[Download PowerPoint Presentation (PDF) (pdf)]

Thank you, Laura, and thank you for inviting me to FairMormon.

I’ve been doing research on this latest book for the last seven years. I’ve grown accustomed to the blank stares and suspicious looks, especially when I tell people the subtitle of the book, “Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness.” People are naturally skeptical, and we just have to look around the room here at FairMormon and see a bunch of white people — what struggle did Mormons ever have to do to claim their whiteness? I welcome the skepticism and I hope you’re skeptical enough to actually read the book.

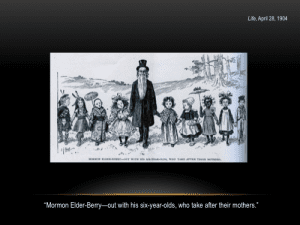

Let me just begin by talking you through the political cartoon that I chose for the cover of the book. This was published in Life Magazine on April 28, 1904, simply titled “Mormon Elder-Berry–out with his six-year-olds, who take after their mothers.” So in this Life Magazine 1904, there is no commentary, just the picture itself and then the title that goes along with it.

In the state of Utah at least two of these marriages would have been illegal. And in several other states, three of the marriages would have been illegal. What I think Life Magazine is suggesting is that polygamy is not just destroying the traditional family, it’s just destroying the white race. And I see this political cartoon as a moment of transition for Mormonism. Mormonism is attempting to claim a white and pure future for itself at the same time that Life Magazine is attempting to trap it in a racially suspect past.

Those of you who are historians in the audience will know what else is going on in Mormonism at this moment. Joseph F. Smith, the President of the LDS Church, has just returned from a withering six days on the Senate committee witness stand in the Reed Smoot hearings. He has returned to Salt Lake City, and on the sixth of April 1904 issues what historians refer to as the “Second Manifesto.” He tells the LDS faithful — We really mean it this time. We really are giving up polygamy, and if you take additional plural wives, you’ll be subject to LDS excommunication. — And that’s the policy the LDS Church follows to the present.

You have to understand that in the 19th century, marriage was racialized. Monogamy was white and polygamy was branded as “not-white” or the preserve of the Asiatic or African peoples. And so one of the ways in which Mormonism is claiming whiteness for itself is by transitioning from polygamy to monogamy.

I chose this political cartoon for the cover of the book, and then Mormon Elder-Berry’s fictional family becomes the organizational tool for the book. As in most families not all children get equal treatment. The six white children get one chapter, the Native American child gets two chapters, the African American child gets four chapters, and the Asian child gets one chapter.

Let me give you at least a couple of theoretical big-picture ideas to keep in mind, and then I’ll walk you through some the evidence. I argue in the book that it is only in viewing Mormon whiteness as a contested variable, not an assumed fact, that a new paradigm emerges for understanding the Mormon racial story.

I know everyone is skeptical. Mormons were mostly white in the 19th century, and I am not suggesting otherwise. But one way in which outsiders suggested that Mormons didn’t fit in – they weren’t just religiously suspect, they were racially suspect. They are more like or similar to African Americans or Native Americans than they are to white people. This is one way you could justify discriminatory policies against them. So you have to divorce yourself from 21st-century notions or thoughts that race is a biological fact. It’s a social construct. You have to recover 19th-century notions of race. They are very fluid. They are illogical. Irish immigrants are racialized as similar to African Americans. And Mormons go through the same sort of process. And I’ll give you evidence – I still see a lot of skeptical stares.

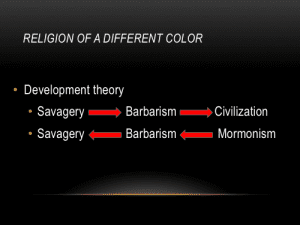

The other big-picture idea that you have to keep in mind is the development theory that operated in the 19th century. Thinkers in the 19th century believed that all societies progress through three basic stages – from savagery to barbarism and from barbarism to civilization. And as they do so, they abandon adherence to despotic rule and polygamy. Anglo-Saxons were cited as the best example of this. They had abandoned adherence to kings, and they were the preservers of liberty and freedom, and they also had abandoned polygamy.

The fearful thing with the Mormons then was that “supposedly” white people out there in the Great Basin are giving over their free will to the despots, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, as well as practicing polygamy. So we have this regression along these lines. It’s the Republican Party, remember, who calls polygamy one of the twin relics of barbarism. This comes out of a much broader context. Really what’s at stake in the minds of outsiders is this Republican experiment. American democracy is at stake because the argument was that when you look around the globe only white people practice democracy. Senator John C. Calhoun says that democracy is the government of the white race, on the floor of the United States Senate in 1848. And yet here you have “supposedly” white people in the Great Basin practicing democracy and giving their will over to despots. So we have a deterioration away from civilization and back into barbarism and even into savagery. Sometimes the Mormons are more savage than the savages is the argument. So that’s another big-picture idea to keep in mind.

And then the third big-picture idea is simply that race is something both ascribed from without and aspired to from within. That’s the struggle part that I’ll talk to you about. I will give you evidence now from the book that will help you to wrap your minds around what I’m talking about. So you have outsiders who are projecting or ascribing an identity onto the Mormons, suggesting that they are less white, and Mormons from the inside aspiring to whiteness.

One way in which you claim whiteness for yourself in the 19th century is in distance from blackness. We see Mormons then across the course of the 19th century distancing themselves from their own black converts.

RACE AS ASCRIBED FROM THE OUTSIDE

Dr. Roberts Bartholow was a medical doctor sent west with Johnson’s army in 1857. He files a report with the United State Senate in 1860. In this report he describes the Mormons that he has observed over the past couple of years. He says, “The Mormon, of all human animals now walking this globe, is the most curious in every relation.” Mormonism is a great social blunder, he argues, which seriously affected “the physical stamina and mental health” of its adherents.

Polygamy, in his mind, was the central issue. It created a “preponderance of female births” because one man is paired with multiple women. He argues that you are going to have more female children than male children. He says it produces a high infant mortality rate. And he says it also produces “a striking uniformity of facial expression,” which included “albuminous and gelatinous types of constitution” and “physical conformation” among “the younger portion” of Mormons. It gets better. He said that polygamy forced Mormons to unduly interfere with the normal development of adolescents and was, in sum, “a violation of natural law.” Mormon men were constantly seeking “young virgins, [so] that notwithstanding the preponderance of the female population, a large percentage of the younger men remain unmarried.” Girls were married to the waiting patriarchs “at the earliest manifestations of puberty,” he wrote, and when that was not soon enough, Mormons made use of “means” to “hasten the period.” It doesn’t specify what magical means the Mormons had discovered, but nonetheless, this is his argument. He also argues that the progeny of the “peculiar institution” demonstrated its “most deplorable effects” in “the genital weakness of the boys and young men.” I have no idea the kind of research the good doctor is about, but nonetheless, this is his argument. Polygamy created a “sexual debility” in the next generation of Mormon men, largely because their “sexual desires are stimulated to an unnatural degree at a very early age, and as female virtue is easy, opportunities are not wanting for their gratification.”

He basically argues that polygamy will solve itself. The next generation of men will go sterile. The problem is that Mormons are so successful at winning converts from overseas that you have this constant influx of new blood into the system that will perpetuate it into the next several generations. But remember, Mormonism becomes a foreign problem. In 1879 the US Secretary of State issues edicts to its consuls in Europe trying to prevent Mormon immigration into the United States. So Dr. Bartholow thinks that if we could cut off immigration the next generation of Mormon boys will be sterile and it will solve itself. All of this, in his mind, will produce the “degraded Mormon body.” In fact, he argues that polygamy is giving rise to a new degraded race in the 19th century: “[A]n expression of countenance and a style of feature, which may be styled the Mormon expression and style; an expression compounded of sensuality, cunning, suspicion, and smirking self-conceit. The yellow, sunken, cadaverous visage; the greenish-colored eyes; the thick protuberant lips; the low forehead; the light, yellowish hair; and the lank angular person, constitute an appearance so characteristic of the new race, the production of polygamy, as to distinguish them at a glance.” “[T]he degradation of the mother,” he says, “follows that of the child, and physical degeneracy is not a remote consequence of moral depravity.”

So moral depravity, in his mind, equals physical degeneracy, and he says you can witness the physical degeneracy in what polygamy is producing in the Great Basin. In this way, race is ascribed from the outside. This is not just a stodgy senate report filed in the United States Senate and forgotten about. It’s picked up by a variety of medical journals and re-published, almost uncritically, both nationally and internationally.

By the end of 1860, there is a conference at the New Orleans Academy of Sciences on the degraded Mormon body and the production of a new race in the Great Basin. All of the doctors who assemble for this conference, except one, buy Bartholow’s argument and even push it forward. The other doctor says – look, Mormonism has only been around for thirty years. It’s too early to suggest that a new race is actually arising in the Great Basin. We should come up with a systematic and scientifically verifiable method to study this new race and wait at least another thirty years before we suggest that, in fact, a new race is emerging.

So you have, then, outsiders who are suggesting there is a degraded Mormon body as a part of this idea that Mormonism is giving rise to a new race. So then, Mormons are certainly aware of this and you have Mormons claiming their own racial identity from within.

RACE AS ASPIRED TO FROM WITHIN

A variety of Mormons across the course of the 19th century demonstrate an awareness of the ways in which their bodies are being denigrated by outsiders and suggest that, in fact, polygamy is giving rise to an angelic, celestial race. It is ordained of God and therefore the product will be angelic, celestial, and divine. Neither side is suggesting that this marital system can’t give rise to a new race, they are just contesting its outcome. “There are no healthier, better developed children than those born in polygamy.” Plural marriage was a principle “established by revelation for the regeneration of mankind,” one Mormon plural wife said. [Mary Jane Tanner, 1880]

George Q. Cannon in 1882 contended that “the children of our system are brighter, stronger, [and] healthier [in] every way than those of the monogamic system.” Other Mormons claimed that plural marriage produced a “more perfect type of manhood, mentally and physically,” and a “fine healthy race.” So you have this contest that is going on over the Mormon body in the 19th century.

How does this impact the racial priesthood and temple restrictions that also develop in the 19th century?

MORMONS CREATED AN INCLUSIVE VISION DURING THE 1830s and 40s

First of all I want to suggest that in the first couple of decades of Mormonism, Mormons created an inclusive vision during the 1830’s and 40’s. We could start by simply citing the Book of Mormon published in 1830. It declares that “all are alike unto God,” including “black and white.” And Mormons have an open vision of who Native Americans are as well. And so they are accepting of people whom broader 19th-century American society suggests should be marginalized and segregated.

W.W. Phelps in July of 1833, “So long as we have no special rule in the Church, as to people of color, let prudence guide.“ [William W. Phelps, “Free People of Color,” The Evening and the Morning Star, July 1833.] He is actually publishing an editorial in the Evening and the Morning Star. Missouri has been established as the gathering spot so — black Mormons, if you come to Missouri be warned. — And he quotes two sections of Missouri’s legal code. You need to have papers verifying your status as freed blacks, and if you don’t, the penalties in Missouri are [that] you will be subject to whipping and expelled from the state.

But Missouri is the gathering place and black Mormons come to Missouri. He says we have no special rule in the Church as to people of color. Yet let prudence guide and the prudence is – be aware of the laws that govern black Latter-day Saints or black people in the state of Missouri. Now this blows up in W.W. Phelps’ face, and becomes the major impetus for the Mormons’ expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri. Remember, the Evening and Morning Star office and this publication were destroyed. His house, as well as the office itself, is leveled. The print is scattered into the street, and then remember, two Mormons are hauled in to the town square and tarred and feathered. And it starts with his editorial, “Free People of Color.”

Missourians believe the Mormons are inviting freed blacks to Missouri to incite a slave rebellion. But not just to incite a slave rebellion, to steal our white wives and daughters, they say. And fear of race mixing is there from the beginning. “All families of the earth… should get redemption… in Christ Jesus,” regardless of “whether they are descendants of Shem, Ham, or Japheth,” Phelps says in another article he writes in the Latter-day Saint Messenger and Advocate. [W.W. Phelps, “The Gospel. No. 5,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger an Advocate, February 1835.] Once again, that Mormons create a very inclusive and open vision in the first couple of decades in terms of who is invited to participate in the gospel message. Remember that most religious people in the 19th century understand race through the Bible and believe that Noah’s three sons, then, explain racial distinction. Shem gives rise to Asians, Ham to Africans, and Japheth to Europeans. That’s how they understood it, and Phelps obviously is a product of his culture, and he’s just simply saying that this gospel message, this Mormon message, is for all people. All people were “one in Christ Jesus… whether it was in Africa, Asia, or Europe,” he says in another article. [W.W. Phelps, “The Ancient Order of Things,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, September 1835.]

Apostle Parley Pratt professes his intent to “preach to all people, kindred, tongues, and nations without any exception” and included “India’s and Afric’s sultry plains” in a poetic expression of his global dream for Mormonism. [Parley P. Pratt, A Voice of Warning, 1837; The Millennium and Other Poems, 1840] Remember, then, at Nauvoo the Saints envision “people from every land and every nation, the polished European, the degraded Hottentot, and the Shivering Laplander” flowing into that city. [“Report from the Presidency,” Times and Seasons, October 1840.] The saints of Nauvoo anticipated “persons of all languages, and of every tongue, and of every color who shall with us worship the Lord of Hosts in his holy temple, and offer up their orisons in his sanctuary.” [Report from the Presidency,” Times and Seasons, October 1840.]

We can even include Brigham Young in terms of our notion of an openly racial vision. This is from Brigham Young in March of 1847. I know that Brigham Young gets the bad rap for the beginning of the racial ban and I’m not suggesting otherwise. But, it’s not simply that Brigham Young is an inherent racist. We must also understand that in March of 1847 he’s on record with a very open racial vision for Mormonism. So we have a shift in his own thinking about race and Mormonism. This is a meeting at Winter Quarters with a black Mormon, William McCarey. In response to McCarey’s complaints about the way he’s being treated amongst the Mormons, Brigham Young says, “It is nothing to do with the blood, for of one blood has God made all flesh.” He’s paraphrasing Acts. This was typical for religious thinkers in the 19th century to quote Acts in response to the polygenesis theory that permeated the scientific community in the 19th century – that different races must have different genesis or origins. Religious people thought this violated the Bible in “one creation,” and so would frequently quote this verse in Acts, and Joseph Smith and Brigham Young both quote this. “It is nothing to do with the blood for of one blood has God made all flesh.” Then he substantiates his claim of an open racial vision in terms of Mormons’ acceptance of blacks by citing, favorably, Q. Walker Lewis, a black priesthood holder in the Lowell, Massachusetts Branch. Brigham Young, in other words, is on record in March of 1847 favorably aware of Q. Walker Lewis’ priesthood. “We [h]av[e] one of the best Elders[,] an African, in Lowell — a barber,” speaking of Q. Walker Lewis. In the Lowell Massachusetts Branch, Q. Walker Lewis has been ordained an Elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood. He further goes on to tell William McCarey, “We don’t care about the color.” Color doesn’t matter to us. When McCarey complains that because he is black that he is not being treated well, and Brigham Young says, “We don’t care about the color.” So, in other words, even Brigham Young is on record in 1847 as inclusive in his vision.

OUTSIDERS PERCEIVED THAT MORMONS WERE TOO INCLUSIVE IN THEIR CREATION OF THEIR RELIGIOUS KINGDOM

Now change the perspective from the inside to that of the outside. How did outsiders perceive Mormons in terms of their racial vision? For outsiders, they perceived that Mormons were too inclusive in the creation of their religious kingdom. These are just editorials and newspaper reports and books from the same time period. For outsiders looking in at Mormons – and I’ve pulled some quotes from the books and they are all footnoted in the book — the complaint was that Mormons accepted “all nations and colors.” Mormon elders maintained “communion with the Indians,” and walked out with “colored women,” was one accusation against Mormon missionaries preaching in the South. Mormons welcomed “all classes and characters” into their society. They included “aliens by birth” and people from “different parts of the world” as members of God’s earthly family. –These are not compliments. Mormons honored “the natural equality of mankind, without excepting the native Indians or the African race,” was one report from the 1830s. The Mormons “opened an asylum for rogues and vagabonds and free blacks,” was another accusation leveled against them in Missouri. Mormons promoted black “ascendency over the whites,” was another claim from the Missouri period.

I particularly liked this one: Edward Strutt Abdy was a British official on tour of the United States in the 1830s, touring the American penal system. He became enamored with much more than America’s prisons and went back to Britain and wrote a three-volume book about his tour to America, much as Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America.” In this three-volume book, (he called it Journal of a Residence and Tour of the United States) he says, –I got this new book of scripture that was being passed around the United States called the Book of Mormon, and I read it and, wow, this has a very open racial attitude embedded within it that I think will get the Mormons into trouble. He said the Book of Mormon ideal that “all people are alike unto God,” including “black and white,” made it unlikely that the Saints would “remain unmolested in the State of Missouri.” [Edward Strutt Abdy, Journal of a Residence and Tour in the United States of North America, From April, 1833 to October, 1834. 3 vols. (London: John Murray, 1835) 1: 324-325, 3: 40-42, 54-59.] And he proved very prophetic on that count. Outsiders perceive that Mormons are too open and too accepting of people that 19th-century America suggested should be marginalized and segregated. But, in fact, Mormons are welcoming them into their fold.

The charges continue across the course of the 19th century through political cartoons. In 1872 when Brigham Young is brought up on charges of lascivious conduct and hauled off to court, Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun, a New York City magazine, imagines what the scene must have looked like when he is hauled off to court. They simply called this political cartoon, “Affecting parting of Brigham Young from his interesting little family.” What is so striking about the “interesting little family” that it’s an interracial family. The first wife reaching out to Brigham Young is a stereotypical black mammy from the plantation South. Now Southerners promoted this notion of “the happy black mammy” because it is one way of shifting away from the accusation there was interracial sex bound up in slavery, and that their slaves were so fat, well-fed, and happy, and contented that there were no complaints. — But so fat and ugly that no self-respecting Southerner would have sex with them. So that’s the image of the “black mammy.” Now that image, then, is put into Brigham Young’s family. And Brigham Young is doing something that no self-respecting Southerner would do, that is, have sex with a black mammy, but also marry the black mammy. So you have a black mammy in Brigham Young’s family. You also have another black wife, a couple of black children. And then, even if you look at this other wife – if any of you are familiar with the ways in which Irish immigrants are racialized in the 19th century – the suggestion was that they were more ape-like or simian than they were white. That same kind of accusation is then being projected onto the Mormons in this political cartoon. If you look at the facial angle of several of the children and this particular wife, the suggestion is that polygamy is giving rise to a degraded race, and you have Brigham Young’s interracial family here as “evidence” of this.

The New York World published an editorial in 1865. Remember this is the end of the Civil War. Four million blacks have been freed in the South. And the New York World is fearful, then, that because, it argues, black people are racially prone to superstition and racially highly sexed, they make the prime candidates for mass conversion to Mormonism. And they will convert en masse to Mormonism and then American democracy will be at stake because you’ll have Mormons in the Intermountain West combining with these newly freed blacks who have converted to Mormonism and they will control presidential politics in the United States. And it’s a straight-faced editorial published in the New York World. This is just a small segment of that editorial: “The ungovernable propensity of the negroes to miscellaneous sexual indulgence, and a powerful instinct of their race toward unreasoning superstition, will make the four millions of freedmen the most promising field in the world for the propagation of the Mormon faith.” [“Negro Suffrage and Polygamy,” 12 October 1865]

Other political cartoons – this is John Sherwood, “The Comic History of the United States,” published in 1870. You have the enfeebled patriarch out front and then his endless stream of wives and then the endless string of children. Once again, it’s not the number of wives and children that’s so striking, but it’s the interracial nature of the family. Here you have another stereotypical black mammy from the plantation South, you have an Asian wife, and you have either a Native American or a Pacific Islander wife. Once again, polygamy is not just destroying the traditional family; it’s destroying the white race.

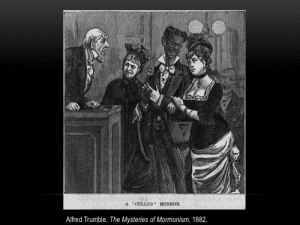

Most of the political cartoons that I found for the book have the white male and then the interracial females. This one is different simply because it’s simply titled “Colored Mormons” published in Alfred Trumble’s The Mysteries of Mormonism in 1882. What’s different is that the Mormon in this situation is a black man. Remember, this is after reconstruction has taken place in the South, and after the troops have been removed from the South by the Federal Government. White supremacists reassert white control of the American South, and you have thousands, and literally thousands, of black men who are lynched, and you can be lynched for looking at a white woman. The “black-beast-rapist” is the myth that Southern whites invent in this period – that black men just want to get ahold of white women. They are projecting that fear on to the Mormons in this situation. The colored Mormon is the black man here who obviously has lecherous intents for the white woman in this political cartoon.

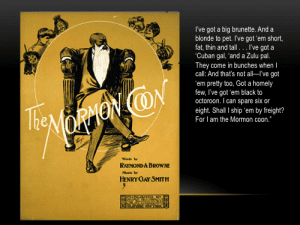

Then as late as 1905 you have Saul Bloom’s publishing house in New York City publishing the “Mormon Coon.” It’s performed on Broadway. Coon songs were a type of music genre popular during the time period, and this one combines negative stereotypes about African Americans with negative stereotypes about Mormons. The chorus of “The Mormon Coon” simply says: “I’ve got a big brunette. And a blonde to pet. I’ve got ‘em short, fat, thin and tall… I’ve got a ‘Cuban gal’ and a Zulu pal. They come in bunches when I call: And that’s not all — I’ve got ‘em pretty too, Got a homely few, got ‘em black to octoroon. I can spare six or eight. Shall I ship ‘em by freight? For I am the Mormon coon.”

So once again, Mormonism and polygamy facilitating race mixing. If you understand how much Americans fear race mixing in the 19th century — the vast majority of states have laws on the books against inter-racial marriage. The Supreme Court doesn’t strike these down until 1967. They’re projecting those fears onto Mormonism. What’s at stake, once again, is democracy. Democracy is the government of a white race. The suggestion is that Mormons are guilty by association or, in other words, facilitating race mixing and making America unfit for the blessings of democracy. The Supreme Court will actually make this point in the Reynolds decision in 1879.

MORMONS MOVE TOWARD WHITENESS

In response, I argue in the book, that you have this struggle over whiteness, and Mormons move toward whiteness. One way they do so in the 19th century is in distance from blackness. Mormons move across the course of the 19th century farther and farther away from their own black converts.

The first documented black Mormon is Black Pete in 1830, the founding year of Mormonism, in Kirtland, Ohio. Within a couple of months, a newspaper in Philadelphia and New York publish that the Mormons have a black man worshipping with them. It’s not a compliment. You have, then, the deterioration from this open racial attitude that I talked about, of the first couple of decades, beginning by the end of 1847.

William Appleby is a convert to Mormonism of seven years in 1847 when he is appointed by the brethren to give a survey of the East coast branches of the Church in the United States. This is the same time that Brigham Young is moving to the Great Basin. William Appleby is, by his own account, traveling over 2,000 miles along the East coast surveying the different branches. He comes to the Lowell, Massachusetts branch, the same branch Brigham Young referred to in March of 1847, favorably citing Q. Walker Lewis as a black priesthood holder in that branch. William Appleby goes there and writes a letter to Brigham Young. William Appleby grows up in New Jersey and certainly has racist attitudes that he brings with him into his Mormonism. You have abolitionists, anti-abolitionists, freed blacks and enslaved blacks all who join Mormonism. Once again, Mormonism is casting a wide net. They are all being welcomed in, but now we’re going to start to order them according to prevailing racial attitudes. And William Appleby is influential in drawing Brigham Young’s attention to the black saints that he meets in the Lowell, Massachusetts branch. So he writes a letter to Brigham Young: “Now dear Br [brother], I wish to know if this the order of God or tolerated in this Church.” This is 1847. If there’s a racial policy in place – I don’t know about it, William Appleby says, and he’s been a member for seven years! But he’s now met Q. Walker Lewis, a black Elder — Is this OK in this church that I’ve joined, “i.e. to ordain Negroes to the Priesthood, and allow amalgamation,” which is the pre-Civil War term for race mixing. Miscegenation is invented during the Civil War as a term to brand Abraham Lincoln as someone who favors race mixing. If you want to free the slaves, the anti-abolitionists say, what you really want is to mix the races. They refer to the Emancipation Proclamation as the Miscegenation Proclamation. They invent that word. But before the Civil War the term in usage is “amalgamation,” the mixing of the races. Do we allow this in this Church? William Appleby writes to Brigham Young in June of 1847. He’s not only met Q. Walker Lewis, an ordained, black Elder, but he’s met Enoch Lewis, Q. Walker Lewis’ son, who is black, who has married Mary Webster, who is white. And they are both members of the branch in Massachusetts. My goodness, do we allow this in this church? He says in his letter to Brigham Young. [“…If it is I desire to know it, as I have yet got to learn it.” William I. Appleby, Batavia, New York, to Brigham Young, SLC, Utah, 2 June 1847.]

Brigham Young, remember, goes to the Great Basin, and then returns to Winter Quarters and meets with William Appleby on the third of December 1847 at Winter Quarters. Now some who have read the minutes of this meeting suggest this is the beginning of the priesthood ban. From the minutes of the meeting, the meeting lasts for about four hours. We get thirteen lines and they don’t say anything about priesthood. And so I am hesitant to suggest that the priesthood ban begins here because the minutes don’t say so. They don’t say anything about priesthood, but they do talk about race mixing and Brigham Young comes out very strongly against mixing of the races. “Capital punishment should be the penalty,” he says. And he will repeat that on other occasions.

On the 23 of January 1852 to the Territorial Legislature, Brigham Young will give the first open articulation of a race-based priesthood restriction by a Mormon prophet-president. It’s to the Territorial Legislature as they are attempting to write a servant-code, or a slave-code, to define the laws that will govern the black slaves who have been brought to the Great Basin by their slave masters who have converted to Mormonism. Some of those slaves are Mormons themselves. Once again, this open racial vision –we’re accepting all people: abolitionists, anti-abolitionists, blacks, freed blacks, enslaved blacks, slave-masters — they are all gathering to the Great Basin. Now we need to figure out how to order them. And Brigham Young will suggest in 1852 that white should take precedent over black.

On the 5th of February 1852 he will give his most forceful articulation. In chapter 5 of the book, I do a thorough deconstruction of this speech. I won’t go into in here, but nonetheless it’s really the most open and forceful articulation of a racial priesthood restriction. “They will not rule over me in this church and they will not rule over me in this territory.” It is in response to an election code that the Territorial Legislature is debating. Most historians who have looked at this in the past have suggested it comes out of the servant code. They argue that this fifth of February speech actually comes in a debate with Orson Pratt over the election code. We know that Orson Pratt gives a speech, because it’s been covered in the minutes of George Watt, who was the scribe for the Territorial Legislature, and it had never been transcribed. The Church History department asked LaJean Carruth to transcribe it after we identified this speech from the 1852 legislature and used it in the book for the first time. We know that Orson Pratt doesn’t like the stance that Brigham Young is staking out and gives a speech on the 27th of January 1852 against the servant code. He argues or moves that the Legislature should “reject” it in its entirety. He argued that only God administered divine curses and that they were particular to a given time and place. They didn’t automatically pass down from generation to generation. He says that curses are not multi-generational. He says, “Shall we take then the innocent African that has committed no sin and damn him to slavery and bondage without receiving any authority from heaven to do [so]?” He argues that Mormons are not acting on authority from God if they pass this servant code that they are debating. He found the idea “preposterous” and he said that is was “enough to cause the angels in heaven to blush.” We know that Brigham Young and Orson Pratt had butted heads before, and this is just another example of Brigham Young and Orson Pratt butting heads again.

The minutes of the Legislative session give us an indication that Orson Pratt speaks on the 4th of February. Unfortunately that speech was not recorded by George Watt. I don’t know what he said on the 4th of February. But Brigham Young, then, gives his most forceful articulation of a priesthood restriction on the 5th of February. I think it’s in debate with Orson Pratt. Following that speech you have Orson Pratt, I think, pushing back again. One way he does so, there are two seemingly innocuous bills that come up for consideration, after Brigham Young gives his speech, and Orson Pratt votes against both of them. He votes down the Cedar City municipal bill and the Fillmore incorporation bill. Hey, who cares if Cedar City and Fillmore are incorporated?

Well, the minutes of the legislative session tell us why Pratt does so – because the provisions in those bills suggest or stipulate that only white men over age twenty-one are allowed to vote in Cedar City and Fillmore. It’s the same language that had passed the day before for the election law for the entire territory of Utah, white men over 21. This is standard fare for 1852 America, nothing remarkable.

Orson Pratt actually argues that black men should be allowed to vote, and he votes against the Cedar City and Fillmore bills because they don’t allow black men to vote. “Councilor Pratt opposed the bill on the ground that colored people were there prohibited from voting,” the legislative minutes tell us. [Legislative minutes on Fillmore incorporation bill.] So he’s staking out a very progressive attitude towards black rights at the same time that Brigham Young is arguing for a racial priesthood restriction – that black people will not rule over us in Utah Territory and they will not rule over us in the Mormon church.

What does this mean for the black priesthood holders? Elijah Abel will see, then, this transition across the course of his lifetime in terms of open participation for blacks. He’s ordained an Elder on the 3rd of March 1836. This is sanctioned by Joseph Smith Jr. He’s ordained a member of the third quorum of the Seventy on the 20th of December 1836 by Zebedee Coltrin. In 1879 he applies to John Taylor to receive his endowments. He’s received his washing and anointing in the Kirtland Temple. He’s baptized for the dead in Nauvoo. He moves to Cincinnati before the endowment ceremony is introduced. I don’t know what would have happened had he been there. I did quote to you the attitude articulated in Times and Seasons, the Mormon newspaper, about who is welcomed into the Nauvoo Temple and remember it said “all colors.” But he had moved to Cincinnati by that point. There is a belated remembrance that he applies to Brigham Young for his endowment. I find no written contemporary evidence of that. What does survive in the historical record is his 1879 appeal for his endowment and to be sealed to his wife. There is an investigation conducted by John Taylor who is leading the Church as the head of the Quorum of the Twelve at the time. If the racial priesthood restriction is unambiguously in place as late as 1879, why do you need to have an investigation?

The leader of Mormonism isn’t sure what to do. If it’s unambiguously in place, why do you need an investigation? The investigation takes place. They conclude that Elijah Abel’s priesthood will be allowed to stand, but they won’t allow him temple admission. And so the lone surviving black priesthood holder is used to begin to formulate a temple restriction which will then impact not just black men, but black women as well. Elijah Abel goes on a third mission for Mormonism even after he has been rejected admission into the temple. He returns from his third mission and within a couple of weeks he passes away. His obituary is printed in the Deseret News. I don’t know who writes his obituary, but it’s not a typical eulogy. It is more a confirmation of his status as a black priesthood holder than it is a typical eulogy. It goes through the certificate dates for his priesthood ordinations. Whoever writes this is very much aware of the shrinking space for black Mormons at the time and is pushing back as much as possible saying – hey, here are his priesthood certification and ordination dates, and he was a faithful Latter-day Saint up to the end.

By 1907 you have the firming up of this policy: “The descendants of Ham may receive baptism and confirmation, but no one known to have in his veins negro blood, (it matters not how remote a degree)” — so we are applying the one-drop rule by 1907 — “can either have the Priesthood in any degree or the blessings of the Temple of God; no matter how otherwise worthy he may be.” This is a first presidency statement from 1907. [Extract from George F. Richards Record of Decisions by the Council of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, (no date given but the next decision in order is dated 8 February 1907) in George A. Smith Family Papers, ms 36, box 78, folder 7, Manuscripts Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.]

RESTRICTION IS SOLIDIFIED, 1908

I basically argue in the book that the restriction is solidified in 1908 by Joseph F. Smith. For the priesthood restriction to be solidly in place, what I believe you have to have is you have to be able to erase from collective Mormon memory the black priesthood holders. You have to then put in place a white priesthood in white temples and that becomes the new memory moving forward. We can trace this transition over time with Joseph F. Smith himself. So in that 1879 investigation, he actually interviews Elijah Abel for John Taylor in that meeting that takes place in 1879. He comes back to that meeting and he says, “Abel showed me his priesthood certificates.” He defends Abel’s priesthood. Remember, the decision was Abel’s priesthood was allowed to stand in 1879. He defends it as valid again in 1895 in another meeting of the Brethren; he reminded LDS leaders that Abel was ordained to the priesthood “at Kirtland under the direction of the prophet Joseph Smith.”

Then you have the beginning of the slippage. In 1904 he called Abel’s ordination a mistake that “was never corrected.” And then, in response to a letter from the mission president of South Africa who says, “We just baptized Zulu chief and he wants to take the gospel to all of his tribe. What do we do about this?” The Brethren meet, and Joseph F. Smith in 1908 says that Abel’s priesthood “ordination was declared null and void by the Prophet himself,” meaning Joseph Smith. So you see the transition over time in the way that he’s remembering Elijah Abel. Abel has been dead for now thirty years. You have then a replacement of a mixed and open attitude toward temple and priesthood with a white attitude toward temple and priesthood. They also decide in that same meeting that missionaries, “should not take the initiative in proselyting among the negro people, but if Negros or people tainted with negro blood apply for baptism themselves, they might be admitted to Church membership in the understanding that nothing further can be done for them.”

Take that statement and compare it with the open attitude that I described for the first twenty years of Mormonism. You see, then, the space for full black participation shrinking over the course of the 19th century. Mormonism is passing as “white.” One way in which you claim whiteness for yourselves is in distance from blackness. By 1908 they have put segregated priesthood in temples in place.

21st CENTURY MORMONISM

So successful are Mormons at claiming whiteness for themselves that by the 21st century when Mitt Romney runs for the presidency it becomes popular fodder. In 2008 a political blogger made fun of the Romney Christmas card. It’s the very white and polished Romney family, and he photoshops an African American man into the Romney family photo and then makes fun that the “Romney Xmas Card represents the melting pot that is Utah.” “Who do you think is the non-Romney (or Nomney) in this photo?” [www.236.com]

Then in 2012 Lee Siegel publishes an editorial in the New York Times calling Mitt Romney “the whitest white man to run for president in recent memory.” [Lee Seigel, “What’s Race Got to Do With It?,” The New York Times, January 13, 1012.]

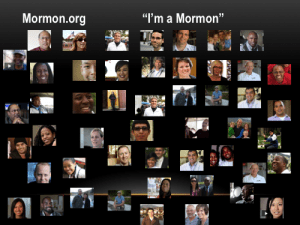

The argument that I make in the book, the over-all trajectory, is simply that in the 19thcentury, Mormons are denigrated as not white enough and attempted to claim whiteness for themselves. By the 21st century, Mormons are denigrated as too white and try to claim a more racially diverse and internationally identity for themselves. In the 21st century, witness the “I’m A Mormon” campaign. Before she decided to run for U.S. Congress – she was featured in the “I’m A Mormon campaign” – Mia Love with her white husband and interracial children. A pretty dramatic transformation from the 19th century to the 21st century. Not white enough to too white is the basic trajectory that I trace. Thank you.

Q&A

Q. I always wondered if Brigham Young’s reversal of his thoughts and feelings regarding blacks was fear of a repeat of the persecution and expulsion of the Saints. Care to comment?

A. By the time we have Brigham Young’s reversal, it’s 1852 and the Saints are in Utah Territory. I’m not sure that he’s as much fearful of a repeat of the persecution as much as he is trying to deal with those who have been gathered to the Great Basin. So the very open attitude the first couple of decades of Mormonism, then, by 1852 in Brigham Young’s mind, creates a need to order the people who have been gathered. He says white over black and free over bond – so all are like unto God, black and white, bond and free? As the territorial legislature meets, he’s just simply saying, well, white is going to take precedence over black, and free will take precedence over bond. Remember that the Presbyterians, the Methodists, and the Baptists all either experience schisms or splits in the 19th century. Mormonism avoids that. It doesn’t have a split over these racial issues, because it simply says we accept everyone. Slaves and slave masters, you’re all welcome. But by 1852 they attempt how to figure out how to order that group of people who have gathered to the Great Basin – abolitionists and anti-abolitionists. I think he’s mostly responding out of that immediate context. And the speech is drenched in racism, I mean, it’s horrible. He speaks out really dramatically against black-white race mixing. And like I said, I give you the full deconstruction of that speech. We went back to the Pitman shorthand version. Most people who quote Brigham Young’s speech from 1852 quote Wilford Woodruff’s truncated version. Woodruff is in the legislature and he writes down an 800-word summary of a 2300-word speech. George Watt is recording in Pitman shorthand. We went back to the Pitman shorthand version. I think Woodruff got a few things wrong. I hope historians stop quoting Woodruff’s version and will now only quote the shorthand version.

Q. Did you write the Gospel Topics essay on race and the priesthood? If so, how were you chosen? What major changes were edited out of your writing?

A. You’re calling me out in front of everybody. I have people in the room who are from the Joseph Smith Papers project who are going to report what I say here, no doubt. Yes, I did help with the Gospel Topics essay. What appears online was what the Church History Department produced from a 55-page essay that I wrote that was approved by the Brethren. Then the Church History Department reduced that down to what was put online. How were you chosen? Have you seen Toy Story – that claw in…? [laughter and applause] I don’t know if the presumption is that I wasn’t qualified, with this question or not. My friends at the Church History Department were aware that I was doing research on this book. That was the desire, as I understood it, for the Gospel Topics essay, was to tap some scholars who were already doing research in whatever topic area that was being addressed. They were aware that I was doing research for this book. They asked if I was willing to help. What major changes were edited out of your writing? I’m not going to address that.

Q. We have from latter-day apostles – promoting segregation, Martin Luther King as a Communist, they sound racist. Were the apostles acting in protection of the Church or were they simply racist?

A. Everyone has to sort of figure that out for themselves. I certainly see and I hope that in the book I place at least Brigham Young and the other leaders’ attitudes within the context of their time periods. But, what I think and what everyone else thinks – it’s sort of a personal assessment.

Q. Appleby’s letter to Brigham Young, 2nd of June 1847, Pioneer Day, July 24th 1847. I don’t believe there was a Salt Lake City before the Saints even arrive?

A. Someone is challenging the way that I put that on the slide – yeah you’re right. He was sending it to Brigham Young wherever he was. I don’t have evidence the Brigham Young received it until he got back to Winter Quarters. So I will correct that on the slide – thank you.

Q. Is it reasonable to say the priesthood ban actually preserved the young church during difficult racial times?

A. I’ve heard that argument before. If you are going to argue that the priesthood ban preserves the Church, then why polygamy? They certainly came under scorn for polygamy. The priesthood ban sort of made them like the rest of white America. Polygamy brought all kinds of scorn upon them.

Q. Can you explain how this racial perspective may tie into Mormon views and practices of eugenics and social Darwinism?

A. Some of the speeches that come from the inside sound as if they are anticipating the eugenics movement. I simply argue in the book that you can’t take the speeches from the inside, especially the 1870s and 1880s, without understanding the way that the Mormon body was being denigrated from the outside. So yeah, it’s certainly sounds like Mormonism is anticipating the eugenics movement – an angelic, celestial, elevated race coming out of the Great Basin. But it’s in response or in dialogue with the denigration from the outsiders. So it does anticipate some of the eugenics arguments being made by the turn of the 20th century.

Q. You should write a book on the Mormons move toward whiteness.

A. I think I did.

Q. Is Joseph F. Smith’s 1908 declaration that Joseph Smith declared Elijah Abel’s priesthood null and void the result of Zebedee Coltrin’s report to John Taylor on Joseph’s regret after ordaining Elijah Abel?

A. I don’t think that – there’s no evidence that Joseph F. Smith is remembering back to Zebedee Coltrin. Coltrin does report in that investigation in 1879 that Abel’s priesthood was rejected by Joseph Smith, but no one buys it in 1879 because Joseph F. Smith actually goes to Elijah Abel, and comes back to the meeting and says – look, these are the ways in which Zebedee Coltrin’s memory is flawed. Zebedee Coltrin says that he gave Elijah Abel his washing and anointing. And Elijah Abel says – no he didn’t. I do have evidence that Zebedee Coltrin ordained Abel as a member of the third quorum of the Seventy. He says in that 1879 meeting – when I placed my hands on the black man’s head, I felt so uncomfortable, I said I would never do so again even if the Prophet commanded me to do so. He says that’s when he gave Elijah Abel his washing and anointing. Elijah Abel says – no, he didn’t give me my washing and anointing. He ordained me a member of the third quorum of the Seventy. I’ve been able to verify that he ordained Elijah Abel a member of the third quorum of the Seventy and I trust Elijah Abel’s memory. He doesn’t say who gave him his washing and anointing, he just says in wasn’t Zebedee Coltrin. Zebedee Coltrin’s memory is flawed in other ways in other words – I don’t think that’s impacting Joseph F. Smith in 1908.

Q. How do you explain the Book of Mormon statements of the skin color curse and its purpose to prevent intermarriage?

A. The Book of Mormon was never used by any leaders of Mormonism to justify priesthood or temple restriction against African Americans. They only understood the Book of Mormon to impact their vision of who Native Americans are and whatever they understood, certainly they understood those verses literally. They argued and believed that it was simply cultural and could be overcome – that Mormonism was a part of the redemption of these fallen descendants of ancient Israel. The 19th century Mormon goal was to bring them towards whiteness along with white Mormons. Brigham Young tells Mormon missionaries to marry Native American wives and help make them “white and delightsome.” He never applies those verses towards African Americans. Brigham Young’s only justification for the racial priesthood restriction was the curse of Cain – Cain killing Abel. He never resorts any other justification. He goes to the Bible, never to the Book of Mormon for his justification. Those verses were only applicable to Native Americans in the 19th-century Mormon mind.

Q. Mormons were often compared to Muslims. Do you deal with this in your book?

A. Yes. There’s a chapter, “Oriental, White and Mormon,” where I deal with comparisons to Islam as well as to Turks and Chinese. Mormonism is an oriental problem on America soil. The same congress that passes the Chinese Exclusion Act also passes the Edmunds Act. The arguments in the newspapers of the time were solving both oriental problems at the same time.

Q. At one point, Brigham Young, I thought, accepted interracial marriage when confronted by William McCarey. Is this true? And if so, what is your opinion about why this changed?

A. He doesn’t really talk in the meeting with William McCarey about interracial marriage per se, but William McCarey’s white wife is present in the meeting. But the conversation doesn’t go towards race mixing and interracial marriage in that 1847 meeting.

Q. How did the Church leaders explain to the Church population a reason for denying blacks the blessings of the temple? Did they ever say why? Did they explain their own change of opinion?

A. The blessings of the temple – the resort is to the Curse of Cain. It just is a spillover from the priesthood restriction. The day that Elijah Abel dies, Jane Manning James begins her appeal for her temple endowment, and she writes letters to a variety of Church leaders and the response is always Curse of Cain. You are of cursed lineage and therefore you are barred from the temple.

Q. If there was no revelation prohibiting blacks from obtaining the priesthood, why was a revelation needed to rescind the prohibition?

A. The way I see it is simply because LDS leaders became so convinced that it was in place from the beginning, that God put it in place, and that we can do nothing about it. It will take a revelation to get rid of it. In 1908, I argue, this is the last brick in this racial priesthood restriction. It’s firmly in place in 1908. You have to erase from collective Mormon memory the black priesthood holders and make it into a white memory. It’s clean and it’s tidy and it’s there from the beginning. Elijah Abel is dead. Jane Manning James is dead in 1908. The black prominent pioneers who are agitating for inclusion are now gone, and we can construct a white vision of our past, uncomplicated. In the last chapter of the book I just trace their transition from Brigham Young to lay it at the feet of Joseph Smith, and from Joseph Smith to God. We can’t do anything about it. It will take a revelation to get rid of it. And in fact, it takes a revelation in 1978 to get rid of it.

Thank you.