Good afternoon. Today we are going to discuss two things related to the issue of style in the Book of Mormon. First, we are going to discuss the style of Book of Mormon writer or writers, and second we will talk about scriptural style in the Book of Mormon.

Latter-day Saints believe the Book of Mormon is exactly what it purports to be, a record containing the writings of multiple ancient prophetic authors. Few critics of the Book of Mormon have paid much attention to the distinction between writers set forth in the text. But, even for those who reject Joseph Smith’s account of the Book of Mormon, the issue of single or multiple authorship has long been a question of some disagreement.

In 1831 Alexander Campbell claimed “the book professes to be written at intervals and by different persons during the long period of 1020 years and yet for uniformity of style there never was a book more evidently written by one set of fingers nor more certainly conceived in one cranium than this same book. If I could swear to any man’s voice, face, or person, … assuming different names, I could swear that this book was written by one man, and as Joseph Smith is a very ignorant man, I cannot doubt for a single moment but that he is the sole author and proprietor of it.”

In Mormonism Unveiled, that granddaddy of all anti-Mormon books, E. D. Howe seemed confident that “no one can be left in doubt in identifying the whole Book of Mormon with one individual author”, and again, “it was framed and written by the same individual hand”, but when he goes on to claim that it “was also the joint production of Solomon Spalding and some other designing knave”, namely, Sidney Rigdon, one senses some degree of confusion and perplexity on the matter.

Subsequent advocates of variations of the Spalding/Rigdon theory have sometimes suggested the contributions of other associates of Joseph Smith, such as Parley P. Pratt, Oliver Cowdery, or someone else. But most contemporary critics tend to favor a single author theory to explain Book of Mormon origins.

Coming from a different perspective, as a Latter-Day-Saint scholar, John Tanner has noted that Jacob, the brother of Nephi, appears to have a particular style all his own which contrasts sharply with that of other writers, but is consistent with the events of his life, as described in the text of the Book of Mormon.

Tanner observes:

[Jacob has] a vivid, intimate vocabulary, either unique to him, or disproportionately present. Two thirds of the uses of the word “grieve” and “tender’ (or their derivatives) are attributable to Jacob. Likewise, he is the only Book of Mormon author to use “delicate,” “contempt,” “lonesome,” “sobbings,” “dread,” and “daggers.” He deploys the last term in a metaphor about spiritual anguish: “daggers placed to pierce their souls and wound their delicate minds” (Jacob 2:9)…

Similarly, Jacob alone uses “wound” in reference to emotions and never uses it (as do many other authors) to describe the physical injury of a person. Jacob uses “pierce” or its variants four of nine instances in the Book of Mormon, and he alone uses it in the spiritual sense.

Such stylistic evidence suggests that Jacob lived close to his feelings and was gifted in expressing them.

In another interesting study Roger Keller examined the use of content words by Book of Mormon writers. He found that Mormon’s usage appeared to be distinct from other Book of Mormon writers in several ways. These include Mormon’s use of the word “command” to mean leadership, his use of the word “earth” to refer to the ground, and Mormon’s almost exclusive use of directional language in connection with the land. As Keller notes, he is the geographer, “par excellence.” In contrast to other writers of the Nephite records, Mormon “has almost no emphasis in the theological area.”

Moroni speaks of a land as one of promise and inheritance while his father focuses on the land as a geographic and often localized entity.

Grant Hardy in a book that’s been mentioned already, “Understanding the Book of Mormon”, has observed that Mormon is also a rather non typological. “Mormon never speaks of war figuratively or makes it as a metaphor for Christian living.” “There is no mention of putting on the armor of God,…or spiritual warfare against temptation in contrast to Latter-day Saint readings of the war chapters in Alma.”

“Although Mormon occasionally quotes people who identify certain things or events as ‘types’, typological thinking is not a major actor in his own understanding of history. The only time he refers to types, he is describing the beliefs of others: ‘they did look forward to the coming of Christ, considering that the Law of Moses was a type of his coming.’ (Alma 25:15). By contrast, Moroni does offer an explicitly typological explanation in his own voice in Ether 13:6-7.” These and other elements, according to some readers, seem to set him apart from other writers in the Nephite text.

A separate approach is exemplified in the work of other scholars over the last few decades (you probably didn’t know that these two scholars wrote on the Book of Mormon) who have studied the use of non-contextual words in the Book of Mormon text. These studies indicated a diversity of style in the text, which is consistent with the diversity of writers set forth in the text.

Mostellar and Wallace were not Latter-day Saint scholars, but their research on what we would call word-prints today basically set the stage for Latter-day Saint scholars to apply some of these methodologies to study the Book of Mormon.

Larson and Rancher, of course, had an early study, first published in ’79 and republished in 1982. You have the work of John Hilton in the 1990s, and more recently Paul Fields, Bruce Schaalje, myself, and quite a number of young scholars, have been working on additional material that’s been published.

Instead of jumping ahead, let me just summarize. Each of these groups of scholars has found evidence for a multiplicity of authorship in the Book of Mormon, that is, that there were multiple writers within the Book of Mormon, and interestingly enough, the evidence also suggested in each case that these writers, that are separate writers in the Book of Mormon, at least some of them, are quite distinct from 19th century authors that have been proposed as possible counter explanation authors for the Book of Mormon.

Bob Reese mentioned Earl Wunderli today, who challenges the claim that there were multiple writers in the Book of Mormon text and he devotes an entire chapter in his book to the question. He argues that if the Book of Mormon purports to be written by different writers, differences in the vocabularies of these purported writers should be detectable. He discusses the frequencies of words and phrases for Nephi, Jacob, Mormon, Moroni and the resurrected Jesus in Third Nephi and concludes that there is little if any difference among various writers of the Book of Mormon, and that just one person: Joseph Smith wrote the entire text.

The methods used for data comparison and reasoning present a fertile field of discussion for such an investigation, but Wunderli’s methodologies lack statistical validity. He mostly describes only grammatical uses of words, and provides raw word counts and summaries to make comparisons. Had he used more appropriate methods, he might have been surprised at what he had found.

At this point I am going to turn some time over to Paul to discuss this for a few minutes, and I will be back on another subject.

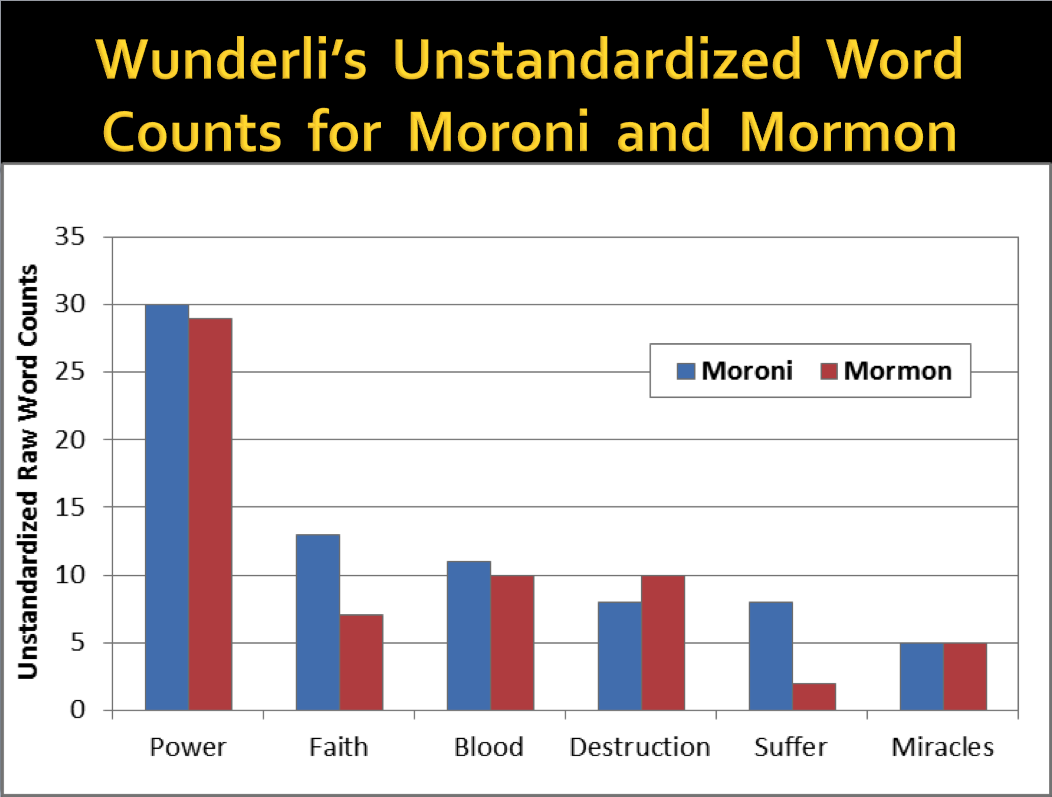

Let’s take a look at some of the analysis, the internal evidence that Wunderli refers to. He picks out six words: “power”, “faith”, “blood”, “destruction”, “suffer”, and “miracles”, as being words that show no difference between the word pattern choices and frequencies of word usages between Moroni and Mormon as speakers within the Book of Mormon.

For example, the word “power” is used about 30 times by Moroni and 29 times by Mormon, meaning not much difference. But the difficulty with his analysis is: this is the same as saying there were 30 cases of a disease in Utah and 29 cases of that same disease in California, therefore the health status of those two states is the same. Well, the population of California is 10 times bigger than the population of Utah, so the comparison is an invalid one. If we standardize the use of words in the Book of Mormon for those six words, we find that with a comparable basis of 100000 words, the frequency of the use of the word “power” by Moroni is much greater than by Mormon. Their word pattern ratios, their word pattern frequencies show distinct differences in preference for those six words.

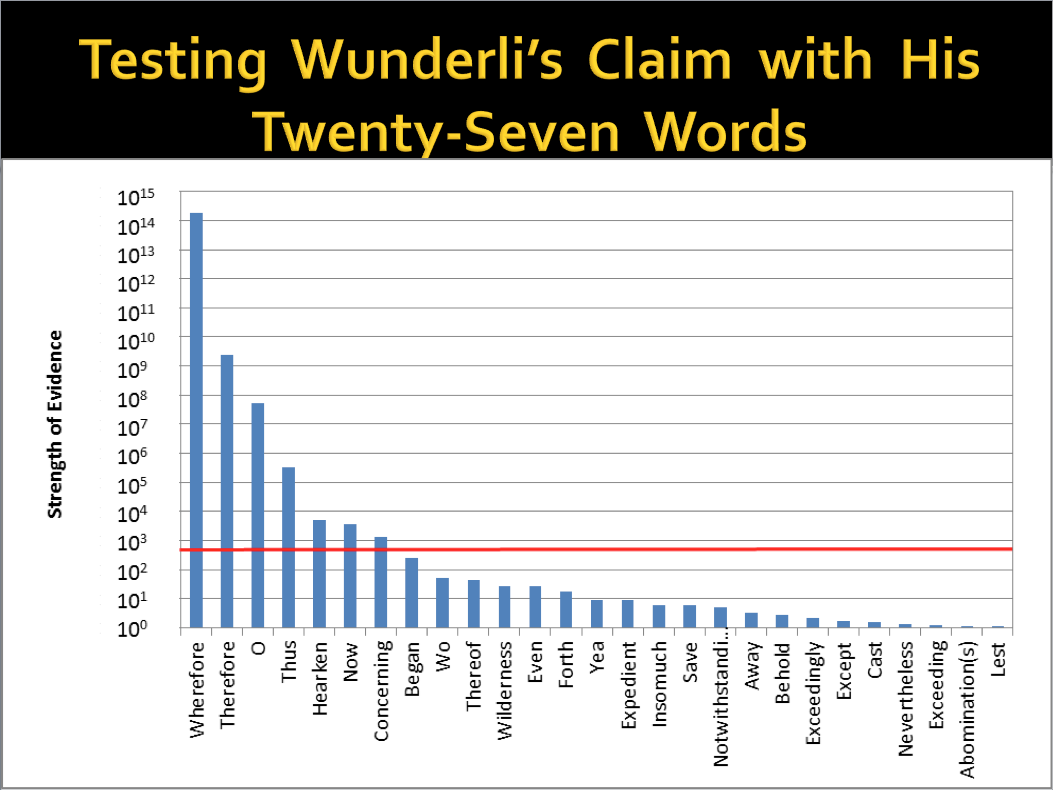

Wunderli also says that there is a broader set of 27 words that show no difference. However, when we use statistical tests on a comparable basis for these word frequencies, we find, for example, that for these seven words, where the blue bars are the highest, there is over a trillion times difference in the frequency of those words amongst the authors as stated. The strength of evidence for a difference between them is overwhelming.

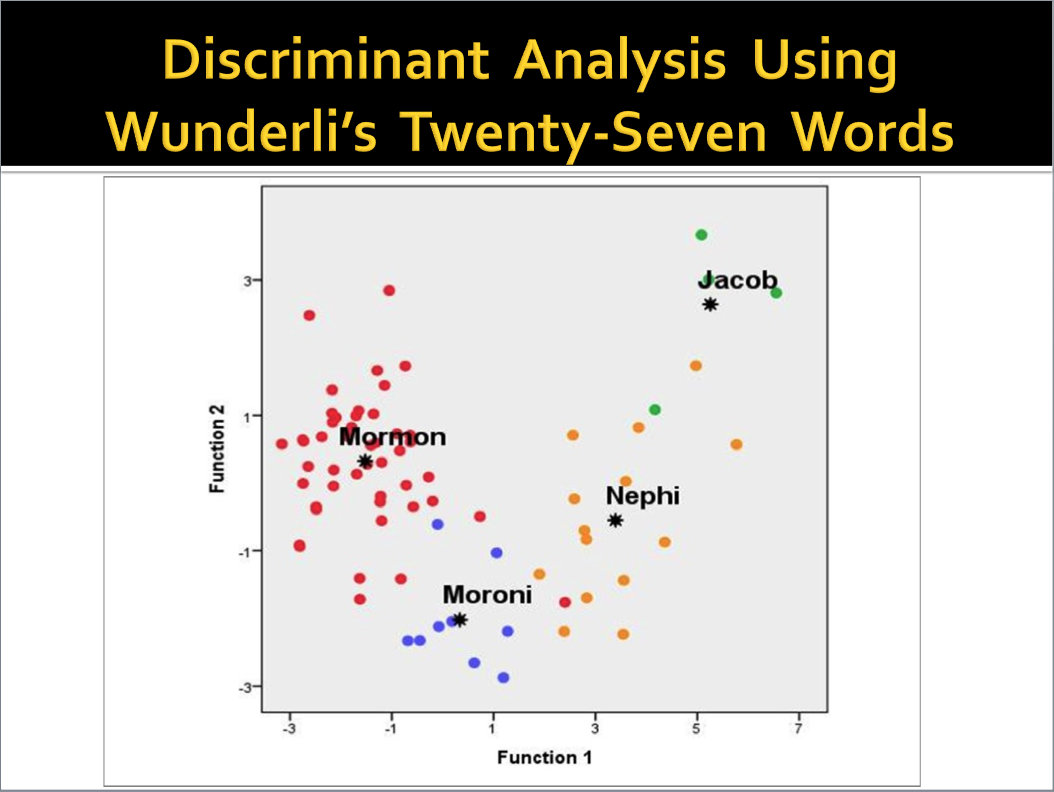

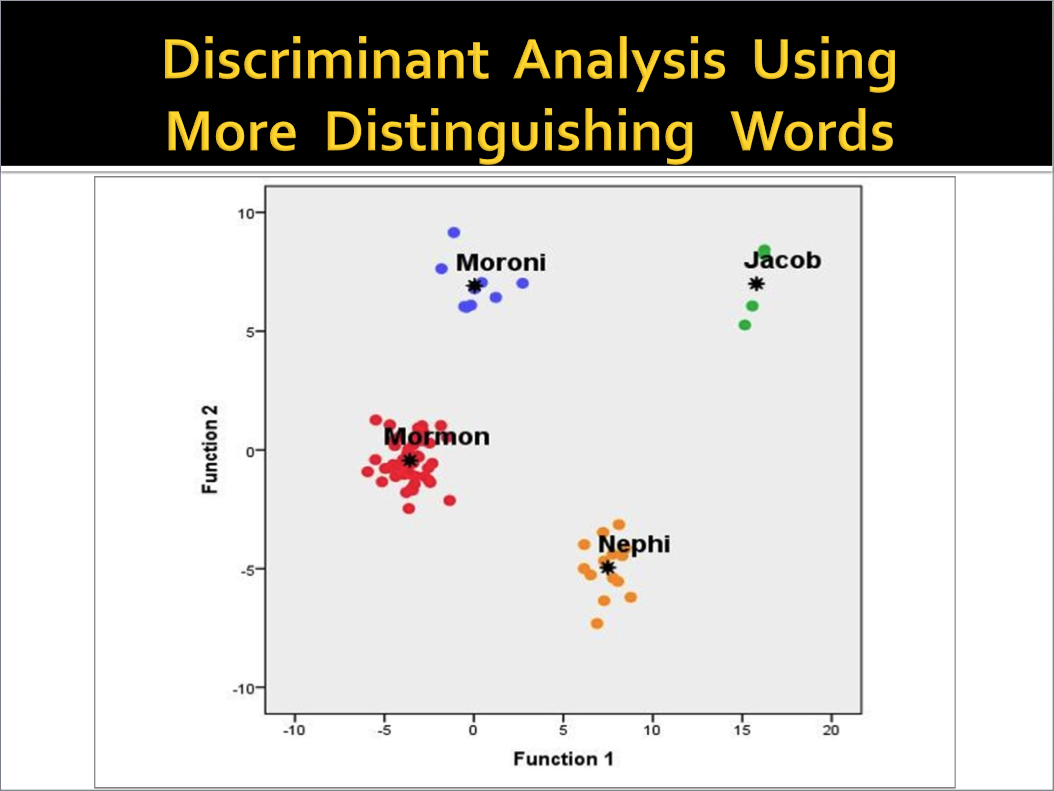

Using discriminate analysis, which in a two dimensional space will separate clusters of items, we find that using his 27 words, Mormon forms one cloud of dots, representing the texts that we can attribute to Mormon. Moroni is the blue dots, Nephi is the orange dots, and then Jacob is off to the far right in the green dots–distinctly different word pattern usages.

If we, however, use a more distinguishing set of words than those 27 that were chosen on a simplistic basis by Wunderli, the distinctions become even more clear.

Wunderli takes a look at the quotations by Jesus, the Christ, in the New Testament and in the Book of Mormon, and he looks at the words that are used there, and he says they are distinctly different from each other. However, again, when using statistical analysis techniques to evaluate that claim, we find that there is only one word that is used differently by the Christ in the Book of Mormon and in the Bible and that is the word “Behold.”

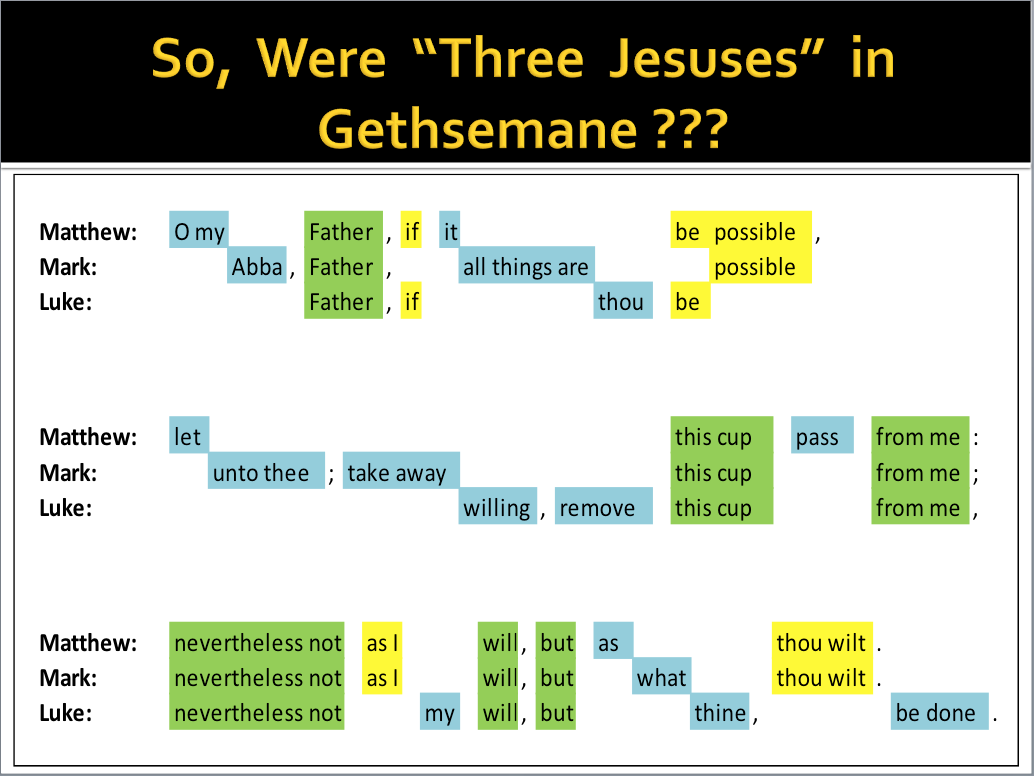

Interestingly if we will take the three renditions of the prayer in Gethsemane by Mathew, Mark, and Luke, and put them in parallel with each other, and look for similarities in the wording, we find in the green there are a few words that are used the same in the same place in all three renditions of the prayer. In blue are where the words are the same twice, and then in yellow where they are different. What we can conclude from this is, even in the New Testament, there must have been three Jesuses, not just one!

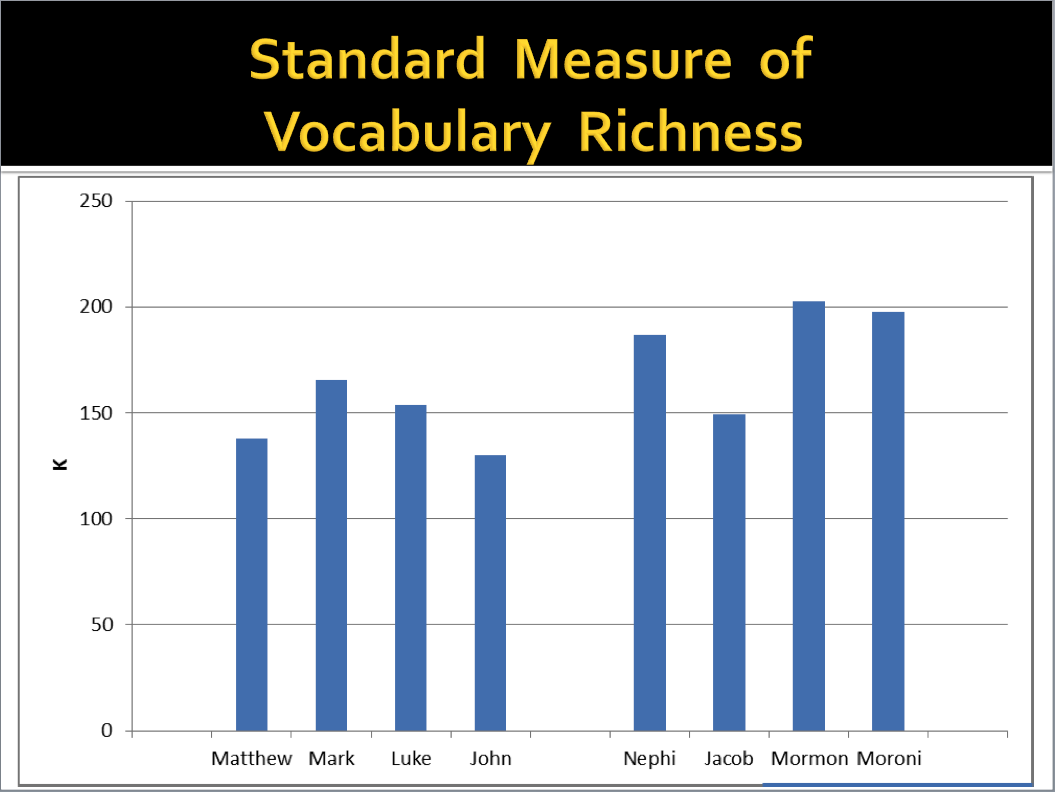

Wunderli talks about vocabulary richness, where vocabulary richness refers to the breadth of a writer’s vocabulary, how many words that writer uses, and claims that there is no difference between them. However, if we use the vocabulary richness statistic that is accepted in the stylametric field, that is referred to as “K”, we apply that to Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John, and we see some comparison differences there, where Mark has a more rich vocabulary than the others. If we look at Nephi, Jacob, Mormon, and Moroni, we see that Mormon and Moroni have very close to the same vocabulary richness. Interestingly those four speakers have a more rich vocabulary in the Book of Mormon than within the Gospels in the New Testament.

Now since the King James Version of the Bible was a translation product of 54 learned men, who spent four years doing their work, and the Book of Mormon was the translation product of one unschooled farm boy, over about a 90 day period of time, we can say then that there is 250 times as much effort per word, that went into the translation of the King James Bible, as compared to the Book of Mormon, and if Joseph Smith alone could have accomplished that feat, he was indeed a remarkable man.

So our conclusion is there is very strong evidence in fact that the major Book of Mormon authors are distinguishable and the writing style in the Book of Mormon is at least on par with that in the King James Version of the Bible, an amazing feat even for a literary genius, but maybe not quite so amazing for a prophet of the Lord.

We are going to talk a little bit now about style, we call the Biblical style. Readers of the Book of Mormon have been aware of the influence of the Bible on the text of the book from the beginning. The nature and significance of that influence, however, has often been a matter of dispute, no one questions the Book of Mormon appeared in a Biblically saturated culture.

[American Zion] is a very interesting book and it’s actually pretty good and a recent one by Eran Shalev. He discusses the influence of the Bible on early American culture, in the pre-Civil War period. There he discusses a genre of writing found in some political and historical texts, called the scriptural style, or the ancient historical style. Shalev himself gives it the name Pseudo-Biblicism.

This style adopted archaic language found in contemporary English Bibles reminiscent of the Biblical Book of Chronicles or Judges, and included the use of words like” thee”, “thy”, “thine”, instead of “you” or “yours”, and verbal endings such as “est”, and “thereof”, were typical

Pseudo-Biblicism was popular from about 1750 to about 1850 after which it seems to have fallen out of use. Notable examples of books written in this style are The First Book of Napoleon, by Eliakim the scribe, a book that appeared in 1809; The American Revolution by Richard Snowden in 1823; and The Late War between the United States and Britain by Gilbert Hunt in 1816.

Examples also appeared in some newspapers. Here is an example from one such article published in The Richmond Enquirer, I think, in 1812. Let me just read to you to give you a flavor for it. “And it came to pass in those days, that there was no King in all the land, even in all Columbia, but everyone walked after the imagination of his own heart. And the people said one to another, ‘We will choose from among our own number Elders to rule over us; even discreet men, out of all the land of Columbia from the borders of the Great Lakes, Northward, till thou comest to the plains of the South, which abounds with oranges, Pomegranates and Figs. And let all the Elders meet together in the great city, even the city of Philadelphia, and make laws for us, for why should our goodly heritage be given up to strangers?’” Ok, there you go; it’s South Carolina, not Virginia.

Shalev agrees that the Bible influenced the Book of Mormon text, but he also argues two things. First, he argues that these particular texts that he refers to influenced the readership of the Book of Mormon that it may have prepared people in a way to read a book like the Book of Mormon that was written in Biblical language.

A second thing he argues is that it may have also influenced the text of the Book of Mormon on Joseph Smith as either translator, or, as some supposed, that Joseph Smith was making up the Book of Mormon, that it influenced his language. For example, he knows “The tradition of writing in biblical style paved the way for the Book of Mormon by conditioning Americans to reading American texts, and texts about America in biblical language.” [Shalev, American Zion, 104]

“The pseudo-biblical tradition seemed to have numbed America’s sensibilities towards the mobilization of sacred language….By acculturating Americans to texts about America written in Biblical language, the pseudo-biblical tradition helped pave the way for the Book of Mormon”, or so he argues [Shalev, American Zion, 116]. “Americans who had been reading texts akin in important aspects to Joseph Smith’s bible for many years before its publication, were thus conditioned to comprehend texts written in biblical style….” [Shalev, American Zion, 116] You get the general idea.

Now, Shalev also argues that this may, in addition to influencing readers, that it actually may have influenced the text of the Book of Mormon. “By including American pseudo-biblicism in the intellectualism inventory of the Second Great Awakening, Scripture and contemporary newspapers might possibly have been content enough to build the literary and imaginative (or religious and divine) framework for an American bible” [Shalev, American Zion, 112].

Recently two critics of The Book of Mormon, a little over a year ago, have argued [this for] one of these texts in particular, The Late War, which we will talk a little bit more in a minute. “Joseph [Smith] most likely grew up reading a school book called The Late War by Gilbert Hunt, and it heavily influenced his writing of the Book of Mormon” [Chris and Duane Johnson, “A Comparison of the Book of Mormon and the Late War Between the United States and Great Britain,” January 11, 2014].

The idea that the first readers of the Book of Mormon may have been conditioned to accept its authenticity by political texts written in Biblical style does not really present any particular challenge to the authenticity of the Book of Mormon in my view, nor does the idea that Joseph Smith, the translator of the Book of Mormon, may have been influenced by Biblical language present much controversy.

These are, however, historical assertions, and not proven facts. Before we examine these two interesting propositions, it is important to take notice of significant distinctions between the Book of Mormon and these so called pseudo-biblical texts.

First, it is worth noting that the texts in question are essentially all secular rather than religious in nature. As Shalev notes, “Surprisingly, this was not a predominantly religious idiom” in these particular texts, “as Providence was notably absent from those texts as an active agent” [Eric Shalev, American Zion: The Old Testament as a Political Text from the Revolution to the Civil War (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 85]. “Indeed, God is virtually absent from Snowden’s history [of the American Revolution], a curious fact if only because many other contemporary American historians that wrote about the American Revolution–who were not committed to the Biblical Style–could assign Providence a more significant role than Snowden did [Shalev, American Zion, 95]. So, these writings that had Biblical style tended to be secular, even though people were not afraid to write about God’s influence in the American Revolution in the histories they wrote. Interestingly enough, these particular political texts were non-religious, so that is an important point.

A second point that Shalev notes on this is that you cannot say the Book of Mormon is secular. It’s about as religious as you can get. “… Providence, unlike in those pseudo-biblical pieces in which men were the main, if not sole, historical agents, was omnipresent in The Book of Mormon. Like other contemporary visionary tracts–none of which made use of the Bible’s language–the Book of Mormon proclaimed itself a revelatory text intended to tell authentic religious truths, an attempt that even the most ambitious texts written in pseudo-biblical style would not make” [Shalev, American Zion, 106].

These are two important distinctions–the secular nature of these sources that are supposed to influence readers of the Book of Mormon, and perhaps the text of the Book of Mormon, and also the fact that the Book of Mormon is a religious text.

An additional point that Shalev makes is the orientation or what particular parts of the Bible these texts used. It tended to be the Old Testament. “This strong predilection for the Old rather than the New Testament is evident when one surveys pseudo-biblical texts, a sizeable corpus written during more than a century….

“While each of those texts echoes and resonates with Old Testament narratives and protagonists,” particularly the Book of Chronicles and the Book of Judges “it is hard to find even a single reference to Christ, not to mention other New Testament characters or episodes” [Shalev, American Zion, 101].

An additional point to make is not only did these texts tend to be secular, not talk about God or His influence on history, but they also were focused solely on using language from the Old Testament rather than the New.

The Book of Mormon, although it also focuses on a lot in the Old Testament, is extremely Christo-centric in the way in talks about people and their teachings, and there is New Testament language as much as Old Testament language.

I raise these two mainly as questions posed to Shalev’s thesis, that these texts were influential for readers of the Book of Mormon, or, they somehow may have influenced the text of the Book of Mormon.

Even Shalev admits “…accessing the assertion that pseudo-biblicism had actually participated in and contributed to the reception of the Book of Mormon is a daunting, not to saya futile task.

“As reasonable as such a hypothesis may be, the evidence is mostly circumstantial: We have few…direct references to the pseudo-biblical language by contemporary consumers of those texts, and no direct ties connecting the Book of Mormon to pseudo-biblicism” [Shalev, American Zion, 115].

As far as we can tell, the only place that we can find such evidence, or at least that I have been able to determine, for any connection with somebody who knew something about The Book of Mormon and these political texts that we are talking about are in the writings of anti-Mormon writers, not Latter-Day Saints.

I will give you an example: Abner Kol, who wrote under the pseudonym of Obadiah Dogberry, published a tabloid in Palmyra, known as The Palmyra Reflector. There was a similar tabloid published in Rochester called Paul Pry’s Weekly Bulletin. Here is a sample of this literary master piece. This was published in 1829, about eight months before the Book of Mormon was published. “Now the rest of the deeds of Israel the ‘darkey paramour’ how he yet liveth in shame, and of Joseph and Wanton how they still cleave unto Israel, and of Horace the publican ‘how he couldn’t git no beef’ on the fourth day of the week, and of Hiram the Jeromite, how he gave unto Israel a writing promising to cleave unto him, and how he too done the unclean thing against the body of a large oak, near the precincts of the tabernacle, and of Chad the money lender how he squanders the monies of the children of Samuel the miser. Behold all these things, yea many more, are graven on the massy leaves of the Golden Book, and are now in the custody of Joseph the prophet” (Paul Pry’s Weekly Bulletin, Rochester, New York, August 8, 1829).

Now the person who wrote this hadn’t seen the text of the Book of Mormon, because it hadn’t been published yet, but this perhaps gives some idea of the kind of language they thought they might find in the Book of Mormon.

This is, obviously, a form of pseudo-biblicism that’s adapted locally to events in Palmyra, individuals in Palmyra, whom we can’t fully identify–maybe that is a good thing for history– but although it’s a parody, it also reflects to some degree what critics expected to be published in the Book of Mormon, but such examples, apparently the only examples again come from critics and they tend to be fairly literate critics, who rejected the Book of Mormon, rather than those who received it.

I think it presents another possible challenge to Shalev’s thesis. He argues that the prevalence of writings in the Biblical style made the Book of Mormon more palatable to those who read it, but the evidence leads us to wonder if the reverse was true, and perhaps in terms of reception, it may have been a factor for those who rejected the book. But it is unclear what, if any, impact the genre may have had on those who accepted it.

I’m going to turn it back to Paul here and he is going to talk a little bit more about some of our findings.

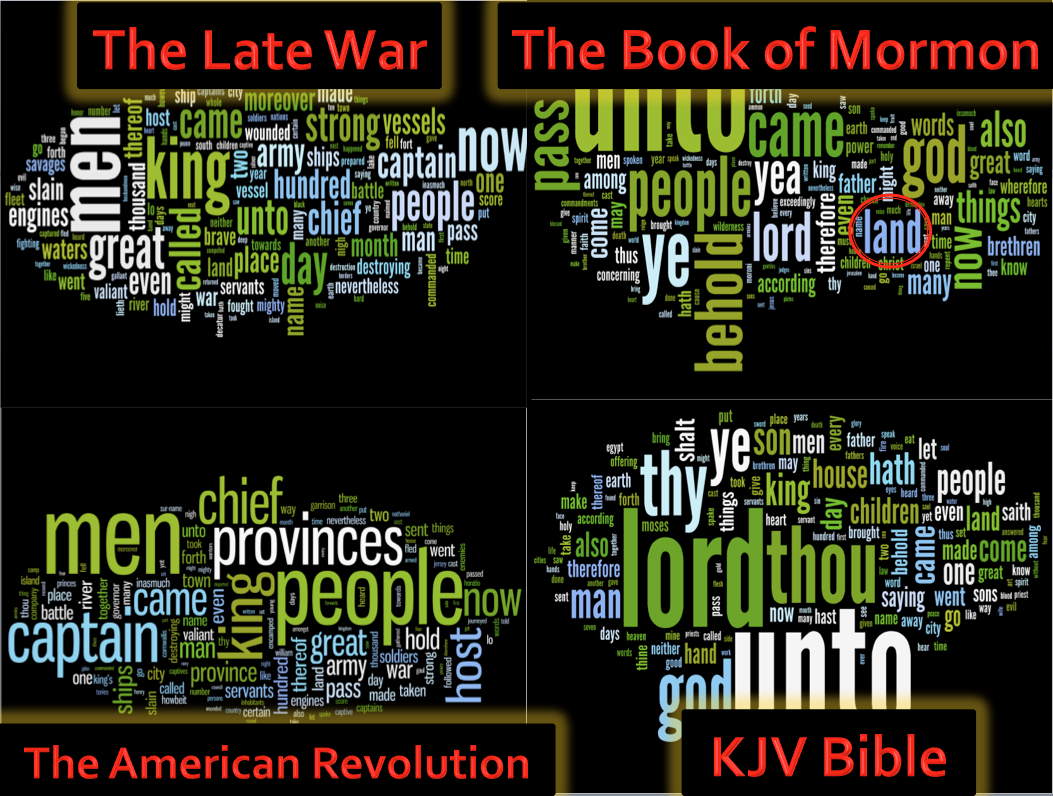

Thank you. Here are some word clouds. There are four word clouds. The size of the word represents the frequency of the use of that word inside a document. There are four documents represented, the Bible, the Book of Mormon, The American Revolution, and The Late War.

Just take a look at those words. Can you identify which book would be associated with which cloud?

Now let me show you which ones are which. The Book of Mormon is in the upper right hand corner, while the Bible is down in the lower right hand corner, The Late War in the upper left hand corner, and The American Revolution down below.

Look how distinctively different the vocabulary is: “unto” is the most prominent word in the Book of Mormon; “the Lord” is the most prominent word in the Bible; The Late War, “men” and “king”; in The American Revolution, “men”, “people” and “captain”.

I want you to take particular note in the size of the word “land” inside the Book of Mormon and its absence in the cloud in those other three documents.

Examining what could be described as the King James Version of the Bible style, the King James style of writing, we look at four dimensions. The first is non-contextual words. These are structural words, they carry no content meaning but they are the words that provide the structure that an author uses to convey his or her message. These are words like “the”, “and”, “but”, and so forth.

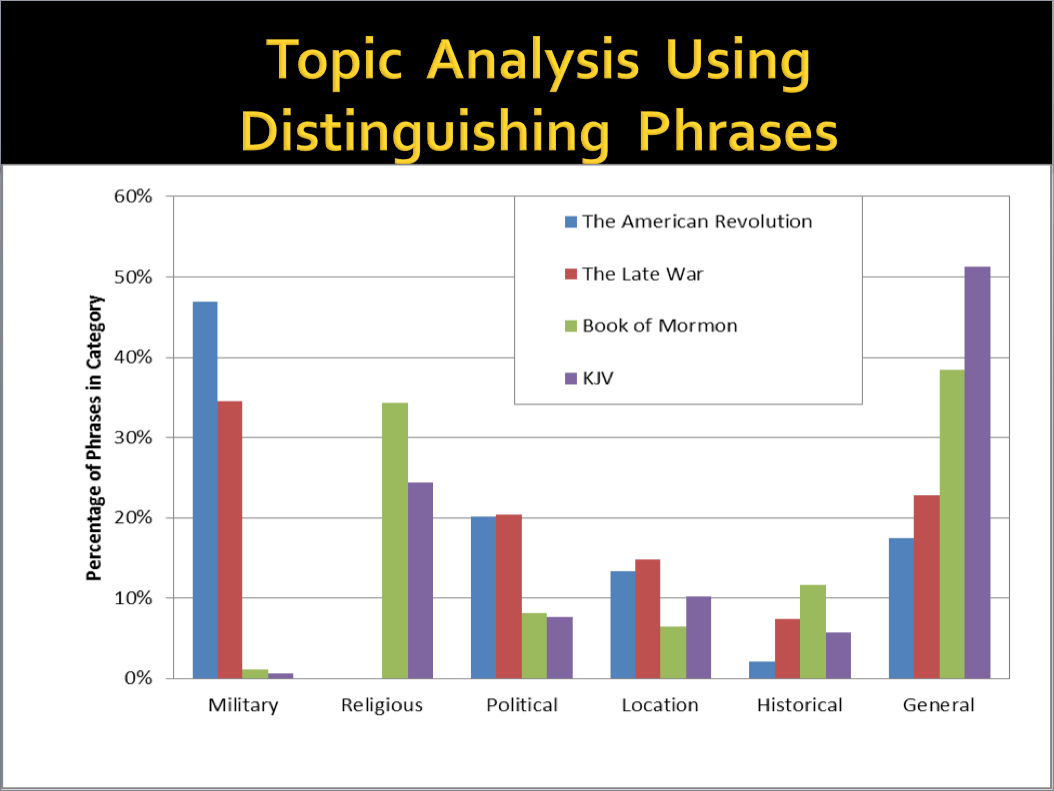

The second is archaic words like “thee” and “thou” and “ye”, a second dimension in describing the King James style. A third is distinguishing phrases. In fact the most predominant in describing that style is “of the Lord.” And last of all, the fourth dimension is the content topics: religion, war, and so on.

Looking at that first dimension of non-contextual words comparing the Book of Mormon to the King James style, and each of those other texts, through the King James style, we find that the similarity is much stronger between the Book of Mormon and the King James style than for the other two documents. In fact the Book of Mormon is about twice as similar as those other two documents in its use of non-contextual words, the structural words, of how the message is put together.

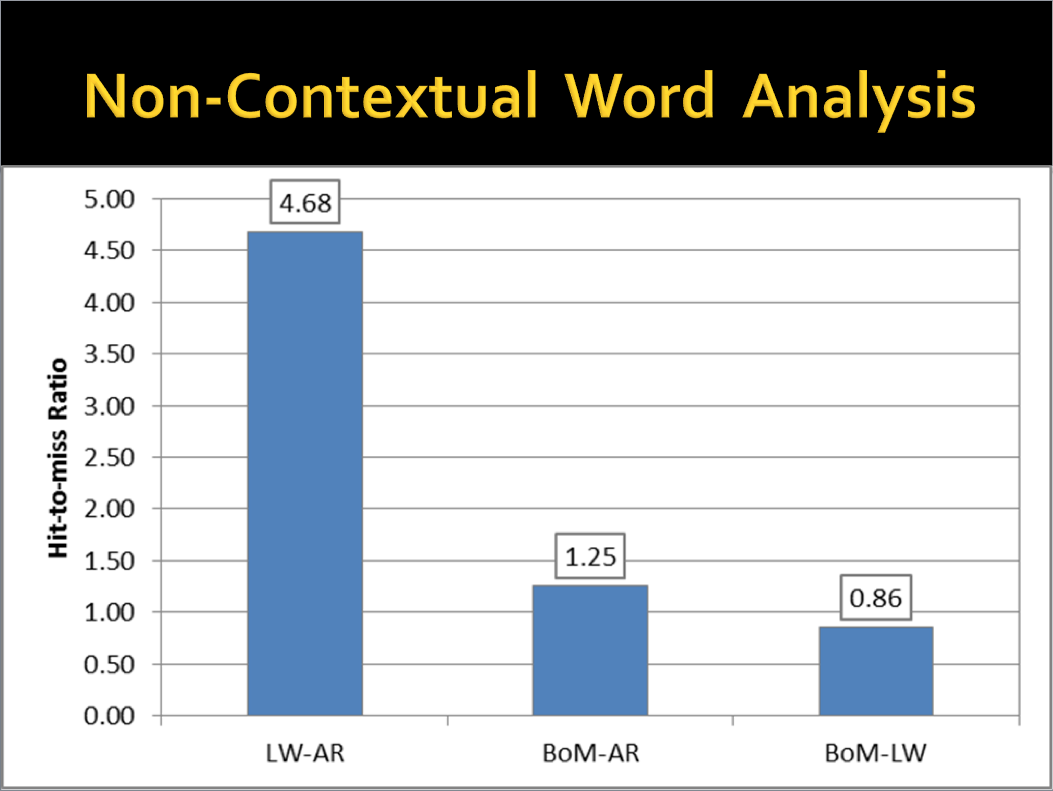

Now looking at it further, comparing The Late War, on the column on the left hand side, to the The American Revolution , and the Book of Mormon compared to The American Revolution and The Late War, we can see that the use of non-contextual words is the about same for the Book of Mormon and The American Revolution and The Late War, but the similarity between The Late War and The American Revolution is about five times stronger, much more internally structured in the use of language in those two documents.

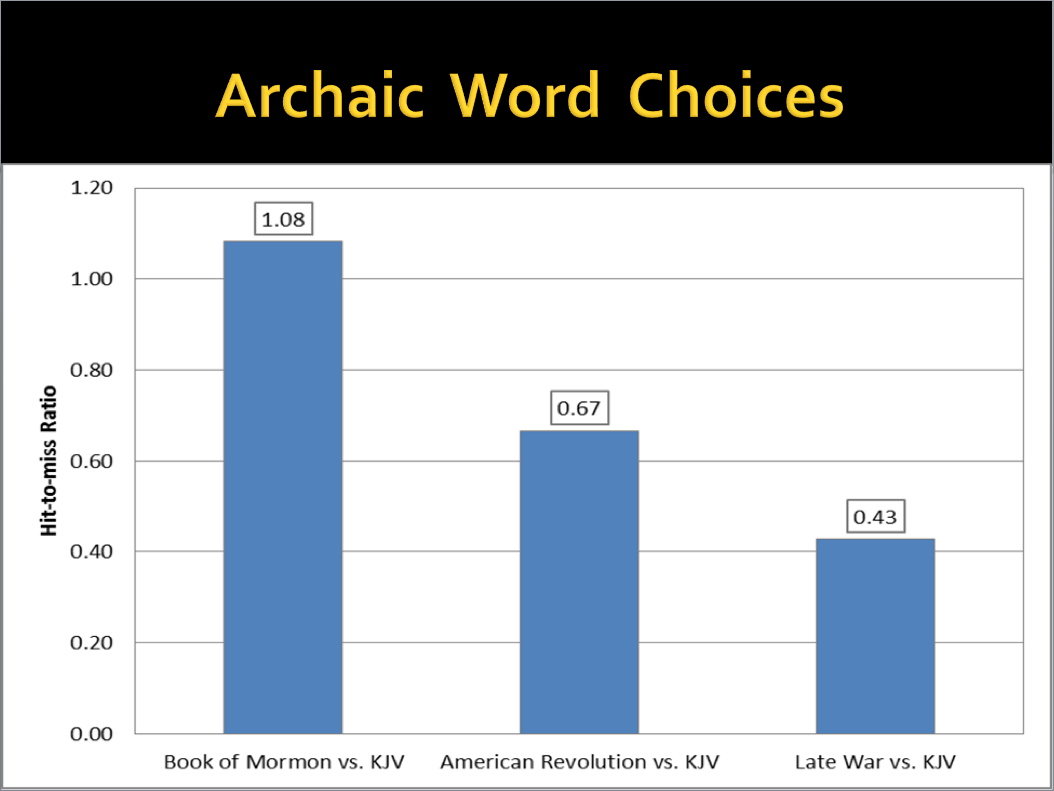

Archaic words such as “thee” and “thou”, for example, the Book of Mormon and the King James version are almost identical in the use of those words while The American Revolution and The Late War use those words much less, with much less frequency.

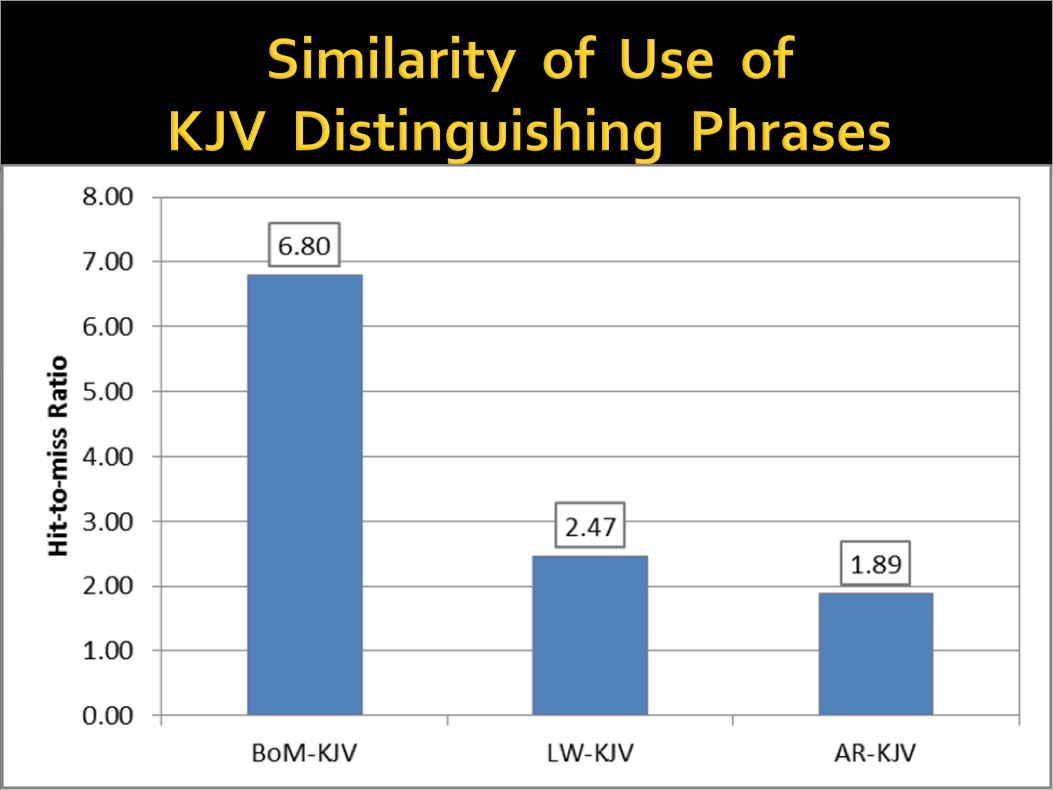

Looking at distinguishing phrases and the similarity of the use of those, comparing on the left hand side the Book of Mormon with the King James Version, about seven times more similar in how they are used than in the other documents: The Late War and The American Revolution. They only get it right about twice while the Book of Mormon gets it right about seven times more frequently.

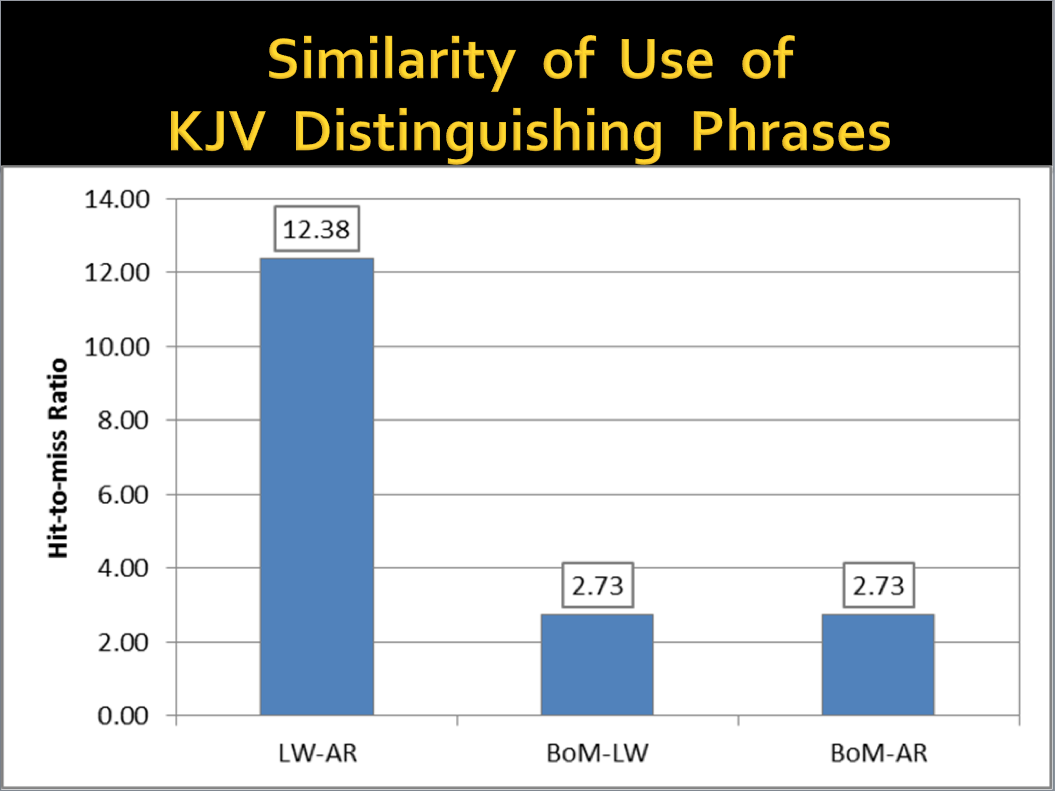

Again, comparing The American Revolution and The Late War, and the similarity of the use of the King James style frequency phrases, The Late War and The American Revolution are over 12 times more similar to each other than the other documents. The Book of Mormon compared to The Late War and The American Revolution much less, on the right hand side.

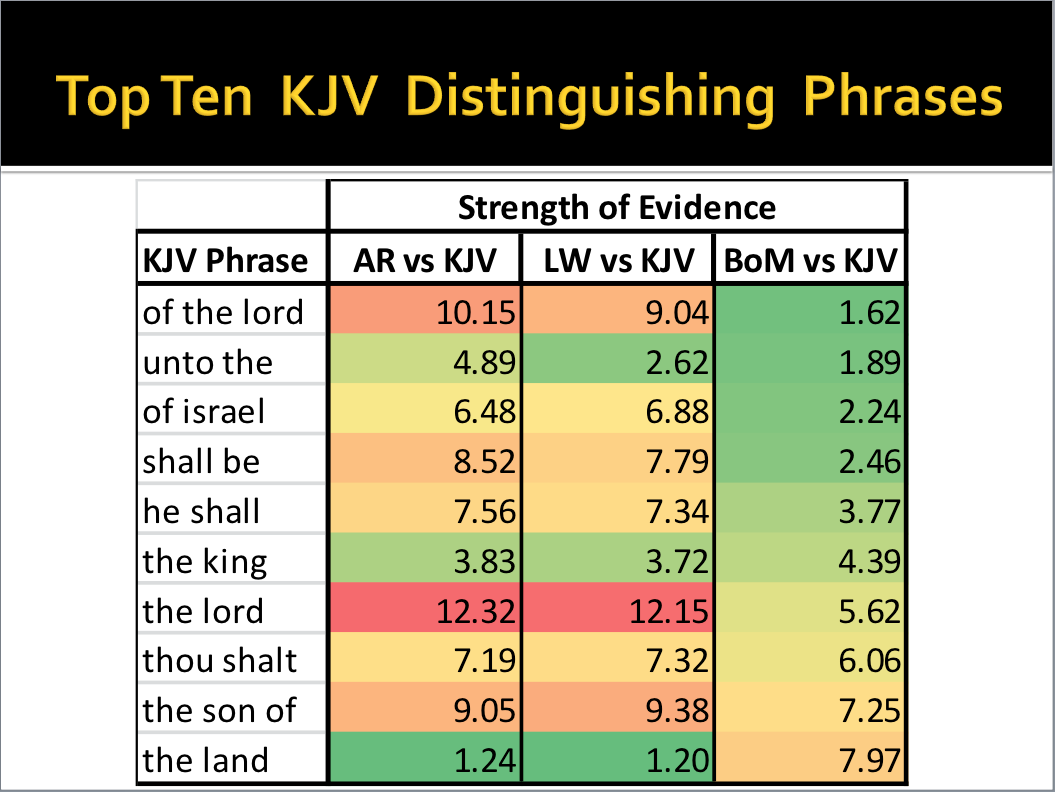

The top ten distinguishing phrases, by the way, “of the Lord”, “unto”, ‘of Israel”, “shall be”, these are the top ten phrases that are distinctively useful in identifying the King James style,

Looking by a color code, the similarity, in the use of phrases, green indicates that the frequency of use between two documents is very much the same; so, for example, the Book of Mormon and the King James version of the Bible on the right hand side, upper right hand corner are very close to being very similar in their use of the phrase “of the Lord”, but the distinctive phrase between the Book of Mormon and the Bible, lower right hand corner, higher number, almost eight, you can see the phrase is “the land”; but if we are comparing The American Revolution to the Bible we see that the use of “the land” is very similar, and the same for The Late War, but the distinction is, the difference in the use of the phrase “the Lord” in The American Revolution and The Late War.

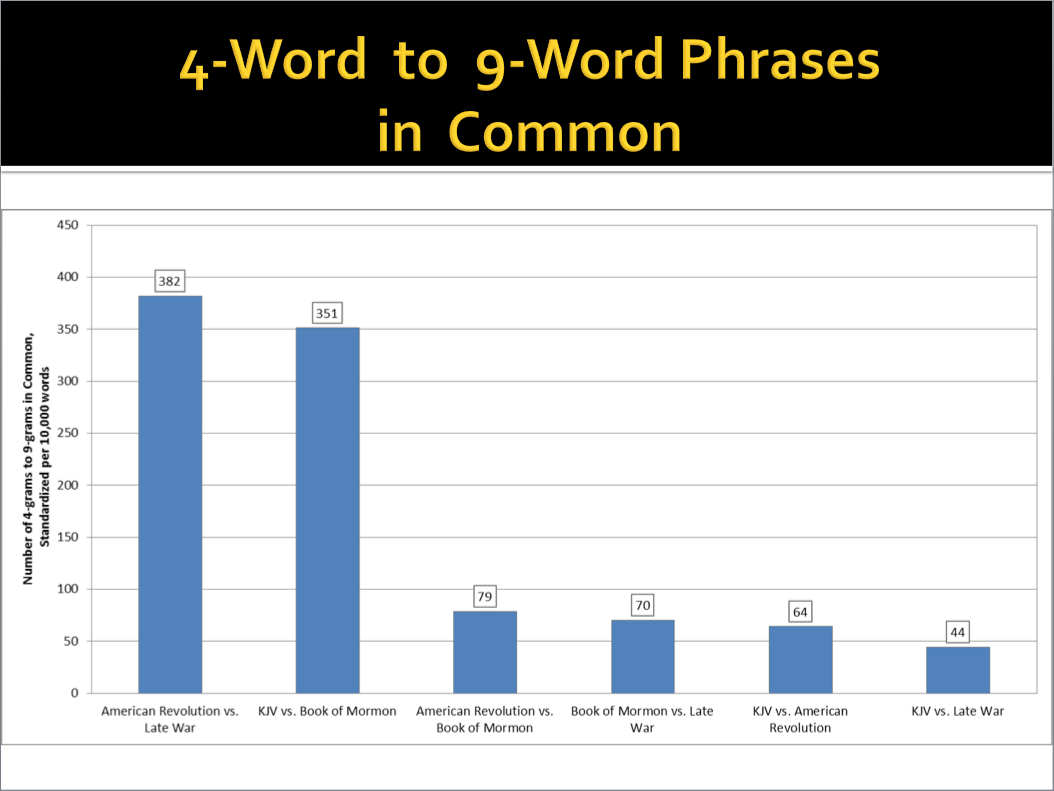

We look at combinations of words, words that form a phrase of four words in length, five, six, seven, up to nine words in length, and see how common those words are used between documents, we see that out of 10,000 word frequencies The American Revolution and The Late War used those common phrases far more frequently–the bars on the left hand side of the graph–as compared to the Book of Mormon.

The imitation of the King James Version by The American Revolution and The Late War appears to be quite an exaggeration in the use of the vocabulary. Words such as “thee” and” thou”, “showeth”, “cometh”, etc.; and exaggerated imagery referring to Great Britain as a “fierce lion, when he putteth his paw upon the innocent lamb [America] to devour him.”

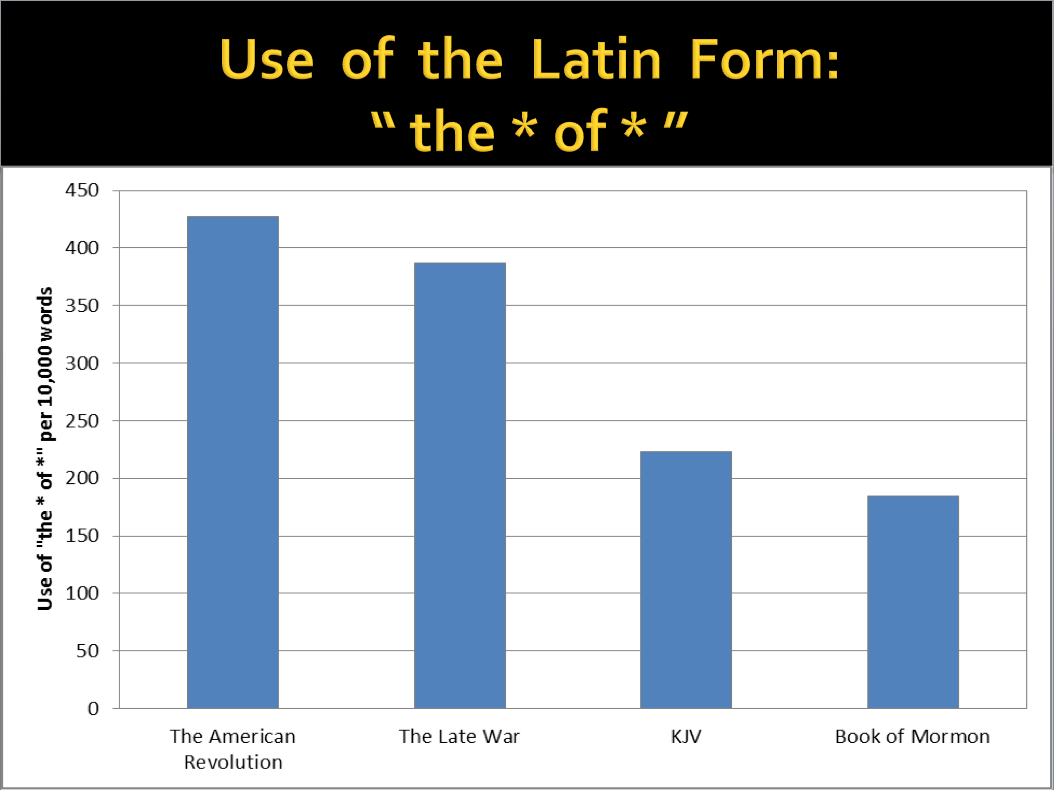

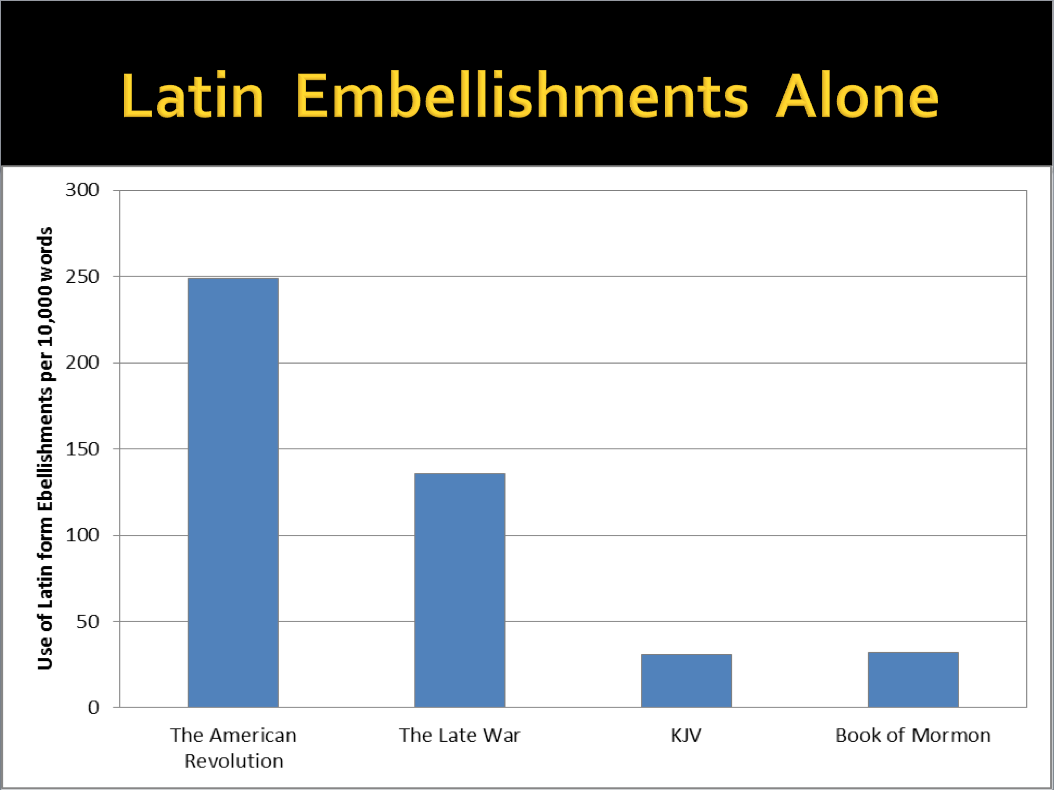

There is also the use of the Latin form “the (some word) of (some word)” forward sequence with “the (something) of (something)” as a possessive; for example “the hand of the king” instead of saying “the king’s hand”; or embellishments: “the engines of destruction” instead of saying “cannons”; or, “the year of the Great Founder of the Christian sect” instead of saying “A.D.” The American Revolution and The Late War use these profusely. For example, on the left hand side, all of these forms per 10,000 words The American Revolution uses over 400 times, The Late War almost 400 times, while the King James Bible and The Book of Mormon are at least half, or less than that amount.

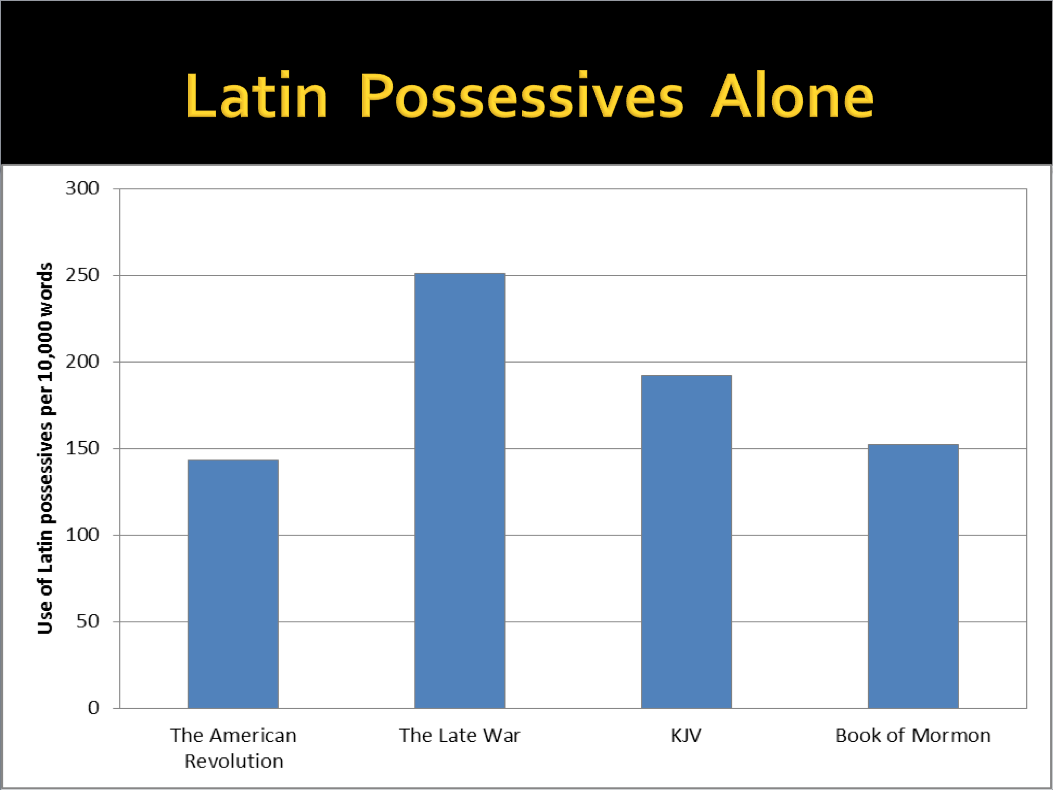

The Latin possessives alone are the most distinguishing for The Late War, but, in comparison again to The Book of Mormon, it’s only about half as frequent.

The Latin embellishments in The American Revolution are used 250 times per 10000, while he Book of Mormon uses it only 25 times or about only 1/10 of that amount.

Looking at topics, The American Revolution is the blue bar, and the red bar is The Late War and we can see that the frequency of the use of topics is very strongly military. And on the topic of religion, not surprisingly, the Book of Mormon, the green bar, and the KJV, the purple bar, are very high whereas, The American Revolution and The Late War are almost zero. So, we see a very distinctive difference in the frequency of the reference of these topics using phrases which are distinctive to each of those texts.

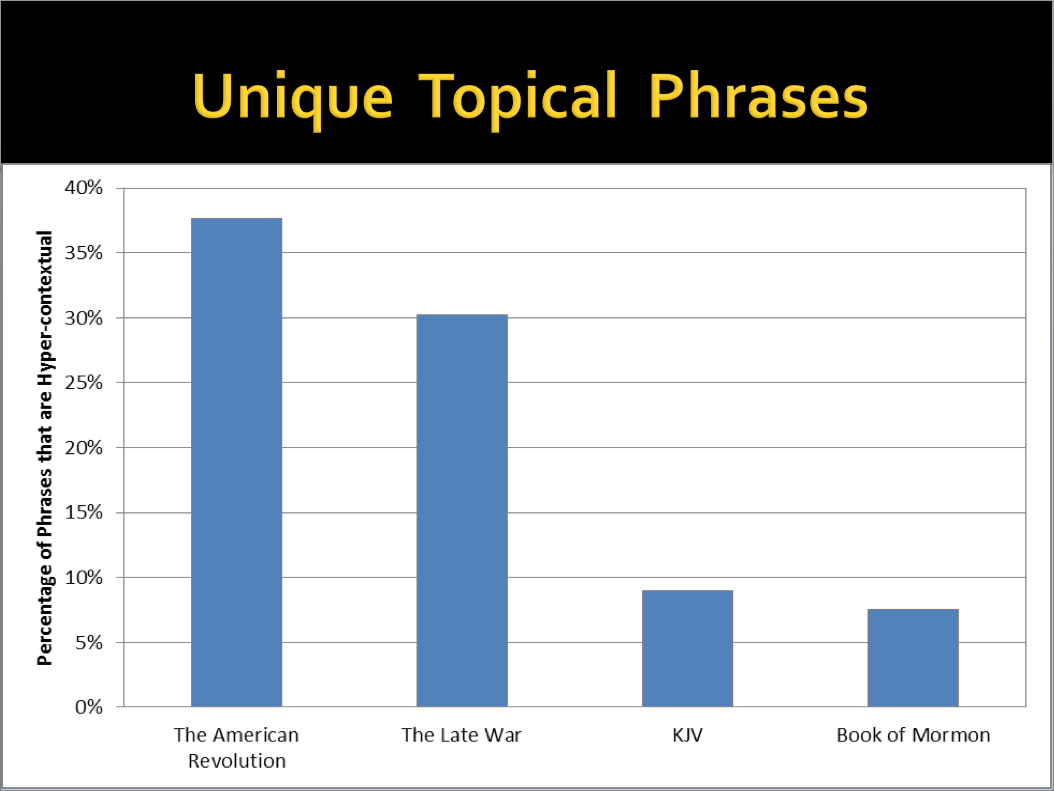

The most unique topical phrases in The American Revolution, over one third of the phrases used in that text as opposed to The Book of Mormon on the far right hand side, which is only about six or seven percent of the time, 1/20 of the amount. Their distinctive use of phrases is repeated in The American Revolution and The Late War, as opposed to in the Book of Mormon. There are a number of superficial similarities in the topics, of course, when you are talking about war and political systems.

It’s also been pointed out that there is an order of events that is going on that seems to be similar. They talk about a battle at a fort, a rather superficial similarity, because if you are having a battle, how often is it at a fort, or the taking of a key city? Or having heroes? Of course if the narrative is on the topic of war those are references that are going to be identified very frequently, but they say that there is also this order first a battle at a fort, and then there is the taking of a city, and as a result we have heroes. But what we find is that the most interesting thing in examining these texts is the contorted tortuous way that it comes about finding those similarities because the order of events sometimes is separated by long periods of time, or they come in reverse order, so those similarities do not stand up to comparison. But whenever you have books that have the same topic or the same genre there will always be similarities. That has nothing to do with the source of the authorship or plagiarism, let alone influence, because similar words are always going to be there when you have similar topics.

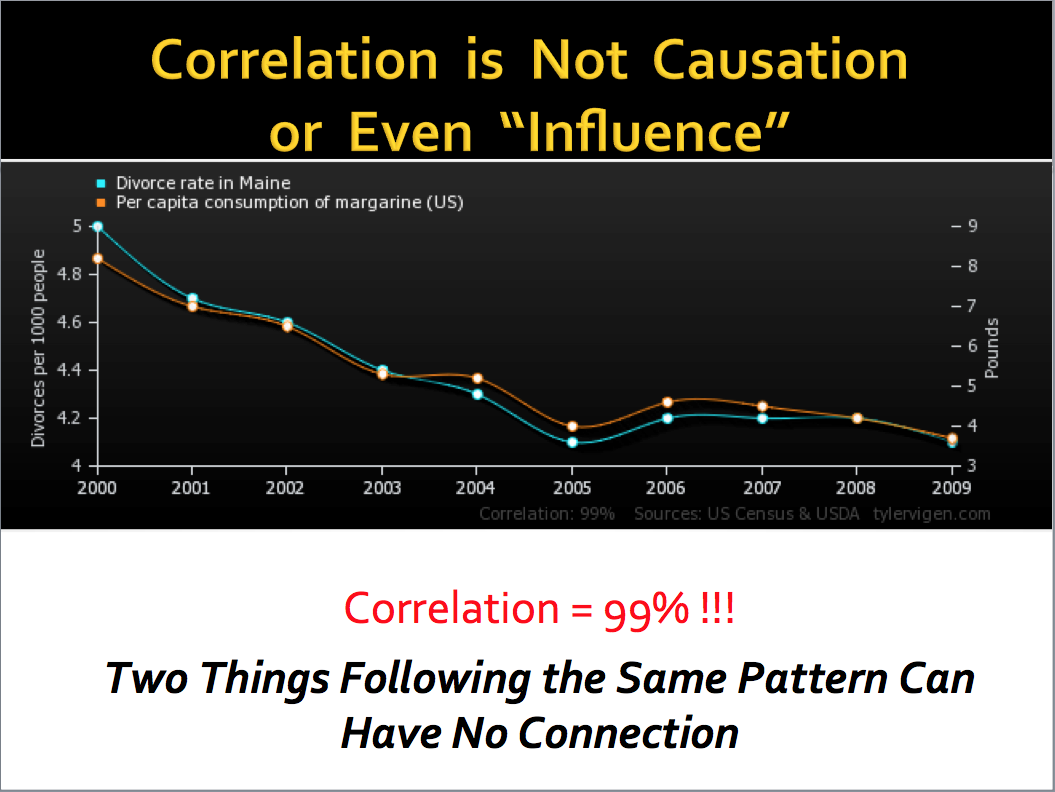

Take a look at this graph if you would for a moment. This shows over time in the blue line the divorce rate in the State of Maine. It also shows on the orange line the per capita consumption of margarine in the United States. The correlation between those two patterns is amazingly high at 99% out of a possible 100%, and so causation and correlation are much different than each other and two things can follow almost exactly the same pattern and have no connection whatsoever. Even if you are looking at all books in the world, or even if you are limiting yourself to 200,000 books in the world, this is what we call a Big Data Search, one must be aware of the Big Data Fallacy, because in any comparison there is always going to be something that is the “closest” to something else and closest doesn’t mean close. But if you have a large enough group, the “closest” one can appear to be, just in relative speaking terms, the “close” one, and this gives the false impression of two things being the same, or of the same origin. If that is what a researcher is looking for there is an easy trap to fall into of saying: “I have found it” when, in fact, there is nothing there at all.

There is also the “China” Fallacy. Think about this for a moment. If you consider yourself as being a one in a million guy on some characteristic, then there are a 1000 people in China who are just like you, just because the comparison group is so huge. If you search far enough and wide enough you’re always going to find something that is “similar”.

We conclude then, on these four dimensions of the King James style: non-contextual words; archaic words, structure of the language, the unusual words that are used; distinguishing phrases; and the content topic–the Book of Mormon is more similar to the King James style than either The American Revolution or The Late War. In fact The American Revolution and The Late War are similar to the King James style only in a contorted pseudo-biblical exaggerated caricaturation of the two. So, if Joseph Smith was “influenced” by those books, his imitation of the King James style was better than theirs. Joseph Smith was either a literary genius, or a prophet, and we are all free to take our pick.

Our overall conclusion using appropriate statistical techniques: the Book of Mormon’s four main authors can easily be distinguished between each other. The Book of Mormon is more substantially similar to the King James style in our four dimensions than to either of those two proposed comparisons.

Please join with me in thanking our research contributors: James Lee, Larry Bassist, Emily Watts, Elena Hirst, Jzsanette Cullen.

Q: How was it known that Joseph Smith read The Late War?

A: Well, it is not. It has been assumed by recent critics who proposed it as a source, and they pointed to certain nouns or words that are used and a few other things. One of the arguments that is used by those who want to suggest a connection, is The Late War, if you look at the title page–I do not have a blowup of it here on the screen–one of the things that the author of The Late War was trying to do was he hoped to write this in the Biblical style, to get this into the schools, so that the children would get excited about reading history in the biblical style. In fact, the reverse seemed to be true. It really doesn’t seem to have done that well. So the author expresses the desire to get this into the schools, and proponents of the theory that The Late War influenced the Book of Mormon have taken that as a given established fact, that it got into all these schools, but there is no evidence of that. So that is a good question.

Q: A recent study indicates that the language of the Book of Mormon is mostly 1600’s English. What does that mean?

A: It means exactly what we have presented here today, that the style in the King James Version of the Bible and in the Book of Mormon are very, very similar to each other, and attempts at imitating that by other people have really not done a very good job of imitating it.

Q: Where can one find the latest research articles or books regarding word print studies?

A: By the way, the official name, or technical name, for word print studies is stylometrics, and this is primarily found in the literature of computational linguistics or the digital humanities.

Q: Chris Johnson in his 2013 ex-Mormon Foundation presentation spent 80 minutes explaining how modern computer analysis of texts is increasingly showing how the Book of Mormon is a product of contemporary texts. What do you think of this trend, if anything?

A: There is no such trend, as we were just explaining. That’s all based upon Big Data fallacies and China-Syndrome fallacy.

Q: The Book of Mormon uses the word “in fine.” I am sorry; I cannot read the rest of it. Whoever has this question, I will be happy to talk with you in person.

Q: One of the criticisms of The Late War in the Book of Mormon raised by Ben McGuire in his Interpreter essay said that Johnson’s critics have all “cherry-picked” their comparative texts. How did you settle on the The American Revolution as the only other comparator text? Do you need more to strengthen your conclusions?

A: We had to start somewhere and The Late War was one that they used. There are other texts that we can talk about, but these were among those that they mentioned. Yes, we will be adding texts to our research.

Q: How many authors does your research indicate are in the Book of Mormon?

A: It is easy to distinguish the primary authors and speakers within the Book of Mormon. It is easy to find three. It is easy to find four. By the way, when we do this kind of study, we are not identifying who they are ahead of time and then looking for them, we just look to find if there are consistencies that cluster together that can be identified as the speaker. The most amazing thing, and we have found this now consistently from some studies we have done back in the 1970s, is they cluster together and they cluster together consistently, so it is easy to find three and four and five and six, as well. What happens after that is that the sample sizes start getting smaller and smaller, so it gets hard to distinguish more. But there are as many as 23 speakers in the Book of Mormon. We have an ongoing stream of research on that topic.

Q: What stylometric methods have you used to distinguish between authors?

A: We use multivariate statistics, principally discriminant analysis and principal components analysis. We also use methods that come from the genomic literature, nearest shrunken centroids, and our modification of that model includes the open-set possibility of someone else that a proposed author called “extended nearest shrunken centroids.”

[Editor’s note: This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.]