thing in terms of allowing for variations in the handbook, handing over lessons to lay Church members who control the theology every week. We just don’t acknowledge it very much. Former Church President Gordon B. Hinckley gestured toward an openness to the other in encouraging people everywhere to “Bring with you all the good that you have and let us add to it.” And we also had several Church leaders who have said, “Keep all the good and add to it.”

However I would sometimes try to get Hindu converts to talk about their Hinduism, and “What did you bring from your Hinduism that’s good?” But the sacrifice for them was so great, it was really a hard leap for them to look back and say, well *this*. Sometimes it was confusion, sometimes it was horror. But I did find some really interesting examples of inculturation and contextualisation like Annapurna. She would [use] the festivals of various Hindu gods that were in their community and everyone celebrating together. She would take those festivals and teach a gospel message with that about devotion of this person in Hindu mythology. She would use them; they loved the battles in the Ramayana. And so she would take the battles in the Ramayana and she would parallel them with the battles in the book of Mormon and then try to find that little parallel. She was great at that. We do similar things with our pagan symbols in Christmas and Easter. And we’re not too freaked out about it.

Another woman talked about how she continued the ritual of cleaning her home each Friday which is a Hindu practice in anticipation of the worship of the goddess Durga. “But,” she said, “I still do that, but it’s not for Durga, but it’s to create a better atmosphere for my family, because cleanliness is a gospel principle.”

Another interesting contextualization was Mother in Heaven. Because there’s so much goddess worship in India, I thought, “That’s an interesting place for a contextualisation. How do Mormon women deal with Mother in Heaven?” One of my questions was, “What’s your concept of a Mother in Heaven?” And I was met many times, [that reminds me of what Lisa was talking about this morning that there’s this folk doctrine that we don’t talk about Mother in Heaven because she’s too sacred and Heavenly Father wants to protect her] and I would hear that echoed back to me often; or I would hear a husband say, “She doesn’t know about Mother in Heaven; don’t talk about it.” But it was interesting. Many of them did. And Annapurna, the first Annapurna I talked about, when I asked her, she said that the concept of Heavenly Mother was a source of comfort for her. She said, “Though we do not talk about her because it is very sacred, sometimes when I cry, I think of my Heavenly Mother. When I’m very sad, I think about my Heavenly Mother, that I’m keeping my head in her lap and she is caressing me. I know one day I will see her. We will see her.” And that’s an example of contextualisation, of putting the truths and the power of the restored gospel into the hands of another culture, of another human. And that creates beautiful things.

One of the interesting negotiations with culture, because marriage is so important in the culture, family is so important, there’s a lot of adaptation that’s done to continue to include all of the family members who might not be Mormon. They’re still different branches of Christianity; they’re still Hindu. One of the important rituals of a Hindu wedding, [this is a wedding couple that I took a picture of at a Hindu Temple] is they receive these garlands, the wedding couple exchange garlands, kind of similar to the way we exchange rings. And this goes all the way back to the Ramayana when Ram and Sita are married, this whole tradition. It’s interesting because we see some of these replicated in the big marriage celebrations that occur in India.

[These] are two of my favorite students at BYU who also served missions in India, and lived in India for years and years. Anyway they were married. They had several [events]. Weddings in India take a long time, can be very costly, very many days if you experience this. And this continues to happen in the Church. So they had an engagement party in Utah.

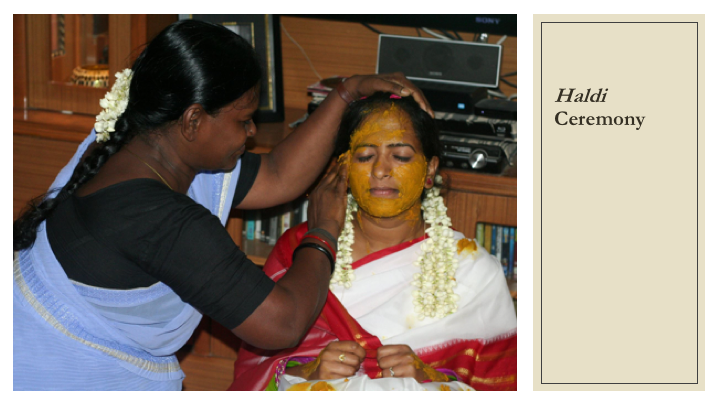

They had what’s called a Haldi ceremony. This is when they spread turmeric on the bride to bring out her glow. And each member that is there will spread and help. It was interesting; her husband who comes from a Hindu background said that there was a little bit of concern when he had his Haldi ceremony, because they put some on his forehead and some of the members said, “No, no, no, that’s Hindu, we can’t do it that way.” And he said, “I just went with the flow; whatever.” There were other Hindus there that needed to have it happen that way. They then were married.

They have to be married civilly first in India before they can be sealed in the temple outside of India. So the marriage ceremony you can see here, the garland ceremony here that they’re doing, it replicates what I saw in the Hindu temple, the tali, the tying the knot. All of these things are replicated in these ceremonies within the LDS Church that occur, very common for them.

This young woman chose to wear a white sari.

They had receptions; they came home and had a reception for their Lutheran friends and family members, and had a Lutheran minister say some things, and so I saw because of this ability to marry in the temple outside, there was a multiplication of marriage ceremonies and things that they could do, that were included and were accepted in the culture, kind of similar to the way we do a ring ceremony.

Then they were sealed in the Hong Kong Temple.

This is Veena Chinterim, who’s back there; you’ll get to know her, she’s amazing. She is from Mauritius, so her ancestors were taken there as indentured servants with the British Empire to work in the sugar industry. But the population of Indians is the majority in Mauritius and they’re very proud of their cultural heritage. When Veena was married, she made sure that she was able to wear a white sari and she went to her stake president and explained why this was important, showed pictures of her parents and wanted to make sure that everyone was okay that she was going to do this. And of course she looks amazing. It’s just gorgeous. Here’s a picture of her Haldi ceremony and her bridesmaids in saris as well.

She comes to this from her father who just passed away last week. Her father was a very important leader in the Catholic Church in India. He saw members of the Catholic Church that were Indian, who needed to connect to their Hindu roots or their Indian roots.

The tricky thing here, people, is where does religion end and culture start? It’s really difficult to define that barrier in Indian culture. So what Veena’s father did was to encourage aspects of Indian culture within his Catholic faith, so they would have a Diwali ceremony and they would tie this to the Light of the World, to Christ. Her mom was the choir conductor in the choir in the Catholic Church and she would make sure that the hymns were translated into Tamil and French, and all the different languages, but they had that beautiful tonality that was very characteristic of Indian song.

And Veena has done the same thing in her own Mormon culture. This is her family home evening Diwali practice, that wherever she lives she’ll invite people over. She’ll help her children connect to the fact that this is a celebration of lights, and this we can relate this to the celebration of Christ. She does a beautiful job of doing this. It’s not easy. It’s easier when everyone is doing the same thing in your country. But in Diaspora and in a ward in Utah, for instance, it might be a little more difficult to be you and to rock whatever your culture is. And Veena does a beautiful job of that.

Here’s a picture of her children.

That’s a picture of Veena, her mother and her brother at her father’s funeral and her mother sang this to me just last week when we were eating lunch with her father. And it was a beautiful Christian hymn, and I wish you could hear because it just had these tones that are so different than what we hear on Sunday, and with the new hymn book coming out, I’m hoping that we have some different things going on because it’s important. The reason I do this work and I feel this is so important is because this is part of the globalization of the Church.

A globalized Church, there’s no center and margin. It’s all one, and we learn from each other and we give to one another and we reciprocate. And it’s crucial within our own wards and communities that we navigate the differences in culture.

This is one of my favorite quotes that was off the record for a General Authority, so I’m not going to quote him. He said the culture is very much not just outside in some far off land. It’s very much here. We very much deal with that. He said all of us inherit a culture that is manmade and it is very difficult to see the filters that culture places on us because we’re born into it. We’re swimming in culture. We don’t notice it and thus it is hard to break beyond it. You need revelation to break beyond the boundaries of one’s own culture. Some people work harder to get that revelation than others, he said. And when that revelation occurs, the mists of darkness begin to part and you can make your way down the pathway of life. I love that.

And back to Moroni 7. The spirit of discernment is so important; the spirit of charity. All of these things help us to discern and to navigate culture and to love one another and to see Christ in each other.

I love President Nelson’s words from the last conference. He said, “I urge you to stretch beyond your current spiritual ability to receive personal revelation”, and I would encourage that in this realm of navigating the difference, that you receive revelation to guide you and to help others on this path.

He quotes Neal A. Maxwell in this talk who said, “To those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, it is clear that the Father and the Son are giving away the secrets of the universe.” I testify that our Father in Heaven loves all of his children. He loves our beautiful differences. We need to love them and learn from them, and I say this in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Q&A

Q 1: Would you say more Hindus or Muslims are joining the Church in India?

A 1: When I first did my study, the numbers of members that I interviewed were mostly Christian. One observer, a critic of the Church, says we’re just poaching from other Christian churches over there. But continuing my second trip over, my interviews reflected more of a Hindu background. I’m seeing more and more of that. Muslims? No, I haven’t seen any of them. And the first mission president, Gurcharan Singh Gill, was a Sikh, a convert to the Church. But primarily you see Hindu and Christian converts to the Church.

Q 2: Are people persecuted for joining the Church?

A 2: Absolutely, violently, dangerously. It’s no joke. We take so much for granted. Absolutely.

Q 3: About 50 years ago when I was in Japan some members there would go to the stake president to help find and arrange a marriage to another LDS person. Arranged marriages aren’t just in South Asia.

A 3: But yeah, definitely.

Q 4: Was bride price a challenge in marriage?

A 4: That’s a great question. So it’s not the same as in Africa. There is dowry and that the leaders of the Church counsel against that. They’re saying, “Take that money; get to the temple.” That’s the counsel. However many of them will interpret this in different ways. If we give this person a gift, it’s not a dowry, it’s a gift. So that kind of exchange will happen. And I see less of people coming down on this in India than I see in Africa.

Q 5: What is the relationship of the LDS Church to Indian institutions such as Hindu groups, government officials, social welfare organizations, schools, et cetera?

A 5: It’s a great question that I have not enough time to answer, but I will say that there is growing Hindu nationalism in India, very similar to growing nationalism here. The Church is very sensitive to that, very careful and very committed to serving and working with other social organizations. The humanitarian arm of the Church has lots of connections; they work with people in India and do some great things.